Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Antiestrogen

View on Wikipedia| Antiestrogen | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Estrogen antagonists; Estrogen blockers; Estradiol antagonists |

| Use | Breast cancer; Infertility; Male hypogonadism; Gynecomastia; transgender men |

| ATC code | L02BA |

| Biological target | Estrogen receptor |

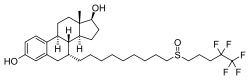

| Chemical class | Steroidal; Nonsteroidal (triphenylethylene, others) |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D020847 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Antiestrogens, also known as estrogen antagonists or estrogen blockers, are a class of drugs which prevent estrogens like estradiol from mediating their biological effects in the body. They act by blocking the estrogen receptor (ER) and/or inhibiting or suppressing estrogen production.[1][2] Antiestrogens are one of three types of sex hormone antagonists, the others being antiandrogens and antiprogestogens.[3] Antiestrogens are commonly used to stop steroid hormones, estrogen, from binding to the estrogen receptors leading to the decrease of estrogen levels.[4] Decreased levels of estrogen can lead to complications in sexual development.[5]

Types and examples

[edit]Antiestrogens include selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen, clomifene, and raloxifene, the ER silent antagonist and selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) fulvestrant,[6][7] aromatase inhibitors (AIs) like anastrozole, and antigonadotropins including androgens/anabolic steroids, progestogens, and GnRH analogues.

Estrogen receptors (ER) like ERα and ERβ include activation function 1 (AF1) domain and activation function 2 (AF2) domain in which SERMS act as antagonists for the AF2 domain, while "pure" antiestrogens like ICI 182,780 and ICI 164,384 are antagonists for the AF1 and AF2 domains.[8]

Although aromatase inhibitors and antigonadotropins can be considered antiestrogens by some definitions, they are often treated as distinct classes.[9] Aromatase inhibitors and antigonadotropins reduce the production of estrogen, while the term "antiestrogen" is often reserved for agents reducing the response to estrogen.[10]

Medical uses

[edit]Antiestrogens are used for:

- Estrogen deprivation therapy in the treatment of ER-positive breast cancer

- Ovulation induction in infertility due to anovulation

- Male hypogonadism

- Gynecomastia (breast development in men)

- A component of hormone replacement therapy for transgender men

Side effects

[edit]In women, the side effects of antiestrogens include hot flashes, osteoporosis, breast atrophy, vaginal dryness, and vaginal atrophy. In addition, they may cause depression and reduced libido.

Pharmacology

[edit]Antiestrogens act as antagonists of the estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ.

| Ligand | Other names | Relative binding affinities (RBA, %)a | Absolute binding affinities (Ki, nM)a | Action | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | ERβ | ERα | ERβ | |||

| Estradiol | E2; 17β-Estradiol | 100 | 100 | 0.115 (0.04–0.24) | 0.15 (0.10–2.08) | Estrogen |

| Estrone | E1; 17-Ketoestradiol | 16.39 (0.7–60) | 6.5 (1.36–52) | 0.445 (0.3–1.01) | 1.75 (0.35–9.24) | Estrogen |

| Estriol | E3; 16α-OH-17β-E2 | 12.65 (4.03–56) | 26 (14.0–44.6) | 0.45 (0.35–1.4) | 0.7 (0.63–0.7) | Estrogen |

| Estetrol | E4; 15α,16α-Di-OH-17β-E2 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.9 | 19 | Estrogen |

| Alfatradiol | 17α-Estradiol | 20.5 (7–80.1) | 8.195 (2–42) | 0.2–0.52 | 0.43–1.2 | Metabolite |

| 16-Epiestriol | 16β-Hydroxy-17β-estradiol | 7.795 (4.94–63) | 50 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 17-Epiestriol | 16α-Hydroxy-17α-estradiol | 55.45 (29–103) | 79–80 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 16,17-Epiestriol | 16β-Hydroxy-17α-estradiol | 1.0 | 13 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestradiol | 2-OH-E2 | 22 (7–81) | 11–35 | 2.5 | 1.3 | Metabolite |

| 2-Methoxyestradiol | 2-MeO-E2 | 0.0027–2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Hydroxyestradiol | 4-OH-E2 | 13 (8–70) | 7–56 | 1.0 | 1.9 | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestradiol | 4-MeO-E2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestrone | 2-OH-E1 | 2.0–4.0 | 0.2–0.4 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Methoxyestrone | 2-MeO-E1 | <0.001–<1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Hydroxyestrone | 4-OH-E1 | 1.0–2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestrone | 4-MeO-E1 | <1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 16α-Hydroxyestrone | 16α-OH-E1; 17-Ketoestriol | 2.0–6.5 | 35 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestriol | 2-OH-E3 | 2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestriol | 4-MeO-E3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol sulfate | E2S; Estradiol 3-sulfate | <1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol disulfate | Estradiol 3,17β-disulfate | 0.0004 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 3-glucuronide | E2-3G | 0.0079 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 17β-glucuronide | E2-17G | 0.0015 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 3-gluc. 17β-sulfate | E2-3G-17S | 0.0001 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estrone sulfate | E1S; Estrone 3-sulfate | <1 | <1 | >10 | >10 | Metabolite |

| Estradiol benzoate | EB; Estradiol 3-benzoate | 10 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Estradiol 17β-benzoate | E2-17B | 11.3 | 32.6 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Estrone methyl ether | Estrone 3-methyl ether | 0.145 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| ent-Estradiol | 1-Estradiol | 1.31–12.34 | 9.44–80.07 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Equilin | 7-Dehydroestrone | 13 (4.0–28.9) | 13.0–49 | 0.79 | 0.36 | Estrogen |

| Equilenin | 6,8-Didehydroestrone | 2.0–15 | 7.0–20 | 0.64 | 0.62 | Estrogen |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin | 7-Dehydro-17β-estradiol | 7.9–113 | 7.9–108 | 0.09 | 0.17 | Estrogen |

| 17α-Dihydroequilin | 7-Dehydro-17α-estradiol | 18.6 (18–41) | 14–32 | 0.24 | 0.57 | Estrogen |

