Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cultigen

View on WikipediaA cultigen (from Latin cultus 'cultivated' and gens 'kind'), or cultivated plant,[note 1] is a plant that has been deliberately altered or selected by humans,[2] by means of genetic modification, graft-chimaeras, plant breeding, or wild or cultivated plant selection. These plants have commercial value in horticulture, agriculture and forestry. Plants meeting this definition remain cultigens whether they are naturalised, deliberately planted in the wild, or grown in cultivation.

Naming

[edit]The traditional method of scientific naming is under the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, and many of the most important cultigens, like maize (Zea mays) and banana (Musa acuminata), are named. The items in the list can be in any rank.[3] It is more common currently for cultigens to be given names in accordance with the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP) principles, rules and recommendations, which provide for the names of cultigens in three categories: the cultivar, the Group (formerly the cultivar-group), and the grex.[note 2] The ICNCP does not recognize the use of trade designations and other marketing devices as scientifically acceptable names; it does provide advice on how they should be presented.[4]

Not all cultigens have been given names according to the ICNCP. Apart from ancient cultigens, there may be occasional anthropogenic plants, such as those that are the result of breeding, selection, and tissue grafting, that are considered of no commercial value and have therefore not been given names according to the ICNCP.

Origin of term

[edit]

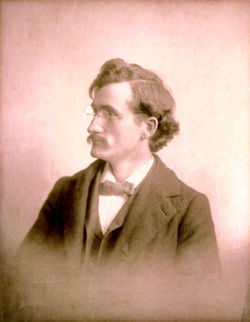

The word cultigen was coined in 1918[5] by Liberty Hyde Bailey (1858–1954), an American horticulturist, botanist and cofounder of the American Society for Horticultural Science. He created the term from the thought of a need for special categories for cultivated plants that had arisen by intentional human activity and which would not fit neatly into the Linnaean hierarchical classification of ranks used by the International Rules of Botanical Nomenclature (which later became the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants).

In his 1918 paper, Bailey noted that for anyone preparing a descriptive account of the cultivated plants of a region (he was at that time preparing such an account for North America), it would be clear that there are two gentes or kinds (Latin singular gens, plural gentes) of plants. Firstly, he referred to those that are of known origin or nativity "of known habitat" as indigens; the other kind was "a domesticated group of which the origin may be unknown or indefinite, which has such characters as to separate it from known indigens, and which is probably not represented by any type specimen or exact description, having, therefore, no clear taxonomic beginning".

He called this second kind of plant a cultigen; the word was thought to be derived from the combination of the Latin cultus ('cultivated') and gens ('kind'). In 1923, Bailey emphasised that he was dealing with plants at the rank of species, referring to indigens as those that are discovered in the wild and cultigens as plants that arise in some way under the hand of man.[6] He then defined a cultigen as a species, or its equivalent, that has appeared under domestication. Bailey soon altered his 1923 definition of cultigen when, in 1924, he gave a new definition in the Glossary of his Manual of Cultivated Plants[7] as:

Plant or group known only in cultivation; presumably originating under domestication; contrast with indigen

Cultivars

[edit]The 1924 definition of the cultigen permits the recognition of cultivars; the 1923 definition restricts the idea of the cultigen to plants at the rank of species. In later publications of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium, Cornell, the idea of the cultigen having the rank of species returned (e.g., Hortus Second in 1941 and Hortus Third in 1976).[8][9] Both of these publications indicate that the terms cultigen and cultivar are not synonymous and that cultigens exist at the rank of species only.

A cultigen is a plant or group of apparent specific rank, known only in cultivation, with no determined nativity, presumably having originated, in the form in which we know it, under domestication. Compare indigen. Examples are Cucurbita maxima, Phaseolus vulgaris, Zea mays.

