Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chinese animation

View on Wikipedia

Chinese animation or Chinese anime refers to animation made in China. In Chinese, donghua (simplified Chinese: 动画; traditional Chinese: 動畫; pinyin: dònghuà) describes all animated works, regardless of style or origin. However, outside of China and in English, donghua is colloquial for Chinese animation and refers specifically to animation produced in China.

History

[edit]The history of animated moving pictures in China began in 1918 when an animation piece from the United States titled Out of the Inkwell landed in Shanghai. Cartoon clips were first used in advertisements for domestic products. Though the animation industry did not begin until the arrival of the Wan brothers in 1926. The Wan brothers produced the first Chinese animated film with sound, The Camel's Dance, in 1935. The first animated film of notable length was Princess Iron Fan in 1941. Princess Iron Fan was the first animated feature film in Asia and it had great impact on wartime Japanese Momotarō animated feature films and later on Osamu Tezuka.[1] China was relatively on pace with the rest of the world up to the mid-1960s,[2] with the Wan's brothers Havoc in Heaven earning numerous international awards.

China's golden age of animation would come to an end following the onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966.[3] Many animators were forced to quit. If not for harsh economic conditions, the mistreatment of the Red Guards would threaten their work. The surviving animations would lean closer to propaganda. By the 1980s, Japan would emerge as the animation powerhouse of Eastern Asia, leaving China's industry far behind in reputation and productivity. Though two major changes would occur in the 1990s, igniting some of the biggest changes since the exploration periods. The first is a political change. The implementation of a socialist market economy would push out traditional planned economy systems.[4] No longer would a single entity limit the industry's output and income. The second is a technological change with the arrival of the Internet. New opportunities would emerge from Flash animations and the contents became more open. Today China is drastically reinventing itself in the animation industry with greater influences from Hong Kong and Taiwan.

As China’s economic reform reached its height, the 1990s and early 2000s gave way to a relatively open television and film market, where Japanese and American animation powerhouses found a receptive audience among Chinese moviegoers. As government-backed funding dried up and investors flocked to more profitable businesses, animation outsourcing started to take off in China, where cartoon factories sprung up, churning out frames for TV series and movies owned by foreign clients from Japan and the U.S.[5]

The 2004 cartoon series Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, a slapstick-coyote-and roadrunner-like cartoon, became a huge success in China. Pleasant Goat and his goat pals became cultural icons for China, and a powerful soft power tool in foreign relations and brought light and helped the trend of globalization. The show was not only popular with children but surprisingly adults as well. Although there was some controversy for being too violent the show was banned during a censorship on violence and pornography in China.[6]

Terminology

[edit]

Chinese animations today can best be described in two categories. The first type are "conventional animations", produced by corporations of well-financed entities. These content falls along the lines of traditional 2D cartoons or modern 3D CG animated films distributed via cinemas, DVD, or broadcast on TV. This format can be summarized as a reviving industry coming together with advanced computer technology and low cost labor.[7]

The second type are "webtoons", produced by corporations or sometimes just individuals. These contents are generally flash animations ranging anywhere from amateurish to high quality, hosted publicly on various websites. While the global community has always gauged industry success by box office sales. This format cannot be denied when measured in hits among a population of 1.3 billion in just mainland China alone. Most importantly it provides greater freedom of expression on top of potential advertising.

Characteristics

[edit]In the 1920s, the pioneering Wan brothers believed that animations should emphasize on a development style that was uniquely Chinese. This rigid philosophy stayed with the industry for decades. Animations were essentially an extension of other facets of Chinese arts and culture, drawing more contents from ancient folklores and manhua. There is a close relationship between Chinese literature works and classic Chinese animation. A significant number of classical Chinese animation films were inspired and prototyped by ancient Chinese literature.[8] An example of a traditional Chinese animation character would be Monkey King, a character transitioned from the classic literature Journey to the West to the 1964 animation Havoc in Heaven. Also drawing on tradition was the ink-wash animation developed by animators Te Wei and Qian Jiajun in the 1960s. Based on Chinese ink-wash painting, several films were produced in this style, starting with Where is Mama (1960).[9] However, the technique was time-consuming and was gradually abandoned by animation studios.[10]

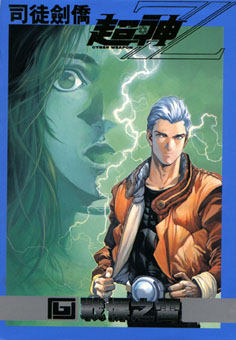

The concept of Chinese animations have begun loosening up in recent years without locking into any particular one style. One of the first revolutionary change was in the 1995 manhua animation adaptation Cyber Weapon Z. The style consist of characters that are practically indistinguishable from any typical anime, yet it is categorized as Chinese animation. It can be said that productions are not necessarily limited to any one technique; that water ink, puppetry, computer CG are all demonstrated in the art.

Newer waves of animations since the 1990s, especially flash animations, are trying to break away from the tradition. GoGo Top magazine, the first weekly Chinese animation magazine, conducted a survey and proved that only 1 out of 20 favorite characters among children was actually created domestically in China.[11]

Conventional animation market

[edit]

The demographics of the Chinese consumer market show an audience where 11% are under the age of 13, 59% between 14 and 17, and 30% over 18 years of age. Potentially 500 million people could be identified as cartoon consumers.[12] China has 370 million children, one of the world's largest animation audiences.[13]

From 2006 to present, the Chinese government has considered animation as a key sector for the birth of a new national identity and for the cultural development in China. The government has started to promote the development of cinema and TV series with the aim of reaching 1% of GDP in the next five years against an investment of around RMB250-350 million (€29-41 million). It supported the birth of about 6000 animation studios and 1300 universities which provide animation studies. In 2010, 220,000 minutes of animations were produced, making China the world's biggest producer of cartoons on TV.[14]

In 1999, Shanghai Animation Film Studio spent 21 million RMB (about US$2.6 million) producing the animation Lotus Lantern. The film earned a box office income of more than RMB 20 million (about US$2.5 million), but failed to capitalize on any related products. The same company shot a cartoon series Music Up in 2001, and although 66% of its profits came from selling related merchandise, it lagged far behind foreign animations.[11]

The year 2007 saw the debut of the popular Chinese Series, The Legend of Qin. It boasted impressive 3d graphics and an immersive storyline. Its third season was released on 23 June 2010. Its fourth season is under production.

One of the most popular manhua in Hong Kong was Old Master Q. The characters were converted into cartoon forms as early as 1981, followed by numerous animation adaptations including a widescreen DVD release in 2003. While the publications remained legendary for decades, the animations have always been considered more of a fan tribute. And this is another sign that newer generations are further disconnected with older styled characters. Newer animations like My Life as McDull has also been introduced to expand on the modern trend.

In 2005, the first 3D CG-animated movie from Shenzhen China, Thru the Moebius Strip was debuted. Running for 80 minutes, it is the first 3D movie fully rendered in mainland China to premiere in the Cannes Film Festival.[15] It was a critical first step for the industry. The immensely popular kids's animated series Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf came out the same year.

In November 2006, an animation summit forum was held to announce China's top 10 most popular domestic cartoons as Century Sonny, Tortoise Hanba's Stories, Black Cat Detective, SkyEye, Lao Mountain Taoist, Nezha Conquers the Dragon King, Wanderings of Sanmao, Zhang Ga the Soldier Boy, The Blue Mouse and the Big-Faced Cat and 3000 Whys of Blue Cat.[16] Century Sonny is a 3D CG-animated TV series with 104 episodes fully rendered.

In 2011, Vasoon Animation released Kuiba. The film tells the story of how a boy attempts to save a fantasy world from an evil monster who, unknowingly, is inside of him. The film borrows from a Japanese "hot-blooded" style, refreshing the audience's views on Chinese animation. Kuiba was critically acclaimed, however it commercially fell below expectations.[17] It was reported that the CEO Wu Hanqing received minority help from a venture capital fund at Tsinghua University to complete "Kuiba."[18] This film also holds the distinction of being the first big Chinese animation series to enter the Japanese market.[19] From July 2012 to July 2013, YouYaoQi released One hundred thousand bad jokes.

