Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

X Window System core protocol

View on Wikipedia

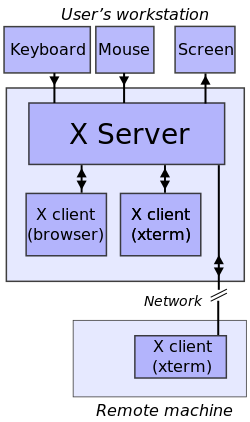

The X Window System core protocol[1][2][3] is the base protocol of the X Window System, which is a networked windowing system for bitmap displays used to build graphical user interfaces on Unix, Unix-like, and other operating systems. The X Window System is based on a client–server model: a single server controls the input/output hardware, such as the screen, the keyboard, and the mouse; all application programs act as clients, interacting with the user and with the other clients via the server. This interaction is regulated by the X Window System core protocol. Other protocols related to the X Window System exist, both built at the top of the X Window System core protocol or as separate protocols.

In the X Window System core protocol, only four kinds of packets are sent, asynchronously, over the network: requests, replies, events, and errors. Requests are sent by a client to the server to ask it to perform some operation (for example, create a new window) and to send back data it holds. Replies are sent by the server to provide such data. Events are sent by the server to notify clients of user activity or other occurrences they are interested in. Errors are packets sent by the server to notify a client of errors occurred during processing of its requests. Requests may generate replies, events, and errors; other than this, the protocol does not mandate a specific order in which packets are sent over the network. Some extensions to the core protocol exist, each one having its own requests, replies, events, and errors.

X originated at MIT in 1984 (its current[update] release X11 appeared in September 1987). Its designers Bob Scheifler and Jim Gettys set as an early principle that its core protocol was to "create mechanism, not policy". As a result, the core protocol does not specify the interaction between clients and between a client and the user. These interactions are the subject of separate specifications,[4] such as the ICCCM and the freedesktop.org specifications, and are typically enforced automatically by using a given widget set.

Overview

[edit]

Communication between server and clients is done by exchanging packets over a channel. The connection is established by the client (how the client is started is not specified in the protocol). The client also sends the first packet, containing the byte order to be used and information about the version of the protocol and the kind of authentication the client expects the server to use. The server answers by sending back a packet stating the acceptance or refusal of the connection, or with a request for a further authentication. If the connection is accepted, the acceptance packet contains data for the client to use in the subsequent interaction with the server.

After connection is established, four types of packets are exchanged between client and server over the channel:

- Request: The client requests information from the server or requests it to perform an action.

- Reply: The server responds to a request. Not all requests generate replies.

- Event: The server informs the client of an event, such as keyboard or mouse input, a window being moved, resized or exposed, etc.

- Error: The server sends an error packet if a request is invalid. Since requests are queued, error packets generated by a request may not be sent immediately.

Request and reply packets have varying length, while event and error packets have a fixed length of 32 bytes.

Request packets are numbered sequentially by the server as soon as it receives them: the first request from a client is numbered 1, the second 2, etc. The least significant 16 bits of the sequential number of a request is included in the reply and error packets generated by the request, if any. They are also included in event packets to indicate the sequential number of the request that the server is currently processing or has just finished processing.

Windows

[edit]What is usually called a window in most graphical user interfaces is called a top-level window in the X Window System. The term window is also used to denote windows that lie within another window, that is, the subwindows of a parent window. Graphical elements such as buttons, menus, icons, etc. can be realized using subwindows.

A client can request the creation of a window. More precisely, it can request the creation of a subwindow of an existing window. As a result, the windows created by clients are arranged in a tree (a hierarchy). The root of this tree is the root window, which is a special window created automatically by the server at startup. All other windows are directly or indirectly subwindows of the root window. The top-level windows are the direct subwindows of the root window. Visibly, the root window is as large as the virtual desktop, and lies behind all other windows.

The content of a window is not always guaranteed to be preserved over time. In particular, the window content may be destroyed when the window is moved, resized, covered by other windows, and in general made totally or partly non-visible. In particular, content is lost if the X server is not maintaining a backing store of the window content. The client can request backing store for a window to be maintained, but there is no obligation for the server to do so. Therefore, clients cannot assume that backing store is maintained. If a visible part of a window has an unspecified content, an event is sent to notify the client that the window content has to be drawn again.

Every window has an associated set of attributes, such as the geometry of the window (size and position), the background image, whether backing store has been requested for it, etc. The protocol includes requests for a client to inspect and change the attributes of a window.

Windows can be InputOutput or InputOnly. InputOutput windows can be shown on the screen and are used for drawing. InputOnly windows are never shown on the screen and are used only to receive input.

The decorative frame and title bar (possibly including buttons) that is usually seen around windows are created by the window manager, not by the client that creates the window. The window manager also handles input related to these elements, such as resizing the window when the user clicks and drags the window frame. Clients usually operate on the window they created disregarding the changes operated by the window manager. A change it has to take into account is that re-parenting window managers, which almost all modern window managers are, change the parent of top-level windows to a window that is not the root. From the point of view of the core protocol, the window manager is a client, not different from the other applications.

Data about a window can be obtained by running the xwininfo program. Passing it the -tree command-line argument, this program shows the tree of subwindows of a window, along with their identifiers and geometry data.

Pixmaps and drawables

[edit]A pixmap is a region of memory that can be used for drawing. Unlike windows, pixmaps are not automatically shown on the screen. However, the content of a pixmap (or a part of it) can be transferred to a window and vice versa. This allows for techniques such as double buffering. Most of the graphical operations that can be done on windows can also be done on pixmaps.

Windows and pixmaps are collectively named drawables, and their content data resides on the server. A client can however request the content of a drawable to be transferred from the server to the client or vice versa.

Graphic contexts and fonts

[edit]The client can request a number of graphic operations, such as clearing an area, copying an area into another, drawing points, lines, rectangles, and text. Beside clearing, all operations are possible on all drawables, both windows and pixmaps.

Most requests for graphic operations include a graphic context, which is a structure that contains the parameters of the graphic operations. A graphic context includes the foreground color, the background color, the font of text, and other graphic parameters. When requesting a graphic operation, the client includes a graphic context. Not all parameters of the graphic context affect the operation: for example, the font does not affect drawing a line.

The core protocol specifies the use of server-side fonts. Such fonts are stored as files, and the server accesses them either directly via the local filesystem or via the network from another program called font server. Clients can request the list of fonts available to the server and can request a font to be loaded (if not already) or unloaded (if not used by other clients) by the server. A client can request general information about a font (for example, the font ascent) and the space a specific string takes when drawn with a specific font.[citation needed]

xfontsel program allows the user to view the glyphs of a font.The names of the fonts are arbitrary strings at the level of the X Window core protocol. The X logical font description conventions[5] specify how fonts should be named according to their attributes. These conventions also specify the values of optional properties that can be attached to fonts.

The xlsfonts program prints the list of fonts stored in the server. The xfontsel program shows the glyphs of fonts, and allows the user to select the name of a font for pasting it in another window.

The use of server-side fonts is currently considered deprecated in favour of client-side fonts.[6] Such fonts are rendered by the client, not by the server, with the support of the Xft or cairo libraries and the XRender extension. No specification on client-side fonts is given in the core protocol.

