Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Azanide

View on Wikipedia | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈæzənaɪd/ |

| IUPAC name

Azanide

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| NH−2 | |

| Molar mass | 16.023 g·mol−1 |

| Conjugate acid | Ammonia |

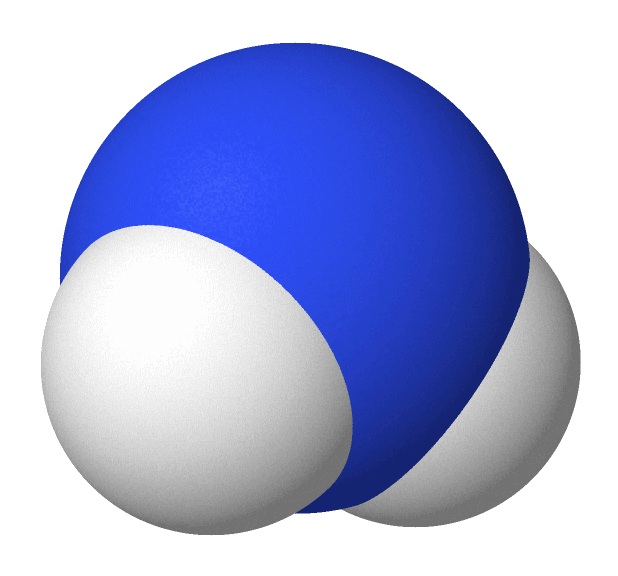

| Structure | |

| Bent | |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

|

Related isoelectronic

|

water, fluoronium |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Azanide is the IUPAC-sanctioned name for the anion NH−2. The term is obscure; derivatives of NH−2 are almost invariably referred to as amides,[1][2][3] despite the fact that amide also refers to the organic functional group –C(=O)−NR2. The anion NH−2 is the conjugate base of ammonia, so it is formed by the self-ionization of ammonia. It is produced by deprotonation of ammonia, usually with strong bases or an alkali metal. Azanide has a H–N–H bond angle of 104.5°, nearly identical to the bond angle in the isoelectronic water molecule.

Alkali metal derivatives

[edit]The alkali metal derivatives are best known, although usually referred to as alkali metal amides. Examples include lithium amide, sodium amide, and potassium amide. These salt-like solids are produced by treating liquid ammonia with strong bases or directly with the alkali metals (blue liquid ammonia solutions due to the solvated electron):[1][2][4]

- 2 M + 2 NH3 → 2 MNH2 + H2, where M = Li, Na, K

Silver(I) amide (AgNH2) is prepared similarly.[3]

Transition metal complexes of the amido ligand are often produced by salt metathesis reaction or by deprotonation of metal ammine complexes.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bergstrom, F. W. (1940). "Sodium Amide". Organic Syntheses. 20: 86. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.020.0086.

- ^ a b P. W. Schenk (1963). "Lithium amide". In G. Brauer (ed.). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Academic Press. p. 454.

- ^ a b O. Glemser, H. Sauer (1963). "Silver Amide". In G. Brauer (ed.). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Academic Press. p. 1043.

- ^ Greenlee, K. W.; Henne, A. L. (1946). "Sodium Amide". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 2. pp. 128–135. doi:10.1002/9780470132333.ch38. ISBN 9780470132333.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)