Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

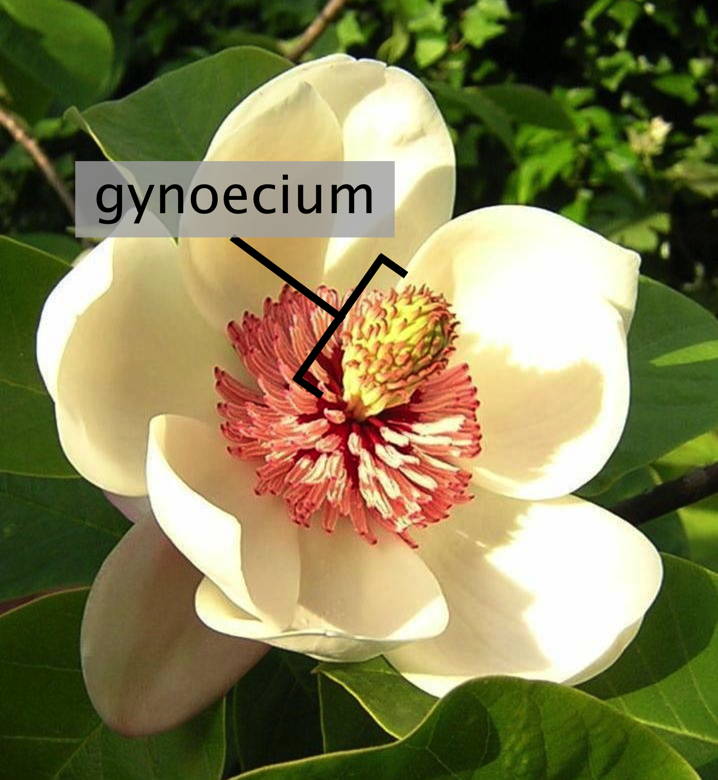

Gynoecium

View on Wikipedia

Gynoecium (/ɡaɪˈniːsi.əm, dʒɪˈniːʃi.əm/; from Ancient Greek γυνή (gunḗ) 'woman, female' and οἶκος (oîkos) 'house', pl. gynoecia) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of (one or more) pistils and is typically surrounded by the pollen-producing reproductive organs, the stamens, collectively called the androecium. The gynoecium is often referred to as the "female" portion of the flower, although rather than directly producing female gametes (i.e. egg cells), the gynoecium produces megaspores, each of which develops into a female gametophyte which then produces egg cells.

The term gynoecium is also used by botanists to refer to a cluster of archegonia and any associated modified leaves or stems present on a gametophyte shoot in mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. The corresponding terms for the male parts of those plants are clusters of antheridia within the androecium. Flowers that bear a gynoecium but no stamens are called pistillate or carpellate. Flowers lacking a gynoecium are called staminate.

The gynoecium is often referred to as female because it gives rise to female (egg-producing) gametophytes; however, strictly speaking sporophytes do not have a sex, only gametophytes do.[1][page needed] Gynoecium development and arrangement is important in systematic research and identification of angiosperms, but can be the most challenging of the floral parts to interpret.[2]

Introduction

[edit]Unlike (most) animals, plants grow new organs after embryogenesis, including new roots, leaves, and flowers.[3] In the flowering plants, the gynoecium develops in the central region of the flower as a carpel or in groups of fused carpels.[4] After fertilization, the gynoecium develops into a fruit that provides protection and nutrition for the developing seeds, and often aids in their dispersal.[5] The gynoecium has several specialized tissues.[6] The tissues of the gynoecium develop from genetic and hormonal interactions along three-major axes.[7][8] These tissue arise from meristems that produce cells that differentiate into the different tissues that produce the parts of the gynoecium including the pistil, carpels, ovary, and ovules; the carpel margin meristem (arising from the carpel primordium) produces the ovules, ovary septum, and the transmitting track, and plays a role in fusing the apical margins of carpels.[9]

Pistil

[edit]

The gynoecium may consist of one or more separate pistils. A pistil typically consists of an expanded basal portion called an ovary, an elongated section called a style and an apical structure called a stigma that receives pollen.

