Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Catoptrics

View on Wikipedia

Catoptrics (from Ancient Greek: κατοπτρικός katoptrikós, "specular",[1] from Ancient Greek: κάτοπτρον katoptron "mirror")[2] deals with the phenomena of reflected light and image-forming optical systems using mirrors. A catoptric system is also called a catopter (catoptre).

History

[edit]Ancient Texts

[edit]Catoptrics is the title of two texts from ancient Greece:

- Catoptrics written by "Pseudo-Euclid"; although the book is attributed to Euclid,[3] its contents are a combination of knowledge dating from Euclid's time together with information which dates to the later Roman period.[4] It has been argued that the book may have been compiled by the 4th century mathematician Theon of Alexandria.[4] The book covers the mathematical theory of mirrors, particularly the images formed by plane and spherical concave mirrors.

- Catoptrics written by Hero of Alexandria, this work concerns the practical application of mirrors for visual effects. In the Middle Ages, this work was falsely ascribed to Ptolemy. It only survives in a Latin translation.[5]

The Latin translation of Alhazen's (Ibn al-Haytham) main work, Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazir),[6] exerted a great influence on Western science: for example, on the work of Roger Bacon, who cites him by name.[7] His research in catoptrics (the study of optical systems using mirrors) centred on spherical and parabolic mirrors and spherical aberration. He made the observation that the ratio between the angle of incidence and refraction does not remain constant, and investigated the magnifying power of a lens. His work on catoptrics also contains the problem known as "Alhazen's problem".[8] Alhazen's work influenced Averroes' writings on optics,[citation needed] and his legacy was further advanced through the 'reforming' of his Optics by Persian scientist Kamal al-Din al-Farisi (d. c. 1320) in the latter's Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir (The Revision of [Ibn al-Haytham's] Optics).[9][10]

Renaissance

[edit]16th century Jewish-Ferraresi physicist Rafael Mirami wrote a treatise on the subject, Compendiosa introduttione alla prima parte della specularia, which became influential in a revival of the field, and contributed towards astronomical calculations instigated by Pope Gregory XIII, that led to the creation of the Gregorian Calendar.[11][12]

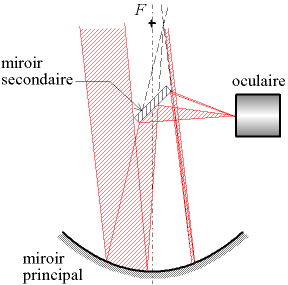

Catoptric telescopes

[edit]The first practical catoptric telescope (the "Newtonian reflector") was built by Isaac Newton as a solution to the problem of chromatic aberration exhibited in telescopes using lenses as objectives (dioptric telescopes).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jannaris, Antonius Nicholas (1895). A Concise Dictionary of the English and Modern Greek Languages: As actually written and spoken : English-Greek (in Greek and English). J. Murray.

- ^ Liddell, H.G.; Scott, R. (eds.). "κάτοπτρον". An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon. Retrieved 13 March 2015 – via perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Calvert, J.B. (2000). "Reading Euclid" (academic notes). Duke University. Retrieved 23 October 2007 – via mysite.du.edu.

- ^ a b O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Catoptrics", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews, retrieved 31 January 2013

- ^ Smith, A. Mark (1999). Ptolemy and the Foundations of Ancient Mathematical Optics. American Philosophical Society. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0871698935.

- ^ Grant, Edward (1974). A Source Book in Medieval Science. Harvard University Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-674-82360-0 – via Google.

- ^ Lindberg 1996, p. 11 passim.

- ^ Al Deek 2004.

- ^ El-Bizri 2005a.

- ^ El-Bizri 2005b.

- ^ de Aguierre y Sebastian, Matias (1654). Navidad de Zaragoza repartida en quatro noches (in Spanish). Juan de Ybar. p. 48 – via Google.

- ^ Sachar, Abram Leon (1995). Brandeis University: A host at last. Brandeis University Press / University Press of New England. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-87451-585-5. LCCN 91050821. OL 1566764M – via Google.

Bibliography

[edit]- El-Bizri, Nader (2005a). "A philosophical perspective on Alhazen's Optics". Arabic Sciences and Philosophy. 15 (2): 189–218. doi:10.1017/S0957423905000172. S2CID 123057532.

- El-Bizri, N. (2005b). "Ibn al-Haytham". In Wallis, Faith (ed.). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An encyclopedia. New York, NY & London, UK: Routledge. pp. 237–240. ISBN 0-415-96930-1. OCLC 218847614.

- Al Deek, Mahmoud, Dr. (November–December 2004). "Ibn Al-Haitham: Master of optics, mathematics, physics and medicine". Al Shindagah. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grant, Edward (1974). A Source Book in Medieval Science. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-82360-0 – via Google.

- Lindberg, David C. (1996). Roger Bacon and the Origins of Perspectiva in the Middle Ages. Clarendon Press.