Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Breast cancer screening

View on Wikipedia| Breast cancer screening | |

|---|---|

A woman having a mammogram |

Breast cancer screening is the medical screening of asymptomatic, apparently healthy women for breast cancer in an attempt to achieve an earlier diagnosis. The assumption is that early detection will improve outcomes. A number of screening tests have been employed, including clinical and self breast exams, mammography, genetic screening, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging.

A clinical or self breast exam involves feeling the breast for lumps or other abnormalities. Medical evidence, however, does not support its use in women with a typical risk for breast cancer.[1]

Universal screening with mammography is controversial as it may not reduce all-cause mortality and may cause harms through unnecessary treatments and medical procedures. Many national organizations recommend it for most older women. The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening mammography in women at normal risk for breast cancer, every other year between the ages of 40 and 74.[2] Other positions vary from no screening to starting at age 40 and screening yearly.[3][4] Several tools are available to help target breast cancer screening to older women with longer life expectancies.[5] Similar imaging studies can be performed with magnetic resonance imaging but evidence is lacking.[6][7]

Earlier, more aggressive, and more frequent screening is recommended for women at particularly high risk of developing breast cancer, such as those with a confirmed BRCA mutation, those who have previously had breast cancer, and those with a strong family history of breast and ovarian cancer.

Abnormal findings on screening are further investigated by surgically removing a piece of the suspicious lumps (biopsy) to examine them under the microscope. Ultrasound may be used to guide the biopsy needle during the procedure. Magnetic resonance imaging is used to guide treatment, but is not an established screening method for healthy women.

Breast exam

[edit]

Breast examinations (either clinical breast exams (CBE) by a health care provider or by self exams) are highly debated. Like mammography and other screening methods, breast examinations produce false positive results, contributing to harm. The use of screening in women without symptoms and at low risk is thus controversial.[8]

A 2003 Cochrane review found screening by breast self-examination is not associated with lower death rates among women who report performing breast self-examination and does, like other breast cancer screening methods, increase harms, in terms of increased numbers of benign lesions identified and an increased number of biopsies performed.[1] They conclude "at present, breast self-examination cannot be recommended".[1] Another study done by the National Breast Cancer Foundation states that 8 out of 10 lumps found are noncancerous.

On the other hand, Lillie D. Shockney, a Professor from Johns Hopkins University states, 'Forty percent of diagnosed breast cancers are detected by women who feel a lump, so establishing a regular breast self-exam is very important.'[9][1]

There are different tactics on how to go about examining one's breasts. Doctors suggest that you use the pads of your three middle fingers and move them in circular motions starting at the center of the breast and continuing out into the armpit area. Apply different amounts of pressure while conducting the exam. Any lumps, thickenings, hardened knots, or any other breast changes should be brought to the attention of your healthcare provider. It is also important to look for changes in color or shape, nipple discharge, dimpling, and swelling.[9]

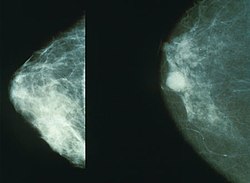

Mammography

[edit]Mammography is a common screening method, since it is relatively fast and widely available in developed countries. Mammography is a type of radiography used on the breasts. It is typically used for two purposes: to aid in the diagnosis of a woman who is experiencing symptoms or has been called back for follow-up views (called diagnostic mammography), and for medical screening of apparently healthy women (called screening mammography).[10]

Mammography is not very useful in finding breast tumors in dense breast tissue characteristic of women under 40 years.[11][12] In women over 50 without dense breasts, breast cancers detected by screening mammography are usually smaller and less aggressive than those detected by patients or doctors as a breast lump. This is because the most aggressive breast cancers are found in dense breast tissue, which mammograms perform poorly on.[11] The European Commission's Scientific Advice Mechanism recommends that MRI scans are used in place of mammography for women with dense breast tissue.[7]

The presumption was that by detecting cancer in an earlier stage, women will be more likely to be cured by treatment. This assertion, however, has been challenged by recent reviews which have found the significance of these net benefits to be lacking for women at average risk of dying from breast cancer.[citation needed]

Mechanism

[edit]

Screening mammography is usually recommended to women who are most likely to develop breast cancer. In general, this includes women who have risk factors such as having a personal or family history of breast cancer or being older women, but not being frail elderly women, who are unlikely to benefit from treatment.

Women who agree to be screened have their breasts X-rayed on a specialized X-ray machine. This exposes the woman's breasts to a small amount of ionizing radiation, which has a very small, but non-zero, chance of causing cancer.

The X-ray image, called a radiograph, is sent to a physician who specializes in interpreting these images, called a radiologist. The image may be on plain photographic film or digital mammography on a computer screen; despite the much higher cost of the digital systems, the two methods are generally considered equally effective. The equipment may use a computer-aided diagnosis system.

There is considerable variation in interpreting the images; the same image may be declared normal by one radiologist and suspicious by another. It can be helpful to compare the images to any previously taken images, as changes over time may be significant.

If suspicious signs are identified in the image, then the woman is usually recalled for a second mammogram, sometimes after waiting six months to see whether the spot is growing, or a biopsy of the breast.[13] Most of these will prove to be false positives, resulting in sometimes debilitating anxiety over nothing. Most women recalled will undergo additional imaging only, without any further intervention. Recall rates are higher in the U.S. than in the UK.[14]

Effectiveness

[edit]On balance, screening mammography in older women increases medical treatment and saves a small number of lives.[3] Usually, it has no effect on the outcome of any breast cancer that it detects. Screening targeted towards women with above-average risk produces more benefit than screening of women at average or low risk for breast cancer.

A 2013 Cochrane review estimated that mammography in women between 50 and 75 years old results in a relative decreased risk of death from breast cancer of 15% and an absolute risk reduction of 0.05%.[3] However, when the analysis included only the least biased trials, women who had regular screening mammograms were just as likely to die from all causes, and just as likely to die specifically from breast cancer, as women who did not. The size of effect might be less in real life compared with the results in randomized controlled trials due to factors such as increased self-selection rate among women concerned and increased effectiveness of adjuvant therapies.[15] The Nordic Cochrane Collection (2012) reviews said that advances in diagnosis and treatment might make mammography screening less effective at saving lives today. They concluded that screening is "no longer effective" at preventing deaths and "it therefore no longer seems reasonable to attend" for breast cancer screening at any age, and warn of misleading information on the internet.[16] The review also concluded that "half or more" of cancers detected with mammography would have disappeared spontaneously without treatment. They found that most of the earliest cell changes found by mammography screening (carcinoma in situ) should be left alone because these changes would not have progressed into invasive cancer.[16]

The accidental harm from screening mammography has been underestimated. Women who have mammograms end up with increased surgeries, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and other potentially procedures resulting from the over-detection of harmless lumps. Many women will experience important psychological distress for many months because of false positive findings.[3] Half of suspicious findings will not become dangerous or will disappear over time.[3] Consequently, the value of routine mammography in women at low or average risk is controversial.[3] With unnecessary treatment of ten women for every one woman whose life was prolonged, the authors concluded that routine mammography may do more harm than good.[3] If 1,000 women in their 50s are screened every year for ten years, the following outcomes are considered typical in the developed world:[17]

- One woman's life will be extended due to earlier detection of breast cancer.

- 2 to 10 women will be overdiagnosed and needlessly treated for cancer that would have stopped growing on its own or otherwise caused no harm during the woman's lifetime.

- 5 to 15 women will be treated for breast cancer, with the same outcome as if cancer had been detected after symptoms appeared.

- 500 will be incorrectly told they might have breast cancer (false positive).[18]

- 125 to 250 will undergo breast biopsy.

The outcomes are worse for women in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, as they are far less likely to have a life-threatening breast cancer, and more likely to have dense breasts that make interpreting the mammogram more difficult. Among women in their 60s, who have a somewhat higher rate of breast cancer, the proportion of positive outcomes to harms are better:[19]

- For women in their 40s: About 2,000 women would need to be screened every year for 10 years to prevent one death from breast cancer.[19] 1,000 of these women would experience false positives, and 250 healthy women would undergo unnecessary biopsies.