Resources and identifiers

[edit]All data about windows, pixmaps, fonts, etc. are stored in the server. The client knows identifiers of these objects—integers it uses as names for them when interacting with the server. For example, if a client wishes a window to be created, it requests the server to create a window with a given identifier. The identifier can be later used by the client to request, for example, a string to be drawn in the window. The following objects reside in the server and are known by the client via a numerical identifier:

WindowPixmapFontColormap(a table of colors, described below)Graphic context

These objects are called resources. When a client requests the creation of one such resource, it also specifies an identifier for it. For example, for creating a new window, the client specifies both the attributes of the window (parent, width, height, etc.) and the identifier to associate with the window.

Identifiers are 32-bit integers with their three most significant bits equal to zero. Every client has its own set of identifiers it can use for creating new resources. This set is specified by the server as two integers included in the acceptance packet (the packet it sends to the client to inform it that the connection is accepted). Clients choose identifiers that are in this set in such a way they do not clash: two objects among windows, pixmaps, fonts, colormaps, and graphic contexts cannot have the same identifier.

Once a resource has been created, its identifier is used by the client to request operations about it to the server. Some operations affect the given resource (for example, requests to move windows); others ask for resource data stored from the server (for example, requests for the attributes of windows).

Identifiers are unique to the server, not only to the client; for example, no two windows have the same identifier, even if created by two different clients. A client can access any object given its identifier. In particular, it can also access resources created by any other client, even if their identifiers are outside the set of identifiers it can create.

As a result, two clients connected to the same server can use the same identifier to refer to the same resource. For example, if a client creates a window of identifier 0x1e00021 and passes this number 0x1e00021 to another application (via any available means, for example by storing this number in a file that is also accessible to the other application), this other application is able to operate on the very same window. This possibility is for example exploited by the X Window version of Ghostview: this program creates a subwindow, storing its identifier in an environment variable, and calls Ghostscript; this program draws the content of the PostScript file to show in this window.[7]

Resources are normally destroyed when the client that created them closes the connection with the server. However, before closing connection, a client can request the server not to destroy them.

Events

[edit]Events are packets sent by the server to a client to communicate that something the client may be interested in has happened. For example, an event is sent when the user presses a key or clicks a mouse button. Events are not only used for input: for example, events are sent to indicate the creation of new subwindows of a given window.

Every event is relative to a window. For example, if the user clicks when the pointer is in a window, the event will be relative to that window. The event packet contains the identifier of that window.

A client can request the server to send an event to another client; this is used for communication between clients. Such an event is for example generated when a client requests the text that is currently selected: this event is sent to the client that is currently handling the window that holds the selection.

The Expose event is sent when an area of a window of destroyed and content is made visible. The content of a window may be destroyed in some conditions, for example, if the window is covered and the server is not maintaining a backing store. The server generates an Expose event to notify the client that a part of the window has to be drawn.

Most kinds of events are sent only if the client previously stated an interest in them. This is because clients may only be interested in some kind of events. For example, a client may be interested in keyboard-related events but not in mouse-related events. Some kinds of events are however sent to clients even if they have not specifically requested them.

Clients specify which kinds of events they want to be sent by setting an attribute of a window. For example, in order to redraw a window when its content has been destroyed, a client must receive the Expose events, which inform it that the window needs to be drawn again. The client will however be sent Expose events only if the client has previously stated its interest in these events, which is done by appropriately setting the event mask attribute of the window.

Different clients can request events on the same window. They can even set different event masks on the same window. For example, a client may request only keyboard events on a window while another client requests only mouse events on the same window. This is possible because the server, for each window, maintains a separate event mask for each client. However, there are some kinds of events that can only be selected by one client at time for each window. In particular, these events report mouse button clicks and some changes related to window management.

The xev program shows the events relative to a window. In particular, xev -id WID requests all possible events relative to the window of identifier WID and prints them.

Example

[edit]The following is a possible example of interaction between a server and a program that creates a window with a black box in it and exits on a keypress. In this example, the server does not send any reply because the client requests do not generate replies. These requests could generate errors.

- The client opens the connection with the server and sends the initial packet specifying the byte order it is using.

- The server accepts the connection (no authorization is involved in this example) by sending an appropriate packet, which contains other information such as the identifier of the root window (e.g.,

0x0000002b) and which identifiers the client can create. - The client requests the creation of a default graphic context with identifier

0x00200000(this request, like the other requests of this example, does not generate replies from the server) - The client requests the server to create a top-level window (that is, it specifies the parent to be the root window

0x0000002b) with identifier0x00200001, size 200x200, position (10,10), etc. - The client requests a change in the attributes of the window

0x00200001, specifying it is interested in receivingExposeandKeyPressevents. - The client requests the window

0x00200001to be mapped (shown on the screen) - When the window is made visible and its content has to be drawn, the server sends the client an

Exposeevent - In response to this event, the client requests a box to be drawn by sending a

PolyFillRectanglerequest with window0x00200001and graphic context0x00200000

If the window is covered by another window and uncovered again, assuming that backing store is not maintained:

- The server sends another

Exposeevent to tell the client that the window has to be drawn again - The client redraws the window by sending a

PolyFillRectanglerequest

If a key is pressed:

- The server sends a

KeyPressevent to the client to notify it that the user has pressed a key - The client reacts appropriately (in this case, it terminates)

Colors

[edit]At the protocol level, a color is represented by a 32-bit unsigned integer, called a pixelvalue. The following elements affect the representation of colors:

- the color depth

- the colormap, which is a table containing red, green, and blue intensity values

- the visual type, which specifies how the table is used to represent colors

In the easiest case, the colormap is a table containing a RGB triple in each row. A pixelvalue x represents the color contained in the x-th row of the table. If the client can change the entries in the colormap, this representation is identified by the PseudoColor visual class. The visual class StaticColor is similar, but the client cannot change the entries in the colormap.

There are a total of six possible visual classes, each one identifying a different way for representing an RGB triple with a pixelvalue. PseudoColor and StaticColor are two. Another two are GrayScale and StaticGray, which differ in that they only display shades of grey.

The two remaining visual classes differ from the ones above because they break pixelvalues in three parts and use three separate tables for the red, green, and blue intensity. According to this color representation, a pixelvalue is converted into an RGB triple as follows:

- the pixelvalue is seen as a sequence of bits

- this sequence is broken in three parts

- each of these three chunks of bits is seen as an integer and used as an index to find a value in each of three separate tables

This mechanism requires the colormap to be composed of three separate tables, one for each primary color. The result of the conversion is still a triple of intensity values. The visual classes using this representation are the DirectColor and TrueColor ones, differing on whether the client can change colormaps or not.

These six mechanisms for representing colors with pixelvalues all require some additional parameters to work. These parameters are collected into a visual type, which contains a visual class and other parameters of the representation of colors. Each server has a fixed set of visualtypes, each one associated with a numerical identifier. These identifiers are 32-bit unsigned integers, but are not necessarily different from identifiers of resources or atoms.

When the connection from a client is accepted, the acceptance packet sent by the server contains a sequence of blocks, each one containing information about a single screen. For each screen, the relative block contains a list of other blocks, each one relative to a specific color depth that is supported by the screen. For each supported depth, this list contains a list of visualtypes. As a result, each screen is associated a number of possible depths, and each depth of each screen is associated a number of possible visual types. A given visual type can be used for more screens and for different depths.

