Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pyomyositis

View on Wikipedia| Pyomyositis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tropical pyomyositis or Myositis tropicans |

| |

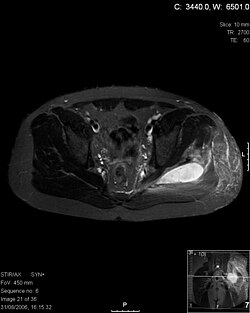

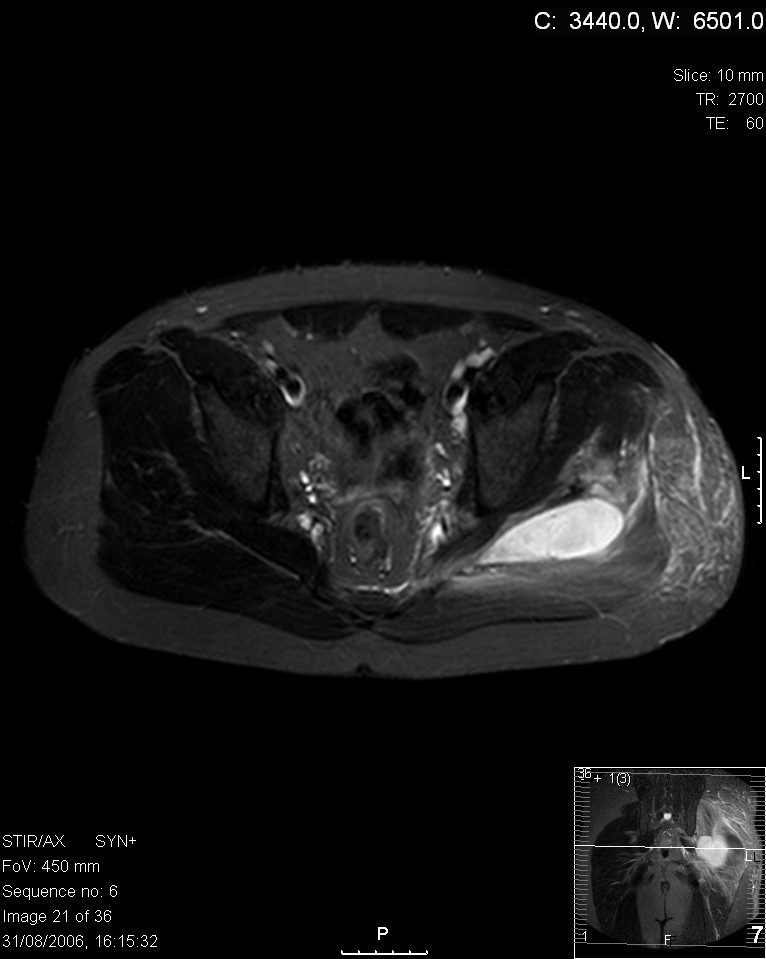

| Transverse T2 magnetic resonance imaging section through the hip region showing abscess collection in a patient with pyomyositis. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Diagnostic method | Diagnostic method used for PM includes ultrasound, CT scan and MRI. Ultrasound can be helpful in showing muscular heterogeneity or a purulent collection but it is not useful during the first stage of the disease. CT scan can confirm the diagnosis before abscesses occur with enlargement of the involved muscles and hypodensity when abscess is present, terogenous attenuation and fluid collection with rim enhancement can be found. MRI is useful to assess PM and determine its localization and extension |

Pyomyositis (Myositis tropicans) is a bacterial infection of the skeletal muscles which results in an abscess. Pyomyositis is most common in tropical areas but can also occur in temperate zones.

Pyomyositis can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary pyomyositis is a skeletal muscle infection arising from hematogenous infection, whereas secondary pyomyositis arises from localized penetrating trauma or contiguous spread to the muscle.[1]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis is done via the following manner:[2]

- Pus discharge culture and sensitivity

- X ray of the part to rule out osteomyelitis

- Creatinine phosphokinase (more than 50,000 units)

- MRI is useful

- Ultrasound guided aspiration

Bioptates of affected muscle tissues show acute and chronic inflammatory cells, and in one case caused by influenza A infection muscle cells show lack of nuclei.[3]

Symptoms

[edit]Pyogenic symptoms usually are present in the following muscles:[4]

- serratus anterior

- pectoralis major

- biceps

- abdominal muscles

- spinal muscles

- glutei

- iliopsoas

- quadriceps

- gastrocnemicus

The course of this disease is divided into three distinct phases. The invasive stage manifests as general muscle soreness and swelling without erythema and low-grade fever and lasts about ten days. The purulent-suppurative stage occurs after about 2–3 weeks and is associated with increased body temperature and muscle tenderness. In the third stage, sepsis occurs that can lead to serious complications, including death.[4]