- For women in their 50s: About 1,350 women would need to be screened for every year for 10 years to prevent one death from breast cancer. Half of these women would experience false positives, and one-quarter would undergo unnecessary biopsies.

- For women in their 60s: About 375 women would need to be screened for every year for 10 years to prevent one death from breast cancer. Half of these women would experience false positives, and one-quarter would undergo unnecessary biopsies.

Mammography is not generally considered as an effective screening technique for women at average or low risk of developing cancer who are less than 50 years old. For normal-risk women 40 to 49 years of age, the risks of mammography outweigh the benefits,[20] and the US Preventive Services Task Force says that the evidence in favor of routine screening of women under the age of 50 is "weak".[21] Part of the difficulty in interpreting mammograms in younger women stems from breast density. Radiographically, a dense breast has a preponderance of glandular tissue, and younger age or estrogen hormone replacement therapy contribute to mammographic breast density. After menopause, the breast glandular tissue gradually is replaced by fatty tissue, making mammographic interpretation much more accurate.

Recommendations

[edit]Recommendations to attend to mammography screening vary across countries and organizations, with the most common difference being the age at which screening should begin, and how frequently or if it should be performed, among women at typical risk for developing breast cancer.

In England, all women were invited for screening once every three years beginning at age 50,.[22] There is a trial in progress to assess the risks and benefits of offering screening to women aged 47 to 49. Some other organizations recommend mammograms begin as early as age 40 in normal-risk women, and take place more frequently, up to once each year. Women at higher risk may benefit from earlier or more frequent screening. Women with one or more first-degree relatives (mother, sister, daughter) with premenopausal breast cancer often begin screening at an earlier age, perhaps at an age 10 years younger than the age when the relative was diagnosed with breast cancer.

As of 2009 the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women over the age of 50 receive mammography once every two years.[21]

In March 2022, the European Commission's Scientific Advice Mechanism recommended extending screening to women in their mid-40s.[7]

The Cochrane Collaboration (2013) states that the best quality evidence neither demonstrates a reduction in either cancer specific, nor a reduction in all-cause mortality from screening mammography.[3] When less rigorous trials are added to the analysis there is a reduction in breast cancer specific mortality of 0.05% (a relative decrease of 15%).[3] Screening results in a 30% increase in rates of over-diagnosis and over-treatment, resulting in the view that it is not clear whether mammography screening does more good or harm.[3] On their Web site, Cochrane currently concludes that, due to recent improvements in breast cancer treatment, and the risks of false positives from breast cancer screening leading to unnecessary treatment, "it therefore no longer seems reasonable to attend for breast cancer screening" at any age.[16][23]

Breast density

[edit]

Breasts are made up of breast tissue, connective tissue, and adipose (fat) tissue. The amount of each of the three types of tissue varies from person to person. Breast density is a measurement of relative amounts of these three tissues in breasts, as determined by their appearance on an X-ray image. Breast and connective tissues are radiographically denser (they produce a brighter white on an X-ray) than adipose tissue on a mammogram, so a person with more breast tissue and/or more connective tissue is said to have greater breast density. Breast density is assessed by mammography and expressed as a percentage of the mammogram occupied by radiologically dense tissue (percent mammographic density or PMD).[24] About half of middle-aged women have dense breasts, and breasts generally become less dense as they age. Higher breast density is an independent risk factor for breast cancer. Further, breast cancers are difficult to detect through mammograms in women with high breast density because most cancers and dense breast tissues have a similar appearance on a mammogram. As a result, higher breast density is associated with a higher rate of false negatives (missed cancers).[25] Because of the importance of breast density as a risk indicator and as a measure of diagnostic accuracy, automated methods have been developed to facilitate assessment and reporting for mammography,[26][27] and tomosynthesis.[28]

Health programs

[edit]United States

[edit]In 2005, about 68% of all U.S. women age 40–64 had a mammogram in the past two years (75% of women with private health insurance, 56% of women with Medicaid insurance, 38% of currently uninsured women, and 33% of women uninsured for more than 12 months).[29] All U.S. states except Utah require private health insurance plans and Medicaid to pay for breast cancer screening.[30] As of 1998, Medicare (available to those aged 65 or older or who have been on Social Security Disability Insurance for over 2 years) pays for annual screening mammography in women aged 40 or older.

Canada

[edit]Three out of twelve (3/12) breast cancer screening programs in Canada offer clinical breast examinations.[31] All twelve offer screening mammography every two years for women aged 50–69, while nine out of twelve (9/12) offer screening mammography for women aged 40–49.[31] In 2003, about 61% of women aged 50–69 in Canada reported having had a mammogram within the past two years.[32]

United Kingdom

[edit]The UK's NHS Breast Screening Programme, the first of its kind in the world, began in 1988 and achieved national coverage in the mid-1990s. It provides free breast cancer screening mammography every three years for all women in the UK aged from 50 and up to their 71st birthday. The NHS Breast Screening Programme is supporting a research study trial to assess the risks (i.e. the chances of being diagnosed and treated for a non-life-threatening cancer) and benefits (i.e. the chances of saving life) in women aged 47 to 49 and 71 to 73 (Public Health England 2017).

As of 2006, about 76% of women aged 53–64 resident in England had been screened at least once in the previous three years.[33] However a 2016 UK-based study has also highlighted that the uptake of breast cancer screening among women living with severe mental illness (SMI) is lower than patients of the same age in the same population, without SMI.[34] In Northern Ireland women with mental health problems were shown to be less likely to attend screening for breast cancer, than women without. The lower attendance numbers remained the same even when marital status and social deprivation were taken into account.[35][36] People from minority ethnic communities are also less likely to attend cancer screening. In the UK, women of South Asian heritage are the least likely to attend breast cancer screening.[37][38][39]

After information technology problems affected the recall system in England an internal inquiry by Public Health England and an independent inquiry were established and the National Audit Office started an investigation.[40]

Australia

[edit]The Australian national breast screening program, BreastScreen Australia, was commenced in the early 1990s and invites women aged 50–74 to screening every 2 years. No routine clinical examination is performed, and the cost of screening is free to the point of diagnosis.

Singapore

[edit]The Singapore national breast screening program, BreastScreen Singapore, started in 2002. It is the only publicly funded national breast screening program in Asia and enrolls women aged 50–64 for screening every two years. Like the Australian system, no clinical examination is performed routinely. Unlike most national screening systems, however, clients have to pay half of the cost of the screening mammogram; this is in line with the Singapore health system's core principle of co-payment for all health services.

Criticisms

[edit]Most women significantly overestimate both their own risk of dying from breast cancer and the effect screening mammography could have on it.[41] Some researchers worry that if women correctly understood that screening programs offer a small, but statistically significant benefit, more women would refuse to participate.[41]

The contribution of mammography to the early diagnosis of cancer is controversial, and for those found with benign lesions, mammography can create a high psychological and financial cost. Most women participating in mammography screening programs accept the risk of false positive recall, and the majority do not find it very distressing.[citation needed] Many patients find the recall very frightening, and are intensely relieved to discover that it was a false positive, as about 90% of women do.[42]

A major effect of routine breast screening is to greatly increase the rate of early breast cancer detection, in particular for non-invasive ductal carcinoma in situ, sometimes called "pre-breast cancer", which almost never forms a lump and which generally cannot be detected except through mammography. While this ability to detect such very early breast malignancies is at the heart of claims that screening mammography can improve survival from breast cancer, it is also controversial. This is because a very large proportion of such cases will not progress to kill the patient, and thus mammography cannot be genuinely claimed to have saved any lives in such cases; in fact, it would lead to increased sickness and unnecessary surgery for such patients.