For each visual type, the acceptance packet contains both its identifier and the actual parameters it contains (visual class, etc.) The client stores this information, as it cannot request it afterwards. Moreover, clients cannot change or create new visual types. Requests for creation of a new window include the depth and the identifier of the visual type to use for representing colors of this window.

Colormaps are used regardless of whether the hardware controlling the screen (e.g., a graphic card) uses a palette, which is a table that is also used for representing colors. Servers use colormaps even if the hardware is not using a palette. Whenever the hardware uses palettes, only a limited number of colormaps can be installed. In particular, a colormap is installed when the hardware shows colors according to it. A client can request the server to install a colormap. However, this may require the uninstalling of another colormap: the effect is that windows using the uninstalled colormap are not shown with the correct color, an effect dubbed color flashing or technicolor. This problem can be solved using standard colormaps, which are colormaps with a predictable association between pixelvalues and colors. Thanks to this property, standard colormaps can be used by different applications.

The creation of colormaps is regulated by the ICCCM convention. Standard colormaps are regulated by the ICCCM and by the Xlib specification.

A part of the X colour system is the X Color Management System (xcms). This system was introduced with X11R6 Release 5 in 1991. This system consists of several additional features in xlib, found in the Xcms* series of functions. This system defines device independent color schemes which can be converted into device dependent RGB systems. The system consists of the xlib Xcms* functions and as well the X Device Color Characterization Convention (XDCCC) which describes how to convert the various device independent colour systems into device dependent RGB colour systems. This system supports the CIEXYZ, xyY, CIELUV and CIELAB and as well the TekHVC colour systems. [1] Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, [2]

Atoms

[edit]Atoms are 32-bit integers representing strings. The protocol designers introduced atoms because they represent strings in a short and fixed size:[8] while a string may be arbitrarily long, an atom is always a 32-bit integer. Atom brevity was exploited by mandating their use in the kinds of packets that are likely to be sent many times with the same strings; this results in a more efficient use of the network. The fixed size of atoms was exploited by specifying a fixed size for events, namely 32 bytes: fixed-size packets can contain atoms, while they cannot contain long strings.

Precisely, atoms are identifiers of strings stored in the server. They are similar to the identifiers of resources (Windows, Pixmaps, etc.) but differ from them in two ways. First, the identifiers of atoms are chosen by the server, not by the client. In other words, when a client requests the creation of a new atom, it only sends the server the string to be stored, not its identifier; this identifier is chosen by the server and sent back as a reply to the client. The second important difference between resources and atoms is that atoms are not associated with clients. Once created, an atom survives until the server quits or resets (this is not the default behavior of resources).

Atoms are identifiers and are therefore unique. However, an atom and a resource identifier can coincide. The string associated with an atom is called the atom name. The name of an atom cannot be changed after creation, and no two atoms can have the same name. As a result, the name of an atom is commonly used to indicate the atom: “the atom ABCD” means, more precisely, “the atom whose associated string is ABCD.” or “the atom whose name is ABCD.” A client can request the creation of a new atom and can request for the atom (the identifier) of a given string. Some atoms are predefined (created by the server with given identifier and string).

Atoms are used for a number of purposes, mostly related to communication between different clients connected to the same server. In particular, they are used in association with the properties of windows, which are described below.

The list of all atoms residing in a server can be printed out using the program xlsatoms. In particular, this program prints each atom (the identifier, that is, a number) with its name (its associated string).

Properties

[edit]Every window has a predefined set of attributes and a set of properties, all stored in the server and accessible to the clients via appropriate requests. Attributes are data about the window, such as its size, position, background color, etc. Properties are arbitrary pieces of data attached to a window. Unlike attributes, properties have no meaning at the level of the X Window core protocol. A client can store arbitrary data in a property of a window.

A property is characterized by a name, a type, and a value. Properties are similar to variables in imperative programming languages, in that a client can create a new property with a given name and type and store a value in it. Properties are associated to windows: two properties with the same name can exist on two different windows while having different types and values.

The name, type, and value of a property are strings; more precisely, they are atoms, that is, strings stored in the server and accessible to the clients via identifiers. A client application can access a given property by using the identifier of the atom containing the name of the property.

Properties are mostly used for inter-client communication. For example, the property named WM_NAME (the property named by the atom whose associated string is "WM_NAME") is used for storing the name of windows. Window managers typically read this property to display the name of windows in their title bar.

Some types of inter-client communication use properties of the root window. For example, according to the freedesktop window manager specification,[9] window managers should store the identifier of the currently active window in the property named _NET_ACTIVE_WINDOW of the root window. The X resources, which contain parameters of programs, are also stored in properties of the root window; this way, all clients can access them, even if running on different computers.

The xprop program prints the properties of a given window; xprop -root prints the name, type, and value of each property of the root window.

Mappings

[edit]

/, 7, and { are associated to three different keysyms.In the X Window System, every individual, physical key is associated a number in the range 8–255, called its keycode. A keycode only identifies a key, not a particular character or term (e.g., "Page Up") among the ones that may be printed on the key. Each one of these characters or terms is instead identified by a keysym. While a keycode only depends on the actual key that is pressed, a keysym may depend, for example, on whether the Shift key or another modifier was also pressed.

When a key is pressed or released, the server sends events of type KeyPress or KeyRelease to the appropriate clients. These events contain:

- the keycode of the pressed key

- the current state of the modifiers (Shift, Control, etc.) and mouse buttons

The server therefore sends the keycode and the modifier state without attempting to translate them into a specific character. It is a responsibility of the client to do this conversion. For example, a client may receive an event stating that a given key has been pressed while the Shift modifier was down. If this key would normally generate the character "a", the client (and not the server) associates this event to the character "A".

While the translation from keycodes to keysyms is done by the client, the table that represents this association is maintained by the server. Storing this table in a centralized place makes it accessible to all clients. Typical clients only request this mapping and use it for decoding the keycode and modifiers field of a key event into a keysym. However, clients can also change this mapping at will.

A modifier is a key that, when pressed, changes the interpretation of other keys. A common modifier is the Shift key: when the key that normally produces a lowercase "a" is pressed together with Shift, it produces an uppercase "A". Other common modifiers are "Control", "Alt", and "Meta".

The X server works with at most eight modifiers. However, each modifier can be associated with more than one key. This is necessary because many keyboards have duplicated keys for some modifiers. For example, many keyboards have two "Shift" keys (one on the left and one on the right). These two keys produce two different keycodes when pressed, but the X server associates both with the "Shift" modifier.

For each of the eight modifiers, the X server maintains a list of the keycodes that it consider to be that modifier. As an example, if the list of the first modifier (the "Shift" modifier) contains the keycode 0x37, then the key that produces the keycode 0x37 is considered a shift key by the X server.

The lists of modifier mappings is maintained by the X server but can be changed by every client. For example, a client can request the "F1 key" to be added to the list of "Shift" modifiers. From this point on, this key behaves like another shift modifier. However, the keycode corresponding to F1 is still generated when this key is pressed. As a result, F1 operates as it did before (for example, a help window may be opened when it is pressed), but also operates like the shift key (pressing "a" in a text editor while F1 is down adds "A" to the current text).

The X server maintains and uses a modifier mapping for the mouse buttons. However, the buttons can only be permuted. This is mostly useful for exchanging the leftmost and rightmost button for left-handed users.

