Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

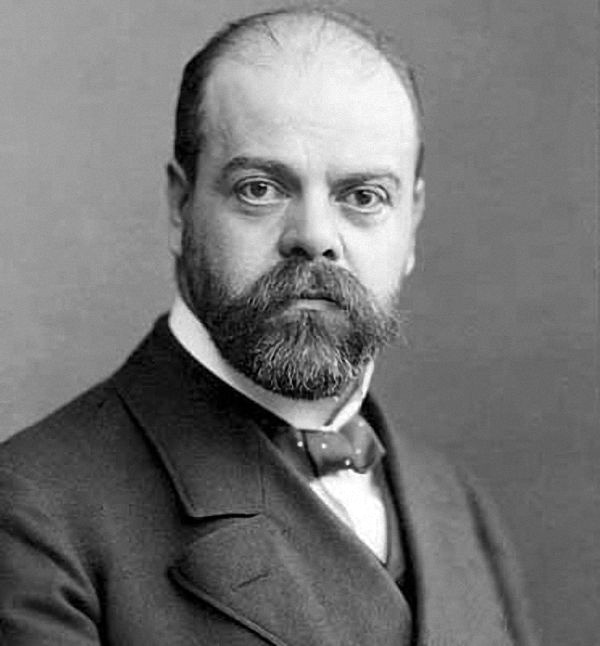

Alexander Parvus

View on WikipediaAlexander Israel Helphand (born Israel Lazarevich Gelfand, Russian: Израиль Лазаревич Гельфанд; 27 August 1867 – 12 December 1924), better known as Alexander Parvus, was a Russian-born Marxist theorist, journalist, and activist who became a prominent figure in the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

Key Information

Parvus is best known for his collaboration with Leon Trotsky in developing the theory of permanent revolution around 1905, and for his controversial role during World War I. He devised a plan to destabilize the Russian Empire by promoting internal revolution, which he presented to the German government. With German financial support, he established a network to aid the Bolsheviks and is widely remembered for his part in arranging Vladimir Lenin's return to Russia from exile in the "sealed train" in 1917.

After the Bolsheviks came to power, Lenin rejected Parvus's request to return to Russia, stating that "the cause of the revolution should not be touched by dirty hands". Parvus remained in Germany, becoming a wealthy industrialist and a political advisor to leaders of the Weimar Republic. His life was marked by sharp contrasts between his revolutionary activities, his intellectual contributions to Marxism, and his later affluence and political maneuvering, which made him an enigmatic and highly controversial figure.

Early life and education (1867–1891)

[edit]Israel Lazarevich Gelfand was born on 27 August 1867 into a lower middle-class Jewish family in Berezino, in the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire. His father was an artisan, possibly a locksmith or blacksmith.[1] When Gelfand was a child, his family's home was destroyed in a fire, an event he later recalled vividly. The family subsequently relocated to Odessa, his father's birthplace, in the early 1870s.[2]

In Odessa, Gelfand attended a gymnasium that emphasized classical studies. His most significant intellectual development, however, came from outside formal education. He became an admirer of the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko and was introduced to the idea of class struggle through Shevchenko's works on the Haidamakas. He was also influenced by Russian radical figures such as the sociologist Nikolay Mikhaylovsky and the satirist Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. The first work on political economy he read was a Russian edition of John Stuart Mill's work, annotated by Nikolay Chernyshevsky.[3] These influences fostered a reasoned contempt for the Tsarist order. In 1885, at the age of 18, he spent a year "going to the people", working as a locksmith's apprentice and traveling between workshops to get to know the working class.[4]

In 1886, Gelfand traveled abroad for the first time, hoping that "travel would resolve my political doubts".[4] He went to Zürich, Switzerland, a center for Russian revolutionary exiles, where he read the works of Alexander Herzen and other revolutionary literature. He became attracted to the nascent Russian Marxist movement, particularly the Emancipation of Labour group founded by Georgi Plekhanov. However, he remained troubled by the fact that Plekhanov's programme had "no place for the peasantry" in what was an overwhelmingly agricultural country.[5]

