Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

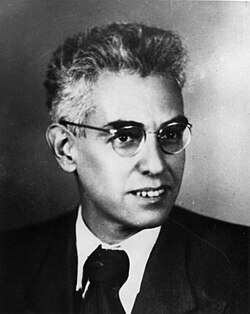

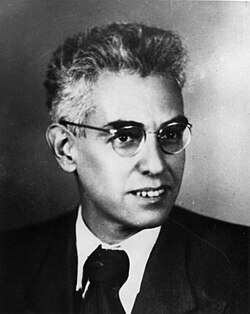

Alexander Luria

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

Alexander Romanovich Luria (/ˈlʊəriə/;[1] Russian: Алекса́ндр Рома́нович Лу́рия, IPA: [ˈlurʲɪjə]; 16 July 1902 – 14 August 1977) was a Soviet neuropsychologist, often credited as a father of modern neuropsychology. He developed an extensive and original battery of neuropsychological tests during his clinical work with brain-injured victims of World War II, which are still used in various forms. He made an in-depth analysis of the functioning of various brain regions and integrative processes of the brain in general. Luria's magnum opus, Higher Cortical Functions in Man (1962), is a much-used psychological textbook which has been translated into many languages and which he supplemented with The Working Brain in 1973.

It is less known that Luria's main interests, before the war, were in the field of cultural and developmental research in psychology. He became famous for his studies of low-educated populations of nomadic Uzbeks in the Uzbek SSR arguing that they demonstrate different (and lower) psychological performance from their contemporaries and compatriots under the economically more developed conditions of socialist collective farming (the kolkhoz). He was one of the founders of cultural-historical psychology and a colleague of Lev Vygotsky.[2][3] Apart from his work with Vygotsky, Luria is widely known for two extraordinary psychological case studies: The Mind of a Mnemonist, about Solomon Shereshevsky, who had highly advanced memory; and The Man with a Shattered World, about Lev Zasetsky, a man with a severe traumatic brain injury.

During his career Luria worked in a wide range of scientific fields at such institutions as the Academy of Communist Education (1920–1930s), Experimental Defectological Institute (1920–1930s, 1950–1960s, both in Moscow), Ukrainian Psychoneurological Academy (Kharkiv, early 1930s), All-Union Institute of Experimental Medicine, and the Burdenko Institute of Neurosurgery (late 1930s). A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Luria as the 69th most cited psychologist of the 20th century.

Life and career

[edit]Early life and childhood

[edit]Luria was born on 16 July 1902,[4] to Jewish parents in Kazan, a regional centre east of Moscow. Many of his family were in medicine. According to Luria's biographer Evgenia Homskaya, his father, Roman Albertovich Luria was a therapist who "worked as a professor at the University of Kazan; and after the Russian Revolution, he became a founder and chief of the Kazan Institute of Advanced Medical Education."[5][6] Two monographs of his father's writings were published in Russian under the titles, Stomach and Gullet Illnesses (1935) and Inside Look at Illness and Gastrogenic Diseases (1935).[7] His mother, Evgenia Viktorovna (née Khaskina), became a practicing dentist after finishing college in Poland. Luria was one of two children; his younger sister Lydia became a practicing psychiatrist.[8]

Early education and move to Moscow

[edit]Luria finished school ahead of schedule and completed his first degree in 1921 at Kazan State University. While still a student in Kazan, he established the Kazan Psychoanalytic Society and briefly exchanged letters with Sigmund Freud. Late in 1923, he moved to Moscow, where he lived on Arbat Street. His parents later followed him and settled down nearby. In Moscow, Luria was offered a position at the Moscow State Institute of Experimental Psychology, run from November 1923 by Konstantin Kornilov.

In 1924, Luria met Lev Vygotsky,[9] who would influence him greatly. The union of the two psychologists gave birth to what subsequently was termed the Vygotsky, or more precisely, the Vygotsky–Luria Circle. During the 1920s Luria also met a large number of scholars, including Aleksei Leontiev, Mark Lebedinsky, Alexander Zaporozhets, Bluma Zeigarnik, many of whom would remain his lifelong colleagues. Following Vygotsky and along with him, in mid-1920s Luria launched a project of developing a psychology of a radically new kind. This approach fused "cultural", "historical", and "instrumental" psychology and is most commonly referred to presently as cultural-historical psychology. It emphasizes the mediatory role of culture, particularly language, in the development of higher psychological functions in ontogeny and phylogeny.