The xmodmap program shows and changes the key, modifier, and mouse button mappings.

Grabs

[edit]A grab is a condition in which all keyboard or mouse events are sent to a single client. A client can request a grab of the keyboard, the mouse, or both: if the request is fulfilled by the server, all keyboard/mouse events are sent to the grabbing client until the grab is released. The other clients will not receive these events.

When requesting a grab, a client specifies a grab window: all events are sent to the grabbing client as if they were relative to the grab window. However, the other clients do not receive events even if they have selected them in the grab window. There are two kinds of grabs:

- active: the grab takes place immediately

- passive: the grab takes place only when a previously specified key or mouse button is pressed and terminates when it is released

A client can establish a grab over the keyboard, the pointer, or both. A request for grabbing can include a request for freezing the keyboard or the pointer. The difference between grabbing and freezing is that grabbing changes the recipient of events, while freezing stops their delivery altogether. When a device is frozen, the events it generates are stored in a queue to be delivered as usual when the freeze is over.

For pointer events, an additional parameter affects the delivery of events: an event mask, which specifies which types of events are to be delivered and which ones are to be discarded.

The requests for grabbing include a field for specifying what happens to events that would be sent to the grabbing client even if it had not established the grab. In particular, the client can request them to be sent as usual or according to the grab. These two conditions are not the same as they may appear. For example, a client that would normally receive the keyboard events on a first window may request the keyboard to be grabbed by a second window. Events that would normally be sent to the first window may or may not be redirected to the grab window depending on the parameter in the grab request.

A client can also request the grab of the entire server. In this case, no request will be processed by the server except the ones coming from the grabbing client.

Other

[edit]Other requests and events in the core protocol exist. The first kind of requests is relative to the parent relationship between windows: a client can request to change the parent of a window, or can request information about the parenthood of windows. Other requests are relative to the selection, which is however mostly governed by other protocols. Other requests are about the input focus and the shape of the pointer. A client can also request the owner of a resource (window, pixmap, etc.) to be killed, which causes the server to terminate the connection with it. Finally, a client can send a no-operation request to the server.

Extensions

[edit]

The X Window core protocol was designed to be extensible. The core protocol specifies a mechanism for querying the available extensions and how extension requests, events, and errors packets are made.

In particular, a client can request the list of all available extensions for data relative to a specific extension. The packets of extensions are similar to the packets of the core protocol. The core protocol specifies that request, event, and error packets contain an integer indicating its type (for example, the request for creating a new window is numbered 1). A range of these integers are reserved for extensions.

Authorization

[edit]When the client initially establishes a connection with the server, the server can reply by either accepting the connection, refusing it, or requesting authentication. An authentication request contains the name of the authentication method to use. The core protocol does not specify the authentication process, which depends on the kind of authentication used, other than it ends with the server either sending an acceptance or a refusal packet.

During the regular interaction between a client and a server, the only requests related to authentication are about the host-based access method. In particular, a client can request this method to be enabled and can request reading and changing the list of hosts (clients) that are authorized to connect. Typical applications do not use these requests; they are used by the xhost program to give a user or a script access to the host access list. The host-based access method is considered insecure.

Xlib and other client libraries

[edit]Most client programs communicate with the server via the Xlib client library. In particular, most clients use libraries such as Xaw, Motif, GTK+, or Qt which in turn use Xlib for interacting with the server. The use of Xlib has the following effects:

- Xlib makes the client synchronous with respect to replies and events:

- the Xlib functions that send requests block until the appropriate replies, if any is expected, are received; in other words, an X Window client not using Xlib can send a request to the server and then do other operations while waiting for the reply, but a client using Xlib can only call an Xlib function that sends the request and wait for the reply, thus blocking the client while waiting for the reply (unless the client starts a new thread before calling the function);

- while the server sends events asynchronously, Xlib stores events received by the client in a queue; the client program can only access them by explicitly calling functions of the X11 library; in other words, the client is forced to block or busy-wait if expecting an event.

- Xlib does not send requests to the server immediately, but stores them in a queue, called the output buffer; the requests in the output buffer are actually sent when:

- the program explicitly requests so by calling a library function such as

XFlush; - the program calls a function that gives as a result something that involve a reply from the server, such as

XGetWindowAttributes; - the program asks for an event in the event queue (for example, by calling

XNextEvent) and the call blocks (for example,XNextEventblocks if the queue is empty.)

- the program explicitly requests so by calling a library function such as

Higher-level libraries such as Xt (which is in turn used by Xaw and Motif) allow the client program to specify the callback functions associated with some events; the library takes care of polling the event queue and calling the appropriate function when required; some events such as those indicating the need of redrawing a window are handled internally by Xt.

Lower-level libraries, such as XCB, provide asynchronous access to the protocol, allowing better latency hiding.

Unspecified parts

[edit]The X Window System core protocol does not mandate over inter-client communication and does not specify how windows are used to form the visual elements that are common in graphical user interfaces (buttons, menus, etc.). Graphical user interface elements are defined by client libraries realizing widget toolkits. Inter-client communication is covered by other standards such as the ICCCM and freedesktop specifications.[9]

Inter-client communication is relevant to selections, cut buffers, and drag-and-drop, which are the methods used by a user to transfer data from a window to another. Since the windows may be controlled by different programs, a protocol for exchanging this data is necessary. Inter-client communication is also relevant to X window managers, which are programs that control the appearance of the windows and the general look-and-feel of the graphical user interface.

Session management

[edit]Yet another issue where inter-client communication is to some extent relevant is that of session management.

How a user session starts is another issue that is not covered by the core protocol. Usually, this is done automatically by the X display manager. The user can however also start a session manually running the xinit or startx programs.

See also

[edit]- X Window System protocols and architecture

- Xlib

- Intrinsics

- Xnee can be used to sniff the X Window System protocol

References

[edit]- ^ Robert W. Scheifler and James Gettys: X Window System: Core and extension protocols, X version 11, releases 6 and 6.1, Digital Press 1996, ISBN 1-55558-148-X

- ^ RFC 1013

- ^ Grant Edwards. An Introduction to X11 User Interfaces Archived 2007-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jim Gettys. Open Source Desktop Technology Road Map Archived January 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jim Flowers; Stephen Gildea (1994). "X Logical Font Description Conventions" (PDF). Digital Equipment Corporation. X Consortium. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2005. Retrieved 2005-12-30.

- ^ Matthieu Herrb and Matthias Hopf. New Evolutions in the X Window System.

- ^ "Interface with ghostscript - GNU gv Manual". www.gnu.org.

- ^ David Rosenthal. Inter-Client Communication Conventions Manual. MIT X Consortium Standard, 1989

- ^ a b "wm-spec". www.freedesktop.org.

External links

[edit]- X.Org Foundation (official home page) - Mirror with the domain name 'freedesktop.org'.