- The ovary (from Latin ovum, meaning egg) is the enlarged basal portion which contains placentas, ridges of tissue bearing one or more ovules (integumented megasporangia). The placentas and/or ovule(s) may be borne on the gynoecial appendages or less frequently on the floral apex.[10][11][12][13][14] The chamber in which the ovules develop is called a locule (or sometimes cell).

- The style (from Ancient Greek στῦλος, stylos, meaning a pillar) is a pillar-like stalk through which pollen tubes grow to reach the ovary. Some flowers, such as those of Tulipa, do not have a distinct style, and the stigma sits directly on the ovary. The style is a hollow tube in some plants, such as lilies, or has transmitting tissue through which the pollen tubes grow.[15]

- The stigma (from Ancient Greek στίγμα, stigma, meaning mark or puncture) is usually found at the tip of the style, the portion of the carpel(s) that receives pollen (male gametophytes). It is commonly sticky or feathery to capture pollen.

The word "pistil" comes from Latin pistillum meaning pestle. A sterile pistil in a male flower is referred to as a pistillode.

Carpels

[edit]

The pistils of a flower are considered to be composed of one or more carpels.[note 1] A carpel is the female reproductive part of the flower—usually composed of the style, and stigma (sometimes having its individual ovary, and sometimes connecting to a shared basal ovary) —and usually interpreted as modified leaves that bear structures called ovules, inside which egg cells ultimately form. A pistil may consist of one carpel (with its ovary, style and stigma); or it may comprise several carpels joined together to form a single ovary, the whole unit called a pistil. The gynoecium may present as one or more uni-carpellate pistils or as one multi-carpellate pistil. The number of carpels is denoted by terms such as tricarpellate (three carpels).

Carpels are thought to be phylogenetically derived from ovule-bearing leaves or leaf homologues (megasporophylls), which evolved to form a closed structure containing the ovules. This structure is typically rolled and fused along the margin.

Although many flowers satisfy the above definition of a carpel, there are also flowers that do not have carpels because in these flowers the ovule(s), although enclosed, are borne directly on the floral apex.[12][17] Therefore, the carpel has been redefined as an appendage that encloses ovule(s) and may or may not bear them.[18][19][20] However, the most unobjectionable definition of the carpel is simply that of an appendage that encloses an ovule or ovules.[21] Carpels vary enormously in size from a few micrometres in Balanophora involucrata[22] and in many orchids to 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) long and 12 cm (4+1⁄2 in) wide in Entada gigas.[23][24]

Types

[edit]If a gynoecium has a single carpel, it is called monocarpous. If a gynoecium has multiple, distinct (free, unfused) carpels, it is apocarpous. If a gynoecium has multiple carpels "fused" into a single structure, it is syncarpous. A syncarpous gynoecium can sometimes appear very much like a monocarpous gynoecium.

| Gynoecium composition | Carpel terminology |

Pistil terminology | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single carpel | Monocarpous (unicarpellate) gynoecium | A pistil (simple) | Avocado (Persea sp.), most legumes (Fabaceae) |

| Multiple distinct ("unfused") carpels | Apocarpous (choricarpous) gynoecium | Pistils (simple) | Strawberry (Fragaria sp.), Buttercup (Ranunculus sp.) |

| Multiple connate ("fused") carpels | Syncarpous gynoecium | A pistil (compound) | Tulip (Tulipa sp.), most flowers |

The degree of connation ("fusion") in a syncarpous gynoecium can vary. The carpels may be "fused" only at their bases, but retain separate styles and stigmas. The carpels may be "fused" entirely, except for retaining separate stigmas. Sometimes (e.g., Apocynaceae) carpels are fused by their styles or stigmas but possess distinct ovaries. In a syncarpous gynoecium, the "fused" ovaries of the constituent carpels may be referred to collectively as a single compound ovary. It can be a challenge to determine how many carpels fused to form a syncarpous gynoecium. If the styles and stigmas are distinct, they can usually be counted to determine the number of carpels. Within the compound ovary, the carpels may have distinct locules divided by walls called septa. If a syncarpous gynoecium has a single style and stigma and a single locule in the ovary, it may be necessary to examine how the ovules are attached. Each carpel will usually have a distinct line of placentation where the ovules are attached.

