Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

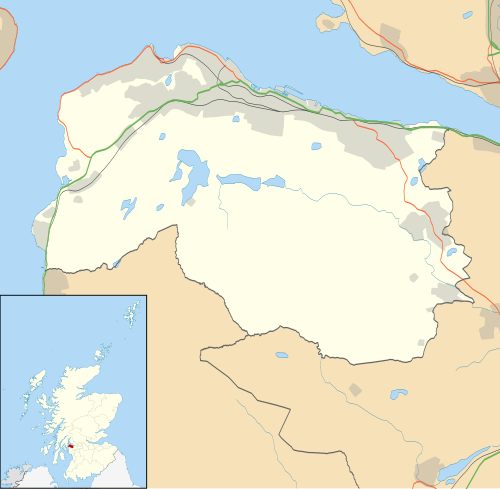

Inverclyde

View on Wikipedia

Inverclyde (Scots: Inerclyde, Scottish Gaelic: Inbhir Chluaidh, pronounced [iɲiɾʲˈxl̪ˠuəj], "mouth of the Clyde") is one of 32 council areas used for local government in Scotland. Together with the East Renfrewshire and Renfrewshire council areas, Inverclyde forms part of the historic county of Renfrewshire, which currently exists as a registration county and lieutenancy area. Inverclyde is located in the west central Lowlands. It borders the North Ayrshire and Renfrewshire council areas, and is otherwise surrounded by the Firth of Clyde.

Key Information

Inverclyde was formerly one of nineteen districts within Strathclyde Region, from 1975 until 1996. Prior to 1975, Inverclyde was governed as part of the local government county of Renfrewshire, comprising the burghs of Greenock, Port Glasgow and Gourock, and the former fifth district of the county. Its landward area is bordered by the Kelly, North and South Routen burns to the southwest (separating Wemyss Bay and Skelmorlie, North Ayrshire), part of the River Gryfe and the Finlaystone Burn to the south-east.

It is one of the smallest in terms of area (29th) and population (28th) out of the 32 Scottish unitary authorities. Along with the council areas clustered around Glasgow it is considered part of Greater Glasgow in some definitions,[3] although it is physically separated from the city area by open countryside and does not share a border with the city.

The name derives from the extinct barony of Inverclyde (1897) conferred upon Sir John Burns of Wemyss Bay and his heirs.

Council

[edit]History

[edit]Inverclyde was created as a district in 1975 under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973, which established a two-tier structure of local government across mainland Scotland comprising upper-tier regions and lower-tier districts. Inverclyde was one of nineteen districts created within the region of Strathclyde. The district covered the area of four former districts from the historic county of Renfrewshire, all of which were abolished at the same time:[4][5]

- Greenock Burgh

- Gourock Burgh

- Port Glasgow Burgh

- Fifth District, being the landward (outside a burgh) parts of the parishes of Greenock, Inverkip, Port Glasgow, and Kilmacolm.

The new district was named Inverclyde, meaning "mouth of the River Clyde", a name which had been coined in 1897 for the title of Baron Inverclyde which was conferred upon John Burns of Castle Wemyss, a large house at Wemyss Bay. The remaining parts of Renfrewshire were divided between the Eastwood and Renfrew districts. The three districts together formed a single lieutenancy area.[6]

In 1996 the districts and regions were replaced with unitary council areas under the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994. In the debates leading up to that act, the government initially proposed replacing these three districts with two council areas: "West Renfrewshire", covering Inverclyde district and the western parts of Renfrew district, and "East Renfrewshire", covering Eastwood district and the eastern parts of Renfrew district.[7] The proposals were not supported locally, with Inverclyde successfully campaigning to be allowed to form its own council area. The new council areas came into effect on 1 April 1996.[8][9]

Settlements

[edit]Settlements by population:

| Settlement | Population (2020)[10] |

|---|---|

| Greenock |

41,280 |

| Port Glasgow |

14,200 |

| Gourock |

10,210 |

| Kilmacolm |

3,930 |

| Inverkip |

3,490 |

| Wemyss Bay |

2,390 |

| Quarrier's Village |

710 |

Communities

[edit]The area is divided into eleven community council areas, seven of which have community councils as at 2023 (being those with asterisks in the list below):[11]

- Gourock*

- Greenock Central

- Greenock East

- Greenock Southwest*

- Greenock West and Cardwell Bay*

- Holefarm and Cowdenknowes

- Inverkip and Wemyss Bay*

- Kilmacolm*

- Larkfield, Braeside and Branchton*

- Port Glasgow East

- Port Glasgow West*

Places of interest

[edit]- Ardgowan Estate

- The Bogal Stone

- Cappielow

- Castle Levan

- Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park

- Greenock Cut Visitor Centre[12]

- Custom House Quay and Museum[13]

- Duchal House

- Finlaystone House

- Gourock Outdoor Pool[14]

- Granny Kempock Stone

- Loch Thom

- Lunderston Bay[12]

- McLean Museum and Art Gallery[15]

- Newark Castle[16]

- Waterfront Leisure Complex[17]

National voting

[edit]In the 2014 independence referendum, the "No" vote won in Inverclyde by just 86 votes and a margin of 0.2%. By either measure, this was the narrowest result of any of the 32 council areas. In the 2016 EU Referendum, Inverclyde posted a "Remain" vote of almost 64%.

