Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anabolism

View on Wikipedia

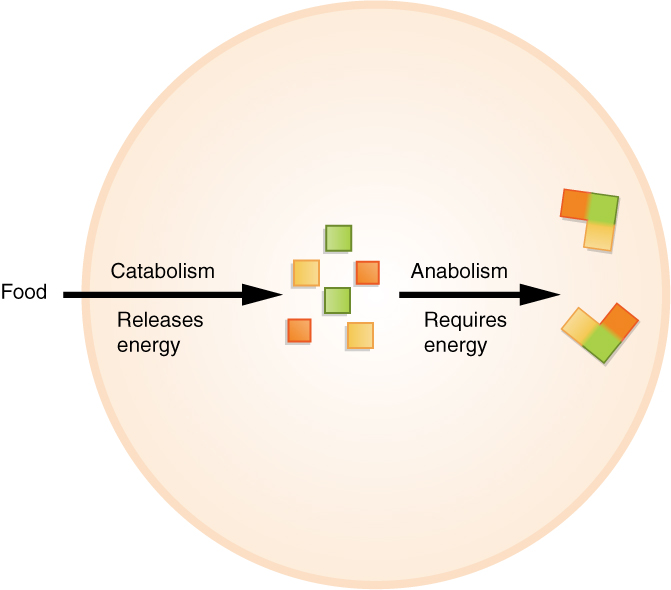

Anabolism (/əˈnæbəlɪzəm/ ə-NAB-ə-liz-əm)[1] is the set of metabolic pathways that construct macromolecules like DNA or RNA from smaller units.[2][3] These reactions require energy, known also as an endergonic process.[4] Anabolism is the building-up aspect of metabolism, whereas catabolism is the breaking-down aspect. Anabolism is usually synonymous with biosynthesis.

Pathway

[edit]Polymerization, an anabolic pathway used to build macromolecules such as nucleic acids, proteins, and polysaccharides, uses condensation reactions to join monomers.[5] Macromolecules are created from smaller molecules using enzymes and cofactors.

Energy source

[edit]Anabolism is powered by catabolism, where large molecules are broken down into smaller parts and then used up in cellular respiration. Many anabolic processes are powered by the cleavage of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).[6] Anabolism usually involves reduction and decreases entropy, making it unfavorable without energy input.[7] The starting materials, called the precursor molecules, are joined using the chemical energy made available from hydrolyzing ATP, reducing the cofactors NAD+, NADP+, and FAD, or performing other favorable side reactions.[8] Occasionally it can also be driven by entropy without energy input, in cases like the formation of the phospholipid bilayer of a cell, where hydrophobic interactions aggregate the molecules.[9]

Cofactors

[edit]The reducing agents NADH, NADPH, and FADH2,[10] as well as metal ions,[5] act as cofactors at various steps in anabolic pathways. NADH, NADPH, and FADH2 act as electron carriers, while charged metal ions within enzymes stabilize charged functional groups on substrates.

Substrates

[edit]Substrates for anabolism are mostly intermediates taken from catabolic pathways during periods of high energy charge in the cell.[11]

Functions

[edit]Anabolic processes build organs and tissues. These processes produce growth and differentiation of cells and increase in body size, a process that involves synthesis of complex molecules. Examples of anabolic processes include the growth and mineralization of bone and increases in muscle mass.

Anabolic hormones

[edit]Endocrinologists have traditionally classified hormones as anabolic or catabolic, depending on which part of metabolism they stimulate. The classic anabolic hormones are the anabolic steroids, which stimulate protein synthesis and muscle growth, and especially insulin, which is the main anabolic hormone of the body,[12] regulating the metabolism of protein, carbohydrates, and fats.[13]

Photosynthetic carbohydrate synthesis

[edit]Photosynthetic carbohydrate synthesis in plants and certain bacteria is an anabolic process that produces glucose, cellulose, starch, lipids, and proteins from CO2.[7] It uses the energy produced from the light-driven reactions of photosynthesis, and creates the precursors to these large molecules via carbon assimilation in the photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle, a.k.a. the Calvin cycle.[11]

