Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Champasak province

View on WikipediaThis article is written like a travel guide. (March 2020) |

Key Information

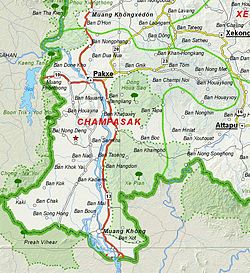

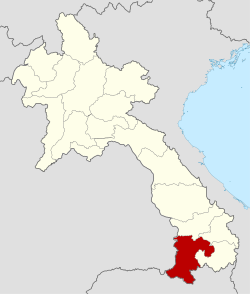

Champasak (or Champassak, Champasack – Lao: ຈຳປາສັກ [t͡ɕàm pàː sák]) is a province in southwestern Laos, near the borders with Thailand and Cambodia. It is 1 of the 3 principalities that succeeded the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang. As of the 2015 census, it had a population of 694,023. The capital is Pakse, and the province takes its name from Champasak, the former capital of the Kingdom of Champasak.

Champasak is bordered by Salavan province to the north, Sekong province to the northeast, Attapeu province to the east, Cambodia to the south, and Thailand to the west. The Mekong River forms part of the border with neighboring Thailand and contains Si Phan Don ('Four Thousand Islands') in the south of the province, on the border with Cambodia.

Champasak has played a role in the history of Siam and Laos, with battles taking place in and around Champasak.[2] Its cultural heritage includes temple ruins and French colonial architecture. Champasak has some 20 wats (temples), such as Wat Phou, Wat Luang, and Wat Tham Fai. Freshwater dolphins and the province's waterfalls are tourist attractions.[2]

Geography

[edit]Champasak province covers an area of 15,415 km2 (5,952 sq mi).[3] The Mekong forms part of the border with neighboring Thailand and, after a bend projecting westward, turns east and flows southeasterly through the province down to Cambodia. Champasak can be reached from Thailand through Sirindhorn District's Chong Mek border crossing, to Vang Tao on the Lao side, from where the highway leads east towards the provincial capital, Pakse. The capital is on a highway, Route 13, and the French legacy can be seen in the city's architecture.[2][4]

Si Phan Don (Four Thousand Islands) is on a stretch of the Mekong north of the border with Cambodia. Of these islands, Don Khong is the largest and has a number of villages, temples, and caves. A French-built bridge on the abandoned railway line provides the link with two smaller islands, Don Det and Don Khon.[2]

There are waterfalls in the province such as the Tad Somphamit (or Liphi) Waterfall, at Don Khon to the west of Ban Khon village. Below the falls in the calmer waters of the Mekong the fresh water dolphins can be seen. The Khone Phapheng Falls to the east of Don Khon, also on the Mekong, cascade along a broad mouth of rock slopes in a curvilinear pattern. The 120 m (390 ft) Tad Fane Waterfall (or Dong Hua Sao) in the Bolaven Plateau is the country's highest waterfall. It is created by the Champi and Prakkoot streams which originate at about 1,000 m (3,300 ft) above sea level.[2] The plateau is east of Pakse.[5]

-

Si Phan Don

-

Liphi Waterfall

-

Khone Phapheng Falls

Protected areas

[edit]Xe Pian National Biodiversity Conservation Area (NBCA) lies in the southeastern part of the province, while the Dong Hua Sao National Protected Area is in the eastern area.[6] The Center for Protection and Conservation of freshwater dolphins is on the Cambodian border. These freshwater dolphins are known locally as pakha in Lao, and are found on this particular stretch of the Mekong River. Hire boats are available to see these dolphins, either from Ban Khon or Ban Veunkham (at the southern end of the islands).[2]

The Mekong Channel from Phou Xiang Thong to Siphandon Important Bird Area (IBA) is 34,200 ha (85,000 acres) in size. A portion of the IBA (10,000 hectares) overlaps with the 120,000 ha (300,000 acres) Phou Xieng Thong National Protected Area. The IBA encompasses 2 provinces, Champasak and Salavan. The IBA is at an elevation of 40–50 m (130–160 ft). Its topography consists of earth banks, rocky banks, rocky islands, sandbars, low vegetated islands, rocky islets, and sandy beaches. Avifauna include nesting little terns, river lapwings, river terns, small pratincoles and wire-tailed swallows.[7]

The 36,650 ha (90,600 acres) Phou Xiang Thong IBA is in the Phou Xiengthong NBCA. This IBA spans 2 provinces, Champasak and Salavan. The IBA is at an elevation of 40–500 m (130–1,640 ft). The topography consists of low hills, lowlands, rivers, and seasonal streams. Habitat is characterized by dry deciduous tropical forest, moist deciduous tropical forest, semi-evergreen tropical rainforest, mixed deciduous forest, dry dipterocarp forest, and open rocky savanna. Notable avifauna include the grey-faced tit-babbler, green peafowl, red-collared woodpecker, and Siamese fireback.[8]

Administrative divisions

[edit]The province is made up of the following districts:[2][9]

| Map | Code | Name | Lao script |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 16-01 | Pakse District | ເມືອງປາກເຊ | |

| 16-02 | Sanasomboun District | ເມືອງຊະນະສົມບູນ | |

| 16-03 | Batiengchaleunsouk District | ເມືອງບາຈຽງຈະເລີນສຸກ | |

| 16-04 | Paksong District | ເມືອງປາກຊ່ອງ | |

| 16-05 | Pathouphone District | ເມືອງປະທຸມພອນ | |

| 16-06 | Phonthong District | ເມືອງໂພນທອງ | |

| 16-07 | Champassack District | ເມືອງຈຳປາສັກ | |

| 16-08 | Soukhoumma District | ເມືອງສຸຂຸມາ | |

| 16-09 | Mounlapamok District | ເມືອງມູນລະປະໂມກ | |

| 16-10 | Khong District | ເມືອງໂຂງ |

Demographics

[edit]The population of the province, from the 2015 census, is 694,023.[10] The ethnic composition consists mainly of Lao,[2] and also Chieng, Inthi, Kaseng, Katang, Kate, Katu, Kien Lavai, Laven, Nge, Nyaheun, Oung, Salao, Suay, Tahang, and Tahoy ethnic groups, and Khmer. Near the border between Thailand and Cambodia there is an Chams ethnic group known as the Laotian Chams.[4]

