Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Endocrinology

View on Wikipedia Illustration depicting the primary endocrine organs of a female | |

| System | Endocrine |

|---|---|

| Significant diseases | Diabetes, Thyroid disease, Androgen excess |

| Significant tests | Thyroid function tests, Blood sugar levels |

| Specialist | Endocrinologist |

| Glossary | Glossary of medicine |

Endocrinology (from endocrine + -ology) is a branch of biology and medicine dealing with the endocrine system, its diseases, and its specific secretions known as hormones. It is also concerned with the integration of developmental events proliferation, growth, and differentiation, and the psychological or behavioral activities of metabolism, growth and development, tissue function, sleep, digestion, respiration, excretion, mood, stress, lactation, movement, reproduction, and sensory perception caused by hormones. Specializations include behavioral endocrinology and comparative endocrinology.[1]

The endocrine system consists of several glands, all in different parts of the body, that secrete hormones directly into the blood rather than into a duct system. Therefore, endocrine glands are regarded as ductless glands. Hormones have many different functions and modes of action; one hormone may have several effects on different target organs, and, conversely, one target organ may be affected by more than one hormone.

The endocrine system

[edit]Endocrinology is the study of the endocrine system in the human body.[2] This is a system of glands which secrete hormones. Hormones are chemicals that affect the actions of different organ systems in the body. Examples include thyroid hormone, growth hormone, and insulin. The endocrine system involves a number of feedback mechanisms, so that often one hormone (such as thyroid stimulating hormone) will control the action or release of another secondary hormone (such as thyroid hormone). If there is too much of the secondary hormone, it may provide negative feedback to the primary hormone, maintaining homeostasis.[3][4][5]

In the original 1902 definition by Bayliss and Starling (see below), they specified that, to be classified as a hormone, a chemical must be produced by an organ, be released (in small amounts) into the blood, and be transported by the blood to a distant organ to exert its specific function. This definition holds for most "classical" hormones, but there are also paracrine mechanisms (chemical communication between cells within a tissue or organ), autocrine signals (a chemical that acts on the same cell), and intracrine signals (a chemical that acts within the same cell).[6] A neuroendocrine signal is a "classical" hormone that is released into the blood by a neurosecretory neuron (see article on neuroendocrinology).[citation needed]

Hormones

[edit]Griffin and Ojeda identify three different classes of hormones based on their chemical composition:[7]

Amines

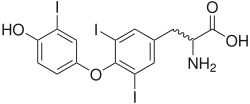

[edit]Amines, such as norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine (catecholamines), are derived from single amino acids, in this case tyrosine. Thyroid hormones such as 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine (T3) and 3,5,3',5'-tetraiodothyronine (thyroxine, T4) make up a subset of this class because they derive from the combination of two iodinated tyrosine amino acid residues.[8]

Peptide and protein

[edit]Peptide hormones and protein hormones consist of three (in the case of thyrotropin-releasing hormone) to more than 200 (in the case of follicle-stimulating hormone) amino acid residues and can have a molecular mass as large as 31,000 grams per mole. All hormones secreted by the pituitary gland are peptide hormones, as are leptin from adipocytes, ghrelin from the stomach, and insulin from the pancreas.[citation needed]

Steroid

[edit]Steroid hormones are converted from their parent compound, cholesterol. Mammalian steroid hormones can be grouped into five groups by the receptors to which they bind: glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, androgens, estrogens, and progestogens. Some forms of vitamin D, such as calcitriol, are steroid-like and bind to homologous receptors, but lack the characteristic fused ring structure of true steroids.

As a profession

[edit]| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Doctor, Medical specialist |

Occupation type | Specialty |

Activity sectors | Medicine |

| Description | |

Education required |

|

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Clinics |

Although every organ system secretes and responds to hormones (including the brain, lungs, heart, intestine, skin, and the kidneys), the clinical specialty of endocrinology focuses primarily on the endocrine organs, meaning the organs whose primary function is hormone secretion. These organs include the pituitary, thyroid, adrenals, ovaries, testes, and pancreas.

An endocrinologist is a physician who specializes in treating disorders of the endocrine system, such as diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and many others (see list of diseases).