Botanical historian Alan Morton thought that wild and cultivated plants (cultigens) were of interest to the ancient Greek botanists (partly for religious reasons) and that the distinction was discussed in some detail by Theophrastus, the "Father of Botany". Theophrastus accepted the view that it was human action, not divine intervention, that produced cultivated plants (cultigens) from wild plants, and he also "had an inkling of the limits of culturally induced (phenotypic) changes and of the importance of genetic constitution" (Historia Plantarum III, 2,2 and Causa Plantarum I, 9,3). He also states that cultivated varieties of fruit trees would degenerate if cultivated from seed.[10]

In his 1923 paper, Bailey established a new category for the cultivar. Bailey was never explicit about the etymology of the word cultivar; it has been suggested that it is a contraction of the words cultigen or cultivated and variety.[11] He defined cultivar in his 1923 paper as:

a race subordinate to species, that has originated and persisted under cultivation; it is not necessarily, however, referable to a recognised botanical species. It is essentially the equivalent of the botanical variety except in respect to its origin

Usage

[edit]In botany

[edit]In botanical literature, the word cultigen is generally used to denote a plant that, like the bread wheat (Triticum aestivum), is of unknown origin or presumed to be an ancient human selection. Plants like bread wheat have been given binomials according to the Botanical Code and therefore have names with the same form as those of plant species that occur naturally in the wild, but it is not necessary for a cultigen to have a species name or to have the biological characteristics that distinguish a species. Cultigens can have names at any of various other ranks, including cultivar names, names in the categories of grex and group, variety names, and forma names, or they may be plants that have been altered by humans (including genetically modified plants) but which have not been given formal names.[12]

In horticulture

[edit]In 1918, L.H. Bailey distinguished native plants from those originating in cultivation by designating the former as indigens (indigenous or native to the region) and the latter as cultigens. At the same time, he proposed the term cultivar to distinguish varieties originating in cultivation from botanical varieties known first in the wild.[13] In 1953, the first International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants was published, in which Bailey's term cultivar was introduced. In the same year, the eponymous journal commemorating the work of Bailey (who died in 1954), Baileya, was published. In the first volume of Baileya George Lawrence, taxonomist and colleague of Bailey, wrote a short article on the distinction between the new terms cultivar and variety, and to clarify the term taxon, which had been introduced by German biologist Meyer in the 1920s. He opens the article:

In horticulture, the definitions and uses of the terms cultigen and cultivar have varied, and a wider use of the term cultigen has been proposed.[2] The definition given in the Botanical Glossary of The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening defines a cultigen as "a plant found only in cultivation or in the wild having escaped from cultivation; included here are many hybrids and cultivars".[14] The Cultivated Plant Code states that cultigens are "maintained as recognisable entities solely by continued propagation"[4] and thus would not include plants that have evolved after escape from cultivation.

Recent usage in horticulture has maintained a distinction between cultigen and cultivar while allowing the inclusion of cultivars within the definition of cultigen. Cultigen is a general-purpose term encompassing plants with cultivar names and others as well, while cultivar is a formal category in the ICNCP. The definition refers to a "deliberate" (long-term propagation) selection of particular plant characteristics that are not exhibited by a plant's wild counterparts. Occasionally, cultigens escape from cultivation and go into the wild, where they breed with indigenous plants. Selections may be made from the progeny in the wild and brought back into cultivation where they are used for breeding, and the results of the breeding again escape into the wild to breed with indigenous plants; an example of this is the plant Lantana.[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brickell, C.D.; Alexander, C.; Cubey, J.J.; David, J.C.; Hoffman, M.H.A.; Leslie, A.C.; Malécot, V.; Jin, Xiaobai (2016). International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (PDF) (9th ed.). Leuven: International Society for Horticultural Science. p. 144. ISBN 978-94-6261-116-0. OCLC 1029031329. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2020-09-20.

- ^ a b Spencer & Cross 2007

- ^ McNeill, J.; Barrie, F.R.; Buck, W.R.; Demoulin, V.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Marhold, K.; Prado, J.; Prud'homme Van Reine, W.F.; Smith, G.F.; Wiersema, J.H.; Turland, N.J. (2012). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code) adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011. Vol. Regnum Vegetabile 154. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag KG. ISBN 978-3-87429-425-6. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2014-07-28. Art. 28 "Note 3. Nothing precludes the use, for cultivated plants, of names published in accordance with the requirements of this Code."