Economy

[edit]The economic output of the province consists primarily of agricultural products—especially production of coffee, tea, and rattan. It is “one of the most important coffee producing areas of Laos” along with Salavan and Sekong provinces.[11] Pakse is the main trade and travel link with Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam.[2] Following the building of the Lao Nippon bridge across the Mekong at Pakse in 2002, trade with Thailand has multiplied several fold. The bridge lies at the junction of roads to the Bolaven Plateau in the east, Thailand in the west, and Si Phan Don to the south. Improved infrastructure has led to an increase in tourism since the 1990s.[12] The weaving centres of Ban Saphai and Don Kho are 18 km (11 mi) from Pakse.[13] The Jhai Coffee Farmers Cooperative, headquartered at the provincial capital, operates on the Bolaven Plateau.[14] The Bolaven Plateau has rubber, tobacco, peaches, pineapple, and rice production.[5]

-

Pakse market

-

The Lao Nippon bridge

-

Coffee drying on the Bolaven Plateau

-

Lao family on a 'Chinese water buffalo' in Champasak province

Landmarks

[edit]Champasak has some 20 wats (temples). The Khmer ruins of Wat Phou are in the capital of the Champasak District.[13] They are on the Phu Kao mountain slopes, about 6 km (3.7 mi) from Champasak District and about 45 km (28 mi) to the south of Pakse along the Mekong River. Wat Phou was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site on 14 December 2001. It is the second such site in Laos. The temple complex, built in the Khmer style, overlooks the Mekong River and was a Hindu temple in the Khmer Empire. At the same location are the ruins of other pre-Angkor monuments.[2] Wat Phou Asa is a Hindu-Khmer pagoda, built on flat rock on Phou Kao Klat Ngong Mount in Pathoumphone District. It can be reached via Route 13, south of Pakse, and then by foot from Ban Klat Ngong. The pagoda was built by the Khmers and is in a ruined state. It is under renovation.[2] Wat Luang and Wat Tham Fai were built in 1935. There is a monastic school and a Buddha foot imprint shrine in Wat Pha Bhat and Wat Tham Fai; religious festivals are held within an open area.[13]

Tormor Rocky Channel is the 15th National Heritage Site in Laos; it is about 11 km (6.8 mi) southeast of Wat Phou Champasak on the left bank of the Mekong. The pathway to the building is lined with columns of sandstone. There is a chamber with doors in the front and rear and windows on 2 sides. Inscriptions imply the site is related to Wat Phou Champasak.[2] An archeological site is at Pu Asa on a mountain top.[4] Kiat Ngong village is noted for its medicinal plants and forest products.[4]

The Champasak Historical Heritage Museum in Pakse provides insight into the history of Laos and its cultural and artistic heritage. In Wat Amath, treasures dating back to the Stone Age can be seen.[2] The museum has artifacts, documents, 3 Dong Son bronze drums, 7th century lintels made of sandstone, textile and jewelry collections including items such as iron ankle bracelets, ivory ear plugs, musical instruments, a stele in Thai script (15th to 18th century), a water jar of 11th or 12th century vintage, a Shiva linga, a model of Wat Phu Champasak, Buddha images, and American weaponry.[13] The province was the site of Laos's first railway, the Don Det – Don Khon narrow gauge railway on Don Det and Don Khon Islands.[2]

-

View from near the top of Wat Phou

-

Wat Luang in Pakse

-

Wat Tham Fai in Pakse

Culture

[edit]During the third lunar month (February), celebrations at Angkor precede Champasack's traditional Wat Phou Festival at the site of ruins. The festival is noted for elephant racing, cockfighting, and cultural performances of traditional Lao music and dance.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2025-02-07.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Destination: Champasack Province Destination". Laos Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ "Champasack Province". Lao Tourism. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d The Lao National Tourism Administration. "Champassak Province". Ecotourism Laos. GMS Sustainable Tourism Development Project in Lao PDR. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ a b Mansfield & Koh 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Mekong Channel from Phou Xiang Thong to Siphandon". BirdLife International. 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Phou Xiang Thong". BirdLife International. 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Provinces of Laos". Statoids.com. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ "Results of Population and Housing Census 2015" (PDF). Lao Statistics Bureau. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Lao People's Democratic Republic: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (EPub). International Monetary Fund. 21 October 2008. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4527-9182-1. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Pakse; Information & Statistics". Travel-Tourist-Information-Guide.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2014-12-08.

- ^ a b c d Burke & Vaisutis 2007, p. 255-56.

- ^ Bush, Elliot & Ray 2010, p. 12.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burke, Andrew; Vaisutis, Justine (2007). Laos 6th Edition. Lonely Planet. pp. 255–56. ISBN 9781741045680.

- Bush, Austin; Elliot, Mark; Ray, Nick (1 December 2010). Laos 7. Lonely Planet. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-74179-153-2.

- Mansfield, Stephen; Koh, Magdalene (1 September 2008). Laos. Marshall Cavendish. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7614-3035-3.