Education

[edit]Inverclyde has twenty primary schools serving all areas of its settlements. These are:

- Aileymill Primary School, Greenock (merger of Larkfield and Ravenscraig primaries)

- All Saints Primary School, Greenock (merger of St. Kenneth's and St. Lawrence's primaries)

- Ardgowan Primary School, Greenock

- Gourock Primary School, Gourock

- Inverkip Primary School, Inverkip

- Kilmacolm Primary School, Kilmacolm/Port Glasgow

- King's Oak Primary School, Greenock (merger of King's Glen and Oakfield primaries)

- Lady Alice Primary School, Greenock

- Moorfoot Primary School, Gourock

- Newark Primary School, Port Glasgow (merger of Boglestone, Clune Park, Highholm and Slaemuir primaries)

- St. Andrew's Primary School, Greenock (merger of Sacred Heart and St. Gabriel's primaries)

- St. Francis' Primary School, Port Glasgow

- St. John's Primary School, Port Glasgow

- St. Joseph's Primary School, Greenock

- St. Mary's Primary School, Greenock

- St. Michael's Primary School, Port Glasgow

- St. Ninian's Primary School, Gourock

- St. Patrick's Primary School, Greenock

- Wemyss Bay Primary School, Wemyss Bay

- Whinhill Primary School, Greenock (merger of Highlanders' Academy and Overton primaries)

These are connected to several Secondary schools which serve Inverclyde as follows:

- Clydeview Academy, serving the West End of Greenock and the town of Gourock

- Inverclyde Academy, serving South and East Greenock as well as the villages of Inverkip and Wemyss Bay

- Notre Dame High School, serving Greenock

- Port Glasgow High School, serving Port Glasgow and Kilmacolm

- St Columba's High School, Gourock/Greenock, serving Gourock, Inverkip and Wemyss Bay

- St. Stephen's High School, serving Port Glasgow, Kilmacolm and the East End of Greenock

- Craigmarloch School which is an Additional Support Needs school for pupils aged 4–18 based at the new Port Glasgow Community Campus after the merging of Glenburn and Lilybank schools.

Demography

[edit]The average life expectancy for Inverclyde male residents (2013–2015) is 75.4 years, to rank 28th out of the 32 areas in Scotland. The average Inverclyde female lives for 80.4 years, to rank 26th out 32.[18] There are large health disparities between settlements in Inverclyde with many health indicators being above the Scottish average in certain areas, whilst considerably below in others.[19]

In 2019, the Inverclyde Council Area was rated as the most deprived in Scotland by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), with Greenock Town Centre the most deprived community. (The term "deprivation" refers not only to low income according to the BBC, but may also include "fewer resources and opportunities, for example in health and education".) After the announcement, Deputy leader Jim Clocherty said that he hoped that investment money would arrive soon, and that "no part of Scotland wants to be labelled as the 'most deprived'". A £3m investment was scheduled for Greenock Town Centre and there was also plan to create a new cruise visitor centre with other investment funds being expected.[20]

Religion

[edit]Inverclyde is one of only two Scottish council areas where 'no religion' was not the most common response to the question on religious adherence in the latest 2022 census. Census figures show that the most common religious denomination in Inverclyde was Roman Catholic, with 30,156 adherents (2011 Census) and 26,224 in the most recent 2022 census. Those who described their denomination as Church of Scotland fell to 18,554 in the same period.[21]

Languages

[edit]The 2022 Scottish Census reported that out of 76,542 residents aged three and over, 22,878 (29.9%) considered themselves able to speak or read the Scots language. [22]

The 2022 Scottish Census reported that out of 76,554 residents aged three and over, 660 (0.9%) considered themselves able to speak or read Gaelic. [23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Council and Government". Inverclyde Council. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Mid-Year Population Estimates, United Kingdom, June 2024". Office for National Statistics. 26 September 2025. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ^ "Glasgow and Clyde Valley Structure Plan Joint Committee". www.gcvcore.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1973 c. 65, retrieved 9 February 2023

- ^ "No. 14632". The Edinburgh Gazette. 7 March 1930. p. 258.

- ^ "The Lord-Lieutenants Order 1975", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1975/428, retrieved 9 February 2023

- ^ "Local Government (Scotland and Wales) Volume 233: debated on Monday 22 November 1993". Hansard. UK Parliament. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ "Local Government Etc (Scotland) Bill: Volume 235: debated on Monday 17 January 1994". Hansard. UK Parliament. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1994 c. 39, retrieved 6 February 2023

- ^ "Population estimates for settlements and localities in Scotland: mid-2020". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Community Council Pages". Inverclyde Council. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Clyde Muirshiel – Scotland's Largest Regional Park". clydemuirshiel.co.uk.