- ^ a b Brickell CD, Alexander C, David JC, Hetterscheid WA, Leslie AC, Malecot V, Jin X (2009). International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP or Cultivated Plant Code) incorporating the Rules and Recommendations for naming plants in cultivation, Eighth Edition, Adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences International Commission for the Nomenclature of Cultivated Plants (PDF). Editorial committee; Cubey, J.J. International Association for Plant Taxonomy and International Society for Horticultural Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-13. Retrieved 2014-07-28. Article 10 and Appendix 10.

- ^ Bailey, L. H. 1918. The indigen and cultigen. Science ser. 2, 47:306–308

- ^ Bailey, L. H. 1923. Various cultigens, and transfers in nomenclature. Gentes Herb. 1:113–136

- ^ L. H., Bailey (1925). Manual of cultivated plants: A flora for the identification of the most common or significant species of plants grown in the continental United States and Canada, for food, ornament, utility, and general interest, both in the open and under glass. Macmillan Publishers. ASIN B00085D7ZC.

- ^ Hyde Bailey, Liberty; Zoe Bailey, Ethel (January 1, 1949). Hortus Second a Concise Dictionary of Gardening, General Horticulture and Cultivated Plants in North America. MacMillan & Company. ASIN B000YT68Y4.

- ^ Hortus Third: A Concise Dictionary of Plants Cultivated in the United States and Canada. Macmillan Publishers. November 1, 1976. ISBN 978-0025054707.

- ^ Alan G., Morton (1981). History of Botanical Science: An Account of the Development of Botany from Ancient Times to the Present Day (reprinted 3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 9780125083829.

- ^ Trehane, P. 2004. 50 years of the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants. Acta Horticulturae 634: 17-27.

- ^ Spencer, Roger; Cross, Robert; Lumley, Peter (2007). Plant Names: A Guide to Botanical Nomenclature. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-643-09440-6.

- ^ Lawrence, George H. M. 1953. "Cultivar, Distinguished from Variety". Baileya 1: 19–20.

- ^ Huxley, Anthony (1992). Griffiths, Mark (ed.). The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening. Vol. 4. Contributed by the Royal Horticultural Society. Macmillan, London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 9781561590018.

Footnotes

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Spencer, Roger D.; Cross, Robert G. (2007). "The International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN), the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP), and the cultigen". Taxon. 56 (3): 938–940. doi:10.2307/25065875. JSTOR 25065875.

- Spencer, Roger; Cross, Robert; Lumley, Peter (2007). Plant names: a guide to botanical nomenclature. (3rd ed.). Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing (also Earthscan, UK.). ISBN 978-0-643-09440-6.

External links

[edit]- [1] Archived 2021-04-26 at the Wayback Machine Proposal of the term cultigen at the V International Symposium on the Taxonomy of Cultivated Plants 2008

- [2] International Society for Horticultural Science (includes links to the Botanical Code, Cultivated Plant Code and web sites of International Cultivar Registration Authorities). Retrieved 2009-09-16.

Cultigen

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Etymology

Definition

A cultigen is a cultivated plant whose origin, development, or existence is primarily due to intentional human selection, breeding, or cultivation, often featuring no known wild progenitor or only obscure wild ancestry. This term encompasses domesticated forms that have undergone significant human-mediated evolution, distinguishing them as products of anthropogenic influence rather than natural processes.[2] Key characteristics of cultigens include morphological alterations resulting from domestication, such as non-shattering seed heads in cereal grains that prevent natural dispersal and reduced bitterness in fruits to enhance palatability.[5] These changes often render cultigens dependent on humans for reproduction and survival, as traits like seed retention or vegetative propagation eliminate their ability to thrive independently in the wild; for instance, modern corn (Zea mays) exemplifies this, with its large, enclosed kernels derived from teosinte but now incapable of self-propagation without human planting.[6][7] Cultigens differ fundamentally from wild species, which occur and evolve naturally without human intervention, retaining traits suited to unaided survival and reproduction. They also contrast with landraces, which are locally adapted populations of cultivated plants that maintain greater genetic diversity and partial independence from human care compared to more intensively selected cultigens.[8] As a broad category derived from the portmanteau of "cultivated" and "gen" (from Latin gēns, meaning kind or race), cultigens include subsets like cultivars, which are formally named variants within this group.[2]Etymology