Pistil

[edit]Pistils begin as small primordia on a floral apical meristem, forming later than, and closer to the (floral) apex than sepal, petal and stamen primordia. Morphological and molecular studies of pistil ontogeny reveal that carpels are most likely homologous to leaves.[citation needed]

A carpel has a similar function to a megasporophyll, but typically includes a stigma, and is fused, with ovules enclosed in the enlarged lower portion, the ovary.[25]

In some basal angiosperm lineages, including Degeneriaceae and Winteraceae, a carpel begins as a shallow cup where the ovules develop with laminar placentation, on the upper surface of the carpel. The carpel eventually forms a folded, leaf-like structure, not fully sealed at its margins. No style exists, but a broad stigmatic crest along the margin allows pollen tubes access along the surface and between hairs at the margins.[25]

Two kinds of fusion have been distinguished: postgenital fusion that can be observed during the development of flowers, and congenital fusion that cannot be observed i.e., fusions that occurred during phylogeny. But it is very difficult to distinguish fusion and non-fusion processes in the evolution of flowering plants. Some processes that have been considered congenital (phylogenetic) fusions appear to be non-fusion processes such as, for example, the de novo formation of intercalary growth in a ring zone at or below the base of primordia.[26][27][28] Therefore, "it is now increasingly acknowledged that the term 'fusion', as applied to phylogeny (as in 'congenital fusion') is ill-advised".[29]

Gynoecium position

[edit]Basal angiosperm groups tend to have carpels arranged spirally around a conical or dome-shaped receptacle. In later lineages, carpels tend to be in whorls.

The relationship of the other flower parts to the gynoecium can be an important systematic and taxonomic character. In some flowers, the stamens, petals, and sepals are often said to be "fused" into a "floral tube" or hypanthium. However, as Leins & Erbar (2010) pointed out, "the classical view that the wall of the inferior ovary results from the "congenital" fusion of dorsal carpel flanks and the floral axis does not correspond to the ontogenetic processes that can actually be observed. All that can be seen is an intercalary growth in a broad circular zone that changes the shape of the floral axis (receptacle)".[28] And what happened during evolution is not a phylogenetic fusion but the formation of a unitary intercalary meristem. Evolutionary developmental biology investigates such developmental processes that arise or change during evolution.

If the hypanthium is absent, the flower is hypogynous, and the stamens, petals, and sepals are all attached to the receptacle below the gynoecium. Hypogynous flowers are often referred to as having a superior ovary. This is the typical arrangement in most flowers.

If the hypanthium is present up to the base of the style(s), the flower is epigynous. In an epigynous flower, the stamens, petals, and sepals are attached to the hypanthium at the top of the ovary or, occasionally, the hypanthium may extend beyond the top of the ovary. Epigynous flowers are often referred to as having an inferior ovary. Plant families with epigynous flowers include orchids, asters, and evening primroses.

Between these two extremes are perigynous flowers, in which a hypanthium is present, but is either free from the gynoecium (in which case it may appear to be a cup or tube surrounding the gynoecium) or connected partly to the gynoecium (with the stamens, petals, and sepals attached to the hypanthium part of the way up the ovary). Perigynous flowers are often referred to as having a half-inferior ovary (or, sometimes, partially inferior or half-superior). This arrangement is particularly frequent in the rose family and saxifrages.

Occasionally, the gynoecium is born on a stalk, called the gynophore, as in Isomeris arborea.

-

Flowers and fruit (capsules) of the ground orchid, Spathoglottis plicata, illustrating an inferior ovary.