External links

[edit]Champasak province

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Borders

Champasak Province is situated in the southwestern region of Laos, with its approximate central coordinates at 15°00′N 106°00′E. This positioning places it in a key part of the country, encompassing diverse landscapes from riverine lowlands to elevated plateaus. The province spans a total area of 15,415 square kilometers, ranking it among the larger administrative divisions in Laos by land coverage.[2][5] To the north, Champasak borders Salavan Province, while Sekong Province lies to the northeast and Attapeu Province to the east. In the south, it shares an international boundary with Cambodia, specifically the provinces of Stung Treng and Preah Vihear. The western border follows the Mekong River, adjoining Thailand's Ubon Ratchathani province, which facilitates cross-border interactions and defines much of the province's hydrological and economic orientation.[6][7] The province's strategic location along the Mekong River has long shaped its role in regional dynamics, serving as a corridor for historical trade routes and human migration between Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia. This riverside positioning not only supports vital transportation links but also underscores Champasak's importance as a cultural and economic bridge in Southeast Asia.[2]Topography and Climate

Champasak Province features a diverse topography that encompasses the elevated Bolaven Plateau in the northeast, expansive lowland plains along the Mekong River in the west, and forested highlands in the central and southern regions. The Bolaven Plateau, spanning approximately 6,000 km² primarily within the province, rises to elevations between 1,000 and 1,350 meters above sea level and consists of low-relief terrain shaped by ancient volcanic activity. These volcanic origins have resulted in fertile basaltic soils derived from lavas dating from about 16 million years ago to less than 40,000 years ago, supporting agricultural activities such as coffee cultivation.[8] The province's river systems are dominated by the Mekong River, which forms its western border with Thailand for much of its length, providing a vital waterway for transportation and sediment deposition in the adjacent lowlands. Major tributaries, including the Xe Pian River, originate from the Bolaven Plateau and flow southeastward, contributing to irrigation for rice paddies and supporting wetland ecosystems before joining the Mekong. Geological features include volcanic scoria cones and shallow craters on the plateau, numbering nearly 100, alongside lava flows that extend up to 50 km in length. In the southern areas, particularly around the Siphandon (Four Thousand Islands) region in the Mekong Valley, limestone formations give rise to karst topography, though these are less extensive compared to northern Laos.[9][10][8][11] Champasak experiences a tropical monsoon climate characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons. The wet season, from May to October, brings heavy rainfall averaging 1,500 to 2,000 mm annually in the lowlands, with even higher amounts up to 4,100 mm on the Bolaven Plateau due to its elevation. Temperatures during this period typically range from 25°C to 31°C. The dry season, spanning November to April, features lower precipitation and warmer conditions, with average temperatures between 25°C and 35°C in the lowlands; the plateau remains cooler, averaging 15°C to 25°C year-round, which moderates the overall provincial climate variability.[12][13][14]Protected Areas

Champasak province hosts several key national protected areas that safeguard its rich biodiversity and ecosystems, covering approximately 30% of the province's total land area of 15,415 km². These zones, established under Laos's National Biodiversity Conservation Areas (NBCAs) system, play a crucial role in preserving endangered species, maintaining watersheds, and supporting regional ecological connectivity.[15] The Xe Pian National Biodiversity Conservation Area (NBCA), spanning 2,100 km² in the southeastern part of the province, was established in 1993 to protect lowland forests and wetlands along the Mekong River basin.[16] It harbors endangered species such as Asian elephants (Elephas maximus), tigers (Panthera tigris), and Siamese crocodiles (Crocodylus siamensis), alongside diverse avifauna and aquatic habitats that support migratory birds and fish populations.[17][16] Conservation efforts here include participatory biodiversity assessments and wetland management plans, particularly for the adjacent Beung Kiat Ngong Ramsar site.[18] Dong Hua Sao National Protected Area, covering 1,100 km² in the central-eastern region, serves as a critical buffer for the Bolaven Plateau's upland ecosystems with its dense semi-evergreen rainforests.[19] The area is renowned for its botanical diversity, including rare orchid species and tropical hardwoods, as well as avian populations featuring hornbills, kingfishers, and barbets.[20] Established in 1993, it protects against deforestation while fostering habitat for medium-sized mammals like leopards and civets.[21][22] Phou Xieng Thong National Protected Area, encompassing about 1,200 km² primarily in mountainous terrain shared with Salavan province, emphasizes watershed protection and cultural landscapes integrated with ethnic minority communities.[23] Ranging from 300 to 1,500 meters in elevation, it features karst formations, wild orchids, and habitats for large mammals, while over 30 villages of Alak, Laven, and other groups rely on sustainable resource use within its boundaries.[24][25] Designated in 1993, the area contributes to upstream water regulation for the Mekong tributaries.[23] Despite these protections, the province's protected areas face significant threats from illegal logging, poaching, and agricultural encroachment, which have reduced forest cover and wildlife populations.[26] Ongoing conservation initiatives, including UNESCO-supported Ramsar wetland management and WWF-led biodiversity monitoring, aim to address these challenges through community involvement and transboundary cooperation.[27][28]History

Ancient and Khmer Periods

The region encompassing modern Champasak province formed part of the Funan Kingdom, an early Indianized state that flourished from the 1st to 6th centuries CE, with its influence extending along the Mekong River trade routes into southern Laos.[29] Archaeological evidence, such as the 5th-century Wat Luang Kau stele (K. 365) near Wat Phou, indicates Funan's cultural and economic reach, facilitating exchanges of goods and ideas through the Mekong valley.[29] This period marked the introduction of Hindu influences, setting the stage for later developments in the area. By the 6th century CE, Champasak integrated into the Chenla Kingdom, which succeeded Funan and dominated from the 6th to 9th centuries, with the region serving as a key southern territory.[30] Archaeological findings, including the mid-5th-century Devānīka stele and the 590 CE Mahendravarman inscriptions, suggest Champasak as Chenla's initial capital, highlighting a transitional phase from Funan rule.[30] Evidence of Hindu-Buddhist temples abounds, such as the 6th-century pre-Angkorian structure at Houay Sa Houa 2, featuring elaborate foundations and Nandin pedestals, alongside 7th-century stupas at Nong Vienne that reflect coexisting Hindu Shivaite shrines and early Buddhist elements.[30] From the 9th to 13th centuries CE, Champasak functioned as an outpost of the Khmer Empire, centered at Angkor, with significant pre-Angkorian development at sites like Wat Phou, constructed between the 5th and 12th centuries and dedicated to Shiva.[4] The complex, integrated into a sacred landscape along the Mekong, exemplifies Khmer architectural and spiritual expansion, with construction intensifying under kings like Yasovarman I in the early 10th century.[31] The Vat Phou complex holds profound archaeological significance as a precursor to UNESCO World Heritage designation in 2001, preserving over 1,000 years of planned landscape featuring linga stones symbolizing Shiva and baray reservoirs for ritual water management.[4] These elements, spanning a 10 km axis from Phou Kao mountain to the Mekong, underscore the site's role in Hindu cosmology and its enduring testament to Khmer ingenuity in harmonizing nature and divinity.[4]Kingdom of Champasak