In 2015, Monkey King: Hero Is Back gained $2.85 million in the box office, making it the highest-grossing animated film in China.[20]

The most important award for Chinese animation is the Golden Monkey Award.[21]

Flash animation market

[edit]On 15 September 1999, FlashEmpire became the first flash community in China to come online. While it began with amateurish contents, it was one of the first time any form of user-generated contents was offered in the mainland. By the beginning of 2000, it averaged 10,000 hits daily with more than 5,000 individual work published. Today it has more than 1 million members.[22]

In 2001, Xiao Xiao, a series of flash animations about kung fu stick figures became an Internet phenomenon totaling more than 50 million hits, most of which in mainland China. It also became popular overseas with numerous international artists borrowing the Xiao Xiao character for their own flash work in sites like Newgrounds.

On 24 April 2006, Flashlands.com was launched, hosting a variety of high quality flash animations from mainland China. The site is designed to be one of the first cross-cultural site allowing English speakers easy access to domestic productions. Though the success of the site has yet to be determined.

In October 2006, 3G.NET.CN paid 3 million RMB (about US$380,000) to produce A Chinese odyssey, the flash version of Stephen Chow's A Chinese Odyssey in flash format.[23]

Government's role in the industry

[edit]For every quarter, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television announces the Outstanding Domestic Animated Television Productions, which is given to the works that "persist with correct value guidance" (坚持正确价值导向) and "possess relatively high artistic quality and production standards" (具有较高艺术水准和制作水平), and recommends the television broadcasters in Mainland China to give priority when broadcasting such series.[24]

Criticism

[edit]Statistics from China's State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) indicate domestic cartoons aired 90 minutes each day from 1993 to 2002; by the end of 2004, it increased the airing time of domestic cartoons to two hours per day.[25] The division requested a total of 2,000 provinces to devote a show time of 60,000 minutes to domestically-produced animations and comic works. However, statistics show that domestic animators can only provide enough work for 20,000 minutes, leaving a gap of 40,000 minutes that can only be filled by foreign programs. Though insiders are allegedly criticizing domestic cartoons for its emphasis on education over entertainment.[13]

SARFT also have a history of taking protectionism actions such as banning foreign programming, such as the film Babe: Pig in the City. Doing so would jeopardize the broadcast order of homemade animation and mislead their development according to foreign sources.[26][27]

The Chinese government has consistently implemented censorship measures on media deemed morally objectionable, particularly those featuring graphic and violent content. Numerous media productions have undergone alterations to align with these censorship requirements. In 2021, China made a formal announcement regarding the prohibition of violent, vulgar, and bloody content in children's TV shows. The National Radio and Television Administration issued a statement emphasizing the importance of broadcasting content that is wholesome, and progressive, and promotes values of truth, goodness, and beauty within the realm of cartoons. This over censorship of media is a concern for criticism.[28]

Literature and scholarship

[edit]There is little discussion of Chinese animation in English. Daisy Yan Du's PhD dissertation, On the Move: The Trans/national Animated Film in 1940s–1970s China (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2012), is by far the most systematic analysis of early Chinese animation before 1980.[29] Weihua Wu's PhD dissertation, Animation in Postsocialist China: Visual Narrative, Modernity, and Digital Culture (City University of Hong Kong, 2006), discusses contemporary Chinese animation in the digital age after 1980.[30] Besides the two major works, there are other articles and book chapters written by John Lent, Paola Voci, Mary Farquhar, and others about Chinese animation. The first English-language monograph devoted to Chinese animation was Rolf Giesen's Chinese Animation: A History and Filmography, 1922–2012 (McFarland & Company, Jefferson NC, 2015).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Du, Daisy Yan (May 2012). "A Wartime Romance: Princess iron Fan and the Chinese Connection in Early Japanese Animation". On the Move: The Trans/national Animated Film in 1940s–1970s China (Ph.D.). The University of Wisconsin-Madison. pp. 15–60.

- ^ Du, Daisy Yan (2019). Animated encounters: transnational movements of Chinese animation, 1940s-1970s. Asia pop !. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-7210-6.

- ^ Qing Yun. "Qing Yun" (Archived 21 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine). Qing Yun.com. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ^ Socialist Marketing Economy. "Socialist Marketing Economy." "Socialist Marketing Economy." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ "History of Chinese animation". MCLC Resource Center. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ Jones, Stephanie (2019). ""The Chinese Animation Industry: from the Mao Era to the Digital Age"". USF Scholarship: A Digital Repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center.

- ^ French, Howard W. (1 December 2004). "China Hurries to Animate Its Film Industry". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Chen, Yuanyuan (4 May 2017). "Old or new art? Rethinking classical Chinese animation". Journal of Chinese Cinemas. 11 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1080/17508061.2017.1322786. ISSN 1750-8061. S2CID 54882711.

- ^ Wang, Nan (4 June 2008). "Water-and-Ink animation". China Daily. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ Fang, Liu (20 March 2012). "Is there a future for water-ink animation?". CNTV. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ a b China Today. "China Today." "Chinese Animation Market: Monkey King vs Mickey Mouse." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ Homepage of author Jonathan Clement. "Homepage of author Jonathan Clement Archived 6 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. "Chinese Animation." Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ a b People's Daily Online. ""China Opens Cartoon Industry to Private Investors". People's Daily Online. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ De Masi, Vincenzo (2013). "Discovering Miss Puff: a new method of communication in China" (PDF). KOME: An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry. 1 (2). Hungarian Communication Studies Association: 44, 46. ISSN 2063-7330. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Broadcast Buyers Guide. "Broadcast Buyers Guide." "GDC Technology and Arts Alliance Media Partner for a Digital Screening Premiere at Cannes." Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ China's CityLife. "China's City Life." "Top 10 Domestic Cartoons." Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ "Chinese Animation at a Crossroads". CNTV English. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Kemp, Stuart (24 June 2011). "Beijing Calls the Toons". The Independent. London. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ "China Animation To Be Screened in Japan Before Its Mainland Theater Release". China Screen News. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Jiang, Fei; Huang, Kuo (2017). "Hero is Back- The rising of Chinese audiences: The demonstration of SHI in popularizing a Chinese animation". Global Media and China. 2 (2): 122–137. doi:10.1177/2059436417730893. ISSN 2059-4364. S2CID 194577213.

- ^ China Daily (13 January 2017). "Animated 3-D film 'Bicycle Boy' to hit screens on 13 Jan". english.entgroup.cn. EntGroup Inc. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ FlashEmpire. "FlashEmpire Archived 22 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine. " "FlashEmpire info." Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ^ Embedded Flash Advertising. "Virtual China Org." "Embedded Flash Advertising." Retrieved 21 December 2006. Archived 18 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 国家新闻出版广电总局关于推荐2016年第三季度优秀国产电视动画片的通知 (in Chinese). State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ People's Daily Online. "People's Daily Online." "Cartoon Festival Launches Monkey King Award." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ USA Today. "Usatoday." "Animation Ban." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ BackStageCasting. "BackStageCasting Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine." "China bans TV toons that include live actors." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ^ Schlitz, Heather. "China bans violent or vulgar cartoons and anime as its crackdown on the entertainment industry continues". Business Insider. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Du, Daisy Yan (May 2012). On the Move: The Trans/national Animated Film in the 1940s–1970s China (Ph.D.). The University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- ^ Wu, Weihua (2006). Animation in Postsocialist China: Visual Narrative, Modernity, and Digital Culture. City University of Hong Kong.

