Recent from talks

Contribute something

Hypatia's Mathematical and Astronomical Contributions

Main milestones

Synesius of Cyrene and Hypatia

Hypatia and Neoplatonism

The Loss of Hypatia's Writings

Hypatia and Technology: The Instruments

The Political and Religious Context of Hypatia's Murder

Hypatia and the Intellectual Climate of Alexandria

Hypatia's Life: A General Overview

Hypatia's Relationships and Social Life

Hypatia's Legacy and Memory

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hypatia

View on Wikipedia

Hypatia[a] (born c. 350–370 – March 415 AD)[1][4] was a Neoplatonist philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician who lived in Alexandria, at that time in the province of Egypt and a major city of the Eastern Roman Empire. In Alexandria, Hypatia was a prominent thinker who taught subjects including philosophy and astronomy,[5] and in her lifetime was renowned as a great teacher and a wise counselor. Not the only fourth century Alexandrian female mathematician, Hypatia was preceded by Pandrosion.[6] However, Hypatia is the first female mathematician whose life is reasonably well recorded.[7] She wrote a commentary on Diophantus's thirteen-volume Arithmetica, which may survive in part, having been interpolated into Diophantus's original text, and another commentary on Apollonius of Perga's treatise on conic sections, which has not survived. Many modern scholars also believe that Hypatia may have edited the surviving text of Ptolemy's Almagest, based on the title of her father Theon's commentary on Book III of the Almagest.

Key Information

Hypatia constructed astrolabes and hydrometers, but did not invent either of these, which were both in use long before she was born. She was tolerant toward Christians and taught many Christian students, including Synesius, the future bishop of Ptolemais. Ancient sources record that Hypatia was widely beloved by pagans and Christians alike and that she established great influence with the political elite in Alexandria. Toward the end of her life, Hypatia advised Orestes, the Roman prefect of Alexandria, who was in the midst of a political feud with Cyril, the bishop of Alexandria. Rumors spread accusing her of preventing Orestes from reconciling with Cyril and, in March 415 AD, she was murdered by a mob of Christians led by a lector named Peter.[8][9]

Hypatia's murder shocked the empire and transformed her into a "martyr for philosophy", leading future Neoplatonists such as the historian Damascius (c. 458 – c. 538) to become increasingly fervent in their opposition to Christianity. During the Middle Ages, Hypatia was co-opted as a symbol of Christian virtue and scholars believe she was part of the basis for the legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. During the Age of Enlightenment, she became a symbol of opposition to Catholicism. In the nineteenth century, European literature, especially Charles Kingsley's 1853 novel Hypatia, romanticized her as "the last of the Hellenes". In the twentieth century, Hypatia became seen as an icon for women's rights and a precursor to the feminist movement. Since the late twentieth century, some portrayals have associated Hypatia's death with the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, despite the historical fact that the library no longer existed during Hypatia's lifetime.[10]

Life

[edit]Upbringing

[edit]

Hypatia was the daughter of the mathematician Theon of Alexandria.[14][15][16] According to classical historian Edward J. Watts, Theon was the head of a school called the "Mouseion", which was named in emulation of the Hellenistic Mouseion,[15] whose membership had ceased in the 260s AD.[17] Theon's school was exclusive, highly prestigious, and doctrinally conservative. Theon rejected the teachings of Iamblichus and may have taken pride in teaching a pure, Plotinian Neoplatonism.[18] Although he was widely seen as a great mathematician at the time,[11][13][19] Theon's mathematical work has been deemed by modern standards as essentially "minor",[11] "trivial",[13] and "completely unoriginal".[19] His primary achievement was the production of a new edition of Euclid's Elements, in which he corrected scribal errors that had been made over the course of nearly 700 years of copying.[11][12][13] Theon's edition of Euclid's Elements became the most widely used edition of the textbook for centuries[12][20] and almost totally supplanted all other editions.[20]

Nothing is known about Hypatia's mother, who is never mentioned in any of the extant sources.[21][22][23] Theon dedicates his commentary on Book IV of Ptolemy's Almagest to an individual named Epiphanius, addressing him as "my dear son",[24][25] indicating that he may have been Hypatia's brother,[24] but the Greek word Theon uses (teknon) does not always mean "son" in the biological sense and was often used merely to signal strong feelings of paternal connection.[24][25] Hypatia's exact year of birth is still under debate, with suggested dates ranging from 350 to 370 AD.[26][27][28] Many scholars have followed Richard Hoche in inferring that Hypatia was born around 370. According to Damascius's lost work Life of Isidore, preserved in the entry for Hypatia in the Suda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia, Hypatia flourished during the reign of Arcadius. Hoche reasoned that Damascius's description of her physical beauty would imply that she was at most 30 at that time, and the year 370 was 30 years prior to the midpoint of Arcadius's reign.[29][30] In contrast, theories that she was born as early as 350 are based on the wording of the chronicler John Malalas (c. 491 – 578), who calls her old at the time of her death in 415.[28][31] Robert Penella argues that both theories are weakly based, and that her birth date should be left unspecified.[29]

Career

[edit]Hypatia was a Neoplatonist, but, like her father, she rejected the teachings of Iamblichus and instead embraced the original Neoplatonism formulated by Plotinus.[18] The Alexandrian school was renowned at the time for its philosophy, and Alexandria was regarded as second only to Athens as the philosophical capital of the Greco-Roman world.[26] Hypatia taught students from all over the Mediterranean.[32] According to Damascius, she lectured on the writings of Plato and Aristotle.[33][34][35][36] He also states that she walked through Alexandria in a tribon, a kind of cloak associated with philosophers, giving impromptu public lectures.[37][38][39]

According to Watts, two main varieties of Neoplatonism were taught in Alexandria during the late fourth century. The first was the overtly pagan religious Neoplatonism taught at the Serapeum, which was greatly influenced by the teachings of Iamblichus.[40] The second variety was the more moderate and less polemical variety championed by Hypatia and her father Theon, which was based on the teachings of Plotinus.[41] Although Hypatia was a pagan, she was tolerant of Christians.[42][43] In fact, every one of her known students was Christian.[44] One of her most prominent pupils was Synesius of Cyrene,[26][45][46][47] who went on to become a bishop of Ptolemais (now in eastern Libya) in 410.[47][48] Afterward, he continued to exchange letters with Hypatia[46][47][49] and his extant letters are the main sources of information about her career.[46][47][50][51][52] Seven letters by Synesius to Hypatia have survived,[46][47] but none from her addressed to him are extant.[47] In a letter written in around 395 to his friend Herculianus, Synesius describes Hypatia as "... a person so renowned, her reputation seemed literally incredible. We have seen and heard for ourselves she who honorably presides over the mysteries of philosophy."[46] Synesius preserves the legacy of Hypatia's opinions and teachings, such as the pursuit of "the philosophical state of apatheia—complete liberation from emotions and affections".[53]

The Christian historian Socrates of Constantinople, a contemporary of Hypatia, describes her in his Ecclesiastical History:[21]

There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in the presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in going to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.[33]

Philostorgius, another Christian historian, who was also a contemporary of Hypatia, states that she excelled her father in mathematics[46] and the lexicographer Hesychius of Alexandria records that, like her father, she was also an extraordinarily talented astronomer.[46][54] Damascius writes that Hypatia was "exceedingly beautiful and fair of form",[55][56] but nothing else is known regarding her physical appearance[57] and no ancient depictions of her have survived.[58] Damascius states that Hypatia remained a lifelong virgin[59][60] and that, when one of the men who came to her lectures tried to court her, she tried to soothe his lust by playing the lyre.[56][61][b] When he refused to abandon his pursuit, she rejected him outright,[56][61][63] displaying her bloody menstrual rags and declaring "This is what you really love, my young man, but you do not love beauty for its own sake."[34][56][61][63] Damascius further relates that the young man was so traumatized that he abandoned his desires for her immediately.[56][61][63]

Death

[edit]Background

[edit]

From 382 – 412, the bishop of Alexandria was Theophilus.[65] Theophilus was militantly opposed to Iamblichean Neoplatonism[65] and, in 391, he demolished the Serapeum.[66][67] Despite this, Theophilus tolerated Hypatia's school and seems to have regarded Hypatia as his ally.[21][65][68] Theophilus supported the bishopric of Hypatia's pupil Synesius,[21][69] who describes Theophilus in his letters with love and admiration.[68][70] Theophilus also permitted Hypatia to establish close relationships with the Roman prefects and other prominent political leaders.[65] Partly as a result of Theophilus's tolerance, Hypatia became extremely popular with the people of Alexandria and exerted profound political influence.[71]