Consequently, finding and treating many cases of ductal carcinoma in situ represents overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Treatment is given to all women with ductal carcinoma in situ because it is currently impossible to predict who will have an indolent, non-fatal course, and which few will progress to invasive cancer and premature death if left untreated. Consequently, all patients with ductal carcinoma in situ are treated in much the same way, with at least wide local excision, and sometimes mastectomy if it is very extensive. The cure rate for ductal carcinoma in situ if treated appropriately is extremely high, partly because the majority of cases were harmless in the first place.

The phenomenon of finding pre-invasive malignancy or nonmalignant benign disease is commonplace in all forms of cancer screening, including pap smears for cervical cancer, fecal occult blood testing for colon cancer, and prostate-specific antigen testing for prostate cancer. All of these tests have the potential to detect asymptomatic cancers, and all of them have a high rate of false positives and lead to invasive procedures that are unlikely to benefit the patient.

Risk-based screening

[edit]Risk-based screening uses risk assessment of a woman's five-year and lifetime risk of developing breast cancer to issue personalized screening recommendations of when to start, stop, and how often to screen.[43] In general, women with low risk are recommended to screen less frequently, while screening is intensified in those at high risk. The NCI (National Cancer Institute) provides a free breast cancer risk assessment tool online that utilizes the Gail Model to predict risk of developing invasive breast cancer based on a woman's personal information.[44] This tool has been found to underestimate the risk of breast cancer in non-white women.[44] The hypothesis is that focusing screening on women most likely to develop invasive breast cancer will reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

The Wisdom Study,[a] currently ongoing in California as of March 2025[update], is first clinical trial testing the safety and efficacy of risk-based screening compared to annual screening.[45]

Molecular breast imaging

[edit]Molecular breast imaging is a nuclear medicine technique that is currently under study. It shows promising results for imaging people with dense breast tissue and may have accuracies comparable to MRI.[46] It may be better than mammography in some people with dense breast tissue, detecting two to three times more cancers in this population.[46] It however carries a greater risk of radiation damage making it inappropriate for general breast cancer screening.[47] It is possible to reduce the dose of radiation used.[48]

An earlier alternative technique suited to dense breast tissue, scintimammography is now not recommended by the American Cancer Society, which states, "This test cannot show whether an abnormal area is cancer as accurately as a mammogram, and it's not used as a screening test. Some radiologists believe this test may be helpful in looking at suspicious areas found by mammogram. But the exact role of scintimammography is still unclear."[49]

Ultrasonography

[edit]Medical ultrasonography is a diagnostic aid to mammography. Adding ultrasonography testing for women with dense breast tissue increases the detection of breast cancer, but also increases false positives.[50][51] Ultrasonography is indicated in women under 40-45 years old that present signs such as: palpable lump on breast or axillary area, skin retraction or discharge from the nipples. It can also be used in pregnant or lactating women.[52]

The ultrasonography is the preferred method for individuals who need repeated scans over a certain period of time due to the lack of ionizing radiation. Disadvantages include a low ability to detect microcalcifications, a possible early sign of cancer.[53]

Contrast-enhanced mammography

[edit]Contrast-enhanced mammography is an advanced imaging technique that employs iodinated contrast agents to visualize breast neovascularization, functioning similarly to magnetic resonance imaging. Tumor-associated angiogenesis often results in leaky blood vessels, allowing contrast material to accumulate within the tumor tissue and produce an iodine-enhanced image. This enhances the visibility of malignancies that might otherwise be obscured by dense breast tissue. Contrast-enhanced mammography is also referred to as contrast-enhanced spectral mammography, contrast-enhanced digital mammography, or contrast-enhanced dual-energy mammography.[54]

A large randomized controlled trial published in The Lancet in 2025 found that contrast-enhanced mammography detects significantly more invasive breast cancers in women with dense breast tissue than standard mammography or ultrasound. Conducted across 10 U.K. screening sites with over 9,000 participants, the study reported that contrast-enhanced mammography identified 15.7 invasive cancers per 1,000 exams, compared to 4.2 for ultrasound and 15 for MRI, with no statistically significant difference between contrast-enhanced mammography and MRI. Contrast-enhanced mammography was also found to be more cost-effective and accessible than MRI. Advocates suggest contrast-enhanced mammography could improve early detection and outcomes for women with dense breasts, but acknowledge risks of overdiagnosis.[55]

Magnetic resonance imaging

[edit]Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been shown to detect cancers not visible on mammograms. The chief strength of breast MRI is its very high negative predictive value. A negative MRI can rule out the presence of cancer to a high degree of certainty, making it an excellent tool for screening in patients at high genetic risk or radiographically dense breasts, and for pre-treatment staging where the extent of disease is difficult to determine on mammography and ultrasound. MRI can diagnose benign proliferative change, fibroadenomas, and other common benign findings at a glance, often eliminating the need for costly and unnecessary biopsies or surgical procedures. The spatial and temporal resolution of breast MRI has increased markedly in recent years, making it possible to detect or rule out the presence of small in situ cancers, including ductal carcinoma in situ.

Despite the aids provided from MRIs, there are some disadvantages. For example, although it is 27–36% more sensitive, it has been claimed to be less specific than mammography.[56] As a result, MRI studies may have up to 30% more false positives, which may have undesirable financial and psychological costs on the patient. Also, MRI procedures are expensive and include an intravenous injection of a gadolinium contrast, which has been implicated in a rare reaction called nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.[56] Other patients with a history of renal failure/disease are not able to undergo MRI scans. Breast MRI is not recommended for screening all breast cancer patients, yet limited to patients with high risk of developing breast cancer that may have high familial risk or mutations in BCRA1/2 genes.[57] Breast MRI is not a perfect tool despite its increased sensitivity for detecting breast cancer masses when compared to mammography. This due to the ability of MRIs to miss some cancers that would have been detected with conventional mammography. As a result, MRI screening for breast cancer is most effective as a combination with other tests and for certain breast cancer patients.[58][57] In contrast, the use of MRIs are often limiting to patients with any body metal integration such as patients with tattoos, pacemakers, tissue expanders, and so on.

Proposed indications for using MRI for screening include:[59]

- Strong family history of breast cancer

- Patients with BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 oncogene mutations

- Evaluation of women with breast implants

- History of previous lumpectomy or breast biopsy surgeries

- Axillary metastasis with an unknown primary tumor

- Very dense or scarred breast tissue[7]

In addition, breast MRI may be helpful for screening in women who have had breast augmentation procedures involving intramammary injections of various foreign substances that may mask the appearances of breast cancer on mammography and/or ultrasound. These substances include silicone oil and polyacrylamide gel.

BRCA testing

[edit]Genetic testing does not detect cancers, but may reveal a propensity to develop cancer. Women who are known to have a higher risk of developing breast cancer usually undertake more aggressive screening programs. However, research has shown that genetic screening needs to be adapted for use in women from different ethnic groups. A study in the UK found that two established risk scores – called SNP18 and SNP143 – are inaccurate and exaggerate risk in Black, Asian, mixed-race and Ashkenazi Jewish women.[60][61]

A clinical practice guideline by the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against routine referral for genetic counseling or routine testing for BRCA mutations, on fair evidence that the harms outweigh the benefits.[62] It also encourages a referral for counseling and testing in women who have a family history that indicates they have an increased risk of a BRCA mutation, on fair evidence of benefit.[62] About 2% of American women have family histories that indicate an increased risk of having a medically significant BRCA mutation.[62]

Other

[edit]- The nipple aspirate test is not indicated for breast cancer screening.[63][64]

- Optical imaging, also known as diaphanography (DPG), multi-scan transillumination, and light scanning, is the use of transillumination to distinguish tissue variations. It is in the early stage of study.[65]

- A test of anti-malignin antibody in serum has been studied for breast cancer screening with mixed results.[66]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier for the Wisdom Study is: NCT02620852. The official website for this study is: www.thewisdomstudy.org/

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Kösters JP, Gøtzsche PC (2003). Kösters JP (ed.). "Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (2) CD003373. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003373. PMC 7387360. PMID 12804462.