Treatment

[edit]The abscesses within the muscle must be drained surgically (not all patients require surgery if there is no abscess). Antibiotics, such as vancomycin, teicoplanin, tigecycline, daptomycin or linezolid are given for a minimum of three weeks to clear the infection.[5][4] In some cases, co-trimoxazole is sufficient.[4]

Epidemiology

[edit]Pyomyositis is most often caused by the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus.[6] The infection can affect any skeletal muscle, but most often infects the large muscle groups such as the quadriceps or gluteal muscles.[5][7][8]

Pyomyositis is mainly a disease of children and was first described by Scriba in 1885. Most patients are aged 2 to 5 years, but infection may occur in any age group.[9][10] Infection often follows minor trauma and is more common in the tropics, where it accounts for 4% of all hospital admissions. In temperate countries such as the US, pyomyositis was a rare condition (accounting for 1 in 3000 pediatric admissions), but has become more common since the appearance of the USA300 strain of MRSA.[5][7][8]

Pyomyositis is inherently related to residency in tropical areas, especially in northern Uganda, where yearly about 400-900 cases are reported.[4] In these regions, the general population affected by this disease is not affected by other concommitant diseases. However, in temperate regions pyomyositis is usually present in immunocompromised indiviiduals or people affected by chronic renal failure or rheumatoid arthritis.[4]

Gonococcal pyomyositis is a rare infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae.[11]

| Bacteria | Fungi | Parasites | Viruses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | Gram-negative | Anaerobes | Atypical bacteria | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Note: ★★★ – most common pathogens, ★★ – occasionally cause pyomyositis, ★ – rare pathogens | ||||||

Additional images

[edit]-

CT with IV contrast showing enlargement and heterogeneous hypodensity in the right pectoralis major muscle. A focal abscess collection with gas within it is present medially. There are enlarged axillary lymph nodes and some extension into the right hemithorax. Note the soft tissue and phlegmon surrounding the right internal mammary artery and vein. The patient was HIV+ and the pyomyositis is believed to be due to direct inoculation of the muscle related to parenteral drug abuse. The patient admitted to being a "pocket shooter"

-

CT exam showing a multiloculated fluid collection in the left gluteus minimus muscle found to be a staph aureus pyomyositis in a 12-year-old healthy boy.

-

Axial T1 weighted fat suppressed post IV gadolinium contrast enhanced MRI image showing a mutliloculated bacterial abscess in the left gluteal muscle which grew Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin sensitive) thought to be due to tropical pyomyositis.

-

Coronal fat suppressed post contrast image showing a multiloculated bacterial abscess in the left gluteus minimus muscle due to tropical pyomyositis.

-

Coronal T2 weighted fat suppressed image showing a multiloculated fluid collection in the left gluteal musculature due to tropical pyomositis in a 12-year-old boy.

References

[edit]- ^ "Primary pyomyositis". UpToDate. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Orphanet: Pyomyositis". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2025-07-13.

- ^ Radcliffe, Christopher; Gisriel, Savanah; Niu, Yu Si; Peaper, David; Delgado, Santiago; Grant, Matthew (2021-04-01). "Pyomyositis and Infectious Myositis: A Comprehensive, Single-Center Retrospective Study". Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 8 (4) ofab098. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab098. ISSN 2328-8957. PMC 8047863. PMID 33884279.

- ^ a b c d e f "Orphanet: Pyomyositis". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 13 July 2025.

- ^ a b c Pannaraj PS, Hulten KG, Gonzalez BE, Mason EO Jr, Kaplan SL (2006). "Clin Infect Dis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (8): 953–60. doi:10.1086/507637. PMID 16983604.

- ^ Chauhan S, Jain S, Varma S, Chauhan SS (2004). "Tropical pyomyositis (myositis tropicans): current perspective". Postgrad Med J. 80 (943): 267–70. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2003.009274. PMC 1743005. PMID 15138315.

- ^ a b Ovadia D, Ezra E, Ben-Sira L, et al. (2007). "Primary pyomyositis in children: a retrospective analysis of 11 cases". J Pediatr Orthop B. 16 (2): 153–159. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e3280140548. PMID 17273045.

- ^ a b Mitsionis GI, Manoudis GN, Lykissas MG, et al. (2009). "Pyomyositis in children: early diagnosis and treatment". J Pediatr Surg. 44 (11): 2173–178. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.053. PMID 19944229.

