Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

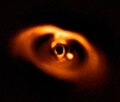

Circumplanetary disk

View on Wikipedia

A circumplanetary disk (or circumplanetary disc, short CPD) is a torus, pancake or ring-shaped accumulation of matter composed of gas, dust, planetesimals, asteroids or collision fragments in orbit around a planet. They are reservoirs of material out of which moons (or exomoons or subsatellites) may form.[2] Such a disk can manifest itself in various ways.

In August 2018, astronomers reported the probable detection of a circumplanetary disk around CS Cha B.[3] The authors state that "The CS Cha system is the only system in which a circumplanetary disc is likely present as well as a resolved circumstellar disc."[4] In 2020 though, the parameters of CS Cha B were revised, making it an accreting red dwarf star, and making the disk circumstellar.[5]

Theory

[edit]

A giant planet will mainly form via core accretion. In this scenario a core forms via the accretion of small solids. Once the core is massive enough it might carve a gap onto the circumstellar disk around the host star. Material will flow from the edges of the circumstellar disk towards the planet in streams and around the planet it will form a circumplanetary disk. A circumplanetary disk does therefore form during the late stage of giant planet formation.[7][8] The size of the disk is limited by the Hill radius. A circumplanetary disk will have a maximal disk size of 0.4 times the Hill radius.[9][10] The disk also has a "dead zone" at the mid-plane that is non-turbulent and a turbulent disk surface. The dead zone is a favourable region for satellites (exomoons) to form.[11] The circumplanetary disk will go through different stages of evolution. A classification similar to young stellar objects was proposed. In the early stage the circumplanetary disk will be full. Newly forming satellites will carve a gap close to the planet, turning the disk into a "transitional" disk. In the last stage the disk is full, but has a low density and can be classified as "evolved".[6] Additional to a circumplanetary disk, a protoplanet can also drive an outflow.[12][13] One such outflow is identified via shocked SiS for HD 169142b.[14]

Circumplanetary disks are consistent with the formation of the Galilean satellites. The older models at the time were not consistent with the icy composition of the moons and the incomplete differentiation of Callisto. A circumplanetary disk with an inflow of 2*10−7 MJ/year of gas and solids was consistent with the conditions needed to form the moons, including the low temperature during the late stage of the formation of Jupiter.[15] But later simulations found the circumplanetary disk too hot for the satellites to form and survive.[16][10] This was later solved by introducing the dead zone within circumplanetary disks which is a favourable region for satellite formation and explains the compact orbit of Galilean satellites.[11]

Candidates around other exoplanets

[edit]Possible circumplanetary disks have also been detected around exoplanets, HD 100546 b,[17] AS 209 b[18] and HD 169142 b[19] or planetary-mass companions (PMC; 10-20 MJ, separation ≥100 AU), such as GSC 06214-00210 b[20] and DH Tauri b.[21]

A disk was detected in sub-mm with ALMA around SR 12 c, a planetary-mass companion. SR 12 c might not have formed from the circumstellar disk material of the host star SR 12, so it might not be considered a true circumplanetary disk. PMC disks are relative common around young objects and are easier to study when compared to circumplanetary disks.[22] The protoplanet Delorme 1 (AB)b shows strong evidence of accretion from a circumplanetary disk, but the disk is as of now (September 2024) not detected in the infrared.[23] A disk was detected around the planet YSES 1b with the James Webb Space Telescope. The disk shows emission by small hot olivine grains. This is seen as evidence for collisions between satellites forming inside the disk.[24]

Several disks were detected around nearby isolated planetary-mass objects. Disks around such objects within 300 parsecs were found in Rho Ophiuchi Complex,[25] Taurus Complex (e.g. KPNO-Tau 12),[25][26] Lupus I Cloud[27] and the Chamaeleon Complex (e.g. the well studied OTS 44 and Cha 110913−773444[28]). One remarkable close free-floating disk-bearing object is 2MASS J11151597+1937266, which is only 45 parsec distant. It could be a planetary-mass object or a low-mass brown dwarf.[29] These objects with disks are free-floating and are most of the time called circumstellar disks, despite likely being similar to circumplanetary disks.