Theophilus died unexpectedly in 412.[65] He had been training his nephew Cyril, but had not officially named him as his successor.[72] A violent power struggle over the diocese broke out between Cyril and his rival Timothy. Cyril won and immediately began to punish the opposing faction; he closed the churches of the Novatianists, who had supported Timothy, and confiscated their property.[73] Hypatia's school seems to have immediately taken a strong distrust toward the new bishop,[68][70] as evidenced by the fact that, in all his vast correspondences, Synesius only ever wrote one letter to Cyril, in which he treats the younger bishop as inexperienced and misguided.[70] In a letter written to Hypatia in 413, Synesius requests her to intercede on behalf of two individuals impacted by the ongoing civil strife in Alexandria,[74][75][76] insisting, "You always have power, and you can bring about good by using that power."[74] He also reminds her that she had taught him that a Neoplatonic philosopher must introduce the highest moral standards to political life and act for the benefit of their fellow citizens.[74]

According to Socrates Scholasticus, in 414, following an exchange of hostilities and a Jewish-led massacre, Cyril closed all the synagogues in Alexandria, confiscated all the property belonging to the Jews, and expelled a number of Jews from the city; Scholasticus suggests all the Jews were expelled, while John of Nikiu notes it was only those involved in the massacre.[77][78][73] Orestes, the Roman prefect of Alexandria, who was also a close friend of Hypatia[21] and a recent convert to Christianity,[21][79][80] was outraged by Cyril's actions and sent a scathing report to the emperor.[21][73][81] The conflict escalated and a riot broke out in which the parabalani, a group of Christian clerics under Cyril's authority, nearly killed Orestes.[73] As punishment, Orestes had Ammonius, the monk who had started the riot, publicly tortured to death.[73][82][83] Cyril tried to proclaim Ammonius a martyr,[73][82][84] but Christians in Alexandria were disgusted,[82][85] since Ammonius had been killed for inciting a riot and attempting to murder the governor, not for his faith.[82] Prominent Alexandrian Christians intervened and forced Cyril to drop the matter.[73][82][85] Nonetheless, Cyril's feud with Orestes continued.[86] Orestes frequently consulted Hypatia for advice[87][88] because she was well-liked among both pagans and Christians alike, she had not been involved in any previous stages of the conflict, and she had an impeccable reputation as a wise counselor.[89]

Despite Hypatia's popularity, Cyril and his allies attempted to discredit her and undermine her reputation.[90][91] Socrates Scholasticus mentions rumors accusing Hypatia of preventing Orestes from reconciling with Cyril.[88][91] Traces of other rumors that spread among the Christian populace of Alexandria may be found in the writings of the seventh-century Egyptian Coptic bishop John of Nikiû,[40][91] who alleges in his Chronicle that Hypatia had engaged in satanic practices and had intentionally hampered the church's influence over Orestes:[91][92][93][94]

And in those days there appeared in Alexandria a female philosopher, a pagan named Hypatia, and she was devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled many people through her Satanic wiles. And the governor of the city honoured her exceedingly; for she had beguiled him through her magic. And he ceased attending church as had been his custom... And he not only did this, but he drew many believers to her, and he himself received the unbelievers at his house.[92]

Murder

[edit]According to Socrates Scholasticus, during the Christian season of Lent in March 415, a mob of Christians under the leadership of a lector named Peter raided Hypatia's carriage as she was travelling home.[95][96][97] They dragged her into a building known as the Kaisarion, a former pagan temple and center of the Roman imperial cult in Alexandria that had been converted into a Christian church.[89][95][97] There, the mob stripped Hypatia naked and murdered her using ostraka,[95][98][99][100] which can either be translated as "roof tiles", "oyster shells" or simply "shards".[95] Damascius adds that they also cut out her eyeballs.[101] They tore her body into pieces and dragged her limbs through the town to a place called Cinarion, where they set them on fire.[95][101][100] According to Watts, this was in line with the traditional manner in which Alexandrians carried the bodies of the "vilest criminals" outside the city limits to cremate them as a way of symbolically purifying the city.[101][102] Although Socrates Scholasticus never explicitly identifies Hypatia's murderers, they are commonly assumed to have been members of the parabalani.[103] Christopher Haas disputes this identification, arguing that the murderers were more likely "a crowd of Alexandrian laymen".[104]

Socrates Scholasticus presents Hypatia's murder as entirely politically motivated and makes no mention of any role that Hypatia's paganism might have played in her death.[105] Instead, he reasons that "she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop."[95][106] Socrates Scholasticus unequivocally condemns the actions of the mob, declaring, "Surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort."[95][102][107]

The Canadian mathematician Ari Belenkiy has argued that Hypatia may have been involved in a controversy over the date of the Christian holiday of Easter 417 and that she was killed on the vernal equinox while making astronomical observations.[108] Classical scholars Alan Cameron and Edward J. Watts both dismiss this hypothesis, noting that there is absolutely no evidence in any ancient text to support any part of the hypothesis.[109][110]

Aftermath

[edit]Hypatia's death sent shockwaves throughout the empire;[40][111] for centuries, philosophers had been seen as effectively untouchable during the displays of public violence that sometimes occurred in Roman cities and the murder of a female philosopher at the hand of a mob was seen as "profoundly dangerous and destabilizing".[111] Although no concrete evidence was ever discovered definitively linking Cyril to the murder of Hypatia,[40] it was widely believed that he had ordered it.[40][88] Even if Cyril had not directly ordered the murder, his smear campaign against Hypatia had inspired it. The Alexandrian council was alarmed at Cyril's conduct and sent an embassy to Constantinople.[40] The advisors of Theodosius II launched an investigation to determine Cyril's role in the murder.[107]

The investigation resulted in the emperors Honorius and Theodosius II issuing an edict in autumn of 416, which attempted to remove the parabalani from Cyril's power and instead place them under the authority of Orestes.[40][107][112][113] The edict restricted the parabalani from attending "any public spectacle whatever" or entering "the meeting place of a municipal council or a courtroom."[114] It also severely restricted their recruitment by limiting the total number of parabalani to no more than five hundred.[113] According to Damascius, Cyril allegedly only managed to escape even more serious punishment by bribing one of Theodosius's officials.[107] Watts argues that Hypatia's murder was the turning point in Cyril's fight to gain political control of Alexandria.[115] Hypatia had been the linchpin holding Orestes's opposition against Cyril together, and, without her, the opposition quickly collapsed.[40] Two years later, Cyril overturned the law placing the parabalani under Orestes's control and, by the early 420s, Cyril had come to dominate the Alexandrian council.[115]

Works

[edit]Hypatia has been described as a universal genius,[116] but she was probably more of a teacher and commentator than an innovator.[117][118][21][119] No evidence has been found that Hypatia ever published any independent works on philosophy[120] and she does not appear to have made any groundbreaking mathematical discoveries.[117][118][21][119] During Hypatia's time period, scholars preserved classical mathematical works and commented on them to develop their arguments, rather than publishing original works.[117][121][122] It has also been suggested that the closure of the Mouseion and the destruction of the Serapeum may have led Hypatia and her father to focus their efforts on preserving seminal mathematical books and making them accessible to their students.[120] The Suda mistakenly states that all of Hypatia's writings have been lost,[123] but modern scholarship has identified several works by her as extant.[123] This kind of authorial uncertainty is typical of female philosophers from antiquity.[124] Hypatia wrote in Greek,[26] which was the language spoken by most educated people in the Eastern Mediterranean at the time. In classical antiquity, astronomy was seen as being essentially mathematical in character.[125] Furthermore, no distinction was made between mathematics and numerology or astronomy and astrology.[125]

Edition of the Almagest

[edit]

Hypatia is now known to have edited the existing text of Book III of Ptolemy's Almagest.[126][127][128] It was once thought that Hypatia had merely revised Theon's commentary on the Almagest,[130] based on the title of Theon's commentary on the third book of Almagest, which reads "Commentary by Theon of Alexandria on Book III of Ptolemy's Almagest, edition revised by my daughter Hypatia, the philosopher",[130][131] but, based on analysis of the titles of Theon's other commentaries and similar titles from the time period, scholars have concluded that Hypatia corrected, not her father's commentary, but the text of Almagest itself.[130][132] Her contribution is thought to be an improved method for the long division algorithms needed for astronomical computation. The Ptolemaic model of the universe was geocentric, meaning it taught that the Sun revolved around the Earth. In the Almagest, Ptolemy proposed a division problem for calculating the number of degrees swept out by the Sun in a single day as it orbits the Earth. In his early commentary, Theon had tried to improve upon Ptolemy's division calculation. In the text edited by Hypatia, a tabular method is detailed.[129] This tabular method might be the "astronomical table" which historic sources attribute to Hypatia.[129] Classicist Alan Cameron additionally states that it is possible Hypatia may have edited, not only Book III, but all nine extant books of the Almagest.[127]

