Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Afterimage

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

An afterimage, or after-image, is an image that continues to appear in the eyes after a period of exposure to the original image. An afterimage may be a normal phenomenon (physiological afterimage) or may be pathological (palinopsia). Illusory palinopsia may be a pathological exaggeration of physiological afterimages. Afterimages occur because photochemical activity in the retina continues even when the eyes are no longer experiencing the original stimulus.[1][2]

The remainder of this article refers to physiological afterimages. A common physiological afterimage is the dim area that seems to float before one's eyes after briefly looking into a light source, such as a camera flash. Palinopsia is a common symptom of visual snow.

Negative afterimages

[edit]Negative afterimages are generated in the retina but may be modified like other retinal signals by neural adaptation of the retinal ganglion cells that carry signals from the retina of the eye to the rest of the brain.[3]

Normally, any image is moved over the retina by small eye movements known as microsaccades before much adaptation can occur. However, if the image is very intense and brief, or if the image is large, or if the eye remains very steady, these small movements cannot keep the image on unadapted parts of the retina.

Afterimages can be seen when moving from a bright environment to a dim one, like walking indoors on a bright snowy day. They are accompanied by neural adaptation in the occipital lobe of the brain that function similar to color balance adjustments in photography. These adaptations attempt to keep vision consistent in dynamic lighting. Viewing a uniform background while adaptation is still occurring will allow an individual to see the afterimage because localized areas of vision are still being processed by the brain using adaptations that are no longer needed.

The Young-Helmholtz trichromatic theory of color vision postulated that there were three types of photoreceptors in the eye, each sensitive to a particular range of visible light: short-wavelength cones, medium-wavelength cones, and long-wavelength cones. Trichromatic theory, however, cannot explain all afterimage phenomena. Specifically, afterimages are the complementary hue of the adapting stimulus, and trichromatic theory fails to account for this fact.[4]

The failure of trichromatic theory to account for afterimages indicates the need for an opponent-process theory such as that articulated by Ewald Hering (1878) and further developed by Hurvich and Jameson (1957).[4] The opponent process theory states that the human visual system interprets color information by processing signals from cones and rods in an antagonistic manner. The opponent color theory is that there are four opponent channels: red versus cyan, green vs magenta, blue versus yellow, and black versus white. Responses to one color of an opponent channel are antagonistic to those of the other color. Therefore, a green image will produce a magenta afterimage. The green color adapts the green channel, so they produce a weaker signal. Anything resulting in less green is interpreted as its paired primary color, which is magenta (an equal mixture of red and blue).[4]

Positive afterimages

[edit]Positive afterimages, by contrast, appear the same color as the original image. They are often very brief, lasting less than half a second. The cause of positive afterimages is not well known, but possibly reflects persisting activity in the brain when the retinal photoreceptor cells continue to send neural impulses to the occipital lobe.[5]

A stimulus which elicits a positive image will usually trigger a negative afterimage quickly via the adaptation process. To experience this phenomenon, one can look at a bright source of light and then look away to a dark area, such as by closing the eyes. At first one should see a fading positive afterimage, likely followed by a negative afterimage that may last for much longer. It is also possible to see afterimages of random objects that are not bright, only these last for a split second and go unnoticed by most people.[citation needed]

On empty shape

[edit]An afterimage in general is an optical illusion that refers to an image continuing to appear after exposure to the original image has ceased. Prolonged viewing of the colored patch induces an afterimage of the complementary color (for example, yellow color induces a bluish afterimage). The "afterimage on empty shape" effect is related to a class of effects referred to as contrast effects.[citation needed]

In this effect, an empty (white) shape is presented on a colored background for several seconds. When the background color disappears (becomes white), an illusionary color similar to the original background is perceived within the shape.[citation needed] The mechanism of the effect is still unclear, and may be produced by one or two of the following mechanisms:

- During the presentation of the empty shape on a colored background, the colored background induces an illusory complementary color ("induced color") inside the empty shape. After the disappearance of the colored background an afterimage of the "induced color" might appear inside the "empty shape". Thus, the expected color of the shape will be complementary to the "induced color", and therefore similar to the color of the original background.

- After the disappearance of the colored background, an afterimage of the background is induced. This induced color has a complementary color to that of the original background. It is possible that this background afterimage induces simultaneous contrast on the "empty shape". Simultaneous contrast is a psychophysical phenomenon of the change in the appearance of a color (or an achromatic stimulus) caused by the presence of a surrounding average color (or luminance).

Gallery

[edit]-

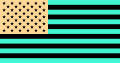

The U.S. flag inverted: if a viewer stares at the middle stripe for around 25 to 30 seconds, then looks at a wall and blink rapidly, this image will appear in color.

-

The Italian flag inverted: if a viewer stares at the middle of the flag long enough and blinks at a wall rapidly afterwards, this flag will appear in color.

-

Example video which produces a distorted illusion after one watches it and looks away. See motion aftereffect.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Bender, MB; Feldman, M; Sobin, AJ (Jun 1968). "Palinopsia". Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 91 (2): 321–38. doi:10.1093/brain/91.2.321. PMID 5721933.

- ^ Gersztenkorn, D; Lee, AG (Jul 2, 2014). "Palinopsia revamped: A systematic review of the literature". Survey of Ophthalmology. 60 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2014.06.003. PMID 25113609.

- ^ Zaidi, Q.; Ennis, R.; Cao, D.; Lee, B. (2012). "Neural locus of color afterimages. ". Current Biology. 22 (3): 220–224. Bibcode:2012CBio...22..220Z. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.021. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-000F-4AA5-4. PMC 3562597. PMID 22264612. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Horner, David. T. (2013). "Demonstrations of Color Perception and the Importance of Colors". In Ware, Mark E.; Johnson, David E. (eds.). Handbook of Demonstrations and Activities in the Teaching of Psychology. Vol. II: Physiological-Comparative, Perception, Learning, Cognitive, and Developmental. Psychology Press. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-1-134-99757-2. Retrieved 2019-12-06. Originally published as: Horner, David T. (1997). "Demonstrations of Color Perception and the Importance of Contours". Teaching of Psychology. 24 (4): 267–268. doi:10.1207/s15328023top2404_10. ISSN 0098-6283. S2CID 145364769.

- ^ "positiveafterimage". www.exo.net.

External links

[edit]- The Palinopsia Foundation is dedicated to increasing awareness of palinopsia, to funding research into the causes, prevention and treatments for palinopsia, and to advocating for the needs of individuals with palinopsia and their families.

- Eye On Vision Foundation raises money and awareness for persistent visual conditions

- Afterimages, a small demonstration.

- afterimage examples Archived 2015-06-18 at the Wayback Machine