External links

[edit]- China's Cartoon Industry Forum

- Remembering Te Wei at AnimationInsider.net

Chinese animation

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins and Early Innovations (1920s–1940s)

Chinese animation emerged in the 1920s amid growing exposure to Western motion pictures, with pioneers adapting imported techniques to local contexts. The Wan brothers—Wan Laiming, Wan Guchan, Wan Chaochen, and Wan Dihuan—played a central role, producing the first known Chinese animated short film, Uproar in the Studio (1926), under the Great Wall Film Company. This hand-drawn work, inspired by foreign cartoons, depicted chaotic animation production, marking an initial foray into the medium using rudimentary cel animation methods.[6] Throughout the 1930s, the Wan brothers continued innovating, establishing their own studio and releasing shorts that incorporated sound by 1935 with The Camel's Dance, China's first animated film with synchronized audio. These early productions drew from traditional Chinese ink painting styles, experimenting with fluid lines and minimalist backgrounds to distinguish from rigid Western approaches, while addressing themes like labor and folklore. The period saw limited output due to technological constraints and political instability, including the Japanese invasion, yet animators persisted in Shanghai, producing over a dozen shorts that blended propaganda elements with entertainment.[7][8] The 1940s culminated in a major breakthrough with Princess Iron Fan (1941), directed by the Wan brothers as Asia's first feature-length animated film, running 86 minutes and adapting an episode from the classical novel Journey to the West. Assembled by a team of over 100 artists over three years, it featured innovative multiplane camera effects and rotoscoping influenced by Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), viewed by the creators in 1939. Produced under wartime conditions in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, the film achieved commercial success, exporting to Japan and inspiring figures like Tezuka Osamu, though its creation relied on cross-cultural exchanges amid geopolitical tensions.[6][9]Golden Age under State Support (1950s–1980s)

Following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, animation production was nationalized and centralized under state auspices, with the animation unit of the Northeast Film Studio relocating to Shanghai in 1950 to form the basis of a dedicated facility.[10] In April 1957, the Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS) was officially established as the country's primary animation center, benefiting from direct government funding and resources that prioritized cultural production aligned with socialist ideology.[11] This state support enabled the studio to employ hundreds of artists and technicians, fostering technical advancements and stylistic innovation despite initial reliance on Soviet-influenced cel animation techniques.[12] Under artistic director Te Wei and contributions from pioneers like the Wan Brothers, SAFS developed a "national style" (minzu fengge) in the 1950s and 1960s, integrating traditional Chinese artistic methods such as ink-wash, gouache on silk, puppetry, and paper-cut into animation to distinguish it from Western models.[13] Pioneering works included the ink-wash short Little Tadpoles Looking for Mama (1960), which used layered rice paper and water-based pigments to simulate the fluidity of traditional Chinese painting, achieving over 1,000 drawings for its simple yet expressive narrative.[14] The two-part feature Havoc in Heaven (1961–1964), adapting the Journey to the West legend of Sun Wukong, exemplified this style with 150,000 hand-drawn cels blending dynamic action sequences and cultural motifs, earning awards at international festivals like the Mannheim Film Festival in 1965.[11] The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) severely disrupted operations, with SAFS closing in 1965 under Mao Zedong's directives; artists were sent for manual labor or political re-education, though limited propaganda pieces, such as animated model operas, continued sporadically to promote revolutionary themes.[15] After Mao's death in 1976, the studio revived under Deng Xiaoping's reforms, producing ambitious features like Prince Nezha's Troubles (1979), China's first large-scale color widescreen animated film involving 400,000 drawings and drawing from Investiture of the Gods mythology to convey themes of filial piety and resistance to tyranny.[16] By the 1980s, SAFS had output over 1,000 shorts and features, including puppet animations like Tales of the Effendi (1980), solidifying Chinese animation's global reputation for artistic merit while serving state goals of cultural education and national pride.[17]Decline Amid Market Reforms (1990s–Early 2000s)

Following China's economic reforms initiated in the late 1970s under Deng Xiaoping, which transitioned the country from a planned economy to a socialist market system, state support for cultural industries like animation diminished significantly by the 1990s.[2] Previously reliant on government subsidies, the Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS)—the dominant national producer—faced mandates to operate on commercial principles, requiring self-financing through box office and broadcast revenues without guaranteed funding.[12] This shift exacerbated financial strains, as animation production cycles remained labor-intensive and slow, averaging years per feature film under traditional cel and ink-wash techniques, ill-suited to rapid market demands.[11] Internal challenges compounded the issue, including a severe brain drain of talent. In the late 1980s and 1990s, animators defected to higher-paying opportunities in advertising, television commercials, and outsourcing for foreign studios, particularly in southern joint ventures offering salaries far exceeding SAFS's state-fixed wages.[12] Production quality suffered from chronic underfunding and a post-1985 policy emphasis on volume over innovation, resulting in diminished artistic output; SAFS profits had already plummeted from 1.43 million yuan in 1987 to 480,000 yuan in 1988, a trend that persisted into the decade with fewer high-caliber works.[18] From 1990 to 1996, national animated film production numbers declined sharply, reflecting broader stagnation as studios prioritized short, low-budget pieces over ambitious features.[19] Externally, the open media market enabled a flood of imported animations, predominantly Japanese anime, which aired extensively on television—up to six or seven series daily by the mid-1990s—capturing youth audiences with dynamic narratives, sophisticated visuals, and themes contrasting the perceived didactic, child-oriented style of domestic donghua.[2] Widespread piracy further eroded potential revenues, as unlicensed VHS and VCD copies of foreign content proliferated without intellectual property enforcement, sidelining Chinese productions that struggled for airtime and theatrical slots.[20] Isolated attempts at commercial revival, such as the 1999 feature Lotus Lantern by SAFS, marked early market experiments but failed to reverse the overall downturn, with the industry producing minimal competitive output until regulatory curbs on foreign imports in 2005–2006.[21]Digital Revival and Commercial Boom (2010s–Present)

The digital era marked a turning point for Chinese animation, transitioning from analog techniques to computer-generated imagery (CGI) and leveraging internet platforms for distribution, which facilitated broader accessibility and audience engagement. By 2010, annual production had exceeded 220,000 minutes, positioning China as the world's largest animation producer by volume.[22] This surge was driven by advancements in digital tools and the rise of streaming services like Bilibili and iQiyi, enabling direct-to-consumer models that bypassed traditional television constraints.[23] Government policies played a pivotal role in fostering this revival, with initiatives dating back to 2001 providing subsidies, tax incentives, and infrastructure support to cultivate domestic content amid competition from imported animations.[24] These measures, including investments in creative industries, aligned with national strategies to promote cultural soft power, resulting in a proliferation of studios adopting 3D animation for cost efficiency and visual appeal.[25] The industry's total output value grew from approximately RMB 88.2 billion in 2013 to over RMB 300 billion by 2023, reflecting a compound annual growth rate fueled by domestic box office successes and derivative merchandise.[23][26] Milestone films exemplified the commercial viability of high-quality donghua. Monkey King: Hero Is Back (2015), a 3D reinterpretation of the classic tale, grossed over RMB 865 million, revitalizing interest in mythological narratives with modern aesthetics.[27] This was followed by Big Fish & Begonia (2016), which blended folklore with environmental themes and earned RMB 265 million despite modest budgets. The pinnacle came with Ne Zha (2019), directed by Jiaozi, which shattered records by amassing RMB 5.02 billion in domestic earnings, equivalent to about $723 million USD, and becoming the highest-grossing animated film globally at the time.[28] These successes demonstrated audience appetite for culturally resonant stories rendered through sophisticated CGI, often rivaling international standards in production values. Television series and web animations further amplified the boom, particularly in genres like xianxia (immortal heroes) and esports adaptations. The King's Avatar (2017), based on a web novel, popularized competitive gaming narratives and garnered millions of views on platforms like Tencent Video, spawning sequels and merchandise empires.[29] Adaptations such as Mo Dao Zu Shi (2018) and Link Click (2021) attracted international fandoms via subtitles, highlighting thematic depth in cultivation and time-travel motifs. By the early 2020s, the sector's expansion included overseas exports, with films like White Snake (2019) achieving notable box office in Japan, signaling growing soft power projection.[28] Ongoing developments underscore sustained momentum, with projections for output value exceeding RMB 300 billion annually and integration of virtual reality and AI in production workflows.[30] However, challenges persist, including regulatory oversight on content and talent retention amid global competition, yet empirical metrics indicate a robust trajectory toward commercialization and innovation.[24]Terminology and Conceptual Framework