- ^ Small LN, Ross JJ (2005). "Tropical and temperate pyomyositis". Infect Dis Clin North Am. 19 (4): 981–989. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2005.08.003. PMID 16297743.

- ^ Taksande A, Vilhekar K, Gupta S (2009). "Primary pyomyositis in a child". Int J Infect Dis. 13 (4): e149 – e151. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2008.08.013. PMID 19013093.

- ^ Jensen M (2021). "Neisseria gonorrhoeae pyomyositis complicated by compartment syndrome: A rare manifestation of disseminated gonococcal infection". IDCases. 23 e00985. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00985. PMC 7695882. PMID 33294370.

- ^ Crum-Cianflone, Nancy F. (July 2008). "Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (3): 473–494. doi:10.1128/CMR.00001-08. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 2493084. PMID 18625683.

- Maravelas R, Melgar TA, Vos D, Lima N, Sadarangani S (2020). "Pyomyositis in the United States 2002-2014". J Infect. 80: 497–503. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.005. PMID 32147332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link).

External links

[edit]Pyomyositis

View on GrokipediaBackground

Definition

Pyomyositis is a primary bacterial infection of skeletal muscle characterized by subacute onset and progression to localized abscess formation within the muscle tissue, typically arising via hematogenous seeding rather than contiguous spread from adjacent structures.[4][5][6] This condition leads to pus accumulation in the affected striated muscles, distinguishing it as a suppurative process confined to the skeletal musculature.[2] Unlike infectious myositis, which encompasses diffuse muscle inflammation caused by various infectious agents without obligatory abscess development, pyomyositis specifically involves discrete, pus-filled collections that evolve over days to weeks.[2] It also differs from secondary pyomyositis, where muscle involvement occurs as an extension from nearby sites of infection, such as osteomyelitis or soft tissue abscesses.[6] The term pyomyositis, also known as tropical pyomyositis or myositis tropicans, reflects its historical association with endemic occurrence in tropical climates, though it is now increasingly documented in temperate regions globally.[2][7]History

Pyomyositis was first mentioned in the mid-19th century in temperate climates, with early cases described in Europe by pathologists such as Rudolf Virchow, who noted spontaneous acute myositis in 1852.[8] However, the condition received its detailed clinical characterization as a distinct entity in 1885 by German surgeon Justus Scriba, who reported cases in Japan and emphasized its prevalence as an endemic disease in tropical regions, leading to its alternative name, myositis tropicans.[8] Scriba's work highlighted the suppurative nature of intramuscular abscesses, distinguishing it from other soft-tissue infections.[9] In the early 20th century, as European colonial expansion brought more medical observations from tropical areas, pyomyositis was increasingly documented in Africa, the Pacific islands, and Southeast Asia, solidifying its association with humid, high-temperature environments.[8] This period marked the recognition of pyomyositis as a primarily tropical infection, with bacteriological studies beginning to identify Staphylococcus aureus as a key pathogen, though isolation techniques were rudimentary. By the mid-20th century, isolated non-tropical cases began to emerge, challenging the disease's exclusive tropical linkage, though they remained rare and often overlooked. The first well-documented report in North America appeared in 1971, involving a child in Massachusetts without travel history to endemic areas.[10] The 1980s HIV/AIDS epidemic further propelled recognition of pyomyositis in temperate zones, as immunosuppression emerged as a critical risk factor; multiple cases were reported in HIV-positive individuals starting in 1986, with S. aureus infections complicating advanced disease stages.[2] This era saw a surge in literature linking the condition to underlying immunocompromise, expanding diagnostic awareness beyond geographic confines. In recent decades, pyomyositis incidence has risen in temperate regions, attributed to factors such as intravenous drug use, diabetes mellitus, and other immunocompromising conditions, with U.S. hospitalizations increasing threefold from 2002 to 2014.[2] Cases linked to injection drug use, often involving multifocal abscesses from contaminated needles, have been highlighted in reviews since the 1990s. Similarly, diabetes has been associated with higher susceptibility, particularly in adults, reflecting broader epidemiological shifts toward chronic comorbidities in non-tropical settings.[11] While direct ties to climate change or migration remain underexplored in primary literature, increased global travel and population movements from endemic areas may contribute to sporadic reports in urban centers.[8]Epidemiology