Independent writings

[edit]

Hypatia wrote a commentary on Diophantus's thirteen-volume Arithmetica, which had been written sometime around the year 250 AD.[19][34][135][136] It set out more than 100 mathematical problems, for which solutions are proposed using algebra.[137] For centuries, scholars believed that this commentary had been lost.[123] Only volumes one through six of the Arithmetica have survived in the original Greek,[19][138][134] but at least four additional volumes have been preserved in an Arabic translation produced around the year 860.[19][136] The Arabic text contains numerous expansions not found in the Greek text,[19][136] including verifications of Diophantus's examples and additional problems.[19]

Cameron states that the most likely source of the additional material is Hypatia, since Hypatia is the only ancient writer known to have written a commentary on the Arithmetica and the additions appear to follow the same methods used by her father Theon.[19] The first person to deduce that the additional material in the Arabic manuscripts came from Hypatia was the nineteenth-century scholar Paul Tannery.[133][139] In 1885, Sir Thomas Heath published the first English translation of the surviving portion of the Arithmetica. Heath argued that surviving text of Arithmetica is actually a school edition produced by Hypatia to aid her students.[138] According to Mary Ellen Waithe, Hypatia used an unusual algorithm for division (in the then-standard sexagesimal numeral system), making it easy for scholars to pick out which parts of the text she had written.[133]

The consensus that Hypatia's commentary is the source of the additional material in the Arabic manuscripts of the Arithmetica has been challenged by Wilbur Knorr, a historian of mathematics, who argues that the interpolations are "of such low level as not to require any real mathematical insight" and that the author of the interpolations can only have been "an essentially trivial mind... in direct conflict with ancient testimonies of Hypatia's high caliber as a philosopher and mathematician."[19] Cameron rejects this argument, noting that "Theon too enjoyed a high reputation, yet his surviving work has been judged 'completely unoriginal.'"[19] Cameron also insists that "Hypatia's work on Diophantus was what we today might call a school edition, designed for the use of students rather than professional mathematicians."[19]

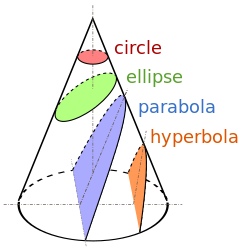

Hypatia also wrote a commentary on Apollonius of Perga's work on conic sections,[34][133][134] but this commentary is not extant.[133][134] She also created an "Astronomical Canon";[34] this is believed to have been either a new edition of the Handy Tables by the Alexandrian Ptolemy or the aforementioned commentary on his Almagest.[140][141][142] Based on a close reading in comparison with her supposed contributions to the work of Diophantus, Knorr suggests that Hypatia may also have edited Archimedes' Measurement of a Circle, an anonymous text on isometric figures, and a text later used by John of Tynemouth in his work on Archimedes' measurement of the sphere.[143] A high degree of mathematical accomplishment would have been needed to comment on Apollonius's advanced mathematics or the astronomical Canon. Because of this, most scholars today recognize that Hypatia must have been among the leading mathematicians of her day.[117]

Reputed inventions

[edit]

One of Synesius's letters describes Hypatia as having taught him how to construct a silver plane astrolabe as a gift for an official.[52][144][145][146] An astrolabe is a device used to calculate date and time based on the positions of the stars and planets. It can also be used to predict where the stars and planets will be on any given date.[144][147][148] A "little astrolabe", or "plane astrolabe", is a kind of astrolabe that used stereographic projection of the celestial sphere to represent the heavens on a plane surface, as opposed to an armillary sphere, which was globe-shaped.[129][147] Armillary spheres were large and normally used for display, whereas a plane astrolabe was portable and could be used for practical measurements.[147]

The statement from Synesius's letter has sometimes been wrongly interpreted to mean that Hypatia invented the plane astrolabe,[37][149] but the plane astrolabe was in use at least 500 years before Hypatia was born.[52][144][149][150] Hypatia may have learned how to construct a plane astrolabe from her father Theon,[129][145][147] who had written two treatises on astrolabes: one entitled Memoirs on the Little Astrolabe and another study on the armillary sphere in Ptolemy's Almagest.[147] Theon's treatise is now lost, but it was well known to the Syrian bishop Severus Sebokht (575–667), who describes its contents in his own treatise on astrolabes.[147][151] Hypatia and Theon may have also studied Ptolemy's Planisphaerium, which describes the calculations necessary in order to construct an astrolabe.[152] Synesius's wording indicates that Hypatia did not design or construct the astrolabe, but acted as a guide and mentor during the process of constructing it.[13]

In another letter, Synesius requests Hypatia to construct him a "hydroscope", a device now known as a hydrometer, to determine the density or specific gravity of liquids.[145][149][153][154] Based on this request, some writers have proposed that Hypatia invented the hydrometer.[149][155] The minute detail in which Synesius describes the instrument, however, indicates that he assumes she has never heard of the device,[156][157] but trusts she will be able to replicate it based on a verbal description. Hydrometers were based on Archimedes' 3rd century BC principles, may have been invented by him, and were being described by the 2nd century AD in a poem by the Roman author Remnius.[158][159][160] Although modern authors frequently credit Hypatia with having developed a variety of other inventions, these other attributions may all be discounted as spurious.[156] Booth concludes, "The modern day reputation held by Hypatia as a philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, and mechanical inventor, is disproportionate to the amount of surviving evidence of her life's work. This reputation is either built on myth or hearsay as opposed to evidence. Either that or we are missing all of the evidence that would support it."[155]

Legacy

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]Neoplatonism and paganism both survived for centuries after Hypatia's death,[161][162] and new academic lecture halls continued to be built in Alexandria after her death.[163] Over the next 200 years, Neoplatonist philosophers such as Hierocles of Alexandria, John Philoponus, Simplicius of Cilicia, and Olympiodorus the Younger made astronomical observations, taught mathematics, and wrote lengthy commentaries on the works of Plato and Aristotle.[161][162] Hypatia was not the last female Neoplatonist philosopher; later ones include Aedesia, Asclepigenia, and Theodora of Emesa.[163]

According to Watts, however, Hypatia had no appointed successor, no spouse, and no offspring[107][164] and her sudden death not only left her legacy unprotected, but also triggered a backlash against her entire ideology.[165] Hypatia, with her tolerance toward Christian students and her willingness to cooperate with Christian leaders, had hoped to establish a precedent that Neoplatonism and Christianity could coexist peacefully and cooperatively. Instead, her death and the subsequent failure by the Christian government to impose justice on her killers destroyed that notion entirely and led future Neoplatonists such as Damascius to consider Christian bishops as "dangerous, jealous figures who were also utterly unphilosophical."[166] Hypatia became seen as a "martyr for philosophy",[166] and her murder led philosophers to adopt attitudes that increasingly emphasized the pagan aspects of their beliefs system[167] and helped create a sense of identity for philosophers as pagan traditionalists set apart from the Christian masses.[168] Thus, while Hypatia's death did not bring an end to Neoplatonist philosophy as a whole, Watts argues that it did bring an end to her particular variety of it.[169]

Shortly after Hypatia's murder, a forged anti-Christian letter appeared under her name.[170] Damascius was "anxious to exploit the scandal of Hypatia's death", and attributed responsibility for her murder to Bishop Cyril and his Christian followers.[171][172] A passage from Damascius's Life of Isidore, preserved in the Suda, concludes that Hypatia's murder was due to Cyril's envy over "her wisdom exceeding all bounds and especially in the things concerning astronomy".[173][174] Damascius's account of the Christian murder of Hypatia is the sole historical source attributing direct responsibility to Bishop Cyril.[174] At the same time, Damascius was not entirely kind to Hypatia either; he characterizes her as nothing more than a wandering Cynic,[175][176] and compares her unfavorably with his own teacher Isidore of Alexandria,[175][176][177] remarking that "Isidorus greatly outshone Hypatia, not just as a man does over a woman, but in the way a genuine philosopher will over a mere geometer."[178]

Middle Ages

[edit]

