Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

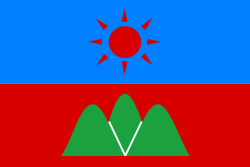

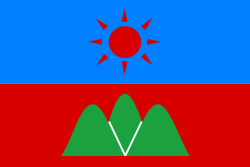

Wa State

View on Wikipedia

Wa State[n 1] is a de facto independent state[5][6][7][8] and self-governing region[14][15] in Myanmar that has its own political system, administrative divisions and army.[5][6][7] While the Wa State government recognises Myanmar's sovereignty over all of its territory,[1][2][3][4] this does not include allegiance to any specific government.[16] The 2008 Constitution of Myanmar officially recognises the northern part of Wa State as the Wa Self-Administered Division of Shan State.[17] It is run as a de facto one-party socialist state ruled by the United Wa State Party (UWSP),[8] which split from the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in 1989. Wa State is divided into three counties, two special districts, and one economic development zone. The administrative capital is Pangkham, formerly known as Pangsang. The name Wa is derived from the Wa ethnic group, who speak an Austroasiatic language.

Key Information

History

[edit]For a long time,[timeframe?] headman tribes were dispersed around the Wa mountainous area, with no unified governance. During the Qing dynasty, the region became separated from the tribal military control of the Dai people. British rule in Burma did not administer the Wa States[18] and the border with China was left undefined.[19]

From the late 1940s, during the Chinese Civil War, remnants of the Chinese National Revolutionary Army retreated to territory within Burma as the communists took over mainland China. Within the mountain region Kuomintang forces of the Eighth Army 237 division and 26th Army 93 division held their position for two decades in preparation for a counterattack towards mainland China. Under pressure from the United Nations, the counterattack was cancelled and the army was recalled to northern Thailand and later back to Taiwan; however, some troops decided to remain within Burma. East of the Salween river, indigenous tribal guerrilla groups exercised control with the support of the Communist Party of Burma.

During the 1960s, the Communist Party of Burma lost its base of operations within central Burma, and with the assistance of the Chinese communists, expanded within the border regions in the northeast. Many intellectual youths from China joined the Communist Party of Burma, and these forces also absorbed many local guerrillas.[20] The Burmese communists gained control over Pangkham, which became their base of operations.

At the end of the 1980s, the ethnic minorities of northeast Burma became politically separated from the Communist Party of Burma. On 17 April 1989, Bao Youxiang's armed forces announced their separation from the Communist Party of Burma, and formed the United Myanmar Ethnicities Party, which later became the United Wa State Party. On 18 May, the United Wa State Army signed a ceasefire agreement with the State Law and Order Restoration Council, which replaced Ne Win's military regime following the 8888 Uprising.[21] After the ceasefire, the Myanmar government began to call the region "Shan State Special Region No. 2 (Wa Region)"[22]: 111–112 (Parauk: Hak Tiex Baux Nong (2) Meung Man;[23] Chinese: 缅甸掸邦第二特区; Burmese: "ဝ" အထူးဒေသ(၂)).

In 1990s, Wa State obtained Southern area by force. From 1999 to 2002, 80,000 former opium farmers from the northern area of Wa State were forcefully resettled into the more fertile south for food production, improving food security and laying the groundwork for a ban on drug production in Wa State. Some groups report that thousands died as a result of resettlement.[24]

Tensions between the central government and Wa State were heightened in 2009.[25] During this time, peace initiative proposals by Wa State were rejected by the Myanmar government.[26] The government warned on 27 April 2010 that the WHP program could push Myanmar and Wa State into further conflict.[27][clarification needed]

In 2012, Wa State began a major road construction program to link all townships with asphalt roads.[22]: 60 By 2014, asphalt roads ran through the northern townships of Wa State and connected the Wa townships of Kunma, Nam Tit, and Mengmao to the Chinese towns of Cangyuan and Ximeng.[22]: 60

After the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état the Wa began to oppose the Myanmar government more directly, shifting away from their strategy of "forward defense" of supporting smaller anti-government forces militarily which was supposed to keep the Tatmadaw from violating ceasefires, with the goal of extending their political and military influence towards Central Myanmar.[28]

