Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boston Marathon

View on Wikipedia

| Boston Marathon | |

|---|---|

Current logo, introduced in June 2024[1] | |

| Date | Usually the third Monday of April (Patriots' Day) |

| Location | Eastern Massachusetts, ending in Boston |

| Event type | Road |

| Distance | Marathon |

| Established | 1897 |

| Course records | Men: 2:03:02 (2011) Geoffrey Mutai Women: 2:17:22 (2025) Sharon Lokedi |

| Official site | www |

The Boston Marathon is an annual marathon race hosted by eight cities and towns in greater Boston in eastern Massachusetts, United States. It is traditionally held on Patriots' Day, the third Monday of April.[2] Begun in 1897, the event was inspired by the success of the first marathon competition in the 1896 Summer Olympics.[3] The Boston Marathon is the world's oldest annual marathon and ranks as one of the world's best-known road racing events. It is one of seven World Marathon Majors. Its course runs from Hopkinton in southern Middlesex County to Copley Square in Boston.

The Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.) has organized this event annually since 1897,[4] including a "virtual alternative" after the 2020 road race was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The race has been managed by DMSE Sports since 1988. Amateur and professional runners from all over the world compete in the Boston Marathon each year, braving the hilly Massachusetts terrain and varying weather to take part in the race.

The event attracts 500,000 spectators along the route, making it New England's most viewed sporting event.[5] Starting with just 15 participants in 1897, the event has grown to an average of about 30,000 registered participants each year, with 30,251 people entering in 2015.[6] The Centennial Boston Marathon in 1996 established a record as the world's largest marathon with 38,708 entrants, 36,748 starters, and 35,868 finishers.[5]

History

[edit]

Men have competed in the event since its inaugural edition in 1897. Women were officially allowed to enter the event starting in 1972, although organizers now recognize 1966 as the first edition officially completed by a woman. Wheelchair divisions were added in 1975 for men and in 1977 for women. The first person to officially race in Boston in a wheelchair was Bob Hall.[7] Handcycle divisions were added in 2017 for both men and women.[citation needed]

The Boston Marathon was first run in April 1897, having been inspired by the revival of the marathon for the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece. Until 2020 it was the second oldest continuously running marathon,[citation needed] and the third longest continuously running footrace in North America, having debuted five months after the five mile Buffalo Turkey Trot[8] race.

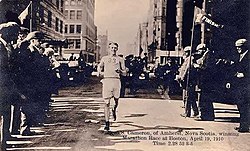

On April 19, 1897, ten years after the establishment of the B.A.A., the association held the 24.5-mile (39.4 km) marathon to conclude its athletic competition, the B.A.A. Games.[4] The winner of the inaugural edition was John J. "JJ" McDermott,[5] who ran the 24.5-mile course in 2:55:10, leading a field of 15. The event was scheduled for the recently established holiday of Patriots' Day, with the race linking the Athenian and American struggles for liberty.[9] The race, which became known as the Boston Marathon, has been held in some form every year since then, even during the World War years and the Great Depression, making it the world's oldest annual marathon. In 1924, the starting line was moved from Metcalf's Mill in Ashland to the neighboring town of Hopkinton. The course was lengthened to 26 miles 385 yards (42.195 km) to conform to the standard set by the 1908 Summer Olympics and codified by the IAAF in 1921.[10] The first 1.9 miles (3.1 km) are run in Hopkinton before the runners enter Ashland.[11]

The Boston Marathon was originally a local event, but its fame and status have attracted runners from all over the world. For most of its history, the Boston Marathon was a free event, and the only prize awarded for winning the race was a wreath woven from olive branches.[12] However, corporate-sponsored cash prizes began to be awarded in the 1980s, when professional athletes refused to run the race unless a cash award was available. The first cash prize for winning the marathon was awarded in 1986.[13]

Walter A. Brown was the President of the Boston Athletic Association from 1941 to 1964.[14] During the height of the Korean War in 1951, Brown denied Koreans entry into the Boston Marathon.[15] He stated: "While American soldiers are fighting and dying in Korea, every Korean should be fighting to protect his country instead of training for marathons. As long as the war continues there, we positively will not accept Korean entries for our race on April 19."[16]

Bobbi Gibb, Kathrine Switzer, and Nina Kuscik

[edit]

The Boston Marathon rule book made no mention of gender until after the 1967 race.[17] Nor did the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) exclude women from races that included men until after the 1967 Boston Marathon.[18] Roberta "Bobbi" Gibb's attempt to register for the 1966 race was refused by race director Will Cloney in a letter in which he claimed women were physiologically incapable of running 26 miles.[19] Gibb nevertheless ran unregistered and finished the 1966 race in three hours, twenty-one minutes and forty seconds,[20] ahead of two-thirds of the runners. Much later, she would be recognized by the race organizers as the first woman to run the entire Boston Marathon.[citation needed]

In 1967, Kathrine Switzer, who registered for the race using her official AAU registration number, paying the entry fee, providing a properly acquired fitness certificate, and signing her entry form with her usual signature 'K. V. Switzer', was the first woman to run and finish with a valid official race registration.[17] As a result of Switzer's completion of the race as the first officially registered woman runner, the AAU changed its rules to ban women from competing in races against men.[18] Switzer finished the race despite race official Jock Semple repeatedly assaulting her in an attempt to rip off her race numbers and eject her from the race.[17][21] Afterwards, Semple and Switzer became friends.[22]

Nina Kuscsik was instrumental in influencing the Amateur Athletic Union, in late 1971, to increase its maximum distance for sanctioned women's races, leading to official participation by women in marathons, beginning at Boston in 1972.[23] Kuscsik was the first woman to officially win the Boston Marathon, which occurred in 1972.[24]

In 1996, the B.A.A. retroactively recognized as champions the unofficial women's leaders of 1966 through 1971. In 2022, about 43 percent of the entrants were women.[25]

Rosie Ruiz, the impostor

[edit]In 1980, Rosie Ruiz crossed the finish line first in the women's race. However, marathon officials became suspicious, and it was discovered that she did not appear in race videotapes until near the end of the race, with a subsequent investigation concluding that she had skipped most of the race and blended into the crowd about a half-mile (800 m) from the finish line, where she then ran to her false victory. She was disqualified eight days later, and Canadian Jacqueline Gareau was proclaimed the winner.[26][27]

Participant deaths

[edit]In 1905, James Edward Brooks of North Adams, Massachusetts, died of pneumonia shortly after running the marathon.[28] In 1996, a 61-year-old Swedish man, Humphrey Siesage, died of a heart attack during the 100th running.[29] In 2002, Cynthia Lucero, 28, died of hyponatremia.[30]

2011: Geoffrey Mutai and the IAAF

[edit]On April 18, 2011, Geoffrey Mutai of Kenya won the 2011 Boston Marathon in a time of 2:03:02:00.[31] Although this was the fastest marathon ever run at the time, the International Association of Athletics Federations noted that the performance was not eligible for world record status given that the course did not satisfy rules that regarded elevation drop and start/finish separation (the latter requirement being intended to prevent advantages gained from a strong tailwind, as was the case in 2011).[32] The Associated Press (AP) reported that Mutai had the support of other runners who describe the IAAF's rules as "flawed".[33] According to the Boston Herald, race director Dave McGillivray said he was sending paperwork to the IAAF in an attempt to have Mutai's mark ratified as a world record.[31] Although this was not successful, the AP indicated that the attempt to have the mark certified as a world record "would force the governing bodies to reject an unprecedented performance on the world's most prestigious marathon course".[33]