Core Definitions and Etymology

Chinese animation, known as donghua (动画; 動畫), refers to the body of animated films, television series, and other media produced primarily in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, though the term most commonly denotes works from the People's Republic of China.[31] It includes techniques ranging from traditional hand-drawn cel animation to contemporary computer-generated imagery (CGI), often drawing on Chinese folklore, mythology, and historical narratives.[32] Within China, donghua broadly applies to all animated content, regardless of stylistic influences or foreign origins, functioning as a generic descriptor equivalent to "animation" in English.[31] Internationally, however, the term has narrowed to specify animation originating from Chinese studios, distinguishing it from Japanese anime or Western cartoons.[33] The etymology of donghua traces to the compound Chinese characters 動畫: 動 (dòng), signifying "motion," "movement," or "to move," and 畫 (huà), denoting "picture," "drawing," or "painting."[31] This literal meaning of "moving pictures" or "moving paintings" reflects the medium's essence as sequential images creating the illusion of motion. The term was adapted from the Japanese dōga (動画), coined in the 1910s–1920s by pioneers like Kenzō Masaoka for early animated films at Nippon Dōga-sha, Japan's first dedicated animation studio established in 1933.[31] Chinese adoption occurred amid early 20th-century cultural exchanges, with donghua gaining prominence in the 1940s–1950s as domestic production formalized post-World War II.[34] Prior to donghua's standardization, alternative terms shaped early discourse. Katong (卡通), borrowed from English "cartoon" via Japanese katō (from "cartoons"), emerged in the 1920s–1930s for imported and nascent local works, emphasizing humorous or illustrative shorts.[31] Meishupian ("artistic films") was occasionally used for aesthetically driven animations, but donghua dominated during the 1949–1976 socialist era, specifically for cel-based techniques under state-sponsored studios like Shanghai Animation Film Studio.[31] In the 1990s, dongman (動漫), blending donghua and manhua (comics), arose in Taiwan to denote the integrated animation-comics culture, later influencing cross-strait usage but remaining distinct from pure donghua.[34] These shifts reflect technological evolution and cultural borrowing, with donghua persisting as the core term due to its neutrality and alignment with medium-specific innovation over stylistic labels.[32]Distinctions from Related Forms

Chinese animation, or donghua, is distinguished from Japanese anime primarily by its national origin and cultural embedding, as donghua encompasses all animated works produced in China, reflecting indigenous folklore, philosophy, and artistic traditions rather than adopting the stylistic or thematic conventions associated with anime.[35] While anime often draws from Japanese Shintoism, samurai lore, and yokai mythology, donghua prioritizes Chinese elements such as xianxia (immortal hero fantasy), wuxia (martial arts epics), and classics like Journey to the West, incorporating Confucian values of filial piety and societal harmony.[33] Stylistically, donghua frequently employs 3D CGI for dynamic realism, as seen in series like Lord of Mysteries, contrasting anime's predominant 2D hand-drawn fluidity, though some donghua blend both for hybrid effects.[33] In contrast to Western animation, which typically emphasizes episodic structures, character-driven humor, and internal motivations for movement—often targeting family audiences—donghua favors serialized narratives adapted from web novels, with external forces driving action and a focus on epic scales rooted in historical or mythical contexts.[36] Western styles prioritize exaggerated, fluid motions and bright, simplified designs for broad appeal, whereas donghua integrates traditional Chinese aesthetics like ink-wash painting's negative space and focus perspective, evoking a sense of void and antiquity, as in early ink animation techniques.[37] This derives from influences such as shadow puppetry and Peking opera, yielding compositions that use bold lines, gradients, and cultural motifs absent in Western cartoon traditions.[38]Furthermore, donghua differentiates from static forms like manhua (Chinese comics) by its emphasis on temporal motion and visual storytelling, transforming illustrated narratives into animated sequences that exploit technological shifts, such as CGI to render mythical battles or cultivation progressions, rather than relying solely on sequential panels.[34] Productionally, donghua benefits from state incentives and private crowdfunding, enabling large-scale adaptations of domestic IP, unlike Western animation's studio-driven originals or anime's manga-based pipelines, which can limit thematic scope to national idioms.[35] These distinctions underscore donghua's role as a medium for cultural export, blending heritage with modern tech to assert Chinese identity amid global influences.[39]

Stylistic and Thematic Features

Artistic Techniques and Visual Aesthetics

Chinese animation has historically drawn on traditional artistic techniques rooted in classical Chinese painting and folk arts, particularly during the "national style" period pioneered by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio from the 1950s to the 1980s. These methods included hand-drawn cel animation adapted to emulate ink wash painting, where animators layered translucent inks to achieve fluid brushstrokes and subtle gradations mimicking gongbi and xieyi styles, as in the 1960 short Where Is Mama?, which utilized watercolor effects for emotional depth in natural landscapes.[40] Puppet animation and paper-cutting techniques were also innovated, employing articulated clay or paper figures with multiplane cameras to create depth and dynamic movement inspired by shadow puppetry, evident in works like The Proud General (1956), which integrated folk art motifs for textured, layered visuals.[17] The landmark Havoc in Heaven (1961–1964), produced by the same studio, exemplified these techniques through over 160,000 hand-drawn frames featuring exaggerated poses and flowing lines derived from Chinese opera aesthetics, with vibrant palettes and rhythmic compositions that prioritized artistic conception over photorealism.[20] This era's aesthetics emphasized white space, impressionistic rendering, and cultural symbolism, such as mythical motifs rendered in sparse, evocative strokes to convey philosophical undertones akin to Chan influences in traditional art.[41] In contemporary donghua, artistic techniques have shifted toward digital production, incorporating 2D/3D CGI hybrids that simulate traditional ink aesthetics via software like Photoshop for brush simulation and Maya for 3D modeling, reducing manual labor while enabling complex layering and camera dynamics.[42] Films like Big Fish & Begonia (2016) blend hand-drawn elements with CGI particle effects and watercolor shaders, creating ethereal, fluid visuals that fuse ancient ink-painting's artistic conception with modern spectacle, as seen in its dreamlike backgrounds and character fluidity.[40] Similarly, Summer (2003) introduced 3D ink-painting by combining motion capture with digital brushstrokes, allowing non-linear perspectives that enhance immersion without sacrificing Eastern impressionism.[42] Visual aesthetics in modern works often prioritize hybridity, merging national style's emphasis on brushwork and cultural motifs—such as flowing robes and mythical beasts—with 3D realism for commercial appeal, as in White Snake (2019), where elegant CGI rendering elevates wuxia dynamics through detailed textures and lighting that evoke traditional scroll paintings.[40] This evolution reflects pragmatic adaptations to production efficiency, yet retains distinctive traits like rhythmic line work and symbolic sparsity, distinguishing donghua from purely Western or Japanese influences despite superficial anime-style borrowings in some series.[42]Narrative Structures and Cultural Motifs

Chinese animation frequently employs serialized narrative structures derived from web novels and manhua adaptations, particularly in the dominant xianxia genre, where protagonists undergo progressive cultivation of internal energy (qi) to ascend through hierarchical realms, confronting rivals, sects, and supernatural threats in a framework of personal empowerment and moral trials.[43][44] This structure emphasizes linear power escalation, often spanning hundreds of episodes, with recurring tropes such as foundational training stages (e.g., Qi Condensation or Foundation Establishment), breakthrough battles, and dao enlightenment pursuits, reflecting a causal progression from weakness to transcendence.[45] Earlier works, from the 1960s Shanghai Animation Film Studio era, favored episodic formats drawn from classical tales, incorporating liubai (intentional narrative voids) inspired by ink-wash painting traditions to evoke philosophical ambiguity and viewer inference.[41] Cultural motifs in Chinese animation are deeply rooted in mythological and historical sources, prominently featuring adaptations of Journey to the West's Sun Wukong (Monkey King) or Nezha's rebellious deity archetype, which symbolize defiance against cosmic order and filial redemption within Confucian hierarchies.[46][47] Taoist influences manifest in motifs of harmony with the dao, cyclical rebirth through elixirs or reincarnation, and immortal cultivation quests, while Buddhist elements underscore karma's inexorable causality and enlightenment via detachment from worldly desires.[48] Confucian values reinforce themes of loyalty to family and state, hierarchical respect, and collective harmony over individualism, often portrayed through sect alliances or imperial folklore, as seen in folk tale-derived stories promoting moral rectitude and ancestral veneration.[45] These motifs serve to propagate traditional cultural inheritance amid modernization, with visual integrations like dragon guardians or phoenix rebirths embedding empirical folklore realism into fantastical narratives.[47]Comparisons with Global Peers