2M1207b was suspected to have a circumplanetary disk in the past.[30] New observations from JWST/NIRSpec were able to confirm accretion from an unseen disk by detecting emission from hydrogen and helium. The classification of a circumplanetary disk is however being disputed because 2M1207b (or 2M1207B) might be classified as a binary together with 2M1207A and not an exoplanet. This would make the disk around 2M1207b a circumstellar disk, despite not being around a star, but around a 5-6 MJup planetary-mass object.[31]

PDS 70

[edit]The disk around the planet c of the PDS 70 system is the best evidence for a circumplanetary disk at the time of its discovery. The exoplanet is part of the multiplanetary PDS 70 star system, about 370 light-years (110 parsecs) from Earth.[32]

PDS 70b

[edit]In June 2019 astronomers reported the detection of evidence of a circumplanetary disk around PDS 70b[33] using spectroscopy and accretion signatures. Both types of these signatures had previously been detected for other planetary candidates. A later infrared characterization could not confirm the spectroscopic evidence for the disk around PDS 70b and reports weak evidence that the current data favors a model with a single blackbody component.[34] Interferometric observations with the James Webb Space Telescope's Fine Guidance Sensor and Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph and archived data found tentative evidence that PDS 70b has a circumplanetary disk.[35]

PDS 70c

[edit]In July 2019 astronomers reported the first-ever detection using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA)[36][37][38] of a circumplanetary disk.[36][37][39] ALMA studies, using millimetre and submillimetre wavelengths, are better at observing dust concentrated in interplanetary regions, since stars emit comparatively little light at these wavelengths, and since optical observations are often obscured by overwhelming glare from the bright host star. The circumplanetary disk was detected around a young massive, Jupiter-like exoplanet, PDS 70c.[36][37][39]

According to Andrea Isella, lead researcher from the Rice University in Houston, Texas, "For the first time, we can conclusively see the tell-tale signs of a circumplanetary disk, which helps to support many of the current theories of planet formation ... By comparing our observations to the high-resolution infrared and optical images, we can clearly see that an otherwise enigmatic concentration of tiny dust particles is actually a planet-girding disk of dust, the first such feature ever conclusively observed."[38] Jason Wang from Caltech, lead researcher of another publication, describes, "if a planet appears to sit on top of the disk, which is the case with PDS 70c"[40] then the signal around PDS 70c needs to be spatially separated from the outer ring, not the case in 2019. However, in July 2021 higher resolution, conclusively resolved data were presented.[41]

The planet PDS 70c is detected in H-alpha, which is seen as evidence that it accretes material from the circumplanetary disk at a rate of 10−8±0.4 MJ per year.[42] From ALMA observations it was shown that this disk has a radius smaller than 1.2 astronomical units (AU) or a third of the Hill radius. The dust mass was estimated around 0.007 or 0.031 M🜨 (0.57 to 2.5 Moon masses), depending on the grain size used for the modelling.[41] Later modelling showed that the disk around PDS 70c is optically thick and has an estimated dust mass of 0.07 to 0.7 M🜨 (5.7 to 57 Moon masses). The total (dust+gas) mass of the disk should be higher. The planet's luminosity is the dominant heating mechanism within 0.6 AU of the CPD. Beyond that the photons from the star heat the disk.[43] Observations with JWST NIRCam showed a large spiral-like feature near PDS 70c. This feature is only seen after the disk around PDS 70 was removed. Part of this spiral-like feature was interpreted as an accretion stream that feeds the circumplanetary disk around PDS 70c.[44]

See also

[edit]- Accretion disc – Structure formed by diffuse material in orbital motion around a massive central body