The Kingdom of Champasak emerged in 1713 amid the fragmentation of the Lan Xang kingdom, when Chao Soisysamouth—also known as Nokasad and a grandson of the last Lan Xang king, Sourigna Vongsa—ascended as its first ruler with support from the influential monk Phra Khrou Phonsamek and the noblewoman Nang Phao.[32] The capital was established at Champasak town, marking the polity's recognition as an independent Lao kingdom in southern Laos.[32] This formation reflected broader regional instability following Lan Xang's collapse in the late 17th century, as local leaders sought to consolidate power in the Mekong River basin. Successive rulers navigated a precarious balance of autonomy and external pressures, particularly from Siam (modern Thailand). Nokasad reigned from 1713 to 1737 without paying tribute to external powers, laying the foundation for the dynasty.[32] His son, Chao Sayakoumane (Sayakoune), ruled from 1737 to 1791 and resisted Siamese incursions during the 1770s, though the kingdom ultimately became a Siamese vassal in 1778 following military intervention by King Taksin of Thonburi.[32][33] In the early 19th century, alliances formed amid regional tensions, including ties to Chao Anou of Vientiane during his rebellion against Siam. The last independent king, Chao Khamsouk (often referred to in variants as Nay Nakone), ruled until 1904, overseeing the final phase before French colonial absorption.[32][33] The kingdom's territory encompassed southern Laos from the Mekong River's left bank to the Cambodian border, serving as a buffer between Siamese and Vietnamese influences while maintaining nominal vassal relations with Siam after 1778, which involved periodic tribute payments.[32] Its economy centered on Mekong River trade in goods such as forest products, rice, and lacquer, supplemented by tribute extraction from local populations and, under Siamese oversight, labor levies including slave trade in areas like Attapeu.[32][33] This riverine commerce facilitated cultural and economic exchanges but also exposed the kingdom to exploitation by overlords. The kingdom's decline accelerated with Siamese conquests during the Lao Rebellion of 1827–1828, which crushed resistance in Vientiane and integrated Champasak more tightly into the Siamese administrative system, eroding its autonomy through direct control and resource extraction.[32] Rebellions, such as those led by Ai Chiangkaew in 1791 and others against Siamese rule, highlighted ongoing unrest tied to heavy tributes and cultural impositions like the introduction of the Dhammayuttika Nikaya sect in 1851.[33] Legends surrounding the dynasty often invoke family tragedies and a prophecy that reuniting dispersed sacred Buddhist images—such as the Phra Kaeo Phaluek Mok—could restore its power, reflecting beliefs in spiritual causation for the realm's misfortunes.[32]Colonial and Modern Eras

In 1904, the Kingdom of Champasak was formally dissolved under a treaty with France, marking the end of its independent status as the territory was integrated into the newly formed French protectorate of Laos within French Indochina.[34][35] The French colonial administration reorganized the region, establishing Pakse as the primary administrative center for southern Laos to facilitate governance and resource extraction from the Mekong River basin.[36] During this period, Champasak's lands were administered as part of a unified Laos, with French officials overseeing taxation, infrastructure like roads, and suppression of local autonomy movements until the protectorate's duration from 1904 to 1953.[37] World War II disrupted French control when Japanese forces launched a coup and occupied Laos in March 1945, ending Vichy French administration, interning colonial officials, and exploiting local resources for the imperial war effort, including in Champasak.[38] In the war's aftermath, the Lao Issara movement emerged in 1945, advocating for full independence from foreign rule and briefly establishing a provisional government that sought to unify Lao territories, including Champasak, under national authority.[39] French forces reasserted control by 1946, but mounting nationalist pressures culminated in the Franco-Lao Treaty of 1953, granting Laos sovereignty and dissolving the protectorate, with Champasak formally incorporated as a province in the Kingdom of Laos.[37] Following the 1975 communist victory, Champasak was restructured as a province within the newly established Lao People's Democratic Republic, aligning the region with socialist policies and central planning from Vientiane.[40] The Vietnam War's spillover effects severely impacted eastern Champasak, where U.S. bombing campaigns from 1964 to 1973 targeted supply routes along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, dropping over 2 million tons of ordnance and leaving extensive unexploded remnants that continue to contaminate agricultural lands and pose hazards.[41] These bombings, part of covert operations like Barrel Roll, devastated rural communities and infrastructure in the province's eastern districts.[42] The adoption of the New Economic Mechanism in 1986 initiated market-oriented reforms that extended into the 1990s, liberalizing trade and investment to stimulate sectors like tourism in Champasak, where heritage sites and natural attractions began drawing regional visitors.[43] In the 2020s, tourism has surged, with Champasak welcoming 426,000 visitors in the first seven months of 2025 alone, including over 73,000 border crossers via Mekong River points from Thailand and Cambodia, supporting projections of national totals exceeding 4.3 million arrivals by year-end.[44][45] This growth, driven by eased visa policies and cross-border initiatives, has boosted local economies while highlighting ongoing challenges like unexploded ordnance clearance.[46]Government and Administration

