Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bronchus

View on Wikipedia| Bronchus | |

|---|---|

The bronchi are conducting passages for air into the lungs. | |

The bronchi form part of the lower respiratory tract | |

| Details | |

| System | Respiratory system |

| Artery | Bronchial artery |

| Vein | Bronchial vein |

| Nerve | Pulmonary branches of vagus nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | bronchus |

| Greek | βρόγχος |

| MeSH | D001980 |

| TA98 | A06.4.01.001 A06.3.01.008 |

| TA2 | 3226 |

| FMA | 7409 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

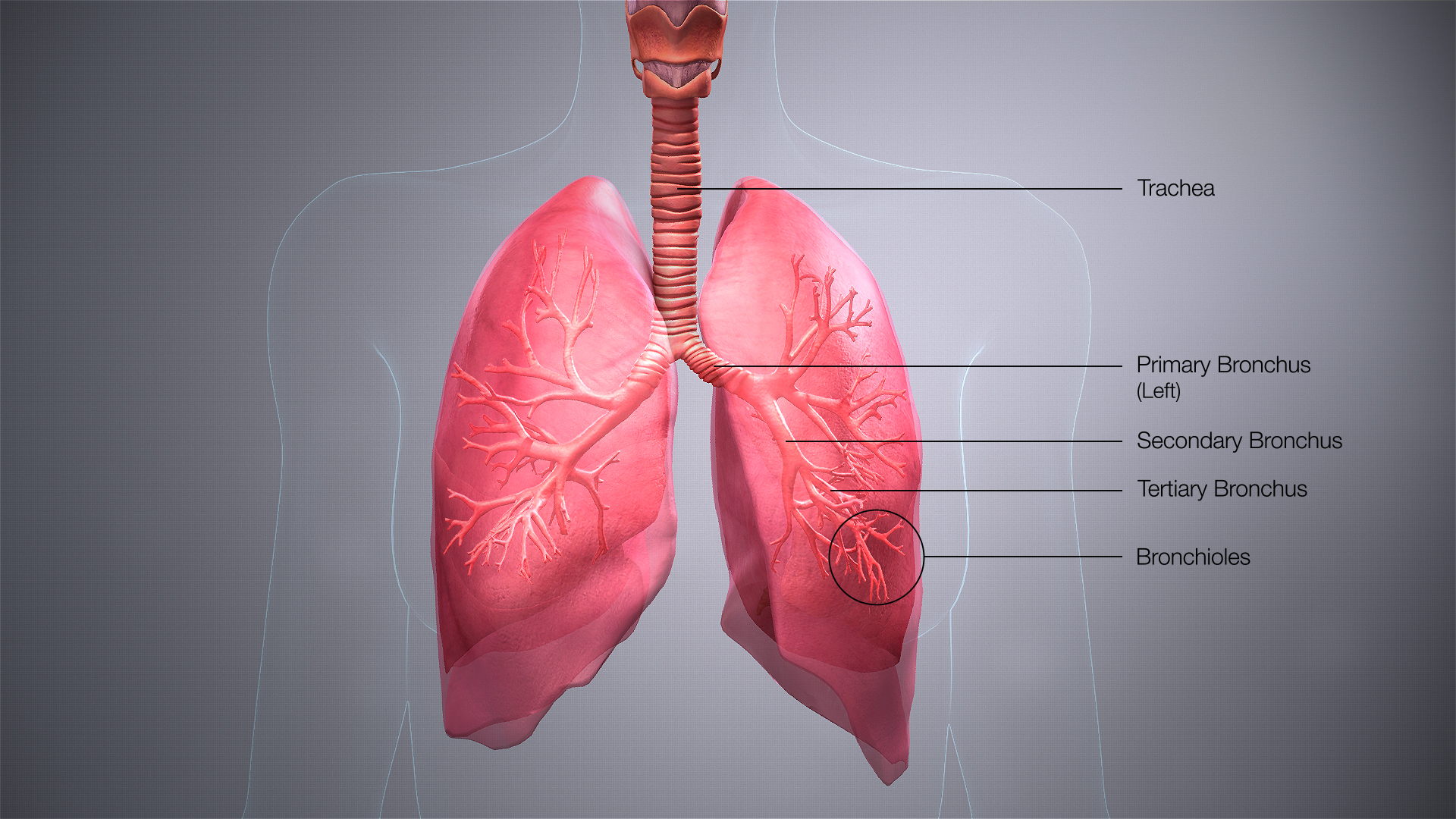

A bronchus (/ˈbrɒŋkəs/ BRONG-kəs; pl.: bronchi, /ˈbrɒŋkaɪ/ BRONG-ky) is a passage or airway in the lower respiratory tract that conducts air into the lungs. The first or primary bronchi to branch from the trachea at the carina are the right main bronchus and the left main bronchus. These are the widest bronchi, and enter the right lung, and the left lung at each hilum. The main bronchi branch into narrower secondary bronchi or lobar bronchi, and these branch into narrower tertiary bronchi or segmental bronchi. Further divisions of the segmental bronchi are known as 4th order, 5th order, and 6th order segmental bronchi, or grouped together as subsegmental bronchi.[1][2] The bronchi, when too narrow to be supported by cartilage, are known as bronchioles. No gas exchange takes place in the bronchi.

Structure

[edit]The trachea (windpipe) divides at the carina into two main or primary bronchi, the left bronchus and the right bronchus. The carina of the trachea is located at the level of the sternal angle and the fifth thoracic vertebra (at rest).

The right main bronchus is wider, shorter, and more vertical than the left main bronchus,[3] its mean length is 1.09 cm.[4] It enters the root of the right lung at approximately the fifth thoracic vertebra. The right main bronchus subdivides into three secondary bronchi (also known as lobar bronchi), which deliver oxygen to the three lobes of the right lung—the superior, middle and inferior lobe. The azygos vein arches over it from behind; and the right pulmonary artery lies at first below and