The term "cultigen" is a portmanteau derived from the Latin noun cultus, meaning "cultivation," "tending," or "care" (from the verb colere, "to till" or "cultivate"), combined with the suffix "-gen," shortened from genus, denoting "kind," "race," or "origin," to describe organisms primarily shaped by human intervention.[9][10] This linguistic construction emphasizes the artificial selection and propagation inherent in such plants, aligning with the broader conceptual definition of cultigens as distinct from wild species. The roots of this terminology trace back to Roman agricultural writings, where cultus frequently referred to the deliberate husbandry of crops and livestock, as detailed in Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella's De Re Rustica (c. 60–65 CE), a comprehensive treatise on farm management and domestication practices, though no precise ancient equivalent for "cultigen" appears in these texts.[11] Earlier Greco-Roman influences, including Greek genos (kind or race) underlying genus, further inform the suffix, reflecting a long-standing distinction between natural and tended forms in classical agronomy. By the 19th century, English and French botanical literature commonly employed phrases such as "cultivated plant" to discuss human-modified species, as seen in Alphonse de Candolle's Origine des Plantes Cultivées (1882), which systematically analyzed the geographic and historical origins of domesticated flora and set the stage for more specialized nomenclature.[12] The word entered scientific discourse in the early 20th century through botanical proposals and achieved wider adoption in English-language botany by the mid-20th century, evolving alongside formalized systems for classifying human-altered organisms.[13]Historical Development

Early Cultivation Practices

The Neolithic Revolution, marking the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agriculture, began approximately 12,000 to 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East, where humans first domesticated key plant species through intentional cultivation.[14] This period saw the emergence of farming practices that transformed wild plants into early cultigens, primarily focusing on cereals like einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum) and emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum), alongside barley (Hordeum vulgare), lentils (Lens culinaris), peas (Pisum sativum), chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia), and flax (Linum usitatissimum).[14] Archaeological evidence from sites such as Abu Hureyra in Syria indicates the presence of domesticated einkorn and emmer wheat around 10,000 years ago, as humans began selecting and replanting seeds from plants exhibiting desirable traits.[14] These practices laid the foundation for permanent settlements and surplus food production, fundamentally altering human societies.[15] Similar domestication processes unfolded independently in other regions, adapting to local environments and available wild flora. In Mesoamerica, agriculture emerged around 7,000 years ago, with the domestication of maize (Zea mays) from teosinte, alongside beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and squash (Cucurbita spp.), as evidenced by phytolith remains from sites like Guilá Naquitz cave in Mexico.[16] In China, millet (Panicum miliaceum and Setaria italica) was domesticated in the Yellow River basin by about 10,000 years ago, while rice (Oryza sativa) cultivation began in the Yangtze River basin around 8,000 years ago, supported by carbonized grain finds from sites like Pengtoushan.[17][18] These regional developments highlight how early humans exploited diverse ecosystems, leading to parallel evolutions of cultigens tailored to specific climates and needs. The core processes of early cultivation involved selective breeding, where humans preferentially harvested and replanted seeds from plants with advantageous traits such as larger seeds, higher yields, improved taste, and non-shattering seed heads that retained grains for easier collection.[19] This artificial selection gradually reduced the plants' natural dispersal mechanisms, creating a dependency on human intervention for reproduction and survival, as seen in the genetic shift from brittle-rachis wild wheats to tough-rachis domesticated forms.[20] Archaeological evidence from Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, dating to the 10th millennium BCE, reveals early cereal processing activities, including grinding stones with residues of wild einkorn and barley, suggesting proto-agricultural manipulation that preceded full domestication and supported communal feasting.[21] Over generations, this repeated human selection fostered genetic bottlenecks and trait fixation, transforming wild progenitors into cultigens incapable of thriving without cultivation.[22]Coining of the Term

