Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

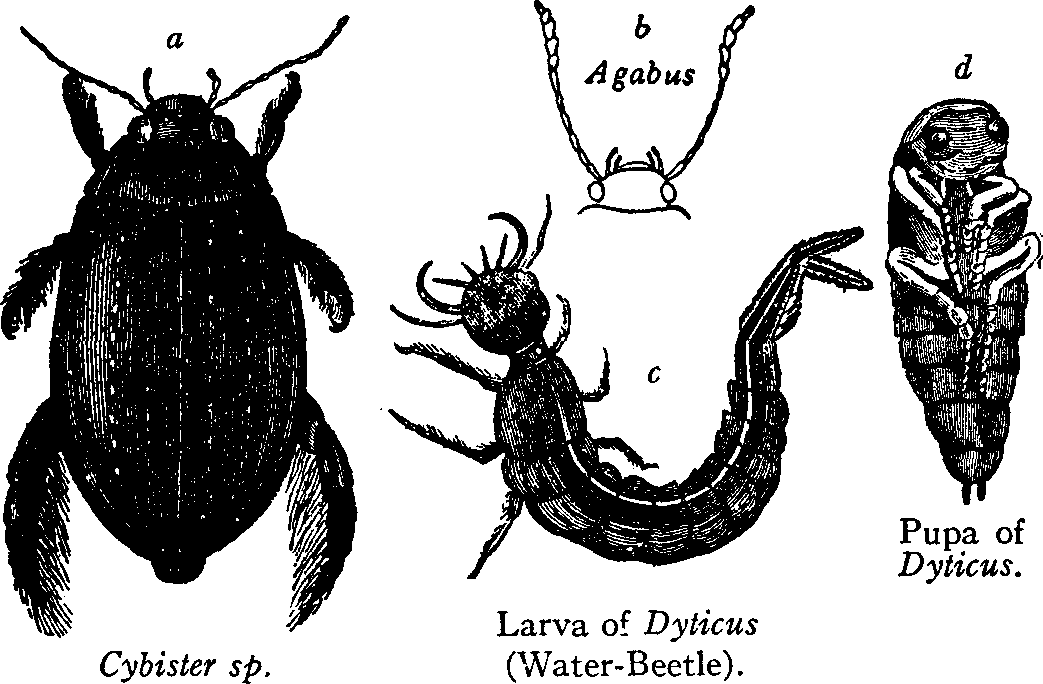

Water beetle

View on Wikipedia

A water beetle is a generalized name for any beetle that is adapted to living in water at any point in its life cycle. Most water beetles can only live in fresh water, with a few marine species that live in the intertidal zone or littoral zone. There are approximately 2000 species of true water beetles native to lands throughout the world.[1]

Many water beetles carry an air bubble, called the elytra cavity, underneath their abdomens, which provides an air supply, and prevents water from getting into the spiracles.[2] Others have the surface of their exoskeleton modified to form a plastron, or "physical gill", which permits direct gas exchange with the water. Some families of water beetles have fringed hind legs adapted for swimming, but most do not. Most families of water beetles have larvae that are also aquatic; many have aquatic larvae and terrestrial adults.[3][4]

Diet

[edit]Water beetles can be either herbivores, predators, or scavengers. Herbivorous beetles eat only aquatic vegetation, such as algae or leaves. They might also suck juices out the stem of a plant nearby. Scavenger beetles will feed on decomposing organic material that has been deposited. The scavenged material can come from aquatic vegetation, feces, or other small organisms that have died.[5] The great diving beetle, a predator, feeds on things like worms, tadpoles, and even sometimes small fish.[6]

Species

[edit]Families in which all species are aquatic in all life stages include:

- Dytiscidae

- Gyrinidae (Whirligig beetles)

- Haliplidae

- Noteridae

- Amphizoidae

- Hygrobiidae (Squeak beetles)

- Meruidae

- Hydroscaphidae (Skiff beetles).

Families in which the adults are not necessarily aquatic include:

- Hydrophilidae

- Lutrochidae (Travertine beetles)

- Dryopidae

- Elmidae

- Eulichadidae

- Heteroceridae

- Limnichidae

- Psephenidae (Water-penny beetles)

- Ptilodactylidae

- Torridincolidae

- Sphaeriusidae

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Water Beetle: pictures, information, classification and more". www.everythingabout.net.

- ^ "Water Beetle - Facts, Information & Pictures".

- ^ Peckarsky, Barbara Lynn (1990). Freshwater macroinvertebrates of northeastern North America. the University of Michigan: Comstock Pub. Associates. ISBN 0801420768.

- ^ McCafferty, W. Patrick (1983). Aquatic Entomology: The Fishermen's and Ecologists' Illustrated Guide to Insects and Their Relatives. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780867200171.

- ^ "Aquatic Beetles". EcoSpark. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Great Diving Beetle | The Wildlife Trusts". www.wildlifetrusts.org.

- Epler, J. H. 2010. The Water Beetles of Florida – an identification manual for the families Chrysomelidae, Curculionidae, Dryopidae, Dytiscidae, Elmidae, Gyrinidae, Haliplidae, Helophoridae, Hydraenidae, Hydrochidae, Hydrophilidae, Noteridae, Psephenidae, Ptilodactylidae and Scirtidae. Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Tallahassee, FL

Water beetle

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Classification

Families and Diversity

Water beetles constitute a polyphyletic assemblage of aquatic and semiaquatic species within the order Coleoptera, encompassing over 13,000 described species distributed across at least 23 families, primarily in the suborders Adephaga, Polyphaga, and Myxophaga.[1] This ecological guild reflects multiple independent transitions to aquatic lifestyles rather than descent from a single common ancestor.[1] The most species-rich families include Dytiscidae (predaceous diving beetles) with approximately 4,300 species, Hydrophilidae (water scavenger beetles) with about 2,950 species, and Elmidae (riffle beetles) with around 1,500 species.[1] Other notable families are Gyrinidae (whirligig beetles) with roughly 900 species, Hydraenidae (minute moss beetles) with approximately 1,600 species, and Haliplidae (crawling water beetles) with about 240 species.[1] Myxophaga is represented by smaller families such as Lepiceridae. These families account for the majority of water beetle diversity, with Adephaga hosting predatory groups like Dytiscidae, Gyrinidae, and Haliplidae, while Polyphaga includes scavenging and detritivorous taxa such as Hydrophilidae, Elmidae, and Hydraenidae.[1]| Family | Common Name | Approximate Species Count | Suborder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dytiscidae | Predaceous diving beetles | 4,300 | Adephaga |

| Hydrophilidae | Water scavenger beetles | 2,950 | Polyphaga |

| Elmidae | Riffle beetles | 1,500 | Polyphaga |

| Gyrinidae | Whirligig beetles | 900 | Adephaga |

| Hydraenidae | Minute moss beetles | 1,600 | Polyphaga |

| Haliplidae | Crawling water beetles | 240 | Adephaga |