Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

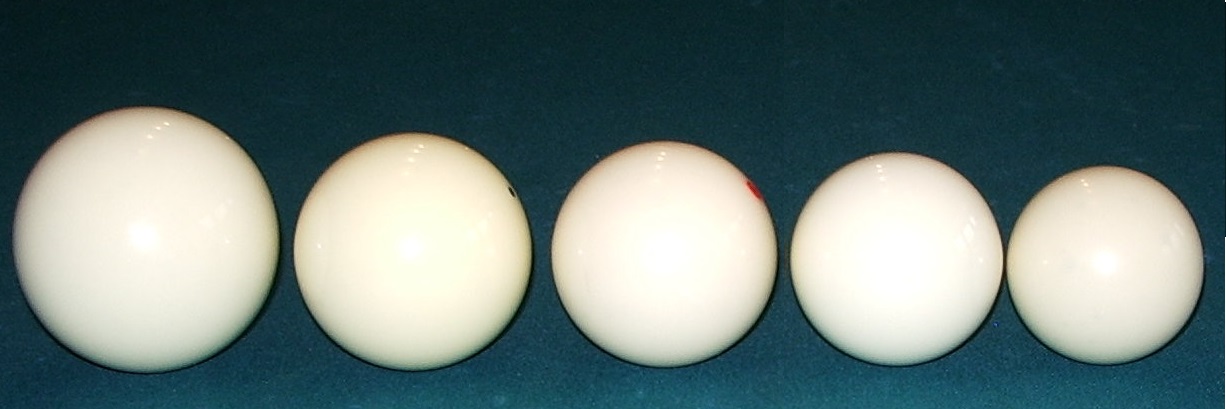

Billiard ball

View on Wikipedia

- Russian pyramid and kaisa—68 mm (2+11⁄16 in)

- Carom—61.5 mm (2+7⁄16 in)

- International pool—57.15 mm (2+1⁄4 in)

- Snooker—52.5 mm (2+1⁄16 in)

- British-style pool—51 mm (2 in)

A billiard ball is a small, hard ball used in cue sports, such as carom billiards, pool, and snooker. The number, type, diameter, color, and pattern of the balls differ depending upon the specific game being played. Various particular ball properties such as hardness, friction coefficient, and resilience are important to accuracy.

History

[edit]

Early balls were made of various materials, including wood and clay (the latter remaining in use well into the 20th century). Although affordable ox-bone balls were in common use in Europe, elephant ivory was favored since at least 1627 until the early 20th century;[1]: 17 the earliest known written reference to ivory billiard balls is in the 1588 inventory of Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk.[2] Dyed and numbered balls appeared around the early 1770s.[1]: 17 By the mid-19th century, elephants were being slaughtered for their ivory at an alarming rate, just to keep up with the demand for high-end billiard balls – no more than eight balls could be made from a single elephant's tusks.[citation needed] The billiard industry realized that the supply of elephants (their primary source of ivory) was endangered, as well as dangerous to obtain (the latter an issue of notable public concern at the turn of the 19th century).[1]: 17 Inventors were challenged to come up with an alternative material that could be manufactured, with a US$10,000 (worth approximately $236,225 in 2024[3]) prize being offered by a New York supplier.[1]: 17

Although not the first artificial substance to be used for the balls (e.g. Sorel cement, invented in 1867, was marketed as an artificial ivory), John Wesley Hyatt patented an "ivory imitation" composite made of nitrocellulose, camphor, and ground cattle bone on May 4, 1869 (US patent 89582, the first US billiard ball patent). The material was a success, and was sold as Bonzoline, Crystalate, Ivorylene until the 1960s, and was used by prominent professional players such as John Roberts Jr (1847–1919), Charles Dawson (1866–1921), and Walter Lindrum (1898–1960). The ivory substitute was one of the most significant early reinforced plastics; induced the global growth of billiards, pool, and snooker; and helped create a modern idea that the artificial can surpass the natural.[4][5] It is unclear if the cash prize was ever awarded, and there is no evidence suggesting he did in fact win it.[1]: 17 [6]

However, Hyatt's composite had problems. One of the most relevant is cellulose nitrate flammability, not because of making the billiard balls explode, as is often claimed, but because of the dangers of handling it in its pure form during manufacturing. Another problem was related to camphor mass exploitation, leading to the devastation of Taiwan's forests and displacement of indigenous communities.[4][7] Subsequently, the industry experimented with various other synthetic materials for billiard balls such as Bakelite, acrylic, and other plastic compounds.

