Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Animation studio

View on Wikipedia

An animation studio is a company producing animated media. The broadest such companies conceive of products to produce, own the physical equipment for production, employ operators for that equipment, and hold a major stake in the sales or rentals of the media produced. They also own rights over merchandising and creative rights for characters created/held by the company, much like authors holding copyrights. In some early cases, they also held patent rights over methods of animation used in certain studios that were used for boosting productivity. Overall, they are business concerns and can function as such in legal terms.

American studios

[edit]

The idea of a studio dedicated to animating cartoons was spearheaded by Raoul Barré and his studio, Barré Studio, co-founded with Bill Nolan, beating out the studio created by J.R. Bray, Bray Productions, to the honor of the first studio dedicated to animation.[1]

Though beaten to the post of being the first studio, Bray's studio employee, Earl Hurd, came up with patents designed for mass-producing the output for the studio. As Hurd did not file for these patents under his own name but handed them to Bray, they would go on to form the Bray-Hurd Patent Company and sold these techniques for royalties to other animation studios of the time.[2]

The biggest name in animation studios during this early time was Disney Brothers Animation Studio (now known as Walt Disney Animation Studios), co-founded by Walt and Roy O. Disney. Started on October 16, 1923, the studio went on to make its first animated short, Steamboat Willie in 1928, to much critical success,[3] though the real breakthrough was in 1937, when the studio was able to produce a full-length animated feature film i.e. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which laid the foundation for other studios to try to make full-length movies.[4] In 1932 Flowers and Trees, a production by Walt Disney Productions and United Artists, won the first Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film.[5] This period, from the 1920s to the 1950s or sometimes considered from 1911 to the death of Walt Disney in 1966, is commonly known as the Golden Age of American Animation as it included the growth of Disney, as well as the rise of Warner Bros. Cartoons and the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio as prominent animation studios.[6] Disney continued to lead in technical prowess among studios for a long time afterwards, as can be seen with their achievements. In 1941, Otto Messmer created the first animated television commercials for Botany Tie ads/weather reports. They were shown on NBC-TV in New York until 1949.[2] This marked the first forays of animation designed for the smaller screen and was to be followed by the first animated series specifically made for television, Crusader Rabbit, in 1948.[7][better source needed] Its creator, Alex Anderson, had to create the studio 'Television Arts Productions' specifically for the purpose of creating this series as his old studio, Terrytoons, refused to make a series for television. Since Crusader Rabbit, however, many studios have seen this as a profitable enterprise and many have entered the made for television market since, with Joseph Barbera and William Hanna refining the production process for television animation on their show Ruff and Reddy. It was in 1958 that The Huckleberry Hound Show claimed the title of being the first all-new half-hour cartoon show. This, along with their previous success with the series Tom and Jerry, elevated their animation studio, H.B. Enterprises (later Hanna-Barbera Productions), to dominate the North American television animation market during the latter half of the 20th century.[8]

In 2002, Shrek, produced by DreamWorks and Pacific Data Images won the first Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.[9] Since then, Disney/Pixar have produced the most number of movies either to win or be nominated for the award.[10]

Direct-to-video market

[edit]Though the term "direct-to-video" carries negative connotations in the North American and European markets, direct-to-video animation has seen a rise, as a concept, in the Western markets. With many comic characters receiving their versions of OVA's, original video animations, under the Westernized title of direct-to-video animations, the OVA market has spread to American animation houses. Their popularity has resulted in animated adaptations of comic characters ranging from Hellboy, Green Lantern and Avengers. Television shows such as Family Guy and Futurama also released direct-to-video animations. DC Comics have continually released their own animated movies for the sole purpose of sale in the direct-to-video market. With growing worries about piracy, direct to video animation might become more popular in the near future.[11]

Ownership trends

[edit]With the growth of animation as an industry, the trends of ownership of studios have gradually changed with time. Current studios such as Warner Bros. and early ones such as Fleischer Studios, started life as small, independent studios, being run by a very small core group. After being bought out or sold to other companies, they eventually consolidated with other studios and became larger. The drawback of this setup was that there was now a major thrust towards profitability with the management acting as a damper towards creativity of these studios, continuing even in today's scenario.[12]

Currently, the independent animation studios are looking to ensure artistic integrity by signing up with big animation studios on contracts that allow them to license out movies, without being directed by the bigger studios. Examples of such co-operation are the joint ventures between DreamWorks and Paramount Pictures and that of Blue Sky Studios and 20th Century Studios.