When fighting in northern Shan State escalated in late October and early November in 2023, Wa State took a neutral position urging on 1 Nov for a ceasefire. The UWSP has again stated that they would retaliate against any military action against Wa.[29][30]

Tensions between Wa State and Thailand increased in November 2024 over the presence of UWSA bases allegedly encroaching on Thai territory.[31]

Politics, society and law

[edit]

Wa State is divided into northern and southern regions which are separated from one another, with the 13,000 km2 (5,000 sq mi) southern region bordering Thailand and consisting of 200,000 people.[32] The total area of the region controlled by Wa State is approximately 27,000 kilometers.[22]: 4 The political leaders of Wa State are mostly ethnic Wa people.

The working language of the Wa State government is Mandarin Chinese.[33][34][35] Southwest Mandarin and Wa are widely spoken by the population, with the language of education being Standard Chinese. Television broadcasts within Wa State are broadcast in both Mandarin and Wa. Commodities within Wa State are brought over from China, and the renminbi is commonly used for exchanges. China Mobile has cellular coverage over some parts of Wa State.[32]

Government

[edit]The Wa State government emulates many political features of the government of the People's Republic of China, having a central party known as the United Wa State Party, which also has a Central Committee and a Politburo. Wa State also has a Wa People's Congress and a Wa People's Political Consultative Conference, respectively mimicking the National People's Congress and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. Before the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état, whilst Wa State was highly autonomous from the control of the central government in Naypyidaw,[36][37] their relationship was based on peaceful coexistence and Wa State recognised the sovereignty of the central government over all of Myanmar.[32]

Legal system

[edit]The legal system in Wa State is based on the civil law system, with reference to the laws of China. As of at least 2015, Wa State imposes the death penalty (which is abolished at the national level in Myanmar) for armed assault, rape, murder, and child abuse.[22]: 53 After being sentenced to death, prisoners are sent directly to the execution ground.[38]

Labour camps exist in Wa State and relatives of those who are imprisoned or conscripted are often taken hostage by the state. The state is governed by a network of Maoist insurgents, traditional leaders such as headmen, businessmen, and traders, without democratic elections or the rule of law.[39]

Most people do not have Chinese or Myanmar ID cards, but Wa State ID cards are often recognised in those countries. It is easy for citizens to enter them if they avoid the official border crossings.[39]

Demographics

[edit]The most-practiced religion, outnumbering Islam, Buddhism and folk religions, is Christianity, even though there are frequent crackdowns on it conducted by the Maoist government. An example for this is a campaign against churches built after 1992 in September 2018.[40][41][42]

There used to be up to 100,000 Chinese nationals residing in Wa State, many of them engaging in business. In 2021, the Chinese government ordered them to return to their homeland to combat online fraud allegedly committed by many of them.[43] The Chinese exodus has had a negative impact on the Wa economy.[44]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Wa State is divided into counties (Parauk: kaung:; Chinese: 县), special districts (Parauk: lum; Chinese: 特区), an economic development zone and an administrative affairs committee. Each county is further divided into districts (Parauk: veng; Chinese: 区).

Below these are township-level administrations: townships (Parauk: ndaex eeng / yaong:; Chinese: 乡) and streets (Parauk: laih; Chinese: 街).

| Level | County-level | District-level | Township | Village |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division Type |

Special District (lum / 特区) | Street (laih / 街) Town (ceung / 镇) Township (daux eeng: / 乡) |

Group (组) Village (yaong: / 村) | |

| Economic Development Zone (经济开发区) | ||||

| County (kaung: / 县) | Avenue (daux laih / 街道) District (veng / ဝဵင်း / 区) | |||

| Administrative Affairs Committee (行政事务管理委员会) |

Township (southern) (yaong: / 乡) | |||

In the table above, names in apostrophes are in Wa/Dai/Mandarin order. Avenue (daux laih / 街道) is found only once in Mong Maoe County; town (镇 / "ceung") is found only once in Mong Phing EDZ. Avenues and streets are metaphorical urban-type division name analogical to subdistricts of China and should not be understood literally. They are further subdivided into groups. Villages are rural counterparts of groups and are below townships. In southern Wa, townships are given the township identity (乡) according to their Mandarin name yet not subdivided into villages with their Wa names indicate they are natural settlements (yaong: / 寨), but might be a part of compound like daux eeng yaong: XX (XX-settlement township / XX寨乡).