Administrative Divisions

Champasak Province is administratively divided into 10 districts, each governed by a district chief under the oversight of the provincial authority. These districts serve as the primary units for local administration, resource management, and development initiatives, encompassing a total provincial area of 15,415 km² and a population of approximately 704,000 as of 2024.[2] The districts vary in size, population, and function, with some focusing on urban administration and others on rural agriculture or tourism. For instance, Pakse District functions as the capital and primary urban hub, handling commercial activities and serving as the gateway to the province. In contrast, Khong District is notable for encompassing the Si Phan Don (Four Thousand Islands) region along the Mekong River, making it a key area for ecotourism and riverine livelihoods.[2] The districts are:| District Name |

|---|

| Bachiangchaleunsook |

| Champasak |

| Khong |

| Mounlapamok |

| Pakse |

| Pakxong |

| Pathoumphone |

| Phonthong |

| Sanamxay |

| Sukhuma |

Capital and Local Governance

The capital of Champasak Province is Pakse (also spelled Pakxe), a city located at the confluence of the Mekong and Xe Don Rivers that serves as the provincial administrative, economic, and transportation hub. With an urban population of approximately 120,000, Pakse functions as the primary center for government services, commerce, and regional connectivity in southern Laos.[48] The city was established in 1905 as an administrative outpost by French colonial authorities during the period of French Indochina, evolving from a small trading post into a key governance node.[49] Champasak Province's local governance operates within the unitary structure of the Lao People's Democratic Republic, where the provincial governor is appointed by the Prime Minister and can be transferred or removed based on national priorities, ensuring alignment with central directives.[50] The Provincial People's Assembly, introduced in 2016 as part of decentralization reforms, advises on local policies and supervises administrative implementation, with members elected to represent provincial interests while adhering to national laws.[51] This assembly integrates with the broader national framework through the Law on Local Administration of 2015, which defines provincial roles in planning, budgeting, and service delivery under central oversight.[52] In March 2025, constitutional amendments were approved, granting expanded powers to local administrations to promote economic autonomy and strengthen decentralization.[53] Local policies emphasize sustainable development, including the national 9th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan (2021–2025), which prioritizes green growth and poverty eradication in Champasak through targeted rural initiatives. For instance, the Laos Tourism Development Plan (2021–2025) highlights Champasak's eco-cultural assets, such as Vat Phou and the 4,000 Islands, to foster community-based tourism while promoting environmental preservation and economic inclusion.[54] Poverty reduction efforts focus on rural districts via village development funds and infrastructure improvements, aiming to eradicate basic poverty by enhancing access to services and markets in line with national strategies.[55] A key institution supporting education and research is Champasak University, located in Pakse and established in 2002 as the province's primary higher education center, offering programs that contribute to local capacity building in fields like agriculture, tourism, and environmental management.[56]Demographics

Population Statistics

According to the 2015 Population and Housing Census conducted by the Lao Statistics Bureau, Champasak Province had a total population of 694,023 residents.[57] This figure reflects the official enumerated count, adjusted for underenumeration in subsequent analyses. By 2020, projections based on census data estimated the population at 752,688, indicating an average annual growth rate of approximately 1.4% between 2015 and 2020.[58] The growth has been attributed to natural increase, internal migration, and emerging opportunities in sectors like tourism.[59] The province's population density stood at about 45 people per square kilometer in 2015, based on its land area of 15,415 square kilometers, rising to approximately 49 people per square kilometer by 2020.[57][58] Urbanization patterns show a relatively low level of urban development, with 26% of the population (180,443 people) residing in urban areas in 2015, primarily concentrated in the capital, Pakse, while 74% lived in rural settings.[57] This urban-rural split underscores Champasak's predominantly agrarian character, though urban growth in Pakse has accelerated due to its role as a regional hub.[58] Population projections suggest the total will reach approximately 800,000 by mid-2025, continuing the trend of steady expansion at around 1.4% annually, influenced by inbound migration for tourism-related employment and improved infrastructure.[58][60] Demographically, the province exhibits a balanced gender ratio of nearly 50:50, with 345,216 males and 348,807 females recorded in 2015.[57] The age structure features a youth bulge, with nearly 38% of the population under 15 years old in 2015 and a median age of approximately 23 years, reflecting broader national patterns of a young workforce.[57][61]| Year | Total Population | Annual Growth Rate (approx.) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 694,023 | - | Lao Statistics Bureau Census[57] |

| 2020 | 752,688 | 1.4% (2015-2020 average) | Projection based on census[58] |

| 2025 | ~800,000 | 1.4% (projected) | Mid-year projection[60] |

Ethnic Composition

Champasak province features a diverse ethnic composition, dominated by the Lao-Lum, or lowland Lao, who form the majority of the population. This group primarily inhabits the Mekong River lowlands, practices Theravada Buddhism, and maintains social structures centered on extended family units and village hierarchies led by elders.[3][62] Mon-Khmer ethnic minorities, such as the Katang, Alak, and Ta'oi, are classified under the Lao-Theung category and reside mainly in upland areas like the Bolaven Plateau. These groups traditionally engage in slash-and-burn agriculture and organize socially around matrilineal clans and communal longhouse villages, with rituals emphasizing animist beliefs alongside increasing Theravada influences. Katuic subgroups, including the Kaseng, are also prominent among these communities.[3][62][63][64] Smaller minorities include the Khmer, reflecting historical ties to the Cambodian border through patrilineal family structures and shared cultural heritage. Vietnamese and Chinese communities, concentrated in urban Pakse, form distinct merchant-oriented social networks.[3][65][66] Lao serves as the official language, facilitating administration and education, while ethnic dialects from the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic family are spoken within minority communities. Province-wide literacy stands at approximately 85%, supported by national education initiatives that promote multilingual instruction to bridge ethnic divides.[57]Economy

