Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

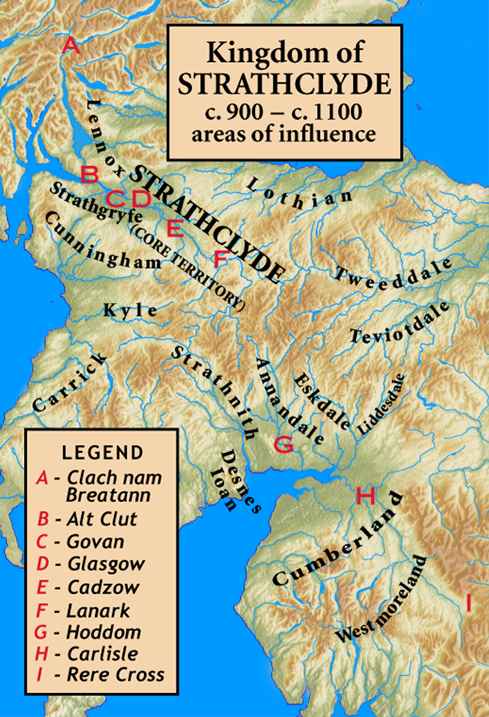

Kingdom of Strathclyde

View on Wikipedia

Strathclyde (Welsh: Ystrad Clud, "valley of the Clyde"), also known as Cumbria,[1] was a Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland and North West England, a region the Welsh tribes referred to as Yr Hen Ogledd (“the Old North"). At its greatest extent in the 10th century, it stretched from Loch Lomond to the River Eamont at Penrith.[1] Strathclyde seems to have been annexed by the Goidelic-speaking Kingdom of Alba in the 11th century, becoming part of the emerging Kingdom of Scotland.

Key Information

In its early days it was called the kingdom of Alt Clud, the Brittonic name of its capital, and it controlled the region around Dumbarton Rock.[2] This kingdom emerged during Britain's post-Roman period and may have been founded by the Damnonii people. After the sack of Dumbarton by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the capital seems to have moved to Govan and the kingdom became known as Strathclyde. It expanded south to the Cumbrian Mountains, into the former lands of Rheged. The neighbouring Anglo-Saxons called this enlarged kingdom Cumbraland.[1] We do not know what the inhabitants called their polity, though it may have been referred to as “Cumbria.”[3]

The language of Strathclyde is known as Cumbric, which was closely related to Old Welsh. Its inhabitants were referred to as Cumbrians. There was some later settlement by Vikings or Norse–Gaels , although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some settlement by Anglo-Saxons from Northumbria. Owing to the series of language changes in the area, it is unclear whether any Gaelic settlement took place before the 11th century.

Origins

[edit]

Ptolemy's Geographia – a sailors' chart, not an ethnographical survey[4] – lists a number of tribes, or groups of tribes, in southern Scotland at around the time of the Roman invasion and the establishment of Roman Britain in the 1st century AD. As well as the Damnonii, Ptolemy lists the Otalini, whose capital appears to have been Traprain Law; to their west, the Selgovae in the Southern Uplands and, further west in Galloway, the Novantae. In addition, a group known as the Maeatae, probably in the area around Stirling, appear in later Roman records. The capital of the Damnonii is believed to have been at Carman, near Dumbarton, but around five miles inland from the River Clyde.

Although the northern frontier of Roman Britain was Hadrian's Wall for most of its history, the extent of Roman influence north of the Wall is obscure. Certainly, Roman forts existed north of the wall, and forts as far north as Cramond may have been in long-term occupation. Moreover, the formal frontier was three times moved further north. Twice it was advanced to the line of the Antonine Wall, at about the time when Hadrian's Wall was built and again under Septimius Severus, and once further north, beyond the river Tay, during Agricola's campaigns, although, each time, it was soon withdrawn. In addition to these contacts, Roman armies undertook punitive expeditions north of the frontiers. Northern natives also travelled south of the wall, to trade, to raid and to serve in the Roman army. Roman traders may have travelled north, and Roman subsidies, or bribes, were sent to useful tribes and leaders. The extent to which Roman Britain was romanised is debated, and if there are doubts about the areas under close Roman control, then there must be even more doubts over the degree to which the Damnonii were romanised.[5]

The final period of Roman Britain saw an apparent increase in attacks by land and sea, the raiders including the Picts, Scotti and the mysterious Attacotti whose origins are not certain.[6] These raids will have also targeted the tribes of southern Scotland. The supposed final withdrawal of Roman forces around 410 is unlikely to have been of military impact on the Damnonii, although the withdrawal of pay from the residual Wall garrison will have had a very considerable economic effect.

No historical source gives any firm information on the boundaries of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, but suggestions have been offered on the basis of place-names and topography. Near the north end of Loch Lomond, which can be reached by boat from the Clyde, lies Clach nam Breatann, the Rock of the Britains, which is thought to have gained its name as a marker at the northern limit of Alt Clut.[7] The Campsie Fells and the marshes between Loch Lomond and Stirling may have represented another boundary. To the south, the kingdom extended some distance up the strath of the Clyde, and along the coast probably extended south towards Ayr.[8]

History

[edit]The Old North

[edit]

The written sources available for the period are largely Irish and Welsh, and very few indeed are contemporary with the period between 400 and 600. Irish sources report events in the kingdom of Dumbarton only when they have an Irish link. Excepting the 6th-century jeremiad by Gildas and the poetry attributed to Taliesin and Aneirin—in particular y Gododdin, thought to have been composed in Scotland in the 6th century—Welsh sources generally date from a much later period. Some are informed by the political attitudes prevalent in Wales in the 9th century and after. Bede, whose prejudice is apparent, rarely mentions Britons, and then usually in uncomplimentary terms.

Two kings are known from near contemporary sources in this early period. The first is Coroticus or Ceretic Guletic (Welsh: Ceredig), known as the recipient of a letter from Saint Patrick, and stated by a 7th-century biographer to have been king of the Height of the Clyde, Dumbarton Rock, placing him in the second half of the 5th century. From Patrick's letter it is clear that Ceretic was a Christian, and it is likely that the ruling class of the area were also Christians, at least in name. His descendant Rhydderch Hael is named in Adomnán's Life of Saint Columba. Rhydderch was a contemporary of Áedán mac Gabráin of Dál Riata and Urien of Rheged, to whom he is linked by various traditions and tales, and also of Æthelfrith of Bernicia.

The Christianisation of southern Scotland, if Patrick's letter to Coroticus was indeed to a king in Strathclyde, had therefore made considerable progress when the first historical sources appear. Further south, at Whithorn, a Christian inscription is known from the second half of the 5th century, perhaps commemorating a new church. How this came about is unknown. Unlike Columba, Kentigern (Welsh: Cyndeyrn Garthwys), the supposed apostle to the Britons of the Clyde, is a shadowy figure and Jocelyn of Furness's 12th century Life is late and of doubtful authenticity though Jackson[9] believed that Jocelyn's version might have been based on an earlier Cumbric-language original.