In general, the Wa names of divisions follow the Romance naming order. For example, Veng Yaong Leen means Yaong Leen District and is a veng (district) instead of a yaong: (natural settlement). That of the town of Mong Phing in Mong Phing EDZ is an exception – it follows the Germanic naming order as "Mong Phing Ceung" instead of "Ceung Mong Phing". In the Wa language, x at the end of a syllable represents a glottal stop.

In the sections below, names in bold indicate county seats. Names with "quotation marks" are pinyin transcriptions of Mandarin while names in italics are Burmese transcriptions of Mandarin. Although Mandarin is one of the four working languages of Wa State, some Mandarin administrative names are non-canonical. For example, 班阳区 and 邦洋区 are two different transcriptions of the same official Wa or Dai name of Pang Yang District.

Northern area

[edit]Wa State's northern area is divided into three counties, two special districts, and one economic development zone. Each county is further divided into districts; there are 21 districts in total.

northern Wa State

County

- Counties

- Hopang Township (kaung: Ho Pang, 富邦县):

- 1. Ho Pang District (veng Ho Pang, 富邦区)

- 2. Pang Long District (veng Pang Long, 邦隆区)

- 3. Nang Teung District (veng Nang Teung, 南邓区)

- 4. Nawi District (veng Nax Vi, 纳威区)

- Mongmao County (kaung: Meung Mau, 勐冒县):

- 5. Kaung Ming Sang District (veng Moeknu, 公明山区) and Monghmau Avenue (daux laih Meung Mhau, 新地方街, county seat)

- 6. Panwai District (veng Pang Vai, 邦外区 (班歪区))

- 7. Taoh Mie District (veng Taoh Mie, 栋玛区 (昆马区))

- 8. Yaung Lin District (veng Yaong: Leen, 永冷区)

- 9. Long Tan District (veng Nhawngngit, 龙潭区)

- 10. Ai Chun District (veng Cheung: Miang, 岩城区)

- 11. Yingpan District (veng Kawnmau, 营盘区)

- 12. Man Ton District (veng Man Ton:, 曼东区)

- 13. Ling Haw District (veng Moek Raix, 联合区)

- 14. Klawngpa District (veng Klawng: Pa, 格龙坝区)

- Monglin County (kaung: Mang' Leen', 勐能县):

- 15. Man Shiang District (veng Man Shiang, 曼相区)

- 16. Nong Kied District (veng Nong: Kied, 弄切区)

- 17. Paleen District (veng Pa Leen (Nang Khang: Vu), 南抗伍区)

- 18. Nakao District (veng Nax Kao, 纳高区)

- 19. Pang Yang District (veng Pang Yang, 邦洋区)

- Mong Pawk County (kaung: Meung' Bawg, 勐波县):

- 20. Nam Phat District (veng Nam Phat, 南排区)

- 21. Mong Pawk District (veng Meung' Bawg, 勐波区, county seat)

- 22. Mong Ning District (veng Meung' Ning, 勐念区)

- 23. Mong Ka District (veng Meung' Ka, 勐嘎区)

- 24. Hotao District (veng Hox Tao, 贺岛区)

- 25. Meng Phing Economic Development Zone (veng Meung Phien, 勐平经济开发区)

- Special districts

- Pangkham Special District (lum Pang Kham, 邦康特区):

- Guanghong Township (daux eeng: Kwang: Hong:, 广洪乡)

- Na Lawt Township (daux eeng: Na Lawt, 那洛乡)

- Man Phat Township (daux eeng: Mam Phat, 南帕乡)

- Tawng Aw Township (daux eeng: Tawng Aw, 等俄乡)

- Yaong Ting Township (daux eeng: Yaong Ting, 永定乡)

- Man Mao Township (daux eeng: Man Mao, 芒冒乡)

- Mong Phing Economic Development Zone (Meung' Phing, 勐平经济开发区):

- Mong Phing Town (ceung Meung' Phing, 勐平镇, seat)

- Mong Phing Prim Township (daux eeng: Mong Phing Prim)

- Tong Long Township (daux eeng: Tong Long)