Agriculture and Natural Resources

Champasak province's agriculture is dominated by cash crops on the Bolaven Plateau, where coffee cultivation plays a central role. The plateau's volcanic soils and elevation support Arabica varieties, which constitute about 80% of Laos's coffee plantations, with Champasak accounting for over 51,000 hectares of production and contributing the majority of the nation's output through districts like Paksong.[67][68] Rice remains the staple in the Mekong lowlands, with annual production in the province supporting local self-sufficiency and surplus for export, though exact figures vary due to seasonal flooding and irrigation improvements. Other key crops include rubber, tea, and cardamom, which are intercropped or grown alongside coffee to diversify income for smallholder farmers.[69][70] Livestock rearing, primarily cattle and pigs, supplements agricultural livelihoods, with traditional free-range systems prevalent among rural households. Cattle serve as a form of savings and draft power, while pigs are raised for local consumption and sale. Fishing in the Mekong River and its tributaries provides an additional protein source, supporting food security for communities in districts like Khong and Sanamxay.[71][72][73] Natural resources in Champasak include timber from production forests, managed under national sustainable logging quotas that limit extraction volumes based on provincial assessments to prevent overharvesting. Rattan harvesting is also regulated, with community-based quotas enabling certified sustainable supply chains.[74][75] Aquaculture is emerging as a resource, exemplified by the Mekong River basa fish industrial park in Khong District, which exported its first batch to China in April 2025.[76] Hydropower development harnesses the province's rivers, exemplified by the Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy project, a 410 MW facility that became operational in December 2019 after reconstruction following a 2018 collapse, exporting electricity primarily to Thailand.[77] Agricultural challenges in Champasak are exacerbated by soil erosion on the Bolaven Plateau, where intensive coffee farming on slopes leads to degradation without adequate agroforestry practices like shade tree integration. Climate variability, including increased precipitation and temperature rises projected at +175 mm/year and +2.5°C annually, further impacts yields through erratic rainfall, flooding in lowlands, and droughts affecting upland crops. Efforts to mitigate these include promoting resilient farming models, though smallholders face barriers in adopting them due to limited access to inputs and extension services.[78][79][80]Tourism and Trade

Tourism plays a pivotal role in Champasak province's service-based economy, attracting visitors through its emphasis on ecotourism and cultural heritage. In 2024, the province contributed to Laos' national record of over 4.1 million international tourist arrivals, with provincial figures reflecting a strong recovery from the COVID-19 downturn. By the first seven months of 2025, Champasak had welcomed 426,000 visitors, including domestic, border, and international travelers, signaling robust growth. Projections for 2025 indicate the province could exceed 600,000 arrivals, supported by national targets aiming for 4.3 million visitors overall.[81][44][82] Key attractions driving this influx include the UNESCO World Heritage-listed Vat Phou temple complex, a pre-Angkorian site exemplifying ancient Khmer architecture, and the Si Phan Don archipelago, known as the 4,000 Islands, which offers serene riverine ecotourism experiences amid biodiverse Mekong ecosystems. The post-COVID rebound has been accelerated by mutual visa exemptions between Laos and Thailand, facilitating easy overland access for Thai tourists, who represent the fastest-recovering market and a major share of regional visitors. Tourism revenue in the province reached over $55 million in the first seven months of 2025, bolstering local economies through hospitality and guiding services.[4][83][84] Trade complements tourism as a vital economic pillar, centered on cross-border exchanges via the Mekong River. The Vangtao International Checkpoint, linking Champasak to Thailand's Ubon Ratchathani province, serves as a primary conduit for commerce, handling significant volumes of agricultural products and timber exports. In the first half of 2025, this border post generated 939.69 billion Lao kip (approximately $45 million) in customs revenue, exceeding half its annual target and reflecting heightened activity. Special economic zones in Pakse, such as the Pakse-Japan SME SEZ spanning 195 hectares, further enhance trade by providing incentives for investment in processing and logistics.[85][86] Despite these advances, the sector faces challenges including seasonal fluctuations in visitor numbers, with peaks during the dry season from November to April, and the need for enhanced infrastructure to support sustainable expansion. Efforts to address these include targeted promotions under Laos' Visit Laos Year initiatives, which have boosted awareness of Champasak's heritage sites while integrating brief references to its agricultural exports as complementary draws for agrotourism.[87][88]Infrastructure

Transportation Networks

Champasak province's transportation infrastructure is dominated by its road network, with National Road 13 (NR13) functioning as the primary north-south corridor, extending roughly 200 km through the province and linking the capital Pakse to Savannakhet in the north and the Cambodian border at Veun Kham in the south. This route forms a critical segment of Laos's backbone highway system, facilitating the movement of goods, passengers, and regional trade. The province's total road network includes approximately 1,500 km of paved roads, supporting connectivity to local districts, agricultural areas, and border crossings such as Vang Tao-Chong Mek, which provides direct overland access to Ubon Ratchathani province in Thailand. Key infrastructure like the Lao Nippon Bridge, a 1,380-meter Japanese-funded suspension bridge over the Mekong River in Pakse completed in 2006, enhances east-west mobility within the province by connecting the urban center to eastern districts and tourism sites.[89][90][91] Air travel is centered on Pakse International Airport (PKZ), the province's sole international gateway, which handles daily scheduled flights to Vientiane and Bangkok, along with seasonal or charter services to destinations like Ho Chi Minh City, Siem Reap, and Seoul. Pre-2020 passenger volumes averaged around 300,000 annually, with traffic recovering post-pandemic and projected to reach 400,000 in 2025 amid tourism rebound and airport expansion projects, which commenced in 2025 for improved capacity and facilities.[92][93] The airport's role underscores Champasak's growing integration into regional air routes, supporting both domestic connectivity and inbound tourism. Water transport along the Mekong River remains vital for local and cross-border movement, particularly for passenger ferries and cargo boats serving the 4,000 Islands (Si Phan Don) archipelago in the province's southern reaches. These services connect Pakse and Champasak town to islands like Don Khong, Don Det, and Don Khone, while extending southward toward Cambodian ports via routes like Stung Treng, carrying agricultural goods, tourists, and supplies. However, navigation is constrained by seasonal water levels and formidable rapids at the Khone Falls, limiting larger vessels and requiring portages or smaller craft for through traffic to Cambodia.[94][95] Rail connectivity is absent in Champasak as of 2025, but plans exist to extend the Laos-China Railway southward from Vientiane to reach Pakse, though timelines remain uncertain. This extension, part of broader regional integration efforts, would traverse central provinces before terminating in the south, boosting economic ties without current implementation.[96]Utilities and Recent Developments