Distribution and incidence

Pyomyositis is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions, including tropical Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific Islands, where it represents a significant cause of morbidity among otherwise healthy individuals.[12] In these areas, the disease accounts for 1-4% of hospital admissions related to fever or surgical interventions, with higher rates observed in resource-limited settings such as parts of Africa and Asia.[13][14] In temperate climates, such as North America and Europe, pyomyositis remains rare, with an estimated incidence of approximately 0.5 cases per 100,000 person-years.[15] Historical data indicate only about 98 cases reported in North America between 1971 and 1992, though recent studies show a threefold increase in hospitalizations in the United States from 2002 to 2014, attributed to rising immigration from endemic areas, increasing comorbidities like diabetes and HIV, and improved diagnostic awareness.[16][14] Seasonal patterns are prominent in tropical regions, with cases peaking during rainy and hot seasons, often linked to increased minor trauma, insect bites, and humidity facilitating bacterial entry through skin breaches; for instance, in northern India, most occurrences cluster from July to October.[8] In contrast, no distinct seasonality has been observed in temperate zones.[3] As of 2025, global trends reflect persistent underreporting in low-resource tropical settings, where limited surveillance hampers accurate estimation, though the disease's recognition continues to grow in temperate regions due to globalization and vulnerable populations.[16]Affected populations

Pyomyositis predominantly affects children and young adults, exhibiting a bimodal age distribution with peaks among children aged 2 to 5 years and young adults aged 20 to 45 years.[17] In tropical regions, the majority of cases occur in individuals under 20 years of age, particularly children, reflecting the disease's endemic nature in these settings.[18] The condition is uncommon in the elderly, occurring rarely unless underlying immunosuppression is present.[15] Males experience pyomyositis at a higher rate than females, with a male-to-female ratio ranging from 2:1 to 3:1, potentially attributable to increased exposure to trauma and outdoor activities among men.[15][19] Socioeconomic factors play a substantial role, as the disease shows elevated incidence in low-income, rural communities within tropical areas, where limited access to healthcare exacerbates its impact on affected populations.[18] Indigenous populations in Australia and the Pacific region face a disproportionate burden, consistent with higher rates of Staphylococcus aureus infections in these groups.[20] Among special populations, pyomyositis is increasingly observed in HIV-positive individuals, with a meta-analyzed odds ratio of 4.82 (95% CI: 1.67–13.92) indicating strong association, particularly in endemic tropical areas where immune compromise heightens vulnerability.[18] Cases are also rising among diabetics and intravenous drug users in urban temperate settings, driven by comorbidities and injection-related bacteremia that facilitate muscle infections.[21][22]Etiology

Pathogens

The primary causative agent of pyomyositis is Staphylococcus aureus, which accounts for 75-90% of cases worldwide, with higher rates observed in tropical regions (up to 90%) compared to temperate climates (around 75%).[23][24] Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), particularly community-acquired strains, has emerged as a significant contributor in temperate areas, comprising 20-50% of S. aureus cases in some series, often associated with more severe presentations.[25][26] Other bacterial pathogens are less common, with Streptococcus species (including group A Streptococcus) responsible for approximately 5-10% of infections, typically in cases with contiguous spread from skin or soft tissue sources. Kingella kingae is an occasional cause in children, particularly in temperate regions.[26][2] Gram-negative rods, such as Escherichia coli, account for about 5% of cases and are more frequently encountered in patients with diabetes mellitus, where they may exploit impaired host defenses.[27] Anaerobic bacteria, including Clostridium species, occasionally contribute to polymicrobial infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or those with penetrating trauma.[1] Rare etiologic agents include Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which predominates in endemic regions and immunocompromised hosts, often presenting as chronic or multifocal disease.[26] Fungal pathogens, such as Candida species, are exceptional causes, almost exclusively in patients with severe immunosuppression, such as those with advanced HIV or undergoing chemotherapy.[28] Key virulence factors of S. aureus in pyomyositis include toxins like Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a pore-forming leukotoxin that lyses neutrophils and macrophages, thereby promoting muscle necrosis, abscess formation, and dissemination; PVL-positive strains increase the odds of pyomyositis by over 100-fold compared to PVL-negative isolates.[29]Risk factors

