Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bronchiole

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2015) |

| Bronchiole | |

|---|---|

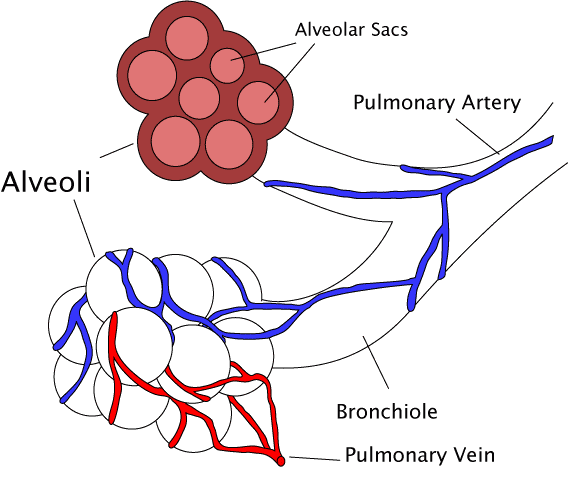

Diagram of the alveoli with both cross-section and external view. | |

| Details | |

| System | Respiratory system |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D055745 |

| TA98 | A06.5.02.026 |

| TA2 | 3282 |

| TH | H3.05.02.0.00005 |

| FMA | 7410 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The bronchioles (/ˈbrɑːŋkioʊls/ BRONG-kee-ohls) are the smaller branches of the bronchial airways in the lower respiratory tract. They include the terminal bronchioles, and finally the respiratory bronchioles that mark the start of the respiratory zone delivering air to the gas exchanging units of the alveoli. The bronchioles no longer contain the cartilage that is found in the bronchi, or glands in their submucosa.[1]

Structure

[edit]

The pulmonary lobule is the portion of the lung ventilated by one bronchiole. Bronchioles are approximately 1 mm or less in diameter and their walls consist of ciliated cuboidal epithelium and a layer of smooth muscle. Bronchioles divide into even smaller bronchioles, called terminal, which are 0.5 mm or less in diameter. Terminal bronchioles in turn divide into smaller respiratory bronchioles which divide into alveolar ducts. Terminal bronchioles mark the end of the conducting division of air flow in the respiratory system while respiratory bronchioles are the beginning of the respiratory division where gas exchange takes place.

The diameter of the bronchioles plays an important role in air flow. The bronchioles change diameter to either increase or reduce air flow. An increase in diameter is called bronchodilation and is stimulated by either epinephrine or sympathetic nerves to increase air flow. A decrease in diameter is called bronchoconstriction, which is the tightening of the smooth muscle surrounding the bronchi and bronchioles due to and stimulated by histamine, parasympathetic nerves, cold air, chemical irritants, excess mucus production, viral infections, and other factors to decrease air flow. Bronchoconstriction can result in clinical symptoms such as wheezing, chest tightness, and dyspnea, which are common features of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and chronic bronchitis. [2]

Bronchioles

[edit]

The trachea divides into the left main bronchus which supplies the left lung, and the right main bronchus which supplies the right lung. As they enter the lungs these primary bronchi branch into secondary bronchi known as lobar bronchi which supply each lobe of the lung. These in turn give rise to tertiary bronchi (tertiary meaning "third"), known as segmental bronchi which supply each bronchopulmonary segment.[1] The segmentary bronchi subdivide into fourth order, fifth order and sixth order segmental bronchi before dividing into the bronchioles. The bronchioles are histologically distinct from the bronchi in that their walls do not have hyaline cartilage and they have club cells in their epithelial lining. The epithelium of the bronchioles starts as a simple ciliated columnar epithelium and changes to simple ciliated cuboidal epithelium as the bronchioles decreases in size. The diameter of the bronchioles is often said to be less than 1 mm, though this value can range from 5 mm to 0.3 mm. As stated, these bronchioles do not have hyaline cartilage to maintain their patency. Instead, they rely on elastic fibers attached to the surrounding lung tissue for support. The inner lining (lamina propria) of these bronchioles is thin with no glands present, and is surrounded by a layer of smooth muscle. As the bronchioles get smaller they divide into terminal bronchioles. Each bronchiole divides into between 50 and 80 terminal bronchioles.[3] These bronchioles mark the end of the conducting zone, which covers the first division through the sixteenth division of the respiratory tract. Alveoli only become present when the conducting zone changes to the respiratory zone, from the sixteenth through the twenty-third division of the tract.

