Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Loris

View on Wikipedia

| Lorises Temporal range: Miocene to present

| |

|---|---|

| |

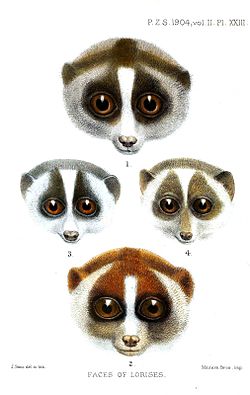

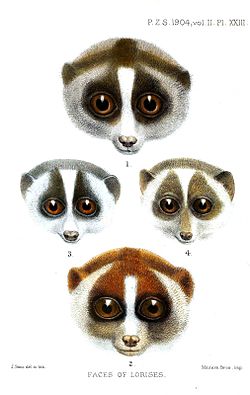

| Joseph Smit's Faces of Lorises (1904) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Lorisidae |

| Subfamily: | Lorinae Gray, 1821[1] |

| Genera | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Loris is the common name for the wet-nosed primates of the subfamily Lorinae[1] (sometimes spelled Lorisinae[2]) in the family Lorisidae. Loris is one genus in this subfamily and includes the slender lorises, Nycticebus is the genus containing the slow lorises, and Xanthonycticebus is the genus name of the pygmy slow loris.

Description

[edit]Lorises are nocturnal and arboreal.[3] They are found in tropical and woodland forests of India, Sri Lanka, and parts of southeast Asia. They resemble lemurs.[4] A loris's locomotion is a slow and cautious climbing form of quadrupedalism. Some lorises are almost entirely insectivorous, while others also include fruits, gums, leaves, and slugs in their diet.[4]

Lorises are strepsirrhines, most of which have a toothcomb, a special adaptation in their lower front teeth. This toothcomb is used for grooming their fur and even injecting their venom.[5]

Female lorises practice infant parking, leaving their infants in trees or bushes. Before they do this, they bathe their young with allergenic saliva that is acquired by licking patches on the insides of their elbows which produce a mild toxin that discourages most predators,[4] though orangutans occasionally eat lorises.[6]

Taxonomic classification

[edit]The family Lorisidae is found within the infraorder Lemuriformes and superfamily Lorisoidea, along with the family Galagidae, the galagos. This superfamily is a sister taxon of Lemuroidea, the lemurs. Within Lorinae, there are ten species (and several more subspecies) of lorises across three genera:[1]

- Family Lorisidae

- Subfamily Perodicticinae

- Subfamily Lorinae

- Genus Loris

- Gray slender loris, Loris lydekkerianus

- Highland slender loris, L. lydekkerianus grandis

- Mysore slender loris, L. lydekkerianus lydekkerianus

- Malabar slender loris, L. lydekkerianus malabaricus

- Northern Ceylonese slender loris, L. lydekkerianus nordicus

- Red slender loris, L. tardigradus

- Dry Zone slender loris, L. tardigradus tardigradus

- Horton Plains slender loris, L. tardigradus nyctoceboides

- Gray slender loris, Loris lydekkerianus

- Genus Xanthonycticebus[7]

- Pygmy slow loris, X. pygmaeus

- Genus Nycticebus

- Bangka slow loris, Nycticebus bancanus

- Bengal slow loris, N. bengalensis

- Bornean slow loris, N. borneanus

- Sunda slow loris, N. coucang

- Javan slow loris, N. javanicus

- Kayan River slow loris, N. kayan

- Philippine slow loris, N. menagensis

- Sumatran slow loris, N. hilleri

- †? N. linglom (fossil, Miocene)

- Genus Loris

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Brandon-Jones, D.; Eudey, A. A.; Geissmann, T.; Groves, C. P.; Melnick, D. J.; Morales, J. C.; Shekelle, M.; Stewart, C.-B. (2004). "Asian Primate Classification" (PDF). International Journal of Primatology. 25 (1): 100. doi:10.1023/b:ijop.0000014647.18720.32. S2CID 29045930.

- ^ Nowak, Ronald M.; Pillsbury Walker, Ernest (28 October 1999). Walker's Primates of the World. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6251-9.

loris OR lorises.

- ^ a b c Jurmain, Robert; Kilgore, Lynn; et al. (2008). Introduction to Physical Anthropology. p. 211. ISBN 978-1337099820.

- ^ Nekaris, K A I (2014). "Extreme primates: Ecology and evolution of Asian lorises". Evol Anthropol. 23 (5): 177–87. doi:10.1002/evan.21425. PMID 25347976. S2CID 1948088.

- ^ "Orangutan Ecology". Orangutan Foundation International. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- ^ Nekaris, K. Anne-Isola; Nijman, Vincent (2022-03-23). "A new genus name for pygmy lorises, Xanthonycticebus gen. nov. (Mammalia, primates)". Zoosystematics and Evolution. 98 (1): 87–92. doi:10.3897/zse.98.81942. ISSN 1860-0743. S2CID 247649999.

External links

[edit]![]() Data related to Loris at Wikispecies

Data related to Loris at Wikispecies