After a brief return to Russia, Gelfand left his native country permanently in 1887. He decided to pursue higher education, enrolling at the University of Basel in Switzerland in the autumn of 1888.[6] He studied political economy under Professor Karl Bücher, who influenced him with an emphasis on empirical analysis and hard facts.[7] Gelfand spent four years at the university, during which he became a convinced "scientific" socialist under the influence of Karl Marx. In 1891, he received his doctorate with a dissertation titled Technische Organisation der Arbeit, which examined the division of labor from a Marxist perspective. His degree was granted rite, the equivalent of a third-class pass, as his Marxist approach received little sympathy from his examiner.[8] It was at this time that he adopted the name Alexander, appearing on official records as Israel Alexander Helphand.[9]

Social Democratic journalist in Germany (1891–1904)

[edit]After completing his studies in 1891, Helphand decided against returning to Russia or joining the exiled Russian revolutionaries, whom he viewed as a "dead branch, cut off from the living body of the people".[10] Instead, he moved to Germany to join the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), convinced that Germany was the country most advanced on the path to socialism and that the world revolution would be decided there.[11] He later wrote, "My parting of company with the Russian intelligentsia dates from that time."[12]

He settled first in Stuttgart, where he was welcomed by Karl Kautsky, the editor of the SPD's leading theoretical journal, Die Neue Zeit, and the socialist activist Clara Zetkin. Kautsky recognized Helphand's talent and published his first articles.[13] By the end of 1891, Helphand moved to Berlin, the center of German politics. He lived in extreme poverty, taking a cheap room in a working-class district and walking several miles to the offices of the party newspaper Vorwärts because he could not afford tram fare or postage.[14] Despite his circumstances, he made an indelible impression on his German comrades with his exuberant, larger-than-life personality and powerful intellect.[14]

His first major success as a journalist came in 1892 with a series of articles in Vorwärts on the Russian famine of 1891–1892. He argued that the famine was a "chronic illness of long standing" resulting from Russia's transition to capitalism and predicted that the Russian bourgeoisie would be an unreliable revolutionary force.[15] His analysis was considered authoritative by the SPD and established him as an expert on Russian affairs. His literary activities soon drew the attention of the Prussian police, and at the beginning of 1893, he was served with a deportation order as an undesirable alien.[16]

For the next two years, Helphand lived as a wandering scholar, traveling between Dresden, Leipzig, Munich, and Stuttgart.[17] In 1894, he adopted the pseudonym Parvus for an article in Die Neue Zeit attacking the Bavarian socialists' decision to support the state budget. The article, titled "Keinen Mann und keinen Groschen" ("Not a single man and not a single penny"), caused a sensation and established the name Parvus in the socialist movement.[18] This was followed by a career as an editor, first at the Leipziger Volkszeitung and later at the Sächsische Arbeiterzeitung in Dresden, which he built into a profitable enterprise.[19]

Throughout the 1890s, Parvus became a prominent and outspoken voice on the radical left of the SPD. He engaged in major theoretical debates, arguing against the party's proposed agrarian program as unrealistic and non-revolutionary,[20] advocating for the political mass strike as a weapon of the proletariat,[21] and launching a fierce assault on the revisionist theories of Eduard Bernstein. He accused Bernstein of the "destruction of socialism" and demanded a social revolution.[22] His uncompromising radicalism and abrasive tone led to a "deep humiliation" at the 1898 Stuttgart party congress, where he was condemned by party leaders like August Bebel.[23] That same year, he was expelled from Saxony and moved to Munich.[24]

1905 Russian Revolution

[edit]

In Munich, which became his "Schwabing Headquarters", Parvus's focus shifted back towards Russia as he came into close contact with a new generation of Russian Marxist exiles.[25] In 1900, he was instrumental in persuading Vladimir Lenin, Julius Martov, and Alexander Potresov to publish their new newspaper, Iskra, in Germany.[26] Parvus's apartment became a focal point for the Russian revolutionaries; he assisted Lenin, who was living illegally in Munich, and hosted figures like Rosa Luxemburg and, later, Leon Trotsky.[27]