- Yaong Khrawm Township (daux eeng: Yaong Khrawm, 团结乡)

- Pang Sax Cax Township (daux eeng: Pang Sax Cax)

- Kawx Sawng Township (daux eeng: Kawx Sawng)

Wa State overlaps with seven de jure townships designated by the Burmese government. The geographic relationship between districts (second level) and special districts (first level) of Wa State and districts of Shan State are listed below:

- Kho Pang Township of Shan State

- Cheung Miang District (Ai Chun)

- Nawi District

- Mongmao Township of Shan State

- Kaung Ming Sang District

- Klawngpa District

- Pangwaun Township of Shan State

- Kunma District

- Wangleng District (Yaong Leen)

- Man Phang Township of Shan State

- Ling Haw District

- Namphan Township of Shan State

- Kawnmau District (Yingpan)

- Pang Yang Township of Shan State

- Pang Yang District

- Ting Aw District

- Weng Kao District (Daux Kaung Township?)

- Pangkham Special District

- Mong Yang Township of Shan State

- Mong Pawk District

- Mong Ngen District (Mong Ning?)

- Hotao District

On 15 January 2024, Hopang and Pan Lon are officially transferred to Wa State by Myanmar's government.[11][45]

Southern area

[edit]Wa State's southern area is administered by the Fourth Theater Command as the "171st military region" and enjoys a high degree of local autonomy. For example, the UWSP allowed it to implement its own COVID-19 policies.[46] The region is not part of traditional Wa territory, but was granted in 1989 by the then-ruling Burmese military junta for the UWSA's cooperation in their efforts against drug warlord Khun Sa.[47] These territories were originally inhabited by the Austroasiatic Tai Loi peoples, but now include significant Lahu and Shan communities, as well as Wa settlers.

The Southern area is administrated by the Southern Administrative Affairs Committee (Parauk: Meung Vax Plak Caw, Chinese: 南部行政事务管理委员会). The area can further divided into several districts:

- Wan Hoong District (veng Gawng Sam Song:, 万宏区, area seat)

- Hui Aw District (veng Huix Awx, 回俄区)

- Yaong Khrao District (veng Yaong Khraox (Yaong Gawng), 开龙区)

- Yaong Pang District (veng Yaong Pang, 永邦区)

- Meung Cawd District (veng Meung Cawd, 勐角区)

- Yaong Moeg District (veng Yaong: Moeg (Num Moeg), 勐岗区)

- Kha Na District (veng Khax Nax, 户约区)

Kha Na District seems to have been merged into Wan Hoong District.

Treatment of original inhabitants

[edit]In recent years tens of thousands of people (according to the Lahu National Development Organization claims 125,933 from 1999 to 2001 alone) have resettled from northern Wa State and central Shan State to the southern area, often due to pressure by the Wa government. These actions were intended to strengthen the Wa government's position there, especially the Mong Yawn valley which is surrounded by mountains on all sides is a strategically important location.[24] Wa people were also relocated from villages on mountain peaks to the surrounding valleys, officially to offer the residents an alternative to the cultivation of opium. After the resettlement, the Wa government allowed ethnic Wa settlers to grow opium for three more years and sell it freely. Serious human rights violations were reported during the resettlement and many people have died, around 10,000 alone during the rains of 2000 since the Wa settlers were not accustomed to tropical diseases like malaria in the warmer southern area.[48][24]

The original inhabitants of the area have been discriminated against by the settlers; their belongings were seized by them without compensation. Many abuses occur, including enslaving of the ones who complain about the Wa government. They have to work in the fields with chained-up legs. When a minority person cannot give enough money to the rulers, they can sell children seven years or older as soldiers to the United Wa State Army. Due to these harsh living conditions, many had no other choice but to leave their hometowns.[24]

Geography and economy

[edit]

The region is mainly mountainous, with deep valleys. The lowest points are approximately 600 metres (2,000 ft) above sea level, with the highest mountains over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft).[citation needed] Initially Wa State was heavily reliant on opium production.[49] With Chinese assistance, there has been a move towards growing rubber and tea plantations.[50] Wa State cultivates 220,000 acres of rubber.[51] Due to the resettlement of residents from mountainous areas to fertile valleys,[52] there is also cultivation of wet rice, corn and vegetables. Dozens died during the resettlement due to disease and road accidents.[51] One of the main income sources of Wa State is the mining of resources like tin, zinc, lead and smaller amounts of gold.[53] The proven tin ore reserves of Wa State amount to more than 50 million tons, currently 95% of the tin mine production of Myanmar comes from there, around one sixth of the world production.[54][55]