Terminal bronchioles

[edit]The terminal bronchioles are the most distal segment of the conducting zone. They branch off the lesser bronchioles. Each of the terminal bronchioles divides to form respiratory bronchioles which contain a small number of alveoli. Terminal bronchioles are lined with simple ciliated cuboidal epithelium containing club cells. Club cells are non-ciliated, rounded protein-secreting cells. Their secretions are a non-sticky, proteinaceous compound to maintain the airway in the smallest bronchioles. The secretion, called pulmonary surfactant, reduces surface tension, allowing for bronchioles to expand during inspiration and keeping the bronchioles from collapsing during expiration. Club cells are a stem cell of the respiratory system, and also produce enzymes that detoxify substances dissolved in the respiratory fluid.

Respiratory bronchioles

[edit]The respiratory bronchioles are the narrowest airways of the lungs, 0.5 mm across.[4] The bronchi divide many times before evolving into the bronchioles. The respiratory bronchioles deliver air to the exchange surfaces of the lungs.[5] They are interrupted by alveoli which are thin walled evaginations. Alveolar ducts are side branches of the respiratory bronchioles. The respiratory bronchioles are lined by ciliated cuboidal epithelium along with some non-ciliated cells called club cells.[6]

Clinical significance

[edit]Bronchospasm, a potentially life-threatening situation, occurs when the smooth muscular tissue of the bronchioles constricts, severely narrowing their diameter. The most common cause of this is asthma. Bronchospasm is commonly treated by oxygen therapy and bronchodilators such as albuterol.

Diseases of the bronchioles include asthma, bronchiolitis obliterans, respiratory syncytial virus infections, and influenza.

Inflammation

[edit]The medical condition of inflammation of the bronchioles is termed bronchiolitis.[7]

Additional images

[edit]-

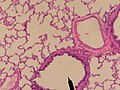

Cross sectional cut of primary bronchiole

-

- Trachea

- Primary bronchus

- Lobar bronchus

- Segmental bronchus

- Bronchiole

- Alveolar duct

- Alveolus

References

[edit]- ^ a b Tortora GJ (2010). Principles of anatomy and physiology (12th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 883–888. ISBN 9780470233474.

- ^ Bacsi A, Pan L, Ba X, Boldogh I (February 2016). "Pathophysiology of bronchoconstriction: role of oxidatively damaged DNA repair". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 16 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000232. PMC 4940044. PMID 26694039.

- ^ Saladin K (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 640–641. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ Merck Manual of Medical Information (Home ed.). Whitehouse Station, N.J.: Merck Research Laboratories. 1997. ISBN 978-0-911910-87-2.

- ^ Martini FH, Timmons MJ, Tallitsch RB. Human Anatomy (6th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. p. 643. ISBN 978-0-321-49804-5.

- ^ Paxton, Steve; Peckham, Michelle; Knibbs, Adele (2003). "Respiratory: Trachea, bronchioles and bronchi". University of Leeds.

- ^ Friedman JN, Rieder MJ, Walton JM (November 2014). "Bronchiolitis: Recommendations for diagnosis, monitoring and management of children one to 24 months of age". Paediatrics & Child Health. 19 (9): 485–498. doi:10.1093/pch/19.9.485. PMC 4235450. PMID 25414585.

Further reading

[edit]- Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology: the Unity of Form and Function. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2007.

- Dudek, Ronald W. High-Yield Histology, 3rd ed. (2004). ISBN 0-7817-4763-5

- Gartner, Leslie P. and James L. Hiatt. Color Atlas of Histology, 3rd ed. (2000). ISBN 0-7817-3509-2

- Gartner, Leslie P. and James L. Hiatt. Color Textbook of Histology (2001). ISBN 0-7216-8806-3

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 13606loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Histology image: 13607loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Diagram at davidson.edu

- Histology at umdnj.edu