- ^ [1] Archived 23 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Online Member Services". www.inverclydeleisure.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2005.

- ^ "McLean Museum and Art Gallery - Inverclyde Council - Museum & Art Gallery". Archived from the original on 22 November 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2005.

- ^ "Historic Environment Scotland". www.historic-scotland.gov.uk.

- ^ "Online Member Services". www.inverclydeleisure.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2005.

- ^ "Life expectancy for areas within Scotland 2013–2015" (PDF). National records for Scotland. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Browser Health". Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ "Scotland's most and least deprived areas named". BBC News. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/webapi/opentable?id=019a2022-ecdd-77ea-96ad-569f0c5b3786

External links

[edit]Inverclyde

View on GrokipediaGovernance and Politics

Local Council Structure and Administration

Inverclyde Council functions as a unitary authority under Scottish local government legislation, delivering services such as education, housing, social care, and planning across the area. It comprises 22 elected councillors serving terms of five years, representing six multi-member wards: Inverclyde East (4 members), Inverclyde Central (3), Inverclyde East Central (3), Inverclyde North (4), Inverclyde West (4), and Inverclyde South West (4).[8][9] The full council holds ultimate responsibility for strategic decisions, including the annual budget and policy framework, with meetings typically convened monthly.[10] Decision-making powers are delegated to specialized committees to enhance efficiency and oversight. The Policy and Resources Committee manages corporate functions, including financial planning, performance monitoring, and directorate-level strategies.[11] Service-specific bodies include the Education and Communities Committee, which oversees schooling, community safety, housing strategy, and equalities initiatives; the Environment and Regeneration Committee, addressing planning, waste management, and economic development; and the Audit Committee, responsible for internal audits, risk management, and relations with external auditors.[12][13] Additional panels, such as the Social Work and Social Care Scrutiny Panel, provide targeted scrutiny of key services.[14] The administrative hierarchy is headed by the Chief Executive, Stuart Jamieson, who assumed office on 5 May 2025 following his appointment on 3 April 2025.[15][16] Operations are organized into four directorates: Chief Executive's Services (encompassing policy, communications, finance, legal, and digital functions, with key roles including Interim Chief Financial Officer Angela Edmiston and Head of Legal Services Lynsey Brown); Education, Communities and Organisational Development (led by Ruth Binks); Environment, Regeneration and Resources (with Interim Director of Regeneration Neale McIlvanney and Interim Director of Environment Eddie Montgomery); and the integrated Health and Social Care Partnership (Chief Officer Kate Rocks, incorporating Chief Social Work Officer Jonathan Hinds).[16] This structure supports the council's accountability to both elected members and the Scottish Government, with headquarters at the Municipal Buildings in Greenock.[16]Electoral History and Voting Patterns

Inverclyde has historically been a Labour stronghold in both national and local elections, reflecting its working-class demographics and legacy of industrial employment in shipbuilding and related sectors, though voting patterns shifted markedly toward the Scottish National Party (SNP) in the 2010s amid rising support for Scottish independence.[17] The area exhibited one of the closest results in the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, with 50.0% voting Yes (27,019 votes) and 49.98% voting No (26,994 votes) out of 54,013 counted papers, a turnout of 87.4%, which correlated with subsequent SNP electoral advances.[18] [19] This pro-independence lean contrasted with Scotland's overall No majority, influencing partisan realignments where SNP gains eroded Labour's dominance before a partial Labour recovery in recent contests. In UK Parliament elections, the former Inverclyde constituency (abolished in 2024 boundary changes) was held by Labour from its 2005 creation until the 2015 general election, when SNP candidate Ronnie Cowan defeated incumbent Iain McKenzie (Labour) amid a national SNP surge. Cowan retained the seat in 2017 and 2019 general elections. In the 2011 by-election—triggered by McKenzie's resignation—Labour's McKenzie secured victory with 15,118 votes (50.9%) against SNP's Anne McLaughlin's 9,280 (31.3%), reducing the majority to 5,838 from 14,416 in 2010, signaling early SNP pressure post-Scottish Parliament elections. The 2024 general election, under the new Inverclyde and Renfrewshire West constituency, saw Labour's Martin McCluskey win with 18,931 votes (48.3%) against Cowan's 12,560 (32.0%), reclaiming the area with a majority of 6,371 on a turnout of approximately 60%.[20] [17] [21] [22]| Year | Winner (Party) | Votes | % | Majority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 (by-election) | Iain McKenzie (Labour) | 15,118 | 50.9 | 5,838 |