Additionally, there is also a thriving industry around sectors like prostitution and gambling in the capital Pangkham that are related to tourism from China which was thriving before the COVID-19 pandemic.[56] The region was able to vaccinate nearly all of its population against the virus by July 2021, one of the earliest dates in the world.[57] In general, the state of development of Wa State is considerably higher than in the government-controlled areas of Myanmar, which is especially true for its capital.[56][58] Wa State is economically dependent on China, which supports it financially and provides military and civilian advisors and weapons.[59][60] It shares 82 miles (133 km) of frontier with China.[61]

The Myanmar kyat is not legal tender anywhere in the Wa State. In the north, the Chinese yuan is legal tender, whilst the baht is legal tender in the south.[62]

Illicit drug trade

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (February 2020) |

The United Wa State Army (UWSA) is among the largest narcotics trafficking organizations in Southeast Asia.[63]

The UWSA cultivated vast areas of land for the opium poppy, which was later refined to heroin. Methamphetamine trafficking was also important to the economy of Wa State.[51] The money from the opium was primarily used for purchasing weapons which continues to be the case to some extent. At the same time, while opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar had declined year-on-year since 2015, cultivation area increased by 33% totalling 40,100 hectares alongside an 88% increase in yield potential to 790 metric tonnes in 2022 according to latest data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Myanmar Opium Survey 2022[64] With that said, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has also warned that opium production in Myanmar may rise again if the economic crunch brought on by COVID-19 and the country's February 1 military coup persists, with significant public health and security consequences for much of Asia.[65]

In August 1990, government officials began drafting a plan to end drug production and trafficking in Wa State.[66] According to an interview with Wa officials in 1994, Bao Youyi (Tax Kuad Rang; also known as Bao Youyu) became wanted by the Chinese police for his involvement in drug trafficking. As a result, Bao Youxiang and Zhao Nyi-Lai went to Cangyuan Va Autonomous County of China and signed the Cangyuan Agreement with local officials, which stated that, "No drugs will go into the international society (from Wa State); no drugs will go into China (from Wa State); no drugs will go into Burmese government-controlled areas (from Wa State)."[67] However, the agreement did not mention whether or not Wa State could sell drugs to insurgent groups.

In 1997, the United Wa State Party officially proclaimed that Wa State would be drug-free by the end of 2005.[66] In 2005, Wa State authorities banned opium, and thereafter launched yearly drug crackdown campaigns.[22]: 54 With the help of the United Nations (which began opium-substitution programs in 1998)[22]: 174 and the Chinese government, many opium farmers in Wa State shifted to the production of rubber and tea. However, some poppy farmers continued to cultivate the flower outside of Wa State.[68] Anti-drug strategies involved opium substitution programs for farmers, seeking alternative revenue sources in the area, roadbuilding to improve access to the hills, strict enforcement, and a population resettlement program.[22]: 54 Between 1999 and 2006, the United Wa State Army began both voluntary resettlement and forced resettlement of between 50,000 and 100,000 villagers from the northern Wa State territory to the non-contiguous southern Wa State territory.[22]: 54 Malaria and travel-related deaths were significant among the relocated population.[22]: 54

Although opium cultivation in Myanmar declined from 1997 to 2006 on the whole, the opium ban in Wa State eventually led to increased production elsewhere in Myanmar as opium producers sought to benefit from rising opium prices following the ban.[22]: 174 From 2006 to 2012, overall opium cultivation in Myanmar doubled as production shifted to non-Wa State areas.[22]: 174

This population resettlement strategy relieved population pressures in the north Wa State hills and increased opportunities for the cultivation of rubber as an alternative cash crop to opium.[22]: 55 However, international commodity prices for rubber decreased radically by December 2012, fell to a low in November 2015, and remained low from 2015 to 2018.[22]: 56 Low rubber prices severely hampered Wa State's legitimate revenue and the income of rural people.[22]: 56