Independently of Vygotsky, Luria developed the ingenious "combined motor method", which helped diagnose individuals' hidden or subdued emotional and thought processes. This research was published in the US in 1932 as The Nature of Human Conflicts and made him internationally famous as one of the leading psychologists in Soviet Russia. In 1937, Luria submitted the manuscript in Russian and defended it as a doctoral dissertation at the University of Tbilisi (not published in Russian until 2002).

Luria wrote three books during the 1920s after moving to Moscow, The Nature of Human Conflicts (in Russian, but during Luria's lifetime published only in English translation in 1932 in the US), Speech and Intellect in Child Development, and Speech and Intellect of Urban, Rural and Homeless Children (both in Russian). The second title came out in 1928, while the other two were published in the 1930s.

In early 1930s both Luria and Vygotsky started their medical studies in Kharkiv, then, after Vygotsky's death in 1934, Luria completed his medical education at 1st Moscow Medical Institute.

Multiculturalism and neurology

[edit]The 1930s were significant to Luria because his studies of indigenous people opened the field of multiculturalism to his general interests.[10] This interest would be revived in the later twentieth century by a variety of scholars and researchers who began studying and defending indigenous peoples throughout the world[citation needed]. Luria's work continued in this field with expeditions to Central Asia. Under the supervision of Vygotsky, Luria investigated various psychological changes (including perception, problem solving, and memory) that take place as a result of cultural development of undereducated minorities. In this regard he has been credited with a major contribution to the study of orality.[11]

In response to Lysenkoism's purge of geneticists,[12][13] Luria decided to pursue a physician degree, which he completed with honors in the summer of 1937. After rewriting and reorganizing his manuscript for The Nature of Human Conflicts, he defended it for a doctoral dissertation at the Institute of Tbilisi in 1937, and was appointed Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences. "At the age of thirty-four, he was one of the youngest professors of psychology in the country."[14] In 1933, Luria married Lana P. Lipchina, a well-known specialist in microbiology with a doctorate in the biological sciences.[15] The couple lived in Moscow on Frunze Street, where their only daughter Lena (Elena) was born.[15]

Luria also studied identical and fraternal twins in large residential schools to determine the interplay of various factors of cultural and genetic human development. In his early neuropsychological work in the end of the 1930s as well as throughout his postwar academic life he focused on the study of aphasia, focusing on the relation between language, thought, and cortical functions, particularly on the development of compensatory functions for aphasia.

World War II and aftermath

[edit]For Luria, the war with Germany that ended in 1945 resulted in a number of significant developments for the future of his career in neuropsychology. He was appointed Doctor of Medical Sciences in 1943 and Professor in 1944. Of specific importance for Luria was that he was assigned by the government to care for nearly 800 hospitalized patients with traumatic brain injury caused by the war.[16] Luria's treatment methods dealt with a wide range of emotional and intellectual dysfunctions.[16] He kept meticulous notes on these patients, and discerned from them three possibilities for functional recovery: "(1) disinhibition of a temporarily blocked function; (2) involvement of the vicarious potential of the opposite hemisphere; and (3) reorganization of the function system", which he described in a book titled Functional Recovery From Military Brain Wounds, (Moscow, 1948, Russian only.) A second book titled Traumatic Aphasia was written in 1947 in which "Luria formulated an original conception of the neural organization of speech and its disorders (aphasias) that differed significantly from the existing western conceptions about aphasia."[17] Soon after the end of the war, Luria was assigned a permanent position in General Psychology at the central Moscow State University in General Psychology, where he would predominantly stay for the remainder of his life; he was instrumental in the foundation of the Faculty of Psychology, and later headed the Departments of Patho- and Neuropsychology. By 1946, his father, the chief of the gastroenterological clinics at Botkin Hospital, had died of stomach cancer. His mother survived several more years, dying in 1950.[18]

1950s

[edit]Following the war, Luria continued his work in Moscow's Institute of Psychology. For a period of time he was removed from the Institute of Psychology, and in the 1950s he shifted to research on intellectually disabled children at the Defectological Institute. Here he did his most pioneering research in child psychology, and was able to permanently disassociate himself from the influence that was then still exerted in the Soviet Union by Pavlov's early research.[19] Luria said publicly that his own interests were limited to a specific examination of "Pavlov's second signal system" and did not concern Pavlov's simplified primary explanation of human behavior as based on a "conditioned reflex by means of positive reinforcement".[20] Luria's continued interest in the regulative function of speech was further revisited in the mid-1950s and was summarized in his 1957 monograph titled The Role of Speech in the Regulation of Normal and Abnormal Behavior. In this book Luria summarized his principal concerns in this field through three succinct points summarized by Homskaya as: "(1) the role of speech in the development of mental processes; (2) the development of the regulative function of speech; and (3) changes in the regulative functions of speech caused by various brain pathologies."[21]