Chinese animation, known as donghua, exhibits distinct stylistic and production differences from Japanese anime, its closest global peer in serialized, genre-driven output. Anime typically relies on 2D hand-drawn techniques that prioritize exaggerated expressions, dynamic action sequences, and meticulous frame-by-frame detailing, fostering a fluid, emotive aesthetic honed over decades by studios like Studio Ghibli and Kyoto Animation. In contrast, donghua predominantly employs 3D computer-generated imagery (CGI), which enables cost-efficient mass production but often yields stiffer movements and less nuanced facial animations, as evidenced by series like The King's Avatar where CGI prioritizes scale over subtlety. This technical divergence stems from China's heavier investment in digital pipelines since the 2010s, allowing for rapid iteration in fantasy spectacles drawing from wuxia martial arts and ancient mythology, unlike anime's fusion of samurai lore, mecha designs, and psychological introspection.[33][49] Thematically, donghua emphasizes epic cultivation narratives—protagonists ascending through spiritual hierarchies via rigorous training and moral trials—rooted in Daoist and Confucian motifs, which differ from anime's frequent exploration of existential ennui, social alienation, or post-war humanism. Production volumes underscore Japan's edge in creative export: anime generated approximately USD 34.3 billion globally in 2024, with over 60% derived from international licensing and merchandise, compared to donghua's estimated USD 41.8 billion in total domestic revenue for 2023, largely confined to platforms like Bilibili and Tencent Video. Japan's industry, supported by a freelance artist ecosystem and minimal state interference, sustains higher originality and fan-driven innovation, while Chinese studios grapple with formulaic tropes and regulatory mandates that curb narrative risks, limiting crossover appeal despite surging output of over 500 series annually by 2023.[50][51] Relative to Western animation, dominated by U.S. giants like Disney and Pixar, donghua diverges in format and audience targeting. Western productions favor polished 3D feature films with broad, family-oriented storytelling and photorealistic rendering, as in Toy Story (1995) or Frozen (2013), which amassed billions in worldwide box office through theatrical dominance and theme park synergies. Donghua, conversely, thrives in long-form web series optimized for mobile viewing, catering to young adult males with power fantasies and minimal character arcs, yielding modest international box office—e.g., Ne Zha (2019) earned USD 728 million globally but trailed Disney's averages. U.S. animation benefits from venture capital and IP franchising, projecting a segment of the global market exceeding USD 400 billion by 2025, whereas China's growth, fueled by state subsidies and a 1.4 billion-person domestic base, faces hurdles in cultural export due to subtitles' barriers and content homogenization under censorship, resulting in under 5% of donghua revenue from abroad as of 2023.[52][51][53] Economically, China's animation sector has expanded rapidly, capturing about 10-15% of the Asia-Pacific market share by 2025 through vertical integration with gaming and e-commerce, outpacing Japan's stagnant domestic viewership amid an aging population. Yet, global peers maintain advantages in soft power: U.S. exports leverage Hollywood's distribution networks, while Japan's otaku culture drives USD 20+ billion in overseas merchandise alone. Donghua's strengths lie in scalable CGI for high-fantasy worlds and alignment with nationalistic themes, but weaknesses include derivative aesthetics mimicking anime without matching its emotional depth, overworked pipelines akin to Japan's karoshi culture but exacerbated by 996 schedules, and limited innovation due to institutional biases favoring propaganda over artistic risk. These factors position donghua as a rising domestic powerhouse rather than a direct rival to established international paradigms.[54][55]Industry Composition and Production

Key Studios and Talent Pipeline

Haoliners Animation League, established in 2013 in Shanghai, ranks among China's leading 2D animation producers, with credits including the donghua series The Daily Life of the Immortal King (2020) and contributions to anthology films like Flavors of Youth (2018).[56][57] Light Chaser Animation Studios, also founded in 2013 and based in Beijing, focuses on CG feature films, producing titles such as Little Door Gods (2016), White Snake (2019), and New Gods: Nezha Reborn (2021), emphasizing mythological narratives adapted for modern audiences.[58][56] Fantawild Animation Inc., designated a National Key Animation Enterprise, dominates family-oriented content through its Boonie Bears franchise, which has amassed approximately $1.3 billion in cumulative box office earnings across multiple theatrical releases since 2012.[59][60] Platform-integrated studios further bolster production capacity; Bilibili's in-house animation efforts have yielded original donghua like Link Click (2021 onward), alongside announcements of over 30 new titles planned for rollout in subsequent years to capitalize on streaming demand.[61] These studios often collaborate with tech giants such as Tencent and iQiyi, which provide funding and distribution but rely on specialized firms for core creative output.[56] The talent pipeline originates in higher education, with the Beijing Film Academy launching China's first dedicated animation department in 1993, fostering systematic training that has expanded the sector's skilled labor pool exponentially over three decades.[5] Leading institutions like Jilin Animation Institute—established as a specialized animation college—and Communication University of China deliver curricula in 2D/3D techniques, digital effects, and narrative design, graduating thousands annually to meet industry demands exceeding 200,000 professionals across more than 10,000 studios.[62][63] University-enterprise partnerships, including internships and co-developed programs, integrate practical pipelines with academic theory, though challenges persist in retaining top talent amid competitive global outsourcing.[64]Technological Shifts and Methods

Chinese animation production historically depended on analog techniques, including hand-drawn cel animation, cut-out animation, and puppetry, as practiced by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio during its formative years from the 1950s to the 1980s.[65] These methods emphasized artisanal craftsmanship, such as ink-wash simulation through layered painting and multiplane effects to achieve depth, but were labor-intensive and limited in scalability for commercial output.[66] The transition to digital technologies commenced in the late 1980s with initial experiments in computer-generated imagery (CGI) for simulating traditional ink-painting aesthetics, enabling precise control over brush strokes and fluidity that manual methods struggled to replicate consistently.[42] By the early 2000s, broader adoption of digital ink-and-paint systems replaced physical cels, facilitated by software advancements and increasing computer accessibility, which reduced production costs and timelines while preserving stylistic elements like exaggerated expressions rooted in Chinese opera influences.[2] This shift aligned with market reforms, allowing studios to compete with imported anime through efficient workflow digitization.[27] A pivotal advancement occurred with the embrace of 3D CGI, starting with China's first 3D animated feature, Little Tiger Banban, released in 2001, which utilized modeling and rendering techniques to create volumetric environments beyond 2D constraints.[67] Productions like Thru the Moebius Strip (2005) further demonstrated full CGI pipelines, involving 3D modeling, rigging, and particle simulations for sci-fi effects, marking a departure from planar animation toward immersive spatial dynamics.[68] In contrast to 2D's frame-by-frame drawing, 3D methods employ skeletal animation and physics-based simulations, enabling reusable assets and complex crowd or action sequences, though requiring specialized skills in tools for topology and shading.[69] Contemporary donghua production predominantly integrates hybrid 2D-3D workflows, where 2D excels in character emoting and stylization via vector graphics, while 3D handles backgrounds and mechanical elements for efficiency in high-volume series output.[70] Since the 2010s, visual effects (VFX) integration has surged, with breakthroughs in rendering farms and motion capture supporting blockbusters like Nezha (2019), which combined procedural generation for hair and cloth dynamics to achieve photorealistic yet fantastical visuals.[68] This evolution reflects causal drivers of technological import, talent training in CGI pipelines, and economic imperatives for rapid iteration amid streaming demands, though challenges persist in matching global standards for seamless 2D-3D blending.[71] Emerging AI applications, such as automated inbetweening and style transfer, are augmenting these methods as of 2024, potentially streamlining rote tasks but raising concerns over artistic authenticity.[72]Market Segments and Distribution Channels