A BBC presentation aired on 19 November 2016 showed the burning of methamphetamine, as well as a thriving trade in illegal animal parts.[69]

The production of crystal meth of high quality as well as heroin is still thriving and worth billions of dollars as of 2021. Cheaper ya ba tablets are made by neighboring rebel groups which depend on the Wa for raw materials – namely precursor chemicals sourced from the chemical industry in China and chemical industry in India which enter Myanmar directly or by transit through the Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia) and specifically Lao PDR via Viet Nam and Thailand.[28][70] The regional synthetic drug production and trafficking industry, in which Wa State plays an important role, has become a major source of illegal drugs now exported across the region and beyond.[71][72][73][74]

See also

[edit]- Chinland, another self-governing polity in Myanmar

- Mang Lon

- Wa Women's Association

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Gray, Denis (12 August 2022). "From headhunting to weaponized drones: Myanmar's Wa carve own path". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 22 July 2024. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

Bertil Lintner, a Swedish author who is a leading authority on Myanmar, said Wa leaders have made no new political demands since the military seized control in Naypyitaw, such as a push for formal independence. An informal peace agreement between the Wa and the central government has lasted since 1989, giving the Wa self-government in return for recognition of Myanmar sovereignty.

- ^ a b Paliwal, Avinash (24 January 2024). "Could Myanmar Come Apart?". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

Though the state is nominally part of Myanmar, the Wa have their own political structures...

- ^ a b "UWSA Leader Vows to Continue Armed for Wa Autonomy". Burma News International. 18 April 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

"Wa State is a part of the Union of Burma and cannot be cut out of the union. We won't demand an independent Wa state or ask for secession."

- ^ a b 13 October 2011, 缅甸佤邦竟然是一个山寨版的中国 Archived 26 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 军情观察

- ^ a b c Kumbun, Joe (23 April 2019). "Protected by China, Wa Is Now a de Facto Independent State". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b c 29 December 2004, 佤帮双雄 Archived 25 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine, Phoenix TV.

- ^ a b c Steinmüller, Hans (2018). "Conscription by Capture in the Wa State of Myanmar: acquaintances, anonymity, patronage, and the rejection of mutuality" (PDF). London School of Economics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Hay, Wayne (29 September 2019). "Myanmar: No sign of lasting peace in Wa State". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ "Shan Herald Agency for News (S.H.A.N.)". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

'Officially, Bao Youxiang is still the President of the Wa State Government and Commander-in-Chief of the United Wa State Army,' said a Thai security officer, a ten-year veteran on the Thai-Burma border ...

- ^ voice of the FPNCC (FPNCC之声) (17 September 2022). 佤邦、掸邦东部第四特区及北掸邦第三特区三家友邻兄弟组织16日在邦康进行友好会谈 (in Chinese). “FPNCC之声”微信公众号. Archived from the original on 20 January 2024.

佤邦联合党中央政治局常委、佤邦政府副主席兼对外关系部部长赵国安,佤邦联合党中央政治局常委、佤邦政府副主席罗亚库

- ^ a b News Bureau of Wa State (佤邦新闻局) (13 January 2024). 佤邦人民政府就户板地区接管工作顺利完成 (in Chinese). “佤邦之音”微信公众号. Archived from the original on 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Wa Self-Administered Division WFP Myanmar". World Food Programme. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "缅甸佤邦竟然是一个山寨版的中国 – 军情观察". 26 November 2016. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016.

- ^ Horsey, Richard (31 May 2024). "Myanmar Is Fragmenting—but Not Falling Apart". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

Wa leaders accept that their territory is part of Myanmar, but they govern autonomously, maintaining an army strong enough to deter any attempt to bring the region under state control.

- ^ Maizland, Lindsay (22 February 2022). "Review: "The Wa of Myanmar and China's Quest for Global Dominance," by Bertil Lintner". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

The UWSA, by far the most powerful ethnic armed organization, controls an autonomous region within Myanmar's northeastern Shan State...

- ^ "Myanmar's Wa Army Vows Neutrality in Fight Between Regime, Ethnic Alliance". The Irrawaddy. 1 November 2023.