| 17β-Dihydroequilenin | 6,8-Didehydro-17β-estradiol | 35–68 | 90–100 | 0.15 | 0.20 | Estrogen |

| 17α-Dihydroequilenin | 6,8-Didehydro-17α-estradiol | 20 | 49 | 0.50 | 0.37 | Estrogen |

| Δ8-Estradiol | 8,9-Dehydro-17β-estradiol | 68 | 72 | 0.15 | 0.25 | Estrogen |

| Δ8-Estrone | 8,9-Dehydroestrone | 19 | 32 | 0.52 | 0.57 | Estrogen |

| Ethinylestradiol | EE; 17α-Ethynyl-17β-E2 | 120.9 (68.8–480) | 44.4 (2.0–144) | 0.02–0.05 | 0.29–0.81 | Estrogen |

| Mestranol | EE 3-methyl ether | ? | 2.5 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Moxestrol | RU-2858; 11β-Methoxy-EE | 35–43 | 5–20 | 0.5 | 2.6 | Estrogen |

| Methylestradiol | 17α-Methyl-17β-estradiol | 70 | 44 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Diethylstilbestrol | DES; Stilbestrol | 129.5 (89.1–468) | 219.63 (61.2–295) | 0.04 | 0.05 | Estrogen |

| Hexestrol | Dihydrodiethylstilbestrol | 153.6 (31–302) | 60–234 | 0.06 | 0.06 | Estrogen |

| Dienestrol | Dehydrostilbestrol | 37 (20.4–223) | 56–404 | 0.05 | 0.03 | Estrogen |

| Benzestrol (B2) | – | 114 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Chlorotrianisene | TACE | 1.74 | ? | 15.30 | ? | Estrogen |

| Triphenylethylene | TPE | 0.074 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Triphenylbromoethylene | TPBE | 2.69 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Tamoxifen | ICI-46,474 | 3 (0.1–47) | 3.33 (0.28–6) | 3.4–9.69 | 2.5 | SERM |

| Afimoxifene | 4-Hydroxytamoxifen; 4-OHT | 100.1 (1.7–257) | 10 (0.98–339) | 2.3 (0.1–3.61) | 0.04–4.8 | SERM |

| Toremifene | 4-Chlorotamoxifen; 4-CT | ? | ? | 7.14–20.3 | 15.4 | SERM |

| Clomifene | MRL-41 | 25 (19.2–37.2) | 12 | 0.9 | 1.2 | SERM |

| Cyclofenil | F-6066; Sexovid | 151–152 | 243 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Nafoxidine | U-11,000A | 30.9–44 | 16 | 0.3 | 0.8 | SERM |

| Raloxifene | – | 41.2 (7.8–69) | 5.34 (0.54–16) | 0.188–0.52 | 20.2 | SERM |

| Arzoxifene | LY-353,381 | ? | ? | 0.179 | ? | SERM |

| Lasofoxifene | CP-336,156 | 10.2–166 | 19.0 | 0.229 | ? | SERM |

| Ormeloxifene | Centchroman | ? | ? | 0.313 | ? | SERM |

| Levormeloxifene | 6720-CDRI; NNC-460,020 | 1.55 | 1.88 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Ospemifene | Deaminohydroxytoremifene | 0.82–2.63 | 0.59–1.22 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Bazedoxifene | – | ? | ? | 0.053 | ? | SERM |

| Etacstil | GW-5638 | 4.30 | 11.5 | ? | ? | SERM |

| ICI-164,384 | – | 63.5 (3.70–97.7) | 166 | 0.2 | 0.08 | Antiestrogen |

| Fulvestrant | ICI-182,780 | 43.5 (9.4–325) | 21.65 (2.05–40.5) | 0.42 | 1.3 | Antiestrogen |

| Propylpyrazoletriol | PPT | 49 (10.0–89.1) | 0.12 | 0.40 | 92.8 | ERα agonist |

| 16α-LE2 | 16α-Lactone-17β-estradiol | 14.6–57 | 0.089 | 0.27 | 131 | ERα agonist |

| 16α-Iodo-E2 | 16α-Iodo-17β-estradiol | 30.2 | 2.30 | ? | ? | ERα agonist |

| Methylpiperidinopyrazole | MPP | 11 | 0.05 | ? | ? | ERα antagonist |

| Diarylpropionitrile | DPN | 0.12–0.25 | 6.6–18 | 32.4 | 1.7 | ERβ agonist |

| 8β-VE2 | 8β-Vinyl-17β-estradiol | 0.35 | 22.0–83 | 12.9 | 0.50 | ERβ agonist |

| Prinaberel | ERB-041; WAY-202,041 | 0.27 | 67–72 | ? | ? | ERβ agonist |

| ERB-196 | WAY-202,196 | ? | 180 | ? | ? | ERβ agonist |

| Erteberel | SERBA-1; LY-500,307 | ? | ? | 2.68 | 0.19 | ERβ agonist |

| SERBA-2 | – | ? | ? | 14.5 | 1.54 | ERβ agonist |

| Coumestrol | – | 9.225 (0.0117–94) | 64.125 (0.41–185) | 0.14–80.0 | 0.07–27.0 | Xenoestrogen |

| Genistein | – | 0.445 (0.0012–16) | 33.42 (0.86–87) | 2.6–126 | 0.3–12.8 | Xenoestrogen |

| Equol | – | 0.2–0.287 | 0.85 (0.10–2.85) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Daidzein | – | 0.07 (0.0018–9.3) | 0.7865 (0.04–17.1) | 2.0 | 85.3 | Xenoestrogen |

| Biochanin A | – | 0.04 (0.022–0.15) | 0.6225 (0.010–1.2) | 174 | 8.9 | Xenoestrogen |