Luria's main contributions to child psychology during the 1950s are well summarized by the research collected in a two-volume compendium of collected research published in Moscow in 1956 and 1958 under the title of Problems of Higher Nervous System Activity in Normal and Anomalous Children. Homskaya summarizes Luria's approach as centering on: "The application of the Method of Motor Associations (which) allowed investigators to reveal difficulties experienced by (unskilled) children in the process of forming conditioned links as well as restructuring and compensating by means of speech ... (Unskilled) children demonstrated acute dysfunction of the generalizing and regulating functions of speech."[22] Taking this direction, already by the mid-1950s, "Luria for the first time proposed his ideas about the differences of neurodynamic processes in different functional systems, primarily in verbal and motor systems."[23] Luria identified the three stages of language development in children in terms of "the formation of the mechanisms of voluntary actions: actions in the absence of a regulative verbal influence, actions with a nonspecific influence, and, finally, actions with a selective verbal influence."[21] For Luria, "The regulating function of speech thus appears as a main factor in the formation of voluntary behavior ... at first, the activating function is formed, and then the inhibitory, regulatory function."[24]

Cold War

[edit]In the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War, Luria's career expanded significantly with the publication of several new books. Of special note was the publication in 1962 of Higher Cortical Functions in Man and Their Impairment Caused by Local Brain Damage. The book has been translated into multiple foreign languages and has been recognized as the principal book establishing Neuropsychology as a medical discipline in its own right.[25] Previously, at the end of the 1950s, Luria's charismatic presence at international conferences had attracted almost worldwide attention to his research, which created a receptive medical audience for the book.

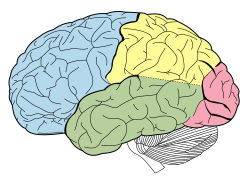

Luria's other books written or co-authored during the 1960s included: Higher Brain and Mental Processes (1963), The Neuropsychological Analysis of Problem Solving (1966, with L. S. Tzvetkova; English translation in 1990), Psychophysiology of the Frontal Lobes (first published in 1973), and Memory Disorders in Patients with Aneurysms of the Anterior Communicating Artery (co-authored with A. N. Konovalov and A. N. Podgoynaya). In studying memory disorders, Luria oriented his research to the distinction of long-term memory, short-term memory, and semantic memory. It was important for Luria to differentiate neuropsychological pathologies of memory from neuropsychological pathologies of intellectual operations.[26] These two types of pathology were often characterized by Luria as; "(1) the inability to make particular arithmetical operations while the general control of intellectual activity remained normal (predominantly occipital disturbances)... (2) the disability of general control over intellectual processes (predominantly frontal lobe disturbances."[27] Another of Luria's important book-length studies from the 1960s which would only be published in 1975 (and in English in 1976) was his well-received book titled Basic Problems of Neurolinguistics.

Late writings

[edit]Luria's productive rate of writing new books in neuropsychology remained largely undiminished during the 1970s and the last seven years of his life. Significantly, volume two of his Human Brain and Mental Processes appeared in 1970 under the title Neuropsychological Analysis of Conscious Activity, following the first volume from 1963 titled The Brain and Psychological Processes. The volume confirmed Luria's long sustained interest in studying the pathology of frontal lobe damage as compromising the seat of higher-order voluntary and intentional planning. Psychopathology of the Frontal Lobes, co-edited with Karl Pribram, was published in 1973.

Luria published his well-known book The Working Brain in 1973 as a concise adjunct volume to his 1962 book Higher Cortical Functions in Man. In this volume, Luria summarized his three-part global theory of the working brain as being composed of three constantly co-active processes, which he described as:

- the attentional (sensory-processing) system

- the mnestic-programming system

- the energetic maintenance system, with two levels: cortical and limbic

This model was later used as a structure of the Functional Ensemble of Temperament model matching functionality of neurotransmitter systems. The two books together are considered by Homskaya as "among Luria's major works in neuropsychology, most fully reflecting all the aspects (theoretical, clinical, experimental) of this new discipline."[28]

Among his late writings are also two extended case studies directed toward the popular press and a general readership, in which he presented some of the results of major advances in the field of clinical neuropsychology. These two books are among his most popular writings. According to Oliver Sacks, in these works "science became poetry".[29]

- In The Mind of a Mnemonist (1968), Luria studied Solomon Shereshevsky, a Russian journalist with a seemingly unlimited memory, sometimes referred to in contemporary literature as "flashbulb" memory, in part due to his fivefold synesthesia.