The exacting requirements of the billiard ball are met today with balls cast from plastic materials that are strongly resistant to cracking and chipping. Currently Saluc, under the brand name Aramith and other private labels, manufactures phenolic resin balls.[8][9] Other plastics and resins such as polyester (similar to those used for bowling balls) and clear acrylic are also used.

Ivory balls remained in use in artistic billiards competition until the late 20th century.[1]: 17

Types

[edit]Carom and English billiards

[edit]

In the realm of carom billiards games, three balls are used to play most games on pocketless billiards tables. Carom balls are not numbered, and are 61–61.5 mm (approximately 2+13⁄32 in) in diameter, and a weight ranging between 205 and 220 grams (7.2 and 7.8 oz) with a typical weight of 210 g (7.5 oz).[10] They are typically colored as follows:

- White: cue ball for the first player

- Yellow: cue ball for the second player (historically this was white with a distinguishing spot)

- Red: the object ball (four-ball uses an extra object ball, usually blue).

English billiards uses the same number of balls as carom billiards, but the same size as snooker balls, as the game is played on the same size table as snooker. Each player uses a separate cue ball, with modern English billiards sets using one white ball with red spots and the other being yellow with red spots. The object ball used is red, but in some additions, it is red with white spots.

Pool

[edit]

| 1 | Solid Yellow | |||

| 2 | Solid Blue | |||

| 3 | Solid Red | |||

| 4 | Solid Purple | |||

| 5 | Solid Orange | |||

| 6 | Solid Green | |||

| 7 | Solid Maroon | |||

| 8 | Solid Black | |||

| 9 | Yellow Stripe | |||

| 10 | Blue Stripe | |||

| 11 | Red Stripe | |||

| 12 | Purple Stripe | |||

| 13 | Orange Stripe | |||

| 14 | Green Stripe | |||

| 15 | Maroon Stripe | |||

| • | White | |||

Pool balls are used to play various pool games, such as eight-ball, nine-ball, and straight pool. These balls, the most widely used throughout the world, are smaller than carom billiards balls, and larger than those for snooker. According to World Pool-Billiard Association equipment specifications, the weight may be from 5+1⁄2 to 6.0 oz (160–170 g) with a diameter of 2+1⁄4 in (57 mm), plus or minus 0.005 in (0.127 mm).[11][12]

The balls are numbered and colored as in the table show here. Balls 1 through 7 are the suit of solids and 9 through 15 are the stripes. The 8 ball is not considered part of either suit. Striped balls were introduced around 1889.[1]: 246

Rotation games do not distinguish between solids and stripes, but rather use the numbering on the balls to determine which object ball must be pocketed. In other games such as straight pool neither type of marking is of any consequence.

Some balls used in televised pool games are colored differently in order to make them more distinguishable on television monitors. Most commonly, the dark purple used on the 4 and 12 balls is replaced by pink to make it easier to distinguish the 4 from the black 8 ball, and similarly the 7 and 15 balls use a lighter brown color instead of a deep maroon. Other, less common color substitutions are also found, dependent on manufacturer. These sets often have a cue ball with multiple spots on its surface so that spin placed on it is evident to viewers.

Baseball billiards uses 21 balls instead of 15, adding 6 extra striped balls, with the 16 ball being black and the 17 through 21 balls being the same colors as the 9 through 13 balls.

Coin-operated pool tables, such as those found at bowling alleys, arcades, or bars/pubs, may use a slightly different-sized cue ball, so that the cue ball can be separated from object balls by the table's ball return mechanism and delivered into its own ball return. Such different sized cue balls are considered less than ideal because they change the dynamics of the equipment. Other tables use a system where a magnet pulls a cue ball with a thin layer of metal embedded inside away from the object ball collection chamber and into the cue ball return, allowing the cue ball to more closely match the object balls in size and weight. More recently, optical systems that recognize the cue ball, which is more translucent than the other balls due to its solid white color, and separate it mechanically have been developed.