The Kingdom of Alt Clut

[edit]

After 600, information on the Britons of Alt Clut becomes slightly more common in the sources. However, historians have disagreed as to how these should be interpreted. Broadly speaking, they have tended to produce theories which place their subject at the centre of the history of north Britain in the Early Historic period. The result is a series of narratives which cannot be reconciled.[10] More recent historiography may have gone some way to addressing this problem.

At the beginning of the 7th century, Áedán mac Gabráin may have been the most powerful king in northern Britain, and Dál Riata was at its height. Áedán's byname in later Welsh poetry, Aeddan Fradawg (Áedán the Treacherous) does not speak to a favourable reputation among the Britons of Alt Clut, and it may be that he seized control of Alt Clut. Áedán's dominance came to an end around 604, when his army, including Irish kings and Bernician exiles, was defeated by Æthelfrith at the Battle of Degsastan.

It is supposed, on rather weak evidence, that Æthelfrith, his successor Edwin and Bernician and Northumbrian kings after them expanded into southern Scotland. Such evidence as there is, such as the conquest of Elmet, the wars in north Wales and with Mercia, would argue for a more southerly focus of Northumbrian activity in the first half of the 7th century. The report in the Annals of Ulster for 638, "the battle of Glenn Muiresan and the besieging of Eten" (Eidyn, later Edinburgh), has been taken to represent the capture of Eidyn by the Northumbrian king Oswald, son of Æthelfrith, but the Annals mention neither capture, nor Northumbrians, so this is rather a tenuous identification.[11]

In 642, the Annals of Ulster report that the Britons of Alt Clut led by Eugein son of Beli defeated the men of Dál Riata and killed Domnall Brecc, grandson of Áedán, at Strathcarron, and this victory is also recorded in an addition to Y Gododdin. The site of this battle lies in the area known in later Welsh sources as Bannawg—the name Bannockburn is presumed to be related—which is thought to have meant the very extensive marshes and bogs between Loch Lomond and the river Forth, and the hills and lochs to the north, which separated the lands of the Britons from those of Dál Riata and the Picts, and this land was not worth fighting over. However, the lands to the south and east of this waste were controlled by smaller, nameless British kingdoms. Powerful neighbouring kings, whether in Alt Clut, Dál Riata, Pictland or Bernicia, would have imposed tribute on these petty kings, and wars for the overlordship of this area seem to have been regular events in the 6th to 8th centuries.

There are few definite reports of Alt Clut in the remainder of the 7th century, although it is possible that the Irish annals contain entries which may be related to Alt Clut. In the last quarter of the 7th century, a number of battles in Ireland, largely in areas along the Irish Sea coast, are reported where Britons take part. It is usually assumed that these Britons are mercenaries, or exiles dispossessed by some Anglo-Saxon conquest in northern Britain. However, it may be that these represent campaigns by kings of Alt Clut, whose kingdom was certainly part of the region linked by the Irish Sea. All of Alt Clut's neighbours, Northumbria, Pictland and Dál Riata, are known to have sent armies to Ireland on occasions.[12]

The Annals of Ulster in the early 8th century report two battles between Alt Clut and Dál Riata, at "Lorg Ecclet" (unknown) in 711, and at "the rock called Minuirc" in 717. Whether their appearance in the record has any significance or whether it is just happenstance is unclear. Later in the 8th century, it appears that the Pictish king Óengus made at least three campaigns against Alt Clut, none successful. In 744 the Picts acted alone, and in 750 Óengus may have cooperated with Eadberht of Northumbria in a campaign in which Talorgan, brother of Óengus, was killed in a heavy Pictish defeat at the hands of Teudebur of Alt Clut, perhaps at Mugdock, near Milngavie. Eadberht is said to have taken the plain of Kyle in 750, around modern Ayr, presumably from Alt Clut.

Teudebur died around 752, and it was probably his son Dumnagual who faced a joint effort by Óengus and Eadberht in 756. The Picts and Northumbrians laid siege to Dumbarton Rock, and extracted a submission from Dumnagual. It is doubtful whether the agreement, whatever it may have been, was kept, for Eadberht's army was all but wiped out—whether by their supposed allies or by recent enemies is unclear—on its way back to Northumbria.

After this, little is heard of Alt Clut or its kings until the 9th century. The "burning", the usual term for capture, of Alt Clut is reported in 780, although by whom and in what circumstances is not known. Thereafter Dunblane was burned by the men of Alt Clut in 849, perhaps in the reign of Artgal.

The Viking Age

[edit]

An army, led by the Viking chiefs known in Irish as Amlaíb Conung and Ímar, laid siege in 870 to Alt Clut, a siege which lasted some four months and led to the destruction of the citadel and the taking of a very large number of captives. The siege and capture are reported by Welsh and Irish sources, and the Annals of Ulster say that in 871, after overwintering on the Clyde:

Amlaíb and Ímar returned to Áth Cliath (Dublin) from Alba with two hundred ships, bringing away with them in captivity to Ireland a great prey of Angles and Britons and Picts.

King Arthgal ap Dyfnwal, called "king of the Britons of Strathclyde", was killed in Dublin in 872 at the instigation of Causantín mac Cináeda.[13] He was followed by his son Run of Alt Clut, who was married to Causantín's sister. Eochaid, the result of this marriage, may have been king of Strathclyde, or of the kingdom of Alba.

From this time forward, and perhaps from much earlier, the kingdom of Strathclyde was subject to periodic domination by the kings of Alba. However, the earlier idea, that the heirs to the Scots throne ruled Strathclyde, or Cumbria as an appanage, has relatively little support, and the degree of Scots control should not be overstated. This period probably saw a degree of Norse, or Norse-Gael settlement in Strathclyde. A number of place-names, in particular a cluster on the coast facing the Cumbraes, and monuments such as the hogback graves at Govan, are some of the remains of these newcomers.