Work

[edit]The medical specialty of endocrinology involves the diagnostic evaluation of a wide variety of symptoms and variations and the long-term management of disorders of deficiency or excess of one or more hormones.[9]

The diagnosis and treatment of endocrine diseases are guided by laboratory tests to a greater extent than for most specialties. Many diseases are investigated through excitation/stimulation or inhibition/suppression testing. This might involve injection with a stimulating agent to test the function of an endocrine organ. Blood is then sampled to assess the changes of the relevant hormones or metabolites. An endocrinologist needs extensive knowledge of clinical chemistry and biochemistry to understand the uses and limitations of the investigations.

A second important aspect of the practice of endocrinology is distinguishing human variation from disease. Atypical patterns of physical development and abnormal test results must be assessed as indicative of disease or not. Diagnostic imaging of endocrine organs may reveal incidental findings called incidentalomas, which may or may not represent disease.[10]

Endocrinology involves caring for the person as well as the disease. Most endocrine disorders are chronic diseases that need lifelong care. Some of the most common endocrine diseases include diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and the metabolic syndrome. Care of diabetes, obesity and other chronic diseases necessitates understanding the patient at the personal and social level as well as the molecular, and the physician–patient relationship can be an important therapeutic process.

Apart from treating patients, many endocrinologists are involved in clinical science and medical research, teaching, and hospital management.

Training

[edit]Endocrinologists are specialists of internal medicine or pediatrics. Reproductive endocrinologists deal primarily with problems of fertility and menstrual function—often training first in obstetrics. Most qualify as an internist, pediatrician, or gynecologist for a few years before specializing, depending on the local training system. In the U.S. and Canada, training for board certification in internal medicine, pediatrics, or gynecology after medical school is called residency. Further formal training to subspecialize in adult, pediatric, or reproductive endocrinology is called a fellowship. Typical training for a North American endocrinologist involves 4 years of college, 4 years of medical school, 3 years of residency, and 2 years of fellowship. In the US, adult endocrinologists are board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) or the American Osteopathic Board of Internal Medicine (AOBIM) in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism.[citation needed]

Diseases treated by endocrinologists

[edit]- Diabetes mellitus: This is a chronic condition that affects how your body regulates blood sugar. There are two main types: type 1 diabetes, which is an autoimmune disease that occurs when the body attacks the cells that produce insulin, and type 2 diabetes, which is a condition in which the body either doesn't produce enough insulin or doesn't use it effectively.[11]

- Thyroid disorders: These are conditions that affect the thyroid gland, a butterfly-shaped gland located in the front of your neck. The thyroid gland produces hormones that regulate your metabolism, heart rate, and body temperature. Common thyroid disorders include hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) and hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid).

- Adrenal disorders: The adrenal glands are located on top of your kidneys. They produce hormones that help regulate blood pressure, blood sugar, and the body's response to stress. Common adrenal disorders include Cushing syndrome (excess cortisol production) and Addison's disease (adrenal insufficiency).

- Pituitary disorders: The pituitary gland is a pea-sized gland located at the base of the brain. It produces hormones that control many other hormone-producing glands in the body. Common pituitary disorders include acromegaly (excess growth hormone production) and Cushing's disease (excess ACTH production).

- Metabolic disorders: These are conditions that affect how your body processes food into energy. Common metabolic disorders include obesity, high cholesterol, and gout.

- Calcium and bone disorders: Endocrinologists also treat conditions that affect calcium levels in the blood, such as hyperparathyroidism (too much parathyroid hormone) and osteoporosis (weak bones).

- Sexual and reproductive disorders: Endocrinologists can also help diagnose and treat hormonal problems that affect sexual development and function, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and erectile dysfunction.

- Endocrine cancers: These are cancers that develop in the endocrine glands. Endocrinologists can help diagnose and treat these cancers.

Diseases and medicine

[edit]Diseases

[edit]- See main article at Endocrine diseases

Endocrinology also involves the study of the diseases of the endocrine system. These diseases may relate to too little or too much secretion of a hormone, too little or too much action of a hormone, or problems with receiving the hormone.

