Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Outer space

View on Wikipedia

Outer space, or simply space, is the expanse that exists beyond Earth's atmosphere and between celestial bodies.[1] It contains ultra-low levels of particle densities, constituting a near-perfect vacuum[2] of predominantly hydrogen and helium plasma, permeated by electromagnetic radiation, cosmic rays, neutrinos, magnetic fields and dust. The baseline temperature of outer space, as set by the background radiation from the Big Bang, is 2.7 kelvins (−270 °C; −455 °F).[3]

The plasma between galaxies is thought to account for about half of the baryonic (ordinary) matter in the universe, having a number density of less than one hydrogen atom per cubic metre and a kinetic temperature of millions of kelvins.[4] Local concentrations of matter have condensed into stars and galaxies. Intergalactic space takes up most of the volume of the universe, but even galaxies and star systems consist almost entirely of empty space. Most of the remaining mass-energy in the observable universe is made up of an unknown form, dubbed dark matter and dark energy.[5][6][7]

Outer space does not begin at a definite altitude above Earth's surface. The Kármán line, an altitude of 100 km (62 mi) above sea level,[8][9] is conventionally used as the start of outer space in space treaties and for aerospace records keeping. Certain portions of the upper stratosphere and the mesosphere are sometimes referred to as "near space". The framework for international space law was established by the Outer Space Treaty, which entered into force on 10 October 1967. This treaty precludes any claims of national sovereignty and permits all states to freely explore outer space. Despite the drafting of UN resolutions for the peaceful uses of outer space, anti-satellite weapons have been tested in Earth orbit.

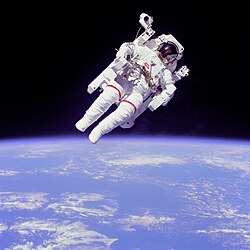

The concept that the space between the Earth and the Moon must be a vacuum was first proposed in the 17th century after scientists discovered that air pressure decreased with altitude. The immense scale of outer space was grasped in the 20th century when the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy was first measured. Humans began the physical exploration of space later in the same century with the advent of high-altitude balloon flights. This was followed by crewed rocket flights and, then, crewed Earth orbit, first achieved by Yuri Gagarin of the Soviet Union in 1961. The economic cost of putting objects, including humans, into space is very high, limiting human spaceflight to low Earth orbit and the Moon. On the other hand, uncrewed spacecraft have reached all of the known planets in the Solar System. Outer space represents a challenging environment for human exploration because of the hazards of vacuum and radiation. Microgravity has a negative effect on human physiology that causes both muscle atrophy and bone loss.

Terminology

[edit]The use of the short version space, as meaning "the region beyond Earth's sky", predates the use of full term "outer space", with the earliest recorded use of this meaning in an epic poem by John Milton called Paradise Lost, published in 1667.[10][11]

The term outward space existed in a poem from 1842 by the English poet Lady Emmeline Stuart-Wortley called "The Maiden of Moscow",[12] but in astronomy the term outer space found its application for the first time in 1845 by Alexander von Humboldt.[13] The term was eventually popularized through the writings of H. G. Wells after 1901.[14] Theodore von Kármán used the term of free space to name the space of altitudes above Earth where spacecrafts reach conditions sufficiently free from atmospheric drag, differentiating it from airspace, identifying a legal space above territories free from the sovereign jurisdiction of countries. This definition of the boundary to outer space became known as the Kármán line.[15]

"Spaceborne" denotes existing in outer space, especially if carried by a spacecraft;[16][17] similarly, "space-based" means based in outer space or on a planet or moon.[18]

Formation and state

[edit]

The size of the whole universe is unknown, and it might be infinite in extent.[19] According to the Big Bang theory, the very early universe was an extremely hot and dense state about 13.8 billion years ago[20] which rapidly expanded. About 380,000 years later the universe had cooled sufficiently to allow protons and electrons to combine and form hydrogen—the so-called recombination epoch. When this happened, matter and energy became decoupled, allowing photons to travel freely through the continually expanding space.[21] Matter that remained following the initial expansion has since undergone gravitational collapse to create stars, galaxies and other astronomical objects, leaving behind a deep vacuum that forms what is now called outer space.[22] As light has a finite velocity, this theory constrains the size of the directly observable universe.[21]

The present day shape of the universe has been determined from measurements of the cosmic microwave background using satellites like the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe. These observations indicate that the spatial geometry of the observable universe is "flat", meaning that photons on parallel paths at one point remain parallel as they travel through space to the limit of the observable universe, except for local gravity.[23] The flat universe, combined with the measured mass density of the universe and the accelerating expansion of the universe, indicates that space has a non-zero vacuum energy, which is called dark energy.[24]

Estimates put the average energy density of the present day universe at the equivalent of 5.9 protons per cubic meter, including dark energy, dark matter, and baryonic matter (ordinary matter composed of atoms). The atoms account for only 4.6% of the total energy density, or a density of one proton per four cubic meters.[25] The density of the universe is clearly not uniform; it ranges from relatively high density in galaxies—including very high density in structures within galaxies, such as planets, stars, and black holes—to conditions in vast voids that have much lower density, at least in terms of visible matter.[26] Unlike matter and dark matter, dark energy seems not to be concentrated in galaxies: although dark energy may account for a majority of the mass-energy in the universe, dark energy's influence is 5 orders of magnitude smaller than the influence of gravity from matter and dark matter within the Milky Way.[27]

Environment

[edit]

Outer space is the closest known approximation to a perfect vacuum. It has effectively no friction, allowing stars, planets, and moons to move freely along their orbits. The deep vacuum of intergalactic space is not devoid of matter, as it contains a few hydrogen atoms per cubic meter.[29] By comparison, the air humans breathe contains about 1025 molecules per cubic meter.[30][31] The low density of matter in outer space means that electromagnetic radiation can travel great distances without being scattered: the mean free path of a photon in intergalactic space is about 1023 km, or 10 billion light years.[32] In spite of this, extinction, which is the absorption and scattering of photons by dust and gas, is an important factor in galactic and intergalactic astronomy.[33]

Stars, planets, and moons retain their atmospheres by gravitational attraction. Atmospheres have no clearly delineated upper boundary: the density of atmospheric gas gradually decreases with distance from the object until it becomes indistinguishable from outer space.[34] The Earth's atmospheric pressure drops to about 0.032 Pa at 100 kilometres (62 miles) of altitude,[35] compared to 100,000 Pa for the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition of standard pressure. Above this altitude, isotropic gas pressure rapidly becomes insignificant when compared to radiation pressure from the Sun and the dynamic pressure of the solar wind. The thermosphere in this range has large gradients of pressure, temperature and composition, and varies greatly due to space weather.[36]