Pyomyositis susceptibility is heightened by various immunosuppressive conditions that impair the host's ability to combat bacterial invasion of skeletal muscle. HIV infection significantly increases risk, with a meta-analysis reporting an odds ratio of 4.82 (95% CI: 1.67–13.92), and advanced AIDS showing an even stronger association at an odds ratio of 6.08 (95% CI: 2.79–13.25).[30] Diabetes mellitus, both type 1 and type 2, is linked to elevated odds of pyomyositis through mechanisms involving impaired immune response and vascular complications.[31] Chemotherapy for malignancies, such as hematologic cancers, further compromises immunity, leading to cases of pyomyositis during neutropenic phases.[32] Similarly, sickle cell disease predisposes individuals due to chronic immune dysregulation and recurrent vaso-occlusive events that damage muscle tissue.[33] Trauma and breaches in skin or muscle integrity facilitate direct bacterial inoculation, particularly in temperate climates where these factors predominate. Muscle injury from accidents or strenuous activity occurs in 25–50% of cases, providing a portal for pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus, the most common causative agent.[24] Insect bites have been implicated as entry points, especially in tropical settings where they contribute to bacteremia leading to muscle abscesses.[34] Intravenous drug use is a key modifiable risk in non-tropical regions, often resulting in hematogenous spread or direct injection-site contamination, and is associated with up to 30% of cases in such areas through repeated skin punctures.[35] Environmental factors, prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions, exacerbate vulnerability by weakening overall health and immunity. Malnutrition, particularly protein-calorie deficiency, is the most common risk factor globally, frequently observed in endemic tropical areas where it underlies many cases among otherwise healthy children and young adults.[36] Poor hygiene and overcrowding promote bacterial colonization and transmission, amplifying exposure in resource-limited settings.[37] Additional risks include concurrent infections that transiently suppress immunity, such as viral or parasitic diseases, with strenuous physical activity in hot climates further predisposing athletes or laborers by causing microtrauma in already stressed muscles.[14][38]Pathogenesis

Mechanisms of infection

Pyomyositis primarily establishes through hematogenous seeding of bacteria into skeletal muscle during transient episodes of bacteremia, which accounts for the majority of cases. This route is often preceded by minor muscle trauma, reported in 25 to 50 percent of patients, creating a vulnerable site for bacterial lodgment. Less commonly, direct inoculation occurs via penetrating injuries or extension from contiguous skin and soft tissue infections.[1][39][2] Skeletal muscle's rich vascularity and robust immune surveillance typically confer resistance to infection, but trauma disrupts this barrier, establishing a locus minoris resistentiae that facilitates bacterial adhesion. Pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus employ surface adhesins to bind damaged muscle fibers, while ischemia induced by injury generates a low-oxygen niche ideal for anaerobic proliferation and early abscess initiation.[39][1][40] Once established, S. aureus evades innate immunity by forming protective biofilms and secreting proteases that degrade extracellular matrix and muscle tissue. The subsequent neutrophil influx exacerbates tissue damage through release of reactive oxygen species, leading to liquefaction necrosis. Local hypoxia and acidosis further promote bacterial growth and suppuration, amplifying the infectious process.[39][1][41]Stages of pyomyositis

Pyomyositis progresses through three distinct stages if left untreated, characterized by escalating pathological changes in the infected skeletal muscle. The invasive stage, also known as stage 1 or the subacute phase, typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks and involves initial bacterial invasion leading to localized muscle inflammation without abscess formation. During this phase, the affected muscle becomes indurated with a "woody" texture, tender to palpation, and exhibits edema and inflammatory infiltrates, but no pus collection is present; mild systemic symptoms such as low-grade fever and malaise may accompany these changes.[1][40] The suppurative stage, or stage 2, follows and generally spans 10 to 21 days, marked by the development of a focal intramuscular abscess with accumulation of purulent material. Pathologically, this involves neutrophil-rich infiltrates, muscle fiber necrosis, and surrounding fibrosis, resulting in pronounced muscle swelling, increased tenderness, and fluctuance upon examination; aspiration at this stage yields pus, confirming the diagnosis.[1][40][8] If untreated, progression to the late or disseminated stage (stage 3) occurs, characterized by abscess rupture, systemic toxemia, and potential metastatic infections such as osteomyelitis or septicemia. This phase features intense pain, high fever, shock, and widespread muscle damage with multi-organ involvement due to bacteremia; delayed diagnosis and inadequate intervention are key factors prolonging the transition through earlier stages, with the total untreated course averaging 2 to 4 weeks.[40][8][1]Clinical features

Symptoms and signs

Pyomyositis typically presents with severe localized muscle pain that intensifies with movement or palpation, often accompanied by swelling, warmth, and erythema over the affected area. In children, patients may exhibit a limp or refusal to bear weight on the involved limb. These local manifestations arise due to inflammation and suppuration within the skeletal muscle.[7][3][42] Systemic signs are common and include fever in 70-90% of cases, often accompanied by chills and malaise. Laboratory findings frequently reveal leukocytosis with neutrophilia, as well as elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). These indicators reflect the ongoing bacterial infection and inflammatory response.[7][3][43] The condition progresses through distinct stages, beginning with an early invasive phase characterized by cramping or dull muscle pain that evolves into a more intense throbbing ache, along with low-grade fever and localized edema but minimal tenderness. In the suppurative stage, symptoms worsen with high fever, marked tenderness, and swelling, potentially forming a fluctuant abscess palpable as a mass. If untreated, it may advance to late-stage sepsis with severe systemic toxicity. Atypical presentations can include minimal local signs when deep muscles such as the iliopsoas are involved, and polyfocal involvement occurs in 10-20% of cases, particularly among immunocompromised patients. Pyomyositis commonly affects the lower limbs.[7][42][17][44]Common sites of involvement