On August 22, 2016, Comcast's NBCUniversal acquired DreamWorks Animation, appointing Meledandri oversee Comcast's Universal Animation/DreamWorks/Illumination, Disney's Disney Animation/Pixar/20th Century Animation, & Warner Bros. Warner Bros. Animation/Warner Bros. Pictures Animation.

Japanese studios

[edit]

The first known example of Japanese animation, also called anime, is dated around 1917,[13] but it would take until 1956 for the Japanese animation industry to successfully adopt the studio format as used in the United States. In 1961, these productions began to be aired in the US. Toei Animation, formed in 1948, was the first Japanese animation studio of importance and saw the reduction of animators as independent anime artists.

After the formation of Toei Animation Co. Ltd. in 1948, the Japanese studios churned out minor works of animation. But with the release of Toei's first theatrical feature, The Tale of the White Serpent released in October 1958,[14][failed verification] the animation industry in Japan came into the eye of the general public.

The success of Alakazam the Great led to the finding of the artist Osamu Tezuka, who would go on to become the father of Japanese manga with his brand of modern, fast-paced fantasy storylines. He became influenced by Hanna-Barbera productions of the late 1950s and made Japan's first made for television animation studio, Mushi Productions. The success of the studios' first show in 1963, Astro Boy, was so immense that there were 3 other television animation studios by the end of the year and Toei had opened their own made for television division. The greatest difference between Japanese studios and North American studios was the difference in adult-themed material to make way in Japan. Tezuka's thought that animation should not be restricted to kids alone has brought about many studios that are employed in the production of adult-themed adaptations of classic stories such as Heidi (Heidi, Girl of the Alps), One Thousand and One Nights and The Diary of a Young Girl and many more.

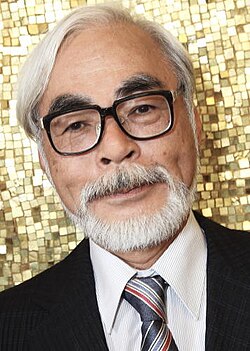

In the 1980s, animation studios were led back to their theatrical roots due to the success of Hayao Miyazaki's film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which led publishing house Tokuma Shoten to finance a new animation studio, Studio Ghibli, which would be used for the personal works of Miyazaki and his close friend, Isao Takahata. Many of Ghibli's works have become Japan's top-grossing theatrical films, whether in live-action or animated form.

OAV/OVA market

[edit]The market for 'OAV's or 'Original Anime Video' later the acronym would be better known as 'OVA' meaning 'Original video animation' as the term 'OAV' could often be misunderstood for 'Original Adult Video', began in 1984. These are often tended towards the home video market, while not tending to the television or theatrical audience as such. They refer to those movies that are launched as direct-to-video releases and not meant to be released in theatres. Video productions can run from half an hour productions to well over two hours. They require that premise or story be original in order to be counted as an OVA, though sometimes, the story can be derived from a longer running manga or animated series. As the OAV market is not adapted to the rigors that are faced by television shows or feature films, they have been known to show gratuitous amounts of violence and/or pornography. Some OAV's have registered such strong acclaim that they have been remade as anime television series as well as theatrical releases.

Since most new OVA's are derived from other animated media, many animation studios that have previously worked on animated series or movies, and adaptations of Japanese manga, have now entered the OVA market, looking to capitalize on the popularity of their flagship shows. Studios participating in such circumstances include Production I.G and Studio Deen.

Animator's contracts

[edit]Although there are permanent/full-time positions in studios, most animators work on a contract basis. There are some animators that are considered to be in the core group of the studio, which can either be as a result of being there since the inception of the company or being talented recruits from other animation studios. These are the more secure positions in an animation studio, though the studio might have policies concerning the possible tenure of animators. Since studios can hire animators on a work for hire basis nowadays, many artists do not retain rights over their creations, unlike some of the early animators. The extent of these copyrights is subject to local intellectual property rights.