The term "cultigen" was coined by American botanist Liberty Hyde Bailey in 1918, in his article "The Indigen and Cultigen" published in Science, to denote a plant or group of plants known only in cultivation and originating under domestication, in contrast to wild "indigens."[23] Bailey's proposal arose from the need to formally recognize ontological differences between wild and cultivated plants in systematic botany, particularly where origins of the latter were obscure or irrelevant to their classification.[24] The etymology derives from "cultivated" combined with the suffix "-gen" (as in "indigen"), emphasizing human agency in the plant's development.[25] Bailey refined the concept in subsequent works, such as his 1923 publication in Gentes Herbarum, where he applied it to specific examples and introduced "cultivar" as a subdivision for distinct cultivated varieties.[26] Amid the post-World War II expansion of agricultural research, which intensified studies on crop origins and human selection, the term saw renewed application in the 1960s and 1970s. Botanists Jack R. Harlan and J.M.J. de Wet prominently advanced its use in their 1971 paper "Toward a Rational Classification of Cultivated Plants," published in Taxon, where they proposed "cultigen" specifically for plants of human origin to differentiate them from wild progenitors or natural hybrids in biosystematic frameworks.[27] Their emphasis on gene pools and crossability barriers helped solidify the term's role in distinguishing anthropogenic evolution from natural processes.[13] Adoption in formal nomenclature progressed gradually during this period, influencing the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP), initially published in 1953 and revised in 1961 and 1969. The ICNCP incorporated "cultigen" to describe assemblies of cultivated plants maintained by humans, with the term appearing in its preamble by the 1995 edition to clarify scope and reduce ambiguity in naming human-modified taxa.[24]Naming and Taxonomy

Naming Conventions

The naming of cultigens follows standardized international rules primarily governed by the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP), which adapts the binomial nomenclature system used for wild species to accommodate the unique characteristics of cultivated organisms.[28] Under this framework, the scientific name of a cultigen typically consists of the genus name in italics followed by a specific epithet, often derived from a wild progenitor, and appended with a cultivar epithet enclosed in single quotation marks to denote the cultivated variety.[28] For instance, the apple cultivar known as Granny Smith is denoted as Malus domestica 'Granny Smith', where Malus domestica represents the species and 'Granny Smith' specifies the cultivar.[28] Specific rules ensure consistency and validity in naming. Priority is given to the earliest validly published name, establishing a chronological basis for legitimacy similar to botanical nomenclature but tailored for cultivation records.[28] If the wild origin of a cultigen is unknown, no designation linking it to a wild-type species is applied, preventing speculative associations.[28] Hybrids among cultigens are indicated by a multiplication sign (×) preceding the name, such as × Cuprocyparis leylandii for a hybrid between Chamaecyparis nootkatensis and Cupressus macrocarpa, and their nomenclature adheres to ICNCP provisions distinct from those for wild hybrids.[28] Graft-chimaeras, resulting from the fusion of tissues from different plants, are named using an addition sign (+) or an intergeneric formula, like + Crataegomespilus for a graft between Crataegus and Mespilus, with the cultivar name of the scion typically retained.[28] In contrast to the stricter Latin-based requirements of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) for wild species, cultigen naming permits greater flexibility, including the use of informal or trade designations alongside scientific names to facilitate commercial and practical identification.[28] For purely ornamental cultigens established after 1958 (or 1959 for certain registrations), Latin forms are prohibited in cultivar epithets, favoring vernacular or descriptive English terms, as seen in Hibiscus syriacus BLUE BIRD ('L’Oiseau Bleu'), where BLUE BIRD serves as a trade name and 'L’Oiseau Bleu' as the registered cultivar epithet.[28] This approach balances scientific precision with the accessibility needed in horticultural and agricultural contexts.[28]Relation to Cultivars