The temperature of outer space is measured in terms of the kinetic activity of the gas,[37] as it is on Earth. The radiation of outer space has a different temperature than the kinetic temperature of the gas, meaning that the gas and radiation are not in thermodynamic equilibrium.[38][39] All of the observable universe is filled with photons that were created during the Big Bang, which is known as the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB). (There is quite likely a correspondingly large number of neutrinos called the cosmic neutrino background.[40]) The current black body temperature of the background radiation is about 2.7 K (−270 °C; −455 °F).[41] The gas temperatures in outer space can vary widely. For example, the temperature in the Boomerang Nebula is 1 K (−272 °C; −458 °F),[42] while the solar corona reaches temperatures over 1,200,000–2,600,000 K (2,200,000–4,700,000 °F).[43]

Magnetic fields have been detected in the space around many classes of celestial objects. Star formation in spiral galaxies can generate small-scale dynamos, creating turbulent magnetic field strengths of around 5–10 μG. The Davis–Greenstein effect causes elongated dust grains to align themselves with a galaxy's magnetic field, resulting in weak optical polarization. This has been used to show ordered magnetic fields that exist in several nearby galaxies. Magneto-hydrodynamic processes in active elliptical galaxies produce their characteristic jets and radio lobes. Non-thermal radio sources have been detected even among the most distant high-z sources, indicating the presence of magnetic fields.[44]

Outside a protective atmosphere and magnetic field, there are few obstacles to the passage through space of energetic subatomic particles known as cosmic rays. These particles have energies ranging from about 106 eV up to an extreme 1020 eV of ultra-high-energy cosmic rays.[45] The peak flux of cosmic rays occurs at energies of about 109 eV, with approximately 87% protons, 12% helium nuclei and 1% heavier nuclei. In the high energy range, the flux of electrons is only about 1% of that of protons.[46] Cosmic rays can damage electronic components and pose a health threat to space travelers.[47]

Scents retained from low Earth orbit, when returning from extravehicular activity, have a burned, metallic odor, similar to the scent of arc welding fumes. This results from oxygen in low Earth orbit, which clings to suits and equipment.[48][49][50] Other regions of space could have very different odors, like that of different alcohols in molecular clouds.[51]

Human access

[edit]Effect on biology and human bodies

[edit]

Despite the harsh environment, several life forms have been found that can withstand extreme space conditions for extended periods. Species of lichen carried on the ESA BIOPAN facility survived exposure for ten days in 2007.[52] Seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum germinated after being exposed to space for 1.5 years.[53] A strain of Bacillus subtilis has survived 559 days when exposed to low Earth orbit or a simulated Martian environment.[54]

The lithopanspermia hypothesis suggests that rocks ejected into outer space from life-harboring planets may successfully transport life forms to another habitable world. A conjecture is that just such a scenario occurred early in the history of the Solar System, with potentially microorganism-bearing rocks being exchanged between Venus, Earth, and Mars.[55] Because bacteria can survive for millions of years, it is at least theoretically possible for Galactic-scale panspermia to occur.[56]

Vacuum

[edit]The lack of pressure in space is the most immediate dangerous characteristic of space to humans. Pressure decreases above Earth, reaching a level at an altitude of around 19.14 km (11.89 mi) that matches the vapor pressure of water at the temperature of the human body. This pressure level is called the Armstrong line, named after American physician Harry G. Armstrong.[57] At or above the Armstrong line, fluids in the throat and lungs boil away. More specifically, exposed bodily liquids such as saliva, tears, and liquids in the lungs boil away. Hence, at this altitude, human survival requires a pressure suit, or a pressurized capsule.[58]

Out in space, sudden exposure of an unprotected human to very low pressure, such as during a rapid decompression, can cause pulmonary barotrauma—a rupture of the lungs, due to the large pressure differential between inside and outside the chest.[59] Even if the subject's airway is fully open, the flow of air through the windpipe may be too slow to prevent the rupture.[60] Rapid decompression can rupture eardrums and sinuses, bruising and blood seep can occur in soft tissues, and shock can cause an increase in oxygen consumption that leads to hypoxia.[61]

As a consequence of rapid decompression, oxygen dissolved in the blood empties into the lungs to try to equalize the partial pressure gradient. Once the deoxygenated blood arrives at the brain, humans lose consciousness after a few seconds and die of hypoxia within minutes.[62] Blood and other body fluids boil when the pressure drops below 6.3 kilopascals (1 psi), and this condition is called ebullism.[63] The steam may bloat the body to twice its normal size and slow circulation, but tissues are elastic and porous enough to prevent rupture. Ebullism is slowed by the pressure containment of blood vessels, so some blood remains liquid.[64][65]

Swelling and ebullism can be reduced by containment in a pressure suit. The Crew Altitude Protection Suit (CAPS), a fitted elastic garment designed in the 1960s for astronauts, prevents ebullism at pressures as low as 2 kilopascals (0.3 psi).[66] Supplemental oxygen is needed at 8 km (5 mi) to provide enough oxygen for breathing and to prevent water loss, while above 20 km (12 mi) pressure suits are essential to prevent ebullism.[67] Most space suits use around 30–39 kilopascals (4–6 psi) of pure oxygen, about the same as the partial pressure of oxygen at the Earth's surface. This pressure is high enough to prevent ebullism, but evaporation of nitrogen dissolved in the blood could still cause decompression sickness and gas embolisms if not managed.[68]

Weightlessness and radiation

[edit]Humans evolved for life in Earth gravity, and exposure to weightlessness has been shown to have deleterious effects on human health. Initially, more than 50% of astronauts experience space motion sickness. This can cause nausea and vomiting, vertigo, headaches, lethargy, and overall malaise. The duration of space sickness varies, but it typically lasts for 1–3 days, after which the body adjusts to the new environment. Longer-term exposure to weightlessness results in muscle atrophy and deterioration of the skeleton, or spaceflight osteopenia. These effects can be minimized through a regimen of exercise.[69] Other effects include fluid redistribution, slowing of the cardiovascular system, decreased production of red blood cells, balance disorders, and a weakening of the immune system. Lesser symptoms include loss of body mass, nasal congestion, sleep disturbance, and puffiness of the face.[70]

During long-duration space travel, radiation can pose an acute health hazard. Exposure to high-energy, ionizing cosmic rays can result in fatigue, nausea, vomiting, as well as damage to the immune system and changes to the white blood cell count. Over longer durations, symptoms include an increased risk of cancer, plus damage to the eyes, nervous system, lungs and the gastrointestinal tract.[71] On a round-trip Mars mission lasting three years, a large fraction of the cells in an astronaut's body would be traversed and potentially damaged by high energy nuclei.[72] The energy of such particles is significantly diminished by the shielding provided by the walls of a spacecraft and can be further diminished by water containers and other barriers. The impact of the cosmic rays upon the shielding produces additional radiation that can affect the crew. Further research is needed to assess the radiation hazards and determine suitable countermeasures.[73]

Boundary

[edit]