Hypatia's death was similar to those of Christian martyrs in Alexandria, who had been dragged through the streets during the Decian persecution in 250.[182][183][184] Other aspects of Hypatia's life also fit the mold for a Christian martyr, especially her lifelong virginity.[179][185] In the Early Middle Ages, Christians conflated Hypatia's death with stories of the Decian martyrs[179][185] and she became part of the basis for the legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a virgin martyr said to have been exceedingly wise and well-educated.[179][180][181] The earliest attestation for the cult of Saint Catherine comes from the eighth century, around three hundred years after Hypatia's death.[186] One story tells of Saint Catherine being confronted by fifty pagan philosophers seeking to convert her,[181][187] but instead converting all of them to Christianity through her eloquence.[179][181] Another legend put forth that Saint Catherine had been a student of Athanasius of Alexandria.[183] In the Laodikeia of Asia Minor (today Denizli in Turkey) until late 19th century Hypatia was venerated as identical to St. Catherine.[188][189]

The Byzantine Suda encyclopedia contains a very long entry about Hypatia, which summarizes two different accounts of her life.[190] The first eleven lines come from one source and the rest of the entry comes from Damascius's Life of Isidore. Most of the first eleven lines of the entry probably come from Hesychius's Onomatologos,[191] but some parts are of unknown origin, including a statement that she was "the wife of Isidore the Philosopher" (apparently Isidore of Alexandria).[34][191][192] Watts describes this as puzzling, not only because Isidore of Alexandria was not born until long after Hypatia's death, and no other philosopher of that name contemporary with Hypatia is known,[193][194][195] but also because it contradicts Damascius's own statement quoted in the same entry about Hypatia being a lifelong virgin.[193] Watts suggests that someone probably misunderstood the meaning of the word gynē used by Damascius to describe Hypatia in his Life of Isidore, since the same word can mean either "woman" or "wife".[196]

The Byzantine and Christian intellectual Photios (c. 810/820–893) includes both Damascius's account of Hypatia and Socrates Scholasticus's in his Bibliotheke.[196] In his own comments, Photios remarks on Hypatia's great fame as a scholar, but does not mention her death, perhaps indicating that he saw her scholarly work as more significant.[197] The intellectual Eudokia Makrembolitissa (1021–1096), the second wife of Byzantine emperor Constantine X Doukas, was described by the historian Nicephorus Gregoras as a "second Hypatia".[198]

Early modern period

[edit]

Early eighteenth-century Deist scholar John Toland used the murder of Hypatia as the basis for an anti-Catholic tract,[199][200][201] portraying Hypatia's death in the worst possible light by changing the story and inventing elements not found in any of the ancient sources.[199][200] A 1721 response by Thomas Lewis defended Cyril,[199][202] rejected Damascius's account as unreliable because its author was "a heathen"[202] and argued that Socrates Scholasticus was "a Puritan", who was consistently biased against Cyril.[202]

Voltaire, in his Examen important de Milord Bolingbroke ou le tombeau de fanatisme (1736) interpreted Hypatia as a believer in "the laws of rational Nature" and "the capacities of the human mind free of dogmas"[117][199] and described her death as "a bestial murder perpetrated by Cyril's tonsured hounds, with a fanatical gang at their heels".[199] Later, in an entry for his Dictionnaire philosophique (1772), Voltaire again portrayed Hypatia as a freethinking deistic genius brutally murdered by ignorant and misunderstanding Christians.[117][203][204] Most of the entry ignores Hypatia altogether and instead deals with the controversy over whether or not Cyril was responsible for her death.[204] Voltaire concludes with the snide remark that "When one strips beautiful women naked, it is not to massacre them."[203][204]

In his monumental work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the English historian Edward Gibbon expanded on Toland and Voltaire's misleading portrayals by declaring Cyril as the sole cause of all evil in Alexandria at the beginning of the fifth century[203] and construing Hypatia's murder as evidence to support his thesis that the rise of Christianity hastened the decline of the Roman Empire.[205] He remarks on Cyril's continued veneration as a Christian saint, commenting that "superstition [Christianity] perhaps would more gently expiate the blood of a virgin, than the banishment of a saint."[206] In response to these accusations, Catholic authors, as well as some French Protestants, insisted with increased vehemence that Cyril had absolutely no involvement in Hypatia's murder and that Peter the Lector was solely responsible. In the course of these heated debates, Hypatia tended to be cast aside and ignored, while the debates focused far more intently on the question of whether Peter the Lector had acted alone or under Cyril's orders.[204]

Nineteenth century

[edit]In the nineteenth century European literary authors spun the legend of Hypatia as part of neo-Hellenism, a movement that romanticised ancient Greeks and their values.[117] Interest in the "literary legend of Hypatia" began to rise.[203] Diodata Saluzzo Roero's 1827 Ipazia ovvero delle Filosofie suggested that Cyril had actually converted Hypatia to Christianity, and that she had been killed by a "treacherous" priest.[208]

In his 1852 Hypatie and 1857 Hypathie et Cyrille, French poet Charles Leconte de Lisle portrayed Hypatia as the epitome of "vulnerable truth and beauty".[211] Leconte de Lisle's first poem portrayed Hypatia as a woman born after her time, a victim of the laws of history.[206][212] His second poem reverted to the eighteenth-century Deistic portrayal of Hypatia as the victim of Christian brutality,[210][213] but with the twist that Hypatia tries and fails to convince Cyril that Neoplatonism and Christianity are actually fundamentally the same.[210][214] Charles Kingsley's 1853 novel Hypatia; Or, New Foes with an Old Face was originally intended as a historical treatise, but instead became a typical mid-Victorian romance with a militantly anti-Catholic message,[215][216] portraying Hypatia as a "helpless, pretentious, and erotic heroine"[217] with the "spirit of Plato and the body of Aphrodite."[218]

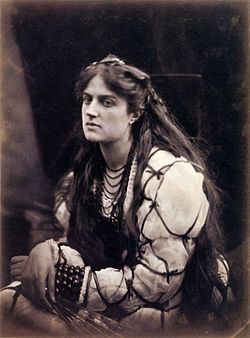

Kingsley's novel was tremendously popular;[219][220] it was translated into several European languages[220][221] and remained continuously in print for the rest of the century.[221] It promoted the romantic vision of Hypatia as "the last of the Hellenes"[220] and was quickly adapted into a broad variety of stage productions, the first of which was a play written by Elizabeth Bowers, performed in Philadelphia in 1859, starring the writer in the titular role.[221] On 2 January 1893, a much higher-profile stage play adaptation Hypatia, written by G. Stuart Ogilvie and produced by Herbert Beerbohm Tree, opened at the Haymarket Theatre in London. The title role was initially played by Julia Neilson, and it featured an elaborate musical score written by the composer Hubert Parry.[222][223] The novel also spawned works of visual art,[207] including an 1867 image portraying Hypatia as a young woman by the early photographer Julia Margaret Cameron[207][224] and an 1885 painting Hypatia by Charles William Mitchell showing a nude Hypatia standing before an altar in a church.[207]

At the same time, European philosophers and scientists described Hypatia as the last representative of science and free inquiry before a "long medieval decline".[117] In 1843, German authors Soldan and Heppe argued in their highly influential History of the Witchcraft Trials that Hypatia may have been, in effect, the first famous "witch" punished under Christian authority (see witch-hunt).[225]

Hypatia was honored as an astronomer when 238 Hypatia, a main belt asteroid discovered in 1884, was named for her. The lunar crater Hypatia was also named for her, in addition to craters named for her father Theon. The 180 km Rimae Hypatia are located north of the crater, one degree south of the equator, along the Mare Tranquillitatis.[226]

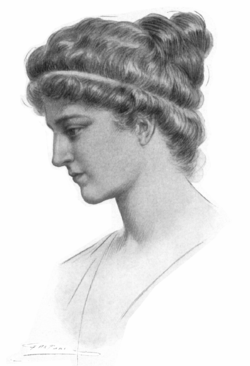

Twentieth century

[edit]In 1908, American writer Elbert Hubbard published a putative biography of Hypatia in his series Little Journeys to the Homes of Great Teachers. The book is almost entirely a work of fiction.[228][231] In it, Hubbard writes that Theon established a program of physical exercise for his daughter, involving "fishing, horseback-riding, and rowing".[232] He states that Theon taught Hypatia to "Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than to never think at all."[232] Hubbard also writes that, as a young woman, Hypatia traveled to Athens, where she studied under Plutarch of Athens. All of this supposed biographical information, however, is completely fictional and is not found in any ancient source. Hubbard even attributes to Hypatia numerous completely fabricated quotations in which she presents modern, rationalist views.[232] The cover illustration for the book, a drawing of Hypatia by artist Jules Maurice Gaspard showing her as a beautiful young woman with her wavy hair tied back in the classical style, has now become the most iconic and widely reproduced image of her.[228][229][230]

Around the same time, Hypatia was adopted by feminists, and her life and death began to be viewed in the light of the women's rights movement.[233] The author Carlo Pascal wrote in 1908 that her murder was an anti-feminist act and brought about a change in the treatment of women, as well as the decline of the Mediterranean civilization in general.[234] Dora Russell published a book on the inadequate education of women and inequality with the title Hypatia or Woman and Knowledge in 1925.[235] The prologue explains why she chose the title:[235] "Hypatia was a university lecturer denounced by Church dignitaries and torn to pieces by Christians. Such will probably be the fate of this book."[226] Hypatia's death became symbolic for some historians. For example, Kathleen Wider proposes that the murder of Hypatia marked the end of Classical antiquity,[236] and Stephen Greenblatt writes that her murder "effectively marked the downfall of Alexandrian intellectual life".[237] On the other hand, Christian Wildberg notes that Hellenistic philosophy continued to flourish in the 5th and 6th centuries, and perhaps until the age of Justinian I.[238][239]

Fables should be taught as fables, myths as myths, and miracles as poetic fantasies. To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing. The child mind accepts and believes them, and only through great pain and perhaps tragedy can he be in after years relieved of them. In fact, men will fight for a superstition quite as quickly as for a living truth–often more so, since a superstition is so intangible you can not get at it to refute it, but truth is a point of view, and so is changeable.