The animators must also be aware of the contracts laws and labour laws prevalent in the jurisdiction to which the animation studio is subject to. There have been numerous legal battles fought over the copyright of famous franchises, such as Kung Fu Panda[15] and SpongeBob SquarePants. This has come about as a result of the clause in Copyright contracts that states that an idea cannot be protected, only an actual piece of work can be said to be infringed upon. This means that though the animators may have forwarded ideas to the animation studios about certain characters and plots, these ideas alone cannot be protected and can lead to studios profiting on individual animator's ideas. However, this has not stopped many independent artists from filing claims to characters produced by different studios.[16]

Animation specialties

[edit]

Due to the wide range of animation techniques and styles, many animation studios typically specialize in certain types.

Traditional animation

[edit]Traditional animation employs the use of hand-drawn frames, and is used in the world of cartoons and anime. Notable studios that specialize in this style include Walt Disney Animation Studios, Studio Ghibli, Cartoon Saloon, Nickelodeon Animation Studio, Disney Television Animation, 20th Television Animation, Warner Bros. Animation, Cartoon Network Studios, Titmouse, Ufotable, Studio Chizu and CoMix Wave Films.

Stop-motion animation

[edit]Stop-motion animation uses objects that are incrementally moved and photographed in order to create an illusion of movement when the resulting frames are played back. Notable studios specializing in this style of animation include Aardman Animations, Laika Rankin/Bass Animated Entertainment and ShadowMachine.

3D computer animation

[edit]3D animation is the newest of the animation techniques, using the assistance of computers and software, such as Houdini, to create 3D models that are then manipulated and rendered to create movement. Notable studios include Pixar Animation Studios, DreamWorks Animation, Sony Pictures Imageworks, Blue Sky Studios, Illumination, DNEG and Marza Animation Planet.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Crandol, Michael (1999). "The History of Animation: Advantages and Disadvantages of the Studio System in the Production of an Art Form". Digital Media FX. Archived from the original on August 21, 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ a b Cohen, Karl (January 2000). "Milestones Of The Animation Industry In The 20th Century". Animation World Magazine. 4 (10). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Karl (January 2000). "Milestones Of The Animation Industry In The 20th Century". Animation World Magazine. 4 (10). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Karl (January 2000). "Milestones Of The Animation Industry In The 20th Century". Animation World Magazine. 4 (10). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Waheed, Mazher (21 March 2011). "Flowers and Trees [1932], 1st Oscar Award Winner 3D Animation Movie". Free Maya Video Tutorials. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503759-6.

- ^ "Crusader Rabbit". Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2011 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Farley, Ellen (1985-03-08). "Saturday Morning Turf Now Being Invaded : Hanna, Barbera Turned Firing Into Triumph". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Grebey, James (6 February 2020). "Every Academy Awards Best Animated Feature Winner, Ranked". GQ. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved 2020-02-09.

- ^ "Academy Awards: Every Non-Pixar Film To Win Best Animated Feature". ScreenRant. 2020-02-06. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved 2020-02-09.

- ^ Rorie, Matt (12 October 2011). "How Tower Heist Could Have Changed The Way You Watch Movies (But Won't)". Screened. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012.

- ^ McKay, Hollie (2011-07-15). "Is Hollywood Ruining Children's Movies With Adult-Focused Content?". Fox News. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011.

- ^ Cooper, Lisa Marie. "Global History of Anime". Right Stuf. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved 2020-02-09.

- ^ "Literature Study Guides - By Popularity - eNotes.com". eNotes. Archived from the original on October 19, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Goldberg, Andrew (May 26, 2011). "Copyright Suits Can't Keep Potential Blockbusters Out of Theaters". The American Lawyer. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ "Faerie Media Animation". Faerie Media Animation. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