Blackball and British-style eight-ball pool

[edit]In British-style eight-ball pool and its blackball variant, fifteen object balls are used, but fall into two unnumbered groups, the reds (or less commonly blues) and yellows, with a white cue ball, and black 8 ball.

Aside from the 8, shots are not called since there is no reliable way to identify particular balls to be pocketed. Because they are unnumbered, they are wholly unsuited to certain pool games, such as nine-ball, in which ball order is important. They are typically smaller than the American-style balls; the most common object ball diameters are 2 in (51 mm) and 2+1⁄16 in (52 mm).[13] The yellow-and-red sets are sometimes referred to as "casino sets" as they were developed to make identification of suits easier for spectators at eight-ball championships often held in casinos.[1]: 45 Such sets were sold by the Brunswick–Balke–Collender Co. as early as 1908.[1]: 24 Similar to standard pool balls, there are also special sets designed for televised games; these sets have a black-striped 8 ball, and a spotted cue ball.

Snooker

[edit]| Colour | Value |

|---|---|

| White | 0 points |

| Red | 1 point |

| Yellow | 2 points |

| Green | 3 points |

| Brown | 4 points |

| Blue | 5 points |

| Pink | 6 points |

| Black | 7 points |

Ball sets for snooker consist of twenty-two balls in total, arranged as a rack of 15 unmarked red balls, six colour balls placed at various predetermined spots on the table, and a white cue ball. The colour balls are sometimes numbered with their point values in the style of pool balls for the home market.

Snooker balls are standardized at 52.5 mm (2+1⁄16 in) in diameter within a tolerance of plus or minus 0.05 mm (0.002 in). No standard weight is defined, but all balls in the set must be the same weight within a tolerance of 3 g (0.11 oz).[14] Snooker sets are also available with considerably smaller-than-regulation balls (and even with ten instead of fifteen reds) for play on smaller tables (down to half-size), and are sanctioned for use in some amateur leagues. Sets for American snooker are typically 2+1⁄8 in (54.0 mm), with numbered colour balls.

The set of eight colours used for snooker balls (including white) are thought to be derived from croquet, which uses the same set of colors. Snooker was invented in 1884 by British Army officers stationed in India. Croquet reached its peak popularity at the same time, particularly among people in the same social context. There are many other similarities between croquet and snooker, which when taken together, suggest that the derivation of the latter owes much to the existence of the former.[15]

Some snooker variations use extra balls:

- Snooker plus - uses an orange ball with a value of 8 points and a purple ball with a value of 10 points.

- Power Snooker - uses a white ball with red stripe (similarly to the 11 ball in Pool) which doubles all the ball values for 30 seconds.

- Tenball - uses a yellow ball with black cross which values 10 points.

- SnooPool - uses a violet ball ("Amethyst"), a gray ball ("Graphite") and a gold ball. Since this game is a mix of Snooker and Pool, the balls have no points of values, while the gold ball replaces the black ball in grand finals.

Other games

[edit]Various other games have their own variants of billiard balls.

Russian pyramid uses a set of fifteen numbered white balls and a red or yellow cue ball that are even larger than carom billiards balls at 68 millimetres (2+11⁄16 in). Kaisa has the same pocket and ball dimensions but uses only five balls: one yellow, two red and two white cue balls, one for each player.[16]

Bumper pool requires four white and four red object balls, and two special balls, one red with a white circle and the other white with a red circle; all are usually 2+1⁄8 inches (54 mm) in diameter. Bar billiards uses six or seven white balls (depending on regional variations) and one red ball 1+7⁄8 in (48 mm) in diameter.

Novelty balls

[edit]

There is a market for specialty cue balls and even entire ball sets, featuring sports team logos, cartoon characters, animal pelt patterns, or other non-standard decorations.