| Kaempferol | – | 0.07 (0.029–0.10) | 2.2 (0.002–3.00) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Naringenin | – | 0.0054 (<0.001–0.01) | 0.15 (0.11–0.33) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| 8-Prenylnaringenin | 8-PN | 4.4 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Quercetin | – | <0.001–0.01 | 0.002–0.040 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Ipriflavone | – | <0.01 | <0.01 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Miroestrol | – | 0.39 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Deoxymiroestrol | – | 2.0 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| β-Sitosterol | – | <0.001–0.0875 | <0.001–0.016 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Resveratrol | – | <0.001–0.0032 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| α-Zearalenol | – | 48 (13–52.5) | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| β-Zearalenol | – | 0.6 (0.032–13) | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Zeranol | α-Zearalanol | 48–111 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Taleranol | β-Zearalanol | 16 (13–17.8) | 14 | 0.8 | 0.9 | Xenoestrogen |

| Zearalenone | ZEN | 7.68 (2.04–28) | 9.45 (2.43–31.5) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Zearalanone | ZAN | 0.51 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Bisphenol A | BPA | 0.0315 (0.008–1.0) | 0.135 (0.002–4.23) | 195 | 35 | Xenoestrogen |

| Endosulfan | EDS | <0.001–<0.01 | <0.01 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Kepone | Chlordecone | 0.0069–0.2 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| o,p'-DDT | – | 0.0073–0.4 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| p,p'-DDT | – | 0.03 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Methoxychlor | p,p'-Dimethoxy-DDT | 0.01 (<0.001–0.02) | 0.01–0.13 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| HPTE | Hydroxychlor; p,p'-OH-DDT | 1.2–1.7 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Testosterone | T; 4-Androstenolone | <0.0001–<0.01 | <0.002–0.040 | >5000 | >5000 | Androgen |

| Dihydrotestosterone | DHT; 5α-Androstanolone | 0.01 (<0.001–0.05) | 0.0059–0.17 | 221–>5000 | 73–1688 | Androgen |

| Nandrolone | 19-Nortestosterone; 19-NT | 0.01 | 0.23 | 765 | 53 | Androgen |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone | DHEA; Prasterone | 0.038 (<0.001–0.04) | 0.019–0.07 | 245–1053 | 163–515 | Androgen |

| 5-Androstenediol | A5; Androstenediol | 6 | 17 | 3.6 | 0.9 | Androgen |

| 4-Androstenediol | – | 0.5 | 0.6 | 23 | 19 | Androgen |

| 4-Androstenedione | A4; Androstenedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| 3α-Androstanediol | 3α-Adiol | 0.07 | 0.3 | 260 | 48 | Androgen |

| 3β-Androstanediol | 3β-Adiol | 3 | 7 | 6 | 2 | Androgen |

| Androstanedione | 5α-Androstanedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| Etiocholanedione | 5β-Androstanedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| Methyltestosterone | 17α-Methyltestosterone | <0.0001 | ? | ? | ? | Androgen |

| Ethinyl-3α-androstanediol | 17α-Ethynyl-3α-adiol | 4.0 | <0.07 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Ethinyl-3β-androstanediol | 17α-Ethynyl-3β-adiol | 50 | 5.6 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Progesterone | P4; 4-Pregnenedione | <0.001–0.6 | <0.001–0.010 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Norethisterone | NET; 17α-Ethynyl-19-NT | 0.085 (0.0015–<0.1) | 0.1 (0.01–0.3) | 152 | 1084 | Progestogen |

| Norethynodrel | 5(10)-Norethisterone | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | <0.1–0.22 | 14 | 53 | Progestogen |

| Tibolone | 7α-Methylnorethynodrel | 0.5 (0.45–2.0) | 0.2–0.076 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Δ4-Tibolone | 7α-Methylnorethisterone | 0.069–<0.1 | 0.027–<0.1 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| 3α-Hydroxytibolone | – | 2.5 (1.06–5.0) | 0.6–0.8 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| 3β-Hydroxytibolone | – | 1.6 (0.75–1.9) | 0.070–0.1 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Footnotes: a = (1) Binding affinity values are of the format "median (range)" (# (#–#)), "range" (#–#), or "value" (#) depending on the values available. The full sets of values within the ranges can be found in the Wiki code. (2) Binding affinities were determined via displacement studies in a variety of in-vitro systems with labeled estradiol and human ERα and ERβ proteins (except the ERβ values from Kuiper et al. (1997), which are rat ERβ). Sources: See template page. | ||||||

History

[edit]The first nonsteroidal antiestrogen was discovered by Lerner and coworkers in 1958.[11] Ethamoxytriphetol (MER-25) was the first antagonist of the ER to be discovered,[12] followed by clomifene and tamoxifen.[13][14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of antiestrogen - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms, Definition of antiestrogen - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms".,

- ^ "antiestrogen" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Nath JL (2006). Using Medical Terminology: A Practical Approach. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 977–. ISBN 978-0-7817-4868-1.

- ^ McKeage K, Curran MP, Plosker GL (2004-03-01). "Fulvestrant: a review of its use in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women with disease progression following antiestrogen therapy". Drugs. 64 (6): 633–48. doi:10.2165/00003495-200464060-00009. PMID 15018596. S2CID 242916244.

- ^ Amenyogbe E, Chen G, Wang Z, Lu X, Lin M, Lin AY (2020-02-07). "A Review on Sex Steroid Hormone Estrogen Receptors in Mammals and Fish". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2020 5386193. doi:10.1155/2020/5386193. PMC 7029290. PMID 32089683.

- ^ Ottow E, Weinmann H (8 September 2008). Nuclear Receptors as Drug Targets. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-3-527-62330-3.

- ^ Chabner BA, Longo DL (8 November 2010). Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 660–. ISBN 978-1-60547-431-1.

- ^ Pike, Ashley C.W.; Brzozowski, A.Marek; Walton, Julia; Hubbard, Roderick E.; Thorsell, Ann-Gerd; Li, Yi-Lin; Gustafsson, Jan-Åke; Carlquist, Mats (2001-02-01). "Structural Insights into the Mode of Action of a Pure Antiestrogen". Structure. 9 (2): 145–153. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00568-8. ISSN 0969-2126. PMID 11250199.