Animation studio

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Overview

Definition and Role

An animation studio is a company or organization dedicated to the production of animated media, including films, television series, commercials, and digital content, utilizing techniques ranging from traditional hand-drawn methods to computer-generated imagery. These studios serve as creative hubs where ideas are conceptualized, developed, and brought to life through collaborative workflows, often owning or accessing specialized equipment and software essential for the process.[7][8] The primary roles of an animation studio revolve around the three core phases of production: pre-production, production, and post-production, with teams comprising writers, directors, storyboard artists, animators, and technical specialists working in tandem. In pre-production, studios focus on scripting, storyboarding, character design, and planning, establishing the project's narrative foundation and budget while collaborating with clients or broadcasters to align on vision and timelines. Production involves the actual creation of animation, where animators generate frames or 3D models using tools like drawing tables for traditional work, lightboxes, pencils, or digital software such as Adobe Animate, Toon Boom Harmony, Blender, and Autodesk Maya; this phase requires coordinated teams to handle modeling, rigging, texturing, lighting, and keyframe animation. Post-production encompasses editing sequences, adding sound design, visual effects, color correction, and final rendering to produce polished outputs ready for distribution.[9][10][8][11] Key operational elements include multidisciplinary teams that ensure seamless collaboration, from creative directors overseeing artistic direction to producers managing resources and deadlines, often supported by equipment like high-performance computers, graphics tablets, and rendering farms for efficient output. Animation studios deliver diverse formats, such as theatrical feature films exemplified by Walt Disney Animation Studios' classics like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), which pioneered full-length animated storytelling, or short-form advertisements tailored for brands and streaming platforms. These roles extend to client partnerships, where studios adapt content for specific media, emphasizing innovation in techniques to meet evolving industry demands.[9][12]Historical Development

The origins of animation studios trace back to the 1910s and 1920s, when pioneering animators experimented with hand-drawn techniques to create short films for vaudeville and early cinema. Winsor McCay, a prominent newspaper cartoonist, produced groundbreaking works like Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), which demonstrated frame-by-frame drawing on paper to achieve fluid motion, marking one of the first instances of character-driven animation.[13] In parallel, the Fleischer Brothers, Max and Dave, established their studio in 1921, innovating with the rotoscope device to trace live-action footage onto animation cels, enabling more realistic human movements in shorts such as Out of the Inkwell series (1918–1929).[14] These early studios relied entirely on manual labor-intensive processes, including pencil sketches, inking, and painting on transparent celluloid sheets, laying the foundation for commercial animation production.[15] The 1930s to 1950s represented the Golden Age of animation studios, characterized by the rise of major Hollywood entities that elevated the medium through synchronized sound, color, and narrative sophistication. Walt Disney Productions led this era with innovations like the multiplane camera for depth effects and the first full-length animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), which premiered on December 21, 1937, and grossed over $8 million in its initial release, proving the viability of feature-length animation.[16] Other studios, such as Warner Bros. and MGM, contributed with iconic short series like Looney Tunes and Tom and Jerry, employing larger teams of specialized artists to produce hundreds of films annually.[17] This period saw studios standardize workflows, including storyboarding and voice recording, transforming animation from novelty acts into a cornerstone of the film industry.[18] Following World War II, animation studios expanded significantly in the 1960s through 1980s, driven by the boom in television programming and cost-efficient production methods. Hanna-Barbera Productions, founded in 1957 by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera after leaving MGM, pioneered limited animation techniques—reusing cels and minimizing movement—to create affordable TV series, exemplified by The Flintstones (1960–1966), the first prime-time animated sitcom that aired for six seasons and influenced family-oriented broadcast content.[19] This shift enabled studios to produce hundreds of episodes yearly, with Hanna-Barbera alone outputting over 100 series by the 1980s, including The Jetsons (1962–1963) and Scooby-Doo (1969 onward), which incorporated international distribution and adaptations.[20] International influences grew as U.S. studios licensed formats abroad, fostering cross-cultural exchanges in storytelling and style.[21] The digital transition from the 1990s onward revolutionized animation studios through the adoption of computer-generated imagery (CGI), shifting from analog to digital pipelines for modeling, rendering, and compositing. Pixar Animation Studios marked this era with Toy Story (1995), the first entirely computer-animated feature film, produced using proprietary software like RenderMan to create 114,240 unique frames over four years, grossing $373 million worldwide and establishing CGI as a dominant format.[22][23] This milestone prompted traditional studios like Disney to integrate digital tools, reducing production times and enabling complex simulations unattainable with hand-drawn methods.[24] Parallel to these advancements, the global spread of animation studios accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s with the emergence of non-Western entities, diversifying styles and markets beyond Hollywood dominance. In Japan, Toei Animation expanded TV production in the 1970s, adapting manga into series like Mazinger Z (1972–1974), which popularized mecha genres and exported to over 50 countries by 1978, contributing to anime's international breakthrough.[25] Similarly, China's Shanghai Animation Film Studio revived post-Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s, releasing 288 works by 1994, including innovative ink-wash animations like The Legend of the White Snake (1980s reworks), though it faced competition from foreign imports.[26] These developments set the stage for regional diversification, with Japan's Studio Ghibli, founded in 1985, producing acclaimed features such as Castle in the Sky (1986), blending Eastern aesthetics with global appeal. In the 2000s, the CGI revolution continued with studios like DreamWorks Animation achieving success with Shrek (2001), which grossed over $484 million worldwide and won the first Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, further entrenching computer animation in mainstream cinema.[27]Types of Animation Studios