then in front of it. About 2 cm from its commencement it gives off a branch to the superior lobe of the right lung, which is also called the eparterial bronchus. Eparterial refers to its position above the right pulmonary artery. The right bronchus now passes below the artery, and is known as the hyparterial branch which divides into the two lobar bronchi to the middle and lower lobes.

The left main bronchus is smaller in caliber but longer than the right, being 5 cm long. It enters the root of the left lung opposite the sixth thoracic vertebra. It passes beneath the aortic arch, crosses in front of the esophagus, the thoracic duct, and the descending aorta, and has the left pulmonary artery lying at first above, and then in front of it. The left bronchus has no eparterial branch, and therefore it has been supposed by some that there is no upper lobe to the left lung, but that the so-called upper lobe corresponds to the middle lobe of the right lung. The left main bronchus divides into two secondary bronchi or lobar bronchi, to deliver air to the two lobes of the left lung—the superior and the inferior lobe.

The secondary bronchi divide further into tertiary bronchi, (also known as segmental bronchi), each of which supplies a bronchopulmonary segment. A bronchopulmonary segment is a division of a lung separated from the rest of the lung by a septum of connective tissue. This property allows a bronchopulmonary segment to be surgically removed without affecting other segments. Initially, there are ten segments in each lung, but during development with the left lung having just two lobes, two pairs of segments fuse to give eight, four for each lobe. The tertiary bronchi divide further in another three branchings known as 4th order, 5th order and 6th order segmental bronchi which are also referred to as subsegmental bronchi. These branch into many smaller bronchioles which divide into terminal bronchioles, each of which then gives rise to several respiratory bronchioles, which go on to divide into two to eleven alveolar ducts. There are five or six alveolar sacs associated with each alveolar duct. The alveolus is the basic anatomical unit of gas exchange in the lung.