Champasak Province benefits from significant hydropower contributions to its electricity supply, primarily through projects like the Don Sahong Hydropower Station, a 325 MW facility (original 260 MW scheme completed in 2019, with an additional 65 MW unit added in 2024) located in Khong District that integrates with the national grid to support both domestic use and regional exports.[97][98] The Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy Hydropower Project, spanning Champasak and Attapeu provinces with a capacity of 410 MW, further bolsters local power generation following its completion despite earlier setbacks, contributing to broader grid connectivity in southern Laos.[99] Planned solar initiatives, such as the Champasak Solar PV Park covering 93.1 hectares and expected to generate 123,000 MWh annually, aim to diversify energy sources and address rural needs on the Bolaven Plateau, where the province's high solar potential supports emerging renewable projects; additional projects include a 150 MW DC photovoltaic station under coordination as of June 2025 and a 760 MW phased solar development announced in February 2025.[100][101][102] Access to water and sanitation in Champasak varies markedly between urban and rural areas, with urban centers like Pakse achieving approximately 95% coverage for improved water supply through piped systems and stormwater infrastructure, while rural access hovers around 70% for basic services.[103] Mekong River-based irrigation projects, including flood protection embankments and 6.8 km of drainage channels in Champasak, enhance water management for agriculture and urban resilience, supported by initiatives like the Mekong Integrated Water Resources Management Project.[104] Ongoing sanitation upgrades in Pakse, such as expanded wastewater treatment, target improved urban services amid national efforts to reach 90% provincial access by 2030.[105] From 2023 to 2025, infrastructure upgrades in Champasak have focused on urban expansion in Pakse through the Asian Development Bank's Pakse Urban Environmental Improvement Project, which enhances water supply, drainage, and environmental services to support regional economic growth.[106] A master plan for tourism development and management on Nagasang, Don Det, and Don Khone islands and surrounding areas, endorsed in November 2024 for implementation from 2025 to 2035, promotes sustainable growth including eco-lodges in protected areas, building on earlier provincial strategies.[107] http://tiigp-laos.org/downloads/other/Champasak%20Province%20Destination%20Management%20Plan%202016-2018.pdf These efforts synergize with transportation enhancements to boost trade.[108] Despite progress, challenges persist, including rural electrification gaps where mini-grids and diesel reliance affect remote Bolaven Plateau communities, limiting full national grid integration.[109] The 2024 floods, which impacted multiple southern provinces including Champasak and damaged homes, crops, roads, and other infrastructure, underscore the need for climate resilience measures, such as improved early warning systems and nature-based flood controls to mitigate future vulnerabilities.[110][111]Culture

Traditions and Festivals

Champasak province, in southern Laos, is home to a rich tapestry of traditions that reflect the daily lives and communal bonds of its residents, often blending animist beliefs with Theravada Buddhist practices. The Baci ceremony, known as soukhouan in Lao, is a central ritual performed to bind the 32 guardian spirits, or kwan, to the body for protection and harmony. This animist-derived custom, adapted within Buddhist contexts, involves tying white cotton strings around the wrists while elders chant blessings and offer food on a flower-adorned altar; it marks life events such as weddings, births, and welcomes for travelers.[112][113] Traditional weaving, particularly the ikat technique (matmi), is a vital craft among ethnic women in Champasak, producing intricate silk textiles featuring Naga motifs symbolizing protection and prosperity. In villages like Don Kho, women use backstrap looms to create these patterns by resist-dyeing yarns before weaving, a practice passed down through generations and recognized as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage for its role in preserving Lao communal identity. These textiles, often in vibrant colors with geometric and mythical designs, are used for clothing like the sinh skirt and ceremonial wraps.[114][115] Cuisine in Champasak centers on sticky rice (khao niao), the staple food steamed in bamboo baskets and eaten by hand, symbolizing communal sharing and sustenance. Accompanied by local herbs such as lemongrass, galangal, and wild greens foraged from the Mekong River basin, it forms the base for dishes like laap (minced meat salad) and tam mak hung (papaya salad), emphasizing fresh, seasonal ingredients in daily meals and rituals. This tradition underscores the province's agrarian lifestyle, where rice cultivation fosters village cooperation.[116][117] Social customs in Champasak's villages revolve around hierarchical structures led by the village headman (nai ban) and elders, who mediate disputes and organize communal labor for rice planting or temple maintenance. Animist beliefs in spirits inhabiting nature and homes coexist seamlessly with Buddhism, as seen in offerings to village guardians (phi ban) before major decisions, blending reverence for ancestors with monastic alms-giving.[118][119] The Wat Phou Festival, held annually in February during the full moon of the third lunar month, is Champasak's premier event, drawing thousands to honor the ancient Khmer-Buddhist heritage at the UNESCO-listed Wat Phou site. Spanning three days, it features boat races on the Mekong, elephant processions, traditional sports like cockfighting and muay lao boxing, and performances of folk music with the bamboo mouth organ (khene), recognized as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Cultural parades, fireworks, and historical reenactments culminate in a candlelit procession, fostering community unity through shared rituals.[120][121] Arts in Champasak thrive through mor lam, a narrative folk singing style accompanied by the khene and percussion, recounting tales of love, morality, and rural life during evening gatherings or festivals. This improvisational tradition, rooted in Lao oral history, engages audiences interactively and is performed by skilled singers in village settings. Shadow puppetry, revived in Champasak through local troupes, draws on Khmer influences with leather figures depicting epics like the Ramayana, projected against a screen amid gamelan-like music and comedy skits to educate and entertain. These performances, often held outdoors, preserve storytelling as a communal bond.[122][123]Religious Practices and Heritage