Entrepreneurial inventors also supply a variety of novelty billiard games with unique rules and balls, some with playing card markings, others with stars and stripes, and yet others in sets of more than thirty balls in several suits. Marbled-looking and glittery materials are also popular for home tables. There are even blacklight sets for playing in near-dark. There are also practical joke cue and 8 balls, with off-center weights in them that make their paths curve and wobble. Miniature sets in various sizes (typically +2⁄3 or +1⁄2 of normal size) are also commonly available, primarily intended for undersized toy tables. Even an egg-shaped ball has been patented[17] and marketed under such names as Bobble Ball and Tag Ball.

In popular culture

[edit]

The 8 ball is frequently used in Western, especially American, culture as an element of T-shirt designs, album covers and names, tattoos, household goods like paperweights and cigarette lighters, belt buckles, etc. A classic toy is the Magic 8 Ball "oracle".

The term "8-ball" is also slang both for 1⁄8 ounce (3.5 g) of cocaine or crystal meth, and for a bottle of Olde English 800 malt liquor. It has also been used to refer to African-Americans, particularly those of darker skin tones, as in the films Show Boat and Full Metal Jacket. The expression "behind the eight [ball]" is used to indicate a dilemma from which it is difficult to extricate oneself. The term derives from the game kelly pool.[18][19][20][21][22]

Because the collisions between billiard balls are nearly elastic, and the balls roll on a surface that produces low rolling friction, their behavior is often used to illustrate Newton's laws of motion. Idealized, frictionless billiard balls are a staple of mathematical theorems and physics models, and figure in dynamical billiards, scattering theory, Lissajous knots, billiard ball computing, and reversible cellular automata, Polchinski's paradox, contact dynamics, collision detection, the illumination problem, atomic ultracooling, quantum mirages, and elsewhere in these fields.

"Billiard balls" or "pool balls" is the name given to balls used in stage magic tricks, especially the classic "multiplying billiard balls". Though derived from real billiard balls, today they are usually smaller, for easier manipulation and hiding, but not so small and light that they are difficult to juggle, as the magic and juggling disciplines have often overlapped since their successful combination by pioneers like Paul Vandy.

The phrase "as smooth as a billiard ball" is sometimes applied to describe a bald person, and the term "cue ball" is also slang for someone who sports a shaved head.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shamos, Mike (1999). The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 9781558217973 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Everton, Clive (1986). The History of Snooker and Billiards. Haywards Heath, England: Partridge Press. p. 8. ISBN 1-85225-013-5.

11 balls of yvery

This is a revised version of The Story of Billiards and Snooker, 1979. - ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ a b Neves, Artur; Friedel, Robert; Melo, Maria J.; Callapez, Maria Elvira; Vicenzi, Edward P.; Lam, Thomas (1 November 2023). "Best billiard ball in the 19th century: Composite materials made of celluloid and bone as substitutes for ivory". PNAS Nexus. 2 (11). doi:10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad360. ISSN 2752-6542. PMC 10651075.

- ^ Neves, Artur. "First successful substitutes for ivory billiard balls were made with celluloid reinforced with ground cattle bone". Phys.org. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Hyatt". Plastiquarian.com. London: Plastics Historical Society. 2002. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Altman, Rebecca (2 July 2021). "The myth of historical bio-based plastics". Science. 373 (6550): 47–49. doi:10.1126/science.abj1003. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ "Aramith". Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- ^ "History". brunswickbilliards.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "World Rules of Carom Billiard" (PDF). UMB.org. Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium: Union Mondiale de Billard. 1 January 1989. Chapter II ("Equipment"), Article 12 ("Balls, Chalk"), Section 2. Retrieved 27 November 2023. Officially but somewhat poorly translated version, from the French original.

- ^ "Recommended Equipment Specifications". WPAPool.com. World Pool-Billiard Association. November 2001. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ BCA Rules Committee (2004). Billiards: The Official Rules and Records Book. Colorado Springs: Billiard Congress of America. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-878493-14-9.

- ^ "Section 5: Table and Equipment Specification". WEPF.org. World Eight-ball Pool Federation. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Equipment". WorldSnooker.com. London: World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ "An Introduction to Croquet: A Brief History". Croquet.org.uk. Croquet Association. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Russian Billiards". CuesUp.com. 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ U.S. Patent No. 7,468,002

- ^ Shamos, Michael Ian (1993). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons & Burford. pp. 85, 128, and 168. ISBN 1-55821-219-1 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jewett, Bob (February 2002). "8-Ball Rules: The many different versions of one of today's most common games". Billiards Digest: 22–23.