- In The Man with the Shattered World (1971) he documented the recovery under his treatment of the soldier Lev Zasetsky, who had experienced a brain wound in World War II.

In 1974 and 1976, Luria presented successively his two-volume research study titled The Neuropsychology of Memory. The first volume was titled Memory Dysfunctions Caused by Local Brain Damage and the second Memory Dysfunctions Caused by Damage to Deep Cerebral Structures. Luria's book written in the 1960s titled Basic Problems of Neurolinguistics was finally published in 1975, and was matched by his last book, Language and Cognition, published posthumously in 1980. Luria's last co-edited book, with Homskaya, was titled Problems of Neuropsychology and appeared in 1977.[30] In it, Luria was critical of simplistic models of behaviorism and indicated his preference for the position of "Anokhin's concept of 'functional systems,' in which the reflex arc is substituted by the notion of a 'reflex ring' with a feedback loop."[31] In this approach, the classical physiology of reflexes was to be downplayed while the "physiology of activity" as described by Bernshtein was to be emphasized concerning the active character of human active functioning.[31]

Luria's death is recorded by Homskaya in the following words: "On June 1, 1977, the All-Union Psychological Congress started its work in Moscow. As its organizer, Luria introduced the section on neuropsychology. The next day's meeting, however, he was not able to attend. His wife Lana Pimenovna, who was extremely sick, had an operation on June 2. During the following two and a half months of his life, Luria did everything possible to save or at least to soothe his wife. Not being able to comply with this task, he died of a myocardial infarction on August 14. His funeral was attended by an endless number of people – psychologists, teachers, doctors, and just friends. His wife died six months later."[32]

Main areas of research

[edit]In her biography of Luria, Homskaya summarized the six main areas of Luria's research over his lifetime in accordance with the following outline: (1) The Socio-historical Determination of the Human Psyche, (2) The Biological (Genetic) Determination of the Human Psyche, (3) Higher Psychological Functions Mediated by Signs-Symbols; The Verbal System as the Main System of Signs (along with Luria's well-known three-part differentiation of it), (4) The Systematic Organization of Psychological Functions and Consciousness (along with Luria's well-known four-part outline of this), (5) Cerebral Mechanisms of the Mind (Brain and Psyche); Links between Psychology and Physiology, and (6) The Relationship between Theory and Practice.[33]

A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Luria as the 69th most cited psychologist of the 20th century.[34]

Principal research trends

[edit]As examples of the vigorous growth of new research related to Luria's original research during his own lifetime are the fields of linguistic aphasia, anterior lobe pathology, speech dysfunction, and child neuropsychology.

Linguistic aphasia

[edit]Luria's neuropsychological theory of language and speech distinguished clearly between the phases that separate inner language within the individual consciousness and spoken language intended for communication between individuals intersubjectively. It was of special significance for Luria not only to distinguish the sequential phases required to get from inner language to serial speech, but also to emphasize the difference of encoding of subjective inner thought as it develops into intersubjective speech. This was in contrast to the decoding of spoken speech as it is communicated from other individuals and decoded into subjectively understood inner language.[35] In the case of the encoding of inner language, Luria expressed these successive phases as moving first from inner language to semantic set representations, then to deep semantic structures, then to deep syntactic structures, then to serial surface speech. For the encoding of serial speech, the phases remained the same, though the decoding was oriented in the opposite direction of transitions between the distinct phases.[35]

Frontal (anterior) lobes

[edit]Luria's studies of the frontal lobes were concentrated in five principal areas: (1) attention, (2) memory, (3) intellectual activity, (4) emotional reactions, and (5) voluntary movements. Luria's main books for investigation of these functions of the frontal lobes are titled The Frontal Lobes,[36] Problems of Neuropsychology (1977), Functions of the Frontal Lobes (1982, posthumously published), Higher Cortical Functions in Man(1962) and Restoration of Function After Brain Injury (1963). [37]

Luria was first to identify the fundamental role of the frontal lobes in sustained attention, flexibility of behaviour, and self-organization. Based on his clinical observations and rehabilitation practice, he suggested that different areas of the frontal lobes differentially regulate these three aspects of behaviour. This suggestion was later supported by the neuroscience investigating frontal lobes. Practically all modern neuropsychological tests for frontal lobes damage have some components that were offered by Luria in his assessment and rehabilitation practice.