- ^ "Final Recommendation Statement for Breast Cancer Screening". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 30 April 2024. Archived from the original on 20 July 2025. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ (June 2013). "Screening for breast cancer with mammography". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6) CD001877. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5. PMC 6464778. PMID 23737396.

- ^ "Guidelines". www.acraccreditation.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Schonberg M. Breast cancer screening: at what age to stop? Archived 2011-10-04 at the Wayback Machine Consultant. 2010;50(May):196-205.

- ^ Siu AL (February 2016). "Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (4): 279–96. doi:10.7326/M15-2886. PMID 26757170.

- ^ a b c d "Improving cancer screening in the European Union". 2 March 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Saslow D, Hannan J, Osuch J, Alciati MH, Baines C, Barton M, Bobo JK, Coleman C, Dolan M, Gaumer G, Kopans D, Kutner S, Lane DS, Lawson H, Meissner H, Moorman C, Pennypacker H, Pierce P, Sciandra E, Smith R, Coates R (2004). "Clinical breast examination: practical recommendations for optimizing performance and reporting". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 54 (6): 327–44. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.6.327. PMID 15537576.

- ^ a b "Breast Self-Exam". Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Mammography". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ^ a b The Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Book. RosettaBooks. 2012-11-16. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7953-3430-6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Reynolds H (2012-08-07). The Big Squeeze: a social and political history of the controversial mammogram. Cornell University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8014-6556-7.

- ^ Croswell JM, Kramer BS, Kreimer AR, Prorok PC, Xu JL, Baker SG, Fagerstrom R, Riley TL, Clapp JD, Berg CD, Gohagan JK, Andriole GL, Chia D, Church TR, Crawford ED, Fouad MN, Gelmann EP, Lamerato L, Reding DJ, Schoen RE (2009). "Cumulative incidence of false-positive results in repeated, multimodal cancer screening". Annals of Family Medicine. 7 (3): 212–22. doi:10.1370/afm.942. PMC 2682972. PMID 19433838.

- ^ Smith-Bindman R, Ballard-Barbash R, Miglioretti DL, Patnick J, Kerlikowske K (2005). "Comparing the performance of mammography screening in the USA and the UK". Journal of Medical Screening. 12 (1): 50–4. doi:10.1258/0969141053279130. PMID 15814020. S2CID 20519761.

- ^ Harris R, Yeatts J, Kinsinger L (September 2011). "Breast cancer screening for women ages 50 to 69 years a systematic review of observational evidence". Preventive Medicine. 53 (3): 108–14. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.004. PMID 21820465.

- ^ a b c "Mammography-leaflet; Screening for breast cancer with mammography" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- ^ Welch, H. Gilbert; Woloshin, Steve; Schwartz, Lisa A. (2011). Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. Beacon Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8070-2200-9.

- ^ "Information on Mammography for Women Aged 40 and Older". 2010-01-05. Archived from the original on 2015-05-10. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ a b Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L (November 2009). "Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 151 (10): 727–37, W237–42. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00009. PMC 2972726. PMID 19920273.

- ^ Armstrong K, Moye E, Williams S, Berlin JA, Reynolds EE (April 2007). "Screening mammography in women 40 to 49 years of age: a systematic review for the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (7): 516–26. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00008. PMID 17404354.

- ^ a b US Preventive Services Task Force (November 2009). "Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 151 (10): 716–26, W–236. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. PMID 19920272. Archived from the original on 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "Why are women under 50 not routinely invited for breast screening?" Archived 2024-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, Public Health England, accessed 19 May 2014

- ^ "Screening for breast cancer with mammography". cochrane.dk. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- ^ Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Yaffe MJ, Minkin S (2011-11-01). "Mammographic density and breast cancer risk: current understanding and future prospects". Breast Cancer Research. 13 (6) 223. doi:10.1186/bcr2942. PMC 3326547. PMID 22114898.

- ^ Houssami N, Kerlikowske K (June 2012). "The Impact of Breast Density on Breast Cancer Risk and Breast Screening". Current Breast Cancer Reports. 4 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1007/s12609-012-0070-z. S2CID 71425894.

- ^ Yaffe MJ (2008). "Mammographic density. Measurement of mammographic density". Breast Cancer Research. 10 (3) 209. doi:10.1186/bcr2102. PMC 2481498. PMID 18598375.

- ^ Sacchetto D, Morra L, Agliozzo S, Bernardi D, Björklund T, Brancato B, et al. (January 2016). "Mammographic density: Comparison of visual assessment with fully automatic calculation on a multivendor dataset". European Radiology. 26 (1): 175–183. arXiv:1811.05324. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-3784-2. PMID 25929945. S2CID 19841721.

- ^ Fredenberg E, Berggren K, Bartels M, Erhard K (2016). "Volumetric Breast-Density Measurement Using Spectral Photon-Counting Tomosynthesis: First Clinical Results". In Tingberg A, Lång K, Timberg P (eds.). Breast Imaging. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 9699. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 576–584. arXiv:2101.02758. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41546-8_72. ISBN 978-3-319-41545-1. S2CID 1257696. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- ^ Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, Cokkinides V, DeSantis C, Bandi P, Siegel R, Stewart A, Jemal A (January–February 2008). "Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 58 (1): 9–31. doi:10.3322/CA.2007.0011. PMID 18096863. S2CID 24085070.

- ^ Kaiser Family Foundation (December 31, 2006). "State Mandated Benefits: Cancer Screening for Women, 2006". Archived from the original on October 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "Organized Breast Cancer Screening Programs in Canada REPORT ON PROGRAM PERFORMANCE IN 2007 AND 2008" (PDF). cancerview.ca. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. February 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Canadian Cancer Society (April 2006). "Canadian Cancer Statistics, 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-29.

- ^ The Information Centre (NHS) (March 23, 2007). "Breast Screening Programme 2005/06". Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ Woodhead C, Cunningham R, Ashworth M, Barley E, Stewart RJ, Henderson MJ (October 2016). "Cervical and breast cancer screening uptake among women with serious mental illness: a data linkage study". BMC Cancer. 16 (1) 819. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2842-8. PMC 5073417. PMID 27769213.

- ^ "Breast cancer screening: women with poor mental health are less likely to attend appointments". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). 2021-06-21. doi:10.3310/alert_46400. S2CID 241919707. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ Ross E, Maguire A, Donnelly M, Mairs A, Hall C, O'Reilly D (June 2020). "Does poor mental health explain socio-demographic gradients in breast cancer screening uptake? A population-based study". European Journal of Public Health. 30 (3): 396–401. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckz220. PMID 31834366.

- ^ "Cultural and language barriers need to be addressed for British-Pakistani women to benefit fully from breast screening". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). 2020-09-15. doi:10.3310/alert_41135. S2CID 241324844. Archived from the original on 2022-03-14. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ Woof VG, Ruane H, Ulph F, French DP, Qureshi N, Khan N, et al. (September 2020). "Engagement barriers and service inequities in the NHS Breast Screening Programme: Views from British-Pakistani women". Journal of Medical Screening. 27 (3): 130–137. doi:10.1177/0969141319887405. PMC 7645618. PMID 31791172.

- ^ Woof VG, Ruane H, French DP, Ulph F, Qureshi N, Khan N, et al. (May 2020). "The introduction of risk stratified screening into the NHS breast screening Programme: views from British-Pakistani women". BMC Cancer. 20 (1) 452. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-06959-2. PMC 7240981. PMID 32434564.

- ^ "National Audit Office investigating NHS screening programmes". Health Service Journal. 24 October 2018. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Women 'misjudge screening benefits'". BBC News. 15 October 2001. Archived from the original on 2003-04-25. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ Welch, 2011. pp. 177–178.

- ^ Shieh Y, Eklund M, Madlensky L, Sawyer SD, Thompson CK, Stover Fiscalini A, Ziv E, Van't Veer LJ, Esserman LJ, Tice JA (January 2017). "Breast Cancer Screening in the Precision Medicine Era: Risk-Based Screening in a Population-Based Trial". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 109 (5) djw290. doi:10.1093/jnci/djw290. PMID 28130475.