— Made-up quote attributed to Hypatia in Elbert Hubbard's 1908 fictional biography of her, along with several other similarly spurious quotations[232]

Falsehoods and misconceptions about Hypatia continued to proliferate throughout the late twentieth century.[231] Though Hubbard's fictional biography may have been intended for children,[229] Lynn M. Osen relied on it as her main source in her influential 1974 article on Hypatia in her 1974 book Women in Mathematics.[231] Fordham University used Hubbard's biography as the main source of information about Hypatia in a medieval history course.[228][231] Carl Sagan's 1980 PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage relates a heavily fictionalized retelling of Hypatia's death, which results in the "Great Library of Alexandria" being burned by militant Christians.[149] In actuality, though Christians led by Theophilus did destroy the Serapeum in 391 AD, the Library of Alexandria had already ceased to exist in any recognizable form centuries prior to Hypatia's birth.[10] As a female intellectual, Hypatia became a role model for modern intelligent women and two feminist journals were named after her: the Greek journal Hypatia: Feminist Studies was launched in Athens in 1984, and Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy in the United States in 1986.[233] In the United Kingdom, the Hypatia Trust maintains a library and archive of feminine literary, artistic and scientific work; and, sponsors the Hypatia-in-the-Woods women's retreat in Washington, United States.[226]

Judy Chicago's large-scale art piece The Dinner Party awards Hypatia a table setting.[240][241] The table runner depicts Hellenistic goddesses weeping over her death.[234] Chicago states that the social unrest leading to Hypatia's murder resulted from Roman patriarchy and mistreatment of women and that this ongoing unrest can only be brought to an end through the restoration of an original, primeval matriarchy.[242] She (anachronistically and incorrectly) concludes that Hypatia's writings were burned in the Library of Alexandria when it was destroyed.[234] Major works of twentieth century literature contain references to Hypatia,[243] including Marcel Proust's volume "Within a Budding Grove" from In Search of Lost Time, and Iain Pears's The Dream of Scipio.[216]

Twenty-first century

[edit]Hypatia has continued to be a popular subject in both fiction and nonfiction by authors in many countries and languages.[244] In 2015, the planet designated Iota Draconis b was named after Hypatia.[245]

In Umberto Eco's 2002 novel Baudolino, the hero's love interest is a half-satyr, half-woman descendant of a female-only community of Hypatia's disciples, collectively known as "hypatias".[246] Charlotte Kramer's 2006 novel Holy Murder: the Death of Hypatia of Alexandria portrays Cyril as an archetypal villain, while Hypatia is described as brilliant, beloved, and more knowledgeable of scripture than Cyril.[247] Ki Longfellow's novel Flow Down Like Silver (2009) invents an elaborate backstory for why Hypatia first started teaching.[248] Youssef Ziedan's novel Azazeel (2012) describes Hypatia's murder through the eyes of a witness.[249] Bruce MacLennan's 2013 book The Wisdom of Hypatia presents Hypatia as a guide who introduces Neoplatonic philosophy and exercises for modern life.[250] In The Plot to Save Socrates (2006) by Paul Levinson and its sequels, Hypatia is a time-traveler from the twenty-first century United States.[251][252][253] In the TV series The Good Place Season 4 Episode 12 "Patty", Hypatia is played by Lisa Kudrow as one of the few ancient philosophers eligible for heaven, by not having defended slavery.[254]

The 2009 film Agora, directed by Alejandro Amenábar and starring Rachel Weisz as Hypatia, is a heavily fictionalized dramatization of Hypatia's final years.[10][255][256] The film, which was intended to criticize contemporary Christian fundamentalism,[257] has had wide-ranging impact on the popular conception of Hypatia.[255] It emphasizes Hypatia's astronomical and mechanical studies rather than her philosophy, portraying her as "less Plato than Copernicus",[255] and emphasizes the restrictions imposed on women by the early Christian church,[258] including depictions of Hypatia being sexually assaulted by one of her father's Christian slaves,[259] and of Cyril reading from 1 Timothy 2:8–12 forbidding women from teaching.[259][260] The film contains numerous historical inaccuracies:[10][259][261] It inflates Hypatia's achievements[149][261] and incorrectly portrays her as finding a proof of Aristarchus of Samos's heliocentric model of the universe, which there is no evidence that Hypatia ever studied.[149] It also contains a scene based on Carl Sagan's Cosmos in which Christians raid the Serapeum and burn all of its scrolls, leaving the building itself largely intact. In reality, the Serapeum probably did not have any scrolls in it at that time,[c] and the building was demolished in 391 AD.[10] The film also implies that Hypatia is an atheist, directly contradictory to the surviving sources, which all portray her as following the teachings of Plotinus that the goal of philosophy was "a mystical union with the divine."[149]

Margaret Atwood's 2023 short story collection Old Babes in the Wood includes the story "Death by Clamshell" narrated in the first person by Hypatia.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /haɪˈpeɪʃə, -ʃiə/ ⓘ hy-PAY-shə, -shee-ə;[2][3] Ancient Greek: Ὑπατία, Koine pronunciation [y.pa.ˈti.a]

- ^ Using music to relieve lustful urges was a Pythagorean remedy[61] stemming from an anecdote from the life of Pythagoras relating that, when he encountered some drunken youths trying to break into the home of a virtuous woman, he sang a solemn tune with long spondees and the boys' "raging willfulness" was quelled.[62]

- ^ The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, writing before the Serapeum's destruction in 391 AD, refers to the Serapeum's libraries in the past tense, indicating that the libraries no longer existed by the time of the Serapeum's destruction.

References

[edit]- ^ a b O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Hypatia of Alexandria", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011), Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- ^ Benedetto, Canio; Isola, Stefano; Russo, Lucio (31 January 2017), "Dating Hypatia's birth : a probabilistic model", Mathematics and Mechanics of Complex Systems, 5 (1): 19–40, doi:10.2140/memocs.2017.5.19, hdl:11581/390549, ISSN 2325-3444

- ^ Krebs, Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries; The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, 1999: "Greek Neoplatonist philosopher who lived and taught in Alexandria."

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Pandrosion of Alexandria", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Deakin 2012.

- ^ Edward Jay Watts, (2006), City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria. "Hypatia and pagan philosophical culture in the later fourth century", pp. 197–198. University of California Press

- ^ Deakin 1994, p. 235–237.

- ^ a b c d e Theodore 2016, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b c d Deakin 2007, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Bradley 2006, p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e Booth 2017, p. 112.

- ^ Deakin, Michael (3 August 1997), Ockham's Razor: Hypatia of Alexandria, ABC Radio, retrieved 10 July 2014

- ^ a b Watts 2008, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, pp. 66–70.

- ^ Watts 2008, p. 150.

- ^ a b Watts 2008, p. 192.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cameron 2016, p. 194.

- ^ a b Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Booth 2017.

- ^ Watts 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Deakin 2007, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Deakin 2007, p. 53.

- ^ a b Dzielska 1996, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Castner 2010, p. 49.

- ^ Deakin 2007, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Dzielska 1996, p. 68.

- ^ a b Penella 1984, pp. 126–128.

- ^ Hoche 1860, pp. 435–474.

- ^ J. C. Wensdorf (1747–1748) and S. Wolf (1879), as cited by Penella (1984).

- ^ Castner 2010, p. 20.

- ^ a b Socrates of Constantinople, Ecclesiastical History

- ^ a b c d e f g "Suda online, Upsilon 166", www.stoa.org

- ^ Bregman 1982, p. 55.

- ^ Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Oakes 2007, p. 364.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 56.