Pyomyositis most commonly involves muscles of the lower extremities and pelvis, with quadriceps, gluteal, and iliopsoas frequently affected, though the relative frequencies vary by geographic region and population. For instance, in some North Indian cohorts, iliopsoas involvement reaches 46%, gluteal 36%, and thigh muscles 28%.[45][14] The hamstrings contribute to lower limb cases, often presenting with localized pain and swelling that limits mobility.[14] Involvement of the trunk and pelvic muscles is common, occurring in 20-50% of cases depending on the study, encompassing deep and often occult sites such as the iliopsoas, abdominal wall muscles, and paraspinal groups, which can complicate early detection due to nonspecific symptoms like back or abdominal discomfort.[45][26] These axial structures are particularly prevalent in pediatric cases, where pelvic girdle muscles like the iliopsoas and obturator internus predominate.[46] Upper extremity involvement is less common, comprising approximately 10-15% of cases, typically affecting the deltoid or biceps brachii muscles, though this pattern increases among intravenous drug users due to hematogenous seeding from injection sites.[46][47] In adults, limb girdle and proximal lower limb muscles are more routinely implicated compared to the axial predominance seen in infants.[48][26] Most infections are unifocal, affecting a single muscle group in about 80% of patients, but multifocal disease—spanning multiple sites—arises more frequently in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV, where up to 40% may exhibit disseminated involvement.[49][26]Diagnosis

Clinical evaluation

Clinical evaluation of pyomyositis begins with a detailed patient history to identify potential risk factors and symptom progression that raise suspicion for this condition. Key historical elements include recent trauma or strenuous physical activity; in case series, 20 to 60 percent of individuals with primary pyomyositis report prior vigorous exercise or trauma, particularly in otherwise healthy individuals.[50] Patients often report a subacute onset of localized muscle pain initially resembling a strain or contusion, progressing over 1 to 3 weeks to more intense discomfort accompanied by low-grade fever and malaise.[40] Inquiry should also cover duration of fever, which is typically present but intermittent in early stages, as well as recent travel to tropical regions where pyomyositis is more prevalent, though cases occur worldwide.[51] Immunosuppression from conditions like diabetes, HIV, or chemotherapy is a critical risk factor to elicit, as it predisposes to hematogenous spread of bacteria to skeletal muscle.[50] On physical examination, focal tenderness over the affected muscle is a hallmark finding, often with localized swelling and induration that limits range of motion due to pain.[52] Commonly involved sites such as the quadriceps, gluteus, or iliopsoas may exhibit warmth and erythema, though skin changes can be subtle or absent, distinguishing it from superficial infections.[40] Systemic signs, including tachycardia and low-grade fever, may indicate early bacteremia, while vital sign instability such as hypotension signals potential sepsis.[51] In children or immunocompromised patients, examination may reveal more diffuse involvement or nonspecific limb pain without obvious swelling.[7] Red flags warranting urgent evaluation include rapid symptom worsening over days, multifocal muscle involvement suggesting disseminated infection, or indicators of sepsis such as hypotension, altered mental status, or severe tachycardia.[40] These features heighten suspicion in patients with relevant travel or immunosuppression history, prompting consideration of pyomyositis over benign musculoskeletal complaints.[50] Differential diagnosis during initial assessment often includes conditions that mimic pyomyositis's early presentation, such as cellulitis with overlying skin involvement or muscle strain without systemic features.[52] Osteomyelitis may present similarly with deep bone-adjacent pain and limited motion, while rheumatic fever can cause migratory arthralgias and fever in pediatric cases, necessitating careful history to differentiate based on progression and risk factors.[7] Typical symptoms like localized pain and swelling, along with risk factors such as trauma, further guide suspicion toward pyomyositis in the appropriate clinical context.[51]Laboratory investigations