Speech dysfunction

[edit]Luria's research on speech dysfunction was principally in the areas of (1) expressive speech, (2) impressive speech, (3) memory, (4) intellectual activity, and (5) personality.[38]

Child neuropsychology

[edit]This field was formed largely based upon Luria's books and writings on neuropsychology integrated during his experiences during the war years and later periods. In the area of child neuropsychology, "The need for its creation was dictated by the fact that children with localized brain damage were found to reveal specific different features of dissolution of psychological functions. Under Luria's supervision, his colleague Simernitskaya began to study nonverbal (visual-spatial) and verbal functions, and demonstrated that damage to the left and right hemispheres provoked different types of dysfunctions in children than in adults. This study initiated a number of systematic investigations concerning changes in the localization of higher psychological functions during the process of development."[39] Luria's general research was mostly centered on the treatment and rehabilitation "of speech, and observations concerning direct and spontaneous rehabilitation were generalized."[39] Other areas involving "Luria's works have made a significant contribution in the sphere of rehabilitation of expressive and impressive speech (Tzvetkova, 1972), 1985), memory (Krotkova, 1982), intellectual activity (Tzvetkova, 1975), and personality (Glozman, 1987) in patients with localized brain damage."[39]

Luria-Nebraska neuropsychological test

[edit]The Luria-Nebraska is a standardized test based on Luria's theories regarding neuropsychological functioning. Luria was not part of the team that originally standardized this test; he was only indirectly referenced by other researchers as a scholar who had published relevant results in the field of neuropsychology. Anecdotally, when Luria first had the battery described to him he commented that he had expected that someone would eventually do something like this with his original research.

Books

[edit]- Luria, A.R. The Nature of Human Conflicts – or Emotion, Conflict, and Will: An Objective Study of Disorganisation and Control of Human Behaviour. New York: Liveright Publishers, 1932.

- Luria, A.R.Higher Cortical Functions in Man. Moscow University Press, 1962. Library of Congress Number: 65-11340.

- Luria, A.R. (1963). Restoration of Function After Brain Injury. Pergamon Press.

- Luria, A.R. (1966). Human Brain and Psychological Processes. Harper & Row.

- Luria, A.R. (1970). Traumatic Aphasia: Its Syndromes, Psychology, and Treatment. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-0717-2. Summary at BrainInfo

- The Working Brain. Basic Books. 1973. ISBN 978-0-465-09208-6.

- Luria, A.R. (1976). The Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-13731-8.

- Luria, A.R. (1968). The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book About A Vast Memory. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-57622-3.

- (With Solotaroff, Lynn) The Man with a Shattered World: The History of a Brain Wound, Harvard University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-674-54625-3.

- Autobiography of Alexander Luria: A Dialogue with the Making of Mind. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. 2005. ISBN 978-0-8058-5499-2.

In cinema

[edit]- Paolo Rosa's film Il mnemonista (2000) is based on his book The Mind of a Mnemonist.

- Chris Doyle's auteur film Away with Words is largely inspired by Luria's The Mind of a Mnemonist.

- Jacqueline Goss's 28-minute feature How to Fix the World (2004) is a digitally animated lighthearted parody that "draws from Luria's study of how the introduction of literacy affected the thought-patterns of Central Asian peasants"—description taken from the cover of the DVD Wendy and Lucy (2008), OSC-004, which includes it as an independent supplement to the unrelated feature film. Educational parody. Full 28-minute film is viewable at Vimeo.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Luria". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Yasnitsky, A., & R. van der Veer (eds) (2015). Revisionist Revolution in Vygotsky Studies Archived 6 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. London and New York: Routledge

- ^ Yasnitsky, A., R. van der Veer, E. Aguilar, & L. N. García (eds) (2016). Vygotski revisitado: una historia crítica de su contexto y legado. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila Editores.

- ^ "On This Day in 1902 Alexander Luria Was Born". The Moscow Times. 16 July 2019.