-

Illustration showing longitudinal sections through hypogynous (a), perigynous (b), and epigynous (c) flowers

Placentation

[edit]Within the ovary, each ovule is born by a placenta or arises as a continuation of the floral apex. The placentas often occur in distinct lines called lines of placentation. In monocarpous or apocarpous gynoecia, there is typically a single line of placentation in each ovary. In syncarpous gynoecia, the lines of placentation can be regularly spaced along the wall of the ovary (parietal placentation), or near the center of the ovary. In the latter case, separate terms are used depending on whether or not the ovary is divided into separate locules. If the ovary is divided, with the ovules born on a line of placentation at the inner angle of each locule, this is axile placentation. An ovary with free central placentation, on the other hand, consists of a single compartment without septae and the ovules are attached to a central column that arises directly from the floral apex (axis). In some cases a single ovule is attached to the bottom or top of the locule (basal or apical placentation, respectively).

The ovule

[edit]

In flowering plants, the ovule (from Latin ovulum meaning small egg) is a complex structure born inside ovaries. The ovule initially consists of a stalked, integumented megasporangium (also called the nucellus). Typically, one cell in the megasporangium undergoes meiosis resulting in one to four megaspores. These develop into a megagametophyte (often called the embryo sac) within the ovule. The megagametophyte typically develops a small number of cells, including two special cells, an egg cell and a binucleate central cell, which are the gametes involved in double fertilization. The central cell, once fertilized by a sperm cell from the pollen becomes the first cell of the endosperm, and the egg cell once fertilized become the zygote that develops into the embryo. The gap in the integuments through which the pollen tube enters to deliver sperm to the egg is called the micropyle. The stalk attaching the ovule to the placenta is called the funiculus.

Role of the stigma and style

[edit]Stigmas can vary from long and slender to globe-shaped to feathery. The stigma is the receptive tip of the carpel(s), which receives pollen at pollination and on which the pollen grain germinates. The stigma is adapted to catch and trap pollen, either by combining pollen of visiting insects or by various hairs, flaps, or sculpturings.[30]

The style and stigma of the flower are involved in most types of self incompatibility reactions. Self-incompatibility, if present, prevents fertilization by pollen from the same plant or from genetically similar plants, and ensures outcrossing.

The primitive development of carpels, as seen in such groups of plants as Tasmannia and Degeneria, lack styles and the stigmatic surface is produced along the carpels margins.[31]

-

Stigmas and style of Cannabis sativa held in a pair of forceps

-

Stigma of a Crocus flower.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Judd, W.S.; Campbell, C.S.; Kellogg, E.A.; Stevens, P.F. & Donoghue, M.J. (2007). Plant Systematics: A Phylogenetic Approach (3rd ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87893-407-2.

- ^ Sattler, R. (1974). "A new approach to gynoecial morphology". Phytomorphology. 24: 22–34.

- ^ Moubayidin, Laila; Østergaard, Lars (2017-08-01). "Gynoecium formation: an intimate and complicated relationship". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 45: 15–21. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2017.02.005. ISSN 0959-437X. PMID 28242478.

- ^ Recent Advances and Challenges on Big Data Analysis in Neuroimaging Archived 2023-01-19 at the Wayback Machine. Frontiers Media SA; 17 May 2017. ISBN 978-2-88945-128-9. p. 158–.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Reproduction Archived 2023-01-19 at the Wayback Machine. Elsevier Science; 29 June 2018. ISBN 978-0-12-815145-7. p. 2–.

- ^ Molecular basis of fruit development Archived 2023-01-19 at the Wayback Machine. Frontiers Media SA; 26 March 2014. ISBN 978-2-88919-460-5. p. 27–.

- ^ Peréz-Mesa, Pablo; Ortíz-Ramírez, Clara Inés; González, Favio; Ferrándiz, Cristina; Pabón-Mora, Natalia (2020-02-17). "Expression of gynoecium patterning transcription factors in Aristolochia fimbriata (Aristolochiaceae) and their contribution to gynostemium development". EvoDevo. 11 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s13227-020-00149-8. ISSN 2041-9139. PMC 7027301. PMID 32095226.