The transition between Earth's atmosphere and outer space lacks a well-defined physical boundary, with the air pressure steadily decreasing with altitude until it mixes with the solar wind. Various definitions for a practical boundary have been proposed, ranging from 30 km (19 mi) out to 1,600,000 km (990,000 mi).[15] In 2009, measurements of the direction and speed of ions in the atmosphere were made from a sounding rocket. The altitude of 118 km (73.3 mi) above Earth was the midpoint for charged particles transitioning from the gentle winds of the Earth's atmosphere to the more extreme flows of outer space. The latter can reach velocities well over 268 m/s (880 ft/s).[74][75]

High-altitude aircraft, such as high-altitude balloons have reached altitudes above Earth of up to 50 km.[76] Up until 2021, the United States designated people who travel above an altitude of 50 mi (80 km) as astronauts.[77] Astronaut wings are now only awarded to spacecraft crew members that "demonstrated activities during flight that were essential to public safety, or contributed to human space flight safety".[78]

The region between airspace and outer space is termed "near space". There is no legal definition for this extent, but typically this is the altitude range from 20 to 100 km (12 to 62 mi).[79] For safety reasons, commercial aircraft are typically limited to altitudes of 12 km (7.5 mi), and air navigation services only extend to 18 to 20 km (11 to 12 mi).[79] The upper limit of the range is the Kármán line, where astrodynamics must take over from aerodynamics in order to achieve flight.[80] This range includes the stratosphere, mesosphere and lower thermosphere layers of the Earth's atmosphere.[81]

Larger ranges for near space are used by some authors, such as 18 to 160 km (11 to 99 mi).[82] These extend to the altitudes where orbital flight in very low Earth orbits becomes practical.[82] Spacecraft have entered into a highly elliptical orbit with a perigee as low as 80 to 90 km (50 to 56 mi), surviving for multiple orbits.[83] At an altitude of 120 km (75 mi),[83] descending spacecraft begin atmospheric entry as atmospheric drag becomes noticeable. For spaceplanes such as NASA's Space Shuttle, this begins the process of switching from steering with thrusters to maneuvering with aerodynamic control surfaces.[84]

The Kármán line, established by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, and used internationally by the United Nations,[15] is set at an altitude of 100 km (62 mi) as a working definition for the boundary between aeronautics and astronautics. This line is named after Theodore von Kármán, who argued for an altitude where a vehicle would have to travel faster than orbital velocity to derive sufficient aerodynamic lift from the atmosphere to support itself,[8][9] which he calculated to be at an altitude of about 83.8 km (52.1 mi).[76] This distinguishes altitudes below as the region of aerodynamics and airspace, and above as the space of astronautics and free space.[15]

There is no internationally recognized legal altitude limit on national airspace, although the Kármán line is the most frequently used for this purpose. Objections have been made to setting this limit too high, as it could inhibit space activities due to concerns about airspace violations.[83] It has been argued for setting no specified singular altitude in international law, instead applying different limits depending on the case, in particular based on the craft and its purpose. Increased commercial and military sub-orbital spaceflight has raised the issue of where to apply laws of airspace and outer space.[82][80] Spacecraft have flown over foreign countries as low as 30 km (19 mi), as in the example of the Space Shuttle.[76]

Legal status

[edit]

The Outer Space Treaty provides the basic framework for international space law. It covers the legal use of outer space by nation states, and includes in its definition of outer space, the Moon, and other celestial bodies. The treaty states that outer space is free for all nation states to explore and is not subject to claims of national sovereignty, calling outer space the "province of all mankind". This status as a common heritage of mankind has been used, though not without opposition, to enforce the right to access and shared use of outer space for all nations equally, particularly non-spacefaring nations.[85] It prohibits the deployment of nuclear weapons in outer space. The treaty was passed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1963 and signed in 1967 by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the United States of America (USA), and the United Kingdom (UK). As of 2017, 105 state parties have either ratified or acceded to the treaty. An additional 25 states signed the treaty, without ratifying it.[86][87]

Since 1958, outer space has been the subject of multiple United Nations resolutions. Of these, more than 50 have been concerning the international co-operation in the peaceful uses of outer space and preventing an arms race in space.[88] Four additional space law treaties have been negotiated and drafted by the UN's Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. Still, there remains no legal prohibition against deploying conventional weapons in space, and anti-satellite weapons have been successfully tested by the USA, USSR, China,[89] and in 2019, India.[90] The 1979 Moon Treaty turned the jurisdiction of all heavenly bodies (including the orbits around such bodies) over to the international community. The treaty has not been ratified by any nation that currently practices human spaceflight.[91]

In 1976, eight equatorial states (Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, The Republic of the Congo, Zaire, Uganda, Kenya, and Indonesia) met in Bogotá, Colombia: with their "Declaration of the First Meeting of Equatorial Countries", or the Bogotá Declaration, they claimed control of the segment of the geosynchronous orbital path corresponding to each country.[92] These claims are not internationally accepted.[93]

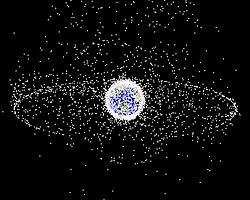

An increasing issue of international space law and regulation has been the dangers of the growing number of space debris.[94]

Earth orbit

[edit]

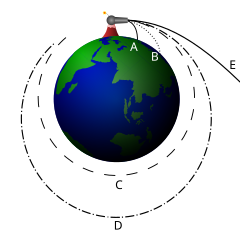

When a rocket is launched to achieve orbit, its thrust must both counter gravity and accelerate it to orbital speed. After the rocket terminates its thrust, it follows an arc-like trajectory back toward the ground under the influence of the Earth's gravitational force. In a closed orbit, this arc will turn into an elliptical loop around the planet. That is, a spacecraft successfully enters Earth orbit when its acceleration due to gravity pulls the craft down just enough to prevent its momentum from carrying it off into outer space.[95]

For a low Earth orbit, orbital speed is about 7.8 km/s (17,400 mph);[96] by contrast, the fastest piloted airplane speed ever achieved (excluding speeds achieved by deorbiting spacecraft) was 2.2 km/s (4,900 mph) in 1967 by the North American X-15.[97] The upper limit of orbital speed at 11.2 km/s (25,100 mph) is the velocity required to pull free from Earth altogether and enter into a heliocentric orbit.[98] The energy required to reach Earth orbital speed at an altitude of 600 km (370 mi) is about 36 MJ/kg, which is six times the energy needed merely to climb to the corresponding altitude.[99]

Very low Earth orbit (VLEO) has been defined as orbits that have a mean altitude below 450 km (280 mi), which can be better suited for Earth observation with small satellites.[100] Low Earth orbits in general range in altitude from 180 to 2,000 km (110 to 1,240 mi) and are used for scientific satellites. Medium Earth orbits extends from 2,000 to 35,780 km (1,240 to 22,230 mi), which are favorable orbits for navigation and specialized satellites. Above 35,780 km (22,230 mi) are the high Earth orbits used for weather and some communication satellites.[101]