In the late ninth century the Vikings almost conquered England, apart from the southern kingdom of Wessex, but in the 910s the West Saxon king Edward the Elder and his sister Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, recovered England south of the Humber. According to the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, Æthelflæd formed an alliance with Strathclyde and Scotland against the Vikings, and in the view of the historian Tim Clarkson Strathclyde seems to have made substantial territorial gains at this time, some at the expense of the Norse Vikings. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that in 920 the kings of Britain, including the king of Strathclyde (who is not named), submitted to Edward. However, historians are sceptical of the claim as Edward's power was confined to southern Britain, and they think it was probably a peace settlement which did not involve submission. The names of Strathclyde's rulers in this period are uncertain, but Dyfnwal is thought to have been king in the early tenth century, and he was probably succeeded by his son Owain before 920.[14]

In 927 Edward's son Æthelstan conquered Viking-ruled Northumbria, and thus became the first king of England. At Eamont Bridge on 27 July several kings accepted his overlordship, including Constantine of Scotland. Sources differ on whether the meeting was attended by Owain of Strathclyde or Owain ap Hywel of Gwent, but it could have been both. In 934 Æthelstan invaded Scotland and laid waste to the country. Owain was an ally of the Scottish king and it is likely that Strathclyde was also ravaged. Owain attested Æthelstan's charters as sub-king in 931 and 935 (charters S 413, 434 and 1792), but in 937 he joined Constantine and the Vikings in invading England. The result was an overwhelming victory for the English at the Battle of Brunanburh.[15]

Following the battle of Brunanburh, Owain's son Dyfnwal ab Owain became king of Strathclyde. It is likely that whereas Scotland allied with England, Strathclyde held to its alliance with the Vikings. In 945, Æthelstan's half-brother Edmund, who had succeeded to the English throne in 939, ravaged Strathclyde. According to the thirteenth-century chronicler Roger of Wendover, Edmund had two sons of Dyfnwal blinded, perhaps to deprive their father of throneworthy heirs. Edmund then gave the kingdom to King Malcolm I of Scotland in return for a pledge to defend it on land and on sea, but Dyfnwal soon recovered his kingdom. He died on pilgrimage to Rome in 975.[16]

The end of Strathclyde

[edit]If the kings of Alba imagined, as John of Fordun did, that they were rulers of Strathclyde, the death of Cuilén mac Iduilb and his brother Eochaid at the hands of Rhydderch ap Dyfnwal in 971, said to be in revenge for the rape or abduction of his daughter, shows otherwise. A major source for confusion comes from the name of Rhydderch's successor, Máel Coluim, now thought to be a son of the Dyfnwal ab Owain who died in Rome, but long confused with the later king of Scots Máel Coluim mac Cináeda.[17] Máel Coluim appears to have been followed by Owen the Bald who is thought to have died at the battle of Carham in 1018. It seems likely that Owen had a successor, although his name is unknown.

Some time after 1018 and before 1054, the kingdom of Strathclyde appears to have been conquered by the Scots, most probably during the reign of Máel Coluim mac Cináeda who died in 1034.[18] In 1054, the English king Edward the Confessor dispatched Earl Siward of Northumbria against the Scots, ruled by Mac Bethad mac Findláich (Macbeth), along with an otherwise unknown "Malcolm son of the king of the Cumbrians", in Strathclyde. The name Malcolm or Máel Coluim again caused confusion, some historians later supposing that this was the later king of Scots Máel Coluim mac Donnchada (Máel Coluim Cenn Mór). It is not known if Malcolm/Máel Coluim ever became "king of the Cumbrians", or, if so, for how long.[19]

The Keswick area was conquered by the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria in the 7th century, but Northumbria was destroyed by the Vikings in the late 9th. In the early 10th century it became part of Strathclyde; it remained part of Strathclyde until about 1050, when Siward, Earl of Northumbria, conquered that part of Cumbria.[20]

Carlisle was part of Scotland by 1066, and thus was not recorded in the 1086 Domesday Book. This changed in 1092, when William the Conqueror's son William Rufus invaded the region and incorporated Cumberland into England. The construction of Carlisle Castle began in 1093 on the site of the Roman fort, south of the River Eden. The castle was rebuilt in stone in 1112, with a keep and the city walls.

By the 1070s, if not earlier in the reign of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, it appears that the Scots again controlled Strathclyde. It is certain that Strathclyde did indeed become an appanage, for it was granted by Alexander I to his brother David, Prince of the Cumbrians, later David I, in 1107.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Koch, John T (2012). The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. Bloomsbury. pp. 808–809.

- ^ Clarkson, Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons, p. 27

- ^ Edmonds, F. (2014). "The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria". The Scottish Historical Review, 93(237), p195-216

- ^ The description is Ó Corráin's, in R. Foster (ed.), The Oxford History of Ireland, p. 4.

- ^ For a brief survey of Rome and southern Scotland see Hanson, "Roman occupation".

- ^ The home of the Attacotti has been variously identified. Ireland is the most favoured location, and an association with the Déisi is plausible. A few authors have suggested the Outer Hebrides or the Northern Isles.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2011). Vanished Kingdoms. Penguin. p. 63. ISBN 9781846143380.

- ^ Alcock & Alcock, "Excavations at Alt Clut"; Koch, "The Place of Y Gododdin". Barrell, Medieval Scotland, p. 44, supposes that the diocese of Glasgow established by David I in 1128 may have corresponded with the late kingdom of Strathclyde.

- ^ Jackson, K.H. (1956) Language and History in Early Britain, Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press

- ^ Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men represents a work where the Britons are given prominence, but others have concentrated on Dál Riata. At present, the division appears to be between Scots, Irish and "north British" scholars and Anglo-Saxonists. Leslie Alcock, Kings and Warriors, could be taken as representing a "north British (and Irish)" perspective.

- ^ The Annals of the Four Masters associate Domnall Brecc of Dál Riata with these events.

- ^ The Northumbrians in 684, the Picts in the 730s and the Dál Riata on many occasions.

- ^ Edmonds, F (2015). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Strathclyde". Early Medieval Europe. 23 (1): 60. doi:10.1111/emed.12087. eISSN 1468-0254. S2CID 162103346.

- ^ Clarkson 2014, pp. 59–62; Davidson 2001, pp. 200–09.

- ^ Clarkson 2014, pp. 76–77, 80–84; Keynes 2002, Table XXXVI.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 359; Clarkson 2014, pp. 109, 125.

- ^ Duncan, Kingship of the Scots, pp. 23–24.

- ^ No King of Strathclyde is named by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle when Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, Mac Bethad and Echmarcach mac Ragnaill met with Canute in 1031.

- ^ For this episode see Duncan, Kingship of the Scots, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Charles-Edwards, pp. 12, 575; Clarkson, pp. 12, 63–66, 154–58

Sources

[edit]- Alcock, Leslie, Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2003. ISBN 0-903903-24-5

- Barrell, A.D.M., Medieval Scotland. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000. ISBN 0-521-58602-X

- Clarkson, Tim (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906566-78-4.

- Davidson, Michael (2001). "The (Non) Submission of the Northern Kings in 920". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 200–11. ISBN 978-0-415-21497-1.