- ^ Haas 1997, p. 311.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Watts 2008, p. 200.

- ^ Watts 2008, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Bregman 1982, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, p. 58.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 67–70.

- ^ a b c d e f g Waithe 1987, p. 173.

- ^ a b c d e f Curta & Holt 2017, p. 283.

- ^ Watts 2017, p. 88.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 28.

- ^ Banev 2015, p. 100.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 88–90.

- ^ a b c Bradley 2006, p. 63.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 53.

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 141.

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e Deakin 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 116.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 128–130.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b c d e Watts 2017, p. 75.

- ^ Riedweg 2005, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Booth 2017, p. 128.

- ^ Watts 2017, p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e Watts 2008, p. 196.

- ^ Wessel 2004, p. 49.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 57–61.

- ^ a b c Deakin 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Watts 2017, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Dzielska 1996, p. 95.

- ^ Watts 2008, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Watts 2008, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b c d e f g Watts 2008, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Dzielska 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Deakin 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Haas 1997, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Seaver, James Everett (1952), Persecution of the Jews in the Roman Empire (300-438), Lawrence, University of Kansas Publications, 1952.

- ^ "John of Nikiu: The Life of Hypatia", www.faculty.umb.edu, retrieved 19 July 2020

- ^ Wessel 2004, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Haas 1997, p. 312.

- ^ Wessel 2004, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e Wessel 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Haas 1997, p. 306.

- ^ Haas 1997, pp. 306–307.

- ^ a b Haas 1997, pp. 307, 313.

- ^ Haas 1997, p. 307.

- ^ Watts 2008, pp. 197–198.

- ^ a b c Novak 2010, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b Watts 2008, p. 198.

- ^ Watts 2008, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b c d Haas 1997, pp. 312–313.

- ^ a b Chronicle 84.87–103, archived from the original on 31 July 2010

- ^ John, Bishop of Nikiû, Chronicle 84.87–103

- ^ Grout, James, "Hypatia", Penelope, University of Chicago

- ^ a b c d e f g Novak 2010, p. 240.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b Haas 1997, p. 313.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 93.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b Watts 2008, pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b c Watts 2017, p. 116.

- ^ a b Watts 2008, p. 199.

- ^ Haas 1997, pp. 235–236, 314.

- ^ Haas 1997, p. 314.

- ^ Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, p. 59.

- ^ Ecclesiastical History, Bk VII: Chap. 15 (miscited as VI:15).

- ^ a b c d e Watts 2017, p. 117.

- ^ Belenkiy 2010, pp. 9–13.

- ^ Cameron 2016, p. 190.

- ^ Watts 2017, p. 157.

- ^ a b Watts 2017, p. 121.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b Haas 1997, p. 436.

- ^ Haas 1997, pp. 67, 436.

- ^ a b Watts 2008, pp. 197–200.

- ^ MacDonald, Beverley and Weldon, Andrew. (2003). Written in Blood: A Brief History of Civilization (pg. 173). Allen & Unwin.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Castner 2010, p. 50.

- ^ a b Deakin 2007, p. 111.

- ^ a b Cameron 2016, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Dzielska 2008, p. 132.

- ^ Bradley 2006, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Waithe 1987, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Engels 2009, pp. 97–124.

- ^ a b Emmer 2012, p. 74.

- ^ a b Dzielska 1996, pp. 71–2.

- ^ a b c d Cameron 2016, pp. 193–194.

- ^ a b Booth 2017, pp. 108–111.

- ^ a b c d e Emmer 2012, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Dzielska 1996, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, p. 45.

- ^ Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, pp. 45–47.

- ^ a b c d e f Waithe 1987, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e Booth 2017, p. 110.

- ^ Deakin 1992, pp. 20–22.

- ^ a b c Booth 2017, p. 109.

- ^ Bradley 2006, p. 61.

- ^ a b Deakin 1992, p. 21.

- ^ Sir Thomas Little Heath (1910), Diophantus of Alexandria; A Study in the History of Greek Algebra (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, republished 2017, pp. 14 & 18

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Deakin 1994.

- ^ Dixon, Don, COSMOGRAPHICA Space Art and Science Illustration

- ^ Knorr 1989.

- ^ a b c d Deakin 2007, pp. 102–104.

- ^ a b c Deakin 1992, p. 22.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 111–113.

- ^ a b c d e f Booth 2017, p. 111.

- ^ Pasachoff & Pasachoff 2007, p. 226.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Theodore 2016, p. 183.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Virginia Trimble; Thomas R. Williams; Katherine Bracher; Richard Jarrell; Jordan D. Marché; F. Jamil Ragep, eds. (2007), Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, Springer, pp. 1134, ISBN 978-0387304007

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Deakin 2007, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b Booth 2017, p. 115.

- ^ a b Deakin 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Bensaude-Vincent, Bernadette (2002), Holmes, Frederic L.; Levere, Trevor H. (eds.), Instruments and Experimentation in the History of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, p. 153

- ^ Ian Spencer Hornsey, A history of beer and brewing, Royal Society of Chemistry · 2003, page 429

- ^ Jeanne Bendick, Archimedes and the Door of Science, Literary Licensing, LLC · 2011, pages 63-64

- ^ a b Booth 2017, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b Watts 2017, pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b Booth 2017, p. 151.

- ^ Watts 2008, p. 201.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 117–119.

- ^ a b Watts 2017, p. 119.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Watts 2017, p. 120.

- ^ Watts 2017, p. 155.

- ^ Synodicon, c. 216, in iv. tom. Concil. p. 484, as detailed in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 8, chapter XLVII

- ^ Whitfield 1995, p. 14.

- ^ Wessel 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Rosser 2008, p. 12.

- ^ a b Dzielska 1996, p. 18.

- ^ a b Wessel 2004, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 55.

- ^ Deakin 2007, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e Deakin 2007, pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b Walsh 2007, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Booth 2017, p. 152.

- ^ Dzielska 2008, p. 141.

- ^ a b Walsh 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 150.

- ^ a b Walsh 2007, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Walsh 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Deakin 2007, p. 135.

- ^ Espetsieris K., "Icons of Greek philosophs in Churches", ("Εσπετσιέρης Κ., "Εικόνες Ελλήνων φιλοσόφων εις Εκκλησίας”), Επιστ. Επετηρίς Φιλοσοφ. Σχολ. Παν/μίου Αθηνών 14 (1963-64), pp. 391, 441 – 443 In Greek.

- ^ Espetsieris K., "Icons of Greek philosophs in Churches. Complementary information." (Εσπετσιέρης Κ., "Εικόνες Ελλήνων φιλοσόφων εις Εκκλησίας). Συμπληρωματικά στοιχεία”, Επιστ. Επετηρίς Φιλοσοφ. Σχολ. Παν/μίου Αθηνών 24 (1973-74), pp. 418-421 In Greek.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b Watts 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 130.

- ^ a b Watts 2017, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 130–131.

- ^ "Isidorus 1" entry in John Robert Martindale, (1980), The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press

- ^ a b Watts 2017, p. 130.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e f Dzielska 1996, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Watts 2017, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Ogilvie, M. B. (1986). Women in science: Antiquity through the 19th century. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- ^ a b c Watts 2017, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c d Dzielska 1996, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Watts 2017, p. 139.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Dzielska 1996, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Watts 2017, p. 142.

- ^ Saluzzo Roero, Diodata (1827), Ipazia ovvero Delle filosofie poema di Diodata Saluzzo Roero.

- ^ Grout, James, "The Death of Hypatia", Penelope, University of Chicago

- ^ a b c Booth 2017, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 8.

- ^ a b Booth 2017, p. 15.

- ^ Snyder, J.M. (1989), The woman and the lyre: Women writers in classical Greece and Rome, Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 9.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b c Dzielska 1996, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Watts 2017, p. 141.

- ^ Macqueen-Pope 1948, p. 337.

- ^ Archer 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Marsh, Jan; Nunn, Pamela Gerrish (1997), Pre-Raphaelite women artists: Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon …, Manchester City Art Galleries, ISBN 978-0-901673-55-8

- ^ Soldan, Wilhelm Gottlieb (1843), Geschichte der Hexenprozesse: aus dem Qvellen Dargestellt, Cotta, p.82.

- ^ a b c Booth 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 25–26, 28.

- ^ a b c d Deakin 2007, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Cohen 2008, p. 47.

- ^ a b Booth 2017, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d Cohen 2008, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b c d Cohen 2008, p. 48.

- ^ a b Dzielska 1996, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Booth 2017, p. 25.