A cultivar represents a specific category of cultigen, defined as an assemblage of cultivated plants that have been deliberately selected for particular desirable characters or combinations thereof, ensuring they remain distinct, uniform, and stable through propagation methods such as cloning or controlled seed production.[29] For instance, the 'Fuji' apple ('Fuji') is a cultivar developed within the broader cultigen Malus domestica, prized for its crisp texture, sweetness, and long storage life.[29] The term "cultivar" was coined by American horticulturist Liberty Hyde Bailey in 1923, likely as a portmanteau of "cultivated variety," though some interpretations suggest influence from his earlier term "cultigen" combined with "variety."[30] In taxonomic hierarchy, all cultivars qualify as cultigens since they originate from human selection and propagation, but the reverse is not true; many cultigens lack the formal designation of cultivar due to absence of registration or standardized propagation protocols.[29] A classic example is the Navajo corn, a traditional landrace of maize (Zea mays) developed and maintained by Indigenous Navajo communities over generations for adaptation to arid conditions, representing a cultigen through long-term human cultivation but not a registered cultivar under modern nomenclature.[31] The primary distinctions between the two lie in requirements for nomenclature and maintenance: cultivars must adhere to the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP), involving official registration with an International Cultivar Registration Authority (ICRA) to ensure stability, uniformity, and distinctiveness for commercial or scientific use, often denoted in single quotes (e.g., 'Fuji').[29] In contrast, cultigens encompass a wider spectrum of domesticated plants, including unregistered landraces, heirloom varieties, and ancient domesticated forms that may exhibit greater genetic diversity without enforced stability, reflecting broader human intervention in plant evolution over time.[32] This conceptual framework aids in distinguishing formal breeding outcomes from the diverse tapestry of human-shaped biodiversity.[29]Usage in Sciences and Practices

In Botany

In botany, cultigens are integrated into taxonomic frameworks primarily under the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP), which coordinates with the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) for species-level classification to reflect their evolutionary relationships with wild progenitors. For instance, maize (Zea mays) is placed under the genus Zea, distinguishing its domesticated form from wild teosinte relatives through morphological and genetic traits shaped by human selection. This placement facilitates phylogenetic analyses that trace domestication events, using DNA sequencing to reconstruct lineages and identify selective sweeps associated with cultivation.[32][33][5] Botanical research on cultigens employs archaeobotany to examine fossilized remains, such as carbonized seeds and phytoliths, providing direct evidence of early domestication and dispersal. These macro- and micro-remains from archaeological sites reveal morphological changes indicative of cultivation, like increased seed size in ancient grains. Complementing this, genetic studies highlight reduced nucleotide diversity in cultigens compared to wild relatives, often resulting from founder effects and bottlenecks during domestication; for example, domesticated rice (Oryza sativa) exhibits significantly lower genetic variation than its wild ancestor Oryza rufipogon due to intense selection pressures.[34][35][36][37] The study of cultigens underscores their role in biodiversity conservation, as genebanks preserve landraces and cultivars to maintain genetic resources essential for adapting to environmental stresses, thereby countering erosion from modern monocultures. However, classifying cultigens with hybrid origins presents challenges, as interspecific crosses blur phylogenetic boundaries and complicate monophyletic groupings, requiring advanced genomic tools to disentangle ancestral contributions. For example, the hybrid ancestry of cultivated strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa) involves multiple wild species, necessitating integrated morphological and molecular data for accurate taxonomy.[38][39][40][41]In Horticulture