2013: Bombing

[edit]On April 15, 2013, the Boston Marathon was still in progress at 2:49 p.m. EDT (nearly three hours after the winner crossed the finish line), when two homemade bombs were set off about 200 yards (180 m) apart on Boylston Street, in approximately the last 225 yards (200 m) of the course. The race was halted, preventing many from finishing.[34][35] Three spectators were killed and an estimated 264 people were injured.[36] Entrants who completed at least half the course and did not finish due to the bombing were given automatic entry in 2014.[37] In 2015, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the perpetrators of the bombing, was found guilty of 30 federal offenses in connection with the attack and was sentenced to death. His older brother Tamerlan died after a gunfight with police and after Dzhokhar ran him over with a stolen vehicle.[38][39]

2014: Women's race disqualification

[edit]Bizunesh Deba of Ethiopia was eventually named women's winner of the 2014 Boston Marathon, following the disqualification of Kenyan Rita Jeptoo from the event due to confirmed doping. Deba finished in a time of 2:19:59, and became the course record holder. Her performance bested that of Margaret Okayo, who ran a time of 2:20:43 in 2002.[40]

2016: Bobbi Gibb as grand marshal

[edit]In the 2016 Boston Marathon, Jami Marseilles, an American, became the first female double amputee to finish the Boston Marathon.[41][42] Bobbi Gibb, the first woman to have run the entire Boston Marathon (1966), was the grand marshal of the race.[43] The Women's Open division winner, Atsede Baysa, gave Gibb her trophy; Gibb said that she would go to Baysa's native Ethiopia in 2017 and return it to her.[44]

2020: Cancellation

[edit]Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 Boston Marathon was initially rescheduled from April 20 to September 14.[45] It was the first postponement in the more than 100 year uninterrupted history of the event.[46]

On May 28, 2020, it was announced that the rescheduled marathon set for September 14 was canceled.[47] Boston Mayor Marty Walsh said of the decision to cancel the race, "There's no way to hold this usual race format without bringing large numbers of people into close proximity. While our goal and our hope was to make progress in containing the virus and recovering our economy, this kind of event would not be responsible or realistic on September 14 or any time this year."[48]

Runners were issued full refunds of entry fees.[49] Organizers later staged a "virtual alternative" in September 2020 as the 124th running of the marathon.[50] This was the second time that the format of the marathon was modified, the first having been in 1918, when the race was changed from a marathon to a military relay race (ekiden) because of World War I.[51]

2021: Rescheduled to October

[edit]On October 28, 2020, the B.A.A. announced that the 2021 edition of the marathon would not be held in April; organizers stated that they hoped to stage the event later in the year, possibly in the autumn.[52] In late January 2021, organizers announced October 11 as the date for the marathon, contingent upon road races being allowed in Massachusetts at that time.[53] In March, organizers announced that the field would be limited to 20,000 runners.[54] The race was the fourth of the five World Marathon Majors held in 2021; all the events in the series were run in the space of six weeks between late September and early November.[55] In 2021, the B.A.A. also offered a virtual alternative to the in-person race to be completed anytime between 8–10 October.[56]

Race

[edit]Qualifying

[edit]| Age | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 18–34 | 2 h 55 min | 3 h 25 min |

| 35–39 | 3 h 00 min | 3 h 30 min |

| 40–44 | 3 h 05 min | 3 h 35 min |

| 45–49 | 3 h 15 min | 3 h 45 min |

| 50–54 | 3 h 20 min | 3 h 50 min |

| 55–59 | 3 h 30 min | 4 h 00 min |

| 60–64 | 3 h 50 min | 4 h 20 min |

| 65–69 | 4 h 05 min | 4 h 35 min |

| 70–74 | 4 h 20 min | 4 h 50 min |

| 75–79 | 4 h 35 min | 5 h 05 min |

| ≥80 | 4 h 50 min | 5 h 20 min |

The Boston Marathon is open to runners 18 or older from any nation, but they must meet certain qualifying standards.[59] To qualify, a runner must first complete a standard marathon course certified by a national governing body affiliated with the World Athletics within a certain period of time before the date of the desired Boston Marathon (usually within approximately 18 months prior).[citation needed]

In the 1980s and 1990s, membership in USA Track & Field was required of all runners, but this requirement has been eliminated.[60]

Qualifying standards for the 2013 race were tightened on February 15, 2011, by five minutes in each age-gender group for marathons run after September 23, 2011.[61] Prospective runners in the age range of 18–34 must run a time of no more than 3:00:00 (3 hours) if male, or 3:30:00 (3 hours 30 minutes) if female; the qualifying time is adjusted upward as age increases. In addition, the 59-second grace period on qualifying times has been eliminated; for example, a 40- to 44-year-old male will no longer qualify with a time of 3:10:01. For many marathoners, to qualify for Boston (to "BQ") is a goal and achievement in itself.[62][63] This leads many runners to find intrinsic motivation in qualifying for the elusive marathon by setting the specific, time-based, and difficult goals associated with the age-based time standard.[64]

An exception to the qualification times is for runners who receive entries from partners. About one-fifth of the marathon's spots are reserved each year for charities, sponsors, vendors, licensees, consultants, municipal officials, local running clubs, and marketers. In 2010, about 5,470 additional runners received entries through partners, including 2,515 charity runners.[65] The marathon currently allocates spots to two dozen charities who in turn are expected to raise more than $10 million a year.[66] In 2017, charity runners raised $34.2 million for more than 200 non-profit organizations. The Boston Athletic Association's Official Charity Program raised $17.96 million, John Hancock's Non-Profit Program raised $12.3 million, and the last $3.97 million was raised by other qualified and invitational runners.[67]

On October 18, 2010, the 20,000 spots reserved for qualifiers were filled in a record-setting eight hours and three minutes.[68] The speed of registration prompted the B.A.A. to change its qualifying standards for the 2013 marathon onward.[61] In addition to lowering qualifying times, the change includes a rolling application process, which gives faster runners priority. Organizers decided not to significantly adjust the number of non-qualifiers.[citation needed]

On September 27, 2018, the B.A.A. announced that they were lowering the qualifying times for the 2020 marathon by another five minutes, with male runners in the 18-34 age group required to run a time of 3:00:00 (3 hours) or less and female runners in the 18-34 age group required to run a time of 3:30:00 (3 hours, 30 minutes) or less in order to qualify.[69]

In September 2024, the B.A.A. announced new qualifying times for the 2026 race, lowering the former qualifying times by five minutes for most age groups. The 18-34 age group needs to run a time of 2:55 (two hours, 55 minutes) for males, and 3:25 (3 hours, 25 minutes) for female and non-binary runners to qualify for the 2026 race.[58][70]

Race day

[edit]The race has traditionally been held on Patriots' Day,[71] a state holiday in Massachusetts. Through 1968, the holiday was observed on April 19, with the event held that day, unless it fell on a Sunday, in which case the race was held on Monday.[72] Since 1969, the holiday has been observed on the third Monday in April,[73] with the event held then, often referred to locally as "Marathon Monday".[74]

Starting times

[edit]Through 2005, the race began at noon (wheelchair race at 11:25 a.m., and elite women at 11:31 a.m.), at the official starting point in Hopkinton, Massachusetts. In 2006, the race used a staggered "wave start", where top-seeded runners (the elite men's group) and a first batch of up to 10,000 runners started at noon, with a second group starting at 12:30. The next year the starting times for the race were moved up, allowing runners to take advantage of cooler temperatures and enabling the roads to be reopened earlier. The marathon later added third and fourth waves to help further stagger the runners and reduce congestion.[75][76][77]

The starting times for 2019 were:[78][79]

- Men's Push Rim Wheelchair: 9:02 a.m.

- Women's Push Rim Wheelchair: 9:04 a.m.

- Handcycles and Duos: 9:25 a.m.

- Elite Women: 9:32 a.m.

- Elite Men: 10 a.m.

- Wave One: 10:02 a.m.

- Wave Two: 10:25 a.m.

- Wave Three: 10:50 a.m.

- Wave Four: 11:15 a.m.