Societies and Organizations

[edit]Because endocrinology encompasses so many conditions and diseases, there are many organizations that provide education to patients and the public. The Hormone Foundation is the public education affiliate of The Endocrine Society and provides information on all endocrine-related conditions. Other educational organizations that focus on one or more endocrine-related conditions include the American Diabetes Association, Human Growth Foundation, American Menopause Foundation, Inc., and American Thyroid Association.[12][13]

In North America the principal professional organizations of endocrinologists include The Endocrine Society,[14] the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists,[15] the American Diabetes Association,[16] the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society,[17] and the American Thyroid Association.[18]

In Europe, the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (ESPE) are the main organisations representing professionals in the fields of adult and paediatric endocrinology, respectively.

In the United Kingdom, the Society for Endocrinology[19] and the British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes[20] are the main professional organisations.

The European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology[21] is the largest international professional association dedicated solely to paediatric endocrinology. There are numerous similar associations around the world.

History

[edit]

The earliest study of endocrinology began in China.[22] The Chinese were isolating sex and pituitary hormones from human urine and using them for medicinal purposes by 200 BC.[22] They used many complex methods, such as sublimation of steroid hormones.[22] Another method specified by Chinese texts—the earliest dating to 1110—specified the use of saponin (from the beans of Gleditsia sinensis) to extract hormones, but gypsum (containing calcium sulfate) was also known to have been used.[22]

Although most of the relevant tissues and endocrine glands had been identified by early anatomists, a more humoral approach to understanding biological function and disease was favoured by the ancient Greek and Roman thinkers such as Aristotle, Hippocrates, Lucretius, Celsus, and Galen, according to Freeman et al.,[23] and these theories held sway until the advent of germ theory, physiology, and organ basis of pathology in the 19th century.

In 1849, Arnold Berthold noted that castrated cockerels did not develop combs and wattles or exhibit overtly male behaviour.[24] He found that replacement of testes back into the abdominal cavity of the same bird or another castrated bird resulted in normal behavioural and morphological development, and he concluded (erroneously) that the testes secreted a substance that "conditioned" the blood that, in turn, acted on the body of the cockerel. In fact, one of two other things could have been true: that the testes modified or activated a constituent of the blood or that the testes removed an inhibitory factor from the blood. It was not proven that the testes released a substance that engenders male characteristics until it was shown that the extract of testes could replace their function in castrated animals. Pure, crystalline testosterone was isolated in 1935.[25]

Graves' disease was named after Irish doctor Robert James Graves,[26] who described a case of goiter with exophthalmos in 1835. The German Karl Adolph von Basedow also independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840, while earlier reports of the disease were also published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajani and Antonio Giuseppe Testa, in 1802 and 1810 respectively,[27] and by the English physician Caleb Hillier Parry (a friend of Edward Jenner) in the late 18th century.[28] Thomas Addison was first to describe Addison's disease in 1849.[29]

In 1902 William Bayliss and Ernest Starling performed an experiment in which they observed that acid instilled into the duodenum caused the pancreas to begin secretion, even after they had removed all nervous connections between the two.[30] The same response could be produced by injecting extract of jejunum mucosa into the jugular vein, showing that some factor in the mucosa was responsible. They named this substance "secretin" and coined the term hormone for chemicals that act in this way.

Joseph von Mering and Oskar Minkowski made the observation in 1889 that removing the pancreas surgically led to an increase in blood sugar, followed by a coma and eventual death—symptoms of diabetes mellitus. In 1922, Banting and Best realized that homogenizing the pancreas and injecting the derived extract reversed this condition.[31]

Neurohormones were first identified by Otto Loewi in 1921.[32] He incubated a frog's heart (innervated with its vagus nerve attached) in a saline bath, and left in the solution for some time. The solution was then used to bathe a non-innervated second heart. If the vagus nerve on the first heart was stimulated, negative inotropic (beat amplitude) and chronotropic (beat rate) activity were seen in both hearts. This did not occur in either heart if the vagus nerve was not stimulated. The vagus nerve was adding something to the saline solution. The effect could be blocked using atropine, a known inhibitor to heart vagal nerve stimulation. Clearly, something was being secreted by the vagus nerve and affecting the heart. The "vagusstuff" (as Loewi called it) causing the myotropic (muscle enhancing) effects was later identified to be acetylcholine and norepinephrine. Loewi won the Nobel Prize for his discovery.