Spacecraft in orbit with a perigee below about 2,000 km (1,200 mi) (low Earth orbit) are subject to drag from the Earth's atmosphere,[102] which decreases the orbital altitude. The rate of orbital decay depends on the satellite's cross-sectional area and mass, as well as variations in the air density of the upper atmosphere, which is significantly effected by space weather.[103] At altitudes above 800 km (500 mi), orbital lifetime is measured in centuries.[104] Below about 300 km (190 mi), decay becomes more rapid with lifetimes measured in days. Once a satellite descends to 180 km (110 mi), it has only hours before it vaporizes in the atmosphere.[105]

Radiation in orbit around Earth is concentrated in Van Allen radiation belts, which trap solar and galactic radiation. Radiation is a threat to astronauts and space systems. It is difficult to shield against and space weather makes the radiation environment variable. The radiation belts are equatorial toroidal regions, which are bent towards Earth's poles, with the South Atlantic Anomaly being the region where charged particles approach Earth closest.[106][107] The innermost radiation belt, the inner Van Allen belt, has its intensity peak at altitudes above the equator of half an Earth radius,[108] centered at about 3000 km,[109] increasing from the upper edge of low Earth orbit which it overlaps.[110][111][112]

Regions

[edit]Regions near the Earth

[edit]The outermost layer of the Earth's atmosphere is termed the exosphere. It extends outward from the thermopause, which lies at an altitude that varies from 250 to 500 kilometres (160 to 310 mi), depending on the incidence of solar radiation. Beyond this altitude, collisions between molecules are negligible and the atmosphere joins with interplanetary space.[113] The region in proximity to the Earth is home to a multitude of Earth–orbiting satellites and has been subject to extensive studies. For identification purposes, this volume is divided into overlapping regions of space.[114][115][116][117]

Near-Earth space is the region of space extending from low Earth orbits out to geostationary orbits.[114] This region includes the major orbits for artificial satellites and is the site of most of humanity's space activity. The region has seen high levels of space debris, sometimes dubbed space pollution, threatening nearby space activity.[114] Some of this debris re-enters Earth's atmosphere periodically.[118] Although it meets the definition of outer space, the atmospheric density inside low-Earth orbital space, the first few hundred kilometers above the Kármán line, is still sufficient to produce significant drag on satellites.[105]

Geospace is a region of space that includes Earth's upper atmosphere and magnetosphere.[115] The Van Allen radiation belts lie within the geospace. The outer boundary of geospace is the magnetopause, which forms an interface between the Earth's magnetosphere and the solar wind. The inner boundary is the ionosphere.[120][121]

The variable space-weather conditions of geospace are affected by the behavior of the Sun and the solar wind; the subject of geospace is interlinked with heliophysics—the study of the Sun and its impact on the planets of the Solar System.[122] The day-side magnetopause is compressed by solar-wind pressure—the subsolar distance from the center of the Earth is typically 10 Earth radii. On the night side, the solar wind stretches the magnetosphere to form a magnetotail that sometimes extends out to more than 100–200 Earth radii.[123][124] For roughly four days of each month, the lunar surface is shielded from the solar wind as the Moon passes through the magnetotail.[125]

Geospace is populated by electrically charged particles at very low densities, the motions of which are controlled by the Earth's magnetic field. These plasmas form a medium from which storm-like disturbances powered by the solar wind can drive electrical currents into the Earth's upper atmosphere. Geomagnetic storms can disturb two regions of geospace, the radiation belts and the ionosphere. These storms increase fluxes of energetic electrons that can permanently damage satellite electronics, interfering with shortwave radio communication and GPS location and timing.[126] Magnetic storms can be a hazard to astronauts, even in low Earth orbit. They create aurorae seen at high latitudes in an oval surrounding the geomagnetic poles.[127]

XGEO space is a concept used by the USA to refer to the space of high Earth orbits, with the 'X' being some multiple of geosynchronous orbit (GEO) at approximately 35,786 km (22,236 mi).[116] Hence, the L2 Earth-Moon Lagrange point at 448,900 km (278,934 mi) is approximately 10.67 XGEO.[128] Translunar space is the region of lunar transfer orbits, between the Moon and Earth.[129] Cislunar space is a region outside of Earth that includes lunar orbits, the Moon's orbital space around Earth and the Earth-Moon Lagrange points.[117]

The region where a body's gravitational potential remains dominant against gravitational potentials from other bodies, is the body's sphere of influence or gravity well, mostly described with the Hill sphere model.[130] In the case of Earth this includes all space from the Earth to a distance of roughly 1% of the mean distance from Earth to the Sun,[131] or 1.5 million km (0.93 million mi). Beyond Earth's Hill sphere extends along Earth's orbital path its orbital and co-orbital space. This space is co-populated by groups of co-orbital Near-Earth Objects (NEOs), such as horseshoe librators and Earth trojans, with some NEOs at times becoming temporary satellites and quasi-moons to Earth.[132]

Deep space is defined by the United States government as all of outer space which lies further from Earth than a typical low-Earth-orbit, thus assigning the Moon to deep-space.[133] Other definitions vary the starting point of deep-space from, "That which lies beyond the orbit of the moon," to "That which lies beyond the farthest reaches of the Solar System itself."[134][135][136] The International Telecommunication Union responsible for radio communication, including with satellites, defines deep-space as, "distances from the Earth equal to, or greater than, 2 million km (1.2 million mi),"[137] which is about five times the Moon's orbital distance, but which distance is also far less than the distance between Earth and any adjacent planet.[138]

Interplanetary space

[edit]

Interplanetary space within the Solar System is dominated by the gravitation of the Sun, outside the gravitational spheres of influence of the planets.[139] Interplanetary space extends well beyond the orbit of the outermost planet Neptune, all the way out to where the influence of the galactic environment starts to dominate over the Sun and its solar wind producing the heliopause at 110 to 160 AU.[140] The heliopause deflects away low-energy galactic cosmic rays, and its distance and strength varies depending on the activity level of the solar wind.[141][142] The solar wind is a continuous stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun which creates a very tenuous atmosphere (the heliosphere) for billions of kilometers into space. This wind has a particle density of 5–10 protons/cm3 and is moving at a velocity of 350–400 km/s (780,000–890,000 mph).[143]

The region of interplanetary space is a nearly total vacuum, with a mean free path of about one astronomical unit at the orbital distance of the Earth. This space is not completely empty, but is sparsely filled with cosmic rays, which include ionized atomic nuclei and various subatomic particles. There is gas, plasma and dust,[144] small meteors, and several dozen types of organic molecules discovered to date by microwave spectroscopy.[145] Collectively, this matter is termed the interplanetary medium.[140] A cloud of interplanetary dust is visible at night as a faint band called the zodiacal light.[146]