| 2015 | Ronnie Cowan (SNP) | N/A | N/A | Gain from Labour |

| 2019 | Ronnie Cowan (SNP) | N/A | N/A | Hold |

| 2024 (new constituency) | Martin McCluskey (Labour) | 18,931 | 48.3 | 6,371 |

Policy Controversies and Criticisms

Inverclyde Council's education spending has drawn criticism for its heavy reliance on supply teachers, with expenditures totaling over £8 million since 2020, including £1.6 million in the most recent year reported, amid ongoing challenges in teacher recruitment and retention that have strained local budgets.[27] Critics, including opposition councillors, argue this reflects inefficiencies in workforce planning and failure to address underlying issues like low morale or inadequate training programs, exacerbating fiscal pressures in a deprived area.[27] Fiscal policies under the Labour-led administration have faced backlash for defying Scottish Government calls for a council tax freeze, implementing a rise in February 2024 that increased average bills despite opposition from the SNP group.[28] This decision, passed without an overall majority, was justified by council leaders as necessary to fund essential services amid funding shortfalls, but detractors highlighted it as burdensome for low-income households in a region with high deprivation rates, potentially undermining efforts to stimulate economic recovery.[28] Planning and development policies have been marred by ethical breaches and contentious decisions, such as the 2023 case where SNP councillor Innes Nelson was found to have violated the councillor code by failing to declare a conflict of interest in discussions over a 270-home cap on the former IBM site, influencing housing supply restrictions.[29] Similarly, the council's rejection of plans to convert a former Quarriers Village care home into housing in 2025 prompted appeals to overturn the decision, with proponents criticizing it as overly restrictive zoning that hinders affordable rental stock amid housing shortages.[30] These incidents underscore recurring concerns over transparency in policy-making, as evidenced by a 2025 leak inquiry into secretive funding for Inchgreen port improvements involving millions in taxpayer funds.[31] A 2025 probe into council tax discount fraud uncovered £102,801 in fraudulent claims, revealing vulnerabilities in welfare policy administration and prompting calls for tighter verification processes to prevent abuse while protecting legitimate recipients.[32] Additionally, a high-profile procurement failure in street lighting services led to the UK's first declaration of contract ineffectiveness against the council, highlighting procedural lapses that delayed infrastructure upgrades and incurred legal costs.[33] Such issues have fueled broader critiques of governance, with historical audits as early as 2005 labeling the council among Scotland's worst and mandating external intervention for systemic improvements.[34]History

Pre-Industrial Period

The Inverclyde region preserves evidence of early human activity from the Bronze Age, exemplified by a roundhouse settlement uncovered in Inverkip dating to the 15th–13th centuries BC, featuring wattle and daub construction, a central hearth, and artifacts such as pottery and flint tools, representing a rare lowland example of such domestic architecture.[35] Roman military presence arrived in the 2nd century AD, with the construction of a fortlet at Lurg Moor overlooking the Clyde estuary near Greenock around AD 139–142, forming part of the Antonine Wall's defensive network and including a well-preserved 180-meter segment of military road to facilitate coastal oversight and supply lines.[36] These installations underscored the area's strategic value along the empire's northwestern frontier, though occupation was temporary, ending by the mid-2nd century AD.[35] Medieval development centered on feudal strongholds and agrarian pursuits, with Newark Castle erected in 1478 by George Maxwell of Pollok on the Clyde shore near present-day Port Glasgow, serving as a fortified residence amid a small fishing community focused on herring; the structure was later remodeled in the late 1500s, incorporating Renaissance elements and timber dated to 1598.[37] Greenock, meanwhile, originated as a modest coastal hamlet under baronial control, its name likely deriving from Gaelic roots denoting a sunny or gravelly bay, with sparse settlement limited to fishing huts and reliance on local burns for water and small-scale netting by the 13th century.[38] The landscape remained predominantly rural, with wooded hillsides like Devol Glen supporting limited agriculture and forestry into the 17th century.[38] By the early modern period, Greenock coalesced around the Old West Kirk, founded in 1591–1592 by John Schaw under a charter from James VI permitting church, manse, and graveyard construction, which anchored a community of around 800 souls by 1627, primarily engaged in herring fisheries granted royal privileges as early as 1526.[38] A 1635 charter from Charles I elevated Greenock to burgh of barony status, enabling systematic land feuing from 1636 and rudimentary infrastructure like jetties in Sir John's Bay, while Newark persisted as a herring-centric village until Glasgow merchants acquired adjacent lands in 1668 for docking, presaging later expansion.[38][39] Economic activity hinged on seasonal fishing yields, exporting 20,000 barrels of salted herring by 1674, supplemented by basic maritime ventures such as the 1649 commissioning of the Frigate of Greenock, though the harbor remained primitive, comprising whinstone heaps and natural anchorages like the Bay of Quick.[38] Population stayed small, numbering 746 inhabitants in 1694, with governance vested in local heritors and strict ecclesiastical oversight enforcing communal discipline.[38]Rise of Shipbuilding and Industry