- X Window System Internals

- Kenton Lee's pages on X Window and Motif Archived 2013-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- X Window System Protocol, Version 11 (current Release)

X Window System core protocol

View on GrokipediaProtocol Fundamentals

Overview

The X Window System core protocol serves as the base communication protocol for the X11 windowing system, enabling a client-server model for graphics rendering and input handling across networked bitmap displays. Developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1984 as part of Project Athena—a collaborative effort between MIT, DEC, and IBM to advance distributed computing in education—it originated from work by Robert W. Scheifler and Jim Gettys to address the need for a portable, network-aware graphical interface.[4][5] The protocol evolved from the experimental X10 version released in 1985 to X11 on September 15, 1987, which introduced greater stability and hardware independence while preserving backward compatibility.[6] Standardization followed through the X Consortium (formed in 1988 and later succeeded by the X.Org Foundation), with key inter-client conventions defined in documents like the Inter-Client Communication Conventions Manual (ICCM) to ensure consistent behavior across applications.[7] This evolution solidified X11 as the enduring foundation for Unix-like systems, emphasizing simplicity and extensibility over rigid policy.[5] Central design principles include network transparency, which allows remote clients to access local display resources seamlessly; strict client-server separation, where clients issue commands without direct hardware control; an event-driven paradigm for asynchronous notifications on input and changes; and resource management via opaque 32-bit identifiers (XIDs) to track entities like windows and fonts.[5] In its architecture, the X server manages display hardware, keyboards, mice, and multiple screens, processing client requests transmitted over TCP/IP or Unix domain sockets, while replying with data or generating events as needed.[1] Core abstractions such as windows and events underpin this model, facilitating hierarchical graphics and reactive input handling.[5] Version 11 of the core protocol defines requests using major opcodes 0–127 (approximately 120 defined), many of which generate replies; 33 event types covering input and exposure notifications; and 17 error types for handling invalid operations.[1][8]Connections and Communication

The X Window System core protocol establishes communication between clients and the server over a network connection, typically using TCP/IP on port 6000 plus the display number.[1] To initiate a connection, the client first transmits a single byte indicating the byte order for multi-byte data: octal 102 for most significant byte first (big-endian) or 154 for least significant byte first (little-endian).[9] The client then sends a 12-byte setup message containing the protocol major and minor version numbers—typically 11 for the major and 0 for the minor in the standard X11 version—followed by the authorization protocol name and data as STRING8 sequences.[9] Authentication occurs during this handshake; if no authorization is required, the name and data fields are empty, but for secure connections, mechanisms like the xauth protocol (using MIT-MAGIC-COOKIE-1) are employed, where the client provides a shared secret cookie managed by the xauth utility.[9][10] The server responds with a 8-byte or longer message indicating success (or failure reasons like authentication failure), the accepted protocol version, release number, resource identifier base and mask for generating XIDs, along with vendor string, supported formats, and image byte order.[9] All communication consists of fixed- or variable-length messages exchanged in a request-reply model, with asynchronous events and errors interspersed.[11] Requests are one-way messages from client to server, comprising an 8-bit major opcode (0-127 for core, 128-255 for extensions), data specific to the request, and a 16-bit length field in units of 4 bytes; they do not receive replies unless specified, such as for GetWindowAttributes which solicits a reply with window properties.[11] Replies from the server are 32 bytes fixed plus optional data, including a 32-bit length, the requested information, and a 16-bit sequence number matching the original request.[12] Events serve as asynchronous notifications from server to client, formatted as 32-byte fixed structures with an 8-bit type code (0-63 for core events, 64-127 reserved for extensions), detail data, sequence number, and optional padding; timestamps in events are CARD32 values representing milliseconds since the server started or reset.[13] Errors are 32-byte messages indicating protocol violations, featuring an 8-bit error code (1-17 for core, such as BadRequest=1 or BadWindow=3, with 128-255 for extensions), the offending major opcode, and sequence number.[14] The protocol defines basic data types to ensure consistent interpretation across byte orders, including BYTE for 8-bit values, CARD32 for 32-bit unsigned integers, STRING8 for null-terminated 8-bit character sequences (padded to even bytes if needed), and STRING16 for 16-bit character sequences using CHAR2B pairs.[15] Messages incorporate fixed-length fields for headers and variable-length lists (e.g., LISTofINTEGER as repeated CARD32), with all structures padded to multiples of 4 bytes for alignment, using pad bytes (0x00) as necessary.[11] Sequence numbers, assigned incrementally starting from 1 for each request on a connection, ensure ordering and synchronization; events and errors include both the request sequence number that triggered them and the server's last processed sequence for compression hints, allowing clients to discard redundant motion events if a later one arrives.[16] Error handling distinguishes protocol errors, which are synchronous or asynchronous responses to invalid requests (e.g., BadValue=2 for out-of-range parameters), from I/O errors like connection timeouts or closures.[17] Upon connection close—initiated by client via CloseConnection request or server via abrupt termination—all resources allocated on that connection, such as windows and pixmaps identified by XIDs, are automatically destroyed unless explicitly saved in a save-set; atoms and server-wide properties persist until a server reset.[18] Clients must handle errors by checking codes and sequence numbers to identify affected operations, with no automatic retry mechanism in the core protocol.[17]Resources and Identifiers

In the X Window System core protocol, resources such as windows, pixmaps, and graphic contexts are identified using 32-bit unsigned integers known as XIDs (X Window Identifiers), which serve as opaque handles for referencing server-side objects across the client-server boundary. These XIDs are allocated either by the client, which generates values by selecting a subset of bits within a server-provided mask and ORing them with a base value (ensuring the top three bits are never set and at least 18 bits are available for allocation), or by the server, which may reassign an XID if the client's choice is invalid, conflicting, or outside the permitted range of 0 to 2³²-1. Once allocated, an XID remains unique across all active resources on the server until the associated resource is destroyed, after which the identifier can be reused for new allocations.[19] Resource types in the protocol are categorized into implicit classes, such as windows and pixmaps, where the type is inherent to the creation request, and explicit classes, such as fonts, cursors, and colormaps, which require specification of a class identifier during allocation. Clients can query available resources and their identifiers using protocol requests tailored to each type, such as ListFonts for font identifiers or QueryExtension for extension-related resources, though the core protocol does not provide a generic ListIDs mechanism. This distinction ensures that resource creation and management remain type-specific while maintaining a unified identifier namespace. XIDs are also briefly referenced in events (e.g., as the window ID in Expose events) and properties (e.g., atom-based property identifiers), facilitating indirect resource interactions without exposing implementation details.[19][3] The lifetime of resources is managed entirely on the server side, where they persist until explicitly destroyed by the client via dedicated requests (e.g., DestroyWindow for windows) or until the client connection is terminated, at which point all associated resources are automatically freed. Clients do not maintain server-side state beyond the XIDs themselves, and identifier mapping between client and server accounts for potential mismatches due to network transparency, with the server enforcing validity without requiring client-side caching of resource details. This design promotes robustness in distributed environments, as clients need only track XIDs locally while relying on the server for actual resource persistence and deallocation.[19] To prevent resource exhaustion, the server enforces configurable limits on the maximum number of resources per client connection, typically determined at server startup or via configuration. Attempts to allocate beyond these limits result in a BadAlloc error (error code 11), signaling that the request cannot proceed due to insufficient server resources. This mechanism balances scalability and security, allowing servers to tailor resource quotas without altering the core protocol semantics.[19]Graphical Primitives