Amino acid biosynthesis

[edit]All amino acids are formed from intermediates in the catabolic processes of glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, or the pentose phosphate pathway. From glycolysis, glucose 6-phosphate is a precursor for histidine; 3-phosphoglycerate is a precursor for glycine and cysteine; phosphoenol pyruvate, combined with the 3-phosphoglycerate-derivative erythrose 4-phosphate, forms tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine; and pyruvate is a precursor for alanine, valine, leucine, and isoleucine. From the citric acid cycle, α-ketoglutarate is converted into glutamate and subsequently glutamine, proline, and arginine; and oxaloacetate is converted into aspartate and subsequently asparagine, methionine, threonine, and lysine.[11]

Glycogen storage

[edit]During periods of high blood sugar, glucose 6-phosphate from glycolysis is diverted to the glycogen-storing pathway. It is changed to glucose-1-phosphate by phosphoglucomutase and then to UDP-glucose by UTP--glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase. Glycogen synthase adds this UDP-glucose to a glycogen chain.[11]

Gluconeogenesis

[edit]Glucagon is traditionally a catabolic hormone, but also stimulates the anabolic process of gluconeogenesis by the liver, and to a lesser extent the kidney cortex and intestines, during starvation to prevent low blood sugar.[10] It is the process of converting pyruvate into glucose. Pyruvate can come from the breakdown of glucose, lactate, amino acids, or glycerol.[14] The gluconeogenesis pathway has many reversible enzymatic processes in common with glycolysis, but it is not the process of glycolysis in reverse. It uses different irreversible enzymes to ensure the overall pathway runs in one direction only.[14]

Regulation

[edit]Anabolism operates with separate enzymes from catalysis, which undergo irreversible steps at some point in their pathways. This allows the cell to regulate the rate of production and prevent an infinite loop, also known as a futile cycle, from forming with catabolism.[11]

The balance between anabolism and catabolism is sensitive to ADP and ATP, otherwise known as the energy charge of the cell. High amounts of ATP cause cells to favor the anabolic pathway and slow catabolic activity, while excess ADP slows anabolism and favors catabolism.[11] These pathways are also regulated by circadian rhythms, with processes such as glycolysis fluctuating to match an animal's normal periods of activity throughout the day.[15]

Etymology

[edit]The word anabolism is from Neo-Latin, with roots from Ancient Greek: ἀνά, "upward" and βάλλειν, "to throw".

References

[edit]- ^ "anabolism". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Shimizu, Kazuyuki (2013). "Main metabolism". Bacterial Cellular Metabolic Systems. Elsevier. p. 1–54. doi:10.1533/9781908818201.1. ISBN 978-1-907568-01-5.

- ^ de Bolster MW (1997). "Glossary of Terms Used in Bioinorganic Chemistry: Anabolism". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, Choi J, Avissar Y (2013). Biology. Rice University, Houston Texas: OpenStax. ISBN 978-1-938168-09-3.

- ^ a b Alberts B, Johnson A, Julian L, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (5th ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 2018-11-01. Alt URL

- ^ Nicholls DG, Ferguson SJ (2002). Bioenergetics (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-518121-1.

- ^ a b Ahern K, Rajagopal I (2013). Biochemistry Free and Easy (PDF) (2nd ed.). Oregon State University.

- ^ Voet D, Voet JG, Pratt CW (2013). Fundamentals of biochemistry : life at the molecular level (Fourth ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-54784-7. OCLC 738349533.

- ^ Hanin I, Pepeu G (2013-11-11). Phospholipids: biochemical, pharmaceutical, and analytical considerations. New York. ISBN 978-1-4757-1364-0. OCLC 885405600.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Jakubowski H (2002). "An Overview of Metabolic Pathways - Anabolism". Biochemistry Online. College of St. Benedict, St. John's University: LibreTexts.

- ^ a b c d e f Nelson DL, Lehninger AL, Cox MM (2013). Principles of Biochemistry. New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-3414-6.

- ^ Voet D, Voet JG (2011). Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: Wiley.

- ^ Stryer L (1995). Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 773–74. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- ^ a b Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L (2002). Biochemistry (5th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3051-4. OCLC 48055706.

- ^ Ramsey KM, Marcheva B, Kohsaka A, Bass J (2007). "The clockwork of metabolism". Annual Review of Nutrition. 27: 219–40. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093546. PMID 17430084.