Course

[edit]

The course runs through 26 miles 385 yards (42.195 km) of winding roads, following Route 135, Route 16, Route 30 and city streets into the center of Boston, where the official finish line is located at Copley Square, alongside the Boston Public Library. The race runs through eight Massachusetts cities and towns: Hopkinton, Ashland, Framingham, Natick, Wellesley, Newton, Brookline, and Boston.[80]

The Boston Marathon is considered to be one of the more difficult marathon courses because of the Newton hills, which culminate in Heartbreak Hill near Boston College.[81] While the three hills on Commonwealth Avenue (Route 30) are better known, a preceding hill on Washington Street (Route 16), climbing from the Charles River crossing at 16 miles (26 km), is regarded by Dave McGillivray, the long-term race director, as the course's most difficult challenge.[82][83] This hill, which follows a 150-foot (46 m) rise over a 1⁄2 mile (800 m) stretch, forces many lesser-trained runners to a walking pace.[citation needed]

Heartbreak Hill

[edit]Heartbreak Hill is an ascent over 0.4 miles (600 m) between the 20- and 21-mile (32- and 34-km) marks, near Boston College. It is the last of four "Newton hills", which begin at the 16-mile (26 km) mark and challenge contestants with late (if modest) climbs after the course's general downhill trend to that point. Though Heartbreak Hill itself rises only 88 feet (27 m) vertically (from an elevation of 148 to 236 feet (45 to 72 m)),[84] it comes in the portion of a marathon distance where muscle glycogen stores are most likely to be depleted—a phenomenon referred to by marathoners as "hitting the wall".[citation needed]

It was on this hill that, in 1936, defending champion John A. "Johnny" Kelley overtook Ellison "Tarzan" Brown, giving him a consolatory pat on the shoulder as he passed. This gesture renewed the competitive drive in Brown, who rallied, pulled ahead of Kelley, and went on to win—thereby, it was said, breaking Kelley's heart.[85][86]

Records

[edit]

Because the course drops 459 feet (140 m) from start to finish[33] and the start is quite far west of the finish, allowing a helpful tailwind, the Boston Marathon does not satisfy two of the criteria necessary for the ratification of world[87] or American records.[88]

At the 2011 Boston Marathon on April 18, 2011, Geoffrey Mutai of Kenya ran a time of 2:03:02, which was the fastest ever marathon at the time (since surpassed by Eliud Kipchoge's 2:01:39 in Berlin 2018). However, due to the reasons listed above, Mutai's performance was not ratified as an official world record. Bezunesh Deba from Ethiopia set the women's course record with a 2:19:59 performance on April 21, 2014. This was declared after Rita Jeptoo from Kenya was disqualified following a confirmed doping violation.[89]

Other course records include:

- Men's Masters: John Campbell (New Zealand), 2:11:04 (set in 1990)

- Women's Masters: Firiya Sultanova-Zhdanova (Russia), 2:27:58 (set in 2002)

- Men's Push Rim Wheelchair: Marcel Hug (Switzerland), 1:17:06 (set in 2023)

- Women's Push Rim Wheelchair: Manuela Schär (Switzerland), 1:28:17 (set in 2017)

- Men's Handcycle: Tom Davis (United States), 0:58:36 (set in 2017)

- Women's Handcycle: Alicia Dana (United States), 1:18:15 (set in 2023)[90]

On only four occasions have world record times for marathon running been set in Boston.[citation needed] In 1947, the men's record time set was 2:25:39, by Suh Yun-Bok of South Korea. In 1975, a women's world record of 2:42:24 was set by Liane Winter of West Germany, and in 1983, Joan Benoit Samuelson of the United States ran a women's world record time of 2:22:43. In 2012 Joshua Cassidy of Canada set a men's wheelchair marathon world-record time of 1:18:25.[citation needed]

In 2007, astronaut Sunita Williams was an official entrant of the race, running a marathon distance while on the International Space Station, becoming the first person to run a marathon in space. She was sent a specialty bib and medal by the B.A.A. on the STS-117 flight of the Space Shuttle Atlantis.[91][92]

The race's organizers keep a standard time clock for all entries, though official timekeeping ceases after the six-hour mark.[93]

The B.A.A.

[edit]The Boston Athletic Association is a non-profit, organized sports association that organizes the Boston Marathon and other events.[4][94]

Divisions

[edit]The 1975 Boston Marathon became the first major marathon to include a wheelchair division competition.[5] Bob Hall wrote race director Will Cloney to ask if he could compete in the race in his wheelchair. Cloney wrote back that he could not give Hall a race number, but would recognize Hall as an official finisher if he completed the race in under 3 hours and 30 minutes. Hall finished in 2 hours and 58 minutes, paving the way for the wheelchair division.[95] Ernst Van Dyk, in 2004, set a course record at 1:18.29, almost 50 minutes faster than the fastest runner.[96]

Also in 1975, the Boston Marathon first included a women's masters division, which Sylvia Weiner won, at age 44 with a time of 3:21:38.[97]

Handcyclists have competed in the race since at least 2014. Starting in 2017, handcyclists are honored the same way runners and wheelchair racers are: with wreaths, prize money, and the playing of the men's and women's winners' national anthems.[98]

In addition to the push rim wheelchair division, the Boston Marathon[99] also hosts a blind/visually impaired division, and a mobility impaired program. Similar to the running divisions, a set of qualifying times has been developed for these divisions to motivate aspiring athletes and ensure competitive excellence. In 1986, the introduction of prize money at the Boston Marathon gave the push rim wheelchair division the richest prize purse in the sport. More than 1,000 people with disabilities and impairments have participated in the wheelchair division, while the other divisions have gained popularity each year.[100] In 2013, 40 blind runners participated.[101]

The nonbinary division of the Boston Marathon was first included in 2023; it was won by Kae Ravichandran with a time of 2:38:57.[102]

Memorial

[edit]The Boston Marathon Memorial in Copley Square, which is near the finish line, was installed to mark the one-hundredth running of the race. A circle of granite blocks set in the ground surrounds a central medallion that traces the race course and other segments that show an elevation map of the course and the names of the winners.[103][104]

Notable features

[edit]Spectators

[edit]With approximately 500,000 spectators, the Boston Marathon is New England's most widely viewed sporting event.[5] About 1,000 media members from more than 100 outlets received media credentials in 2011.[105]

For the entire distance of the race, thousands line the sides of the course to cheer the runners on, encourage them, and provide free water and snacks to the runners.[citation needed]

Scream Tunnel

[edit]

At Wellesley College, a historically women's college, it is traditional for the students to cheer on the runners in what is referred to as the Scream Tunnel.[106][107] For about a quarter of a mile (400 m), the students line the course, scream, and offer kisses. The Scream Tunnel is so loud runners claim it can be heard from a mile away. The tunnel is roughly half a mile (0.8 km) prior to the halfway mark of the course.[108][109]

Boston Red Sox

[edit]Every year, the Boston Red Sox play a home game at Fenway Park, starting at 11:05 a.m. When the game ends, the crowd empties into Kenmore Square to cheer as the runners enter the final mile. This tradition started in 1903.[110] In the 1940s, the Red Sox from the American League and the Boston Braves from the National League (who moved to Milwaukee after the 1953 season) alternated yearly as to which would play the morning game. In 2007, the game between the Red Sox and the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim was delayed until 12:18 p.m. due to heavy rain. The marathon, which had previously been run in a wide variety of weather conditions, was not delayed.[111] The 2018 game hosting the Baltimore Orioles was postponed into May due to rain,[112] while 2020 saw the game not played resulting from the pandemic.