- Duncan, A.A.M., The Kingship of the Scots 842–1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2002. ISBN 0-7486-1626-8

- Hanson, W.S., "Northern England and southern Scotland: Roman Occupation" in Michael Lynch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford UP, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-19-211696-7

- Keynes, Simon (2002). An Atlas of Attestations in Anglo-Saxon Charters, c.670–1066. Cambridge, UK: Dept. of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic, University of Cambridge, UK. ISBN 978-0-9532697-6-1.

- Koch, John, "The Place of 'Y Gododdin' in the History of Scotland" in Ronald Black, William Gillies and Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh (eds) Celtic Connections. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Celtic Studies, Volume One. Tuckwell, East Linton, 1999. ISBN 1-898410-77-1

- Smyth, Alfred P (1984). Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-6305-6.

- Stenton, Frank (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Barrow, G.W.S., Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, (corrected edn) 1989. ISBN 0-7486-0104-X

- Broun, D. (2004). "The Welsh Identity of the Kingdom of Strathclyde c. 900–c. 1200". Innes Review. 55 (55): 111–80. doi:10.3366/inr.2004.55.2.111.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clarkson, Tim (2010). The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906566-18-0.

- Driscoll, Stephen (2013). In Search of the Northern Britons in the Early Historic Era (AD 400–1100) (PDF). Culture and Sport Glasgow (Glasgow Museums).

- Edmonds, Fiona (October 2014). "The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria". The Scottish Historical Review. XCIII, 2 (237): 195–216. doi:10.3366/shr.2014.0216.

- Edmonds, Fiona (2015). "The expansion of the kingdom of Strathclyde". Early Medieval Europe. 23: 43–66. doi:10.1111/emed.12087. S2CID 162103346.

- Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2nd edn, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- Higham, N.J., The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100. Sutton, Stroud, 1993. ISBN 0-86299-730-5

- Jackson, Kenneth H., "The Britons in southern Scotland" in Antiquity, vol. 29 (1955), pp. 77–88. ISSN 0003-598X .

- Lowe, Chris, Angels, Fools and Tyrants: Britons and Anglo-Saxons in Southern Scotland. Canongate, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-86241-875-5

- Woolf, Alex (2001). "Britons and Angles". In Lynch, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199234820.

External links

[edit]- The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

- The Rolls edition of the Brut y Tywyssogion Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (pdf) at Stanford University Library

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork including the Annals of Ulster, the Annals of Tigernach and the Chronicon Scotorum.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, manuscripts D and E, various editions including an XML version by Tony Jebson.

- Google Books includes the Chronicon ex chronicis attributed to Florence of Worcester and James Aikman's translation (The History of Scotland) of George Buchanan's Rerum Scoticarum Historia

Kingdom of Strathclyde

View on GrokipediaGeography and Territory

Territorial Extent and Borders

The Kingdom of Strathclyde, initially known as Alt Clut, maintained its core territory in the strath of the River Clyde, extending from the river's estuary near Dumbarton upstream through the fertile valley encompassing modern areas around Glasgow and Paisley. This central region, vital for agriculture and defense, formed the kingdom's heartland from its formation in the post-Roman period through the early medieval era.[4] The capital at Dumbarton Rock provided a strategic stronghold overlooking the Clyde, facilitating control over maritime and riverine trade routes.[3] Northern borders in the kingdom's early phases likely reached as far as the vicinity of Clach nam Breatann, a standing stone near Loch Earn interpreted as a marker of Brittonic influence's limit against Pictish territories. This boundary, evident in archaeological and toponymic evidence, reflected defensive alignments against northern incursions, with fluctuations tied to military successes under kings like Riderch Hael in the late 6th century. Eastern limits abutted Gaelic Dál Riata and later Pictish expansions, while western coastal areas included islands like Bute and Arran under intermittent control.[5] Southern extents varied significantly due to conflicts with Northumbrian Angles and internal consolidations, initially aligning roughly with Hadrian's Wall before expansions southward into Cumbria. By the 10th century, under rulers like Dyfnwal ab Owain, the kingdom incorporated territories to the Solway Firth and beyond Carlisle, integrating diverse linguistic groups including Cumbric speakers. These gains, documented in annals and charters, peaked around 940 AD, encompassing much of modern Dumfries and Galloway and parts of northwest England, before Viking raids and Scottish integration eroded peripheral holdings.[3][2][6] The kingdom's borders thus represented a dynamic frontier shaped by topography, with the Clyde's natural barriers aiding cohesion, yet subject to contraction after the 870 Viking destruction of Dumbarton, shifting focus to Govan and southern outposts. Archaeological distributions, such as Govan School sculptures, corroborate post-Viking territorial continuity into Cumbria until the 11th-century absorption into the Kingdom of Alba.[7][6]Key Settlements and Capitals

The Kingdom of Strathclyde, originally termed the Kingdom of Alt Clut, centered its political authority on Dumbarton Rock, known as Alt Clut or "Rock of the Clyde" in Brittonic, which functioned as the primary capital from the 5th century onward.[8][9] This volcanic plug fortress, strategically positioned at the confluence of the Rivers Clyde and Leven, provided a defensible stronghold overlooking vital maritime routes and supported the kingdom's control over the Clyde estuary.[8] Archaeological and historical records indicate continuous occupation since at least the early medieval period, with the site enduring sieges, including a notable Viking assault in 870 that involved four months of bombardment leading to its capitulation.[4] After the Viking sack of Dumbarton in 870, the kingdom's focus shifted upstream along the Clyde to Govan, which emerged as the new de facto capital and a major ecclesiastical center.[4] Govan's significance is attested by the Govan Stones, a collection of 9th- to 11th-century carved monuments including hogbacks and crosses, likely associated with royal burials and Christian worship in the Brittonic tradition.[10] This relocation reflected adaptive resilience, with Govan serving as a religious and administrative hub amid Norse threats, evidenced by its curved graveyard and proximity to royal estates at Partick.[11] Key settlements beyond the capitals clustered in the fertile strath of the River Clyde, facilitating trade, agriculture, and defense, though specific urban centers were limited in this agrarian society. Sites such as Partick hosted royal demesnes, supporting the kingdom's economic base through proximity to arable lands and river access.[12] The northern boundary, marked by the Clach nam Breatann monolith near Balquhidder, signified fluctuating territorial influence rather than a fortified settlement.[4] These locations underscore Strathclyde's reliance on riverine geography for cohesion and survival until its integration into broader Scottish realms by the 11th century.[9]Origins