- ^ Hickok, Ralph (2001). "Sports History: Pocket Billiards". HickokSports.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2002. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ Shamos, Mike (2019) [2001]. "About the Industry: A Brief History of the Noble Game of Billiards". Billiard Congress America. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- ^ Mizerak, Steve; Panozzo, Michael E. (1990). Steve Mizerak's Complete Book of Pool. Chicago: Contemporary Books. pp. 127–128. ISBN 0-8092-4255-9 – via Internet Archive.

Patents

[edit]- U.S. patent 50,359—Billiard ball c. 1865

- U.S. patent 76,765—Billiard ball c. 1868

- U.S. patent 88,634—Billiard ball c. 1869

- U.S. patent 114,945—Billiard ball c. 1871

Billiard ball

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Early Materials

The earliest precursors to billiard balls appeared in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, crafted from rudimentary materials such as wood, clay, or stone for outdoor lawn games that evolved into indoor table variants.[3][1] These materials suffered from poor durability, irregular shapes, and inconsistent rolling behavior, limiting gameplay precision on emerging enclosed tables.[4] By the 17th century, elephant ivory from tusks became the dominant material, valued for its natural smoothness, high density providing stable weight and rebound, and the distinctive acoustic "click" produced during collisions.[4][2] African ivory was particularly prized over Indian variants for more uniform density, though natural tusk imperfections often led to rejected balls with defects affecting sphericity and performance.[9][10] Intensifying demand in the 19th century, driven by billiards' popularity among nobility and expanding markets, exacerbated overhunting of elephants, creating acute ivory shortages and escalating costs by the 1860s.[11][12] This scarcity prompted early experiments with composite alternatives, such as mixtures incorporating bone dust for improved density and moldability, yet these struggled to replicate ivory's consistent elasticity and uniformity without cracking or warping under play stresses.[13][14]Transition to Synthetics

in premium grades and diameter variations limited to ±0.003 inches (0.076 mm).[21] Following World War II, polyester and epoxy resins gained traction for recreational billiard balls due to their affordability and ease of manufacturing, yet phenolic resin retained preference in elite competition for its superior hardness and longevity, enduring over 50 times more impacts without deformation compared to polyester counterparts.[22][23] These properties yield more predictable energy transfer during collisions, with coefficients of restitution approaching 0.95, enhancing shot accuracy and reducing cloth wear from friction.[24] Contemporary refinements, including automated precision polishing and multi-criteria inspection protocols evaluating density, balance, and surface brilliance, have minimized mass discrepancies to under 0.2 grams per set while standardizing global performance metrics for reduced gameplay variance.[25] Such controls, implemented since the late 20th century and refined into the 21st, support empirical data showing phenolic balls maintain structural integrity across thousands of hours of play, outperforming earlier synthetics in elasticity retention.[26]Materials and Construction

Properties of Key Materials

Ivory, derived from elephant tusks, exhibits a density of 1.7 to 1.9 g/cm³, varying with tusk characteristics such as age and location.[27] This material demonstrates high elasticity essential for rebound in collisions, though early synthetics struggled to replicate this trait fully.[28] Its anisotropic structure, arising from the directional alignment of dentin tubules in the tusk, results in inconsistent hardness and elasticity across orientations, which can introduce variability in ball response during play. Such inconsistencies stem from the natural composite nature of ivory, comprising hydroxyapatite crystals in an organic matrix, leading to grain-dependent mechanical behavior. Celluloid, an early nitrocellulose-based synthetic, offered a density around 1.4 g/cm³ but suffered from high flammability, with ignition risks during manufacturing and exaggerated reports of spontaneous combustion under impact.[5] [29] This material's lower density relative to ivory contributed to accelerated surface wear under repeated friction and impacts, as its softer composition eroded faster than denser alternatives.[13] Bakelite, a phenol-formaldehyde resin precursor to modern synthetics, similarly featured a density of approximately 1.3-1.4 g/cm³ and improved durability over celluloid by resisting flammability and explosion, though it still exhibited limitations in long-term hardness retention.[1] Modern phenolic resins, such as those used in premium billiard balls, achieve densities from 1.69 to 1.87 g/cm³, closely approximating ivory's mass for consistent momentum.[21] These thermoset materials provide high hardness and impact resistance, withstanding over 50 times more collisions than polyester alternatives before significant degradation.[22] Their low coefficient of friction against cloth, approximately 0.2, minimizes energy loss and cloth wear while enabling predictable spin control due to uniform surface vitrification.[30] Polyester resins, often used in lower-cost balls, are softer and more susceptible to chipping under edge impacts, generating higher friction that accelerates table cloth burnout.[26][22]| Material | Density (g/cm³) | Hardness/Impact Resistance | Friction Coefficient (on cloth) | Notable Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ivory | 1.7-1.9 | High elasticity; anisotropic variations | Not quantified for balls | Directional inconsistencies |