Windows

In the X Window System core protocol, windows serve as the fundamental visible containers for graphical output and input handling, organized in a hierarchical tree structure that reflects the spatial relationships on the display screen.[1] The root window, created automatically by the server for each screen, forms the top of this hierarchy and covers the entire screen surface, with a class of InputOutput and depth and visual attributes matching the screen's default.[1] Child windows are created relative to a parent window, enabling a nested organization where each window's position is defined within its parent's coordinate space.[1] Window creation occurs through the CreateWindow request, which specifies a unique window identifier (XID) for the new window, the parent window's XID, position coordinates (x, y as INT16 values), dimensions (width, height, and border-width as CARD16 values), class (either InputOutput or InputOnly), depth (CARD8, or CopyFromParent to inherit from the parent), and visual ID (VISUALID or CopyFromParent).[1] The newly created window remains unmapped and invisible until explicitly mapped.[1] For InputOutput windows, the depth and visual must be compatible with the parent's screen, allowing them to store pixel data and serve as drawables for graphics; in contrast, InputOnly windows have a fixed depth of 0, cannot store pixels or overlap with pixmaps, and are restricted to input event handling without rendering capabilities.[1] The window hierarchy supports dynamic reorganization via the ReparentWindow request, which reassigns a window to a new parent at specified coordinates (x, y), provided the new parent is of the same generation and not an ancestor to avoid cycles.[1] Visibility is managed through mapping and unmapping: the MapWindow request makes a window and its descendants visible (if not obscured), while UnmapWindow hides them, with both operations generating corresponding event notifications for clients.[1] These changes in the hierarchy can trigger events such as MapNotify or UnmapNotify to inform interested clients.[1] Windows possess a set of configurable attributes that control their behavior, storage, and interaction, which can be modified using the ChangeWindowAttributes request via a value-mask and corresponding value-list, or queried through the GetWindowAttributes reply.[1] Key attributes include the backing store hint (NotUseful for no maintenance, WhenMapped for updates only when visible, or Always for full preservation of contents), bit gravity (e.g., NorthWest to reposition exposed bits during resizing), and win gravity (e.g., Static to keep the window position fixed relative to the parent).[1] Event masks define client subscriptions to events like Exposure or KeyPress, while the do-not-propagate-mask prevents certain device events (e.g., key presses) from passing to ancestors.[1] Additional attributes encompass the cursor (CURSOR ID or None to inherit from parent), colormap (COLORMAP ID or CopyFromParent for color mapping), save-under (BOOL to request temporary preservation under pop-ups), override-redirect (BOOL to bypass window manager control), and map state (Unmapped, Unviewable, or Viewable).[1] These attributes ensure flexible management of window appearance and responsiveness within the protocol's client-server model.[1]Pixmaps and Drawables

In the X Window System core protocol, a drawable is defined as a server resource that serves as a destination for graphics requests, encompassing both windows and pixmaps to provide a unified abstraction for rendering operations.[1] This abstraction allows graphics primitives, such as drawing lines or filling rectangles, to target any drawable without distinguishing between on-screen windows and off-screen storage.[1] Pixmaps represent off-screen drawables, implemented as a three-dimensional array of bits allocated by the server for storing pixel data independently of the display hierarchy.[1] To create a pixmap, the client issues a CreatePixmap request specifying a resource identifier (pid), a parent drawable to determine the root window and supported depth, along with the desired width, height (both CARD16 values, nonzero), and depth (CARD8).[1] The server then allocates the necessary memory, with the pixmap's depth matching one of the depths supported by the specified root window's visual; errors such as Alloc, Match, or Value may occur if parameters are invalid.[1] Pixmaps persist until explicitly destroyed via the FreePixmap request, which releases the resource identifier and associated storage once no references remain, potentially triggering a Pixmap error if the identifier is invalid.[1] Key operations on pixmaps and drawables include CopyArea and CopyPlane, which facilitate efficient bit-block transfer (bitblt) between drawables.[1] The CopyArea request copies a rectangular region of pixels from a source drawable to a destination drawable, using a graphics context (GC) for clipping and transformation, with parameters including source and destination coordinates (INT16), dimensions (CARD16), and requiring matching root and depth to avoid Match errors.[1] Similarly, CopyPlane extends this by copying a single bit plane from the source, mapping it to foreground and background pixels in the destination via the GC, specified by a bit-plane mask (CARD32).[1] These operations treat pixmaps as versatile sources or sinks, such as for compositing images or implementing double-buffering. Pixmaps are characterized by their depth—the number of bits per pixel. When reading or writing image data to pixmaps via requests like GetImage or PutImage, the format can be specified as ZPixmap (linear scanline order) or XYPixmap (plane-interleaved), with scanline padding to align to 8, 16, or 32 bits for efficiency.[1] The depth must align with the parent drawable's visual, enabling pixmaps to serve specialized roles like cursor images (depth 1 bitmaps) or window backgrounds, while the root window acts as a universal drawable parent for creating pixmaps compatible across the screen.[1] Unlike windows, pixmaps lack event processing, input handling, or hierarchical relationships, existing solely as flat, persistent storage freed only on explicit request, which makes them ideal for temporary rendering targets in bitblt workflows.[1] Drawing requests, such as PolyLine or FillPolygon, can target drawables directly to render content onto pixmaps before transfer to visible windows.[1]Graphic Contexts

In the X Window System core protocol, a graphic context (GC) serves as a server-side resource that bundles the parameters governing how graphical operations, such as drawing lines, shapes, and text, are performed on drawables like windows or pixmaps.[1] Identified by a unique 32-bit GCONTEXT value (with the top three bits reserved as zero), a GC enables efficient reuse of rendering attributes by clients, minimizing data transmission over the network connection to the server.[1] The server caches these contexts, allowing drawing requests to reference the GC identifier rather than repeating full parameter sets, which optimizes performance in networked environments.[1] GCs are created via the CreateGC request, which binds the specified GC identifier to a new context associated with a given drawable, such as a window or pixmap.[20] This request requires a value-mask bitfield to indicate which attributes are being initialized and a corresponding value-list providing their initial settings; unspecified attributes receive default values, such as GXcopy for the function or 0 for the plane mask.[20] The GC's attributes must be compatible with the drawable's root window and visual depth, or the server generates a Match error.[20] Possible errors include Alloc (resource exhaustion), Drawable (invalid drawable), GContext (ID conflict), IDChoice (invalid ID choice), Value (invalid attribute value), and others depending on the specified components.[20] The attributes of a GC encompass a range of rendering controls, as detailed in the following table:| Attribute | Type/Options | Description |

|---|---|---|

| function | CARD8; one of {GXclear, GXand, GXandReverse, GXcopy, GXandInverted, GXnoop, GXxor, GXor, GXnor, GXequiv, GXinvert, GXorReverse, GXcopyInverted, GXorInverted, GXnand, GXset} | Specifies the bitwise raster operation applied to source and destination pixels during drawing (e.g., GXcopy overlays the source directly, while GXxor performs a bitwise XOR).[1] |

| plane-mask | CARD32 | A bit mask selecting which bit planes in the drawable are modified by the operation (default: all ones).[1] |

| foreground | CARD32 | Pixel value used as the source color for drawing operations.[1] |

| background | CARD32 | Pixel value used as the background color, such as for clearing areas or in certain fill modes.[1] |

| line-width | CARD16 | Width of lines in pixels (default: 0 for a one-pixel-wide line).[1] |

| line-style | CARD8; one of {LineSolid, LineOnOffDash, LineDoubleDash} | Pattern for rendering lines (e.g., LineOnOffDash alternates drawing and gaps based on a dash list).[1] |