- Circumstellar envelope – Part of a star

- Disrupted planet – Planetary object disrupted by other body

- Extrasolar planet – Planet outside of the Solar System

- Formation and evolution of the Solar System

- Protoplanetary disk – Gas and dust surrounding a newly formed star

- Ring system – Ring of cosmic dust orbiting an astronomical object

References

[edit]- ^ Blue, Charles (11 July 2019). "'Moon-forming' Circumplanetary Disk Discovered in Distant Star System". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Parks, Jake (8 November 2021). "Snapshot: ALMA spots moon-forming disk around distant exoplanet - This stellar shot serves as the first unambiguous detection of a circumplanetary disk capable of brewing its own moon". Astronomy. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Ginski, Christian (August 2018). "First direct detection of a polarized companion outside a resolved circumbinary disk around CS Chamaeleonis". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616 (79): 18. arXiv:1805.02261. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A..79G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201732417.

- ^ Starr, Michelle. "Astronomers Have Accidentally Taken a Direct Photo of a Possible Baby Exoplanet". Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Haffert, S. Y.; Van Holstein, R. G.; Ginski, C.; Brinchmann, J.; Snellen, I. A. G.; Milli, J.; Stolker, T.; Keller, C. U.; Girard, J. (2020), "CS Cha B: A disc-obscured M-type star mimicking a polarised planetary companion", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 640: L12, arXiv:2007.07831, Bibcode:2020A&A...640L..12H, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202038706, S2CID 220525346

- ^ a b Sun, Xilei; Huang, Pinghui; Dong, Ruobing; Liu, Shang-Fei (1 September 2024). "Observational Characteristics of Circumplanetary-mass-object Disks in the Era of James Webb Space Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal. 972 (1): 25. arXiv:2406.09501. Bibcode:2024ApJ...972...25S. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad57c2. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ D'Angelo, G.; Lissauer, J. J. (2018). "Formation of Giant Planets". In Deeg H., Belmonte J. (ed.). Handbook of Exoplanets. Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature. pp. 2319–2343. arXiv:1806.05649. Bibcode:2018haex.bookE.140D. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55333-7_140. ISBN 978-3-319-55332-0. S2CID 116913980.

- ^ Lubow, S. H.; Seibert, M.; Artymowicz, P. (1 December 1999). "Disk Accretion onto High-Mass Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 526 (2): 1001–1012. arXiv:astro-ph/9910404. Bibcode:1999ApJ...526.1001L. doi:10.1086/308045. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Martin, R. G.; Lubow, S. H. (1 October 2011). "The Gravo-magneto Limit Cycle in Accretion Disks". The Astrophysical Journal. 740 (1): L6. arXiv:1108.4960. Bibcode:2011ApJ...740L...6M. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/740/1/L6. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ a b Chen, Cheng; Yang, Chao-Chin; Martin, Rebecca G.; Zhu, Zhaohuan (1 January 2021). "The evolution of a circumplanetary disc with a dead zone". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 500 (3): 2822–2830. arXiv:2011.01384. Bibcode:2021MNRAS.500.2822C. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa3427. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b Lubow, Stephen H.; Martin, Rebecca G. (1 January 2013). "Dead zones in circumplanetary discs as formation sites for regular satellites". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 428 (3): 2668–2673. arXiv:1210.4579. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.428.2668L. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts229. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Quillen, A. C.; Trilling, D. E. (1 December 1998). "Do Proto-jovian Planets Drive Outflows?". The Astrophysical Journal. 508 (2): 707–713. arXiv:astro-ph/9712033. Bibcode:1998ApJ...508..707Q. doi:10.1086/306421. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Fendt, Ch. (1 December 2003). "Magnetically driven outflows from Jovian circum-planetary accretion disks". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 411 (3): 623–635. arXiv:astro-ph/0310021. Bibcode:2003A&A...411..623F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20034154. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Law, Charles J.; Booth, Alice S.; Öberg, Karin I. (1 June 2023). "SO and SiS Emission Tracing an Embedded Planet and Compact 12CO and 13CO Counterparts in the HD 169142 Disk". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 952 (1): L19. arXiv:2306.13710. Bibcode:2023ApJ...952L..19L. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/acdfd0.