- ^ Riggins RB, Bouton AH, Liu MC, Clarke R (2005). Antiestrogens, aromatase inhibitors, and apoptosis in breast cancer. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 71. pp. 201–37. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(05)71007-4. ISBN 978-0-12-709871-5. PMID 16112269.

- ^ Thiantanawat A, Long BJ, Brodie AM (November 2003). "Signaling pathways of apoptosis activated by aromatase inhibitors and antiestrogens". Cancer Research. 63 (22): 8037–50. PMID 14633737.

- ^ MacGregor JI, Jordan VC (June 1998). "Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action". Pharmacological Reviews. 50 (2): 151–96. PMID 9647865.

- ^ Maximov PY, McDaniel RE, Jordan VC (23 July 2013). Tamoxifen: Pioneering Medicine in Breast Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-3-0348-0664-0.

- ^ Jordan VC (27 May 2013). Estrogen Action, Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators and Women's Health: Progress and Promise. World Scientific. pp. 7, 112. ISBN 978-1-84816-959-3.

- ^ Sneader W (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

External links

[edit] Media related to Antiestrogens at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antiestrogens at Wikimedia Commons

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Dictionary of Cancer Terms. U.S. National Cancer Institute.

This article incorporates public domain material from Dictionary of Cancer Terms. U.S. National Cancer Institute.

Antiestrogen

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Core Definition

Antiestrogens are pharmacological agents that counteract the physiological effects of estrogen hormones by binding to estrogen receptors (ERs) and inhibiting ER-mediated gene transcription.[1] These compounds competitively antagonize endogenous estrogens at ERα and ERβ subtypes, preventing receptor dimerization, DNA binding, and recruitment of coactivators necessary for transcriptional activation.[9] As of 2023, antiestrogens remain foundational in endocrine therapies, with clinical use documented since the 1970s for conditions driven by estrogen-dependent cellular proliferation.[10] The class includes selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), which elicit tissue-specific responses by inducing distinct ER conformations that favor corepressor recruitment in certain contexts (e.g., antagonism in mammary tissue) while permitting agonism elsewhere (e.g., bone preservation). Examples like tamoxifen, approved by the FDA in 1977, exemplify SERMs' mixed pharmacology, reducing breast cancer recurrence by 47% in adjuvant settings per meta-analyses of randomized trials involving over 100,000 patients.[11] Pure antiestrogens, or selective ER degraders (SERDs), differ by fully antagonizing ER without agonistic activity and promoting ubiquitin-mediated receptor proteasomal degradation, as seen with fulvestrant (FDA-approved 2002), which achieves near-complete ER downregulation in preclinical models.[12] [13] Beyond direct ER interactions, some antiestrogens influence non-genomic signaling pathways, such as MAPK or PI3K/Akt cascades, independent of receptor status, contributing to antiproliferative effects in estrogen-independent cells.[3] Empirical evidence from structure-activity studies confirms that antiestrogenic potency correlates with side-chain modifications enhancing ER affinity and impairing coactivator binding, with dissociation constants (Kd) for high-affinity ligands typically below 1 nM.[14] This mechanistic diversity underscores antiestrogens' utility in targeting estrogen-driven pathologies while minimizing off-target estrogenic risks.Major Classes

The major classes of antiestrogens encompass selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and selective estrogen receptor degraders/downregulators (SERDs), which differ in their binding profiles and downstream effects on the estrogen receptor (ER).[2][15] SERMs, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, bind competitively to the ER and exhibit tissue-specific partial agonist or antagonist activity; for instance, they antagonize ER signaling in breast tissue while promoting it in bone to mitigate osteoporosis risk.[2][16] This dual functionality arises from conformational changes in the receptor-ligand complex that recruit different co-regulators, leading to variable transcriptional outcomes across cell types.[15] In contrast, SERDs like fulvestrant act as pure antagonists by binding to the ER, inducing a conformation that prevents co-activator recruitment and promotes receptor ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thereby eliminating ER-mediated signaling without agonist effects in any tissue.[2][15] Fulvestrant, a steroidal SERD, requires intramuscular administration due to poor oral bioavailability, though newer oral SERDs (e.g., elacestrant, approved in 2023 for ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer) represent an emerging subclass with similar degradative mechanisms but improved pharmacokinetics.[17][18] These classes are distinguished from estrogen synthesis inhibitors like aromatase inhibitors, which reduce circulating estrogen levels but do not directly interact with the ER.[19]Mechanisms of Action

Estrogen Receptor Interactions

Antiestrogens interact with estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), nuclear transcription factors that regulate gene expression in response to estrogens like 17β-estradiol. These compounds competitively bind to the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of the ER, with affinities comparable to or exceeding that of estradiol, thereby inhibiting estrogen-induced receptor activation. Binding affinities vary by subclass; for instance, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen exhibit high-affinity binding to ERα (Kd ≈ 0.1-1 nM), while selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) like fulvestrant show similar potency. This competitive antagonism prevents endogenous estrogen from occupying the receptor, disrupting downstream signaling pathways essential for cell proliferation in estrogen-dependent tissues.[20][21] Upon binding, antiestrogens induce unique conformational changes in the ER LBD, distinct from those elicited by agonists. Agonist binding repositions helix 12 (H12) to form a hydrophobic groove for coactivator recruitment via nuclear receptor boxes (LXXLL motifs), enabling transcriptional activation through AF-2 domain interactions. In contrast, antagonists displace or misposition H12, blocking this groove and favoring corepressor binding or transcriptional repression; crystallographic studies confirm raloxifene-bound ERβ structures where H12 protrudes into the coactivator site. These changes alter ER dimerization, DNA binding to estrogen response elements (EREs), and chromatin interactions, often resulting in recruitment of NCoR/SMRT corepressors that facilitate histone deacetylation and gene silencing.[22][23][24] SERMs and SERDs differ in their induced conformations and functional outcomes at the ER. SERMs like tamoxifen stabilize an inactive ER conformation that retains partial agonist activity in tissues expressing high AF-1 domain function, such as bone or endometrium, due to ligand-independent phosphorylation and co-regulator selectivity. SERDs, however, promote a more destabilized conformation that impairs nuclear translocation and enhances proteasomal targeting, though their primary antagonism stems from H12 disruption akin to SERMs. These interactions underpin tissue-specific effects, with SERM-bound ER showing differential coactivator/corepressor recruitment profiles between ERα and ERβ isoforms.[25][21][26]Selective Modulation and Degradation

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) bind to estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) with high affinity, inducing a unique conformational change that dictates tissue-specific agonist or antagonist activity rather than uniform blockade.[27] This selectivity stems from differential recruitment of coactivators and corepressors in various cell types; for instance, in breast tissue, SERMs like tamoxifen favor corepressor binding, suppressing ER-mediated transcription and proliferation, whereas in bone, they promote coactivator interactions that mimic estrogen's protective effects on density.[11] The partial agonist nature of SERMs arises because their ER-ligand complexes exhibit reduced transcriptional efficacy compared to estradiol-bound ER, with helix 12 of the receptor adopting a position that partially occludes coactivator binding sites.[27] In contrast, selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) not only antagonize ER function but also target the receptor for proteasomal degradation, achieving near-complete elimination of ER protein levels.[28] Prototypical SERDs such as fulvestrant bind ERα, inducing a conformation that impairs nuclear translocation, enhances ubiquitination via E3 ligases, and recruits the 26S proteasome for degradation, thereby disrupting estrogen signaling more potently than competitive antagonists alone.[29] This degradation mechanism reduces ER availability for ligand binding and transcriptional activity, with studies showing up to 80-90% reduction in ERα levels in responsive cells within hours of exposure.[30] Unlike SERMs, SERDs lack intrinsic agonistic activity across tissues due to their inability to stabilize functional ER dimers.[15] Emerging oral SERDs, such as elacestrant, replicate this degradation profile while improving bioavailability over injectable fulvestrant.[31]Clinical Applications

Breast Cancer Therapy

Tamoxifen, the prototypical selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), serves as a foundational antiestrogen in ER-positive breast cancer therapy, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1977 initially for metastatic disease and subsequently for adjuvant use following surgery. In early-stage ER-positive breast cancer, adjuvant tamoxifen for 5 years reduces the 15-year recurrence risk by approximately 40% and breast cancer mortality by 30%, based on meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials involving over 20,000 women.[32] Extending therapy to 10 years yields additional reductions in recurrence (by 3-4% absolute risk) and mortality (by 2-3%) compared to 5 years, as demonstrated in the ATLAS trial with 12,894 participants, though benefits accrue primarily after year 10 due to late recurrences.[33] These outcomes hold across pre- and perimenopausal women, where tamoxifen remains the standard endocrine therapy, often combined with ovarian suppression in higher-risk cases per clinical guidelines informed by trials like SOFT and TEXT.[34] Fulvestrant, a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) and pure antiestrogen, is primarily employed in advanced or metastatic ER-positive breast cancer, particularly after progression on prior endocrine therapies. Administered intramuscularly at 500 mg monthly, it competitively binds the estrogen receptor, induces conformational changes leading to receptor ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, and thereby abrogates estrogen signaling more completely than partial agonists like tamoxifen. Phase III trials, such as the first-line comparison with tamoxifen in untreated advanced disease, showed equivalent efficacy, with objective response rates of 31.6% for fulvestrant versus 33.2% for tamoxifen and median time to progression of 6.8 versus 6.5 months in hormone receptor-positive cohorts.[35] In postmenopausal women, fulvestrant monotherapy yields clinical benefit rates of 50-60% in aromatase inhibitor-pretreated patients, with the CONFIRM trial establishing 500 mg dosing superiority over 250 mg, improving median overall survival by 4.1 months (26.4 vs. 22.3 months).[36] Combination regimens enhance fulvestrant's utility; for instance, in the phase III SWOG S0226 trial of postmenopausal metastatic patients, fulvestrant plus anastrozole extended median overall survival to 47.7 months versus 41.1 months with anastrozole alone, a 19% reduction in mortality risk, without disproportionate toxicity.[37] Similarly, pairing fulvestrant with CDK4/6 inhibitors like ribociclib in the MONALEESA-3 trial doubled progression-free survival (median 20.5 vs. 12.8 months) and improved overall survival by 7 months in endocrine-resistant disease.[38] These results underscore fulvestrant's role in second- or later-line settings, though its intramuscular route and loading-dose schedule limit patient convenience compared to oral SERMs. Empirical data from over 10,000 patients across trials confirm durable responses in ER-high tumors but highlight variable efficacy tied to ESR1 mutation status, with preclinical models showing restored sensitivity via degradation of mutant receptors. Other SERMs, such as toremifene, exhibit efficacy akin to tamoxifen in metastatic settings (response rates ~20-30%), but lack superior outcomes in head-to-head trials and are less commonly used due to similar side-effect profiles without added benefits.[39] Overall, antiestrogens underpin endocrine therapy for ER-positive disease, reducing proliferation via receptor blockade or depletion, with trial-derived hazard ratios consistently favoring intervention (e.g., 0.6-0.7 for recurrence-free survival), though absolute gains depend on tumor burden, menopausal status, and genomic factors like PIK3CA alterations.[40]Non-Oncologic Uses

Antiestrogens, particularly selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), are employed in non-oncologic contexts to address disorders of reproduction, bone metabolism, and endocrine imbalances. These applications leverage their tissue-selective agonist or antagonist effects on estrogen receptors, distinct from their primary role in malignancy. Clomiphene citrate, for instance, serves as a first-line agent for ovulation induction in women with anovulatory infertility.[41] Administered orally at doses typically ranging from 50 to 150 mg daily for 5 days starting on cycle day 3-5, it antagonizes hypothalamic estrogen receptors, elevating gonadotropin-releasing hormone and subsequently follicle-stimulating hormone levels to stimulate follicular development.[42] This approach has been standard for over 50 years, achieving ovulation rates of approximately 60-80% in responsive patients, though pregnancy rates vary by underlying etiology such as polycystic ovary syndrome.[42][43] Raloxifene hydrochloride, another SERM, is FDA-approved for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. By mimicking estrogen's effects on bone while antagonizing it in other tissues, it increases bone mineral density at the lumbar spine and hip, reducing vertebral fracture risk by about 30-50% in clinical trials.[44] In the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial, daily 60 mg dosing over three years prevented one vertebral fracture per 46 treated women compared to placebo.[45] Long-term use sustains these benefits but requires adherence to maintain density gains, with no established efficacy against non-vertebral fractures.[46] Tamoxifen, though primarily associated with oncologic indications, is utilized off-label for gynecomastia, particularly in pubertal or idiopathic cases causing pain or cosmetic distress. Doses of 10-20 mg daily for 3-6 months reduce breast tenderness and size by competitively inhibiting estrogen binding in mammary tissue.[47] Double-blind studies demonstrate resolution in up to 80% of recent-onset cases, with minimal side effects and low relapse rates upon discontinuation.[48][49] This treatment is preferred over surgery for reversible etiologies, though evidence is derived from smaller cohorts rather than large randomized trials.[50]Efficacy and Evidence

Empirical Outcomes in Treatment

In adjuvant treatment of estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) early breast cancer, tamoxifen administered for 5 years has been shown to reduce the 15-year risk of recurrence by approximately 50% and breast cancer mortality by 33% compared to no endocrine therapy, based on individual patient data from 20 randomized trials involving over 20,000 women.[51] [52] This benefit persists long-term, with a one-third reduction in breast cancer deaths observed throughout 15 years of follow-up in ER+ cases.[51] Extended therapy beyond 5 years further lowers recurrence risk but increases certain adverse events, as evidenced by trials like ATLAS, where 10 years of tamoxifen reduced breast cancer mortality by an additional 3.7% absolute risk at 15 years compared to 5 years.[53] For advanced or metastatic ER+ breast cancer, selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) like fulvestrant demonstrate superior progression-free survival (PFS) over aromatase inhibitors in endocrine-sensitive settings. In the phase III FALCON trial of 462 postmenopausal patients, fulvestrant 500 mg yielded a median PFS of 16.6 months versus 13.8 months with anastrozole (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79, p=0.049), with overall survival (OS) benefits emerging in long-term follow-up (HR 0.85).[54] The CONFIRM trial confirmed dose-dependent efficacy, with fulvestrant 500 mg achieving a clinical benefit rate of 50.6% versus 39.6% for 250 mg in tamoxifen-pretreated advanced disease (median PFS 6.5 vs. 5.5 months, p=0.006).[36] Combinations enhance outcomes; for instance, fulvestrant plus anastrozole in the phase III SWOG S0226 trial prolonged median OS to 49.6 months versus 41.7 months with anastrozole alone in metastatic ER+/HER2- disease (HR 0.80, p=0.04).[37] In second-line settings post-aromatase inhibitor failure, fulvestrant plus AKT inhibitor capivasertib improved median PFS to 7.2 months versus 3.6 months with placebo plus fulvestrant in the phase III CAPItello-291 trial (HR 0.50, p<0.001), particularly in patients with PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN alterations.[55] Raloxifene, another SERM, shows comparable but slightly inferior efficacy to tamoxifen in adjuvant settings, with meta-analyses indicating risk reductions for invasive breast cancer but higher thromboembolic risks.[56] Non-oncologic applications, such as clomiphene for ovulatory infertility, yield live birth rates of 20-25% per cycle in randomized trials, though evidence is dated and confounded by variable dosing and patient selection.[57] Empirical data for other uses like gynecomastia reduction remain limited to small observational studies, with response rates around 80% but lacking large-scale randomized validation.[57]Comparative Effectiveness

In postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer, aromatase inhibitors (AIs) such as letrozole, anastrozole, and exemestane demonstrate superior efficacy compared to selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen in adjuvant settings, reducing recurrence rates by approximately 30% during treatment periods based on meta-analyses of randomized trials involving over 30,000 patients. [58] This benefit is attributed to more profound estrogen suppression by AIs, leading to improved disease-free survival (DFS), though overall survival differences are less consistent and emerge primarily in node-positive cases.[59] In contrast, tamoxifen remains effective but shows higher rates of distant recurrence, particularly in years 2-5 of therapy.[60] For metastatic breast cancer, fulvestrant, a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD), exhibits comparable time to progression and overall response rates to tamoxifen in hormone receptor-positive cases, as evidenced by phase III trials where fulvestrant achieved similar clinical benefits without inferiority in efficacy.[61] However, fulvestrant 500 mg dosing outperforms lower doses and matches or exceeds third-generation AIs like anastrozole in progression-free survival (PFS), with hazard ratios favoring fulvestrant in second-line settings post-AI failure (e.g., median PFS of 6.5 months vs. 5.5 months for anastrozole).[62] [63] Tamoxifen, while versatile across menopausal statuses, yields inferior outcomes to AIs in postmenopausal metastatic disease, with letrozole showing higher objective response rates (e.g., 30% vs. 20%) and longer time to progression in direct comparisons.[64] In premenopausal women, tamoxifen outperforms AIs used without ovarian suppression, as AIs require estrogen ablation via gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or oophorectomy to achieve efficacy parity, per randomized data indicating no standalone benefit for AIs in this group.[58] [65] For breast cancer prevention in high-risk women, network meta-analyses rank AIs slightly above tamoxifen in risk reduction (e.g., 50-65% relative reduction for both, but AIs with marginally better invasive cancer prevention), though adherence and side-effect profiles influence net benefits.[56] These comparisons underscore that while SERMs provide broad utility, AIs and SERDs offer enhanced suppression in estrogen-driven disease, with choices guided by menopausal status and prior therapies.[66]Resistance and Challenges

Biological Mechanisms of Resistance

Endocrine resistance to antiestrogens in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer manifests through ER-dependent mechanisms that alter receptor function and ER-independent pathways that activate alternative proliferative signals. These adaptations allow tumor cells to evade blockade of ER signaling by selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen or selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) like fulvestrant.[67][68] ER-dependent resistance primarily involves mutations in the ESR1 gene encoding ERα, particularly in the ligand-binding domain, such as Y537S and D538G variants. These mutations stabilize a constitutively active ER conformation, promoting ligand-independent transcriptional activity and proliferation even in the presence of antiestrogens; Y537S and D538G are prevalent in metastatic disease following aromatase inhibitor exposure.[68] Additional ER-dependent changes include altered coregulator dynamics, where overexpression of coactivators like SRC-3 (AIB1) enhances ER-mediated gene expression resistant to tamoxifen, while downregulation of corepressors such as NCOR1 and NCOR2 diminishes repressive effects on ER target genes.[67] ER-independent mechanisms decouple tumor growth from ER signaling altogether. Loss of ER expression occurs in 10-20% of initially ER+ cases at relapse, rendering antiestrogen therapies ineffective by eliminating the target receptor.[68] Hyperactivation of growth factor receptor pathways, including HER2, EGFR, IGF1R, and FGFR1/3 amplification, drives crosstalk with downstream MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR cascades, phosphorylating ER at sites like S167/S118 to sustain ligand-independent activity or bypass ER entirely.[67] PIK3CA mutations or PTEN loss further amplify PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, promoting cell survival and resistance.[68] Cell cycle deregulation contributes via cyclin D1 overexpression or CDK4/6 hyperactivity, overriding antiestrogen-induced G1 arrest, while epigenetic modifications such as ESR1 promoter hypermethylation silence receptor expression and non-coding RNAs (e.g., miR-221/222, HOTAIR) modulate pathway activation.[68][67] These mechanisms often converge, with tumor microenvironment factors like hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) exacerbating compensatory signaling in advanced disease.[68]Clinical Management of Resistance

In patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer exhibiting resistance to initial antiestrogen therapy, such as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or aromatase inhibitors (AIs), management strategies emphasize combination regimens with targeted agents to restore sensitivity or exploit alternative pathways.[69] Secondary endocrine resistance, defined as relapse after at least two years on adjuvant therapy or within 12 months of discontinuation, prompts escalation to cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors combined with fulvestrant or continued AIs, which extend progression-free survival (PFS) by 6-10 months in metastatic settings based on phase III trials like PALOMA-3, MONALEESA-3, and MONARCH-2.[69][68] These combinations target cell cycle progression while maintaining estrogen receptor (ER) antagonism, with abemaciclib and ribociclib demonstrating overall survival benefits in endocrine-pretreated patients.[70] Biomarker-driven approaches refine selection: for PIK3CA-mutated tumors (prevalent in 30-40% of HR+ cases), alpelisib plus fulvestrant yields a median PFS of 11 months versus 5.7 months with placebo plus fulvestrant, per the SOLAR-1 trial.[69] Similarly, everolimus with exemestane, targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, improves PFS to 7.8 months from 3.2 months in the BOLERO-2 trial for post-endocrine therapy progression.[69] Liquid biopsies for circulating tumor DNA enable detection of ESR1 mutations, which confer ligand-independent ER activity and occur in up to 20% of metastatic HR+ cancers post-AI exposure; elacestrant, an oral selective ER degrader (SERD), shows superior PFS (3.8 months vs. 1.9 months) in ESR1-mutated subsets from the EMERALD trial, leading to FDA approval in January 2023 for pretreated ER+/HER2- advanced disease.[71][72] Therapy sequencing prioritizes non-chemotherapy options absent visceral crisis: after first-line ET plus CDK4/6 inhibition, guidelines recommend switching to fulvestrant-based combinations or elacestrant for ESR1 alterations, reserving chemotherapy (e.g., capecitabine or eribulin) for rapid progression.[68] Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials confirm that targeted therapy plus endocrine combinations reduce PFS hazard ratios to 0.68 overall, though acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors via RB1 loss or pathway reactivation necessitates ongoing biomarker monitoring and trial enrollment for novel agents like PROTACs or dual ER/proteasome degraders.[68] Patient-specific factors, including menopausal status and comorbidities, guide choices, with postmenopausal women deriving most benefit from AI-CDK4/6i switches.[69]Adverse Effects

Acute and Common Side Effects

Antiestrogens, including selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, and selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) like fulvestrant, frequently induce vasomotor symptoms due to the blockade or degradation of estrogen receptors, mimicking menopausal effects. Hot flashes and night sweats occur in up to 64% of patients on tamoxifen, often emerging acutely within weeks of initiation.[73] [5] Similar symptoms affect 10-25% of fulvestrant users, alongside nausea reported in approximately 10-20% of cases.[74] [75] For tamoxifen, additional common effects encompass vaginal discharge or dryness (affecting about 35% of users), menstrual irregularities or spotting, fatigue, and nausea, with onset typically early in treatment.[73] [76] Raloxifene shares overlapping profiles, with hot flashes, leg cramps, joint pain, and flu-like symptoms being prevalent, reported in over 10% of patients in clinical data.[44] Fulvestrant, administered intramuscularly, uniquely causes acute injection-site pain or reactions in up to 20-30% of recipients, often resolving within days but recurring with dosing.[74] [77] Gastrointestinal disturbances like nausea and vomiting, as well as musculoskeletal complaints such as arthralgia or myalgia, appear across classes, with incidence rates of 5-15% for fulvestrant and variable for SERMs.[74] [78] These effects are generally manageable with supportive care but contribute to treatment discontinuation in 5-10% of cases for tamoxifen.[73] Patient monitoring for symptom severity is recommended, as individual variability influences tolerability.[5]Long-Term Risks and Criticisms

Long-term use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen has been associated with an elevated risk of endometrial cancer, with real-world data indicating a higher incidence among treated patients compared to controls.[79] This risk arises from tamoxifen's partial agonist effects on endometrial tissue, contrasting with its antagonist action in breast tissue, and becomes more pronounced with extended therapy beyond 5 years.[80] Additionally, tamoxifen increases the incidence of thromboembolic events, such as pulmonary embolism, which contributes to its risk-benefit profile in preventive settings.[81] Aromatase inhibitors (AIs), such as anastrozole and letrozole, present distinct long-term risks primarily related to estrogen suppression, including accelerated bone mineral density loss leading to osteoporosis and fractures.[82] Population-based studies have linked AI use to higher rates of heart failure and cardiovascular mortality relative to tamoxifen, potentially due to adverse lipid profiles and vascular effects from profound estrogen deprivation.[83] Persistent joint and muscle pain, reported by many patients, can endure beyond treatment cessation, impacting mobility and quality of life.[82] Criticisms of antiestrogen therapy often center on adherence challenges driven by these adverse effects, with poor physical and social well-being correlating to early discontinuation rates of up to 20-30% within 5 years, potentially compromising recurrence-free survival.[84] In low-risk or preventive contexts, the absolute benefits may be modest while risks like secondary cancers or cardiovascular events accumulate, prompting debates over overtreatment; for instance, extending tamoxifen to 10 years reduces breast cancer recurrence but elevates endometrial risks without proportional overall survival gains in all subgroups.[80] Selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) like fulvestrant show lower endometrial risks due to pure antagonism but carry concerns for injection-related complications and potential vascular events with prolonged use, though long-term data remain limited compared to SERMs and AIs.[85][86]Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Antiestrogens exert their primary effects by binding to the estrogen receptor (ER), a ligand-activated transcription factor that mediates estrogen signaling, predominantly through ERα in breast tissue. This binding inhibits estrogen-dependent gene transcription, which drives proliferation in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) cancers. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as tamoxifen, competitively bind the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of ERα and ERβ with high affinity, inducing a conformational change that repositions helix 12 (H12). This alteration prevents recruitment of coactivators like NCOA and favors corepressor (e.g., NCOR) binding, thereby blocking ER dimerization, DNA binding via estrogen response elements (EREs), and downstream transcriptional activation in antagonistic tissues like breast.[15][87] In contrast, SERMs display tissue-selective agonism, acting as partial agonists in bone and liver by permitting partial coactivator interaction, which supports bone mineral density but increases endometrial proliferation risk.[87] Selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs), exemplified by fulvestrant, function as pure antagonists without agonistic activity across tissues. They bind the ER LBD with similar or higher affinity than SERMs, promoting an unstable receptor conformation that inhibits nuclear translocation, dimerization, and DNA interaction. Unlike SERMs, SERDs trigger ubiquitin-proteasome pathway-mediated proteasomal degradation of the ER protein, reducing ER levels by up to 75-100% in ER+ cells without altering ER mRNA expression, as evidenced in preclinical models like LTED tumors where 25 mg/kg dosing achieved 30-50% downregulation.[29][15] This degradation mechanism provides more complete ER inhibition, overcoming partial antagonism limitations of SERMs and contributing to efficacy in tamoxifen-resistant settings.[29] Both classes antagonize non-genomic ER effects, such as rapid signaling via membrane-associated ER and crosstalk with growth factor pathways (e.g., EGFR, IGF-1R), though SERDs more potently disrupt these due to ER depletion.[87] Pharmacodynamic potency varies by dose; for instance, emerging oral SERDs like elacestrant exhibit dose-dependent antagonism, shifting from mixed effects at low doses to full degradation at therapeutic levels (e.g., 400 mg daily).[88] These actions collectively suppress ER-driven proliferation, with clinical pharmacodynamics confirmed by reduced ER expression and halted estrogen-responsive gene activity in treated tumors.[29]Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism

Tamoxifen, a prototypical selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), is administered orally and exhibits nearly complete bioavailability of approximately 100% due to minimal first-pass metabolism.[89] Following absorption, peak plasma concentrations are reached within 3 to 7 hours, with extensive distribution characterized by a volume of distribution of 0.5 to 1.6 L/kg and protein binding exceeding 98%, primarily to albumin.[90] Hepatic metabolism occurs predominantly via cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP3A4/5 for N-demethylation to N-desmethyltamoxifen and CYP2D6 for hydroxylation to the active metabolites 4-hydroxytamoxifen and endoxifen, the latter contributing substantially to therapeutic efficacy.[91] The terminal elimination half-life of tamoxifen is 5 to 7 days, while that of N-desmethyltamoxifen extends to about 14 days; excretion is primarily fecal via biliary secretion, with less than 10% renal.[90] Raloxifene, another SERM, also given orally, has low bioavailability of about 2% owing to extensive intestinal and hepatic first-pass glucuronidation.[92] It is rapidly absorbed but undergoes phase II metabolism exclusively via UDP-glucuronosyltransferases to glucuronide conjugates, which are inactive and excreted into bile for enterohepatic recirculation; cytochrome P450 pathways are not involved.[93] The elimination half-life is approximately 27 to 32 hours for raloxifene, with glucuronides cleared more rapidly.[94] Fulvestrant, a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD), is delivered via monthly intramuscular depot injection to circumvent poor oral bioavailability, achieving steady-state plasma concentrations after 3 to 6 months of dosing.[95] It distributes widely with high protein binding (>99%) and is metabolized in the liver through multiple biotransformation routes analogous to endogenous steroid pathways, including cytochrome P450-mediated oxidation, sulfation, and glucuronidation to less active metabolites.[96] The apparent terminal elimination half-life is about 40 days, supporting the dosing interval, with primary excretion in feces (>90%) and negligible renal contribution (<1%).[95][97]| Drug Class/Example | Route | Bioavailability | Key Metabolism | Elimination Half-Life | Primary Excretion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERM (Tamoxifen) | Oral | ~100% | Hepatic CYP3A4/5, CYP2D6 (to endoxifen, etc.) | 5–7 days (parent); ~14 days (major metabolite) | Fecal |

| SERM (Raloxifene) | Oral | ~2% | Intestinal/hepatic glucuronidation | 27–32 hours | Biliary/fecal (glucuronides) |

| SERD (Fulvestrant) | IM injection | N/A (depot) | Hepatic oxidation, conjugation | ~40 days | Fecal |