- ^ "တိုင်းခုနစ်တိုင်းကို တိုင်းဒေသကြီးများအဖြစ် လည်းကောင်း၊ ကိုယ်ပိုင်အုပ်ချုပ်ခွင့်ရ တိုင်းနှင့် ကိုယ်ပိုင်အုပ်ချုပ်ခွင့်ရ ဒေသများ ရုံးစိုက်ရာ မြို့များကို လည်းကောင်း ပြည်ထောင်စုနယ်မြေတွင် ခရိုင်နှင့်မြို့နယ်များကို လည်းကောင်း သတ်မှတ်ကြေညာ". Weekly Eleven News (in Burmese). 20 August 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ Sir J. George Scott, Burma : a handbook of practical information. London 1906, p.

- ^ N Ganesan; Kyaw Yin Hlaing, eds. (1 February 2007). Myanmar: State, Society and Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 269. ISBN 978-981-230-434-6.

- ^ 佤邦歷史 Archived 1 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Wa State government

- ^ "Regime schemes to cut support for Wa". Burma News International. Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ong, Andrew (2023). Stalemate: Autonomy and Insurgency on the China-Myanmar Border. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-7071-5. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctv2t8b78b.

- ^ Wa Local News Publications (8 November 2013). "Lox tat cub caw kuad song meung vax plak lai wa 04". Issuu. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d Unsettling Moves Archived 19 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Myanmar: Krieg mit Rebellen im Wa-Staat droht – entwicklungspolitik online". www.epo.de. 12 September 2009. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ "Welcome shanland.org - BlueHost.com". www.shanland.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Welcome shanland.org - BlueHost.com". www.shanland.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Wa an early winner of Myanmar's post-coup war". 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ "United Wa State Party calls for all parties to negotiate a ceasefire". nationthailand. 3 November 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar's Wa Army Vows Neutrality in Fight Between Regime, Ethnic Alliance". The Irrawaddy. 1 November 2023. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023.

- ^ Tensions High on Myanmar Border as Thai Troops Demand UWSA Withdrawal. The Irrawaddy. November 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c 13 October 2011, 缅甸佤邦竟然是一个山寨版的中国 Archived 26 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 军情观察

- ^ Interactive Myanmar Map Archived 8 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Stimson Center

- ^ Wa[usurped], Infomekong

- ^ General Background of the Wa[usurped]. Quote: "The official languages (designated by the current UWSP administration) are Mandarin and Wa."

- ^ 2009年9月, 不透明さ増すミャンマー情勢:2010年総選挙に向けて Archived 6 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, IDE-JETRO

- ^ 2011年11月15日, 地図にない街、ワ州潜入ルポが凄い『独裁者の教養』 Archived 30 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, エキサイトレビュー

- ^ "死刑前最后一刻曝光:3名中国人在缅甸劫杀同胞被枪决". 重庆晨报. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b Steinmüller, Hans (2018). "Conscription by Capture in the Wa State of Myanmar: acquaintances, anonymity, patronage, and the rejection of mutuality" (PDF). London School of Economics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Comms (21 April 2021). "Myanmar's CCP-Backed Wa State a Hostile Place for Christians". International Christian Concern. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Myanmar Ethnic Army Releases Detained Wa Christians". 5 October 2018. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ Htet, Thu (18 December 2019). "Wa Army Allows Churches to Reopen in Myanmar's Northern Shan State". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Yu, Pei-Hua (18 July 2021). "Chinese border crackdown forces citizens to leave Myanmar's 'Little China'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar's Wa, Mongla Fall on Hard Times Amid Chinese Exodus". 17 August 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Myanmar Military Bows to Powerful Ethnic Army, Gives it More Towns Near China Border". The Irrawaddy. 15 January 2024. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Xian, Yaolong (7 December 2022). "How Myanmar's United Wa State Army Responded to COVID-19". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ ""金三角"毒王 让缅、泰差点打起来". www.people.com.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Die Wa in Gefahr Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine (German)

- ^ ""Xinhua General News Service: China develops more substitute crops for opium poppy in bordering countries"". Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b c "Myanmar's strongest ethnic armed group says drug label 'not fair'". Reuters. 7 October 2016. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ BURMA NACHRICHTEN 4/2005, 25. Februar Archived 5 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (German). Quote: "Angaben der UN-Organisation zur Drogenbekämpfung UNODC und weiterer Beobachter zufolge droht durch die Ausführung des Plans zur Eliminierung des Opiumanbaus bis 2005 eine ernste humanitäre Krise der vom Opiumanbau abhängigen Bauern."