- ^ a b Booth 2017, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Wider, Kathleen (1986), "Women Philosophers in the Ancient Greek World: Donning the Mantle", Hypatia, 1 (1): 21–62, doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1986.tb00521.x, JSTOR 3810062, S2CID 144952549

- ^ Greenblatt, The Swerve: how the world became modern 2011:93.

- ^ Christian Wildberg, in Hypatia of Alexandria – a philosophical martyr, The Philosopher's Zone, ABC Radio National (4 April 2009)

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 105.

- ^ Snyder, Carol (1980–1981), "Reading the Language of "The Dinner Party"", Woman's Art Journal, 1 (2): 30–34, doi:10.2307/1358081, JSTOR 1358081,

Among the raised images distributed on the first two wings of the table are two with broken edges—the Hypatia and Petronilla da Meath plates. Chicago confirmed my reading of the broken edge as a reference to the violent deaths both women suffered"

. - ^ Booth 2017, p. 22.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 14–30.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 13–20.

- ^ Pasachoff, Jay M.; Filippenko, Alex (11 July 2019), The Cosmos: Astronomy in the New Millennium, Cambridge University Press, p. 658, ISBN 978-1-108-43138-5

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 16.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Majumdar, Deepa (September 2015), "Review of The Wisdom of Hypatia", The International Journal of the Platonic Tradition, 9 (2): 261–265, doi:10.1163/18725473-12341327

- ^ Levinson, Paul (November 2008), "Unburning Alexandria", Analog Science Fiction and Fact, archived from the original on 14 March 2013, retrieved 26 March 2013

- ^ Clark, Brian Charles (2006), The Plot to Save Socrates – book review, Curled Up With A Good Book, archived from the original on 7 September 2013, retrieved 26 March 2013

- ^ Inteview [sic] with Paul Levinson, Author of Unburning Alexandria, The Morton Report, 2013, archived from the original on 28 December 2019, retrieved 3 November 2013

- ^ Turchiano, Danielle (24 January 2020), "'The Good Place' Boss on Reaching the Titular Location, Finding It's a 'Bummer'", Variety, retrieved 24 January 2020

- ^ a b c Watts 2017, p. 145.

- ^ Booth 2017, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Theodore 2016, p. 182.

- ^ Watts 2017, pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b c Watts 2017, p. 146.

- ^ Booth 2017, p. 14.

- ^ a b Mark 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Archer, William (2013), The Theatrical World For 1893–1897, HardPress, ISBN 978-1-314-50827-7

- Banev, Krastu (2015), Theophilus of Alexandria and the First Origenist Controversy: Rhetoric and Power, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-872754-5

- Belenkiy, Ari (1 April 2010), "An astronomical murder?", Astronomy & Geophysics, 51 (2): 2.9 – 2.13, Bibcode:2010A&G....51b...9B, doi:10.1111/j.1468-4004.2010.51209.x

- Booth, Charlotte (2017), Hypatia: Mathematician, Philosopher, Myth, London: Fonthill Media, ISBN 978-1-78155-546-0

- Bradley, Michael John (2006), The Birth of Mathematics: Ancient Times to 1300, New York City: Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-5423-7

- Bregman, Jay (1982), Brown, Peter (ed.), Synesius of Cyrene: Philosopher-Bishop, The Transformation of the Classical Heritage, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-04192-9

- Cameron, Alan; Long, Jacqueline; Sherry, Lee (1993), Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06550-5

- Cameron, Alan (2016), "Hypatia: Life, Death, and Works", Wandering Poets and Other Essays on Late Greek Literature and Philosophy, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-026894-7

- Castner, Catherine J. (2010), "Hypatia", in Gagarin, Michael; Fantham, Elaine (eds.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, vol. 1: Academy-Bible, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, pp. 49–51, ISBN 978-0-19-538839-8

- Cohen, Martin (2008), Philosophical Tales: Being an Alternative History Revealing the Characters, the Plots, and the Hidden Scenes that Make Up the True Story of Philosophy, New York City and London: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1405140379

- Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (2017), Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History, vol. 1: Prehistory to AD 600, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-4408-4598-7

- Deakin, M. A. B. (1992), "Hypatia of Alexandria" (PDF), History of Mathematics Section, Function, 16 (1): 17–22, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022

- Deakin, Michael A. B. (1994), "Hypatia and her mathematics", American Mathematical Monthly, 101 (3): 234–243, doi:10.2307/2975600, JSTOR 2975600, MR 1264003

- Deakin, Michael A. B. (2007), Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician and Martyr, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-59102-520-7

- Deakin, Michael (2012), "Hypatia", Encyclopædia Britannica

- Dzielska, Maria (1996), Hypatia of Alexandria, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-43776-0

- Dzielska, Maria (2008), "Learned women in the Alexandrian scholarship and society of late Hellenism", in el-Abbadi, Mostafa; Fathallah, Omnia Mounir (eds.), What Happened to the Ancient Library of Alexandria?, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 129–148, ISBN 978-9004165458

- Edwards, Catharine (1999), Roman Presences: Receptions of Rome in European Culture, 1789-1945, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-59197-3

- Emmer, Michele (2012), Imagine Math: Between Culture and Mathematics, New York City: Springer, ISBN 978-8847024274

- Engels, David (2009), "Zwischen Philosophie und Religion: Weibliche Intellektuelle in Spätantike und Islam", in Groß, Dominik (ed.), Gender schafft Wissen, Wissenschaft Gender? Geschlechtsspezifische Unterscheidungen Rollenzuschreibungen im Wandel der Zeit (PDF), Kassel University Press, pp. 97–124, ISBN 978-3-89958-449-3, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022

- Haas, Christopher (1997), Alexandria in Late Antiquity: Topography and Social Conflict, Baltimore, MS and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5377-7

- Hoche, Richard (January 1860), "XV. Hypatia, die tochter Theons", Philologus (in German), 15 (1–3): 435–474, doi:10.1524/phil.1860.15.13.435, S2CID 165101471

- Knorr, Wilbur (1989), "III.11: On Hypatia of Alexandria", Studies in Ancient and Medieval Geometry, Boston: Birkhäuser, pp. 753–804, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3690-0_27, ISBN 978-0-8176-3387-5, S2CID 160209956

- Macqueen-Pope, Walter (1948), Haymarket: theatre of perfection, Allen

- Mark, Joshua J. (17 February 2014), "Historical Accuracy in the Film Agora", World History Encyclopedia

- Novak, Ralph Martin Jr. (2010), Christianity and the Roman Empire: Background Texts, Harrisburg, PA: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 239–240, ISBN 978-1-56338-347-2

- Oakes, Elizabeth H. (2007), "Hypatia", Encyclopedia of World Scientists, New York City: Infobase Publishing, p. 364, ISBN 9781438118826

- Pasachoff, Naomi; Pasachoff, Jay M. (2007), "Hypatia", in Trimble, Virginia; Williams, Thomas R.; Bracher, Katherine; Jarrell, Richard; Marché, Jordan D.; Ragep, F. Jamil (eds.), Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, New York City: Springer, ISBN 978-0387304007

- Penella, Robert J. (1984), "When was Hypatia born?", Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 33 (1): 126–128, JSTOR 4435877

- Riedweg, Christoph (2005) [2002], Pythagoras: His Life, Teachings, and Influence, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-7452-1

- Rosser, Sue Vilhauser (2008), Women, Science, and Myth: Gender Beliefs from Antiquity to the Present, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1598840957

- Theodore, Jonathan (2016), The Modern Cultural Myth of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Manchester, England: Palgrave, Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-56997-4

- Waithe, Mary Ellen (1987), Ancient Women Philosophers: 600 B.C.–500 A. D, vol. 1, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, ISBN 978-90-247-3368-2

- Walsh, Christine (2007), The Cult of St Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7546-5861-0

- Watts, Edward J. (2008) [2006], City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520258167

- Watts, Edward J. (2017), Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0190659141

- Wessel, Susan (2004), Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian Controversy: The Making of a Saint and of a Heretic, Oxford Early Christian Studies, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-926846-7

- Whitfield, Bryan J. (Summer 1995), "The Beauty of Reasoning: A Reexamination of Hypatia and Alexandria" (PDF), The Mathematics Educator, 6 (1): 14–21, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2006, retrieved 17 April 2010

Further reading

[edit]- Berggren, J. L. (February 2009), "The life and death of Hypatia", Metascience, 18 (1): 93–97, doi:10.1007/s11016-009-9256-z, S2CID 170359849

- Bernardi, Gabriella (2016), "Hypatia of Alexandria (355 or 370 c. to 415)", The Unforgotten Sisters: Female Astronomers and Scientists before Caroline Herschel, Springer Praxis Books, pp. 27–36, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-26127-0_5, ISBN 978-3319261270