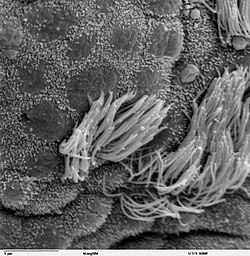

The main bronchi have relatively large lumens that are lined by respiratory epithelium. This cellular lining has cilia departing towards the mouth which removes dust and other small particles. There is a smooth muscle layer below the epithelium arranged as two ribbons of muscle that spiral in opposite directions. This smooth muscle layer contains seromucous glands, which secrete mucus, in its wall. Hyaline cartilage is present in the bronchi, surrounding the smooth muscle layer. In the main bronchi, the cartilage forms C-shaped rings like those in the trachea, while in the smaller bronchi, hyaline cartilage is present in irregularly arranged crescent-shaped plates and islands. These plates give structural support to the bronchi and keep the airway open.[5]

The bronchial wall normally has a thickness of 10% to 20% of the total bronchial diameter.[6]

Microanatomy

[edit]

The cartilage and mucous membrane of the main bronchus (primary bronchi) are similar to those in the trachea. They are lined with respiratory epithelium, which is classified as ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium.[7] The epithelium in the main bronchi contains goblet cells, which are glandular, modified simple columnar epithelial cells that produce mucins, the main component of mucus. Mucus plays an important role in keeping the airways clear in the mucociliary clearance process.

As branching continues through the bronchial tree, the amount of hyaline cartilage in the walls decreases until it is absent in the bronchioles. As the cartilage decreases, the amount of smooth muscle increases. The mucous membrane also undergoes a transition from ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium, to simple ciliated cuboidal epithelium, to simple squamous epithelium in the alveolar ducts and alveoli[7][8]

Variation

[edit]In 0.1 to 5% of people there is a right superior lobe bronchus arising from the main stem bronchus prior to the carina. This is known as a tracheal bronchus, and seen as an anatomical variation.[9] It can have multiple variations and, although usually asymptomatic, it can be the root cause of pulmonary disease such as a recurrent infection. In such cases resection is often curative.[10] [11]

The cardiac bronchus has a prevalence of ≈0.3% and presents as an accessory bronchus arising from the bronchus intermedius between the upper lobar bronchus and the origin of the middle and lower lobar bronchi of the right main bronchus.[12]

An accessory cardiac bronchus is usually an asymptomatic condition but may be associated with persistent infection or hemoptysis.[13][14] In about half of observed cases the cardiac bronchus presents as a short dead-ending bronchial stump, in the remainder the bronchus may exhibit branching and associated aerated lung parenchyma.

Function

[edit]The bronchi function to carry air that is breathed in through to the functional tissues of the lungs, called alveoli. Exchange of gases between the air in the lungs and the blood in the capillaries occurs across the walls of the alveolar ducts and alveoli. The alveolar ducts and alveoli consist primarily of simple squamous epithelium, which permits rapid diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Clinical significance

[edit]

Bronchial wall thickening, as can be seen on CT scan, generally (but not always) implies inflammation of the bronchi (bronchitis).[15] Normally, the ratio of the bronchial wall thickness and the bronchial diameter is between 0.17 and 0.23.[16]

Bronchitis

[edit]Bronchitis is defined as inflammation of the bronchi, which can either be acute or chronic. Acute bronchitis is usually caused by viral or bacterial infections. Many sufferers of chronic bronchitis also suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and this is usually associated with smoking or long-term exposure to irritants.

Aspiration

[edit]The left main bronchus departs from the trachea at a greater angle than that of the right main bronchus. The right bronchus is also wider than the left and these differences predispose the right lung to aspirational problems. If food, liquids, or foreign bodies are aspirated, they will tend to lodge in the right main bronchus. Bacterial pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia may result.

If a tracheal tube used for intubation is inserted too far, it will usually lodge in the right bronchus, allowing ventilation only of the right lung.

Asthma

[edit]Asthma is marked by hyperresponsiveness of the bronchi with an inflammatory component, often in response to allergens.

In asthma, the constriction of the bronchi can result in difficulty in breathing giving shortness of breath; this can lead to a lack of oxygen reaching the body for cellular processes. In this case, an inhaler can be used to rectify the problem. The inhaler administers a bronchodilator, which serves to soothe the constricted bronchi and to re-expand the airways. This effect occurs quite quickly.