Laboratory investigations play a crucial role in supporting the diagnosis of pyomyositis and assessing disease severity, though findings are often nonspecific and overlap with other infectious processes. Patients typically present with leukocytosis, with white blood cell (WBC) counts ranging from 10,000 to 20,000/μL and a predominance of neutrophils reflecting the acute inflammatory response.[2] C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are markedly elevated, often exceeding 100 mg/L, while erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is commonly greater than 50 mm/hr, both serving as sensitive indicators of ongoing inflammation.[53] These markers tend to rise progressively through the disease stages and correlate with clinical severity, aiding in monitoring response to therapy.[14] Blood cultures are recommended in all suspected cases to identify the pathogen and guide antibiotic selection, though positivity rates are low at 5-35%, attributed to transient bacteremia in early stages.[54] Yield is higher in stage 3 pyomyositis, where dissemination increases the likelihood of detecting organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus in up to 46% of staphylococcal cases.[2] Negative results do not rule out the diagnosis but underscore the need for tissue sampling. Additional laboratory findings may include mild anemia, often normocytic and related to chronic inflammation or infection, as well as elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels in instances of associated myonecrosis.[55] In patients with risk factors such as immunosuppression or residence in endemic areas, testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is advisable due to its association with increased susceptibility to pyomyositis.[42] The definitive microbiologic confirmation comes from aspiration of the affected muscle, where Gram stain and culture of the purulent material establish the etiology, most frequently identifying S. aureus as the causative agent.[53] This procedure not only confirms the diagnosis but also provides susceptibility data essential for targeted therapy, with pus cultures yielding positive results in the majority of cases when performed prior to antibiotics.[2]Imaging studies

Imaging studies play a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of pyomyositis by visualizing muscle inflammation, abscess formation, and associated complications, particularly in the suppurative stage where localized pus collections predominate.[56] These modalities help differentiate pyomyositis from mimics such as cellulitis or osteomyelitis, guiding therapeutic decisions like drainage.[57] Ultrasound serves as the first-line imaging tool, especially for superficial muscle involvement, due to its accessibility, lack of radiation, and ability to guide percutaneous aspiration.[58] It detects hypoechoic fluid collections within enlarged muscles, with surrounding hyperemia indicating active infection, and demonstrates high sensitivity (up to 96.7%) for soft-tissue abscesses compared to CT (76.7%).[59] However, its efficacy is limited for deep-seated lesions owing to operator dependence and acoustic shadowing from overlying structures.[56] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing pyomyositis, particularly in deep or axial muscles, offering superior soft-tissue contrast without ionizing radiation.[56] In the phlegmonous stage, MRI reveals muscle enlargement with T2 hyperintensity and loss of normal fascial planes due to edema; in the suppurative stage, it shows well-defined abscesses as T1 isointense/hypointense central collections with hyperintense T2 rims and peripheral gadolinium enhancement.[57] Sensitivity reaches 97% for detecting soft-tissue abscesses, aiding in assessing extent and complications like bone involvement.[56] Limitations include potential overestimation of disease from reactive edema and contraindications in patients with non-MRI-compatible implants.[58] Computed tomography (CT) provides a valuable alternative, especially for iliopsoas or pelvic pyomyositis, where it identifies muscle enlargement, heterogeneous low-attenuation areas, central fluid collections with rim enhancement, and complications like gas or necrosis.[57] It is particularly useful in emergency settings for rapid evaluation but is less sensitive in early stages and involves radiation exposure, raising concerns in pediatric patients.[56] Plain radiographs (X-rays) are nonspecific and rarely diagnostic, typically showing only soft-tissue swelling, muscle enlargement, or obliteration of fat planes, without delineating abscesses.[58] Nuclear medicine scans, such as gallium-67 scintigraphy, can localize multifocal inflammation but are infrequently used due to their nonspecificity, high cost, and longer acquisition times compared to MRI or CT.[58]Treatment

Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy is the cornerstone of pyomyositis management, targeting the predominant pathogen Staphylococcus aureus, which accounts for the majority of cases.[2] Empiric treatment typically begins with intravenous anti-staphylococcal agents to cover both methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), especially in regions with high MRSA prevalence. For MSSA-suspected cases, an anti-staphylococcal beta-lactam such as nafcillin or oxacillin is recommended at 150-200 mg/kg/day divided every 4-6 hours in pediatric patients or 2 g every 4-6 hours in adults.[8][35] If MRSA is suspected, vancomycin is the first-line option at 15-20 mg/kg every 8-12 hours, adjusted to achieve trough levels of 15-20 mcg/mL.[35][60] Therapy is de-escalated based on culture and sensitivity results from blood or abscess aspirates, narrowing to pathogen-specific agents such as cefazolin (50-100 mg/kg/day IV divided every 8 hours for MSSA) or alternatives like daptomycin (4-6 mg/kg IV daily) for MRSA if vancomycin-intolerant.[60][35] In immunocompromised patients or those with recent trauma, empiric coverage may include an agent active against gram-negative bacilli, such as piperacillin-tazobactam.[60] The total duration is generally 3-4 weeks, starting with 1-2 weeks of intravenous therapy until clinical improvement (e.g., defervescence and reduced inflammatory markers), followed by 2-4 weeks of oral step-down therapy such as clindamycin (30-40 mg/kg/day divided every 6-8 hours in children or 300-450 mg every 6-8 hours in adults) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX; 8-10 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim component divided every 12 hours) for susceptible strains.[8][3] In severe S. aureus cases, particularly those with systemic toxicity, adjunctive clindamycin is often added to suppress exotoxin production by inhibiting protein synthesis, even if the isolate is sensitive to beta-lactams.[61][35] This combination enhances outcomes in toxin-mediated infections, though its routine use remains under evaluation in ongoing trials.[61] Response to therapy is monitored through serial laboratory assessments, including white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, with de-escalation or extension guided by clinical progress and repeat cultures if bacteremia persists.[60][2]Surgical management