Pre-Roman and Roman Context

The region encompassing the later Kingdom of Strathclyde, centered on the Clyde Valley in southern Scotland, was inhabited during the Iron Age by Brittonic-speaking Celtic peoples who constructed defended settlements such as hill forts.[4] Archaeological evidence indicates occupation from at least the late Bronze Age transitioning into the Iron Age around 800 BCE, with sites featuring ramparts, ditches, and timber structures typical of Atlantic roundhouse cultures. The Dumbarton Rock, a prominent volcanic plug overlooking the Clyde, served as an early fortified site, exemplifying the defensive architecture used by local communities before Roman contact.[13] The specific tribal group in the Clyde Valley was the Damnonii, a Brittonic people whose territory extended across much of what became Strathclyde, as recorded in Ptolemy's Geography circa 150 CE based on earlier Roman surveys.[4] The name Damnonii may derive from a term implying dominance or mastery, reflecting their control over fertile straths and riverine resources.[14] These groups engaged in agriculture, pastoralism, and trade, with evidence of ironworking and contact with southern British tribes, but maintained distinct cultural practices without centralized kingdoms.[15] Roman incursions began around AD 71 under Governor Agricola, who conducted campaigns northward, achieving temporary submissions from northern tribes including those in the Clyde area by AD 83.[15] However, full conquest was not achieved; Agricola's advance relied on short-term forts and legions rather than permanent infrastructure, and withdrawals followed due to logistical challenges and resistance.[16] In AD 142, Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered the construction of the Antonine Wall from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde, incorporating parts of Damnonii territory into a frontier zone with turf-and-stone fortifications and signal stations, held until abandonment around AD 160-165.[15] Roman influence in the core Strathclyde region remained superficial, with sporadic military patrols and trade items like pottery and coins found in native sites, but no evidence of widespread Romanization or displacement of the Damnonii, who retained autonomy beyond the wall's effective control.[17] By the late 2nd century, Roman forces retracted to Hadrian's Wall, leaving the area to revert to pre-existing Brittonic polities.[15]Post-Roman Formation

The Kingdom of Strathclyde, initially known as Alt Clut, formed in the power vacuum following the Roman legions' withdrawal from Britain around 410 AD, as local Brittonic elites consolidated authority in the Clyde valley region previously associated with the Damnonii tribe.[4] [18] The Damnonii, a Iron Age Celtic people documented by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD, occupied territories north of the Antonine Wall, experiencing only intermittent Roman military incursions rather than sustained provincial administration.[4] [19] This limited Roman overlay allowed for greater cultural and political continuity into the post-Roman era compared to southern Britain.[20] Archaeological continuity from La Tène Iron Age settlements underscores the Britons' persistence in southern Scotland, with the post-Roman kingdom emerging as a polity centered on fortified sites like Dumbarton Rock, or Alt Clut ("Rock of the Clyde"), a defensible volcanic basalt outcrop overlooking the River Clyde.[18] [21] The kingdom's formation likely stemmed from the reorganization of sub-Roman tribal structures under warlord-like rulers who leveraged existing hillforts and riverine defenses against emerging threats from Picts to the north and Germanic settlers to the south.[5] Early textual evidence is scarce, with no contemporary records; the polity's existence is inferred from later king lists and place-name survivals indicating Brittonic dominance in the region through the 5th and 6th centuries.[4] By the mid-6th century, Alt Clut had established itself as one of several successor states to Roman Britain in the north, maintaining a distinct Cumbric (Brittonic) identity amid the fragmentation of central authority.[18] The kingdom's territorial core encompassed the strath of the Clyde from Dumbarton eastward, with probable early extensions marked by sites like Clach nam Breatann, though boundaries fluctuated due to raids and alliances.[4] This phase reflects causal dynamics of local adaptation to imperial collapse, where geographic barriers like the Clyde fostered resilience against lowland Anglo-Saxon expansion.[19]Political and Dynastic History

Early Kings and the Kingdom of Alt Clut

The Kingdom of Alt Clut represented the initial phase of the Brittonic realm later known as Strathclyde, with its core territory encompassing the Clyde River valley and centered on the imposing volcanic rock fortress of Dumbarton, referred to in Brittonic as Alt Clut ("rock of the Clyde"). This stronghold, strategically positioned overlooking the River Clyde, served as the primary seat of royal power from at least the 5th century, providing natural defenses against incursions from Picts to the north and Northumbrians to the southeast.[4] The kingdom's inhabitants were Britons speaking a Cumbric language, descending from the pre-Roman Damnonii tribe, and maintained continuity with Roman-era provincial structures in the absence of full conquest by Rome.[4] The earliest historically attested king is Ceretic Guletic, who ruled in the late 5th century and is widely identified with Coroticus, the recipient of St. Patrick's Epistle to Coroticus, a primary document denouncing him for leading raids into Ireland that captured and enslaved newly baptized Christians.[22] Patrick, writing as a bishop in Ireland around 480, excommunicated Coroticus and his soldiers, highlighting tensions between Brittonic rulers and Irish missionary efforts, as well as the practice of slave-trading across the Irish Sea.[23] Ceretic's reign marks the first named evidence of organized kingship in Alt Clut, though the kingdom's formation likely predated him amid the power vacuum following Roman withdrawal circa 410.[20] Succeeding rulers are known primarily through later medieval genealogies and saintly vitae, which blend historical and legendary elements, with sparse contemporary records until the 7th century Irish annals. Ceretic's son or close kin, Dumnagual Hen ("the Elder"), is listed in royal pedigrees as an early 6th-century king, possibly extending influence into Galloway and the Gododdin region through familial alliances or conquests.[4] By mid-century, Riderch Hael ("the Generous"), son of Tutagual, emerged as a prominent figure, reigning approximately 573–614 and hosting the exiled bishop Kentigern (Mungo) at his court near Dumbarton, fostering Christian consolidation amid regional warfare.[4] Riderch's involvement in the Battle of Arfderydd (573), recorded in Annales Cambriae, underscores Alt Clut's role in inter-Brittonic conflicts, potentially against allies of the northern Picts.[4] From the 7th century, Irish annals provide firmer chronological anchors for Alt Clut's kings, reflecting growing interactions with Gaelic Scotland and Northumbria. Guret, king of Alt Clut, is noted in the Annals of Ulster around 642, followed by Domnall mac Auin, whose death is recorded in the Annals of Tigernach circa the same period, indicating a sequence of short reigns amid external pressures.[24] These rulers navigated alliances and hostilities, including Pictish campaigns under Óengus mac Fergusa in the 8th century, which failed to subjugate Alt Clut despite sieges and raids.[4] The kingdom's resilience stemmed from its defensible geography and maritime connections, preserving Brittonic autonomy until the devastating Viking assault on Dumbarton in 870–871, after which the royal focus shifted southward along the Clyde.[4]Viking Age Disruptions and Recovery