Bronchial atresia

[edit]Bronchial atresia is a rare congenital disorder that can have a varied appearance. A bronchial atresia is a defect in the development of the bronchi, affecting one or more bronchi – usually segmental bronchi and sometimes lobar. The defect takes the form of a blind-ended bronchus. The surrounding tissue secretes mucus normally but builds up and becomes distended.[17] This can lead to regional emphysema.[18]

The collected mucus may form a mucoid impaction or a bronchocele, or both. A pectus excavatum may accompany a bronchial atresia.[17]

Additional images

[edit]-

Cross-section of secondary bronchus

-

The left and right main bronchi sit behind the heart, shown here.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Netter, Frank H. (2014). Atlas of Human Anatomy Including Student Consult Interactive Ancillaries and Guides (6th ed.). Philadelphia, Penn.: W B Saunders Co. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-4557-0418-7.

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. wood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.[page needed]

- ^ Brodsky, JB; Lemmens, JM (2003). "Left Double-Lumen Tubes: Clinical Experience With 1,170 Patients" (PDF). Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 17 (3): 289–98. doi:10.1016/S1053-0770(03)00046-6. PMID 12827573. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-12. Alt URL

- ^ Robinson, CL; Müller, NL; Essery, C (January 1989). "Clinical significance and measurement of the length of the right main bronchus". Canadian Journal of Surgery. 32 (1): 27–8. PMID 2642720.

- ^ Saladin, K (2012). Anatomy & physiology : the unity of form and function (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 862. ISBN 9780073378251.

- ^ Section SA6-PA4 ("Airway Inflammation with Wall Thickening") in: Brett M. Elicker, W. Richard Webb (2012). Fundamentals of High-Resolution Lung CT: Common Findings, Common Patterns, Common Diseases, and Differential Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781469824796.

- ^ a b Marieb, Elaine N.; Hoehn, Katja (2012). Human Anatomy & Physiology (9th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0321852120.

- ^ "Bronchi, Bronchial Tree & Lungs". nih.gov. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ Weerakkody, Yuranga. "Tracheal bronchus | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Shih, Fu-Chieh; Wei-Jing Lee; Hung-Jung Lin (2009-03-31). "Tracheal bronchus". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 180 (7): 783. doi:10.1503/cmaj.080280. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 2659830. PMID 19332762.

- ^ Barat, Michael; Horst R. Konrad (1987-03-04). "Tracheal bronchus". American Journal of Otolaryngology. 8 (2): 118–122. doi:10.1016/S0196-0709(87)80034-0. ISSN 0196-0709. PMID 3592078.

- ^ "Cardiac bronchus". Radiopedia. Archived from the original on 2015-11-15.

- ^ Parker MS, Christenson ML, Abbott GF. Teaching atlas of chest imaging. 2006, ISBN 3131390212

- ^ McGuinness G, Naidich DP, Garay SM, Davis AL, Boyd AD, Mizrachi HH (1993). "Accessory cardiac bronchus: CT features and clinical significance". Radiology. 189 (2): 563–6. doi:10.1148/radiology.189.2.8210391. PMID 8210391.

- ^ Weerakkody, Yuranga (2021-01-13). "Bronchial wall thickening". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- ^ Page 112 in: David P. Naidich (2005). Imaging of the Airways: Functional and Radiologic Correlations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781757683.

- ^ a b Traibi, A.; Seguin-Givelet, A.; Grigoroiu, M.; Brian, E.; Gossot, D. (2017). "Congenital bronchial atresia in adults: Thoracoscopic resection". Journal of Visualized Surgery. 3: 174. doi:10.21037/jovs.2017.10.15. PMC 5730535. PMID 29302450.

- ^ Van Klaveren, R. J.; Morshuis, W. J.; Lacquet, L. K.; Cox, A. L.; Festen, J.; Heystraten, F. M. (1992). "Congenital bronchial atresia with regional emphysema associated with pectus excavatum". Thorax. 47 (12): 1082–3. doi:10.1136/thx.47.12.1082. PMC 1021111. PMID 1494776.

Sources

[edit]- Moore, Keith L. and Arthur F. Dalley. Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 4th ed. (1999). ISBN 0-7817-5936-6.