In 2021, when City Connect uniforms were introduced, the Red Sox chose a design inspired by the marathon. The colors were yellow and blue, and a number "617" - the area code for Boston - was added to the left sleeve in a way reminiscent of a racing bib. They were worn on the weekend leading up to Patriots' Day; on the holiday itself, the Boston Strong uniforms commemorating the 2013 bombing were worn.[113] A new City Connect uniform was chosen in 2025, with the marathon-themed one remaining as an alternate.[114]

Dick and Rick Hoyt

[edit]

Dick and Rick Hoyt entered the Boston Marathon 32 times.[115] Dick was the father of Rick, who had cerebral palsy. While doctors said that Rick would never have a normal life and thought that institutionalizing him was the best option, Dick and his wife disagreed and raised him at home. Eventually, a computer device was developed that helped Rick communicate with his family, and they learned that one of his biggest passions was sports. "Team Hoyt" (Dick and Rick) started competing in charity runs, with Dick pushing Rick in a wheelchair. Through August 2008, Dick and Rick had competed in 66 marathons and 229 triathlons. Their fastest marathon finish was 2:40:47.[citation needed] The team completed their 30th Boston Marathon in 2012, when Dick was 72 and Rick was 50.[116] They had intended the 2013 marathon to be their final one, but due to the Boston Marathon bombing, they were stopped a mile short of completing their run, and decided to run one more marathon the following year. They completed the 2014 marathon on April 21, 2014, having previously announced that it would be their last.[117] In tribute to his connection with the race, Dick was named the Grand Marshal of the 2015 marathon. He died in 2021, aged 80.[118] Rick died in May 2023.[119]

Bandits

[edit]Unlike many other races, the Boston Marathon tolerated "bandits" (runners who do not register and obtain a bib number).[120] They used to be held back until after all the registered runners had left the starting line, and then were released in an unofficial fourth wave. They were generally not pulled off the course and mostly allowed to cross the finish line.[120] For decades, these unofficial runners were treated like local folk heroes, celebrated for their endurance and spunk for entering a contest with the world's most accomplished athletes.[121] Boston Marathon race director Dave McGillivray was once a teenage bandit.[122]

Given the increased field that was expected for the 2014 Marathon, however, organizers planned "more than ever" to discourage bandits from running.[123] As of September 2015 the B.A.A. website states:

Q: Can I run in the Boston Marathon as an unofficial or "bandit" runner? A: No, please do NOT run if you have not been officially entered in the race. Race amenities along the course and at the finish, such as fluids, medical care, and traffic safety, are provided based on the number of expected official entrants. Any addition to this by way of unofficial participants, adversely affects our ability to ensure a safe race for everyone.[124]

Costumes

[edit]A number of people choose to run the course in a variety of costumes each year.[125][126] During the 100th running in 1996, one runner wore a scale model of the Old North Church steeple on his back. Old North Church is where the signal was lit that set Paul Revere off on his midnight ride, which is commemorated each year on the same day as the Marathon. During the 2014 marathon, runners and spectators were discouraged from wearing "costumes covering the face or any non-form fitting, bulky outfits extending beyond the perimeter of the body," for security reasons following the 2013 bombing. However, state authorities and the Boston Athletic Association did not outright ban such costumes.[127]

Ondekoza taiko drummers

[edit]

Starting in 1975, members of Ondekoza, a group from Japan, would run the marathon and right after finishing the race would start playing their taiko drums at the finish line.[128][129][130][131] They repeated the tradition several times in the 1970s and 1990s.[132][133][134][135] The 700-pound (320 kg) drum would be set up at the finish line to encourage runners finishing the marathon. Bill Rodgers, who inspired member's running, was a guest on Sado Island and ran marathons in Japan with Ondekoza members.[136] The group also ran the New York City Marathon and Los Angeles Marathon, and ran 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of the perimeter of the United States from 1990 to 1993.[137][138]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Launch of new Boston Marathon logo on Global Running Day symbolizes moving forward together". baa.org (Press release). Boston Athletic Association. June 5, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2025.

- ^ "Marathon Dates". BAA.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ "The First Boston Marathon". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c "About Us". BAA.org. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Boston Marathon History: Boston Marathon Facts". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Boston Marathon Race Statistics, 2015". Race Statistics, 2015. Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ^ "Against the Wind: Racing the Wind 2". July 27, 2011. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2025.

- ^ Graham, Tim (November 24, 2011). "Pollow takes third consecutive Turkey Trot amid the goofballs". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on November 26, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ "The History of the Boston Marathon: A Perfect Way to Celebrate Patriot's Day". The Atlantic. April 17, 2013. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Timeline of Events". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "'There's a big buzz' as Hopkinton sets up for upcoming Boston Marathon". WCVB. April 12, 2023. Archived from the original on April 16, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ "Q&A: The Boston Marathon". Wasabi Media Group. April 20, 2010. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ "De Castella and Kristiansen Win First Cash Prize". NY Times Co. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ Pave, Marvin (April 17, 2008). "Legacy on the line". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Koreans and the Boston Marathon | Center for Global Christianity & Mission". www.bu.edu. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Sport: Banned in Boston". Time. February 12, 1951. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c

Switzer, Kathrine (April 4, 2017). Marathon Woman (4th ed.). Da Capo Press Inc. ISBN 978-0306825651. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

We checked the rule book and entry form; there was nothing about gender in the marathon. I filled in my AAU number, plunked down $3 cash as entry fee, signed as I always sign my name, 'K.V. Switzer,' and went to the university infirmary to get a fitness certificate.

- ^ a b

Romanelli, Elaine (1979). "Women in Sports and Games". In O'Neill, Lois Decker (ed.). The Women's Book of World Records and Achievements. Anchor Press. p. 576. ISBN 0-385-12733-2.

[Switzer's] run created such a stir that the AAU [...] barred women from all competition with men in these events on pain of losing all rights to compete.

- ^ Gibbs, Roberta "Bobbi". "Roberta "Bobbi" Gibb - A Run of One's Own". Women's Sports Foundation. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ Derderian, Tom (1996). Boston Marathon: The History of the World's Premier Running Event. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics Publishers.

- ^ "NPR: Marathon Women". NPR. April 15, 2002. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Who Was That Guy Who Attacked Kathrine Switzer 50 Years Ago?". Runner's World. April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2025.

- ^ Butler, Charles (October 19, 2012). "40 Years Ago, Six Women Changed Racing Forever". Runner's World. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ "Nina Kuscsik". Distance Running. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Tumin, Remy (April 18, 2022). "In 1972, only 8 women ran the race. Today, 12,100 are running". New York Times. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Boston Athletic Association (2011). "Boston Marathon History: 1976–1980". baa.org. Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Boston disqualifies Rosie Ruiz". Boca Raton News. April 30, 1980. p. 3C. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Johanne Grewell. "Eleanor Brooks Fairs." American Communal Societies Quarterly, October 2009.

- ^ "Heartbreak Hill Claims Another Victim". Associated Press News. April 16, 1996. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ^ "Fluid Cited in Marathoner's Death". Associated Press News. August 13, 2002. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Connolly, John (April 20, 2011). "BAA on record: Geoffrey Mutai's No. 1". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Monti, David (April 18, 2011). "Strong winds and ideal conditions propel Mutai to fastest Marathon ever - Boston Marathon report". iaaf.org. International Association of Athletics Federations. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c Golen, Jimmy (April 19, 2011). "Boston wants Mutai's 2:03:02 to be world record". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Explosions rock Boston Marathon, several injured". CNN. April 15, 2013. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Golen, Jimmy (April 15, 2013). "Two explosions at Boston marathon finish line". AP Newswire. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Kotz, Deborah (April 24, 2013). "Injury toll from Marathon bombs reduced to 264". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

Boston public health officials said Tuesday that they have revised downward their estimate of the number of people injured in the Marathon attacks, to 264.

- ^ Stableford, Dylan (May 16, 2013). "Runners who didn't finish Boston Marathon due to bombings to get automatic entry in 2014". The Lookout. Archived from the original on June 10, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "In Watertown, one brother's decision led to death of another". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ "What Happened To Dzhokhar Tsarnaev? Update On Boston Marathon Bomber Sentenced To Death". International Business Times. April 16, 2017. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Boston Athletic Association. "Buzunesh Deba Named 2014 Boston Marathon Champion". B.A.A. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ Bruce Gellerman (April 19, 2016). "Bilateral Amputee Jami Marseilles Makes Boston Marathon History". wbur. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ "Bilateral Amputee Jami Marseilles Completes the Chicago Marathon". Runner's World. October 14, 2015. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ "Bobbi Gibb serves as grand marshal of 2016 Boston Marathon". Wicked Local Rockport. Associated Press.