Recent work in endocrinology focuses on the molecular mechanisms responsible for triggering the effects of hormones. The first example of such work being done was in 1962 by Earl Sutherland. Sutherland investigated whether hormones enter cells to evoke action, or stayed outside of cells. He studied norepinephrine, which acts on the liver to convert glycogen into glucose via the activation of the phosphorylase enzyme. He homogenized the liver into a membrane fraction and soluble fraction (phosphorylase is soluble), added norepinephrine to the membrane fraction, extracted its soluble products, and added them to the first soluble fraction. Phosphorylase activated, indicating that norepinephrine's target receptor was on the cell membrane, not located intracellularly. He later identified the compound as cyclic AMP (cAMP) and with his discovery created the concept of second-messenger-mediated pathways. He, like Loewi, won the Nobel Prize for his groundbreaking work in endocrinology.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Al-hussaniy, Hany; AL-Biati, Haedar A (2022-10-12). "The Role of Leptin Hormone, Neuropeptide Y, Ghrelin and Leptin/Ghrelin ratio in Obesogenesis". Medical and Pharmaceutical Journal. 1 (2): 12–23. doi:10.55940/medphar20227. ISSN 2957-6067.

- ^ "Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Specialty Description". American Medical Association. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Carroll, Robert G. (2007-01-01), Carroll, Robert G. (ed.), "13 - Endocrine System", Elsevier's Integrated Physiology, Philadelphia: Mosby, pp. 157–176, ISBN 978-0-323-04318-2, retrieved 2023-11-15

- ^ Molnar, Charles; Gair, Jane (2015-05-14). "11.4 Endocrine System".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "How the Pill Works | American Experience". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ Nussey S; Whitehead S (2001). Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publ. ISBN 978-1-85996-252-7.

- ^ Ojeda, Sergio R.; Griffin, James Bennett (2000). Textbook of endocrine physiology (4th ed.). Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513541-1.

- ^ Carvalho, Denise P.; Dupuy, Corinne (2017-12-15). "Thyroid hormone biosynthesis and release". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. A century of thyroid hormone research - Vol. I: The expanded thyroid hormone network: novel metabolites and modes of action. 458: 6–15. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.038. ISSN 0303-7207. PMID 28153798. S2CID 31150531.

- ^ "What Is an Endocrinologist?". American Association of Clinical Endocrinology. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Grumbach, Melvin M.; Biller, Beverly M. K.; Braunstein, Glenn D.; Campbell, Karen K.; Carney, J. Aidan; Godley, Paul A.; Harris, Emily L.; Lee, Joseph K. T.; Oertel, Yolanda C.; Posner, Mitchell C.; Schlechte, Janet A.; Wieand, H. Samuel (2003-03-04). "Management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass ("incidentaloma")". Annals of Internal Medicine. 138 (5): 424–429. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00013. ISSN 1539-3704. PMID 12614096. S2CID 23454526.

- ^ CDC (2024-07-19). "Diabetes Basics". Diabetes. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ "North American Menopause Society (NAMS) - Focused on Providing Physicians, Practitioners & Women Menopause Information, Help & Treatment Insights". www.menopause.org. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ "Homepage". American Thyroid Association. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ "Home - Endocrine Society". www.endo-society.org.

- ^ "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists".

- ^ "American Diabetes Association". American Diabetes Association.

- ^ "Pediatric Endocrine Society". www.lwpes.org.

- ^ "American Thyroid Association - ATA". www.thyroid.org.

- ^ "Society for Endocrinology - A world-leading authority on hormones". www.endocrinology.org.

- ^ "BSPED - Home". www.bsped.org.uk.

- ^ "ESPE - European Society of Paediatric Endocrinology - Improving the clinical care of children and adolescents with endocrine conditions". www.eurospe.org.

- ^ a b c d Temple, Robert (2007) [1986]. The genius of China: 3,000 years of science, discovery & invention (3rd ed.). London: Andre Deutsch. pp. 141–145. ISBN 978-0-233-00202-6.

- ^ Freeman ER; Bloom DA; McGuire EJ (2001). "A brief history of testosterone". Journal of Urology. 165 (2): 371–3. doi:10.1097/00005392-200102000-00004. PMID 11176375.