- ^ Simonini, Sara; Østergaard, Lars (2019). "Female reproductive organ formation: A multitasking endeavor". Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 131: 337–371. doi:10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.10.004. ISBN 9780128098042. ISSN 1557-8933. PMID 30612622. S2CID 58606227.

- ^ Fruit Ripening: From Present Knowledge to Future Development Archived 2023-01-19 at the Wayback Machine. Frontiers Media SA; 12 August 2019. ISBN 978-2-88945-919-3. p. 155–.

- ^ Macdonald, A.D. & Sattler, R. (1973). "Floral development of Myrica gale and the controversy over floral theories". Canadian Journal of Botany. 51 (10): 1965–1975. doi:10.1139/b73-251.

- ^ Sattler, R. (1973). Organogenesis of Flowers : a Photographic Text-Atlas. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-1864-9.

- ^ a b Sattler, R. & Lacroix, C. (1988). "Development and evolution of basal cauline placentation: Basella rubra". American Journal of Botany. 75 (6): 918–927. doi:10.2307/2444012. JSTOR 2444012.

- ^ Sattler, R. & Perlin, L. (1982). "Floral development of Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd., Boerhaavia diffusa L. and Mirabilis jalapa L. (Nyctaginaceae)". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 84 (3): 161–182. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1982.tb00532.x.

- ^ Greyson 1994, p. 130.

- ^ Esau, K. (1965). Plant Anatomy (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. OCLC 263092258.

- ^ "Carpophyl". The Century Dictionary: The Century dictionary. Century Company. 1914. p. 832. Archived from the original on 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ D'Arcy, W.G.; Keating, R.C. (1996). The Anther: Form, Function, and Phylogeny. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521480635. Archived from the original on 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ Greyson, R. I. 1994. The Development of Flowers. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Leins, P. and Erbar, C. 2010. Flower and Fruit. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers

- ^ Sattler, R. (2024). "Morpho evo-devo of the gynoecium: heterotopy, redefinition of the carpel, and a topographic approach". Plants. 13 (5): 599. Bibcode:2024Plnts..13..599S. doi:10.3390/plants13050599. PMC 10935004. PMID 38475445.

- ^ Sattler, R. (2024). "Morpho evo-devo of the gynoecium: heterotopy, redefinition of the carpel, and a topographic approach". Plants. 13 (5): 599. Bibcode:2024Plnts..13..599S. doi:10.3390/plants13050599. PMC 10935004. PMID 38475445.

- ^ V.H. Heywood, ed. (1978). Flowering Plants of the World. New York: Mayflower Books. p. 176.

- ^ Dodge, Charles R. (1897). A Descriptive Catalogue of the Useable Fiber Plants of the World. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 157.

- ^ Liberty Hyde Bailey, editor Cyclopedia of Horticulture Volume 1 page 1116.

- ^ a b Gifford, E.M. & Foster, A.S. (1989). Morphology and Evolution of Vascular Plants (3rd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman & Co. ISBN 978-0-7167-1946-5.

- ^ Sattler, R. (1978). "'Fusion' and 'continuity' in floral morphology". Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. 36 (2): 397–405. doi:10.24823/nrbge.1978.3127.

- ^ Greyson 1994, p. 67–69, 142–145.

- ^ a b Leins, P. & Erbar, C. (2010). Flower and Fruit. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers. ISBN 978-3-510-65261-7.

- ^ Greyson 1994, p. 142.

- ^ Blackmore, Stephen & Toothill, Elizabeth (1984). The Penguin Dictionary of Botany. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-051126-0.

- ^ Armen Takhtajan. Flowering Plants Archived 2023-01-19 at the Wayback Machine. Springer Science & Business Media; 6 July 2009. ISBN 978-1-4020-9609-9. p. 22–.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rendle, Alfred Barton (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 553–573.

- Greyson, R. I. (1994). The Development of Flowers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506688-3.