The Viking Age posed severe threats to the Kingdom of Alt Clut, with Norse-Gael forces from Dublin launching a prolonged siege against Dumbarton Rock, the kingdom's principal stronghold, in 870. Led by the Viking leaders Olaf (Amlaíb) and Ivar (Ímar), the attackers blockaded the rock for four months, exploiting its isolation and limited water supply until the defenders capitulated.[8] This assault resulted in the sacking of Alt Clut, with contemporary accounts noting the enslavement of numerous Britons who were transported to Dublin's markets, severely depleting the kingdom's population and resources.[25] The fall of Dumbarton marked a critical disruption, as the fortress had served as the political and symbolic heart of the realm since at least the 6th century, undermining Alt Clut's maritime defenses and exposing surrounding territories to further incursions.[8] Despite the devastation, the kingdom did not collapse entirely, demonstrating resilience through dynastic continuity and territorial adaptation. Surviving elites likely relocated southward along the Clyde Valley, with Govan emerging as a new ecclesiastical and possibly royal center by the late 9th century, evidenced by high-status sculptures and burial monuments dating from this period.[26] The realm's name shifted to reflect its broader "Strathclyde" extent, incorporating valleys beyond the immediate Clyde strath, and records indicate ongoing royal activity, such as the death of Run, son of Arthur and a king of Alt Clut, in 878, suggesting immediate post-siege leadership persisted amid Norse threats.[27] Recovery gained momentum in the 10th century under kings like Owain (ruled c. 890s–930s) and Dyfnwal ab Owain (ruled c. 930s–970s), who reasserted control over core territories and expanded influence into northern Cumbria, leveraging alliances with emerging Scottish powers in Alba to counter residual Viking pressures. Archaeological and charter evidence from sites like Govan Old Church, including hogback stones indicative of Norse stylistic influence yet tied to Brittonic patronage, highlights cultural hybridization without full subjugation.[26] By the mid-10th century, Strathclyde participated in regional coalitions, such as potential involvement in conflicts against York-based Vikings, restoring its status as a viable Brittonic polity until deeper integration with Alba in the 11th century.[1] This phase of reconfiguration underscores the kingdom's adaptive capacity, rooted in geographic advantages of the Clyde's navigable strath and persistent elite networks.Late Period and Integration with Alba

Following the Viking destruction of Dumbarton Rock in 870, the Kingdom of Strathclyde relocated its primary centers southward to the vicinity of Govan and Paisley, facilitating recovery and continuity into the 10th century.[28] Under rulers such as Dyfnwal (r. circa 908–926), the kingdom expanded its influence into northern Cumbria, incorporating Brittonic territories previously under Northumbrian control.[3] This period witnessed strategic alliances with the Kingdom of Alba, including joint opposition to English expansion, as seen in Owain's participation alongside Constantine II at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937.[29] In the early 11th century, kings like Máel Coluim (d. 997) and Owain Foel maintained Strathclyde's autonomy while increasingly aligning with Alba against Northumbrian threats.[30] Owain Foel, the last attested independent ruler, fought at the Battle of Carham in 1018, where allied Strathclyde and Scottish forces under Malcolm II decisively defeated the Northumbrians, securing Lothian for Alba.[31] This victory underscored Strathclyde's military value but also accelerated its subordination, as no subsequent kings are recorded independently.[32] Integration into Alba occurred gradually during the 11th century, likely formalized under Malcolm II (r. 1005–1034) following Owain Foel's death, possibly in 1018 or shortly thereafter.[33] By the mid-11th century, Strathclyde's territories were administered directly by Scottish kings, with Govan serving as a key ecclesiastical and symbolic site until its eclipse by emerging Gaelic dominance.[34] The process reflected Alba's expansionist policies, absorbing Brittonic institutions without abrupt conquest, though Brittonic linguistic and cultural elements persisted locally into later centuries.[32]Society, Economy, and Culture

Social Structure and Governance

The Kingdom of Strathclyde operated under a monarchical system, with the king functioning as the primary political, military, and judicial authority, a structure inherited from its tribal roots among the Damnonii and consolidated in the post-Roman era around the fortress of Alt Clut (Dumbarton Rock).[4] [20] Kings such as Ceretic (c. 5th century) and later rulers like Dyfnwal maintained control through personal loyalty networks, including retainers and allied warlords who administered territories and enforced royal will.[20] No evidence survives of formalized bureaucratic institutions, assemblies, or written laws; governance appears to have relied on customary practices, oaths of fealty, and ad hoc councils of nobles during crises, such as Viking incursions or dynastic challenges.[4] Dynastic succession predominated, often favoring sons or brothers, as seen in the transition from Ceretic to his son Dyfnwal and the latter's brother Tutgual, though competition from collateral lines occasionally led to instability, exemplified by the brief subjugation under Scottish kings like Eochaid in the late 9th century.[20] [4] The nobility comprised a warrior aristocracy tied to the royal house through blood, marriage, or service, providing military support in exchange for land rights and tribute extraction from lower strata; figures like Elidyr (c. 550s) illustrate intermarriages with other Brittonic elites, reinforcing alliances.[4] Social hierarchy mirrored broader early medieval Celtic patterns, with the king and nobles at the apex, followed by free landowners and tenant farmers who sustained the elite via agricultural renders and levies, while slaves—captured in raids or born into bondage—formed the base, though direct archaeological or textual evidence for Strathclyde remains scant.[4] Christianity, adopted by the 5th century as evidenced by St. Patrick's rebuke of King Coroticus for enslaving fellow Christians, gradually influenced social norms and royal legitimacy, integrating ecclesiastical figures into advisory roles without supplanting secular authority.[20] This structure persisted amid territorial flux, adapting to pressures from Picts, Northumbrians, and Vikings until integration into the Kingdom of Alba around 1034.[4]Economy and Trade

The economy of the Kingdom of Strathclyde relied primarily on agriculture and pastoralism, exploiting the fertile strath of the River Clyde for arable farming and livestock rearing. Excavations at Titwood in East Renfrewshire uncovered a palisaded farmstead dated to the 8th–10th centuries, indicative of organized crop cultivation in this period.[18] Similarly, evidence from Dolphinton in Lanarkshire points to livestock-focused activities alongside iron working across the 5th–10th centuries.[18] Maritime trade was central, with Dumbarton (Alt Clut) functioning as a key port from the 5th century onward, connected to broader Atlantic networks via the Clyde estuary. Archaeological finds there include imported B-ware and E-ware pottery alongside glass vessels, likely for wine, signaling early Mediterranean and continental imports.[18][1] High-status sites like Dundonald Castle yielded further imported pottery, glass, and metalworking debris, underscoring elite participation in exchange networks.[18] During the Viking Age, trade routes along the Clyde linked the Irish Sea province to the Western Isles and eastern coasts via portages such as Rutherglen-Blackness and the Biggar Gap.[35] Post-870 siege artifacts at Dumbarton, including lead weights and a sword guard, reflect ongoing Irish Sea commerce, while hoards like Port Glasgow's—containing silver arm-rings and coins—and stray finds such as an Arabic dirhem at Stevenston Sands indicate bullion-based exchange with Scandinavian and Islamic spheres.[35][18] Midross cemetery graves (late 9th–10th centuries) further attest to imported items like Norwegian whetstones and Anglo-Saxon coin fragments, highlighting multicultural economic integration.[35]Language, Identity, and Cultural Continuity