| Celluloid | ~1.4 | Moderate; prone to wear | Higher due to surface erosion | Flammability; faster degradation |

| Phenolic Resin | 1.69-1.87 | High; >50x impacts vs. polyester | ~0.2 | None primary for play |

| Polyester | ~1.3-1.4 | Lower; chips easily | Higher; increases cloth wear | Softer surface; quicker chipping |

Comparative Performance

Phenolic resin billiard balls demonstrate superior uniformity in energy transfer during collisions, with coefficients of restitution measured between 0.92 and 0.98, enabling consistent 92-98% elastic rebound and minimizing energy loss variability observed in natural ivory balls due to inherent material inconsistencies in density and hardness.[30][31] Ivory's organic composition leads to greater shot-to-shot differences, increasing the incidence of suboptimal "dead" rebounds in prolonged sessions, whereas phenolic's engineered homogeneity supports reliable performance across thousands of impacts.[3] In terms of spin retention, phenolic balls maintain precise control and reduced friction over time, attributed to their harder surface and thermal stability, outperforming polyester alternatives that exhibit earlier inconsistencies in roll and grip after repeated use.[26] This material advantage stems from phenolic's resistance to surface degradation, preserving spin dynamics essential for advanced cueing techniques.[32] Durability tests indicate phenolic balls endure up to five times longer than polyester under professional wear, withstanding approximately 400,000 collisions or spanning 40 years of heavy play while retaining polish and balance.[33][34] Polyester balls, by contrast, degrade faster, typically lasting around eight years before noticeable pitting and imbalance occur, limiting their suitability for high-stakes environments.[34] Criticisms of synthetic materials, such as their non-biodegradability and perceived lack of tactile authenticity compared to ivory, are outweighed by empirical performance gains; acoustic analyses reveal synthetic collisions produce comparable high-frequency "clicks" in the 500 Hz to 10 kHz range, debunking claims of a "soulless" feel through objective sound profile matching.[35] The shift to phenolics reflects causal priorities of consistency and longevity over tradition, with scalability enabling standardized quality unattainable with ivory's variable sourcing.[33]Manufacturing Process

Production Techniques

Billiard balls are manufactured primarily through casting phenolic resin—a thermosetting polymer derived from phenol and formaldehyde—into spherical molds, followed by controlled curing under heat and pressure to achieve uniform density and hardness essential for predictable collision outcomes.[36] The resin is loaded into preheated molds at temperatures around 163–182°C and subjected to pressures of 30–50 MPa, allowing the material to flow, polymerize, and solidify into dense cores resistant to deformation.[37] [38] This step leverages the resin's thermosetting properties to form a vitrified structure, where cross-linking occurs irreversibly, yielding balls capable of withstanding repeated high-impact forces without cracking or warping.[39] Post-curing, the rough spheres undergo precision machining on computer-controlled lathes to refine diameter and sphericity, followed by tumbling, grinding, and multi-stage polishing to achieve roundness tolerances of ±0.01 mm and surface finishes that minimize friction variations during rolls.[40] These finishing techniques ensure sphericity deviations below thresholds that could otherwise cause erratic paths or spins, directly supporting causal consistency in game physics by aligning ball trajectories with initial velocity and angle inputs.[41] Numbering for pool and snooker variants integrates numerals and spots either via colored resin inserts during molding or post-process laser etching calibrated to preserve balance, limiting center-of-mass offsets to under 0.5 mm for unbiased momentum transfer in collisions.[42] Leading producer Saluc, under the Aramith brand, employs a 13-step protocol spanning up to 23 days per set, encompassing these molding, curing, and refinement stages to dominate over 85% of global output.[40] [41]Quality Assurance