The Chinese animation market is segmented primarily by audience demographics and production formats, with a strong emphasis on youth and young adult viewers aged 18-30, who form the core consumer base for contemporary donghua series featuring complex narratives in genres like fantasy and wuxia.[73] Children's content, often in traditional 2D styles aimed at audiences under 13, constitutes a smaller but persistent segment focused on educational and moralistic themes, historically supported by state media.[74] Series targeting teenagers (14-17) bridge these groups, blending action-oriented stories with cultural motifs, while adult-oriented productions remain niche but growing through web-exclusive releases.[75] Domestically, distribution relies heavily on digital streaming platforms, which accounted for the majority of consumption by 2024 as traditional television viewership declined amid smartphone penetration exceeding 70% among urban youth.[74] Key channels include Bilibili, iQiyi, and Tencent Video, where user-generated content and short-form episodes drive engagement; for instance, Bilibili's "bullet chatting" feature fosters community interaction, boosting retention for serialized donghua.[76] Theatrical releases serve as a high-impact channel for feature films, exemplified by Ne Zha 2 (2025), which leveraged cinema distribution to achieve record box office performance and elevate animation's share of China's film market.[77] Internationally, distribution has expanded via licensing deals with global platforms, targeting overseas Chinese diaspora and Western audiences interested in non-Japanese animation alternatives. Crunchyroll has streamed titles like Renegade Immortal (2025, 24 episodes) and Throne of Seal (2025, 78 episodes) with multilingual subtitles, facilitating access in regions like North America and Europe.[78] Netflix and similar services have acquired select donghua for broader reach, though penetration remains limited compared to domestic channels due to cultural adaptation challenges and competition from Japanese anime.[76] This outbound strategy supports soft power goals, with 2024 exports contributing to animation's role in China's cultural industries output exceeding 300 billion RMB.[26]Governmental Influence and Policy Framework

State Support Mechanisms and Incentives

The Chinese government has prioritized the animation industry as a component of cultural and creative sectors since the early 2000s, establishing national-level policies to foster growth through direct funding, tax relief, and regulatory preferences. In 2006, the State Council issued the "Notice on Some Opinions on the Development of China’s Animation Industry," which framed animation as a strategic priority and outlined a framework for industry expansion, including financial support and infrastructure development.[79] This was followed in 2008 by the Ministry of Culture's "Some Opinions on Supporting the Development of China’s Animation Industry," which provided targeted assistance for production and talent cultivation.[80] Key incentives include tax benefits and enterprise recognition programs. The 2008 Trial Measures on the Recognition of Animation and Cartoon Enterprises, jointly issued by the Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Finance, and State Administration of Taxation, defined qualifying animation firms eligible for policy advantages such as reduced corporate income tax rates and value-added tax rebates on equipment imports.[80] These measures aimed to lower operational costs and encourage investment. Additionally, broadcast quotas mandate that television stations allocate a minimum percentage of airtime—typically around 50-60% in prime slots—to domestic animation content, incentivizing production by guaranteeing market access.[73] Funding programs operate at both central and local levels, often tied to five-year plans. The 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015) for the animation industry emphasized increased financial inputs from government budgets to support original content creation and intellectual property protection.[81] The subsequent "13th Five-Year Plan" period (2016-2020) extended this through the Cultural Industry Development Plan, incorporating animation into broader subsidies for digital media. Local initiatives provide direct subsidies; for instance, in 2023, Beijing's Xicheng District allocated 50 million yuan annually in special funds for animation-related industries. More recently, Guangdong Province introduced a 2025 policy offering subsidies up to 8.6 million yuan per project to promote original intellectual property in animation and film.[82][83] These mechanisms reflect a state-driven approach to building domestic capacity, with incentives focused on output volume and ideological alignment rather than unrestricted innovation, as evidenced by integration into national cultural propaganda goals.[84] While effective in scaling production—contributing to market growth projections of $35.7 billion by 2025—critics note that heavy reliance on subsidies can distort market signals and prioritize quantity over quality.[25]Regulatory Constraints Including Censorship

The National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), under the Communist Party of China's Central Propaganda Department, oversees regulatory constraints on Chinese animation production, distribution, and content, requiring pre-approval for all broadcast and online releases to ensure alignment with socialist core values.[85] These rules mandate that works avoid themes endangering national security, unity, or honor; inciting subversion of state power; or promoting ethnic hatred, superstition, or pornography, with animation facing heightened scrutiny due to its youth-oriented audience.[86] Producers must obtain permits for filming, importation of foreign elements, and platform uploads, often involving script reviews and revisions to excise politically sensitive or morally "decadent" content, such as excessive individualism or Western cultural influences.[80] Censorship extends to thematic prohibitions, including restrictions on supernatural depictions that could foster superstition—though cultural adaptations like those from Journey to the West receive exemptions if framed patriotically—and bans on graphic violence or rebellion against authority, as seen in the 2013 temporary suspension of the popular children's series Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf for alleged excessive animated violence.[87] Queer-themed donghua, particularly boys' love (BL) narratives, face severe alterations or outright suppression; for instance, adaptations of Mo Xiang Tong Xiu's novels such as The Founder of Diabolism and Heaven Official's Blessing have had romantic subplots diluted or removed during production to comply with 2021 NRTA guidelines cracking down on "effeminate" portrayals and non-normative relationships.[88] Platforms like Bilibili and iQiyi enforce real-time monitoring and self-censorship, deleting episodes or user comments that violate rules, contributing to a chilling effect where studios preemptively align content with "main melody" propaganda promoting Party loyalty and national rejuvenation.[86] While recent NRTA initiatives, such as the August 2025 plan to boost animation output for soft power, signal some regulatory easing on production quotas, core ideological controls persist, limiting narrative diversity and favoring state-endorsed motifs over experimental or critical storytelling.[89] This framework has led to extensive self-censorship by studios, with non-compliance risking fines, shutdowns, or blacklisting, as evidenced by broader media purges under Xi Jinping's administration since 2012, which prioritize causal stability over unfettered creative expression.[86]Economic Dynamics and Performance

Market Scale and Growth Metrics

The total output value of China's animation industry exceeded 300 billion yuan (approximately 41.8 billion USD) in 2023.[82] This figure encompasses production, derivatives, and related economic activities, as reported by the China Animation Association.[5] The sector achieved a year-over-year revenue growth rate of 19 percent in 2023, driven by increased domestic content production and consumption.[26] Historical data indicate steady expansion, with output surpassing 220 billion yuan prior to 2023.[90] Subsegments such as animation, visual effects, and post-production are projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.06 percent from 2025 onward, reaching higher valuations amid technological integration and market maturation.[91] For the narrower donghua (Chinese anime) market, revenues stood at 2.24 billion USD in 2024, with expectations of expansion to 4.6 billion USD by 2030 at an implied CAGR exceeding 12 percent.[92]| Year | Output Value (billion yuan) | Approximate USD Equivalent (billion) | YoY Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2023 | >220 | ~30.6 | N/A |

| 2023 | >300 | ~41.8 | 19% |

Revenue Streams and Box Office Milestones

Chinese animation derives revenue primarily from theatrical box office earnings for feature films, digital streaming and video-on-demand platforms for television series and shorts, and ancillary sources including merchandise sales, intellectual property licensing, advertising tie-ins, and extensions into gaming and derivatives.[30] Content payments from broadcasters and platforms form a core stream, supplemented by advertising revenue during distribution and profits from derivative products like toys, apparel, and mobile games linked to popular titles. The industry's total output value expanded to 221.2 billion yuan by 2023, reflecting growth driven by these diversified channels amid rising domestic consumption.[30] Box office performance has marked key milestones, particularly for feature films adapting mythological tales, with theatrical releases serving as primary revenue drivers for high-budget productions. The 2019 film Ne Zha grossed over 5 billion yuan domestically, establishing a benchmark for animated blockbusters. Its 2025 sequel, Ne Zha 2, shattered records by earning approximately 12 billion yuan (over 1.7 billion USD) worldwide, predominantly from China, surpassing Pixar's Inside Out 2 (1.66 billion USD) to become the highest-grossing animated film in history and China's top film overall.[4] [95] This achievement included the highest single-day gross for a Chinese animated film at over 700 million yuan and positioned it as the first non-Hollywood film to exceed 1 billion USD in a single territory.[96] [97] Other notable successes include the 2025 2D feature Nobody, which crossed 1 billion yuan (138.5 million USD), setting a record for domestic 2D animation earnings and topping the weekend box office during its run.[98] Earlier hits like White Snake 2: Green Snake (2021) contributed to the trend of films exceeding 100 million yuan, though such thresholds remain challenging for most releases.[99] These milestones underscore a shift toward commercially viable mythological and fantasy narratives, boosting investor confidence despite historical underperformance in the sector.[100]Major Works and Milestones

