Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Barotropic fluid

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2025) |

In fluid dynamics, a barotropic fluid is a fluid whose density is a function of pressure only.[1] The barotropic fluid is a useful model of fluid behavior in a wide variety of scientific fields, from meteorology to astrophysics.

The density of most liquids is nearly constant (isopycnic), so it can be stated that their densities vary only weakly with pressure and temperature. Water, which varies only a few percent with temperature and salinity, may be approximated as barotropic. In general, air is not barotropic, as it is a function of temperature and pressure; but, under certain circumstances, the barotropic assumption can be useful.

In astrophysics, barotropic fluids are important in the study of stellar interiors or of the interstellar medium. One common class of barotropic model used in astrophysics is a polytropic fluid. Typically, the barotropic assumption is not very realistic.

In meteorology, a barotropic atmosphere is one that for which the density of the air depends only on pressure, as a result isobaric surfaces (constant-pressure surfaces) are also constant-density surfaces. Such isobaric surfaces will also be isothermal surfaces, hence (from the thermal wind equation) the geostrophic wind will not vary with depth. Hence, the motions of a rotating barotropic air mass is strongly constrained. The tropics are more nearly barotropic than mid-latitudes because temperature is more nearly horizontally uniform in the tropics.

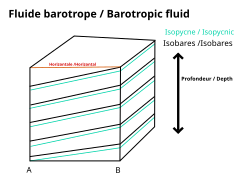

A barotropic flow is a generalization of a barotropic atmosphere. It is a flow in which the pressure is a function of the density only and vice versa. In other words, it is a flow in which isobaric surfaces are isopycnic surfaces and vice versa. One may have a barotropic flow of a non-barotropic fluid, but a barotropic fluid will always follow a barotropic flow. Examples include barotropic layers of the oceans, an isothermal ideal gas or an isentropic ideal gas.

A fluid which is not barotropic is baroclinic, i. e., pressure is not the only factor to determine density. For a barotropic fluid or a barotropic flow (such as a barotropic atmosphere), the baroclinic vector is zero.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Shames, Irving H. (1962). Mechanics of Fluids. McGraw-Hill. p. 159. LCCN 61018731. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

If is expressible as a function of only, that is, , the in Eq. 5-66 is integrable. Fluids having this characteristic are called barotropic fluids.

- James R Holton, An introduction to dynamic meteorology, ISBN 0-12-354355-X, 3rd edition, p77.

- Marcel Lesieur, "Turbulence in Fluids: Stochastic and Numerical Modeling", ISBN 0-7923-0645-7, 2e.

- David Tritton, "Physical Fluid Dynamics", ISBN 0-19-854493-6.