Theravada Buddhism is the predominant religion in Champasak province, practiced by the majority of the lowland Lao population, which forms the ethnic core of the region and approaches universality among ethnic Lao communities, reflecting national trends where it constitutes around 65% of the overall population. The province hosts numerous Buddhist temples, or wats, scattered across districts, serving as centers for worship and community life; notable examples include Wat Luang in the provincial capital of Pakse, a key site for religious gatherings. Monk ordinations are a common rite of passage for young men and an esteemed practice for older individuals seeking to accumulate merit, often occurring temporarily during the rainy season retreat known as Vassa.[124][125][126] Among ethnic minorities, particularly Mon-Khmer groups such as the Alak and Laven inhabiting the Bolaven Plateau, animist beliefs persist alongside Buddhism, emphasizing reverence for spirits inhabiting nature and ancestors. These communities maintain spirit houses (baw baan) outside homes and villages to honor protective phi spirits, and shamanic rituals led by moi yau healers invoke khwan—vital life forces—to address illnesses or misfortunes through offerings and chants. A small Cham Muslim community, numbering fewer than 10 individuals in Pakse and comprising less than 1% of the provincial population, practices Sunni Islam quietly, with roots tracing to historical migrations from the ancient Champa kingdom.[119][125][127] Champasak's religious heritage blends Theravada Buddhism with syncretic elements from the Khmer Empire's Hindu-Buddhist traditions, evident in ancient sites that transitioned from Shiva worship to Buddhist veneration over centuries. Naga mythology, portraying serpent guardians of the Mekong River, permeates local folklore as protective deities ensuring fertility and warding off floods, often invoked in rituals along the riverbanks. Daily practices like alms-giving (tak bat), where laypeople offer rice and food to monks at dawn, and merit-making activities such as temple donations foster communal harmony and spiritual accumulation. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, a revival in temple restorations has occurred, with international efforts supporting the conservation of sites like Vat Phou since 2020, enhancing preservation of this shared legacy.[4][128][129][130]Landmarks

Historical Sites

Champasak province is renowned for its Khmer-era archaeological sites, which form a key part of the region's man-made heritage. The most prominent is Wat Phou Champasak, a UNESCO World Heritage Site inscribed in 2001, recognized for its exceptionally well-preserved cultural landscape spanning over 1,000 years.[4] This ancient Khmer temple complex, constructed primarily between the 5th and 12th centuries, features a series of galleries, shrines, and water management structures aligned along a central axis from the Phou Kao mountain to the Mekong River plain.[4] Key elements include a sacred spring at the site's base and multiple barays (reservoirs) integrated with the natural terrain, reflecting sophisticated hydraulic engineering typical of Khmer architecture.[4] Located approximately 6 km from the Mekong River, the complex served as a major Hindu worship center dedicated to Shiva before transitioning to Buddhist use.[131] Complementing these ruins, the Champasak Historical Heritage Museum in Pakse houses a collection of artifacts spanning from the Chenla period (6th–8th centuries) through the Khmer era to the French colonial period.[132] Exhibits include Dong Son bronze drums, stone carvings unearthed from the Bolaven Plateau, and inscribed stelae in Tham script dating from the 15th to 18th centuries, providing insights into the province's pre-Khmer and post-Khmer material culture.[132] Another notable site is the Oum Muong ruins (also known as Wat Tomo or Uo Moung), a lesser-known late 9th-century Khmer temple located near the Bolaven Plateau and a tributary of the Mekong.[133] This Hindu temple features a two-tiered brick structure partially reclaimed by jungle, constructed during the reign of Khmer kings and exemplifying early Angkorian influences with its elevated platform and remaining lintels.[133] Preservation efforts for these sites are overseen by Laos's Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism, which coordinates international cooperation to maintain their integrity.[134] Following restorations completed in recent years, including those discussed at the Seventh International Coordination Meeting for Vat Phou Champasak in November 2023, visitor guidelines emphasize restricted access to sensitive areas, no climbing on structures, and adherence to waste management protocols to prevent erosion and vandalism.[135] These measures align with UNESCO's ongoing state of conservation reports, ensuring the sites' long-term protection amid increasing tourism.[134]Natural Attractions

Champasak Province boasts a diverse array of natural attractions, including dramatic waterfalls, riverine archipelagos, and highland plateaus that draw visitors for their scenic beauty and recreational opportunities. These sites, primarily along the Mekong River and the Bolaven Plateau, offer trekking, kayaking, and wildlife viewing amid lush tropical landscapes. The province's natural features are enhanced by its position in southern Laos, where the Mekong's flow creates unique ecosystems supporting rare species.[2] Khone Phapheng Falls, located 150 kilometers south of Pakse near the Cambodian border, is the largest waterfall in Southeast Asia by volume, consisting of a series of cascading rapids stretching over 10 kilometers along the Mekong River. The falls feature a maximum drop of 21 meters, producing a thunderous roar and mist that envelops the surrounding area, making it a prime spot for viewing the power of the river's seasonal floods. Nearby, in the calmer pools below the rapids, endangered Irrawaddy dolphins can occasionally be spotted during boat tours, adding to the site's appeal for nature enthusiasts.[136][2] The 4,000 Islands, or Si Phan Don, form a sprawling archipelago in the Mekong River near the border, comprising numerous islets where only a few, such as the largest Don Khong and the popular Don Det, are inhabited. This biodiversity hotspot supports kayaking excursions through narrow channels lined with mangroves and offers glimpses of the rare Irrawaddy dolphins, one of the few remaining freshwater populations in the world. As of early 2025, the Mekong River population is estimated at approximately 107 individuals and is classified as critically endangered.[137] Visitors can explore the islands by bicycle or boat, immersing in the tranquil waterways that teem with birdlife and aquatic flora during the dry season.[2] On the Bolaven Plateau, at elevations of 1,000 to 1,350 meters above sea level in the northeastern part of the province, Tad Fane and Tad Yuang waterfalls provide striking contrasts in scale and accessibility. Tad Fane, situated 38 kilometers from Pakse within the Dong Hua Sao National Protected Area, features twin cascades from the Champi and Pak Koot rivers plummeting 120 meters into a deep gorge, ideal for trekking along elevated viewpoints. Nearby Tad Yuang, about 40 meters high, descends in multiple tiers through lush jungle, with trails leading to swimming pools and picnic areas surrounded by seasonal wildflowers. The plateau's volcanic soils also sustain expansive Arabica coffee plantations and ethnic minority villages, offering panoramic vistas of rolling hills and cultivated terraces that highlight the region's agricultural heritage.[136][2]References

- https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Pakse