Interplanetary space contains the magnetic field generated by the Sun.[143] There are magnetospheres generated by planets such as Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury and the Earth that have their own magnetic fields. These are shaped by the influence of the solar wind into the approximation of a teardrop shape, with the long tail extending outward behind the planet. These magnetic fields can trap particles from the solar wind and other sources, creating belts of charged particles such as the Van Allen radiation belts. Planets without magnetic fields, such as Mars, have their atmospheres gradually eroded by the solar wind.[147]

Interstellar space

[edit]

Interstellar space is the physical space outside of the bubbles of plasma known as astrospheres, formed by stellar winds originating from individual stars.[148] It is the space between the stars or stellar systems within a nebula or galaxy.[149] Interstellar space contains an interstellar medium of sparse matter and radiation. The boundary between an astrosphere and interstellar space is known as an astropause. For the Sun, the astrosphere and astropause are called the heliosphere and heliopause, respectively.[150]

Approximately 70% of the mass of the interstellar medium consists of lone hydrogen atoms; most of the remainder consists of helium atoms. This is enriched with trace amounts of heavier atoms formed through stellar nucleosynthesis. These atoms are ejected into the interstellar medium by stellar winds or when evolved stars begin to shed their outer envelopes such as during the formation of a planetary nebula.[151] The cataclysmic explosion of a supernova propagates shock waves of stellar ejecta outward, distributing it throughout the interstellar medium, including the heavy elements previously formed within the star's core.[152] The density of matter in the interstellar medium can vary considerably: the average is around 106 particles per m3,[153] but cold molecular clouds can hold 108–1012 per m3.[38][151]

A number of molecules exist in interstellar space, which can form dust particles as tiny as 0.1 μm.[154] The tally of molecules discovered through radio astronomy is steadily increasing at the rate of about four new species per year. Large regions of higher density matter known as molecular clouds allow chemical reactions to occur, including the formation of organic polyatomic species. Much of this chemistry is driven by collisions. Energetic cosmic rays penetrate the cold, dense clouds and ionize hydrogen and helium, resulting, for example, in the trihydrogen cation. An ionized helium atom can then split relatively abundant carbon monoxide to produce ionized carbon, which in turn can lead to organic chemical reactions.[155]

The local interstellar medium is a region of space within 100 pc of the Sun, which is of interest both for its proximity and for its interaction with the Solar System. This volume nearly coincides with a region of space known as the Local Bubble, which is characterized by a lack of dense, cold clouds. It forms a cavity in the Orion Arm of the Milky Way Galaxy, with dense molecular clouds lying along the borders, such as those in the constellations of Ophiuchus and Taurus. The actual distance to the border of this cavity varies from 60 to 250 pc or more. This volume contains about 104–105 stars and the local interstellar gas counterbalances the astrospheres that surround these stars, with the volume of each sphere varying depending on the local density of the interstellar medium. The Local Bubble contains dozens of warm interstellar clouds with temperatures of up to 7,000 K and radii of 0.5–5 pc.[156]

When stars are moving at sufficiently high peculiar velocities, their astrospheres can generate bow shocks as they collide with the interstellar medium. For decades it was assumed that the Sun had a bow shock. In 2012, data from Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) and NASA's Voyager probes showed that the Sun's bow shock does not exist. Instead, these authors argue that a subsonic bow wave defines the transition from the solar wind flow to the interstellar medium.[157][158] A bow shock is a third boundary characteristic of an astrosphere, lying outside the termination shock and the astropause.[158]

Intergalactic space

[edit]

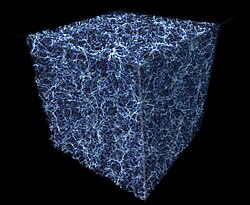

Intergalactic space is the physical space between galaxies. Studies of the large-scale distribution of galaxies show that the universe has a foam-like structure, with groups and clusters of galaxies lying along filaments that occupy about a tenth of the total space. The remainder forms cosmic voids that are mostly empty of galaxies. Typically, a void spans a distance of 7–30 megaparsecs.[159]

Surrounding and stretching between galaxies is the intergalactic medium (IGM). This rarefied plasma[160] is organized in a galactic filamentary structure.[161] The diffuse photoionized gas contains filaments of higher density, about one atom per cubic meter,[162] which is 5–200 times the average density of the universe.[163] The IGM is inferred to be mostly primordial in composition, with 76% hydrogen by mass, and enriched with higher mass elements from high-velocity galactic outflows.[164]

As gas falls into the intergalactic medium from the voids, it heats up to temperatures of 105 K to 107 K.[4] At these temperatures, it is called the warm–hot intergalactic medium (WHIM). Although the plasma is very hot by terrestrial standards, 105 K is often called "warm" in astrophysics. Computer simulations and observations indicate that up to half of the atomic matter in the universe might exist in this warm–hot, rarefied state.[163][165][166] When gas falls from the filamentary structures of the WHIM into the galaxy clusters at the intersections of the cosmic filaments, it can heat up even more, reaching temperatures of 108 K and above in the so-called intracluster medium (ICM).[167]

History of discovery

[edit]In 350 BCE, Greek philosopher Aristotle suggested that nature abhors a vacuum, a principle that became known as the horror vacui. This concept built upon a 5th-century BCE ontological argument by the Greek philosopher Parmenides, who denied the possible existence of a void in space.[168] Based on this idea that a vacuum could not exist, in the West it was widely held for many centuries that space could not be empty.[169] As late as the 17th century, the French philosopher René Descartes argued that the entirety of space must be filled.[170]

In ancient China, the 2nd-century astronomer Zhang Heng became convinced that space must be infinite, extending well beyond the mechanism that supported the Sun and the stars. The surviving books of the Hsüan Yeh school said that the heavens were boundless, "empty and void of substance". Likewise, the "sun, moon, and the company of stars float in the empty space, moving or standing still".[171]

The Italian scientist Galileo Galilei knew that air has mass and so was subject to gravity. In 1640, he demonstrated that an established force resisted the formation of a vacuum. It would remain for his pupil Evangelista Torricelli to create an apparatus that would produce a partial vacuum in 1643. This experiment resulted in the first mercury barometer and created a scientific sensation in Europe. Torricelli suggested that since air has weight, then air pressure should decrease with altitude.[172] The French mathematician Blaise Pascal proposed an experiment to test this hypothesis.[173] In 1648, his brother-in-law, Florin Périer, repeated the experiment on the Puy de Dôme mountain in central France and found that the column was shorter by three inches. This decrease in pressure was further demonstrated by carrying a half-full balloon up a mountain and watching it gradually expand, then contract upon descent.[174]