| cap-style | CARD8; one of {CapNotLast, CapButt, CapRound, CapProjecting} | Shape at the ends of lines (e.g., CapRound uses a semicircular cap).[1] |

| join-style | CARD8; one of {JoinMiter, JoinRound, JoinBevel} | Style for connecting line segments (e.g., JoinMiter extends edges to a point).[1] |

| fill-style | CARD8; one of {FillSolid, FillTiled, FillStippled, FillOpaqueStippled} | Method for filling polygons or arcs (e.g., FillTiled repeats a pixmap pattern).[1] |

| fill-rule | CARD8; one of {EvenOddRule, WindingRule} | Algorithm for determining interior points in non-convex polygons (e.g., EvenOddRule counts boundary crossings).[1] |

| arc-mode | CARD8; one of {ArcChord, ArcPieSlice} | Closure style for arc fills (e.g., ArcChord connects endpoints with a straight line).[1] |

| tile | PIXMAP | Pixmap used for tiled fills, aligned relative to the drawable origin.[1] |

| stipple | PIXMAP | Pixmap defining a stipple pattern for sparse fills.[1] |

| tile-stipple-x-origin | INT16 | X offset for aligning the tile or stipple pixmap.[1] |

| tile-stipple-y-origin | INT16 | Y offset for aligning the tile or stipple pixmap.[1] |

| font | FONT | Identifier of the font resource for text rendering operations.[1] |

| subwindow-mode | CARD8; one of {IncludeInferiors, ClipByChildren} | Handling of child windows during drawing (e.g., ClipByChildren excludes areas behind inferiors).[1] |

| graphics-exposures | BOOL | Flag to generate GraphicsExposure events for partially obscured drawing (default: true).[1] |

| clip-x-origin | INT16 | X offset for the clipping region relative to the drawable.[1] |

| clip-y-origin | INT16 | Y offset for the clipping region relative to the drawable.[1] |

| clip-mask | PIXMAP or None | Bitmap pixmap defining the clipping mask (None for no mask).[1] |

| dash-offset | CARD16 | Starting point in the dash pattern for line styles.[1] |

| dashes | CARD8 | Length of the dash pattern list (actual pattern set separately via SetDashes request).[1] |

Fonts and Text Rendering

The X Window System core protocol manages fonts as arrays of glyphs without performing any character set translation or interpretation; clients specify indices into the glyph array directly, while fonts include metric data for inter-glyph and inter-line spacing.[5] To load a font, clients issue the OpenFont request, providing a font identifier (fid) of type FONT and a font name as a STRING8, typically formatted according to the X Logical Font Description (XLFD) convention, such as -adobe-courier-medium-r-normal--12----.[5][24] This request loads the specified font if necessary and associates it with the provided identifier, returning errors like Alloc or Name if the allocation fails or the font is unavailable.[5] Font properties and metrics are queried via the QueryFont request, which takes a FONT identifier and replies with a FONTINFO structure containing overall font characteristics, including the draw direction (typically left-to-right), minimum and maximum character bounds (min-bounds and max-bounds encompassing width, ascent, and descent across all glyphs), and font ascent and descent for line spacing.[5] The reply also includes a list of per-character metrics in CHARINFO structures for characters within the font's defined range (from min-char-or-bytes to max-char-or-bytes), detailing for each glyph the left-side-bearing (offset from character origin to ink start), right-side-bearing (offset from ink end to advance width), character width (advance to next origin), ascent (height above baseline), and descent (depth below baseline); ink metrics define the bounding box as a rectangle from [x + left-side-bearing, y - ascent] with width (right-side-bearing + left-side-bearing) and height (ascent + descent).[5] Additionally, the reply provides font properties as a list of FONTPROP pairs, such as predefined atoms for POINT_SIZE (in decipoints), WEIGHT (scale 0-1000), and RESOLUTION (in dpi).[5] Text rendering in the core protocol uses the PolyText8 and PolyText16 requests to draw strings within a drawable using a specified graphics context (GC), which supplies the current font and attributes like foreground color affecting the text.[5] These requests specify a starting position (x, y) relative to the drawable's origin, with the y-coordinate aligned to the text baseline, and a list of TEXTITEM structures; PolyText8 handles 8-bit character codes (BYTE), while PolyText16 uses 16-bit codes (CHAR2B) for two-byte encodings like JIS or ISO.[5] Rendering proceeds left-to-right by default, treating each glyph as a mask for a fill operation via the GC's function (e.g., rasterop like GXcopy) and plane-mask; each TEXTITEM includes a delta (INT16) to adjust the x-position before drawing the subsequent string and supports a font escape mechanism where a character code of 0xff (all ones bits) in the string indicates a font-shift function (e.g., to switch fonts mid-string).[5] Fonts are closed with the CloseFont request, which deletes the association between the FONT identifier and the loaded font; the server retains the font data until the last client reference (e.g., in a GC) is released or the connection closes, preventing premature unloading.[5] The core protocol supports only fixed bitmap fonts without scalable capabilities, limited to 8-bit or 16-bit encodings for glyph indexing, and provides no support for vertical text rendering.[5]Rendering and Colors

Colors

The X Window System core protocol supports several visual types for color representation, each defining how pixels map to colors on a display. These include TrueColor, where pixels directly encode fixed RGB values using bit masks for red, green, and blue components; DirectColor, similar to TrueColor but allowing dynamic colormap indexing for each color subfield; PseudoColor, where pixels index a colormap to retrieve independent RGB values that can be modified; GrayScale, similar to PseudoColor but using equal RGB values for grayscale shades with a modifiable colormap; StaticColor, like PseudoColor but with fixed, server-defined colormap entries that cannot be altered; and StaticGray, which uses equal RGB intensities for grayscale shades with a read-only colormap. RGB components are specified as 16-bit unsigned integer fractions ranging from 0 to 65535, representing the full intensity spectrum, with hardware mapping performed linearly as hw-intensity = protocol-intensity / (65536 / total-hw-intensities).[25] Colormaps serve as lookup tables for translating pixel values to RGB colors in indexed visual types like PseudoColor and DirectColor, with each entry containing red, green, and blue intensities indexed from 0 up to the number of colormap entries defined by the visual. The protocol provides a default colormap for each screen, initially installed on the root window. To create a new colormap, the CreateColormap request specifies a colormap ID, a window whose visual type determines the colormap's format, and an allocation policy: None for no initial color allocations, or All to allocate all entries as read-write if supported by the visual. This request generates errors such as Alloc if insufficient resources are available, or Match if the visual type mismatches the window's screen.[26][27] Color allocation in the protocol allows clients to request specific RGB values and receive the closest available match. The AllocColor request targets a colormap with desired 16-bit RGB fractions and returns a 32-bit pixel value for the allocated cell along with the exact RGB achieved, enabling read-only access to that color; it generates Alloc errors if no free cells remain. For modifying existing allocations, the StoreColors request updates multiple colormap entries by providing a list of pixel values paired with new 16-bit RGB triples, applicable only to writable cells and subject to Access errors if the colormap is not owned by the client. In graphic contexts, colors are referenced via pixel values for foreground and background attributes, drawing from the currently installed colormap.[28][29] Pixel values in the protocol are 32-bit CARD32 integers, with their interpretation depth-dependent on the visual: for example, in TrueColor visuals, pixels pack RGB bits according to red_mask, green_mask, and blue_mask fields, while in PseudoColor, they serve as direct indices into the colormap. The depth and format, including bits per pixel (typically 1, 4, 8, 16, 24, or 32) and scanline padding to multiples of 8, 16, or 32 bits, can be queried using the visual information associated with screens or windows. Actual pixel packing varies by hardware and is not fixed at 32 bits universally.[25][30] To manage active colormaps, the InstallColormap request activates a specified colormap as the current one for its associated screen, replacing the previous installation and generating Match errors if the colormap's visual mismatches the screen. Colormaps can be deallocated by freeing individual color cells with the FreeColors request, which specifies a plane-mask for multi-plane visuals and a list of pixel values to release, or by destroying the entire colormap resource when no longer referenced. This request permits partial freeing even in All-allocated colormaps, provided the client owns the allocations, and handles Value errors for invalid pixels.[31][32]Drawing Operations