Independent vs. Corporate Studios

Independent animation studios are typically self-funded or small-scale operations that maintain ownership and creative decision-making outside of large corporate structures, allowing for focused experimentation in techniques like stop-motion.[28] For instance, Laika Studios emphasizes bold, original storytelling through a blend of artistry and technology, fostering an environment where creators enjoy significant freedom to shape their careers without mimicking mainstream approaches.[29] This autonomy enables independent studios to pursue niche projects that prioritize artistic innovation over broad commercial appeal, often resulting in critically acclaimed works that stand out in specialized markets.[30] The primary advantages of independent studios include heightened artistic control and the flexibility to explore unconventional narratives, which can lead to unique visual styles and direct audience engagement via platforms like YouTube.[31] These operations benefit from lower overheads and nimble production processes, enabling quicker adaptation to new technologies and international co-productions that expand creative and financial opportunities.[30] However, challenges abound, including funding instability due to reliance on limited budgets and the difficulty of securing distribution in markets dominated by major releases.[30] Independent studios often face crowded theatrical schedules and high production costs, compounded by uncertainties in streaming and emerging technologies like AI, which can strain resources without the safety net of corporate backing.[30] In contrast, corporate animation studios operate under the umbrella of large conglomerates, integrating production with broader media empires to leverage extensive infrastructure and distribution networks.[32] Disney's acquisition of Pixar in 2006 exemplifies this model, providing access to proprietary 3D animation expertise and generating billions in revenue through synergistic marketing and global reach.[32] Benefits include substantial resources for high-budget projects, reduced risks via diversified portfolios, and the ability to produce blockbuster films that dominate box offices, as seen in Disney's vertical integration strategy that turned uncertain technologies into industry standards.[32] Corporate studios, however, grapple with commercial pressures that prioritize profitability and franchise continuity, often constraining creative risks in favor of formulaic IP extensions.[32] This can lead to high production costs, often $200–300 million per film (as of 2025), and dependency on hit-driven outcomes, limiting flexibility and fostering a pace that may stifle innovation.[32][33] Intellectual property constraints further bind creators to established brands, potentially diluting original storytelling in pursuit of shareholder expectations. A notable case of independent success is Aardman Animations, which has sustained its autonomy through award-winning stop-motion films like Chicken Run, maintaining integrity, excellence, and humor while exercising unusual control over its affairs without shareholder interference.[34] Conversely, DreamWorks Animation's corporate evolution—from its 1994 founding as part of DreamWorks SKG to becoming a public entity in 2004 and later Universal's subsidiary—illustrates how affiliation with conglomerates enabled scaled production of hits like Shrek but shifted focus toward franchise-driven output amid industry consolidations.[35] Emerging hybrid models blend independence with corporate partnerships through co-productions, allowing studios like Aardman to collaborate with entities such as DreamWorks on films like Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, combining creative autonomy with enhanced funding and distribution.[36] Platforms like Netflix further exemplify this by partnering with independent teams for global projects, mitigating funding risks while preserving niche artistic visions.[37]| Aspect | Independent Studios | Corporate Studios |

|---|---|---|

| Creative Control | High; focus on original, niche stories (e.g., Laika's stop-motion innovation) | Moderate; influenced by commercial and IP priorities (e.g., Disney's franchise emphasis) |

| Resources & Reach | Limited budgets but nimble; direct platforms for engagement | Vast funding and global distribution; blockbuster potential |

| Challenges | Funding instability, distribution barriers | Pressures for profitability, reduced flexibility |

| Examples | Aardman (autonomous awards success) | DreamWorks (corporate scaling via acquisitions) |

.jpg/250px-Disney_Animation_Building_Burbank_(51080194402).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Disney_Animation_Building_Burbank_(51080194402).jpg)