Quality assurance for billiard balls entails rigorous empirical evaluations to verify performance consistency, focusing on metrics such as sphericity, balance, density uniformity, and hardness to ensure predictable dynamics in collisions and rolls.[25] Sphericity is gauged using precision instruments to confirm roundness within tolerances better than Grade III plastic ball standards, preventing deviations that could alter roll paths.[21] Balance checks involve spin and roll tests to detect imbalances causing wobble or uneven deceleration, while density assessments ensure uniform mass distribution for stable rebound and spin control.[43] Hardness testing, targeting values exceeding 73 HRH (Rockwell H scale), confirms resistance to deformation under impact, with premium phenolic resin balls like those from Aramith achieving over 80 HRH for superior durability—withstanding up to 50 times more impacts than alternatives.[21][22] For tournament-grade balls, adherence to standards set by organizations like the World Pool-Billiard Association (WPA) is essential, requiring phenolic resin construction, a diameter of 2.25 inches (±0.005 inches), and weights between 5.5 and 6 ounces (156–170 grams) to maintain uniformity across cue and object balls.[44] WPA-sanctioned events mandate balls meeting these physics-based thresholds for fair play, with manufacturers like Aramith providing quality certificates verifying compliance across seven criteria, including sphericity and balance, to support consistent rebound and trajectory predictability.[25] These evaluations prioritize causal factors like material homogeneity over cosmetic appeal, as variances in hardness or density directly affect energy transfer in collisions, influencing professional outcomes.[45] Counterfeit balls, often originating from unregulated Chinese production, undermine these standards by failing hardness and density tests, resulting in lighter weights, irregular sphericity, and erratic rebounds that compromise game fairness in competitive settings.[46] Genuine manufacturers warn against such imitations, which flood markets and exhibit subpar performance, such as uneven surfaces leading to unpredictable spins—issues exacerbated by lax oversight in import supply chains.[47] This proliferation has prompted calls for stricter verification in pro circuits, as substandard balls can alter collision physics, favoring inconsistent play over skill.[46]Physical Characteristics and Physics

Dimensions, Weight, and Tolerances

Billiard balls exhibit standardized dimensions and weights tailored to specific games, with tolerances enforced to minimize variations in performance on level tables. Professional standards generally require diameters between 52 mm and 61.5 mm and weights from 113 g to 220 g, depending on the variant, ensuring consistent spherical geometry where the moment of inertia follows for ideal solid spheres.[21] In pool, as per World Pool-Billiard Association (WPA) specifications, balls measure 57.15 mm (2.25 inches) in diameter with a tolerance of +0.127 mm, and weigh between 156 g and 170 g.[44] These parameters apply uniformly to cue and object balls, promoting predictable rebound and roll without numerical markings affecting balance. Snooker balls adhere to a diameter of 52.5 mm with a ±0.05 mm tolerance, while weights within a set vary by no more than 3 g to maintain equity.[48] No absolute weight is mandated, but practical sets fall around 120 g on average, with premium manufacturers achieving 1 g tolerance for enhanced precision.[49] Carom billiards uses unnumbered balls of 61 mm to 61.5 mm diameter and 205 g to 220 g weight, per Union Mondiale de Billard (UMB) rules, emphasizing uniformity across the three balls (typically two cue balls and one object ball).[50]| Game Type | Diameter (mm) | Tolerance (mm) | Weight (g) | Weight Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool (WPA) | 57.15 | +0.127 | 156–170 | Uniform set |

| Snooker | 52.5 | ±0.05 | ~120 (avg) | ≤3 g per set |

| Carom (UMB) | 61–61.5 | N/A | 205–220 | Uniform set |