- ^ "Atsede Baysa gives her Boston Marathon trophy to Bobbi Gibb". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Logan, Tim (March 13, 2020). "Boston Marathon postponed to September due to coronavirus". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ Yang, Nicole (March 13, 2020). "2020 Boston Marathon postponed to Monday, Sept. 14". Boston.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ Waller, John (May 28, 2020). "The 2020 Boston Marathon has been canceled". Boston.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Golen, Jimmy (May 28, 2020). "Boston Marathon canceled for 1st time in 124-year history". The Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ "124th Boston Marathon to be Held Virtually". BAA.org (Press release). Boston Athletic Association. May 28, 2020. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "124th Boston Marathon Virtual Experience Features More Than 15,900 Finishers". BAA.org (Press release). Boston Athletic Association. September 25, 2020. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Golen, Jimmy (March 15, 2018). "Boston Marathon relay to commemorate World War I race". Concord Monitor. Concord, New Hampshire. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ McInerney, Katie (October 28, 2020). "Boston Marathon will not be held in April 2021, BAA announces". Boston.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Sobey, Rick (January 26, 2021). "Boston Marathon set for Oct. 11 — if road races are allowed in Massachusetts coronavirus reopening plan". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Cain, Jonathan (March 15, 2021). "This Year's Boston Marathon, Rescheduled For October, Will Be Capped At 20,000 Runners". WBUR-FM. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ "A look at the tightly packed fall marathon schedule". Running Magazine. January 31, 2021. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Virtual 125th Boston Marathon Fact Sheet | Boston Athletic Association". www.baa.org. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "Qualify | Boston Athletic Association". www.baa.org. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Boston Marathon lowers qualifying times for most prospective runners for 2026 race". AP News. September 17, 2024. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "Participant Information: Qualifying". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Hanc, Jon (January 29, 1999). "Marathoner Hits Bottom Of the World". Newsday.

- ^ a b "New Qualifying Times in Effect for 2013 Boston Marathon". Boston Athletic Association. February 16, 2011. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Burfoot, Amby (April 6, 2009). "All in the Timing". Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Mannes, George (March 29, 2011). "B.Q. or Die". Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Victoria Stewart, Sara S McMillan, Jie Hu, Jack C Collins, Sarira El-Den, Claire L O’Reilly, Amanda J Wheeler, Are SMART goals fit-for-purpose? Goal planning with mental health service-users in Australian community pharmacies, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 36, Issue 1, 2024, mzae009, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzae009

- ^ Hohler, Bob; Springer, Shira (February 17, 2011). "Marathon qualifying is revised". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Boston Marathon Official Charity Program". BAA. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "2017 Boston Marathon Charity Runners Raised $34.2 Million". Competitor.com. June 29, 2017. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ Shira Springer (October 19, 2010). "Online, sprinters win race: Marathon fills its field in a record 8 hours". NY Times Co. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "2019 Boston Marathon Qualifier Acceptances" Archived October 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, BAA.org 2018-09-27, Retrieved 2018-10-26

- ^ Touri, Amin (September 16, 2024). "The Boston Marathon's qualifying standards just got harder. Here's what you need to know". The Boston Globe. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "The Boston Marathon Is Held on Patriots' Day, Which Has Become an Unofficial Anti-Government Day of Action". Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Bird, Hayden (April 15, 2017). "The Boston Marathon wasn't always held on a Monday". Boston.com. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Patriot's Day in United States". Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Hansen, Amy (April 15, 2013). "Potter Twp. native recalls Marathon Monday". Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Boston Marathon Set to Begin Two Hours Earlier". VisitingNewEngland.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Time lapse video of 2008 marathon start". The Boston Globe. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "New Start Structure for the 2011 Boston Marathon". March 7, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Race Day Schedule". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ "What time does the Boston Marathon start?". Boston.com. March 18, 2019. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Event Information: Spectator Information". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Bakken, Marius. "Boston Marathon: Pros and Cons". Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ Connelly, Michael (1998). 26 Miles to Boston. Parnassus Imprints. pp. 105–06. ISBN 9780940160781.

- ^ "Boston Course Tips". Rodale Inc. March 14, 2007. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Boston Marathon Official Program, April 2005, p.68

- ^ Michael Vega (October 7, 2004). "At Heartbreak Hill, a salute to a marathoner for the ages". Boston.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Recalling The Most Memorable Boston Moments". Competitor Group, Inc. April 13, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Malone, Scott; Krasny, Ros (April 18, 2011). "Mutai runs fastest marathon ever at Boston". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 21, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ "USATF Rule 265(5)" (PDF). USATF. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Boston Marathon History: Course Records". Boston Athletic Association website. Archived from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ Doyle, Peyton (April 17, 2023). "Zachary Stinson and Alicia Dana take Boston Marathon handcycle titles: Dana set a course record for women's handcycling". Boston.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ Jimmy Golen for The Associated Press (2007). "Astronaut to run Boston Marathon — in space". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ NASA (2007). "NASA Astronaut to Run Boston Marathon in Space". NASA. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Lorge Butler, Sarah (May 8, 2024). "Controversy Arises Over Boston's Moving 6-Hour Results Cutoff". Runner's World. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Hanc, John (2012). The B.A.A. at 125: The Official History of the Boston Athletic Association, 1887-2012. Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1613211984.

- ^ Savicki, Mike. "Wheelchair Racing in the Boston Marathon". Disaboom. Retrieved April 16, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Fastest Man at the Boston Marathon". Popular Mechanics. April 16, 2010. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ "84-Year-Old Holocaust Survivor Says Running Saved Her Life". Runner's World. April 13, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "BAA to honor handcycle winners, expand field". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ "Marine veteran who crawled to the Boston Marathon finish line was inspired by fallen comrades". Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "Paving the way for disabled athletes since 1975". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Running blind: 40 sightless runners competing in Boston marathon". Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Kae Ravichandran Wins Nonbinary Division at the 2023 Boston Marathon". Runner's World. April 18, 2023.

- ^ "Boston Marathon Memorial". Boston Art Commission. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "100 Public Artworks" (PDF). Boston Marathon Memorial. Boston Art Commission. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Driven to Repeat". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ Pave, Marvin (April 22, 2003). "Resounding Wellesley message: voices carry". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ "Runner's World Slideshow: 2008 Boston Marathon". Runnersworld.com. 2008. Archived from the original on April 23, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ "Marathon Monday". Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Support, kisses at marathon's Scream Tunnel". The Boston Globe. April 16, 2012. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Move Over Marathon: Red Sox Share the Tradition of Patriots' Day". Archived from the original on April 17, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Patriots' Day Weather". April 20, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Red Sox announce postponement of Monday's game". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Red Sox unveil Patriots' Day-inspired unis". MLB.com. Retrieved September 15, 2025.

- ^ "Green Monster the headliner of Red Sox City Connect unis". MLB.com. Retrieved September 15, 2025.

- ^ Bousquet, Josh (April 15, 2012). "Dick and Rick Hoyt are Boston Marathon fixtures". Telegram & Gazette. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ "Dick And Rick Hoyt Complete 30th Boston Marathon". April 16, 2012. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Team Hoyt – father and son Dick and Rick Hoyt – finish final Boston Marathon". MassLive.com. AP. April 21, 2014. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Butler, Sarah Lorge (March 17, 2021). "Dick Hoyt, Part of Legendary Boston Marathon Duo, Dies at 80". Runner's World. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Andersen, Travis (May 22, 2023). "Boston Marathon Legend Rick Hoyt Dies at 61". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 4, 2023. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Helliker, Kevin. "Fleet of Foot and Blissfully Bold, Freeloaders at the Marathon Wear Fake Bibs—but Win No Prizes". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Marathon bandits will be missed this year" Archived May 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Running Last, But Not Least" Archived December 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine,The Boston Globe.