Parvus met Trotsky for the first time in the spring of 1904. It marked the beginning of a brief but intense intellectual partnership that profoundly influenced Trotsky's development.[28] As Trotsky later wrote, Parvus's ideas "definitively transformed the conquest of power by the proletariat from an astronomic 'final' goal to a practical task of our own day".[29] Following the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, Parvus published a series of articles in Iskra titled "War and Revolution," which argued that the war would lead to revolution in Russia and that the Russian proletariat would take over the role of the avant-garde of the social revolution.[30] This work laid the foundation for the theory of permanent revolution, which he and Trotsky jointly developed.[31]

When the 1905 Russian Revolution began, both Parvus and Trotsky saw it as the confirmation of their theories. After the October strike, Parvus returned to Russia, arriving in St. Petersburg at the end of the month.[32] He and Trotsky took over the small liberal newspaper Russkaya Gazeta and transformed it into a mass-circulation socialist daily, reaching a peak of 500,000 copies.[33] They became the dominant leaders of the St. Petersburg Soviet, with Trotsky as its public voice and Parvus as a key strategist and publicist.[34] Parvus was the primary author of the "Financial Manifesto" of December 1905, which urged citizens to undermine the state by withdrawing their deposits from banks in gold.[35]

After the government crushed the Soviet, Parvus was arrested in April 1906.[36] He was imprisoned first in the Cross Prison and later in the Peter and Paul Fortress.[37] Unlike Trotsky, who thrived in solitary confinement, Parvus found the isolation difficult to endure.[37] He was ultimately sentenced without trial to three years' banishment in Siberia. While on the journey to Turuchansk, near the Arctic Circle, he escaped with the help of fellow revolutionary Lev Deutsch. Disguised as a muzhik, he traveled back across Russia and crossed the border into Germany in November 1906.[38]

"Strategist without an army" (1907–1910)

[edit]Upon his return to Germany, Parvus was initially welcomed back into the SPD, his revolutionary credentials enhanced by his role in Russia. He published a popular account of his experiences, In the Russian Bastille during the Revolution, and resumed writing for the socialist press.[39] However, his intellectual partnership with Trotsky soon ended. While Trotsky developed the theory of permanent revolution to its radical conclusion—that a proletarian government in Russia must make deep inroads into capitalist property—Parvus drew back. He held to his concept of a "workers' democracy" as a modified phase of capitalist development, arguing that Russia was not yet ripe for socialism.[40]

Parvus's political standing in Germany was severely damaged by a financial scandal. In 1902, his publishing house had acquired the German rights to Maxim Gorky's play The Lower Depths. While the play was a sensational success, no royalties were ever paid to Gorky or to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, which was supposed to receive a share.[41] After the 1905 revolution, Gorky lodged a formal complaint with the SPD executive, accusing Parvus of embezzling some 130,000 marks. A party commission of inquiry found against Parvus, and though the verdict was never made public, he was privately warned not to seek editorial posts in the German socialist press. The affair permanently stained his reputation.[42]

Politically isolated and facing mounting personal difficulties, Parvus entered a period of intense theoretical work. He completed two major books, The State, Industry, and Socialism (1910) and The Class Struggle of the Proletariat (1911), which represented his last original contributions to socialist ideology.[43] He argued that the era of peaceful development was over and that capitalism's greatest danger was an impending world war, which could "be concluded only by a world revolution".[44] He also explored the practicalities of a post-revolutionary socialist economy, proposing the nationalization of banks as a first step and emphasizing the role of trade unions as a check on the power of the socialist state.[45] His ideas were largely ignored by his German comrades, who viewed them as utopian and his character as unstable.[46] His demoralization now complete, Parvus left Germany for Vienna in the summer of 1910, marking a turning point in his life.[47]