In horticulture, cultigens play a central role in the cultivation and breeding of ornamental plants, where selective hybridization is employed to enhance aesthetic traits such as flower color, shape, and form. Breeders cross compatible species or varieties to introduce novel characteristics, as seen in the development of roses (Rosa spp.) with vibrant multicolored petals and compact forms, or tulips (Tulipa spp.) featuring bold, varied hues through interspecific crosses like T. gesneriana × T. fosteriana.[42][43] These practices rely on controlled pollination to combine desirable genetics, often followed by selection over multiple generations to stabilize traits.[44] Propagation methods further ensure the fidelity of these cultigens, particularly for woody ornamentals like roses, where grafting onto rootstocks maintains vigor and disease resistance while preserving specific aesthetic qualities. For bulbous cultigens such as tulips, in vitro techniques like somatic embryogenesis produce uniform, virus-free plants, accelerating the dissemination of new varieties.[42][43] These approaches allow horticulturists to replicate elite cultigens without genetic variation, supporting commercial garden production. The development of garden varieties, including hybrid roses and tulip cultivars, has been profoundly influenced by horticultural societies since the 18th century, which organized trials, awards, and material exchanges to promote diversity. Groups like early European and American societies facilitated the introduction and refinement of ornamental cultigens, expanding options for landscape and floral design through collaborative breeding efforts.[45] In horticulture, many such cultigens are registered as cultivars to standardize nomenclature and propagation.[46] Challenges in managing ornamental cultigens include maintaining genetic purity amid cross-pollination risks and environmental pressures. Techniques like isolated propagation and molecular markers help preserve uniformity, but narrow genetic bases in popular varieties heighten vulnerability to pests and diseases.[47] Climate change exacerbates these issues by altering temperature and rainfall patterns, potentially disrupting cultivation in key regions and increasing the invasiveness of escaped cultigens, thus threatening biodiversity.[48][49]In Agriculture

Cultigens are central to agricultural domestication, representing plants that have been selectively bred over millennia to enhance traits like yield, nutritional value, and adaptability for human use, with staples such as wheat (Triticum aestivum) and maize (Zea mays) exemplifying this dependency on human propagation.[50] These cultigens originated from wild ancestors but evolved through artificial selection to lose natural seed dispersal mechanisms, making them reliant on farming practices for survival and reproduction.[51] The economic impacts of such domestication are profound, as seen in the Green Revolution of the 1960s–1970s, where high-yield varieties of wheat and maize, developed through breeding programs led by figures like Norman Borlaug, significantly increased grain production, often doubling or more, in key regions like India and Mexico, boosting food security and agricultural economies.[52] In crop management, cultigens are managed through practices like rotation and targeted breeding to optimize productivity and resilience. Crop rotation involving cultigens such as maize, legumes, and cereals helps restore soil nutrients, suppress weeds, and break pest cycles, reducing the need for chemical inputs and promoting long-term soil health.[53] Breeding for pest resistance has produced cultigens with enhanced genetic defenses, such as maize varieties resistant to corn borers via introgressed genes from wild relatives, minimizing crop losses and supporting sustainable intensification.[54] The global trade of cultigens, accelerated by the Columbian Exchange after 1492, redistributed staples like maize from the Americas to Africa and Europe, and wheat and rice in the opposite direction, reshaping agricultural economies and enabling diverse cropping systems worldwide.[55] This exchange diversified food production but also homogenized some regional agricultures, influencing modern yield patterns.[56] Contemporary agriculture faces challenges with cultigens related to intellectual property and sustainability. Patents on hybrid cultigens, such as those for genetically modified maize seeds granting exclusive rights to developers, have incentivized private investment in breeding but restricted seed saving by farmers, sparking debates over access in developing nations.[57] Sustainability concerns arise from monoculture reliance on high-yield cultigens, which heightens risks of pest outbreaks, soil erosion, and biodiversity loss, as evidenced by increased vulnerability in uniform wheat fields to diseases like stem rust.[58] Efforts to mitigate these include diversifying cultigen portfolios and integrating agroecological practices to balance productivity with environmental resilience.[59]Examples and Case Studies