The primary language of the Kingdom of Strathclyde was Cumbric, a Brittonic Celtic tongue closely akin to Old Welsh and distinct from the Goidelic Gaelic spoken by Scots to the north or the Anglian dialects encroaching from the east.[36] Cumbric persisted as the vernacular from the post-Roman period through the early Middle Ages, with evidence drawn chiefly from toponymy across the Clyde valley and adjacent regions, such as elements denoting geographical features (e.g., caer for fort, penn for hill) in names like Penicuik or Cumwhitton, reflecting P-Celtic phonology.[37] Personal names in surviving charters and annals, including those of rulers like Owain (from Brittonic Eugeniau) and Dyfnwal, further attest to its use among the elite into the 10th century.[3] The Britons of Strathclyde maintained a robust ethnic identity rooted in their descent from Iron Age Damnonii tribes, viewing themselves as heirs to Romano-British traditions rather than kin to Gaelic Scots or Pictish groups.[1] This self-conception is evident in Irish annalistic references to their kings as ríg Brettan (kings of the Britons) and in the kingdom's core toponyms like Alt Clut ("Rock of the Clyde"), symbolizing continuity with pre-Anglo-Saxon Britain. Archaeological and sculptural evidence from sites like Govan, including hogback stones and sarcophagi with Brittonic motifs, reinforces this warrior-elite identity tied to Christianized British heritage, distinct from Norse or Gaelic overlays.[1] Cultural continuity endured despite external pressures, including the Viking devastation of Alt Clut in 870, as the kingdom reconstituted around new centers like Govan and retained Brittonic linguistic and artistic forms into the 11th century.[1] Early Christian monuments and heroic poetry akin to the Gododdin (preserving Brittonic verse traditions) highlight unbroken ties to the "Old North" (Hen Ogledd), with literacy in Latin alongside Cumbric facilitating ecclesiastical links to Wales and Cumbria.[1] Incorporation into the expanding Kingdom of Alba from the late 10th century introduced Gaelic administrative dominance, accelerating linguistic assimilation—evidenced by hybrid place names in Renfrewshire and Ayrshire—but Brittonic substrates lingered in rural toponymy and folklore well beyond 1100, underscoring resilient local adaptation over wholesale replacement.[37][1]Religion and Institutions

Conversion to Christianity

The Kingdom of Strathclyde, as a successor state to the Romanized Damnonii, likely experienced initial Christian influences in the 5th century through lingering Roman provincial practices and maritime trade networks along the Clyde.[1] A potential early indicator is the 5th-century ruler Coroticus, possibly of Alt Clut (Dumbarton), rebuked by St. Patrick for leading raids involving baptized Christians, implying partial adoption or nominal Christianity among the elite.[1] However, direct evidence remains sparse, with post-Roman disruptions contributing to localized pagan resurgence or syncretism amid tribal conflicts.[38] Christianization accelerated in the mid-6th century under St. Kentigern (also Mungo, d. c. 603–612), consecrated bishop around 543 and regarded as the primary missionary to the region.[38][39] Kentigern established a bishopric at Glasgow, founded monastic communities, ordained clergy, and preached extensively, extending his efforts into adjacent areas like Cumbria.[39] His ministry received royal patronage from King Rhydderch Hael (r. c. 580–614), a baptized Christian monarch who supported ecclesiastical expansion and is credited with defending the faith against pagan elements.[39][40] A temporary anti-Christian reaction around 553 compelled Kentigern's exile to Wales, but his return followed Rhydderch's military successes, including the Battle of Arderydd in 573, where Brittonic forces confronted pagan rivals, bolstering Christian ascendancy.[38] Accounts of Kentigern's conversions emphasize both preaching and attributed miracles, though primary sources—such as Jocelyn of Furness's 12th-century Life of Kentigern—incorporate hagiographic legends derived from oral traditions, limiting their precision for causal reconstruction.[39] Archaeological corroboration includes 5th–6th-century Christian burials at sites like Govan Old Parish Church, alongside later sculptures indicating an enduring ecclesiastical role, though systematic evidence for early conversion sites remains underdeveloped pending further excavation.[1] By the late 6th century, Christianity had transitioned from elite adoption to institutional presence, evidenced by church dedications to Kentigern and integration with broader Insular networks, setting the stage for Strathclyde's medieval religious landscape.[38]Ecclesiastical Centers and Influence

The bishopric of Glasgow, founded by Saint Kentigern (also known as Mungo) around 560, served as the primary ecclesiastical center in early Strathclyde. Kentigern, consecrated bishop in 543 and active as a missionary across the region from the Clyde to the Mersey, established his main seat at Glasgow, repairing an earlier church attributed to Saint Ninian and building a monastic community there.[38] [41] He died in 603, leaving a legacy of evangelization that solidified Christianity among the Brittonic population, though hagiographic accounts exaggerate the scale of his foundations, such as claims of 965 monks.[38] [42] Following the Viking sack of Dumbarton Rock in 870, which disrupted earlier power structures, Govan in the Clyde Valley rose as the kingdom's premier religious and ceremonial site from the late 9th to mid-11th centuries. This shift aligned with the recovery of Strathclyde under kings like Donald mac Alpin, positioning Govan as a hub for royal patronage, high-status burials, and Christian rituals, including probable court masses on feast days like Christmas in 935.[43] Archaeological finds, including over 30 early medieval sculptured stones—such as cross-slabs, hogbacks, and memorials—attest to its prosperity and connections to elite Brittonic and possibly Scandinavian-influenced artistry, marking it as a focal point for ecclesiastical authority amid political fragmentation.[44] [45] Strathclyde's church operated within the Brittonic tradition, emphasizing missionary bishops and monastic communities rather than a rigid diocesan structure, with influences from Ninian's 5th-century mission at Whithorn in Galloway—sometimes under loose Strathclyde oversight but often independent.[38] By 704, it had conformed to Catholic usages, predating similar alignments in Welsh churches, though limited primary records hinder precise delineation of influence beyond local evangelization and ties to broader Celtic Christianity.[38] The see of Glasgow lapsed after Kentigern but revived in the 12th century within the emerging Scottish church framework.[38]Military Affairs and External Relations