The shipbuilding industry in Inverclyde emerged prominently in the 18th century, driven by the region's strategic position on the lower Clyde where deeper waters accommodated ocean-going vessels unable to navigate upstream to Glasgow. Greenock's first square-rigged vessel, a brig named Greenock for the West Indian trade, was constructed in 1760, marking an early milestone in local maritime output. By the mid-18th century, multiple yards operated in Greenock, with Scotts Shipbuilding & Engineering Co., established in 1711, laying foundations for sustained growth through wooden vessel construction. Port Glasgow similarly developed as a shipbuilding hub, importing vast quantities of timber to support expanding yards amid rising global demand for merchant and naval ships.[40][41] The 19th century saw Inverclyde's shipyards achieve world-leading status, producing diverse vessels including clippers, steamships, and liners that bolstered British maritime dominance. Local records document nearly 10,000 ships built across Inverclyde's yards during this peak era, contributing significantly to the Clyde's output of over 20% of global shipping tonnage. Key firms like Russell and Co. in Port Glasgow standardized designs, launching 271 vessels between 1882 and 1892 alone, while Scotts advanced steam technology, experimenting with high-pressure compound engines to enhance efficiency. These innovations, coupled with trade booms in tobacco and sugar, fueled employment surges and positioned Greenock as a premier port by 1829, with vessels trading worldwide.[42][43][44][45] Complementary industries amplified Inverclyde's industrial rise, with sugar refining becoming a cornerstone after the first refinery opened in Greenock in 1765, backed by West Indian merchants processing imported raw cane. By the 1870s, 14 to 15 major refineries operated locally, yielding a quarter-million tons annually and ranking Greenock second only to London in output, reliant on Clyde shipping for raw materials despite earlier colonial ties. Gourock Ropeworks, founded in 1736, grew into the world's largest rope producer by the 19th century, supplying shipyards with essential cordage and employing thousands in specialized manufacturing. Engineering firms, integrated with shipbuilding, developed ancillary technologies like propulsion systems, creating a clustered ecosystem of skilled labor and innovation that transformed Inverclyde from agrarian settlements into an industrial powerhouse.[46][47][48][49]Post-War Decline and Deindustrialization

The shipbuilding sector in Inverclyde, centered in Greenock and Port Glasgow, initially benefited from post-World War II reconstruction orders but began facing structural challenges by the late 1950s due to outdated facilities, high labor costs, and rising competition from modernized foreign shipyards in Japan and Europe. Output from local yards declined as global overcapacity emerged, with British shipbuilding's share of world orders falling from 30% in 1955 to under 5% by 1975.[50] Mergers were attempted to rationalize operations; in 1967, Greenock's historic Scotts Shipbuilding and Engineering Company merged with Port Glasgow's Lithgows to form Scott Lithgow Ltd., consolidating resources amid shrinking domestic demand.[51] Despite temporary booms from North Sea oil-related contracts in the 1970s, inefficiencies persisted, exacerbated by the broader Clyde region's turmoil, including the 1971 Upper Clyde Shipbuilders liquidation, which signaled the vulnerability of Scotland's heavy industry and contributed to skilled labor shortages in adjacent areas like Inverclyde.[52] Nationalization of Scott Lithgow into British Shipbuilders in 1977 aimed to stem losses through subsidies and restructuring, but chronic underbidding on contracts and technological lags led to mounting deficits, with the company reporting £100 million in losses by the early 1980s.[53] Privatization efforts under the Thatcher government failed to revive viability; a controversial 1983 bid for a Norwegian contract collapsed due to cost overruns, prompting receivership in January 1984 and the effective cessation of major shipbuilding by 1985, though some engineering lingered until final trading halted in 1993.[54] [51] This closure eliminated thousands of direct jobs, rippling through supply chains; between 1976 and 1980, 4,580 redundancies were recorded in Greenock alone, with female unemployment surging as ancillary manufacturing like textiles collapsed, exemplified by the 1981 Lee Jeans factory occupation protesting 300 job losses.[55] Deindustrialization accelerated socioeconomic fallout, with male unemployment in the Clydeside conurbation, including Inverclyde, peaking at 21% in 1984 amid Scotland-wide manufacturing losses of 20,000 jobs annually from 1979 to 1987.[56] [57] The area's reliance on heavy industry—once employing over 10,000 in shipyards—left a legacy of derelict sites, population decline from 114,000 in 1961 to under 85,000 by 1991, and entrenched deprivation, as engineering and dock-related trades evaporated without viable alternatives.[58] Government interventions, such as enterprise zones in the 1980s, provided limited mitigation, underscoring causal links between lost export-oriented industries and persistent regional inequality.Contemporary Developments