- ^ Berthold AA (1849). "Transplantation der Hoden". Arch. Anat. Physiol. Wiss. Med. 16: 42–6.

- ^ David K; Dingemanse E; Freud J; et al. (1935). "Uber krystallinisches mannliches Hormon aus Hoden (Testosteron) wirksamer als aus harn oder aus Cholesterin bereitetes Androsteron". Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem. 233 (5–6): 281–283. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1935.233.5-6.281.

- ^ Robert James Graves at Whonamedit?

- ^ Giuseppe Flajani at Whonamedit?

- ^ Hull G (1998). "Caleb Hillier Parry 1755–1822: a notable provincial physician". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 91 (6): 335–8. doi:10.1177/014107689809100618. PMC 1296785. PMID 9771526.

- ^ Ten S; New M; Maclaren N (2001). "Clinical review 130: Addison's disease 2001". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 86 (7): 2909–22. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.7.7636. PMID 11443143.

- ^ Bayliss, W. M.; Starling, E. H. (1902-09-12). "The mechanism of pancreatic secretion". The Journal of Physiology. 28 (5). Wiley: 325–353. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1902.sp000920. ISSN 0022-3751. PMC 1540572. PMID 16992627.

- ^ Bliss M (1989). "J. J. R. Macleod and the discovery of insulin". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology. 74 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1989.sp003266. PMID 2657840.

- ^ Loewi, O. Uebertragbarkeit der Herznervenwirkung. Pfluger's Arch. ges Physiol. 1921;189:239-42.

- ^ Sutherland EW (1972). "Studies on the mechanism of hormone action". Science. 177 (4047): 401–8. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..401S. doi:10.1126/science.177.4047.401. PMID 4339614.

Endocrinology

View on GrokipediaEndocrine System Fundamentals

Major Endocrine Glands

The endocrine system comprises several major glands and organs that produce and secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream to regulate various physiological processes, including growth, metabolism, reproduction, and stress response. These glands are distributed throughout the body and often work in interconnected networks to maintain homeostasis. Key components include the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, thyroid gland, parathyroid glands, adrenal glands, pancreas, gonads, and pineal gland, each with distinct anatomical locations and secretory functions.[4] The hypothalamus, located in the lower central region of the brain within the diencephalon, serves as a critical link between the nervous and endocrine systems. It synthesizes releasing and inhibiting hormones, such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which are transported via the hypothalamic-hypophyseal portal system to regulate the pituitary gland. Structurally, the hypothalamus consists of neuronal clusters that produce these regulatory factors, enabling it to coordinate responses to environmental and internal stimuli like temperature, appetite, and blood pressure.[5][6] Closely associated with the hypothalamus is the pituitary gland, a small, pea-sized structure situated at the base of the brain in the sella turcica of the sphenoid bone, connected by the pituitary stalk. This gland is divided into the anterior pituitary, which secretes hormones like adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), growth hormone (GH), and prolactin to stimulate target glands and tissues, and the posterior pituitary, which stores and releases antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and oxytocin synthesized in the hypothalamus. The hypothalamic-pituitary axis represents a central interconnection, where hypothalamic hormones control pituitary secretions, which in turn regulate peripheral endocrine glands such as the thyroid and adrenals, forming a hierarchical coordination system for overall endocrine function.[4][6][5] The thyroid gland, a butterfly-shaped organ located in the anterior neck below the larynx and in front of the trachea, consists of two lobes connected by an isthmus and is composed of thyroid follicles lined with follicular cells that produce thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). These hormones primarily regulate basal metabolic rate, energy production, and growth by influencing cellular oxygen consumption and protein synthesis. Embedded within the thyroid are parafollicular C cells, which secrete calcitonin to help maintain calcium homeostasis.[4][6][5] Positioned on the posterior surface of the thyroid are the four parathyroid glands, small pea-sized structures typically embedded in the thyroid's connective tissue capsule. These glands secrete parathyroid hormone (PTH), which acts to elevate blood calcium levels by stimulating bone resorption, enhancing renal calcium reabsorption, and promoting vitamin D activation. Their structure features chief cells as the primary secretory units, with oxyphil cells of uncertain function.[4][6][5] The adrenal glands, also known as suprarenal glands, are paired pyramid-shaped organs perched atop each kidney in the retroperitoneal space. Each gland has an outer adrenal cortex, divided into zones that produce glucocorticoids like cortisol to manage stress responses and metabolism, mineralocorticoids such as aldosterone for electrolyte and fluid balance, and small amounts of androgens; the inner adrenal medulla, derived from neural crest tissue, secretes catecholamines including epinephrine and norepinephrine to mediate acute stress reactions. This zonal structure allows the adrenals to respond to both long-term regulatory signals from the pituitary and rapid neural inputs.[4][6][5] The pancreas, an elongated organ situated in the abdomen behind the stomach and between the duodenum and spleen, functions both exocrine and endocrine. Its endocrine component, the islets of Langerhans, comprises clusters of cells dispersed throughout the organ, including alpha cells that secrete glucagon to raise blood glucose levels and beta cells that produce insulin to lower it, thereby maintaining glucose homeostasis essential for energy metabolism. Other islet cell types, such as delta cells secreting somatostatin, contribute to fine-tuning these processes.[4][6][5] The gonads, serving as both reproductive and endocrine organs, include the ovaries in females, located in the pelvic cavity on either side of the uterus, and the testes in males, housed in the scrotum. Ovaries secrete estrogen and progesterone to regulate reproductive cycles, secondary sexual characteristics, and pregnancy maintenance, while testes produce testosterone to support spermatogenesis, muscle development, and male secondary sex traits. These glands' functions are modulated by pituitary gonadotropins via the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, illustrating another key interconnection.[4][6][5] Finally, the pineal gland, a small pinecone-shaped structure embedded in the epithalamus at the center of the brain near the third ventricle, primarily secretes melatonin to modulate circadian rhythms and sleep-wake cycles in response to light-dark cues. Composed mainly of pinealocytes and supporting glia, it receives neural input from the retina via the suprachiasmatic nucleus, linking it indirectly to the broader neuroendocrine network.[5]Hormone Regulation Mechanisms