Seminal Historical Productions

Chinese animation's foundational era featured pioneering efforts by the Wan brothers, who produced the country's initial works in the 1920s, starting with advertisements such as "Shu Zhen Dong Chinese Typewriter" in 1922.[11] Their 1926 short "Uproar in the Studio" marked one of the earliest narrative animations, experimenting with cutout techniques inspired by foreign imports.[8] By 1935, the brothers advanced the medium with "The Camel's Dance," China's inaugural sound-animated film, incorporating synchronized audio to enhance storytelling amid wartime constraints.[7] The landmark "Princess Iron Fan," released in 1941, represented the first full-length animated feature in China and Asia, directed by Wan Laiming, Wan Guchan, Wan Chaochen, and Wan Dihuan.[101] Adapted from episodes in the classical novel Journey to the West, the 75-minute film depicted Sun Wukong and companions seeking a magical fan to extinguish flames blocking their path, blending cel animation with innovative styles influenced by Disney's Snow White.[101] Premiering on November 19, 1941, at Shanghai's Metropol and Astor Theatres, it drew massive crowds despite production challenges during the Sino-Japanese War, grossing significantly and establishing animation's commercial viability.[101] Post-1949 nationalization shifted production to state-backed studios, with Shanghai Animation Film Studio—formed in 1957 from earlier collectives—emerging as the epicenter.[102] The studio's "Havoc in Heaven" (1961, with Part II in 1964), directed by Wan Laiming, epitomized this phase, adapting Sun Wukong's rebellion against heavenly authority from Journey to the West.[102] Spanning over two decades in development, the hand-drawn epic employed meticulous frame-by-frame techniques, including dynamic action sequences and traditional Chinese aesthetics, completing around 100,000 drawings despite political upheavals like the Anti-Rightist Campaign.[102] Released amid the early Cultural Revolution prelude, it garnered critical acclaim for technical prowess and cultural resonance, influencing subsequent donghua while symbolizing artistic resilience.[102]Contemporary Blockbusters and Series

Ne Zha 2, released in China on January 29, 2025, stands as a landmark in Chinese animation, grossing over $2 billion worldwide and eclipsing Pixar's Inside Out 2 ($1.66 billion) to claim the title of highest-grossing animated film ever.[4] The sequel to the 2019 hit Ne Zha ($742 million worldwide) adapts elements from the mythological Investiture of the Gods, employing high-fidelity 3D CGI to depict epic battles and character arcs, and amassed $900 million in China alone within weeks of release.[103][104] Its domestic dominance reflected surging audience demand for domestic mythological narratives, bolstered by holiday timing during Chinese New Year.[105] Nobody (2025, 《浪浪山的小妖怪》), a 2D animated feature from Shanghai Animation Film Studio, achieved record box office success as China's highest-grossing 2D release, employing a retro art style with ink-wash elements, humorous and relatable content centered on underdog demons in a Journey to the West parody, and metaphors for workplace struggles of ordinary workers that resonated with domestic audiences on themes of societal pressures.[106][107] Other notable theatrical releases include Deep Sea (2023), directed by Tian Xiaopeng, which utilized groundbreaking fluid simulation techniques for underwater sequences and achieved substantial box office returns in China, contributing to the genre's growing technical sophistication.[108] Chang'an (2023) further exemplified historical fantasy animation, earning praise for its detailed Tang Dynasty recreation and strong domestic performance. Earlier entries like Jiang Ziya (2020), part of the Fengshen trilogy, grossed over $400 million, extending the mythological momentum from Ne Zha. These films highlight a shift toward big-budget productions rivaling Hollywood in scale, with budgets for Ne Zha 2 estimated at $80 million.[109][110] In television and streaming, donghua series have proliferated on platforms like Bilibili and Tencent Video, often adapting web novels in cultivation or fantasy genres. Link Click (2021–present) gained traction for its sci-fi time-travel plot, ranking among top-rated series with sustained seasons through 2023.[111] Heaven Official's Blessing (2020–2025), based on Mo Xiang Tong Xiu's novel, released multiple seasons including specials in 2023–2025, amassing high IMDb scores and international fandom via danmei adaptations.[112] Recent 2025 entries like To Be Hero X and Lord of Mysteries topped popularity metrics on IMDb, blending action and mystery elements to attract global viewers.[113] Series such as Battle Through the Heavens (ongoing since 2017, with 2023–2025 episodes) exemplify long-form serialization, drawing millions of streams through xianxia tropes of progression and combat. These productions underscore donghua's pivot to serialized content, prioritizing narrative depth over episodic formats.Reception, Critiques, and Challenges

Domestic Audience and Cultural Impact

Chinese animation, or donghua, has seen increasing engagement from domestic audiences, particularly among younger demographics. A 2025 survey by China Youth Daily of 7,232 university students found that 40.64% actively follow popular domestic animated works, with many citing improved storytelling and visual effects as key draws.[114] This reflects a shift toward greater acceptance of donghua as a mainstream entertainment form, fueled by streaming platforms like Bilibili and iQiyi, where series such as Soul Land and Heaven Official's Blessing have amassed millions of views by adapting wuxia and xianxia tropes rooted in Chinese folklore.[76] Box office successes underscore this popularity. The 2019 film Ne Zha grossed over 5 billion yuan (approximately $720 million USD), becoming China's highest-grossing animated film at the time and topping domestic animation box office records.[115] Its 2025 sequel, Ne Zha 2, shattered these benchmarks with $1.3 billion in ticket sales during the Lunar New Year period, marking the first non-Hollywood film to exceed $1 billion domestically and signaling broad family appeal through reinterpretations of classical myths.[116][97] These milestones highlight donghua's capacity to rival live-action films, with domestic animated features maintaining 60-70% of the overall animation box office share in recent years.[117] Culturally, donghua reinforces national identity by drawing on traditional elements like Journey to the West and Fengshen Yanyi, fostering appreciation for Chinese heritage among viewers.[118] Works like Ne Zha have elevated cultural literacy, portraying mythological figures in ways that resonate with modern sensibilities while preserving core values of resilience and familial duty.[45] Fan communities have evolved from passive consumption to active participation, including cosplay, fan art, and online discussions that extend narrative engagement and promote subtle transmission of aesthetic and moral frameworks aligned with Confucian influences.[119] This has contributed to a renaissance in interest for classical literature, though donghua remains somewhat niche compared to imported Japanese anime among certain urban youth cohorts.[120]International Penetration and Perceptions