- ^ a b "About the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Calculator (The Gail Model)". National Cancer Institute. October 11, 2023. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ Fernandez, Elizabeth (2023-02-14). ""Smarter" Breast Cancer Screening Measures Risk Down to Your DNA". www.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ a b O'Connor M, Rhodes D, Hruska C (August 2009). "Molecular breast imaging". Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 9 (8): 1073–80. doi:10.1586/era.09.75. PMC 2748346. PMID 19671027.

- ^ Moadel RM (May 2011). "Breast cancer imaging devices". Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 41 (3): 229–41. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2010.12.005. PMID 21440698.

- ^ O'Connor MK, Li H, Rhodes DJ, Hruska CB, Clancy CB, Vetter RJ (December 2010). "Comparison of radiation exposure and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from mammography and molecular imaging of the breast". Medical Physics. 37 (12): 6187–98. Bibcode:2010MedPh..37.6187O. doi:10.1118/1.3512759. PMC 2997811. PMID 21302775.

- ^ "Experimental and other breast imaging". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, Mendelson EB, Lehrer D, Böhm-Vélez M, Pisano ED, Jong RA, Evans WP, Morton MJ, Mahoney MC, Larsen LH, Barr RG, Farria DM, Marques HS, Boparai K (May 2008). "Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer". JAMA. 299 (18): 2151–63. doi:10.1001/jama.299.18.2151. PMC 2718688. PMID 18477782. Review in: J Fam Pract. 2008 Aug;57(8):508 Archived 2017-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, Jong RA, Pisano ED, Barr RG, Böhm-Vélez M, Mahoney MC, Evans WP, Larsen LH, Morton MJ, Mendelson EB, Farria DM, Cormack JB, Marques HS, Adams A, Yeh NM, Gabrielli G (April 2012). "Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk". JAMA. 307 (13): 1394–404. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.388. PMC 3891886. PMID 22474203.

- ^ Malherbe K, Tafti D. Breast Ultrasound. [Updated 2024 Jan 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557837/

- ^ Iacob, R.; Iacob, E.R.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Ghenciu, D.M.; Cocolea, D.M.; Constantinescu, A.; Ghenciu, L.A.; Manolescu, D.L. Evaluating the Role of Breast Ultrasound in Early Detection of Breast Cancer in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11030262

- ^ Jochelson, Maxine S.; Lobbes, Marc B.I. (April 2021). "Contrast-enhanced Mammography: State of the Art". Radiology. 299 (1): 36–48. doi:10.1148/radiol.2021201948. ISSN 0033-8419. PMC 7997616. PMID 33650905.

- ^ Rabin, Roni Caryn (2025-05-23). "One Type of Mammogram Proves Better for Women With Dense Breasts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2025-05-24.

- ^ a b Hrung JM, Sonnad SS, Schwartz JS, Langlotz CP (July 1999). "Accuracy of MR imaging in the work-up of suspicious breast lesions: a diagnostic meta-analysis". Academic Radiology. 6 (7): 387–97. doi:10.1016/s1076-6332(99)80189-5. PMID 10410164.

- ^ a b Jochelson MS, Pinker K, Dershaw DD, Hughes M, Gibbons GF, Rahbar K, Robson ME, Mangino DA, Goldman D, Moskowitz CS, Morris EA, Sung JS (December 2017). "Comparison of screening CEDM and MRI for women at increased risk for breast cancer: A pilot study". European Journal of Radiology. 97: 37–43. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.10.001. PMID 29153365.

- ^ "Breast MRI for Screening". breastcancer.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-21. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ Morrow M (December 2004). "Magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer: one step forward, two steps back?". JAMA. 292 (22): 2779–80. doi:10.1001/jama.292.22.2779. PMID 15585740.

- ^ "Ethnicity influences genetic risk scores for breast cancer". NIHR Evidence. 2022-03-28. doi:10.3310/alert_49859. S2CID 247830445. Archived from the original on 2022-08-05. Retrieved 2022-08-05.

- ^ Evans DG, van Veen EM, Byers H, Roberts E, Howell A, Howell SJ, et al. (January 2022). "The importance of ethnicity: Are breast cancer polygenic risk scores ready for women who are not of White European origin?". International Journal of Cancer. 150 (1): 73–79. doi:10.1002/ijc.33782. PMC 9290473. PMID 34460111.

- ^ a b c "Genetic Risk Assessment and BRCA Mutation Testing for Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility: Recommendation Statement". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. United States Preventive Services Task Force. September 2005. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ^ "Breast Cancer Screening - Nipple Aspirate Test Is Not An Alternative To Mammography: FDA Safety Communication". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "Nipple Aspirate Test is No Substitute for Mammogram". FDA. 2019-02-09. Archived from the original on 2018-03-09. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ^ Godavarty A, Rodriguez S, Jung YJ, Gonzalez S (2015). "Optical imaging for breast cancer prescreening". Breast Cancer: Targets and Therapy. 7: 193–209. doi:10.2147/BCTT.S51702. PMC 4516032. PMID 26229503.

- ^ Harman, S. Mitchell; Gucciardo, Frank; Heward, Christopher B.; Granstrom, Per; Barclay-White, Belinda; Rogers, Lowell W.; Ibarra, Julio A. (October 2005). "Discrimination of breast cancer by anti-malignin antibody serum test in women undergoing biopsy". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 14 (10): 2310–2315. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0802. ISSN 1055-9965. PMID 16214910. S2CID 9997137.

External links

[edit]- Archived 2014-05-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Breast cancer screening page from the National Cancer Institute

- Breast Cancer Screening from AARP.org

- Breast cancer screening statistics (Eurostat - Statistics Explained, EHIS WAVE I data collection 2008)

- Comprehensive evidence review of cancer screening programmes from EU's Scientific Advice Mechanism

Breast cancer screening

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Development and Initial Trials

The concept of using mammography for breast cancer screening emerged in the mid-20th century, building on earlier diagnostic applications of X-ray imaging to the breast dating back to the 1930s, when radiologist Stafford L. Warren demonstrated its potential for detecting tumors through soft-tissue visualization.[9] By the 1950s, improvements in X-ray technology and film processing enabled routine imaging, prompting interest in population-based screening rather than solely symptomatic diagnosis, though initial adoption was limited by radiation concerns and lack of randomized evidence.[10] In 1965, Charles Gros in France developed the first dedicated mammography unit, incorporating a molybdenum anode to reduce radiation dose and enhance image contrast for non-calcified lesions, marking a technical milestone that facilitated broader screening feasibility.[9] The first randomized controlled trial evaluating mammography screening, the Health Insurance Plan (HIP) study, began enrollment in December 1963 in New York City, involving approximately 62,000 women aged 40-64 insured through the HIP program, randomized into screened and control groups.[11] The intervention arm received annual screening with mammography combined with clinical breast examination for four years, using low-dose techniques adapted from diagnostic radiology to minimize exposure, which was estimated at about 6-8 rads per exam initially.[12] Long-term follow-up through 1982 revealed a 30% reduction in breast cancer mortality among screened women for cancers diagnosed within five years of entry, with benefits persisting up to 18 years, though absolute mortality reductions were modest due to the trial's small number of events (about 150 breast cancer deaths total).[13] This trial established preliminary causal evidence for screening's role in early detection and stage shift, influencing subsequent guidelines despite criticisms of its non-contemporary equipment and combined modality design.[14] Subsequent early trials in the late 1960s and 1970s, such as non-randomized studies in the U.S. and initial European efforts, built on HIP's framework but faced challenges including variable radiation doses and detection rates for small tumors under 1 cm, which were often missed without modern digital enhancements.[15] These initial efforts highlighted mammography's sensitivity for microcalcifications associated with ductal carcinoma in situ but underscored the need for randomized designs to isolate screening's independent effect from examination alone, setting the stage for larger European trials in the 1970s-1980s.[16]Evolution of Guidelines and Technology