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (6 September 2019). "Myanmar's Wa hold the key to war and peace". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "The Wa state of Myanmar needs to be responsible for its own profits and losses. What does it rely on to develop its economy?". iNEWS. 23 July 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ "USGS Mineral Statistics". USGS. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Casinos and meth: the path to prosperity for Myanmar's remote narco-state". www.efe.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Guest Column | Silence on Coup Makes Strategic Sense for Myanmar's Wa". The Irrawaddy. 12 July 2021. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Life in Panghsang, a Chinese enclave in Myanmar's Wa region". 23 July 2019. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "西安此轮疫情1号确诊病例:核酸已转阴,CT病灶已消失-天津市酷派电动自行车有限公司". www-gatago.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012.

- ^ "World Politics Watch: On Myanmar-China border, tensions escalate between SPDC, narco-militias – Michael Black". Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "UWSA Talks Business, Drugs Cooperation with China". The Irrawaddy. 4 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Steinmüller, Hans (July 2019). "Conscription by Capture in the Wa State of Myanmar: Acquaintances, Anonymity, Patronage, and the Rejection of Mutuality". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 61 (3): 508–534. doi:10.1017/S0010417519000197. ISSN 0010-4175. S2CID 158812735.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil. "The United Wa State Army and Burma's Peace Process" (PDF). United States Institute of Peace. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar Opium Survey 2021: Cultivation, Production and Implications". February 2022.

- ^ "Myanmar's Economic Meltdown Likely to Push Opium Output Up, Says UN". 31 May 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b "记者亲历金三角腹地佤邦:毒品造就强大武装_资讯_凤凰网". Phoenix New Media (in Chinese). 26 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ China's dangerous neighbor Archived 27 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine Phoenix Weekly 2003

- ^ "China's Opium Substitution Policy in Burma and Laos – TransNational Institute" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Drugs, money and wildlife in Myanmar's most secret state". BBC News. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Douglas, Jeremy (19 August 2022). "Laos is a missing linkin Asia's fight against organized crime". CNN. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ Douglas, Jeremy (15 November 2018). "Parts of Asia are slipping into the hands of organized crime". CNN. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ Berlinger, Joshua (4 May 2021). "Asia's multibillion dollar methamphetamine cartels are using creative chemistry to outfox police, experts say". CNN. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ Douglas, Jeremy (8 June 2018). "Asia's new methamphetamine hotspot fueling regional unrest". CNN. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2019). "World Drug Report 2019". Retrieved 4 June 2025.

Sources

[edit]- Andrew Marshall, The Trouser People: a Story of Burma in the Shadow of the Empire. London: Penguin; Washington: Counterpoint, 2002. ISBN 1-58243-120-5.

- Ba Nyan, Who are the Wa? Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Enchen Lan, Promoting all Wa Townships in Shan State to Participate in Future Myanmar General Elections Archived 11 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Munich: GRIN Verlag, 2020. ISBN 9783346354228.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011). Traders of the Golden Triangle. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B006GMID5.

- Hideyuki Takano, The Shore Beyond Good and Evil: A Report from Inside Burma's Opium Kingdom (2002, Kotan, ISBN 0-9701716-1-7)

- Midnight in Burma. Ein Roman über die Tochter eines Generals im Wa-Staat, nicht gerade historisch mit vielen historischen Fehlern, aber sehr spannend geschrieben, Alex O'Brien. Asia Books ISBN 974-8303-58-6 (2001).

- The Wa State, Burma The National Strategy Forum Review Archived 11 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Wa leader: UWSA able to defend itself". panglong.org. Shan Herald. 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

External links

[edit]- Coordinates: 22°10′N 99°00′E / 22.167°N 99.000°E

- Television news broadcast from Wa State (in Chinese)

- 佤邦新闻 Wa State News's channel on YouTube (in Chinese) (in Tai languages)