In 1650, German scientist Otto von Guericke constructed the first vacuum pump: a device that would further refute the principle of horror vacui. He correctly noted that the atmosphere of the Earth surrounds the planet like a shell, with the density gradually declining with altitude. He concluded that there must be a vacuum between the Earth and the Moon.[175]

In the 15th century, German theologian Nicolaus Cusanus speculated that the universe lacked a center and a circumference. He believed that the universe, while not infinite, could not be held as finite as it lacked any bounds within which it could be contained.[176] These ideas led to speculations as to the infinite dimension of space by the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno in the 16th century. He extended the Copernican heliocentric cosmology to the concept of an infinite universe filled with a substance he called aether, which did not resist the motion of heavenly bodies.[177] English philosopher William Gilbert arrived at a similar conclusion, arguing that the stars are visible to us only because they are surrounded by a thin aether or a void.[178] This concept of an aether originated with ancient Greek philosophers, including Aristotle, who conceived of it as the medium through which the heavenly bodies move.[179]

The concept of a universe filled with a luminiferous aether retained support among some scientists until the early 20th century. This form of aether was viewed as the medium through which light could propagate.[180] In 1887, the Michelson–Morley experiment tried to detect the Earth's motion through this medium by looking for changes in the speed of light depending on the direction of the planet's motion. The null result indicated something was wrong with the concept. The idea of the luminiferous aether was then abandoned. It was replaced by Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity, which holds that the speed of light in a vacuum is a fixed constant, independent of the observer's motion or frame of reference.[181][182]

The first professional astronomer to support the concept of an infinite universe was the Englishman Thomas Digges in 1576.[183] But the scale of the universe remained unknown until the first successful measurement of the distance to a nearby star in 1838 by the German astronomer Friedrich Bessel. He showed that the star system 61 Cygni had a parallax of just 0.31 arcseconds (compared to the modern value of 0.287″). This corresponds to a distance of over 10 light years.[184] In 1917, Heber Curtis noted that novae in spiral nebulae were, on average, 10 magnitudes fainter than galactic novae, suggesting that the former are 100 times further away.[185] The distance to the Andromeda Galaxy was determined in 1923 by American astronomer Edwin Hubble by measuring the brightness of cepheid variables in that galaxy, a new technique discovered by Henrietta Leavitt.[186] This established that the Andromeda Galaxy, and by extension all galaxies, lay well outside the Milky Way.[187] With this Hubble formulated the Hubble constant, which allowed for the first time a calculation of the age of the Universe and size of the Observable Universe, starting at 2 billion years and 280 million light-years. This became increasingly precise with better measurements, until 2006 when data of the Hubble Space Telescope allowed a very accurate calculation of the age of the Universe and size of the Observable Universe.[188]

The modern concept of outer space is based on the "Big Bang" cosmology, first proposed in 1931 by the Belgian physicist Georges Lemaître.[189] This theory holds that the universe originated from a state of extreme energy density that has since undergone continuous expansion.[190]

The earliest known estimate of the temperature of outer space was by the Swiss physicist Charles É. Guillaume in 1896. Using the estimated radiation of the background stars, he concluded that space must be heated to a temperature of 5–6 K. British physicist Arthur Eddington made a similar calculation to derive a temperature of 3.18 K in 1926. German physicist Erich Regener used the total measured energy of cosmic rays to estimate an intergalactic temperature of 2.8 K in 1933.[191] American physicists Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman predicted 5 K for the temperature of space in 1948, based on the gradual decrease in background energy following the then-new Big Bang theory.[191]

Exploration

[edit]

For most of human history, space was explored by observations made from the Earth's surface—initially with the unaided eye and then with the telescope. Before reliable rocket technology, the closest that humans had come to reaching outer space was through balloon flights. In 1935, the American Explorer II crewed balloon flight reached an altitude of 22 km (14 mi).[193] This was greatly exceeded in 1942 when the third launch of the German A-4 rocket climbed to an altitude of about 80 km (50 mi). In 1957, the uncrewed satellite Sputnik 1 was launched by a Russian R-7 rocket, achieving Earth orbit at an altitude of 215–939 kilometres (134–583 mi).[194] This was followed by the first human spaceflight in 1961, when Yuri Gagarin was sent into orbit on Vostok 1. The first humans to escape low Earth orbit were Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders in 1968 on board the American Apollo 8, which achieved lunar orbit[195] and reached a maximum distance of 377,349 km (234,474 mi) from the Earth.[196]

The first spacecraft to reach escape velocity was the Soviet Luna 1, which performed a fly-by of the Moon in 1959.[197] In 1961, Venera 1 became the first planetary probe. It revealed the presence of the solar wind and performed the first fly-by of Venus, although contact was lost before reaching Venus. The first successful planetary mission was the 1962 fly-by of Venus by Mariner 2.[198] The first fly-by of Mars was by Mariner 4 in 1964. Since that time, uncrewed spacecraft have successfully examined each of the Solar System's planets, as well their moons and many minor planets and comets. They remain a fundamental tool for the exploration of outer space, as well as for observation of the Earth.[199] In August 2012, Voyager 1 became the first man-made object to leave the Solar System and enter interstellar space.[200]

Application

[edit]

Outer space has become an important element of global society. It provides multiple applications that are beneficial to the economy and scientific research.

The placing of artificial satellites in Earth orbit has produced numerous benefits and has become the dominating sector of the space economy. They allow relay of long-range communications like television, provide a means of precise navigation, and permit direct monitoring of weather conditions and remote sensing of the Earth. The latter role serves a variety of purposes, including tracking soil moisture for agriculture, prediction of water outflow from seasonal snow packs, detection of diseases in plants and trees, and surveillance of military activities.[201] They facilitate the discovery and monitoring of climate change influences.[202] Satellites make use of the significantly reduced drag in space to stay in stable orbits, allowing them to efficiently span the whole globe, compared to for example stratospheric balloons or high-altitude platform stations, which have other benefits.[203]

The absence of air makes outer space an ideal location for astronomy at all wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. This is evidenced by the pictures sent back by the Hubble Space Telescope, allowing light from more than 13 billion years ago—almost to the time of the Big Bang—to be observed.[204] Not every location in space is ideal for a telescope. The interplanetary zodiacal dust emits a diffuse near-infrared radiation that can mask the emission of faint sources such as extrasolar planets. Moving an infrared telescope out past the dust increases its effectiveness.[205] Likewise, a site like the Daedalus crater on the far side of the Moon could shield a radio telescope from the radio frequency interference that hampers Earth-based observations.[206]

The deep vacuum of space could make it an attractive environment for certain industrial processes, such as those requiring ultraclean surfaces.[208] Like asteroid mining, space manufacturing would require a large financial investment with little prospect of immediate return.[209] An important factor in the total expense is the high cost of placing mass into Earth orbit: $9,000–$31,000 per kg, according to a 2006 estimate (allowing for inflation since then).[210] The cost of access to space has declined since 2013. Partially reusable rockets such as the Falcon 9 have lowered access to space below $3,500 per kg. With these new rockets the cost to send materials into space remains prohibitively high for many industries. Proposed concepts for addressing this issue include, fully reusable launch systems, non-rocket spacelaunch, momentum exchange tethers, and space elevators.[211]