Plant Cultigens

Plant cultigens exemplify the profound transformations achieved through human domestication, resulting in species that are fundamentally altered from their wild progenitors and integral to global food systems. These domesticated plants often exhibit traits such as reduced seed dispersal mechanisms, increased edibility, and enhanced yield, selected over millennia to suit agricultural needs. Across diverse botanical families, cultigens like those in the Poaceae (grasses) and Solanaceae (nightshades) demonstrate this variability, with Poaceae providing staple grains and Solanaceae yielding versatile vegetables.[60][61] A prominent example is maize (Zea mays), domesticated from teosinte (Zea mays ssp. parviglumis) approximately 9,000 years ago in Mexico, where early farmers selected for non-shattering kernels that allowed efficient seed retention and harvesting. This shift from teosinte's brittle, dispersed rachises to maize's robust, exposed ears revolutionized grain production, enabling widespread cultivation.[62][63] In the Poaceae family, maize's domestication highlights how selective breeding amplified carbohydrate storage, making it a cornerstone of diets in the Americas and beyond.[60] Bananas (Musa spp.), particularly the seedless dessert varieties, represent another key cultigen, originating from hybrids of wild Musa acuminata subspecies in Southeast Asia around 7,000 years ago. Human-induced hybridization and selection led to triploidy (2n=3x=33), often with AAA genome constitutions, rendering fruits parthenocarpic and seedless for easier consumption and propagation via suckers. This polyploidy, facilitated by ancient cultivators, ensured sterility that preserved desirable traits but necessitated vegetative reproduction.[64][61] Coffee (Coffea arabica), a cultigen from the Rubiaceae family, was domesticated in Ethiopia around 1,000 years ago, with selections favoring higher caffeine content to enhance beverage quality and stimulate effects. Unlike annual crops, its perennial nature involved gradual propagation from wild forests, resulting in varieties with elevated caffeine levels compared to wild progenitors. Recent 2024 genomic studies confirm this Ethiopian origin and highlight selection for caffeine and disease resistance, supporting its global spread as a cash crop.[65][66] In the Solanaceae family, the potato (Solanum tuberosum) illustrates cultural and agricultural depth, domesticated from wild Solanum species in the Andean highlands near Lake Titicaca about 8,000 years ago. Andean communities developed over 3,000 varieties through selection for tuber size, taste, and frost tolerance, integrating potatoes into rituals, diets, and high-altitude farming systems that sustained pre-Columbian societies. This diversity underscores potatoes' role in fostering resilient, localized agriculture.[67][68]Animal Cultigens

While the term "cultigen" is primarily used for plants shaped by human selection, analogous processes of domestication apply to animals through artificial selection, though far less commonly referred to as such in scientific literature. These include livestock and companion species adapted for specific roles.[69] The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) exemplifies an early domesticated animal, descended from the gray wolf (Canis lupus) through a process spanning approximately 11,000 to 40,000 years ago, with recent 2025 genetic and morphological analyses indicating the emergence of distinct domestic dogs around 11,000 years ago.[70] This timeline reflects multiple waves of selection for traits like reduced aggression, enhanced sociability, and morphological adaptations such as floppy ears and juvenile facial features, enabling dogs to integrate into human societies for hunting, guarding, and herding. Breed diversity, achieved through targeted breeding over millennia, has produced specialized varieties; for instance, herding breeds like Border Collies exhibit heightened intelligence and stamina for livestock management, diverging markedly from their wild progenitors. Archaeological evidence underscores this bond, including deliberate dog burials dating to around 14,000 years ago, such as the Bonn-Oberkassel site in Germany, where a young dog was interred with human remains and grave goods, indicating ritual significance and emotional attachment akin to that for kin. The domestic chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus), another prominent example, originated from the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) in Southeast Asia, with recent archaeological evidence suggesting domestication around 3,500 years ago (1650–1250 BCE) linked to early rice-cultivating communities selecting for docility, larger body size, and prolific egg-laying.[71] Over time, human intervention has amplified reproductive traits, resulting in breeds that lay eggs year-round rather than seasonally, contrasting the wild fowl's limited output. Behavioral shifts, including reduced flightiness and increased social tolerance in flocks, further facilitated their role in poultry farming. While earlier genomic studies proposed dates up to 8,000–10,000 years ago, the cited evidence supports this later timeline associated with agricultural expansion, with spread via trade routes.[72] In livestock like dairy cattle (Bos taurus), artificial selection has profoundly altered morphology to boost productivity; for example, intensive breeding since the 19th century has increased udder size by up to 50% in high-yielding breeds like Holsteins, enhancing milk output from an average of 2,000 liters per lactation in the early 1900s to over 10,000 liters today, though this has raised concerns about udder health and mobility.[73] Such changes exemplify how human preferences drive evolutionary trajectories in domesticated animals, primarily in agrarian contexts but also in pet-keeping traditions.References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cultus#Latin