Defensive Strategies and Key Conflicts

The Kingdom of Strathclyde's defensive strategies emphasized naturally defensible positions, particularly the volcanic basalt crags of Dumbarton Rock, known anciently as Alt Clut, which overlooked the River Clyde and provided a formidable stronghold accessible primarily by water.[8] This site, with its twin peaks separated by a ravine and surrounded by tidal waters, allowed defenders to withstand prolonged sieges by limiting landward approaches and enabling resupply via the river.[46] Control of the Clyde valley's straths further facilitated monitoring and blocking invasions along key waterways, while hillforts and later ecclesiastical sites like Govan offered secondary bastions for regional defense.[29] Strathclyde faced persistent threats from neighboring powers, including the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, which conquered southern territories such as the Keswick area in the seventh century through military expansion.[4] Pictish and Scottish incursions from Dál Riata pressured the northern frontiers, contributing to territorial fluctuations, though direct battles are sparsely recorded beyond broader regional conflicts.[4] The most devastating conflict was the Viking siege of Dumbarton Rock in 870, when Norse leaders Amlaíb (Olaf the White) of Dublin and Ímar (Ivar the Boneless) blockaded the fortress for four months, employing sustained assaults that culminated in its capture and subsequent plundering over several days.[46] [8] This event disrupted the kingdom's core, leading to a temporary Norse occupation and the relocation of royal centers southward to areas like Govan, though Brittonic recovery occurred by the early tenth century.[47] [29] In the tenth century, Strathclyde forces participated in the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, allying with Scots and Vikings against the English king Æthelstan, but suffered defeat in this coalition effort to challenge English dominance.[48] Later defensive actions included repelling a Northumbrian incursion at the Battle of Newburgh, where Strathclyde warriors under a king named Domnall destroyed the invading force shortly after an initial setback.[49] These engagements underscored Strathclyde's role in buffering against Anglo-Saxon and Norse pressures, often through opportunistic alliances rather than sustained offensive campaigns.Alliances and Diplomacy

The Kingdom of Strathclyde engaged in pragmatic diplomacy focused on countering threats from Anglo-Saxon expansion and Viking incursions, often through temporary alliances and submissions rather than enduring treaties. Early relations with neighboring Brittonic kingdoms emphasized mutual defense against Bernician incursions; for instance, King Rhiderch Hael (r. c. 573–612) joined a confederation with Rheged and Elmet around 590, besieging the Anglo-Saxon island monastery of Lindisfarne.[4] Interactions with the Gaelic Dál Riata kingdom oscillated between conflict, such as border skirmishes in 711 and 717 recorded in the Annals of Ulster, and later cooperation, including alliances like that formed by Rhun mac Arthgal (r. 872–878) with Constantine II of the Scots.[4] Hostility dominated relations with Northumbria, marked by territorial losses like the cession of the Kyle plain to King Eadberht in 750 and joint Pictish-Northumbrian assaults on Dumbarton in 756, which prompted a peace capitulation.[4] In the Viking Age, diplomacy with Anglo-Saxon England involved cycles of warfare interspersed with uneasy peaces and oaths of fealty, frequently disrupted by shifting power dynamics and Norse interventions; these relations are documented in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle alongside instances of temporary alignment against common foes.[50] A notable example of anti-English coalition-building occurred in 937, when King Owain allied Strathclyde forces with Constantine II of Scots and Olaf Guthfrithson of Dublin Norse against King Athelstan at the Battle of Brunanburh, a decisive English victory that underscored the fragility of such pan-northern alliances.[48] Diplomatic submissions followed; in 927, regional assemblies at Eamont involved Scottish acknowledgment of English overlordship, with Strathclyde implicated in the broader northern realignments, while in 945 King Dyfnwal ab Owain yielded to Edmund I after an invasion that included the blinding of two of Dyfnwal's sons, leading Edmund to grant Cumbrian territories to Malcolm I of Scots as a defensive buffer, though Strathclyde later reasserted partial independence.[50][6] These maneuvers, including occasional dynastic ties with Gaelic and Norse elites, facilitated survival until the kingdom's absorption into Alba around 1034.[4]Rulers and Succession

Known Kings and Dynasties

The rulers of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, initially centered on Alt Clut (Dumbarton Rock), are known primarily from sparse contemporary records in Irish annals, hagiographies, and later medieval genealogies, with chronology often approximate due to limited documentation. The earliest attested king is Ceretic Guletic, who flourished around 480 AD and is rebuked in a surviving letter from St. Patrick for enslaving baptized Irish captives, indicating early Christian influence among the Brittonic elite.[9] Later in the 6th century, Riderch Hael (Rhydderch the Generous), son of Tudwal, ruled from circa 573 to 612 and maintained alliances with Gaelic missionaries, as evidenced in Adomnán's Life of Columba, where he is portrayed as a powerful Christian monarch hosting the saint.[51] Obituary notices in the Annals of Ulster provide evidence for 7th- and 8th-century kings, reflecting ongoing political activity amid pressures from Picts, Scots, and Northumbrians. These include Guret (d. 658), Domnall son of Auin (d. 694), Einion (d. 722), Ciniod I (d. 750), and Dumnagual III (d. 760), among others, whose reigns suggest dynastic continuity despite intermittent conflicts.[52] The Viking destruction of Alt Clut in 870 marked a transition; the subsequent king, Arthgal (d. 872), was executed amid intrigue involving Scottish king Constantine I, after which his son Rhun ruled briefly until circa 878.[30] The Harleian Genealogies (British Library, Harley MS 3859), compiled in the 10th century, trace a single Brittonic dynasty from Ceretic through intermediate figures like Dumnagual Hen and Clinoch to Rhun son of Arthgal, underscoring hereditary succession within a patrilineal house despite evidential gaps.[53] Post-Viking recovery saw rulers such as Dyfnwal (fl. 908–943), who minted coinage and expanded influence, and Owain Foel (the Bald, d. after 1018), the last named king, who allied with Malcolm II of Scotland at the Battle of Carham.[30] No distinct secondary dynasties are attested; later integration into Scotland around 1070 ended independent rule, with sources like the Annals of Ulster ceasing specific references to Strathclyde kings thereafter.[4]| King | Approximate Reign/Death | Key Events/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Ceretic Guletic | fl. c. 480 | St. Patrick's letter; early Christian king.[9] |

| Riderch Hael | c. 573–612 | Alliance with Columba; Life of Columba.[51] |

| Guret | d. 658 | Annals of Ulster.[52] |

| Domnall m. Auin | d. 694 | Annals of Ulster.[52] |

| Einion | d. 722 | Annals of Ulster.[52] |

| Ciniod I | d. 750 | Annals of Ulster.[4] |

| Arthgal | d. 872 | Killed post-Viking siege; Annals of Ulster.[30] |

| Rhun m. Arthgal | c. 872–878 | Son of Arthgal; Harleian Genealogies.[53] |

| Owain Foel | fl. c. 1000–1018 | Battle of Carham; Annals of Ulster.[30] |