- ^ Evgenia Homskaya (2001). Alexander Romanovich Luria: A Scientific Biography, Plenum Publishers, New York, NY, p. 9.

- ^ Kostyanaya, Maria; Rossouw, Pieter (9 October 2013). "Alexander Luria: Life, research & contribution to neuroscience". The Neuropsychotherapist. 1 (2): 47–55. doi:10.12744/ijnpt.2013.0047-0055.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 9.

- ^ Homskaya, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Yasnitsky, A. (2018). Vygotsky: An Intellectual Biography. London and New York: Routledge BOOK PREVIEW

- ^ Homskaya, p. 25.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (2002). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 49–54. ISBN 978-0-415-28129-4.

- ^ Ing, Simon (21 February 2017). Stalin and the Scientists: A History of Triumph and Tragedy, 1905-1953. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-8986-8. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

citing the memoir of Luria's daughter Elena Alexandrovna, 'I was accused of all mortal sins, right down to racism, and I was forced to leave the Institute of Psychology.'

- ^ "LURIA, ALEXANDER ROMANOVICH". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 31.

- ^ a b Homskaya, p. 33.

- ^ a b Homskaya, p. 36.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 38.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 39.

- ^ Homskaya, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 42.

- ^ a b Homskaya, p. 48.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 46.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 45.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 47.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 55.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 61.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 62.

- ^ Homskaya, pp. 70-71.

- ^ Michiko Kakutani, "Oliver Sacks, Casting Light on the Interconnectedness of Life", The New York Times, 30 August 2015.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 77.

- ^ a b Homskaya, p. 79.

- ^ Homskaya, p. 82.

- ^ Homskaya, Chapter VIII, pp. 82–101.

- ^ Haggbloom, Steven J.; Warnick, Renee; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; et al. (2002). "The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.586.1913. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139. S2CID 145668721.

- ^ a b Luria, Alexander. Neuropsychology of Neurolinguistics.

- ^ Luria, A.R. (1966). Human Brain and Psychological Processes. Harper & Row.

- ^ Luria, A.R. (1963). Restoration of Function After Brain Injury. Pergamon Press.

- ^ Homskaya, closing chapter.

- ^ a b c Homskaya, p. 108.

Sources

[edit]- Proctor, H. (2020). Psychologies in Revolution: Alexander Luria's 'Romantic Science' and Soviet Social History. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yasnitsky, A. (Ed.) (2019). Questioning Vygotsky's Legacy: Scientific Psychology or Heroic Cult. London and New York: Routledge – book preview

- Yasnitsky, A. (2018). Vygotsky: An Intellectual Biography. London, Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13-8806740 – book preview

- Yasnitsky, A., van der Veer, R., Aguilar, E. & García, L.N. (Eds.) (2016). Vygotski revisitado: una historia crítica de su contexto y legado. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila Editores

- Yasnitsky, A. & van der Veer, R. (Eds.) (2016). Revisionist Revolution in Vygotsky Studies. Routledge, ISBN 978-1-13-888730-5

- Proctor, H. (2016). Revolutionary thinking: a theoretical history of Alexander Luria's 'Romantic science'. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London

- Yasnitsky, A. (2011). Vygotsky Circle as a Personal Network of Scholars: Restoring Connections Between People and Ideas. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, doi:10.1007/s12124-011-9168-5.

- Mecacci, L. (December 2005). "Luria: A unitary view of human brain and mind". Cortex. 41 (6): 816–822. doi:10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70300-9. PMID 16350662. S2CID 4478127.

- Homskaya, E. (2001). Alexander Romanovich Luria: A Scientific Biography, New York, NY: Plenum Publishers, ISBN 978-0-3064-6494-2.

- Michael Cole, Karl Levitin, Alexander R. Luria (2014). The Autobiography of Alexander Luria: A Dialogue with The Making of Mind. Psychology Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-3177-5928-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- A.R Luria Archive at marxists.org

- A.R. Luria Archive @ Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition at lchc.ucsd.edu

- A Small Book About a Big Memory – Translation by Ivan Samokish" A free translation from the original Russian available in PDF format.

- Alexander Luria – The Mind of a Mnemonist Jerome Brunner 1987 Harvard University Press

- Luria's Areas of the Human Cortex Involved in Language. Illustrated summary of Luria's book Traumatic Aphasia.

- Luria publication list, (pages 9–51 of the pdf) and more at Springer page for Evgenia D. Homskaya's biography