Interstellar travel for a human crew remains at present only a theoretical possibility. The distances to the nearest stars mean it would require new technological developments and the ability to safely sustain crews for journeys lasting several decades. For example, the Daedalus Project study, which proposed a spacecraft powered by the fusion of deuterium and helium-3, would require 36 years to reach the "nearby" Alpha Centauri system. Other proposed interstellar propulsion systems include light sails, ramjets, and beam-powered propulsion. More advanced propulsion systems could use antimatter as a fuel, potentially reaching relativistic velocities.[212]

From the Earth's surface, the ultracold temperature of outer space can be used as a renewable cooling technology for various applications on Earth through passive daytime radiative cooling.[213][214] This enhances longwave infrared (LWIR) thermal radiation heat transfer through the atmosphere's infrared window into outer space, lowering ambient temperatures.[215][216] Photonic metamaterials can be used to suppress solar heating.[217]

See also

[edit]- Absolute space and time

- Artemis Accords

- List of government space agencies

- List of topics in space

- Olbers' paradox

- Outline of space science

- Panspermia

- Space art

- Space and survival

- Space race

- Space station

- Space technology

- Timeline of knowledge about the interstellar and intergalactic medium

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- Timeline of spaceflight

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Applicable definitions of outer space, space, and expanse", Merriam-Webster dictionary, retrieved 2024-06-17,

Outer space (n.) space immediately outside the earth's atmosphere.

Space (n.) physical space independent of what occupies it. The region beyond the earth's atmosphere or beyond the solar system.

Expanse (n.) great extent of something spread out. - ^ Roth, A. (2012), Vacuum Technology, Elsevier, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-444-59874-5.

- ^ Chuss, David T. (June 26, 2008), Cosmic Background Explorer, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, archived from the original on 2013-05-09, retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ^ a b Gupta, Anjali; et al. (May 2010), "Detection and Characterization of the Warm-Hot Intergalactic Medium", Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 41: 908, Bibcode:2010AAS...21631808G.

- ^ Freedman & Kaufmann 2005, pp. 573, 599–601, 650–653.

- ^ Trimble, V. (1987), "Existence and nature of dark matter in the universe", Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 25: 425–472, Bibcode:1987ARA&A..25..425T, doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.25.090187.002233, S2CID 123199266.

- ^ "Dark Energy, Dark Matter", NASA Science, archived from the original on June 2, 2013, retrieved May 31, 2013,

It turns out that roughly 68% of the Universe is dark energy. Dark matter makes up about 27%.

- ^ a b O'Leary 2009, p. 84.

- ^ a b "Where does space begin?", Aerospace Engineering, archived from the original on 2015-11-17, retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (November 2001), Space, The Online Etymology Dictionary, archived from the original on 2009-02-24, retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Brady, Maura (October 2007), "Space and the Persistence of Place in "Paradise Lost"", Milton Quarterly, 41 (3): 167–182, doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.2007.00164.x, JSTOR 24461820.

- ^ Stuart Wortley 1841, p. 410.

- ^ Von Humboldt 1845, p. 39.

- ^ Harper, Douglas, "Outer", Online Etymology Dictionary, archived from the original on 2010-03-12, retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ a b c d Betz, Eric (November 27, 2023), "The Kármán Line: Where space begins", Astronomy Magazine, retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "Definition of SPACEBORNE", Merriam-Webster, May 17, 2022, retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ "Spaceborne definition and meaning", Collins English Dictionary, May 17, 2022, retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ "-based", Cambridge Dictionary, 2024, retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ Liddle 2015, pp. 33.

- ^ Planck Collaboration (2014), "Planck 2013 results. I. Overview of products and scientific results", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 571: 1, arXiv:1303.5062, Bibcode:2014A&A...571A...1P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321529, S2CID 218716838.

- ^ a b Turner, Michael S. (September 2009), "Origin of the Universe", Scientific American, 301 (3): 36–43, Bibcode:2009SciAm.301c..36T, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0909-36, PMID 19708526.

- ^ Silk 2000, pp. 105–308.

- ^ WMAP – Shape of the universe, NASA, December 21, 2012, archived from the original on June 1, 2012, retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Sparke & Gallagher 2007, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Wollack, Edward J. (June 24, 2011), What is the Universe Made Of?, NASA, archived from the original on 2016-07-26, retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ Krumm, N.; Brosch, N. (October 1984), "Neutral hydrogen in cosmic voids", Astronomical Journal, 89: 1461–1463, Bibcode:1984AJ.....89.1461K, doi:10.1086/113647.

- ^ Peebles, P.; Ratra, B. (2003), "The cosmological constant and dark energy", Reviews of Modern Physics, 75 (2): 559–606, arXiv:astro-ph/0207347, Bibcode:2003RvMP...75..559P, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.559, S2CID 118961123

- ^ "False Dawn", www.eso.org, retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Tadokoro, M. (1968), "A Study of the Local Group by Use of the Virial Theorem", Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan, 20 (3): 230, Bibcode:1968PASJ...20..230T, doi:10.1093/pasj/20.3.230. This source estimates a density of 7×10−29 g/cm3 for the Local Group. The mass of a hydrogen atom is 1.67×10−24 g, for roughly 40 atoms per cubic meter.

- ^ Borowitz & Beiser 1971.

- ^ Tyson, Patrick (January 2012), The Kinetic Atmosphere: Molecular Numbers (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2013, retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Davies 1977, p. 93.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, E. L. (May 2004), "Interstellar Extinction in the Milky Way Galaxy", in Witt, Adolf N.; Clayton, Geoffrey C.; Draine, Bruce T. (eds.), Astrophysics of Dust, ASP Conference Series, vol. 309, p. 33, arXiv:astro-ph/0401344, Bibcode:2004ASPC..309...33F.

- ^ Chamberlain 1978, p. 2.

- ^ Squire, Tom (September 27, 2000), "U.S. Standard Atmosphere, 1976", Thermal Protection Systems Expert and Material Properties Database, NASA, archived from the original on October 15, 2011, retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ Forbes, Jeffrey M. (2007), "Dynamics of the thermosphere", Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, Series II, 85B: 193–213, Bibcode:2007JMeSJ..85B.193F, doi:10.2151/jmsj.85b.193.

- ^ Spitzer, Lyman Jr. (January 1948), "The Temperature of Interstellar Matter. I", Astrophysical Journal, 107: 6, Bibcode:1948ApJ...107....6S, doi:10.1086/144984.

- ^ a b Prialnik 2000, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Spitzer 1978, p. 28–30.