Hormone regulation in the endocrine system relies on intricate control mechanisms that ensure precise hormone levels to maintain homeostasis. These mechanisms integrate feedback loops, rhythmic secretion patterns, neural inputs, and hierarchical signaling to respond dynamically to physiological needs. Central to this is the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, where the hypothalamus orchestrates responses through releasing and inhibiting factors that modulate pituitary hormone secretion, ultimately influencing peripheral glands.[4] Negative feedback loops predominate in endocrine regulation, where elevated hormone levels inhibit upstream signals to prevent overproduction. For instance, in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cortisol from the adrenal cortex binds to glucocorticoid receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary, suppressing the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), respectively. This loop maintains cortisol within physiological ranges, with mineralocorticoid receptors providing additional fine-tuning for homeostasis. Positive feedback, though rarer, amplifies signals temporarily; in the HPA system, it can stabilize responses during acute stress by enhancing initial CRH-ACTH surges before negative feedback dominates.[7][8] Many hormones exhibit pulsatile secretion, characterized by episodic bursts superimposed on a baseline, which is essential for effective receptor activation and preventing desensitization. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from hypothalamic neurons pulses every 45-180 minutes, driving corresponding luteinizing hormone (LH) pulses from the pituitary to support reproductive function; disruptions in this rhythm can lead to hypogonadotropism. Similarly, ACTH secretion occurs in ultradian pulses modulated by CRH, contributing to cortisol's daily profile. These patterns arise from synchronized neuronal firing and calcium-dependent exocytosis in secretory cells.[9][10] Circadian rhythms further impose 24-hour oscillations on hormone secretion, synchronized by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus to align with environmental cues like light-dark cycles. Melatonin, secreted by the pineal gland, peaks nocturnally (around 02:00-04:00) under darkness, driven by norepinephrine activation of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase; light exposure rapidly suppresses this via SCN-mediated inhibition. This rhythm integrates photoperiod information to regulate sleep and seasonal breeding, with plasma levels reaching 60-70 pg/mL at night. Cortisol also follows a circadian pattern, with morning acrophase tied to ACTH pulses, underscoring the interplay between ultradian and circadian controls.[11][9] Neural regulation modulates endocrine activity through the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and direct hypothalamic inputs, enabling rapid adjustments to stressors or metabolic changes. The hypothalamus, particularly the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), integrates sensory signals and projects to brainstem autonomic centers, activating sympathetic pathways to stimulate adrenal medulla catecholamine release or parasympathetic inputs for glandular inhibition. For example, sympathetic innervation enhances pancreatic insulin secretion during hypoglycemia, while hypothalamic CRH neurons in the PVN coordinate HPA activation alongside ANS responses like increased heart rate. This neural overlay allows the endocrine system to respond within seconds, complementing slower hormonal feedback.[12][13] Hormonal hierarchies establish a tiered control structure, with primary signals from the hypothalamus directing secondary pituitary tropic hormones that govern tertiary peripheral outputs. Hypothalamic releasing hormones, such as CRH, GnRH, and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), are secreted into the hypophyseal portal system to stimulate anterior pituitary cells, exemplifying primary control. Pituitary tropic hormones like ACTH, LH/FSH, and TSH then act on target glands (adrenals, gonads, thyroid) as secondary regulators, with negative feedback from end hormones closing the loop. This cascade, rooted in the hypothalamus as the apex, ensures coordinated multi-level regulation across the endocrine axes.[14][4]Hormone Classification and Function