The drawing operations in the X Window System core protocol enable the rendering of geometric primitives and image data onto drawables, such as windows or pixmaps, by specifying a graphics context (GC) that defines attributes like foreground and background colors, line styles, and clipping regions. These requests operate in a client-server model where the client sends the operation details, and the server performs the rendering without returning data unless an error occurs. All coordinates are specified in pixels relative to the drawable's origin at the upper-left corner, with an optional "Previous" coordinate mode allowing relative positioning to the prior point for efficiency in polyline and polygon operations.[19] Line drawing is handled by the PolyLine and PolySegment requests, which render straight lines using lists of integer coordinates. The PolyLine request draws connected lines between successive points defined as (x, y) pairs in INT16 format, forming a continuous path from the first to the last point, while PolySegment draws independent segments each defined by endpoints (x1, y1) to (x2, y2), without joining them. Both requests require a drawable ID, a GC ID, and a coordinate mode (Origin for absolute positioning or Previous for relative). The GC controls key attributes, including the line-width (a CARD16 value, defaulting to 0 for a single pixel), line-style (LineSolid for a solid line, LineOnOffDash for alternating on-off segments using a dash list, or LineDoubleDash for double lines with gaps), cap-style (e.g., CapNotLast for square ends except at the final vertex), and join-style (e.g., JoinMiter for extended corners). The server validates these parameters and raises errors such as Match (for GC-drawable incompatibility) or Value (for invalid coordinates) if issues arise.[19] Rectangles and polygons are drawn using PolyRectangle for outlines and FillPoly for filled areas, leveraging polyline mechanisms for efficiency. The PolyRectangle request outlines multiple rectangles, each specified by an upper-left corner (x, y: INT16) and dimensions (width, height: CARD16), rendering each as a closed five-point polyline without filling. In contrast, FillPoly fills a closed polygon defined by a list of vertices (x, y: INT16), supporting coordinate modes for absolute or relative points; the shape parameter optimizes server processing (Complex for general polygons, Nonconvex for efficiency on simple nonconvex shapes, or Convex for the fastest rendering on convex polygons). The GC's fill-style (e.g., FillSolid) and fill-rule determine the interior: EvenOdd uses the even-odd rule (filling regions with an odd number of boundary crossings), while Winding employs the nonzero winding rule (filling based on net boundary direction). Both requests clip output to the drawable's bounds and GC clip-mask, discarding any portions outside without generating errors.[19] Arcs, including circular and elliptical variants, are managed by PolyArc for outlines and FillArcs for filled sectors, with ellipses treated as special cases spanning a full 360 degrees. Each arc is defined within a rectangle by position (x, y: INT16), size (width, height: CARD16), and angular extents (angle1: INT16 starting from the 3 o'clock position, angle2: INT16 extent, both in degrees scaled by 64 for precision, with positive values counterclockwise). The PolyArc request draws the arc outlines using the GC's line-width and style, while FillArcs fills the regions with an arc-mode (ArcChord for straight-line closures or ArcPieSlice for radial lines to the center), applying the GC's fill-style and fill-rule. For a full ellipse, angle2 minus angle1 equals 23040 (360 × 64), rendering a closed oval shape. As with other operations, arcs are clipped to the drawable and GC boundaries, ensuring no out-of-bounds rendering occurs.[19] Image transfer is performed via the PutImage request, which copies pixel data from the client to a drawable at specified coordinates. Parameters include the drawable and GC IDs, image depth (CARD16, matching the drawable's depth), dimensions (width, height: CARD16), destination offset (dst-x, dst-y: INT16), and left-pad (CARD8 bits for alignment). The data is provided as a LISTofBYTE in one of three formats: XYBitmap (depth 1, single-bit planes), XYPixmap (multiple independent bitmaps per plane), or ZPixmap (packed pixels in server-native byte order). The GC's function (e.g., GXcopy), plane-mask, and clip attributes (clip-mask, clip-x-origin, clip-y-origin) control blending and bounding, with the server handling byte-order conversion if needed. Validation ensures format compatibility, raising Match or Value errors for mismatches, and all rendering is confined to the drawable's extent without overflow handling.[19]Events and Input Handling

Events

The X Window System core protocol defines events as messages sent from the server to clients to report input activity, window exposure, and configuration changes. These events enable clients to respond to user interactions and system updates in a distributed environment. All core events follow a standardized format to ensure consistent processing across clients.[1] Events are structured as fixed 32-byte records, beginning with an 8-bit type code ranging from 0 to 63 for core protocol events, where the most significant bit is set if the event was synthesized via a SendEvent request. This is followed by a 16-bit sequence number for request tracking, a 32-bit window identifier (XID), and additional fields such as a timestamp in milliseconds since server start, along with event-specific data like coordinates or rectangles. The synthetic flag distinguishes server-generated events from those artificially produced by clients, aiding in security and debugging.[1] Key input events include KeyPress and KeyRelease, which notify of keyboard activity with a keycode value from 0 to 255, indicating the physical key pressed or released, and include details like the event time and root window coordinates. Similarly, ButtonPress and ButtonRelease events report mouse button actions for buttons 1 through 5, providing the button number, press or release state, and position relative to the event window. MotionNotify events signal pointer movement, delivering the x and y coordinates within the window, the time of the motion, and whether it occurred inside or outside the window boundaries. For graphics updates, Expose events describe areas of a window that require redrawing due to uncovering, specifying a damage rectangle with x, y, width, and height fields. ConfigureNotify events inform clients of window geometry modifications, such as changes in position, size, border width, or stacking order, including the new values for x, y, width, height, and border width.[1] Event delivery occurs selectively based on the event mask set by the client on a window via the CreateWindow or ChangeWindowAttributes requests; for example, the ButtonPressMask enables receipt of ButtonPress and ButtonRelease events. Events propagate from the innermost affected window outward through ancestor windows that have the relevant mask set, or via focus and pointer windows for input events, ensuring efficient notification without flooding clients. InputOnly windows, which lack visual representation, can receive input events such as KeyPress and ButtonPress but do not generate graphics-related events like Expose. To optimize bandwidth, certain events are compressed: EnterNotify and LeaveNotify are suppressed if the pointer has not crossed a window boundary, and multiple MotionNotify events are coalesced into a single one if no intervening state changes occur. Grabs may alter delivery paths for exclusive input control.[1]Input Devices and Keyboards