Surgical management plays a critical role in treating pyomyositis during the suppurative phase, when intramuscular abscesses form and fail to resolve with antibiotics alone. Indications for intervention include the presence of drainable abscess collections, particularly those associated with lack of clinical improvement after 48-72 hours of appropriate antibiotic therapy or accompanied by systemic sepsis.[62] Percutaneous drainage, guided by ultrasound or computed tomography, is the preferred initial approach for smaller or deeply located abscesses, allowing minimally invasive aspiration and potential catheter placement for ongoing drainage. For larger, multiloculated, or superficial abscesses, open incision and drainage provides more comprehensive access to ensure complete pus evacuation.[2][63] Key techniques involve careful incision along the muscle axis to avoid neurovascular structures, followed by finger exploration to disrupt loculations, thorough debridement of necrotic material, and copious irrigation of the cavity with 0.9% saline solution. A drain is typically placed and secured, to be removed after several days once output diminishes. In approximately 28% of cases, multiple procedures are necessary to achieve source control.[2][63] Following surgery, intravenous antibiotics are continued, guided by culture sensitivities, for a median duration of about 18 days or until clinical resolution, with serial imaging to monitor for residual infection or recurrence.[2][62]Prognosis and complications

Prognosis

With prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment, the overall mortality rate for pyomyositis is low, ranging from 1% to 4% in non-endemic settings with access to advanced care.[64] However, delayed intervention or progression to late-stage disease (stage 3 with systemic involvement) can elevate mortality to up to 23%.[30] In a single-center retrospective analysis of 61 cases, the mortality rate was 5%, with all deaths occurring in treatment failures involving disseminated infections.[2] Recovery rates are high with early intervention, achieving 84-95% full resolution without recurrent infection or need for prolonged therapy.[2] Average hospitalization duration is 7-14 days, followed by 3-6 weeks of antibiotics for complete recovery.[3] A literature review of over 200 cases emphasized that pre-suppurative stage treatment often leads to rapid resolution without surgery.[65] Key factors influencing outcomes include timing of diagnosis and underlying conditions; early detection significantly improves survival and reduces complications.[66] Comorbidities such as HIV infection or diabetes mellitus worsen prognosis due to increased risk of dissemination and treatment resistance.[30] In contrast, outcomes are excellent in children, who often achieve full recovery without long-term sequelae when treated promptly.[8] Long-term effects are uncommon, with rare instances of chronic pain or muscle weakness reported in fewer than 5% of cases post-resolution.[2] Recent trends as of 2023 indicate rising community-acquired MRSA cases in temperate regions, potentially impacting prognosis through increased treatment challenges.[2]Complications

Local complications of pyomyositis primarily arise from inadequate or delayed management of intramuscular abscesses and may include abscess rupture leading to extension into adjacent tissues, formation of chronic sinus tracts, and muscle fibrosis or contracture causing functional impairment.[42] Systemic complications are more severe and often stem from dissemination in late-stage disease. Bacteremia and sepsis occur frequently if the infection progresses untreated, with blood cultures positive in 10-50% of cases.[45] Metastatic infections, including osteomyelitis (reported in 5% to 73% across studies) and septic arthritis (2% to 16%), complicate approximately 10% of cases through hematogenous spread.[30] Rare but life-threatening complications include multiorgan failure, toxic shock syndrome (documented in isolated cases with Staphylococcus aureus), and renal impairment due to dehydration or sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. These risks are elevated in multifocal pyomyositis or infections involving Gram-negative bacteria, which are less common but associated with immunosuppression and poorer outcomes. Early surgical drainage substantially mitigates the likelihood of both local and systemic complications.[42][30][67]References

- https://wikimsk.org/wiki/Pyomyositis