- ^ Canup, Robin M.; Ward, William R. (1 December 2002). "Formation of the Galilean Satellites: Conditions of Accretion". The Astronomical Journal. 124 (6): 3404–3423. Bibcode:2002AJ....124.3404C. doi:10.1086/344684. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ Estrada, P. R.; Mosqueira, I.; Lissauer, J. J.; D'Angelo, G.; Cruikshank, D. P. (1 January 2009). Formation of Jupiter and Conditions for Accretion of the Galilean Satellites. Bibcode:2009euro.book...27E.

- ^ Quanz, Sascha P.; et al. (July 2015). "Confirmation and Characterization of the Protoplanet HD 100546 b—Direct Evidence for Gas Giant Planet Formation at 50 AU". The Astrophysical Journal. 807 (1): 64. arXiv:1412.5173. Bibcode:2015ApJ...807...64Q. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/807/1/64. S2CID 119119314.

- ^ Bae, Jaehan; et al. (August 2022). "Molecules with ALMA at Planet-forming Scales (MAPS): A Circumplanetary Disk Candidate in Molecular-line Emission in the AS 209 Disk". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 934 (2): 20. arXiv:2207.05923. Bibcode:2022ApJ...934L..20B. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac7fa3. S2CID 250492936.

- ^ Hammond, Iain; Christiaens, Valentin; Price, Daniel J.; Toci, Claudia; Pinte, Christophe; Juillard, Sandrine; Garg, Himanshi (23 February 2023). "Confirmation and Keplerian motion of the gap-carving protoplanet HD 169142 B". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 522: L51 – L55. arXiv:2302.11302. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slad027.

- ^ Bowler, Brendan P.; et al. (June 2015). "An ALMA Constraint on the GSC 6214-210 B Circum-Substellar Accretion Disk Mass". The Astrophysical Journal. 805 (2): L17. arXiv:1505.01483. Bibcode:2015ApJ...805L..17B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/805/2/L17. S2CID 29008641.

- ^ Wolff, Schuyler G.; et al. (July 2017). "An Upper Limit on the Mass of the Circumplanetary Disk for DH Tau b". The Astronomical Journal. 154 (1): 26. arXiv:1705.08470. Bibcode:2017AJ....154...26W. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa74cd. S2CID 119339454.

- ^ Wu, Ya-Lin; Bowler, Brendan P.; Sheehan, Patrick D.; Close, Laird M.; Eisner, Joshua A.; Best, William M. J.; Ward-Duong, Kimberly; Zhu, Zhaohuan; Kraus, Adam L. (1 May 2022). "ALMA Discovery of a Disk around the Planetary-mass Companion SR 12 c". The Astrophysical Journal. 930 (1): L3. arXiv:2204.06013. Bibcode:2022ApJ...930L...3W. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac6420. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Ringqvist, Simon C.; Viswanath, Gayathri; Aoyama, Yuhiko; Janson, Markus; Marleau, Gabriel-Dominique; Brandeker, Alexis (1 January 2023). "Resolved near-UV hydrogen emission lines at 40-Myr super-Jovian protoplanet Delorme 1 (AB)b. Indications of magnetospheric accretion". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 669: L12. arXiv:2212.03207. Bibcode:2023A&A...669L..12R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202245424. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Hoch, K. K. W.; Rowland, M.; Petrus, S.; Nasedkin, E.; Ingebretsen, C.; Kammerer, J.; Perrin, M.; d'Orazi, V.; Balmer, W. O.; Barman, T.; Bonnefoy, M.; Chauvin, G.; Chen, C.; De Rosa, R. J.; Girard, J.; Gonzales, E.; Kenworthy, M.; Konopacky, Q. M.; MacIntosh, B.; Moran, S. E.; Morley, C. V.; Palma-Bifani, P.; Pueyo, L.; Ren, B.; Rickman, E.; Ruffio, J.-B.; Theissen, C. A.; Ward-Duong, K.; Zhang, Y. (2025). "Silicate clouds and a circumplanetary disk in the YSES-1 exoplanet system". Nature. 643 (8073): 938–942. arXiv:2507.18861. Bibcode:2025Natur.643..938H. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09174-w. PMID 40494394.