Mammography technology originated in the early 20th century with Albert Salomon's 1913 use of X-rays to examine excised breast tissue, but practical clinical application emerged in the 1950s when Stafford Warren and Robert Egan refined techniques for detecting non-palpable tumors using lower-dose dedicated equipment.[9] The first randomized controlled trial, the Health Insurance Plan (HIP) study launched in 1963, screened 62,000 women aged 40-64 and demonstrated a 30% reduction in breast cancer mortality after 18 years of follow-up, establishing mammography's potential despite limitations in trial design such as non-blinded assessments.[17] Subsequent trials, including the Swedish Two-County Trial (1977-1984) involving 77,080 women, confirmed a 29% mortality reduction in invited women aged 40-74, providing robust evidence that propelled widespread adoption.[18] Guideline evolution reflected accumulating trial data balancing benefits against harms like false positives and overdiagnosis. The American Cancer Society (ACS) initially recommended mammography optionally from age 50 in the 1970s, shifting to baseline screening at 35-39 and annual from 50+ by 1980, then annual from age 40 in 1997 based on emerging evidence of efficacy in younger women.[19] In 2015, ACS updated to optional annual screening from 40-44, annual 45-54, and biennial or annual from 55+, incorporating life expectancy considerations.[19] The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed biennial screening for ages 50-69 in 1986, extending to 40-74 with individual decision-making for 40-49 in 2002; a controversial 2009 revision de-emphasized screening under 50 due to smaller absolute benefits and higher harms, but 2024 guidelines reinstated biennial screening from age 40-74 citing rising incidence in younger women and trial data showing consistent relative risk reductions.[6][20] Technological advancements paralleled guideline refinements, transitioning from screen-film mammography dominant through the 1990s to digital systems approved by the FDA in 2000, which improved detection in dense breasts via computer-aided processing.[21] Digital breast tomosynthesis (3D mammography), FDA-approved in 2011, reduced false positives by 15-40% and increased cancer detection by 1-2 per 1,000 screens in observational studies, leading to its integration into guidelines as an option by 2018.[22] Recent innovations include AI algorithms, with a 2025 trial showing 17.6% higher detection rates when assisting radiologists, though randomized evidence on mortality impact remains pending.[23] These developments address longstanding limitations in sensitivity for dense tissue, comprising 40-50% of women under 50.[24]Rationale and Evidence Base

Mortality Reduction from Screening

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials indicate that mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality by approximately 20% in women aged 50-69 years, with relative risk (RR) estimates ranging from 0.73 to 0.86 depending on the specific trials included.[8][25] A 2024 systematic review of randomized trials reported an overall RR of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.68-0.89) for breast cancer mortality in screened versus unscreened groups, confirming a statistically significant benefit.00181-1/fulltext)| Trial/Meta-Analysis | Age Group | Follow-up Period | Breast Cancer Mortality RR (95% CI) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swedish Two-County Trial | 40-74 years | >20 years | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) overall; 0.71 for 50-69 years | Cluster-randomized; highly significant reduction confirmed by independent committees; one of the most robust trials due to low contamination.[26][27] |

| Myers et al. (2016) Meta-Analysis (8 RCTs) | 50-59 years | Variable | 0.86 (0.75-0.99) | Reduction statistically significant; smaller effect than in older groups.[8] |

| Myers et al. (2016) Meta-Analysis (8 RCTs) | 60-69 years | Variable | 0.73 (0.59-0.91) | Larger reduction; consistent across multiple trials.[8] |

| Independent UK Panel (2012, cited in updates) | 50-69 years | Long-term | ~0.80 | Emphasizes 20% relative reduction; absolute benefit ~1 death averted per 1,000-2,000 women screened over 10-15 years.30398-3/fulltext) |

Detection of Precancerous Lesions and Stage Shift

Breast cancer screening, particularly via mammography, has substantially increased the detection of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a non-invasive lesion considered precancerous, which prior to widespread screening accounted for only 0.8–5% of breast malignancies but now comprises 20–25% of screen-detected cases.[29] The sensitivity of mammography for DCIS exceeds that for invasive breast cancer, with studies reporting detection rates up to 90% for microcalcifications indicative of high-grade DCIS.[30] However, the natural history of DCIS remains uncertain, as modeling and autopsy studies suggest 30–50% of untreated low-grade lesions may regress or remain indolent without progressing to invasion, raising concerns of overdiagnosis where screening identifies lesions that would never cause harm.[31] Systematic reviews estimate that DCIS contributes significantly to overdiagnosis rates of 20–50% in screened populations, prompting debates on whether routine treatment of all detected DCIS prevents meaningful progression or leads to unnecessary interventions like mastectomy or radiation.[32][33] Screening-induced stage shift refers to the downward migration of breast cancer diagnoses to earlier stages, reducing the proportion of advanced (stage III–IV) cases at detection. In organized screening programs, annual mammography has been associated with 20–40% fewer interval cancers and a higher yield of stage 0–I tumors compared to biennial or no screening, based on cohort analyses of over 1 million women.[34] For instance, participation in consecutive screening rounds correlates with a 41% reduction in advanced-stage diagnoses and fatal outcomes within 10 years, attributed partly to earlier intervention.[35] Yet, this shift must be interpreted cautiously due to length-time bias, where slower-growing tumors are preferentially detected, and lead-time bias, which inflates survival estimates without altering mortality timelines; randomized trials confirm stage shifts but attribute only modest net mortality reductions (15–25%) after adjusting for these artifacts and improved adjuvant therapies.[36][37] Empirical data from long-term follow-up indicate that while stage shift facilitates localized treatment, its causal role in population-level mortality decline is confounded by concurrent advances in systemic therapies, with some analyses estimating screening's direct contribution at under 10% in modern eras.[38]Primary Screening Modalities