- Brakke, David (2018), "Hypatia", in Torjesen, Karen; Gabra, Gawdat (eds.), Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia, Claremont Graduate University

- Cain, Kathleen (Spring 1986), "Hypatia, the Alexandrian Library, and M.L.S. (Martyr-Librarian Syndrome)", Community & Junior College Libraries, 4 (3): 35–39, doi:10.1300/J107V04N03_05

- Cameron, Alan (1990), "Isadore of Miletus and Hypatia: On the editing of mathematical texts", Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 31 (1): 103–127

- Donovan, Sandy (2008), Hypatia: Mathematician, Inventor, and Philosopher (Signature Lives: Ancient World), Compass Point Books, ISBN 978-0756537609

- Molinaro, Ursule (1990), "A Christian Martyr in Reverse: Hypatia", A Full Moon of Women: 29 Word Portraits of Notable Women From Different Times and Places + 1 Void of Course, New York City: Dutton, ISBN 978-0-525-24848-4

- Nietupski, Nancy (1993), "Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician, astronomer and philosopher", Alexandria, 2, Phanes Press: 45–56, ISBN 978-0933999978. See also The Life of Hypatia from The Suda (Jeremiah Reedy, trans.), pp. 57–58, The Life of Hypatia by Socrates Scholasticus from his Ecclesiastical History 7.13, pp. 59–60, and The Life of Hypatia by John, Bishop of Nikiu, from his Chronicle 84.87–103, pp. 61–63.

- Parsons, Reuben (1892), "St. Cyril of Alexandria and the Murder of Hypatia", Some Lies and Errors of History, Notre Dame, IN: Office of the "Ave Maria", pp. 44–53

- Richeson, A. W. (1940), "Hypatia of Alexandria" (PDF), National Mathematics Magazine, 15 (2): 74–82, doi:10.2307/3028426, JSTOR 3028426

- Rist, J. M. (1965), "Hypatia", Phoenix, 19 (3): 214–225, doi:10.2307/1086284, JSTOR 1086284

- Ronchey, Silvia (2021) [2011], Hypatia: The True Story, Berlin-New York: DeGruyter, ISBN 978-3-1107-1757-0

- Schaefer, Francis (1902), "St. Cyril of Alexandria and the Murder of Hypatia", The Catholic University Bulletin, 8: 441–453.

- Teruel, Pedro Jesús (2011), Filosofía y Ciencia en Hipatia (in Spanish), Madrid: Gredos, ISBN 978-84-249-1939-9

- Vogt, Kari (1993), "'The Hierophant of Philosophy' – Hypatia of Alexandria", in Børresen, Kari Elisabeth; Vogt, Kari (eds.), Women's Studies of the Christian and Islamic Traditions: Ancient, Medieval and Renaissance Foremothers, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 155–175, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1664-0_3, ISBN 978-9401116640

- Zielinski, Sarah (14 March 2010), "Hypatia, Alexandria's Great Female Scholar", Smithsonian, archived from the original on 4 January 2014, retrieved 28 May 2010

External links

[edit]- International Society for Neoplatonic Studies

- Socrates of Constantinople, Ecclesiastical History, VII.15, at the Internet Archive

- (in Greek and Latin) Socrates of Constantinople, Ecclesiastical History, VII.15 (pp. 760–761), at the Documenta Catholica Omnia

Hypatia

View on GrokipediaHypatia of Alexandria (Greek: Ὑπατία; c. 370 – 415 AD) was a Neoplatonist philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer active in Alexandria, Egypt, during the late Roman Empire.[1] Born as the daughter of the mathematician Theon of Alexandria, she received an elite education in mathematics and philosophy, eventually succeeding her father as head of the Neoplatonic school at the Musaeum, where she lectured publicly on Platonic philosophy, Ptolemaic astronomy, and Euclidean geometry to diverse students, including the future bishop Synesius of Cyrene.[2][3] Her known scholarly contributions include editing and commenting on classical texts such as Ptolemy's Almagest in collaboration with her father and revising Theon's commentary on Euclid's Elements, efforts that helped preserve Hellenistic mathematical traditions amid cultural transitions.[4] Hypatia maintained a reputation for intellectual rigor, personal virtue, and independence, rejecting marriage to focus on teaching, while her advisory role to the Roman prefect Orestes placed her at the center of political conflicts with Christian authorities, particularly Bishop Cyril of Alexandria.[5] These tensions escalated into her brutal murder in March 415 AD by a mob of Christian zealots, who reportedly dragged her from her chariot, stripped and flayed her with roof tiles, and burned her remains— an event chronicled by the historian Socrates Scholasticus as stemming from envy of her influence rather than doctrinal opposition alone.[6][7]

Early Life

Family Background and Education

Hypatia was the daughter of Theon of Alexandria, a mathematician and astronomer active in the late 4th century CE, who served as a scholar at the Mouseion, the intellectual center of Alexandria modeled after the earlier Library of Alexandria.[5] Theon is known for his editions and commentaries on works by Euclid, Ptolemy, and other mathematicians, including a recension of Euclid's Elements that became the standard medieval version.[8] No contemporary records detail Hypatia's mother or siblings, and ancient sources focus exclusively on Theon's paternal role in her upbringing, suggesting he raised her amid Alexandria's scholarly environment without mention of other family influences.[9] Her birth date is uncertain, with scholarly estimates ranging from c. 350 CE to c. 370 CE, based on indirect references in late antique sources like the Suda lexicon and calculations tied to her father's lifespan and her own reported age at death in 415 CE.[10] Theon educated Hypatia intensively in mathematics and astronomy from childhood, immersing her in the technical traditions of Hellenistic scholarship preserved at the Mouseion; ancient accounts, including those in the Suda, state that she not only mastered these fields under his guidance but advanced beyond his own expertise, contributing commentaries that elucidated complex geometrical proofs.[5][4] This paternal instruction extended to philosophy, where Hypatia engaged with Neoplatonism, drawing on Plotinus and his successors, though primary evidence for her early philosophical training remains tied to Theon's scholarly circle rather than formal Athenian or external study; no records indicate travel outside Alexandria for education.[9] Theon's approach emphasized practical mastery of Ptolemaic astronomy and Euclidean geometry, equipping Hypatia with skills in computation and instrumentation that later defined her teaching, as evidenced by surviving fragments of his works she likely assisted in editing.[8]Intellectual Formation in Alexandria

Hypatia was educated entirely in Alexandria by her father, Theon of Alexandria, a mathematician and astronomer who produced commentaries on Ptolemy's Almagest and Euclid's Elements.[10] Theon, possibly the last known member of the Musaeum's scholarly community, provided rigorous instruction in mathematics, astronomy, and related disciplines, fostering her development into a scholar who eventually surpassed his own attainments in these fields.[11] [10] Contemporary accounts indicate that Theon emphasized comprehensive training, including exposure to rhetoric and comparative religion, to cultivate Hypatia's intellectual versatility and persuasive abilities.[2] Under his guidance, she mastered advanced Platonic philosophy, likely drawing from the Neoplatonic traditions prevalent in Alexandrian intellectual circles, though no specific teachers beyond Theon are documented.[5] By the early fifth century, around 400 AD, Hypatia had assumed leadership of the Platonist school, reflecting the culmination of her formative studies.[10] Primary historical sources, such as the sixth-century historian Damascius, portray Theon's educational approach as deliberately intensive, aimed at enabling Hypatia to excel beyond typical scholarly limits of the era.[11] This upbringing in Alexandria's declining but still vibrant pagan intellectual milieu equipped her with the expertise to later edit and comment on key mathematical texts, including works on conic sections and astronomical tables.[12]Professional Career

Teaching and Lectures

Hypatia succeeded her father, Theon of Alexandria, as head of the Neoplatonic school in Alexandria around the late 4th century, where she delivered public lectures on mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy.[5] Her sessions drew crowds seeking guidance on complex problems, as contemporary accounts describe audiences consulting her as an oracle for solutions in sciences and letters.[5] She expounded works by Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, and earlier mathematicians, emphasizing logical demonstration and rhetorical clarity to make abstract concepts accessible.[12] In her lectures on technical subjects, Hypatia employed practical methods such as geometric diagrams traced with a staff on the ground or in dust, facilitating visualization of conic sections and astronomical phenomena.[12] Synesius of Cyrene, in his surviving letters, addressed her as a revered teacher and sought her expertise on instruments like the astrolabe and hydroscope, indicating her role in instructing on applied astronomy and mechanics.[13] Her approach integrated Neoplatonic metaphysics with empirical tools, prioritizing first-hand reasoning over rote memorization, though primary evidence remains limited to fragmented epistolary and ecclesiastical records.[14]Notable Students and Disciples