In the decades following the near-total collapse of traditional shipbuilding by the 1980s, Inverclyde experienced prolonged economic stagnation, with unemployment rates peaking above 20% in the early 1990s amid factory closures and outmigration of skilled workers.[6] This period saw the area designated as one of Scotland's most deprived regions, with slow recovery in health outcomes; for instance, mortality rates in west central Scotland, including Inverclyde, improved more gradually than in comparator post-industrial zones between 1981 and 2001.[59] Community-led responses emerged, such as early experiments in social enterprises during the 1970s-1990s that evolved into a moral economy framework to address industrial absence through local cooperatives and training schemes.[58] Regeneration efforts intensified from the late 1990s, focusing on waterfront and urban renewal to leverage the area's Clyde estuary location. The Greenock Waterfront initiative, launched in the early 1990s with public-private investment, transformed derelict docklands into mixed-use spaces, though evaluations in 2002 highlighted mixed economic impacts including modest job creation in retail and tourism.[60] By the 2010s, heritage tourism gained traction, exemplified by the 2011 Tall Ships race visit to Greenock, which drew over 100,000 visitors and spurred temporary boosts in local spending, as documented in the 2019-2029 Inverclyde Heritage Strategy.[61] These projects coincided with broader Scottish devolution policies post-1999, which allocated funds for infrastructure but yielded uneven growth, with Inverclyde's GDP per capita lagging national averages into the 2020s.[62] Into the 2020s, targeted infrastructure and sustainability projects marked a shift toward housing-led recovery and environmental restoration. A £22 million Greenock town centre redevelopment, including pedestrianization and commercial revitalization, commenced construction in early 2025 to address vacant units and stimulate retail footfall.[63] Concurrently, a £1.5 million investment in Port Glasgow's town centre aimed to enhance public realms and business viability, approved in October 2025.[64] In Inverkip, a £4 million A78 road upgrade, initiated in April 2025, facilitated plans for 650 new homes and over 500 jobs by improving access to undeveloped sites.[65] Demolition of the derelict Lilybank estate—nicknamed "Scotland's Chernobyl" for its abandoned state since the 2010s—began in April 2025 to clear land for potential redevelopment amid ongoing deprivation challenges.[66] Peatland restoration at Duchal Moor, covering 788 hectares and funded through 2021-2024 initiatives, sought to reduce carbon emissions while creating green jobs, earning sustainability awards in 2024.[67] These developments reflect persistent efforts to diversify beyond legacy industries, though analysts note risks of further decline without sustained national investment in sectors like renewables.[68]Geography

Physical Features and Location

Inverclyde occupies a position on the southern shore of the Firth of Clyde in west central Scotland, approximately 40 kilometres west of Glasgow city centre.[69] The council area spans 162 square kilometres in the Lowlands region, bounded by Renfrewshire to the east and north, and otherwise fronting the firth to the west and south.[70] The landscape consists of a densely developed coastal strip along the Clyde estuary, supporting urban settlements and port infrastructure, which gives way inland to more sparsely populated rolling hills and upland terrain. The highest elevation within Inverclyde reaches 441 metres at Creuch Hill.[71] The region's coastline features sheltered bays and deep-water access characteristic of the firth, facilitating maritime activities, while inland drainage occurs via small streams feeding into the Clyde system.[70]Settlements and Urban Structure

Inverclyde's settlements form a compact urban-rural mosaic, with principal towns aligned linearly along the southern shore of the Firth of Clyde and smaller villages dispersed inland and on the coast. The core urban area comprises Greenock, Port Glasgow, and Gourock, interconnected by continuous development reflecting historical shipbuilding expansion, while villages such as Kilmacolm, Quarrier's Village, Inverkip, and Wemyss Bay offer contrasting rural and semi-rural environments. This structure is shaped by the area's topography, featuring a narrow coastal plain that rises steeply to moorland heights, limiting sprawl and concentrating population in established locales.[72][73] Greenock, the dominant settlement with an estimated 43,000 residents, functions as the council's administrative hub, encompassing commercial districts, waterfront facilities, and institutional buildings. Port Glasgow, adjacent to the east with about 15,000 inhabitants, and Gourock to the west, population around 10,000, extend the urban continuum, supporting maritime activities including ferry terminals at Gourock and residential expansion. The villages, each numbering 3,000 to 4,000 people, maintain distinct identities: inland Kilmacolm and Quarrier's Village emphasize amenity and heritage, whereas coastal Inverkip and Wemyss Bay feature harbors and rail links.[72] Spanning 62 square miles, Inverclyde exhibits a population density of approximately 489 persons per square kilometer, underscoring the intensity of its coastal urban strip against the sparsely populated hinterland, including parts of the Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park. Planning policy prioritizes infill development and regeneration within these settlements to safeguard green belt land and rural landscapes from further urbanization.[72][74]Economy