Ottoman Empire and World War I (1910–1917)

[edit]From Vienna, Parvus moved to Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire, where he lived for nearly five years.[48] During this period, he became a wealthy businessman. He established close connections with the ruling Young Turks and became the economic editor of their newspaper, Turk Yurdu. During the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), he was entrusted with providing supplies for the Turkish army and also dealt in grain and other commodities, laying the foundations of his fortune.[49]

When World War I broke out in 1914, Parvus saw it as the global catastrophe he had predicted and an opportunity to bring about the downfall of Tsarism. He advised the Turkish government to align with Germany and developed a grand strategy for a German victory in the East.[50] In January 1915, he presented a detailed plan to the German ambassador in Constantinople, Hans Freiherr von Wangenheim. The plan, titled "A preparation of the political mass strike in Russia", argued that the interests of the German government and the Russian revolutionaries were "identical".[51] He proposed a coordinated campaign of social revolution and nationalist separatism to bring about the "total destruction of Tsarism and the division of Russia into smaller states".[52]

Wangenheim recommended Parvus to Berlin, and in March 1915, he presented his plan at the German Foreign Ministry.[53] The German government, seeking a way to break the military stalemate, embraced the plan. Parvus received his first payment of one million marks for revolutionary work in Russia.[54] He established a base of operations in Copenhagen, Denmark, a neutral country that served as a clearing-house for trade and communication between the belligerent powers. From there, he built up a trading-cum-revolutionary network that mixed business with politics, using his commercial enterprise as a cover for channeling German funds and support to revolutionary groups inside Russia.[55] He also founded a new journal, Die Glocke (The Bell), to promote his political views among European socialists.[56] In May 1915, Parvus met with Lenin in Switzerland to persuade him to join the German-sponsored revolutionary front. Lenin, wary of Parvus's connections and suspicious of his motives, refused to cooperate.[57] Undeterred, Parvus proceeded to build his own independent organization, recruiting various Russian and Polish exiles. He planned and financed a general strike intended for 22 January 1916, the anniversary of Bloody Sunday. The strike was a failure, and the German Foreign Ministry subsequently reduced its support for his activities.[58]

Russian Revolution and "sealed train"

[edit]The February Revolution of 1917, which overthrew the Tsar, occurred spontaneously and took Parvus, like other revolutionaries, by surprise. It immediately revived German interest in his services.[59] Parvus recognized that the new Russian Provisional Government would continue the war and that the opportunity now existed to support the "extreme revolutionary movement" to bring about Russia's final collapse.[60]

His most significant contribution was arranging for the return of Lenin and other Bolshevik exiles from Switzerland to Russia. Cut off from his home country, Lenin was desperate to return, and Parvus's established network provided the means.[60] With the consent of the German General Staff, Parvus had his associate Jakob Fürstenberg (Hanecki) convey an offer to Lenin for transit across Germany.[61] After initial hesitation, Lenin and his group traveled in the famous "sealed train" in April 1917. Parvus waited for them in Stockholm, but Lenin, wary of being publicly compromised, refused to meet him personally. Instead, Parvus conferred with Lenin's trusted lieutenant Karl Radek, promising massive financial support for the Bolsheviks in their struggle for power.[62]

During the July Days, a failed Bolshevik uprising in Petrograd, the Provisional Government released documents purporting to prove that Lenin and the Bolsheviks were German agents, with Parvus named as the central intermediary. The evidence included financial telegrams between Parvus's network and Bolshevik representatives.[63] Lenin, in hiding, publicly denied any connection, while the Bolshevik Foreign Mission in Stockholm, led by Radek, issued a complex statement acknowledging business dealings but denying any political ties.[64]

After the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution, Parvus's role became even more contentious. He requested permission from Lenin to return to Russia, offering to serve the new Soviet government and defend his actions before a workers' court. In mid-December 1917, Radek returned from Petrograd with Lenin's answer: the request was refused, with the message that "the cause of the revolution should not be touched by dirty hands".[65] The rejection marked Parvus's final break with Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Feeling betrayed, he turned against them, launching a press campaign denouncing their dictatorial methods and their handling of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[66]