Chemical Classes of Hormones

Hormones are classified into three primary chemical classes based on their molecular structure and biosynthetic pathways: amine-derived hormones, peptide and protein hormones, and steroid hormones. This categorization reflects differences in their synthesis, physicochemical properties, and physiological handling, which are critical for understanding endocrine function.[15] Amine-derived hormones originate from amino acids, specifically tyrosine or tryptophan, and include several subclasses with distinct properties. Catecholamines, such as epinephrine and norepinephrine, are synthesized from tyrosine via sequential enzymatic hydroxylation and decarboxylation in the adrenal medulla and sympathetic neurons. These hormones are water-soluble and exhibit very short half-lives, typically around 1-2 minutes, allowing rapid signaling.[16][17] Thyroid hormones, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), are also derived from tyrosine but undergo iodination within the thyroid gland, resulting in lipid-soluble molecules with longer half-lives—T4 approximately 7 days and T3 about 1 day.[18][19] Additionally, melatonin, derived from tryptophan in the pineal gland, is a lipid-soluble amine hormone involved in regulating sleep-wake cycles, with a half-life of about 45 minutes and circulating primarily bound to albumin.[15] Peptide and protein hormones consist of chains of amino acids produced through gene transcription, ribosomal translation on the rough endoplasmic reticulum, and subsequent post-translational modifications such as cleavage and glycosylation in the Golgi apparatus. These hormones are water-soluble and generally have half-lives ranging from minutes to hours, enabling precise regulation of physiological processes. Representative examples include insulin, a 51-amino-acid peptide hormone secreted by pancreatic beta cells, and growth hormone, a 191-amino-acid protein produced by the anterior pituitary.[15][20][21][22] Steroid hormones are synthesized from cholesterol as the precursor lipid, involving cytochrome P450 enzyme-mediated conversions primarily in the mitochondria and smooth endoplasmic reticulum of endocrine cells. Due to their lipophilic nature, these hormones readily diffuse across cell membranes and possess half-lives typically in the range of 30 minutes to several hours. Key examples are cortisol, produced by the adrenal cortex, and estrogen (estradiol), synthesized in the ovaries.[15][23][17] The chemical classes differ markedly in solubility, transport mechanisms, and persistence in circulation, as summarized below:| Chemical Class | Solubility | Transport in Blood | Typical Half-Life | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amine-derived | Water-soluble (catecholamines); Lipid-soluble (thyroid hormones, melatonin) | Mostly unbound (catecholamines); Bound to thyroxine-binding globulin (thyroid hormones); Bound to albumin (melatonin) | Seconds to minutes (catecholamines); Days (thyroid hormones); ~45 minutes (melatonin) | Epinephrine, thyroxine, melatonin |

| Peptide/Protein | Water-soluble | Mostly unbound; some bound to carriers | Minutes to hours | Insulin, growth hormone |

| Steroid | Lipid-soluble | >90% bound to plasma proteins (e.g., corticosteroid-binding globulin, sex hormone-binding globulin) | Minutes to hours | Cortisol, estrogen |