- ^ a b Rilinger, Anneliese M.; Espaillat, Catherine C. (1 November 2021). "Disk Masses and Dust Evolution of Protoplanetary Disks around Brown Dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal. 921 (2): 182. arXiv:2106.05247. Bibcode:2021ApJ...921..182R. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac09e5. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Best, William M. J.; Liu, Michael C.; Magnier, Eugene A.; Bowler, Brendan P.; Aller, Kimberly M.; Zhang, Zhoujian; Kotson, Michael C.; Burgett, W. S.; Chambers, K. C.; Draper, P. W.; Flewelling, H.; Hodapp, K. W.; Kaiser, N.; Metcalfe, N.; Wainscoat, R. J. (1 March 2017). "A Search for L/T Transition Dwarfs with Pan-STARRS1 and WISE. III. Young L Dwarf Discoveries and Proper Motion Catalogs in Taurus and Scorpius-Centaurus". The Astrophysical Journal. 837 (1): 95. arXiv:1702.00789. Bibcode:2017ApJ...837...95B. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa5df0. hdl:1721.1/109753. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Jayawardhana, Ray; Ivanov, Valentin D. (1 August 2006). "Spectroscopy of Young Planetary Mass Candidates with Disks". The Astrophysical Journal. 647 (2): L167 – L170. arXiv:astro-ph/0607152. Bibcode:2006ApJ...647L.167J. doi:10.1086/507522. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Luhman, K. L.; et al. (December 2005). "Discovery of a Planetary-Mass Brown Dwarf with a Circumstellar Disk". The Astrophysical Journal. 635 (1): L93 – L96. arXiv:astro-ph/0511807. Bibcode:2005ApJ...635L..93L. doi:10.1086/498868. S2CID 11685964.

- ^ Theissen, Christopher A.; Burgasser, Adam J.; Bardalez Gagliuffi, Daniella C.; Hardegree-Ullman, Kevin K.; Gagné, Jonathan; Schmidt, Sarah J.; West, Andrew A. (1 January 2018). "2MASS J11151597+1937266: A Young, Dusty, Isolated, Planetary-mass Object with a Potential Wide Stellar Companion". The Astrophysical Journal. 853 (1): 75. arXiv:1712.03964. Bibcode:2018ApJ...853...75T. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaa0cf. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Mohanty, Subhanjoy; et al. (March 2007). "The Planetary Mass Companion 2MASS 1207-3932B: Temperature, Mass, and Evidence for an Edge-on Disk". The Astrophysical Journal. 657 (2): 1064–1091. arXiv:astro-ph/0610550. Bibcode:2007ApJ...657.1064M. doi:10.1086/510877. S2CID 17326111.

- ^ Luhman, K. L.; Tremblin, P.; Birkmann, S. M.; Manjavacas, E.; Valenti, J.; Alves de Oliveira, C.; Beck, T. L.; Giardino, G.; Lützgendorf, N.; Rauscher, B. J.; Sirianni, M. (1 June 2023). "JWST/NIRSpec Observations of the Planetary Mass Companion TWA 27B". The Astrophysical Journal. 949 (2): L36. arXiv:2305.18603. Bibcode:2023ApJ...949L..36L. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/acd635. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (12 July 2019). "Astronomers Think They've Spotted a Moon Forming Around an Exoplanet". Gizmodo. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ Christiaens, Valentin (June 2019). "Evidence for a circumplanetary disk around protoplanet PDS 70 b". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 877 (2): L33. arXiv:1905.06370. Bibcode:2019ApJ...877L..33C. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab212b. S2CID 155100321.