Chinese animation, or donghua, has achieved limited theatrical penetration in international markets, with box office earnings predominantly concentrated in China. The 2019 film Ne Zha generated over $742 million globally, ranking as the fourth-highest-grossing animated film of that year, but its overseas revenue was modest compared to domestic figures exceeding $700 million. Similarly, the 2025 sequel Ne Zha 2 amassed $2.2 billion worldwide, yet international grosses totaled only about $60 million, representing less than 3% of its earnings and underscoring barriers such as cultural unfamiliarity with mythological narratives and insufficient localized marketing efforts.[121][122] These patterns reflect a broader trend where donghua films prioritize the vast Chinese audience over global theatrical releases, limiting exposure in regions like North America and Europe. Streaming platforms have facilitated greater accessibility, enabling niche international audiences to engage with donghua series through services like Netflix and Crunchyroll, which have licensed titles such as Link Click and Scissor Seven. This digital distribution has contributed to rising global interest, with donghua exports signaling potential for broader appeal amid increasing investments in dubbing and subtitles to bridge language gaps. However, viewership remains overshadowed by Japanese anime, which dominates platforms with established fanbases and higher subscription-driven metrics; donghua titles often attract viewers already inclined toward East Asian animation but struggle for mainstream crossover.[123][124][111] Perceptions in Western markets portray donghua as visually impressive with intricate action sequences drawn from Chinese folklore and genres like xianxia, yet frequently critiqued for stylistic similarities to anime that dilute its distinct identity. Audiences appreciate high production values in contemporary works but note challenges including culturally specific tropes that may alienate non-Chinese viewers and a perceived lack of aggressive global promotion, perpetuating a cycle of underinvestment abroad due to anticipated low returns. While some analysts highlight donghua's potential to challenge anime's hegemony through state-backed innovation, skeptics point to regulatory constraints potentially constraining narrative depth, fostering views of it as derivative rather than revolutionary.[40][76]Principal Criticisms and Debates

Chinese animation has faced significant criticism for the pervasive influence of state censorship, which mandates alterations to content deemed incompatible with official ideology, including reductions in violence, romance, and LGBTQ+ representation. For instance, the National Radio and Television Administration's review process requires donghua to pass strict ideological scrutiny, resulting in toned-down narratives that prioritize moral alignment over artistic depth, as seen in adaptations where heroines are deleted or storylines sanitized to avoid controversy. This regulatory framework, intensified since 2016 under broader cultural rectification campaigns, is argued to stifle innovation by discouraging complex themes, with producers citing it as a barrier to competing with uncensored international counterparts like Japanese anime. Critics contend that such constraints foster formulaic storytelling, contributing to audience fatigue and limited export appeal. Plagiarism allegations represent another recurrent critique, with multiple high-profile cases highlighting weak intellectual property enforcement and a culture of imitation within the industry. In 2019, the makers of the blockbuster Nezha faced a lawsuit from a Beijing production company accusing it of copying elements from their stage musical Memory, including character designs and plot motifs. Similarly, shows like Big Mouth Dudu and Windows to the Soul have been accused of lifting from Japanese classics, while a 2023 TV series drew social media backlash for apparent frame-by-frame similarities to anime originals, underscoring a perceived shortcut in creative processes amid rapid production scales. These incidents, reported in outlets like South China Morning Post and Radio Free Asia, reflect broader industry challenges, where rushed commercialization exacerbates reliance on foreign templates rather than original development, eroding trust among domestic and global viewers. Debates center on whether Chinese animation's structural limitations—rooted in state control and market dynamics—preclude it from achieving parity with Japanese anime in quality and cultural export. Proponents of progress highlight technical advancements in films like Nezha 2 (2025), which demonstrate high production values and box-office success exceeding ¥6 billion domestically, arguing that increasing investment could overcome creative bottlenecks. However, skeptics, including industry analyses, emphasize persistent issues like content homogenization and funding shortages for non-commercial works, with censorship cited as a causal factor in subdued international reception; donghua series often garner lukewarm global ratings due to perceived narrative shallowness compared to anime's thematic liberty. A 2019 University of San Francisco study attributes stalled global success to these intertwined factors, debating if liberalization or emulation of Japan's independent studio model could enable breakthroughs, though empirical data shows donghua's overseas market share remains under 5% versus anime's dominance.Emerging Trends and Outlook

Technological and Creative Advancements

Chinese animation has advanced rapidly in computer-generated imagery (CGI) and 3D modeling techniques, enabling productions with visual complexity rivaling Western counterparts. Between 2020 and 2025, studios leveraged tools such as Unreal Engine 5 and Maya to streamline workflows and achieve high-fidelity renders, as seen in blockbusters like Ne Zha 2, which utilized domestic CGI innovations to generate dynamic action sequences and detailed mythical environments.[67][125][126] The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) has further accelerated production efficiency, with generative AI applied to tasks like motion generation and visual effects. In 2023, animation houses such as Base Media began testing AI for creative augmentation, while by 2025, domestically developed models excelled at rendering Chinese cultural motifs, reducing reliance on foreign software. Techniques including AI-driven 3D human motion synthesis from text prompts have enabled more lifelike character animations, though challenges persist in maintaining artistic control amid automation.[127][128][129] Creatively, advancements have facilitated novel fusions of traditional Chinese aesthetics with digital techniques, such as ink-wash styles digitized in films like Nobody (2025), which combined hand-drawn elements with 3D for expressive storytelling exceeding 500 million RMB in revenue. This period marked a shift toward genre diversification, incorporating wuxia dynamics and folklore into 3D frameworks, enhancing narrative depth without diluting cultural specificity.[130][131] Overall, these developments, driven by state-supported R&D and market demands, positioned Chinese animation in an "advancement" phase by 2025, emphasizing scalable pipelines that balance technological precision with innovative expression.[117][74]Potential for Global Competitiveness

The Chinese animation industry, valued at approximately 24.5 billion yuan (equivalent to $3.84 billion USD) in recent comprehensive analyses, has demonstrated substantial domestic growth but faces structural barriers to achieving parity with global leaders like Japanese anime or American studios.[93] This valuation reflects heavy state-backed investments in production infrastructure and technology since the early 2010s, enabling higher output volumes—over 300,000 minutes of content annually by 2023—but export revenues remain a fraction of total earnings, estimated below 10% based on trade data patterns in cultural exports.[117] While platforms like Netflix and Crunchyroll have licensed select donghua titles such as Link Click and Scissor Seven, achieving niche audiences in Southeast Asia and the West, these do not translate to sustained box office or merchandising dominance abroad, where Japanese anime commands over 80% of the global stylized animation market share.[93] Key enablers for potential competitiveness include China's advantages in scale and technological adoption, such as AI-assisted rendering and 3D modeling, which have reduced production costs by up to 30% in state-subsidized studios since 2020.[132] Government policies under the "cultural going-out" strategy, including tax incentives and international co-production mandates, aim to boost soft power exports, with initiatives like the 2023 Belt and Road cultural forums facilitating dubbing and localization efforts.[65] Industry executives from studios like Bilibili and Tencent have projected that donghua could capture 15-20% of emerging markets in Africa and Latin America by 2030 through streaming partnerships, leveraging demographic overlaps in youth populations.[133] However, causal factors limiting breakthroughs include content homogenization—overreliance on wuxia tropes and anime stylistic mimicry without original IP development—and regulatory censorship, which prohibits themes of political dissent or moral ambiguity prevalent in successful global franchises, constraining narrative depth.[117][26] Critiques from international observers, including Japanese studio leaders, highlight donghua's risk of stagnation if it fails to prioritize universal storytelling over visual spectacle; for instance, MAPPA's producer Shigenobu Maruyama warned in 2025 that unchecked Chinese investment could eclipse anime only if accompanied by creative autonomy, which current state oversight impedes.[134] Empirical indicators of upside include breakout domestic hits like Nezha: Birth of the Demon Child (2019), which grossed $728 million primarily in China but earned $5-10 million internationally via limited releases, signaling scalability if cultural barriers are addressed through targeted adaptations.[135] Long-term viability hinges on resolving talent drain—where animators migrate to freer markets—and fostering independent voices, as systemic biases in funding toward propaganda-aligned content undermine export appeal in value-diverse regions.[136] Absent reforms, projections suggest donghua will remain a regional powerhouse rather than a global contender by 2030.[137]References

- https://www.[statista](/page/Statista).com/statistics/943698/china-total-output-value-of-animation-industry/