Mammography

Mammography is a radiographic technique employing low-dose X-rays to visualize breast tissue for the detection of abnormalities, particularly early-stage cancers not palpable on clinical examination. It remains the cornerstone of population-based breast cancer screening programs worldwide, with digital mammography supplanting analog film-screen systems since the early 2000s due to improved image quality and reduced processing time.[6] Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), a three-dimensional extension, acquires multiple low-dose projections to reconstruct layered images, reducing tissue superimposition that can obscure lesions in two-dimensional (2D) imaging. Comparative studies demonstrate DBT yields higher invasive cancer detection rates (by 1-2 per 1000 screens) and lower recall rates for non-cancerous findings compared to 2D digital mammography alone.[39][40] Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses indicate mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality, with relative risk reductions ranging from 20% to 45% among adherent women aged 40-74, though absolute reductions are modest at 0.03-0.2% depending on age group. For instance, a 2024 cohort meta-analysis reported a 45% lower risk of breast cancer death in screened versus unscreened women, alongside reductions in all-cause mortality. Efficacy appears consistent across ages 40-49, challenging prior hesitancy for younger women due to denser breast tissue. However, trial results vary; some, like the Canadian National Breast Screening Study, found no significant mortality benefit, highlighting potential limitations in study design or adherence.[41][42][43] Major guidelines reflect this evidence but differ in recommendations. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) advises biennial screening for women aged 40-74 at average risk, updated in 2024 to include routine initiation at 40 rather than selective for 40-49. The American Cancer Society (ACS) endorses annual mammography starting at age 45 (with optional annual screening from 40-44) transitioning to biennial after 55, or continuing annually per preference. These protocols aim to balance benefits against harms, though critics argue annual screening from 40 maximizes mortality reduction based on trial data.[6][44][45] Harms include false-positive recalls prompting unnecessary biopsies (affecting 10-15% of screens cumulatively over a decade), psychological distress, and overdiagnosis of indolent lesions that would not progress clinically. Overdiagnosis rates vary by age and interval, estimated at 12-15% of detected cases in women aged 50-74 with biennial screening, rising to over 50% in those over 75 due to competing mortality risks. Radiation exposure from a standard two-view exam delivers approximately 3-4 mGy to the breast, equivalent to 4-6 weeks of background radiation, with modeled lifetime induced cancer risk from annual screening starting at 40 below 1 per 10,000 women—far outweighed by prevented deaths in empirical models. Dense breasts, present in about 40% of women under 50, reduce sensitivity to 70-80%, prompting supplemental ultrasound or MRI in select cases.[46][47][48]Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography, also known as breast ultrasound, employs high-frequency sound waves to image breast tissue, distinguishing fluid-filled cysts from solid masses and aiding in the evaluation of mammographic abnormalities.[49] In breast cancer screening, it serves primarily as an adjunct to mammography rather than a standalone modality, particularly for women with dense breasts where mammography sensitivity drops to 62-68%.[50] Handheld ultrasound requires skilled operators and is time-intensive, while automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) aims to standardize imaging but remains under evaluation for routine screening efficacy.[51] Observational studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that adding ultrasound to mammography increases cancer detection rates by 1.1 to 4.2 additional invasive cancers per 1,000 women screened, with higher yields in dense breasts (incremental detection rate of 3.5-4.3 per 1,000).[52][53] For instance, a 2023 meta-analysis of supplemental screening in dense breasts found ultrasound improved overall detection without evidence of stage shift benefits beyond mammography alone.[50] However, no randomized controlled trials have confirmed a reduction in breast cancer mortality from adjunct ultrasound, with ongoing studies like the Japanese J-START trial (initiated 2007, interim results 2021) showing only modest detection gains in women aged 40-49 without long-term survival data.[54] The modality's limitations include low specificity, leading to substantial harms: adjunct ultrasound yields 40-48 additional false-positive recalls per 1,000 screens and up to 14 unnecessary biopsies per 1,000, potentially causing patient anxiety, additional costs, and overdiagnosis of indolent lesions.[3][55] A 2024 systematic review for the USPSTF concluded insufficient evidence to assess the net balance of benefits and harms for supplemental ultrasound in average-risk women, citing the absence of mortality endpoints and reliance on surrogate outcomes like detection rates.[6] Guidelines vary: the American College of Radiology deems screening ultrasound usually appropriate as a supplement for women with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts at average risk (rating 6-7 on a 1-9 scale), but not for non-dense breasts.[56] In contrast, the USPSTF assigns an "I" statement (insufficient evidence) for supplemental screening modalities like ultrasound, prioritizing mammography alone for average-risk populations.[44] For high-risk women, ultrasound may complement MRI, though evidence remains observational and operator-dependent factors limit reproducibility.[57] Emerging automated systems show promise in reducing variability, with one 2023 meta-analysis reporting sensitivity improvements to 81% when added to mammography, but prospective trials are needed to validate mortality impacts.[51]Molecular Breast Imaging

Molecular breast imaging (MBI), also known as breast-specific gamma imaging, is a functional imaging modality that employs a radioactive tracer to identify metabolically active breast tissue, thereby detecting malignancies based on increased uptake in cancerous cells rather than anatomical structure. The procedure involves intravenous injection of technetium-99m sestamibi, a lipophilic agent that accumulates preferentially in tumor cells due to their higher mitochondrial activity and blood flow, followed by imaging using dedicated gamma cameras positioned against the breasts with mild compression similar to mammography.[58][59] Developed in the early 2000s at the Mayo Clinic, MBI targets limitations of mammography in women with dense breast tissue, where parenchymal density obscures non-calcified lesions, reducing mammographic sensitivity to approximately 62-68% compared to over 90% in fatty breasts.[60][61] In supplemental screening contexts, MBI demonstrates high sensitivity for invasive ductal carcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ, and invasive lobular carcinoma, with detection rates increasing from 3 cancers per 1,000 screenings with mammography alone to 12 per 1,000 when combined with MBI in women with dense breasts.[58] A retrospective analysis of over 1,500 women with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts found MBI added detection of 7.2 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened, primarily small invasive tumors less than 1 cm, with a positive predictive value of 25% for biopsies prompted by MBI findings.[62] Unlike ultrasound, which excels at cyst characterization but has lower specificity leading to higher false positives, MBI's specificity approaches 90% in dense breast cohorts, minimizing unnecessary recalls while identifying cancers missed by mammography in up to 50% of cases.[60] Recent advancements, including cadmium-zinc-telluride detectors, enable lower-dose protocols that maintain diagnostic accuracy.[59] Radiation exposure from low-dose MBI protocols yields an effective whole-body dose of 1.8-2.4 mSv, higher than the 0.4-0.5 mSv from two-view digital mammography but with a more favorable breast-specific dose due to targeted tracer uptake; comparative risk models estimate MBI's benefit-to-radiation-induced cancer risk ratio at 5-9 for supplemental screening in dense breasts, versus variable ratios for mammography depending on age and frequency.[63][64] Although whole-body exposure raises theoretical stochastic risks, empirical data from nuclear medicine applications indicate no excess cancers attributable to such doses in screened populations, and MBI's ability to detect early-stage disease offsets potential harms through stage shift.[65] While prospective trials like the Density MATTERS study (initiated 2017, targeting 3,000 women with dense breasts) compare MBI plus digital breast tomosynthesis to tomosynthesis alone for detection and interval cancer rates, no large-scale randomized controlled trials have yet demonstrated direct breast cancer mortality reduction from MBI supplementation.[66] Current evidence supports its use as an adjunct in high-risk or dense-breast subsets, with Mayo Clinic data from 2025 showing combined MBI and 3D mammography yielding 50% fewer missed cancers than mammography alone, though broader adoption is limited by availability, cost, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's 2024 assessment of insufficient evidence for routine supplemental screening modalities due to gaps in long-term outcome data.[67][6] Biopsy rates rise modestly by 2-3% with MBI addition, lower than ultrasound's 8%, but overdiagnosis concerns persist absent mortality endpoints.[68]Supplemental and Advanced Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast, often performed with contrast enhancement, serves as a supplemental screening tool primarily for women at elevated risk of breast cancer, such as those with lifetime risk exceeding 20% due to genetic mutations like BRCA1/2 or strong family history.[69] Unlike mammography, which relies on X-ray imaging, breast MRI uses magnetic fields and gadolinium-based contrast to highlight areas of abnormal vascularity indicative of malignancy, offering higher sensitivity for detecting invasive cancers, particularly in dense breast tissue where mammography performance diminishes.[70] In high-risk cohorts, MRI combined with mammography achieves cancer detection rates of up to 14.7 per 1,000 screenings, compared to 7.8 per 1,000 with mammography alone, with MRI identifying additional cancers missed by mammography in 71% of cases versus 25% for mammography in pivotal trials.[71] Evidence from prospective studies supports MRI's role in enhancing early detection among high-risk women, though randomized controlled trials demonstrating mortality reduction remain limited. A pooled analysis of screening programs reported that supplemental MRI increased sensitivity to 94.1% from 68.1% with mammography alone, while maintaining comparable specificity after initial rounds.[72] Observational data from BRCA1 mutation carriers indicate that MRI surveillance correlates with a 48% reduction in breast cancer mortality risk compared to mammography alone, attributed to earlier stage detection (predominantly stage I or lower).[73] In women with extremely dense breasts, the DENSE trial demonstrated that supplemental MRI reduced interval cancers by over 80% relative to mammography, diagnosing 4.2 additional invasive cancers per 1,000 women screened without immediate mortality endpoints.[74] However, for average-risk women or those with dense breasts alone, major guidelines like those from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force deem evidence insufficient to assess net benefits, citing a lack of long-term randomized data on survival outcomes.[6] Despite its detection advantages, breast MRI is associated with substantial harms, including high false-positive rates that drive unnecessary interventions. False-positive recall rates range from 7.5% to 12.1% per screening round, exceeding mammography's 4-10%, leading to additional biopsies (up to 15% of exams) and psychological distress from diagnostic uncertainty.[75] These cascades often result in benign findings prompting short-interval follow-up or procedures, with one study estimating that for every true cancer detected, 2-3 false positives occur, amplifying healthcare costs—estimated at 2,000 per exam—and potential overtreatment of indolent lesions without proven mortality benefit in population-level screening.[76] Specificity improves to 88-97% in subsequent rounds as baseline abnormalities resolve, but initial overuse remains a barrier to broader adoption.[77] Professional societies, including the American College of Radiology, endorse annual MRI from ages 25-30 for high-risk groups but caution against routine use in lower-risk populations due to these trade-offs.[69]Contrast-Enhanced Mammography

Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM), also known as contrast-enhanced digital mammography, is a supplemental imaging technique that combines standard mammography with the intravenous administration of an iodinated contrast agent to detect breast lesions based on neoangiogenesis.[78] The procedure involves acquiring low-energy (LE) and high-energy (HE) images post-contrast injection, followed by digital subtraction to isolate enhancing areas, which highlight tumors due to their increased vascularity compared to normal tissue.[79] CEM is typically performed after standard mammography or tomosynthesis, targeting women with dense breasts or elevated risk where conventional screening sensitivity is limited.[80] Clinical studies demonstrate CEM's superior cancer detection rates over standard mammography alone. In a prospective supplemental screening trial for elevated-risk women, CEM yielded an incremental detection rate of 23.9 cancers per 1,000 screens, primarily early-stage invasive cancers.[81] A ten-year screening evaluation in intermediate- and high-risk populations reported a overall cancer detection rate of 13.1 per 1,000 examinations, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.923 indicating strong diagnostic accuracy.[82] Sensitivity for invasive cancers reaches 98% in some cohorts, outperforming digital mammography's 60-90% range, particularly in dense breasts where standard imaging misses up to 50% of cancers.[83] [84] In women with extremely dense breasts, CEM improves sensitivity over LE mammography (e.g., from 52.4% to 90.5%) but may reduce specificity, leading to more recalls, though specificity rises with radiologist experience.[80] [85] Compared to breast MRI, CEM shows comparable overall sensitivity (97% vs. 96%) in lesion detection but lower performance in some high-risk settings, with a sensitivity difference of -38.9% and detection rate gap of -14.2 per 1,000 versus standard MRI.[86] [87] Against automated breast ultrasound (ABUS), CEM detects three times more invasive cancers, with smaller tumor sizes, positioning it as a viable alternative for supplemental screening where MRI access or tolerability is limited.[57] Limitations include potential overdiagnosis from enhanced visibility of benign lesions, increased false positives (specificity 50-89%), and risks associated with iodinated contrast such as allergic reactions (0.3-1%) or contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with renal impairment.[88] [89] Radiation dose remains similar to standard mammography, but cumulative exposure warrants consideration in frequent screening.[78] Long-term mortality reduction data are pending larger randomized trials, as current evidence focuses on detection metrics rather than survival outcomes.[79] CEM's role is thus emerging in risk-stratified protocols, offering a cost-effective, accessible option over MRI without requiring specialized equipment beyond contrast-capable mammography units.[90]Risk-Stratified Approaches

Genetic Testing and High-Risk Identification

Genetic testing identifies individuals at substantially elevated lifetime risk of breast cancer due to germline pathogenic variants in susceptibility genes, enabling risk-stratified screening protocols that commence earlier and incorporate supplemental modalities. Pathogenic variants in genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with the highest risks, with women carrying BRCA1 variants facing a 55-72% lifetime risk of breast cancer and those with BRCA2 variants a 45-69% risk, compared to approximately 12-13% in the general population.[91][92] Other moderate-penetrance genes like PALB2 confer risks up to 35-60% by age 70-80, particularly with family history, while high-penetrance genes such as TP53 (Li-Fraumeni syndrome) can exceed 90% lifetime risk.[93][94] These variants account for 5-10% of breast cancers overall, with higher prevalence in families with multiple cases or early-onset disease.[95] Testing typically involves multigene panel sequencing rather than single-gene analysis, assessing dozens of genes for pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, variants of uncertain significance, or benign polymorphisms. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends risk assessment using tools like the Ontario Family History Assessment Tool or Manchester Scoring System for women with personal or family histories suggestive of hereditary risk, followed by genetic counseling and testing if criteria are met; routine screening is not advised for those without such indicators.[96] National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines expand criteria to include personal history of triple-negative breast cancer under age 60, male breast cancer, or Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry with minimal family history, reflecting updated evidence that broader testing identifies actionable risks without requiring strict familial thresholds.[97][98] Prevalence of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants is about 1 in 300-400 in unselected populations but rises to 2-3% among women with breast cancer and 10% or more in those with ovarian cancer or strong family histories.[91] For individuals testing positive, high-risk status—often defined as lifetime risk exceeding 20%—triggers intensified surveillance to achieve earlier detection and stage shift. NCCN and American College of Radiology guidelines recommend annual mammography combined with contrast-enhanced breast MRI starting at age 25-30 for BRCA1/2 carriers (or 8 years before the earliest family diagnosis, if later), continuing through at least age 75 or beyond based on health status, as MRI detects 70-90% of cancers missed by mammography alone in dense breasts common in younger high-risk women.[97][99] For those unable to undergo MRI, alternatives like contrast-enhanced mammography may be considered, though evidence supports MRI's superior sensitivity (71-94%) over mammography (23-40%) in this cohort.[99][100] This approach reduces interval cancers by up to 50% in trials of high-risk women, though it increases false positives and requires counseling on psychological impacts and potential overdiagnosis.[101][102]Personalized Screening Protocols

Personalized screening protocols for breast cancer adjust the timing, frequency, and modalities of screening based on an individual's estimated risk, aiming to optimize detection while minimizing harms such as overdiagnosis. Risk assessment typically involves validated models like the Gail model for primarily mammographic risk factors or the Tyrer-Cuzick (IBIS) model incorporating family history, genetics, and breast density to calculate lifetime or 10-year risk.[103] [104] Women with a lifetime risk below 15-20% follow average-risk guidelines, such as biennial mammography from ages 40-74, whereas those exceeding this threshold receive intensified protocols.[6] [105] For high-risk individuals, including carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations or those with lifetime risks over 20%, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends initiating annual screening with both mammography and contrast-enhanced breast MRI as early as age 25, continuing through at least age 75 or as long as life expectancy supports benefit.[106] [105] The American Cancer Society (ACS) endorses similar annual mammogram-plus-MRI starting at age 30 for lifetime risks of 20-25% or greater, with earlier initiation for genetic syndromes like Li-Fraumeni.[107] [102] Breast density plays a key role; women with extremely dense breasts (BI-RADS category D) and elevated risk may require supplemental ultrasound or abbreviated MRI protocols to address mammography's reduced sensitivity in dense tissue.[108] [69] Implementation involves initial risk evaluation starting at age 25 via clinical history, genetic testing if indicated, and imaging for density assessment.[105] For moderate-risk women (e.g., 10-year risk >5% but <20% lifetime), protocols may include annual mammography with optional tomosynthesis or shorter intervals rather than biennial standard.[109] Emerging evidence from feasibility studies supports the practicality of such stratification in general populations, with models demonstrating improved prediction accuracy when integrating polygenic risk scores alongside traditional factors.[110] [103] Ongoing trials, such as the Personalized Risk-based Breast Cancer Screening (PRO-BE) or DENSE studies, evaluate outcomes like stage-shift and cost-effectiveness, showing potential reductions in interval cancers for high-risk groups without proportional harm increases in low-risk ones.[111] [112] However, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force notes insufficient direct evidence from randomized trials to fully endorse broad risk-stratified approaches beyond high-risk subsets, highlighting needs for further validation to avoid unintended disparities in access or false reassurance.[6] [3]Benefits

Reduction in Advanced-Stage Diagnoses