Later life and death (1918–1924)

[edit]The end of World War I and the German Revolution found Parvus isolated and passive. He had made a fortune from the war, engaging in large-scale trade, including a major coal deal between Germany and Denmark that gave him considerable political influence.[67] After the collapse of Imperial Germany, he traveled to Switzerland, intending to retire.[68] However, his reputation preceded him. The Swiss press accused him of being a Bolshevik agent and of leading a decadent lifestyle, calling him "le roi de Zürich". Amid a public scandal, he was arrested in January 1919 and subsequently expelled from the country in February 1920.[69]

Disenchanted, Parvus returned to Berlin and purchased a lavish 24-room mansion on the island of Schwanenwerder.[70] He lived in opulent style, hosting leaders of the Weimar Republic, including Friedrich Ebert and Philipp Scheidemann.[71] He continued his publishing activities, founding a new journal, Wiederaufbau (Reconstruction), which advocated for European economic cooperation and warned against a harsh peace treaty with Germany.[72] His health, however, was failing. After the collapse of the Wiederaufbau project in 1923, he largely withdrew from public life. Before his death, he married his secretary and is believed to have destroyed his personal papers.[73]

Alexander Parvus died of a heart attack at his home on Schwanenwerder on 12 December 1924. He was 57 years old.[74]

Legacy

[edit]Parvus remains one of the most enigmatic and controversial figures of 20th-century European socialism. His legacy was obscured for decades by a "conspiracy of silence" among former political associates and by vilification from both his enemies on the right and his former comrades on the left.[75] Nazi propaganda portrayed him as a key "November criminal" and a corrupting Jewish influence,[76] while Soviet and communist historiography branded him a traitor to the working class and a "socialist chauvinist".[77]

His pivotal role in the events leading to the Russian Revolution was only fully revealed after World War II with the opening of German Foreign Ministry archives, which documented his wartime activities.[78] Historians now recognize him as an original Marxist thinker whose theoretical work was of major importance, particularly his contributions to the theory of permanent revolution and his early analysis of imperialism and the world market.[79]

His life was a study in contradictions: a revolutionary theorist who became a millionaire businessman, an idealist who used the levers of great power politics, and an intellectual who sought to change the world but ended up isolated from all the major political movements of his time. He was, as his biographers Z. A. B. Zeman and W. B. Scharlau concluded, a new kind of political operator who "explored the exclusive avenues that connected the world of money with the world of politics".[80]

References

[edit]- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 10.

- ^ a b Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 11.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 14, 16.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 16.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 18.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 8.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 19.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 20.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 21.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 23.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 24.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 25.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 26.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 30, 32–33.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 32.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 35.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 47.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 51, 55.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 55.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 57.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 64.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 65.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 83.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 84.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 89.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 93.

- ^ a b Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 96.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 99.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 107.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 110.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 122–124.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 113.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 114.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 117.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 124.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 126.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 128.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 136.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 137.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 145.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 152.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 160, 164.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 168.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 158.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 187, 190.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 206.

- ^ a b Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 209.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 210.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 225.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 251.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 199–203.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 259.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 261, 266.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 1, 266.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 268.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 275.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 1, 275.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 2, 277.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 1, 20.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 2.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 3.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, pp. 113, 278.

- ^ Zeman & Scharlau 1965, p. 279.

Works cited

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Parvus Archive at marxists.org

- Karaömerlıoğlu, M. Asim (November 2004). "Helphand-Parvus and His Impact on Turkish Intellectual Life". Middle Eastern Studies. 40 (6): 145–165. doi:10.1080/0026320042000282928. JSTOR 4289957. S2CID 220377996.

- Pearson, Michael (1975). The Sealed Train: Journey to Revolution, Lenin – 1917. London: Macmillan.

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1922/feb/04.htm