- ^ McGoldrick, Hannah. "Q&A with B.A.A. Executive Director and Boston Marathon Race Director". Runners World. Archived from the original on October 28, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Boston Athletic Association. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ "Costumed runners". Boston.com. April 17, 2011. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Boston Marathon 2013 costumed runners". Boston.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Fans Can Expect Some Changes at Boston Marathon" Archived December 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Runner's World.

- ^ Hughes, Alan (April 30, 1978). "The Fierce Dedication of The 'Demon' Drummers". New York Times. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Ray (April 19, 1975). "These Japanese run with rhythm". Boston Globe.

- ^ Wald, Elijah (December 12, 1994). "Ondekoza, Not Your Humdrum Drummers". Boston Globe.

- ^ Gilbert, Andrew (March 13, 2011). "Drumming up drama". Boston.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Robert (May 11, 1976). "Drum-beating, flute-playing marathoners in lively show". Boston Globe.

- ^ Concannon, Joe (April 17, 1977). "Just a little warm-up:360-mile relay race". Boston Globe.

- ^ "Calendar". Boston Globe. April 10, 1980.

- ^ "Calendar Choice". Boston Globe. April 23, 1987.

- ^ Wald, Elijah (January 10, 1993). "Ondekoza: Japan's Demon Drummers". Boston Globe.

- ^ Longman, Jere (November 10, 1993). "NEW YORK CITY MARATHON; After 9,319-Mile Run, 26.2 Should Be a Mere Stroll". New York Times. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Gaffney, Jim (November 4, 1990). "New York Marathon Sets a First". Modesto Bee.

Further reading

[edit]- History of the Boston Marathon, Boston Marathon: The First Century of the World's Premier Running Event, by Tom Derderian, Human Kinetics Publishers, 1996, 634 pages, ISBN 0-88011-479-7

- Boston Marathon, updated third edition, by Tom Derderian 2017, 827 pages. ISBN 978-1-5107-2428-0, EBook, 978-1-5107-2429-7

External links

[edit]General reference

[edit]- Official website

- History of the Boston Marathon[permanent dead link]

- "Boston Marathon". MarathonGuide.com.

- Boston Marathon: What to Expect on Race Day

- Boston Marathon Course Pace Band

- Weather history

- Course map and elevation

- Course elevation

- The 1918 Boston Marathon Military Relay

Photo and video stories

[edit]Boston Marathon

View on GrokipediaThe Boston Marathon is an annual road running event of 26.219 statute miles (42.195 km), held on Patriots' Day, the third Monday in April, starting in Hopkinton and finishing on Boylston Street in Boston, Massachusetts.[1] Organized by the Boston Athletic Association, it was first run in 1897 as an emulation of the revived Olympic marathon, making it the world's oldest annual marathon.[2][3] The course features a net elevation drop but includes challenging ascents such as the Newton Hills, culminating in the infamous Heartbreak Hill.[4] Entry is primarily by qualifying time standards set by the Boston Athletic Association, which vary by age and gender, ensuring a competitive field of elite and recreational runners; it also holds World Marathon Major status, attracting top international talent and offering substantial prize money.[5] The event has pioneered inclusivity milestones, including the first wheelchair division in 1975 and official admission of women in 1972, though Kathrine Switzer entered as the first officially numbered female participant in 1967, defying organizers' physical efforts to eject her.[6][7] On April 15, 2013, two pressure cooker bombs detonated near the finish line by brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, radicalized Islamists of Chechen origin, killed three spectators and injured over 260, marking a significant terrorist attack on the race.[8][9] Despite such incidents, the marathon endures as a symbol of endurance, drawing over 30,000 participants annually and fostering charitable causes through team efforts like Team Hoyt, where father Dick Hoyt pushed his disabled son Rick in races for decades.[2]

History

Founding and Early Races (1897–1960s)

The Boston Marathon was established by the Boston Athletic Association (BAA), inspired by the marathon event at the revived 1896 Olympic Games in Athens.[10] The inaugural race occurred on April 19, 1897—Patriots' Day in Massachusetts—from Metcalf's Mill in Ashland to the Irvington Oval in Boston, covering 24.5 miles (39.4 km).[11] [10] Fifteen men started the event, with ten finishing; John J. McDermott of New York won in 2:55:10, setting the initial course record.[10] [11] The race was limited to amateur athletes, reflecting the era's emphasis on non-professional competition under BAA rules.[10] Held annually on Patriots' Day, the early marathons attracted modest fields, primarily local and regional runners.[12] Participation grew slowly: 18 entrants in 1897, 24 in 1898, reaching 285 by 1928 before stabilizing around 200 in the late 1950s and early 1960s (198 in 1959, 197 in 1960).[12] Notable early victors included Clarence DeMar, who secured seven titles starting in 1911, the most by any runner in the event's history.[10] In 1918, amid World War I constraints, the full marathon was canceled and replaced by a military relay race won by a team from Camp Devens in 2:24:53.[10] Course adjustments marked key developments: in 1924, the start shifted to Hopkinton Green to extend the distance to the Olympic standard of 26 miles, 385 yards, while maintaining the finish near Copley Square.[10] The 1930s introduced the term "Heartbreak Hill" for a challenging Newton Hills section, coined by journalist Jerry Nason after defending champion Leslie Pawson's collapse there in 1936.[10] Post-World War II, international competition intensified; Korean runner Yun Bok Suh established a world-best time of 2:25:39 in 1947.[10] American dominance waned, with John J. Kelley of the BAA claiming the 1957 victory—the sole U.S. win between 1946 and 1967.[10] Through the 1960s, the race retained its amateur ethos and male-only official participation, with fields hovering near 200 amid growing but limited interest.[12]Expansion of Participation and Rule Changes (1970s–1990s)

In response to the running boom of the 1960s, which increased entrants from 197 in 1960 to 1,342 in 1969, the Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.) introduced qualifying standards in 1970 requiring a sub-4:00 marathon finish to limit the field to approximately 1,000 runners and prevent course congestion.[13] The standard tightened to 3:30 in 1971, reducing the field to 1,067.[13] Women were officially permitted to enter starting in 1972, following unofficial participations such as Kathrine Switzer's bibbed finish in 1967 and Sara Mae Berman's wins in 1969–1971; that year, eight women competed, with Nina Kuscsik winning in 3:10:26.[10] Qualifying for women was set at 3:30, aligning with the men's open standard through 1976.[13] The wheelchair division debuted in 1975, with Bob Hall becoming the first official finisher in 2:58, recognized by the B.A.A. despite starting ahead of able-bodied runners.[10] As participation surged amid the broader jogging trend, the B.A.A. introduced age-graded qualifying times in 1977: 3:00 for men aged 19–39 and 3:05 for women, with 3:30 for men 40 and over, reflecting a doubling of female entrants from 78 in 1976 to 141 in 1977.[13] Standards tightened further in 1980 to 2:50 for open men and 3:20 for women as entrants reached 7,927 in 1979, aiming to manage growth.[13] Additional age divisions were added progressively: 50–59 in 1981–1983 (men 3:20, women 3:40), women's 50–59 in 1984–1986 (3:40), expanding to accommodate rising numbers of older and female runners.[13] John Hancock's sponsorship from 1987 enabled larger fields of about 10,000, prompting relaxed standards such as 3:00 for men 18–39 and 3:30 for women through 1989.[13] By 1990, detailed age-group times were set, including 3:10 for men 18–34 and 3:40 for women in the same bracket, with Jean Driscoll securing the first of seven straight wheelchair women's wins.[10][13] Entrants grew to 9,412 by 1990, reflecting sustained expansion driven by improved accessibility, media coverage, and inclusive divisions.[12]Modern Era and Disruptions (2000s–Present)