Traditional Industries and Their Legacy

Inverclyde's traditional industries were centered on shipbuilding and associated maritime activities, which propelled the region to prominence from the early 19th century onward. Shipyards in Greenock and Port Glasgow, including notable operations like those of John Wood, Caird & Company, and later Scott Lithgow, constructed a wide array of vessels, from commercial ships to naval craft, leveraging the River Clyde's strategic position.[49][75] The industry peaked between 1875 and 1914, during which Inverclyde emerged as one of the world's leading shipbuilding communities, supported by booms in global trade and wartime demands.[76][42] Complementary sectors, such as engine manufacturing and steering gear production, also thrived, drawing on innovations linked to figures like James Watt and fostering a dense cluster of skilled labor.[77] The post-World War I era brought initial setbacks through economic depression, but shipbuilding sustained significant employment into the mid-20th century, with yards like Scott Lithgow achieving milestones such as record launches in 1969.[75] However, intensified global competition, technological shifts, and nationalization under British Shipbuilders precipitated sharp decline from the 1970s, culminating in the loss of over 4,000 jobs in the Greenock and Port Glasgow area alone between 1983 and 1985.[78] By the late 20th century, the closure of major yards marked the end of heavy industry dominance, leaving behind derelict waterfronts and a workforce ill-equipped for service-oriented economies.[79] The legacy of these industries persists in Inverclyde's socioeconomic fabric, contributing to chronic unemployment, depopulation, and entrenched deprivation as manufacturing sites shuttered en masse in the 1980s.[49][57] This deindustrialization fostered a "long shadow" of job loss, with ripple effects including rising poverty and welfare dependency that regeneration efforts have struggled to fully mitigate.[80][81] While the maritime heritage underscores the area's engineering prowess and global connectivity, it also highlights vulnerabilities to exogenous shocks, prompting diversification into tourism and lighter industries without erasing the structural challenges inherited from industrial collapse.[6]Current Economic Indicators and Challenges

Inverclyde's employment rate for working-age adults (aged 16-64) stood at 65.8% for the period October 2023 to September 2024, significantly below the Scottish average of 74% and the Great Britain figure of 75.5%.[82] The unemployment rate in the same period was 4.2%, exceeding Scotland's 3.3% and Great Britain's 3.7%.[82] Economic inactivity affected 30% of the working-age population, compared to 23.4% in Scotland and 21.6% in Great Britain, with total employment numbering approximately 24,000 in 2023, reflecting a 17% decline since 2015 while Scotland's employment rose by 4%.[82]| Indicator (Oct 2023–Sep 2024) | Inverclyde | Scotland | Great Britain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Rate (%) | 65.8 | 74.0 | 75.5 |

| Unemployment Rate (%) | 4.2 | 3.3 | 3.7 |

| Economic Inactivity Rate (%) | 30.0 | 23.4 | 21.6 |

Regeneration Efforts and Recent Initiatives

Inverclyde's regeneration efforts have been guided by the Economic Regeneration Strategy 2021-2025, which emphasizes skills development, business growth, job creation, and mitigation of post-Brexit and COVID-19 impacts through community benefits and carbon reduction measures. This framework supports targeted investments in infrastructure and enterprise, including expansions at business parks and waterfront developments to leverage the area's Clyde estuary location. Complementing this, the Council's Repopulation Strategy 2025-2028 prioritizes housing-led regeneration to attract residents, alongside job opportunities and inequality reduction. A proposed £70 million regeneration wishlist submitted to the UK government in August 2023 outlined priorities such as a £3 million expansion of Kelburn Business Park by 55,000 square feet and broader revitalization of derelict sites to foster private sector activity.[84] In October 2023, the UK government allocated £20 million specifically for Greenock and Inverclyde to enhance town center viability and infrastructure, aiming to address long-term deindustrialization effects.[85] Scottish Government funding of £1.5 million in May 2025 supported 17 community and business projects, including lighting upgrades at Battery Park and landscaping at the Shipbuilders of Port Glasgow heritage site.[86] Recent waterfront initiatives include the August 2025 conditional sale of the James Watt Dock site, including the A-listed Titan crane and Sugar Sheds, to Glasgow Arts Centre Limited for mixed-use development incorporating food and beverage outlets, leisure facilities, and residential units, pending planning approval.[87] Plans for the Titan crane potentially feature the UK's longest urban zipline to draw tourism.[88] In Greenock town center, a £24 million transformation project commenced in autumn 2025, focusing on public realm improvements and economic revitalization.[89] Sustainability efforts, such as peatland restoration and tree planting, earned awards in 2024, integrating environmental goals with economic aims.[90] These initiatives build on broader placemaking under the Local Development Plan, targeting 25.73 hectares of developable land and over 23,000 square meters of new business space, though outcomes remain contingent on funding realization and market uptake amid ongoing socioeconomic challenges.[91]Demographics and Society

Population Dynamics and Migration

The population of Inverclyde declined from 84,203 in the 2001 census to 81,485 in 2011 and 78,426 in 2022, marking a cumulative decrease of 6.9% by mid-2023—the sharpest among Scotland's 32 council areas.[74][92] This trend reflects post-industrial economic stagnation, with the area recording one of Scotland's highest depopulation rates over the past decade.[93] Negative natural change—deaths outnumbering births—has been the dominant factor, with 35,167 deaths versus 27,108 births from 1991 to 2022, yielding a 23% deficit.[94] Mid-year estimates show a 0.5% drop to 76,700 by June 2021, continuing into stable but low levels around 78,300 by 2023.[95] Projections forecast a further 5.1-5.4% decline by the early 2030s, driven primarily by aging demographics and low fertility rather than migration outflows.[96] Historically, net out-migration of working-age residents, spurred by shipbuilding collapse and limited job prospects, exacerbated depopulation, though data indicate sporadic positive net flows since mid-2016.[95] Recent reversals show net in-migration of +500 between mid-2022 and mid-2023 (1,940 inflows against 1,440 outflows), ranking 27th among Scottish areas but insufficient to counter natural losses.[74] Internal movements dominate, often from Glasgow for cheaper housing, while international in-migration remains modest at 3.5% foreign-born (2,761 individuals in 2022), with over 800 overseas arrivals in 2023-24.[97][98] These patterns underscore causal links to socioeconomic deprivation, where youth exodus persists despite affordability drawing retirees and families.[99]Socioeconomic Deprivation and Welfare Dependency

