Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Kleist family.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

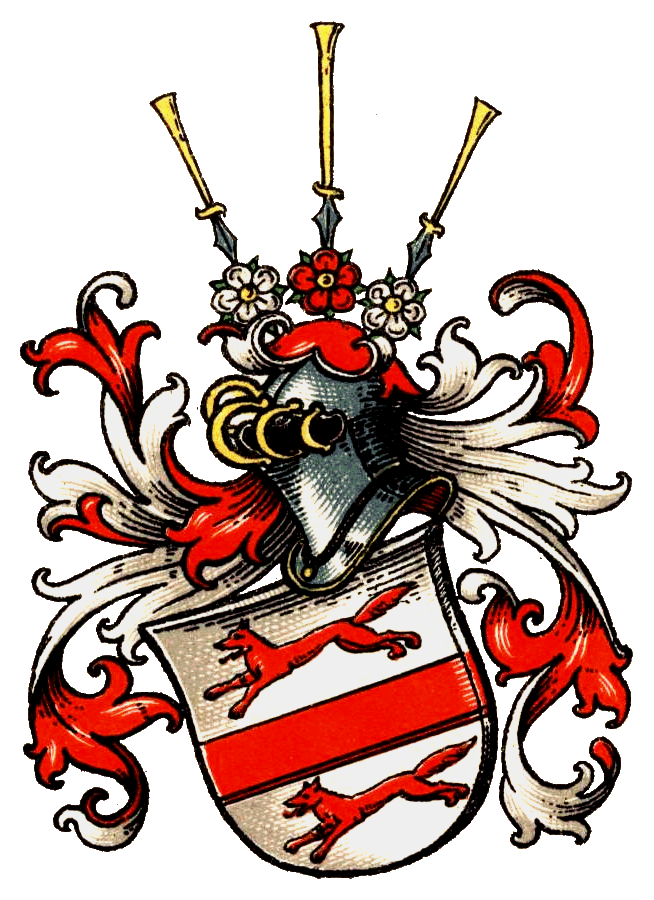

Kleist family

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

The House of Kleist is the name of an old and distinguished Prussian noble family, originating in Pomerania, whose members obtained many important military and administrative positions within the Kingdom of Prussia and later in the German Empire. Members of the family served as officers in Prussian and German conflicts including the War of Spanish Succession, War of the Austrian Succession, Seven Years' War, Napoleonic Wars, World War I and World War II.

The poet and author Heinrich von Kleist is the most famous member of the family.

Notable members

[edit]- Georg Kleist (around 1435–1508); Vogt of Rügenwalde and Chancellor to Bogislaw X, Duke of Pomerania

- Henning Alexander von Kleist (1677–1749); Prussian field marshal during the War of Spanish Succession, War of Austrian Succession and Great Northern War.

- Ewald Jürgen von Kleist (c. 1700–1748); co-inventor of the Leyden jar

- Henning Alexander von Kleist (1707–1784); Prussian lieutenant general

- Ewald Christian von Kleist (1715–1759); German poet and soldier. (Depicted on the Equestrian statue of Frederick the Great)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Gottfried Arnd von Kleist (1724-1767); Prussian major general during the Seven Years' War and leader of Freikorps Kleist; nicknamed the "Green Kleist". Commanded an independent corps that participated in the "Glorius Raid of 1762". (Depicted on the Equestrian statue of Frederick the Great)

- Franz Kasimir von Kleist (1736–1808); Prussian general of the infantry, military governor of Magdeburg

- Barbara Sophia von Kleist; mother of Adam Stanisław Grabowski (1741–1766) Prince-Bishop of Ermland/Bishopric of Warmia

- Marie von Kleist (1761–1831); lady-in-waiting to Queen Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and her close confidant

- Friedrich Emil Ferdinand Heinrich Graf Kleist von Nollendorf (April 9, 1762 – February 17, 1823); Prussian field marshal during the Napoleonic Wars

- Franz Alexander von Kleist (1769–1797); Soldier and poet

- Heinrich von Kleist (October 18, 1777 – November 21, 1811); German poet, dramatist, novelist and short story writer. The Kleist Prize, a prestigious prize for German literature, is named after him

- Karl Wilhelm Heinrich von Kleist (1836–1917); Prussian General of the Cavalry

- Hans Hugo von Kleist-Retzow (1814–1892); Prussian Oberpräsident and conservative politician

- Ruth von Kleist-Retzow (1867–1945); Countess of Zedlitz-Trützschler by birth.

- Alfred von Kleist (1857–1921); German lieutenant general in World War I

- Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist (1881–1954); German field marshal of the Wehrmacht during World War II

- Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin (1890–1945); conspirator in the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler

- Karl Wilhelm von Kleist (1914–1994); German brigadier general of the Bundeswehr

- Ewald-Heinrich von Kleist-Schmenzin (1922–2013); Son of Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin; another conspirator in the 20 July bomb plot and founder of the Munich Security Conference

- Erica von Kleist (1982–); jazz musician

External links

[edit]Kleist family

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia