Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nicotinamide

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌnaɪəˈsɪnəmaɪd/, /ˌnɪkəˈtɪnəmaɪd/ |

| Other names | NAM, 3-pyridinecarboxamide niacinamide (USAN US) nicotinic acid amide vitamin PP nicotinic amide vitamin B3 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | oral, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.467 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H6N2O |

| Molar mass | 122.127 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.40 g/cm3 g/cm3 [1] |

| Melting point | 129.5 °C (265.1 °F) |

| Boiling point | 334 °C (633 °F) |

| |

| |

Nicotinamide (INN, BAN UK[2]) or niacinamide (USAN US) is a form of vitamin B3 found in food and used as a dietary supplement and medication.[3][4][5] As a supplement, it is used orally (swallowed by mouth) to prevent and treat pellagra (niacin deficiency).[4] While nicotinic acid (niacin) may be used for this purpose, nicotinamide has the benefit of not causing skin flushing.[4] As a cream, it is used to treat acne, and has been observed in clinical studies to improve the appearance of aging skin by reducing hyperpigmentation and redness.[5][6] It is a water-soluble vitamin.

Side effects are minimal.[7][8] At high doses, liver problems may occur.[7] Normal amounts are safe for use during pregnancy.[9] Nicotinamide is in the vitamin B family of medications, specifically the vitamin B3 complex.[10][11] It is an amide of nicotinic acid.[7] Foods that contain nicotinamide include yeast, meat, milk, and green vegetables.[12]

Nicotinamide was discovered between 1935 and 1937.[13][14] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[15][16] Nicotinamide is available as a generic medication and over the counter.[10] Commercially, nicotinamide is made from either nicotinic acid (niacin) or nicotinonitrile.[14][17] In some countries, grains have nicotinamide added to them.[14]

Extra-terrestrial nicotinamide has been found in carbonaceous chondrite meteorites.[18]

Medical uses

[edit]Niacin deficiency

[edit]Nicotinamide is the preferred treatment for pellagra, caused by niacin deficiency.[4]

Acne

[edit]Nicotinamide cream is used as a treatment for acne.[5] It has anti-inflammatory actions, which may benefit people with inflammatory skin conditions.[19]

Nicotinamide increases the biosynthesis of ceramides in human keratinocytes in vitro and improves the epidermal permeability barrier in vivo.[20] The application of 2% topical nicotinamide for 2 and 4 weeks has been found to be effective in lowering the sebum excretion rate.[21] Nicotinamide has been shown to prevent Cutibacterium acnes-induced activation of toll-like receptor 2, which ultimately results in the down-regulation of pro-inflammatory interleukin-8 production.[22]

Skin cancer

[edit]Nicotinamide at doses of 500 to 1000 mg a day decreases the risk of skin cancers, other than melanoma, in those at high risk.[23]

Side effects

[edit]Nicotinamide has minimal side effects.[7][8] At very high doses above 3 g per day acute liver toxicity has been documented in at least one case.[7] Normal doses are safe during pregnancy.[9]

Chemistry

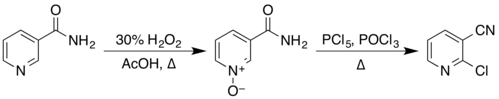

[edit]The structure of nicotinamide consists of a pyridine ring to which a primary amide group is attached in the meta position. It is an amide of nicotinic acid.[7] As an aromatic compound, it undergoes electrophilic substitution reactions and transformations of its two functional groups. Examples of these reactions reported in Organic Syntheses include the preparation of 2-chloronicotinonitrile by a two-step process via the N-oxide,[24][25]

from nicotinonitrile by reaction with phosphorus pentoxide,[26] and from 3-aminopyridine by reaction with a solution of sodium hypobromite, prepared in situ from bromine and sodium hydroxide.[27]

Industrial production

[edit]The hydrolysis of nicotinonitrile is catalysed by the enzyme nitrile hydratase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1,[28][29][17] producing 3500 tons per annum of nicotinamide for use in animal feed.[30] The enzyme allows for a more selective synthesis as further hydrolysis of the amide to nicotinic acid is avoided.[31][32] Nicotinamide can also be made from nicotinic acid. According to Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, worldwide 31,000 tons of nicotinamide were sold in 2014.[14]

Biochemistry

[edit]

Nicotinamide, as a part of the cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH / NAD+) is crucial to life. In cells, nicotinamide is incorporated into NAD+ and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+). NAD+ and NADP+ are cofactors in a wide variety of enzymatic oxidation-reduction reactions, most notably glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and the electron transport chain.[33] If humans ingest nicotinamide, it will likely undergo a series of reactions that transform it into NAD, which can then undergo a transformation to form NADP+. This method of creation of NAD+ is called a salvage pathway. However, the human body can produce NAD+ from the amino acid tryptophan and niacin without our ingestion of nicotinamide.[34]

NAD+ acts as an electron carrier that mediates the interconversion of energy between nutrients and the cell's energy currency, adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In oxidation-reduction reactions, the active part of the cofactor is the nicotinamide. In NAD+, the nitrogen in the aromatic nicotinamide ring is covalently bonded to adenine dinucleotide. The formal charge on the nitrogen is stabilized by the shared electrons of the other carbon atoms in the aromatic ring. When a hydride atom is added onto NAD+ to form NADH, the molecule loses its aromaticity, and therefore a good amount of stability. This higher energy product later releases its energy with the release of a hydride, and in the case of the electron transport chain, it assists in forming adenosine triphosphate.[35]

When one mole of NADH is oxidized, 158.2 kJ of energy will be released.[35]

Biological role

[edit]Nicotinamide occurs as a component of a variety of biological systems, including within the vitamin B family and specifically the vitamin B3 complex.[10][11] It is also a critically important part of the structures of NADH and NAD+, where the N-substituted aromatic ring in the oxidised NAD+ form undergoes reduction with hydride attack to form NADH.[33] The NADPH/NADP+ structures have the same ring, and are involved in similar biochemical reactions.

Nicotinamide can be methylated in the liver to biologically active 1-Methylnicotinamide when there are sufficient methyl donors.

Food sources

[edit]Nicotinamide occurs in trace amounts mainly in meat, fish, nuts, and mushrooms, as well as to a lesser extent in some vegetables.[36] It is commonly added to cereals and other foods. Many multivitamins contain 20–30 mg of vitamin B3 and it is also available in higher doses.[37]

Compendial status

[edit]Research

[edit]A 2015 trial found nicotinamide to reduce the rate of new nonmelanoma skin cancers and actinic keratoses in a group of people at high risk for the conditions.[40]

Nicotinamide has been investigated for many additional disorders, including treatment of bullous pemphigoid and nonmelanoma skin cancers.[41]

Nicotinamide may be beneficial in treating psoriasis.[42]

There is tentative evidence for a potential role of nicotinamide in treating acne, rosacea, autoimmune blistering disorders, ageing skin, and atopic dermatitis.[41] Nicotinamide also inhibits poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARP-1), enzymes involved in the rejoining of DNA strand breaks induced by radiation or chemotherapy.[43] ARCON (accelerated radiotherapy plus carbogen inhalation and nicotinamide) has been studied in cancer.[44]

Research has suggested nicotinamide may play a role in the treatment of HIV.[45]

Extra-terrestrial occurrence

[edit]Extra-terrestrial nicotinamide has been found in carbonaceous chondrite meteorites.

| Meteorite | Nicotinic acid | Nicotinamide |

|---|---|---|

| Orgueil[46] | 715 ppb | 214 ppb |

| Murray[18] | 626 ppb | 65 ppb |

| Murchison | 2.4 nmol/g[47] 190 ppb[18] | 16 ppb[18] |

| Tagish Lake[18] | 108 ppb | 5 ppb |

References

[edit]- ^ Record in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- ^ Sweetman SC (2011). Martindale: the complete drug reference (37 ed.). London: Pharmaceutical press. p. 2117. ISBN 978-0-85369-933-0. OCLC 1256529676.

- ^ Bender DA (2003). Nutritional Biochemistry of the Vitamins. Cambridge University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-139-43773-8. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 496, 500. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 978-92-4-154765-9.

- ^ a b c British National Formulary: BNF 69 (69th ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 822. ISBN 978-0-85711-156-2.

- ^ Bissett DL, Oblong JE, Berge CA (July 2005). "Niacinamide: A B vitamin that improves aging facial skin appearance". Dermatologic Surgery. 31 (7 Pt 2): 860–5, discussion 865. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31732. PMID 16029679.

- ^ a b c d e f Knip M, Douek IF, Moore WP, Gillmor HA, McLean AE, Bingley PJ, et al. (November 2000). "Safety of high-dose nicotinamide: a review" (PDF). Diabetologia. 43 (11): 1337–45. doi:10.1007/s001250051536. PMID 11126400. S2CID 24763480. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b MacKay D, Hathcock J, Guarneri E (June 2012). "Niacin: chemical forms, bioavailability, and health effects". Nutrition Reviews. 70 (6): 357–66. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00479.x. PMID 22646128.

- ^ a b "Niacinamide Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ a b c "Niacinamide: Indications, Side Effects, Warnings". Drugs.com. 6 June 2017. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b Krutmann J, Humbert P (2010). Nutrition for Healthy Skin: Strategies for Clinical and Cosmetic Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 153. ISBN 978-3-642-12264-4. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017.

- ^ Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE (2012). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 934. ISBN 978-1-4557-5942-2. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- ^ Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d Blum R (2015). "Vitamins, 11. Niacin (Nicotinic Acid, Nicotinamide)". Vitamins, 11. Niacin (Nicotinic Acid, Nicotinamide. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (6th ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1002/14356007.o27_o14.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ a b Schmidberger JW, Hepworth LJ, Green AP, Flitsch SL (2015). "Enzymatic Synthesis of Amides". In Faber K, Fessner WD, Turner NJ (eds.). Biocatalysis in Organic Synthesis 1. Science of Synthesis. Georg Thieme Verlag. pp. 329–372. ISBN 978-3-13-176611-3. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Oba Y, Takano Y, Furukawa Y, Koga T, Glavin DP, Dworkin JP, et al. (April 2022). "Identifying the wide diversity of extraterrestrial purine and pyrimidine nucleobases in carbonaceous meteorites". Nature Communications. 13 (1) 2008. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.2008O. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29612-x. PMC 9042847. PMID 35473908.

- ^ Niren NM (January 2006). "Pharmacologic doses of nicotinamide in the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions: a review". Cutis. 77 (1 Suppl): 11–6. PMID 16871774.

- ^ Tanno O, Ota Y, Kitamura N, Katsube T, Inoue S (September 2000). "Nicotinamide increases biosynthesis of ceramides as well as other stratum corneum lipids to improve the epidermal permeability barrier". The British Journal of Dermatology. 143 (3): 524–31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2000.03705.x. PMID 10971324. S2CID 21874670.

- ^ Draelos ZD, Matsubara A, Smiles K (June 2006). "The effect of 2% niacinamide on facial sebum production". Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 8 (2): 96–101. doi:10.1080/14764170600717704. PMID 16766489. S2CID 36713665.

- ^ Kim J, Ochoa MT, Krutzik SR, Takeuchi O, Uematsu S, Legaspi AJ, et al. (August 2002). "Activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses". Journal of Immunology. 169 (3): 1535–41. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1535. PMC 4636337. PMID 12133981.

- ^ Snaidr VA, Damian DL, Halliday GM (February 2019). "Nicotinamide for photoprotection and skin cancer chemoprevention: A review of efficacy and safety". Experimental Dermatology. 28 (Suppl 1): 15–22. doi:10.1111/exd.13819. PMID 30698874.

- ^ Taylor EC, Crovetti AJ (1957). "Nicotinamide-1-oxide". Organic Syntheses. 37: 63. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.037.0063; Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 704.

- ^ Taylor EC, Crovetti AJ (1957). "2-Chloronicitinonitrile". Organic Syntheses. 37: 12. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.037.0012; Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 166.

- ^ Teague PC, Short WA (1953). "Nicotinonitrile". Organic Syntheses. 33: 52. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.033.0052; Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 706.

- ^ Allen CF, Wolf CN (1950). "3-Aminopyridine". Organic Syntheses. 30: 3. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.030.0003; Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 45.

- ^ Nagasawa T, Mathew CD, Mauger J, Yamada H (July 1988). "Nitrile Hydratase-Catalyzed Production of Nicotinamide from 3-Cyanopyridine in Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 54 (7): 1766–1769. Bibcode:1988ApEnM..54.1766N. doi:10.1128/AEM.54.7.1766-1769.1988. PMC 202743. PMID 16347686.

- ^ Hilterhaus L, Liese A (2007). "Building Blocks". In Ulber R, Sell D (eds.). White Biotechnology. Advances in Biochemical Engineering / Biotechnology. Vol. 105. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 133–173. doi:10.1007/10_033. ISBN 978-3-540-45695-7. PMID 17408083. S2CID 34552222. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ Asano Y (2015). "Hydrolysis of Nitriles to Amides". In Faber K, Fessner WD, Turner NJ (eds.). Biocatalysis in Organic Synthesis 1. Science of Synthesis. Georg Thieme Verlag. pp. 255–276. ISBN 978-3-13-176611-3. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ Petersen M, Kiener A (1999). "Biocatalysis". Green Chem. 1 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1039/A809538H.

- ^ Servi S, Tessaro D, Hollmann F (2015). "Historical Perspectives: Paving the Way for the Future". In Faber NJ, Fessner WD, Turner K (eds.). Biocatalysis in Organic Synthesis 1. Science of Synthesis. Georg Thieme Verlag. pp. 1–39. ISBN 978-3-13-176611-3. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b Belenky P, Bogan KL, Brenner C (January 2007). "NAD+ metabolism in health and disease" (PDF). Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 32 (1): 12–9. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. PMID 17161604. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ Williams AC, Cartwright LS, Ramsden DB (March 2005). "Parkinson's disease: the first common neurological disease due to auto-intoxication?". QJM. 98 (3): 215–26. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hci027. PMID 15728403.

- ^ a b Casiday R, Herman C, Frey R (5 September 2008). "Energy for the Body: Oxidative Phosphorylation". www.chemistry.wustl.edu. Department of Chemistry, Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Rolfe HM (December 2014). "A review of nicotinamide: treatment of skin diseases and potential side effects". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 13 (4): 324–8. doi:10.1111/jocd.12119. PMID 25399625. S2CID 28160151.

- ^ Ranaweera A (2017). "Nicotinamide". DermNet New Zealand (www.dermnetnz.org). DermNet New Zealand Trust. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat (2009). Index, BP 2009 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Japanese Pharmacopoeia (PDF) (15th ed.). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Minocha R, Damian DL, Halliday GM (January 2018). "Melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer chemoprevention: A role for nicotinamide?". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 34 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1111/phpp.12328. PMID 28681504.

- ^ a b Chen AC, Damian DL (August 2014). "Nicotinamide and the skin". The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 55 (3): 169–75. doi:10.1111/ajd.12163. PMID 24635573. S2CID 45745255.

- ^ Namazi MR (August 2003). "Nicotinamide: a potential addition to the anti-psoriatic weaponry". FASEB Journal. 17 (11): 1377–9. doi:10.1096/fj.03-0002hyp. PMID 12890690. S2CID 39752891.

- ^ "Definition of niacinamide". NCI Drug Dictionary. National Cancer Institute. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ Kaanders JH, Bussink J, van der Kogel AJ (December 2002). "ARCON: a novel biology-based approach in radiotherapy". The Lancet. Oncology. 3 (12): 728–37. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00929-4. PMID 12473514.

- ^ Mandavilli A (7 July 2020). "Patient Is Reported Free of H.I.V., but Scientists Urge Caution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Oba Y, Koga T, Takano Y, Ogawa NO, Ohkouchi N, Sasaki K, et al. (21 March 2023). "Uracil in the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu". Nature Communications. 14 (1) 1292. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.1292O. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36904-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10030641. PMID 36944653. S2CID 257641373.

- ^ Glavin DP, Dworkin JP, Alexander CM, Aponte JC, Baczynski AA, Barnes JJ, et al. (2025). "Abundant ammonia and nitrogen-rich soluble organic matter in samples from asteroid (101955) Bennu". Nature Astronomy. 9 (2): 199–210. Bibcode:2025NatAs...9..199G. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02472-9. PMC 11842271. PMID 39990238.

Nicotinamide

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and nomenclature

Nicotinamide, abbreviated as NAM, is the amide derivative of niacin (vitamin B3), a water-soluble vitamin essential for human metabolism.[1] Chemically known as 3-pyridinecarboxamide, it consists of a pyridine ring with a carboxamide group attached at the 3-position and has the molecular formula C6H6N2O.[1] This compound is classified as a pyridinecarboxamide, distinguishing it from other B vitamins by its role in coenzyme synthesis.[1] Unlike niacin, also called nicotinic acid, nicotinamide does not induce skin flushing—a vasodilatory side effect associated with high doses of the acid form—due to differences in their chemical structures and metabolic handling.[7] Both compounds function as precursors to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), a critical coenzyme, but they are not fully interchangeable across all pathways, as niacin exhibits unique lipid-modulating effects at pharmacological doses that nicotinamide lacks.[8] Nicotinamide has been included on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines since 1979, specifically for the treatment of pellagra, a deficiency disease historically linked to niacin shortfall.[9] The term "nicotinamide" originates from a blend of "nicotine" and "amide," referencing its structural relation to the pyridine-based alkaloid in tobacco, though nicotinamide is non-toxic and bears no connection to tobacco's addictive properties.[10]History

Pellagra, a disease characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and often death, was first systematically described in the late 18th century in Spain and Italy, with epidemics emerging in the United States by the early 1900s, particularly among populations reliant on corn-based diets lacking sufficient niacin precursors.[11] In the 1910s, U.S. Public Health Service physician Joseph Goldberger demonstrated through epidemiological studies and controlled experiments on prisoners and orphans that pellagra was not infectious but resulted from dietary deficiencies, specifically linking it to monotonous corn-heavy diets common in the American South that failed to provide adequate tryptophan or niacin.[12] Goldberger's findings, published between 1915 and 1923, shifted medical understanding toward nutritional prevention, though the exact causative nutrient remained unidentified during his lifetime.[13] In 1937, biochemist Conrad Elvehjem at the University of Wisconsin isolated the anti-pellagra factor from liver extracts, identifying nicotinic acid and its amide form, nicotinamide, both effective in treating black tongue disease in dogs, a canine analog to human pellagra.[14] This breakthrough, building on earlier work with coenzyme fractions, confirmed the role of these compounds as the active pellagra-preventive factors, later designated vitamin B3 (with "niacin" coined from "nicotinic acid vitamin" to avoid nicotine associations), and paved the way for their commercial production.[15] During the 1940s, the biosynthetic pathways for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), the coenzyme form of nicotinamide, were elucidated through enzymatic studies, with Arthur Kornberg identifying key synthesis enzymes like nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase in 1948.[16] Concurrently, Otto Warburg and collaborators expanded on their earlier discoveries, detailing NAD+'s critical function as a redox coenzyme in cellular respiration and dehydrogenase reactions, essential for energy metabolism.[17] Following World War II, widespread enrichment of staple foods like flour and bread with nicotinamide and other B vitamins, mandated by U.S. legislation in the early 1940s, dramatically reduced pellagra incidence, leading to its near-eradication in the United States by the late 1940s through improved dietary intake among at-risk populations.[18][19]Chemical properties

Molecular structure

Nicotinamide, with the IUPAC name pyridine-3-carboxamide, is a derivative of pyridine featuring a carboxamide functional group attached at the 3-position.[1] The molecule consists of a six-membered aromatic ring containing one nitrogen atom (pyridine), where the -C(=O)NH₂ group is bonded to the carbon atom meta to the ring nitrogen.[1] This amide linkage (-CONH₂) replaces the carboxylic acid group (-COOH) found in niacin (nicotinic acid), resulting in nicotinamide being neutral and non-acidic, unlike the acidic niacin.[1][20] The canonical SMILES notation for nicotinamide is C1=CC(=CN=C1)C(=O)N, representing the ring connectivity and the amide substituent.[1] Structurally, it can be visualized as a flat, planar pyridine ring with alternating double bonds, the nitrogen at position 1, and the carboxamide protruding from position 3, enabling resonance within the aromatic system.[1] Nicotinamide lacks chiral centers, as confirmed by its defined atom stereocenter count of zero, and its aromatic ring adopts a planar conformation due to sp² hybridization of the ring atoms.[1]Physical and chemical characteristics

Nicotinamide is a white crystalline powder that is odorless.[1] It exhibits high solubility in water (691 g/L at 20 °C), ethanol (660 g/L at 20 °C), and glycerol; it is sparingly soluble in diethyl ether.[1][21][22] The melting point ranges from 128°C to 131°C.[1] Chemically, the pKa of its conjugate acid is approximately 3.3, corresponding to the pyridine nitrogen.[1] Nicotinamide remains stable under neutral conditions but undergoes hydrolysis to nicotinic acid in strongly acidic or basic environments. For analytical purposes, it shows characteristic UV absorption at around 262 nm in alcohol (log ε = 3.4).[1]Synthesis and production

Industrial production

Nicotinamide is primarily produced on an industrial scale through chemical synthesis routes starting from 3-picoline (3-methylpyridine), with the most common method involving gas-phase ammoxidation followed by hydrolysis of the intermediate 3-cyanopyridine.[23] This process achieves high purity levels exceeding 95%, suitable for pharmaceutical and supplement applications.[23] An alternative route directly hydrolyzes 3-cyanopyridine, which can be sourced from other ammoxidation processes.[24] The key ammoxidation step reacts 3-picoline with ammonia and oxygen in a fluidized bed reactor, catalyzed by metal oxides such as vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅) combined with antimony oxide (Sb₂O₅), chromium oxide (Cr₂O₃), and titanium dioxide (TiO₂).[23] The reaction occurs at temperatures of 300–400°C and pressures around 0.5 MPa, selectively converting the methyl group to a cyano group to form 3-cyanopyridine with yields up to 99%.[23] The overall reaction can be represented as: This step is preferred for its efficiency and atom economy in large-scale operations.[24] Subsequent hydrolysis of 3-cyanopyridine to nicotinamide typically employs alkaline conditions using 10% sodium hydroxide at 190°C and 1.5–2 MPa, followed by purification via ion exchange and crystallization to isolate the amide product.[23] The process yields nicotinamide with minimal impurities, and the main byproduct is water, contributing to its relatively low environmental footprint compared to older methods.[23] Major global producers include Lonza Group and BASF SE.[25] Overall worldwide production exceeded 75,000 metric tons as of 2024, directed toward supplements, animal feed, and medicinal formulations.[26] Production has grown significantly due to increasing demand in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. Environmental considerations in nicotinamide production have driven shifts toward catalytic ammoxidation routes since the early 2000s, phasing out cyanide-intensive processes that generated hazardous byproducts like NOx from nitric acid oxidations. Modern methods emphasize byproduct management and greener catalysis to minimize waste, with water as the predominant effluent and reduced emissions of volatile organics.[23]Biosynthesis

Nicotinamide is primarily synthesized in living organisms through two main enzymatic pathways: the de novo pathway and the salvage pathway, both contributing to the production of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD⁺), from which nicotinamide is derived upon degradation.[27] In mammals, the de novo pathway begins with the amino acid tryptophan and proceeds via the kynurenine pathway, where tryptophan is oxidized to N-formylkynurenine by tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase in the liver, followed by subsequent steps involving kynurenine 3-monooxygenase and kynureninase to form anthranilic acid and eventually quinolinic acid.[28] Quinolinic acid is then converted to nicotinic acid mononucleotide by quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase, leading to nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide and finally NAD⁺, which can be hydrolyzed to release nicotinamide.[27] This pathway accounts for the majority of de novo NAD⁺ synthesis in mammals, with approximately 60 mg of tryptophan yielding about 1 mg of niacin equivalent (nicotinamide or nicotinic acid), and typical daily dietary tryptophan intake supporting around 10-15 mg of such equivalents.[29] The salvage pathway recycles nicotinamide generated from NAD⁺ degradation, which occurs through enzymatic hydrolysis by sirtuins, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases, and CD38 during cellular processes like DNA repair and signaling.[27] The rate-limiting step is catalyzed by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which uses phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) to convert nicotinamide into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN).[30] NMN is then adenylated by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT) to form NAD⁺, closing the recycling loop and preventing nicotinamide accumulation.[31] This pathway is predominant in most tissues, especially under conditions of limited de novo synthesis, and can sustain up to 85% of NAD⁺ pools in mammals by reutilizing nicotinamide from dietary or endogenous sources.[27] In microorganisms, nicotinamide biosynthesis can be enhanced through metabolic engineering, particularly in bacteria like Escherichia coli. Engineered strains overexpressing NAMPT homologs (such as NadV) and optimizing PRPP availability have achieved high-yield fermentation, with NMN production reaching up to 16.2 g/L in bioreactors under optimized conditions like supplemented nicotinamide and lactose media.[32] These microbial systems leverage the salvage pathway for efficient biotransformation, offering scalable production alternatives to chemical synthesis.[33] Biosynthesis of nicotinamide is tightly regulated to maintain cellular NAD⁺ homeostasis, with NAMPT and NMNAT as key control points. High NAD⁺ levels indirectly inhibit the pathway through feedback mechanisms, including allosteric modulation of NAMPT by energy status (e.g., AMP/ATP ratios) and transcriptional repression of salvage enzymes during NAD⁺ abundance.[34] In mammals, the de novo kynurenine pathway is primarily active in the liver and inhibited by excess NAD⁺ via reduced expression of tryptophan dioxygenase, while the salvage pathway responds to NAD⁺ depletion by upregulating NAMPT under stress conditions like inflammation or aging.[27]Biological and metabolic roles

Coenzyme functions

Nicotinamide acts as a key precursor in the biosynthesis of the essential coenzymes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD⁺) and its phosphorylated derivative, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP⁺), which are critical for cellular redox reactions and metabolism. Through the salvage pathway, nicotinamide is first converted to nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) by the enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), a rate-limiting step that recycles nicotinamide derived from NAD⁺ consumption. NMN is then transformed into NAD⁺ by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNATs), a family of enzymes localized in different cellular compartments to ensure efficient NAD⁺ production.[27][35] NAD⁺ primarily functions as an electron acceptor in catabolic processes, undergoing reduction to NADH by accepting a hydride ion (H⁻) from substrates in dehydrogenase reactions. This redox capability is exemplified by the half-reaction: with a standard reduction potential (E°') of -0.32 V at pH 7, enabling the transfer of electrons to the mitochondrial electron transport chain.[36] NAD⁺-dependent dehydrogenases facilitate hydride transfer in central metabolic pathways, including glycolysis (e.g., glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (e.g., isocitrate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase), and β-oxidation of fatty acids, ultimately supporting ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation. Approximately 500 enzymes across these and other pathways rely on NAD⁺/NADH as a cofactor for maintaining cellular energy homeostasis.[37][27] In contrast, NADP⁺, formed by phosphorylation of NAD⁺ via NAD⁺ kinase, predominates in anabolic reactions where its reduced form, NADPH, supplies reducing equivalents. NADPH is crucial for biosynthetic processes such as fatty acid synthesis, where it powers the reductive steps catalyzed by fatty acid synthase, as well as cholesterol and nucleotide synthesis. This distinction allows cells to compartmentalize redox balance, with NAD⁺/NADH favoring oxidation and NADP⁺/NADPH supporting reduction in pathways that build complex molecules.[27]Deficiency effects

Nicotinamide deficiency, also known as niacin deficiency, leads to the clinical syndrome pellagra, characterized by the classic triad of symptoms: dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. Dermatitis manifests as a photosensitive rash, typically appearing as symmetrical, erythematous lesions on sun-exposed areas such as the face, neck (often forming a "Casal's necklace"), hands, and feet, which can progress to bullae, scaling, and hyperpigmentation in severe cases. Diarrhea presents as profuse, watery stools, sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and glossitis. Dementia involves initial neuropsychiatric symptoms like irritability, anxiety, poor concentration, and depression, potentially advancing to confusion, hallucinations, delirium, and coma if untreated. Collectively, these are referred to as the "4 Ds" of pellagra—dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and death—which can occur if the deficiency remains unaddressed.[38][39] The underlying mechanisms of pellagra stem from depletion of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), a critical coenzyme derived from nicotinamide, which impairs cellular energy metabolism and other vital processes. NAD+ depletion disrupts over 500 enzymatic reactions, including those essential for ATP production through glucose, fat, and protein oxidation, leading to widespread metabolic dysfunction, particularly in high-energy tissues like the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system.[38][37] Risk factors for nicotinamide deficiency include diets predominantly composed of maize or other staples low in bioavailable niacin and tryptophan (the amino acid precursor to niacin), as maize contains niacin in a bound form with limited digestibility unless processed with alkali. Chronic alcoholism increases susceptibility by promoting poor nutrition, impairing intestinal absorption, and interfering with tryptophan conversion to niacin. Genetic conditions like Hartnup disease, which impair tryptophan absorption in the intestines and kidneys, also heighten risk by limiting the substrate for endogenous niacin synthesis.[38][39] Subclinical nicotinamide deficiency can manifest as nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, depression, and irritability, often preceding overt pellagra and affecting quality of life without the classic diagnostic signs. While pellagra has been largely eradicated in industrialized nations through food fortification, it persists in developing regions, particularly among vulnerable populations like refugees and those in low-income countries with maize-dependent diets; estimates suggest millions remain at risk globally, with historical outbreaks affecting tens of thousands in emergency settings.[38][39][40]Sources and intake

Dietary sources

Nicotinamide, a form of vitamin B3, is obtained from dietary sources primarily as niacin equivalents, which include preformed niacin (nicotinic acid and nicotinamide) and tryptophan that the body converts to nicotinamide at a ratio of approximately 60 mg tryptophan yielding 1 mg niacin equivalent. Animal-based foods are rich sources, providing highly bioavailable forms mainly as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and NAD phosphate (NADP). Beef, chicken, shrimp, fish like salmon and tuna, and milk (especially fresh milk, rich in nicotinamide riboside (NR)) are examples that help raise NAD+ levels. Beef liver contains about 17.5 mg niacin per 100 g, while poultry such as chicken breast offers around 12 mg per 100 g, and fish like tuna provides approximately 10–13 mg per 100 g.[7][41] Plant-based foods contribute lower amounts of niacin equivalents, often in less bioavailable forms bound to plant matrices. Brewer's yeast (including beer yeast products) is an exception, delivering up to 40 mg per 100 g, and peanuts supply about 12 mg per 100 g; whole grains also provide moderate contributions. Green vegetables generally provide 0.5–2 mg per 100 g, with examples like spinach at 0.7 mg per 100 g and broccoli at 0.6 mg per 100 g. The body's conversion of tryptophan from protein-rich plants further supports niacin status.[42][41] The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for niacin equivalents is 16 mg per day for adult men and 14 mg per day for adult women, accounting for both preformed niacin and tryptophan conversion. Bioavailability varies by food type; animal sources offer near-complete absorption (over 90%), while plant sources range from 30–70%, with niacin in some grains like corn being particularly low due to binding unless processed. In regions relying on corn as a staple, such as parts of Latin America and historically the southern United States, niacin intake is limited without nixtamalization—a traditional alkali treatment that significantly enhances bioavailability through hydrolysis of bound forms.[7][42] In balanced diets worldwide, average daily niacin intake typically ranges from 20–30 mg, exceeding the RDA and reflecting contributions from diverse foods; for instance, U.S. adults consume about 31 mg for men and 21 mg for women.[7][42]| Food Category | Example | Niacin Equivalents (mg/100 g) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal (Liver) | Beef liver, cooked | 17.5 | USDA FoodData Central |

| Animal (Fish) | Tuna, canned in water | 10–13 | USDA FoodData Central |

| Animal (Poultry) | Chicken breast, cooked | 12 | NIH ODS |

| Plant (Yeast) | Brewer's yeast, dried | 40 | Linus Pauling Institute |

| Plant (Nuts) | Peanuts, raw | 12 | USDA FoodData Central |

| Plant (Vegetables) | Spinach, raw | 0.7 | USDA FoodData Central |