Inverclyde ranks among the most deprived areas in Scotland according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 2020, with 45% of its data zones classified within the 20% most deprived nationwide, the highest local share of any council area.[100] The SIMD encompasses domains including income, employment, health, education, and housing, revealing concentrated deprivation in urban centers like Greenock, where the most deprived data zone in all of Scotland—ranked 1 overall—is located in the town center, exhibiting an income deprivation rate of 48%.[101] [102] Approximately 44.7% of Inverclyde's data zones fall into the 20% most deprived quintile across multiple indicators, reflecting persistent structural challenges from the decline of traditional industries such as shipbuilding.[103] Child poverty rates underscore the extent of socioeconomic strain, with 26.1% of children (over 3,500 individuals) living in poverty in 2022/23, though this declined to 22.4% by 2024 amid targeted interventions like the Scottish Child Payment.[104] [105] Relative poverty affects nearly one in four children, exceeding national averages and correlating with higher rates of households reliant on welfare support, including crisis grants from the Scottish Welfare Fund, where Inverclyde recorded an 84% acceptance rate in 2024/25—the highest in Scotland—indicating acute demand for emergency aid.[106] Over £33 million in benefits were disbursed across the area in the 2023/24 financial year, supporting vital needs amid limited local employment opportunities.[107] Employment metrics highlight welfare dependency, with an employment rate of 68.4% for ages 16-64 in the year ending December 2023, below the Scottish average of approximately 74%, and an economic inactivity rate elevated due to long-term health issues and skills mismatches from industrial legacy.[108] The claimant count stands at 3.6% for working-age adults, with out-of-work benefits encompassing a broad group under Universal Credit, reflecting structural barriers to re-entry into the labor market.[109] These patterns persist despite some progress, such as a drop in unemployment to 3.8%, as deindustrialization has entrenched intergenerational reliance on state support, with 15% of households classified as multiply or severely deprived.[108] [110]Cultural and Religious Composition

In the 2022 Scotland Census, Roman Catholicism was the most commonly reported religion in Inverclyde, with 33.4% of respondents identifying as Roman Catholic, reflecting historical Irish immigration patterns tied to the region's shipbuilding and industrial workforce demands in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[111] No religion followed closely at 32%, an increase from previous censuses that aligns with broader secularization trends in Scotland but lags behind the national figure of 51.1%.[112] The Church of Scotland, traditionally dominant in Scotland, accounted for approximately 23.5% or 18,554 individuals, down from higher shares in earlier decades.[112]| Religion | Percentage | Approximate Number (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 33.4% | 26,000 |

| No religion | 32% | 25,268 |

| Church of Scotland | 23.5% | 18,554 |

| Other Christian | ~5-10% (estimated from total Christian reports) | Varies |

| Other religions (e.g., Muslim, Hindu) | <2% | <1,500 |

Education and Human Capital

Educational Institutions and Attainment

Inverclyde operates 20 primary schools, 6 secondary schools, 20 early years establishments, and 3 additional support needs (ASN) units to serve its pupil population.[119] The secondary schools include Clydeview Academy, Inverclyde Academy, Notre Dame High School, Port Glasgow High School, St Columba's High School, and St Stephen's High School.[120] Further education is primarily provided through the Greenock campus of West College Scotland, a merged institution formed in 2013 from James Watt College and others, offering vocational, higher national, and degree-level courses to support regional skills development and address attainment gaps.[121][122] School leaver attainment in Inverclyde exceeded national averages in 2022-23, with 97.4% of leavers achieving one or more passes at Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) Level 4 or better, compared to 96.0% across Scotland; 86.7% at Level 5 or better (versus 84.8% nationally); and 60.2% at Level 6 or better (versus 57.9%).[123] These figures reflect progress amid high socioeconomic deprivation in parts of the area, where targeted interventions via the Attainment Scotland Fund and data-driven pupil tracking have contributed to closing poverty-related gaps.[124] Recent Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) results indicate continued improvement: in 2024, pass rates reached 89% at Higher and Advanced Higher levels, and 88% at National 5; by 2025, National 5 passes rose to 90.8%, with 65% of S5 pupils attaining at least one Higher.[125][126] Among state secondary schools, performance varies, with none in Scotland's top 10% but consistent gains in literacy and numeracy priorities under national improvement frameworks.[127]| SCQF Level | Inverclyde (2022-23) | Scotland (2022-23) |

|---|---|---|

| Level 4 or better | 97.4% | 96.0% |

| Level 5 or better | 86.7% | 84.8% |

| Level 6 or better | 60.2% | 57.9% |