The Boston Marathon entered the 21st century with continued dominance by East African runners, particularly Kenyans, in the elite divisions. Catherine Ndereba won the women's open race four times between 2000 and 2005, while Robert Kipkoech Cheruiyot secured three men's victories from 2003 to 2006, including a course record of 2:07:50 in 2006.[10] Geoffrey Mutai's 2011 men's winning time of 2:03:02 marked the fastest marathon performance ever recorded at that point, though ineligible as an official world record due to the course's point-to-point configuration and net downhill profile.[10] Participation expanded significantly, with the field capped at 20,000 entrants in 2003 to manage logistics, but growing to over 30,000 by the 2020s amid heightened global interest.[10] The most profound disruption occurred on April 15, 2013, during the 117th edition, when two brothers of Chechen descent, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev—self-radicalized adherents of jihadist ideology inspired by al-Qaeda publications—detonated homemade pressure cooker bombs hidden in backpacks near the finish line on Boylston Street.[8] The explosions killed three spectators (Krystle Campbell, Lu Lingzi, and Martin Richard) and severely injured more than 260 others, with 17 losing limbs; a fourth victim, MIT police officer Sean Collier, died days later during the ensuing manhunt.[8] Tamerlan was killed in a shootout with police, while Dzhokhar was captured and later convicted on 30 federal charges, including use of a weapon of mass destruction, receiving a death sentence upheld on appeal.[8] The attack prompted "Boston Strong" as a symbol of resilience, with the 2014 race featuring American Meb Keflezighi as the first U.S. male winner since 1983.[10] In response, security protocols were overhauled, including bans on spectators carrying bags larger than 9x12 inches along the route, deployment of thousands of additional law enforcement personnel, and enhanced surveillance with fixed cameras and unmanned aerial systems.[14] Federal agencies like the FBI and DHS increased coordination, providing explosive ordnance disposal teams and intelligence support for subsequent races.[15] The COVID-19 pandemic caused further interruptions: the 2020 race, originally set for April 20, was canceled outright—the first postponement since World War II—and replaced by a virtual event from September 5–14, where 16,183 participants logged distances remotely.[16] The 2021 edition shifted to October 11, limiting in-person participation to elites and select groups under strict health protocols (vaccination proof and masking), with over 22,000 completing virtually; it introduced formal Para Athletics divisions.[10] By 2022, the event returned to its traditional Patriots' Day slot in April, with Evans Chebet of Kenya winning the men's race in a repeat performance.[10] Recent editions, including 2025's victory by John Korir, have seen record charity fundraising exceeding $50 million, underscoring sustained popularity despite past adversities.[10]Race Organization and Entry

Boston Athletic Association Governance

The Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.), a non-profit organization founded on March 15, 1887, is governed by its Board of Governors, which provides strategic oversight to advance the organization's mission of promoting healthy lifestyles through sports, particularly running.[17] [18] As a 501(c)(3) entity dedicated to athletic and charitable purposes, the B.A.A. relies on this volunteer board for high-level decision-making, including approvals for new partners, programs, events, and enterprises.[18] [19] The Board of Governors comprises 14 members, including two Governors Emeriti, selected from a diverse group of experienced Boston-based professionals who serve without compensation.[19] Current leadership includes Chair Cheri Blauwet, MD, who assumed the role in November 2023; Vice Chairs A. Keith McDermott and William F. McCarron (also Treasurer); and Clerk William F. Lee.[19] [20] Other members include Adrienne R. Benton, Peter R. Brown, Jeffrey R. Cameron, William B. Evans, Joann E. Flaminio, Guy L. Morse III, and Michael P. O’Leary, MD.[19] The board's composition emphasizes local expertise in fields such as medicine, law, and business, ensuring alignment with the B.A.A.'s community-focused objectives.[19] Operational leadership falls under President and Chief Executive Officer Jack Fleming, appointed on November 30, 2022, who manages daily activities, staff, and event execution while reporting to the board.[21] This structure separates strategic governance from tactical management, with the board focusing on long-term sustainability and mission adherence, as evidenced by its role in guiding responses to challenges like event disruptions and expansions.[19] The B.A.A. maintains transparency through public disclosure of its tax-exempt status and leadership, though detailed bylaws are not publicly available on its site.[18]Qualifying Standards and Selection Process

The Boston Marathon requires most participants to meet age- and gender-specific qualifying times achieved in certified marathon races to ensure a competitive field.[13] Qualifying times are set by the Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.) and apply to men, women, and non-binary athletes, with non-binary standards aligned to women's times.[13] For the 2026 race, standards were tightened across most age groups by approximately five minutes compared to prior years to manage field size amid growing applicant numbers.[22]| Age Group | Men's Standard | Women's/Non-Binary Standard |

|---|---|---|

| 18–34 | 2:55:00 | 3:25:00 |

| 35–39 | 3:00:00 | 3:30:00 |

| 40–44 | 3:05:00 | 3:35:00 |

| 45–49 | 3:15:00 | 3:45:00 |

| 50–54 | 3:20:00 | 3:50:00 |

| 55–59 | 3:30:00 | 4:00:00 |

| 60–64 | 3:50:00 | 4:20:00 |

| 65–69 | 4:05:00 | 4:35:00 |

| 70–74 | 4:20:00 | 4:50:00 |

| 75–79 | 4:35:00 | 5:05:00 |

| 80+ | 4:50:00 | 5:20:00 |

Course and Competition Format

Route and Terrain Challenges

The Boston Marathon follows a point-to-point course of 26 miles, 385 yards (42.195 km) from Main Street in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, to Copley Square in Boston, traversing suburban and urban terrain along state routes including Massachusetts Route 135 and 16.[23] The route begins at an elevation of approximately 490 feet (149 m) above sea level and ends at 10 feet (3 m), yielding a net descent of 480 feet (146 m), though the path includes 815 feet (248 m) of cumulative uphill climbing that offsets much of the advantage.[24][25] This undulating profile, certified by World Athletics standards, demands strategic pacing to counter the deceptive early declines and late ascents.[26] The first 16 miles feature mostly downhill and rolling sections through Ashland, Framingham, Natick, and Wellesley, with gradients averaging -1% to -0.5%, enabling faster splits but risking quadriceps strain and premature lactic acid buildup from braking on the descent.[27] Runners encounter minor undulations, such as short rises in Natick around mile 10, but the predominant drop lulls participants into aggressive early pacing, often leading to bonking later as glycogen depletes.[28] Pavement consists of standard asphalt roads, exposed to variable April weather including headwinds along straightaways and potential headwinds funneling through urban corridors, exacerbating perceived effort on slight inclines.[29] The defining terrain obstacle arises in the Newton Hills from miles 16 to 21, a series of four climbs totaling over 200 feet (61 m) of ascent after the relative ease of the first half.[30] The initial Newton ascent, crossing Interstate 90 around mile 16.5, presents the steepest grade at 4.4% over 0.3 miles (0.48 km), followed by three progressively longer but shallower rises.[31] Culminating in Heartbreak Hill between miles 20 and 21—a 0.6-mile (0.97 km) climb gaining 89 feet (27 m) at an average 4.5% gradient—this final hill strikes when fatigue peaks, with diminished glycogen stores and accumulated downhill damage amplifying the physiological toll, often causing the largest slowdowns in elite and recreational fields alike.[32][33] Despite modest gradients compared to mountainous marathons, the timing after 20 miles of prior exertion renders it a critical test of endurance, where mental resilience and hill-specific training prove decisive.[34] Post-Newton, the course flattens into Brookline and Boston's urban core, with minor rollers along Commonwealth Avenue and a final slight incline to the finish, but residual hill fatigue and urban crowding compound recovery challenges on the pavement.[35] Overall, the terrain's causal demands—early eccentric loading from descents followed by concentric work on late hills—elevate injury risk, particularly to knees and calves, underscoring the need for downhill simulation in preparation to mitigate eccentric overload.[27]Divisions and Starting Procedures