- ^ Stolker, T.; Marleau, G.-D.; Cugno, G.; Mollière, P.; Quanz, S. P.; Todorov, K. O.; Kühn, J. (December 2020). "MIRACLES: atmospheric characterization of directly imaged planets and substellar companions at 4–5 μ m: II. Constraints on the mass and radius of the enshrouded planet PDS 70 b". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 644: A13. arXiv:2009.04483. Bibcode:2020A&A...644A..13S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202038878. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Blakely, Dori; Johnstone, Doug; Cugno, Gabriele; Sivaramakrishnan, Anand; Tuthill, Peter; Dong, Ruobing; Pope, Benjamin J. S.; Albert, Loïc; Charles, Max (2024). "The James Webb Interferometer: Space-based interferometric detections of PDS 70 b and c at 4.8 μm". The Astronomical Journal. 169 (3): 137. arXiv:2404.13032. Bibcode:2025AJ....169..137B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ad9b94.

- ^ a b c Isella, Andrea; et al. (11 July 2019). "Detection of Continuum Submillimeter Emission Associated with Candidate Protoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 879 (2): L25. arXiv:1906.06308. Bibcode:2019ApJ...879L..25I. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab2a12. S2CID 189897829.

- ^ a b c Blue, Charles E. (11 July 2019). "'Moon-forming' Circumplanetary Disk Discovered in Distant Star System". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ a b Carne, Nick (13 July 2019). "'Moon-forming' disk found in distant star system - Discovery helps confirm theories of planet formation, astronomers say". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ a b Boyd, Jade (11 July 2019). "Moon-forming disk discovered around distant planet". Phys.org. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Observatory, W. M. Keck. "Astronomers confirm existence of two giant newborn planets in PDS 70 system". phys.org. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ a b Benisty, Myriam; Bae, Jaehan; Facchini, Stefano; Keppler, Miriam; Teague, Richard; Isella, Andrea; Kurtovic, Nicolas T.; Pérez, Laura M.; Sierra, Anibal; Andrews, Sean M.; Carpenter, John (1 July 2021). "A Circumplanetary Disk around PDS70c". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 916 (1): L2. arXiv:2108.07123. Bibcode:2021ApJ...916L...2B. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac0f83. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 236186222.

- ^ Haffert, S. Y.; Bohn, A. J.; de Boer, J.; Snellen, I. A. G.; Brinchmann, J.; Girard, J. H.; Keller, C. U.; Bacon, R. (1 June 2019). "Two accreting protoplanets around the young star PDS 70". Nature Astronomy. 3 (8): 749–754. arXiv:1906.01486. Bibcode:2019NatAs...3..749H. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0780-5. hdl:1887/83158. ISSN 2397-3366.

- ^ Portilla-Revelo, B.; Kamp, I.; Rab, Ch.; van Dishoeck, E. F.; Keppler, M.; Min, M.; Muro-Arena, G. A. (1 February 2022). "Self-consistent modelling of the dust component in protoplanetary and circumplanetary disks: the case of PDS 70". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 658: A89. arXiv:2111.08648. Bibcode:2022A&A...658A..89P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202141764. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Christiaens, V.; Samland, M.; Henning, Th.; Portilla-Revelo, B.; Perotti, G.; Matthews, E.; Absil, O.; Decin, L.; Kamp, I.; Boccaletti, A.; Tabone, B.; Marleau, G. -D.; van Dishoeck, E. F.; Güdel, M.; Lagage, P. -O. (1 May 2024). "MINDS: JWST/NIRCam imaging of the protoplanetary disk PDS 70. A spiral accretion stream and a potential third protoplanet". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 685: L1. arXiv:2403.04855. Bibcode:2024A&A...685L...1C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202349089. hdl:20.500.11850/673047. ISSN 0004-6361.