The Boston Marathon organizes participants into distinct divisions based on ability, impairment, and professional status. The professional open divisions include separate fields for men and women, featuring elite athletes invited by the Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.) based on recent performances and potential to contend for top positions. Professional wheelchair divisions similarly separate men and women, with athletes using racing wheelchairs. Para athletics divisions encompass athletes with various impairments, classified by International Paralympic Committee standards such as T11-T13 for visual impairments and T61-T64 for other categories. Handcycle and duo teams form additional adaptive categories. The open division comprises qualified amateur runners who meet age- and sex-specific time standards, with internal age-group categories (masters for those 40 and older) for awards but not separate starts. A nonbinary category was added to the open division for scoring purposes starting in 2023.[36][37] Starting procedures prioritize safety and pacing by sequencing divisions from specialized to mass participation. Wheelchair athletes initiate the race, with men's wheelchair division starting at 9:06 a.m. ET and women's at 9:09 a.m. ET, allowing time advantages due to the course's downhill profile and speed differences. Handcycle and duo participants follow at 9:30 a.m., then professional men at 9:37 a.m., professional women at 9:47 a.m., and para athletics at 9:50 a.m.[38][39] The open division employs a wave start system to manage the large field of over 30,000 runners, assigning participants to one of four waves based on qualifying times, with faster qualifiers in earlier waves. Each wave contains up to nine corrals, subdivided by bib numbers ordered sequentially by qualifying performance, ensuring similar paces within groups to minimize congestion. Wave 1 begins at 10:00 a.m. ET, followed by Wave 2 at 10:25 a.m., Wave 3 at 10:50 a.m., and Wave 4 at 11:15 a.m. Runners must assemble in the Athletes' Village in Hopkinton, transported by bus from Boston Common in wave-specific groups starting at 6:45 a.m., and walk 0.7 miles to the start line. Participants may shift to a later wave or corral but not an earlier one; violations result in disqualification to enforce orderly progression and prevent overcrowding.[38][40]| Division/Program | Start Time (ET) |

|---|---|

| Men's Wheelchair | 9:06 a.m. |

| Women's Wheelchair | 9:09 a.m. |

| Handcycles & Duos | 9:30 a.m. |

| Professional Men | 9:37 a.m. |

| Professional Women | 9:47 a.m. |

| Para Athletics Divisions | 9:50 a.m. |

| Wave 1 (Open) | 10:00 a.m. |

| Wave 2 (Open) | 10:25 a.m. |

| Wave 3 (Open) | 10:50 a.m. |

| Wave 4 (Open) | 11:15 a.m. |

Records, Statistics, and Performance Analysis

The men's open division course record stands at 2:03:02, set by Geoffrey Mutai of Kenya in 2011, though this time does not qualify as an official world record due to the course's point-to-point layout and net elevation drop exceeding World Athletics criteria of 1% maximum decline over the distance.[4] [41] The women's open division course record is 2:17:22, achieved by Sharon Lokedi of Kenya in 2025, surpassing the prior mark of 2:19:59 set by Buzunesh Deba of Ethiopia in 2014 by over two minutes.[42] In the wheelchair divisions, the men's record is 1:17:06 by Marcel Hug of Switzerland (year not specified in primary records but aligned with recent elite performances), while women's wheelchair records reflect similar high-speed adaptations to the course.[4] Masters division records include 2:11:04 for men by John Campbell of New Zealand in 1990 and 2:27:58 for women by Firiya Sultanova-Zhdanova of Russia in 2002.[43]| Division | Record Holder | Time | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men's Open | Geoffrey Mutai (KEN) | 2:03:02 | 2011[4] |

| Women's Open | Sharon Lokedi (KEN) | 2:17:22 | 2025[42] |

| Men's Wheelchair | Marcel Hug (SUI) | 1:17:06 | Recent elite[4] |

| Women's Masters | Firiya Sultanova-Zhdanova (RUS) | 2:27:58 | 2002[43] |

Cultural and Social Elements

Traditions and Spectator Engagement

The Boston Marathon is traditionally held annually on Patriots' Day, the third Monday in April, a Massachusetts state holiday commemorating the Battles of Lexington and Concord that ignited the American Revolutionary War on April 19, 1775.[49] This timing aligns the race with historical reenactments and community events, embedding the event within a broader celebration of regional heritage.[10] The marathon's start in Hopkinton and finish on Boylston Street in Boston have remained consistent since 1897, fostering a sense of continuity and ritual for participants and observers alike.[10] Distinctive rituals include the presentation of olive wreaths to winners, sourced from Marathon, Greece, a practice initiated in 1984 to evoke the ancient origins of the marathon event from the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE.[50] In the lead-up to race day, commemorative banners are displayed along Boston streets, a longstanding annual tradition organized by the Boston Athletic Association (BAA) to build anticipation and honor the event's legacy.[51] Volunteers also plant thousands of daffodils along the route each spring, symbolizing renewal and adding a seasonal flourish to the course.[52] Spectator engagement is intense, with hundreds of thousands lining the 26.2-mile route, particularly at key points like the halfway mark near Wellesley College, where the "Scream Tunnel" has formed since the 1970s.[53] Here, students gather to deliver high-volume cheers, motivational signs, and historically, kisses to runners—though the latter has diminished in recent decades amid evolving social norms—providing a psychological boost around mile 13.[54] The BAA facilitates viewer access via public transit details and road closure maps, encouraging crowds to cluster in areas like Newton Hills and the finish line vicinity for optimal viewing.[55] This communal fervor transforms the race into a citywide spectacle, where spectators' energy—manifested through signs, music, and direct encouragement—contributes to the event's reputation as a participatory cultural phenomenon rather than a isolated athletic contest.[56]Notable Participants and Human Interest Stories

Kathrine Switzer gained international recognition in 1967 as the first woman to officially enter and complete the Boston Marathon, registering under the initials "K.V. Switzer" to circumvent the race's prohibition on female participants.[57] Early in the event on April 19, race co-director Jock Semple attempted to eject her from the course by grabbing her arm, an action captured in photographs that highlighted gender exclusion in distance running.[7] Supported by her boyfriend Thomas Miller, who shoved Semple away, Switzer persisted and finished the 26.2-mile course in about 4 hours and 20 minutes, though her entry was later annulled by officials.[7] This defiance spurred public debate and advocacy, accelerating the inclusion of women as official entrants starting in 1972.[7]

Team Hoyt, formed by Dick Hoyt pushing his son Rick—who has cerebral palsy and uses a head-mounted pointer to operate a custom communication device—completed the Boston Marathon 32 times from 1980 to 2014.[58] Motivated by Rick's request after a benefit run for a lacrosse player in 1977, the pair undertook over 1,100 endurance events together, including 72 marathons, to demonstrate that physical limitations do not preclude participation in athletic challenges.[59] Their consistent finishes, often in the 3-hour range for full marathons despite the added burden of pushing a wheelchair, exemplified parental commitment and inspired adaptive sports initiatives, culminating in a bronze statue dedicated near the race start on April 8, 2013.[60] Dick Hoyt passed away in 2021 at age 80, followed by Rick in 2023 at age 61, yet family members continue the legacy in subsequent races.[61] In 1975, Bob Hall became the first officially sanctioned wheelchair athlete to finish the Boston Marathon, navigating the course in an ordinary folding chair modified for propulsion, which marked the inception of the wheelchair division and expanded accessibility for athletes with mobility impairments.[10] Hall's completion, timed at 2 hours and 58 minutes despite rudimentary equipment and the absence of dedicated divisions, underscored early innovations in adaptive racing that evolved into competitive categories by the 1980s.[10]