- ^ Chiaki, Yanagisawa (June 2014), "Looking for Cosmic Neutrino Background", Frontiers in Physics, 2: 30, Bibcode:2014FrP.....2...30Y, doi:10.3389/fphy.2014.00030.

- ^ Fixsen, D. J. (December 2009), "The Temperature of the Cosmic Microwave Background", The Astrophysical Journal, 707 (2): 916–920, arXiv:0911.1955, Bibcode:2009ApJ...707..916F, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/707/2/916, S2CID 119217397.

- ^ ALMA reveals ghostly shape of 'coldest place in the universe', National Radio Astronomy Observatory, October 24, 2013, retrieved 2020-10-07.

- ^ Withbroe, George L. (February 1988), "The temperature structure, mass, and energy flow in the corona and inner solar wind", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 325: 442–467, Bibcode:1988ApJ...325..442W, doi:10.1086/166015.

- ^ Wielebinski, Richard; Beck, Rainer (2010), "Cosmic Magnetic Fields − An Overview", in Block, David L.; Freeman, Kenneth C.; Puerari, Ivânio (eds.), Galaxies and their Masks: A Conference in Honour of K.C. Freeman, FRS, Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 67–82, Bibcode:2010gama.conf...67W, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7317-7_5, ISBN 978-1-4419-7317-7, archived from the original on 2017-09-20.

- ^ Letessier-Selvon, Antoine; Stanev, Todor (July 2011), "Ultrahigh energy cosmic rays", Reviews of Modern Physics, 83 (3): 907–942, arXiv:1103.0031, Bibcode:2011RvMP...83..907L, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.83.907, S2CID 119237295.

- ^ Lang 1999, p. 462.

- ^ Lide 1993, p. 11-217.

- ^ What Does Space Smell Like?, Live Science, July 20, 2012, archived from the original on February 28, 2014, retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Schiffman, Lizzie (July 17, 2013), What Does Space Smell Like, Popular Science, archived from the original on February 24, 2014, retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ "Interesting Fact of the Month 2021", NASA, August 3, 2023, retrieved 2024-09-18.

- ^ Cooper, Keith (January 8, 2024), "What does space smell like?", Space.com, retrieved 2024-09-18.

- ^ Raggio, J.; et al. (May 2011), "Whole Lichen Thalli Survive Exposure to Space Conditions: Results of Lithopanspermia Experiment with Aspicilia fruticulosa", Astrobiology, 11 (4): 281–292, Bibcode:2011AsBio..11..281R, doi:10.1089/ast.2010.0588, PMID 21545267.

- ^ Tepfer, David; et al. (May 2012), "Survival of Plant Seeds, Their UV Screens, and nptII DNA for 18 Months Outside the International Space Station" (PDF), Astrobiology, 12 (5): 517–528, Bibcode:2012AsBio..12..517T, doi:10.1089/ast.2011.0744, PMID 22680697, archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-13, retrieved 2013-05-19.

- ^ Wassmann, Marko; et al. (May 2012), "Survival of Spores of the UV-ResistantBacillus subtilis Strain MW01 After Exposure to Low-Earth Orbit and Simulated Martian Conditions: Data from the Space Experiment ADAPT on EXPOSE-E", Astrobiology, 12 (5): 498–507, Bibcode:2012AsBio..12..498W, doi:10.1089/ast.2011.0772, PMID 22680695.

- ^ Nicholson, W. L. (April 2010), "Towards a General Theory of Lithopanspermia", Astrobiology Science Conference 2010, vol. 1538, pp. 5272–528, Bibcode:2010LPICo1538.5272N.

- ^ Ginsburg, Idan; et al. (2018), "Galactic Panspermia", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 868 (1): L12, arXiv:1810.04307, Bibcode:2018ApJ...868L..12G, doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aaef2d.

- ^ Tarver, William J.; et al. (October 24, 2022), Aerospace Pressure Effects, Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262037, retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ Piantadosi 2003, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Battisti, Amanda S.; et al. (June 27, 2022), Barotrauma, StatPearls Publishing LLC, PMID 29493973, retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ Krebs, Matthew B.; Pilmanis, Andrew A. (November 1996), Human pulmonary tolerance to dynamic over-pressure (PDF), United States Air Force Armstrong Laboratory, archived from the original on 2012-11-30, retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ^ Busby, D. E. (July 1967), "A prospective look at medical problems from hazards of space operations" (PDF), NASA Contractor Report, Clinical Space Medicine, NASA: 23576, Bibcode:1967ntrs.rept23576B, NASA-CR-856, retrieved 2022-12-20.

- ^ Harding, R. M.; Mills, F. J. (April 30, 1983), "Aviation medicine. Problems of altitude I: hypoxia and hyperventilation", British Medical Journal, 286 (6375): 1408–1410, doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6375.1408, PMC 1547870, PMID 6404482.

- ^ Hodkinson, P. D. (March 2011), "Acute exposure to altitude" (PDF), Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 157 (1): 85–91, doi:10.1136/jramc-157-01-15, PMID 21465917, S2CID 43248662, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26, retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ^ Billings 1973, pp. 1–34.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (August 7, 2007), Human Exposure to Vacuum, www.geoffreylandis.com, archived from the original on July 21, 2009, retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Webb, P. (1968), "The Space Activity Suit: An Elastic Leotard for Extravehicular Activity", Aerospace Medicine, 39 (4): 376–383, PMID 4872696.

- ^ Ellery 2000, p. 68.

- ^ Davis, Johnson & Stepanek 2008, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Kanas & Manzey 2008, pp. 15–48.

- ^ Williams, David; et al. (June 23, 2009), "Acclimation during space flight: effects on human physiology", Canadian Medical Association Journal, 180 (13): 1317–1323, doi:10.1503/cmaj.090628, PMC 2696527, PMID 19509005.

- ^ Kennedy, Ann R., Radiation Effects, National Space Biological Research Institute, archived from the original on 2012-01-03, retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ^ Curtis, S. B.; Letaw, J. W. (1989), "Galactic cosmic rays and cell-hit frequencies outside the magnetosphere", Advances in Space Research, 9 (10): 293–298, Bibcode:1989AdSpR...9c.293C, doi:10.1016/0273-1177(89)90452-3, PMID 11537306

- ^ Setlow, Richard B. (November 2003), "The hazards of space travel", Science and Society, 4 (11): 1013–1016, doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400016, PMC 1326386, PMID 14593437.

- ^ Thompson, Andrea (April 9, 2009), Edge of Space Found, space.com, archived from the original on July 14, 2009, retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Sangalli, L.; et al. (2009), "Rocket-based measurements of ion velocity, neutral wind, and electric field in the collisional transition region of the auroral ionosphere", Journal of Geophysical Research, 114 (A4): A04306, Bibcode:2009JGRA..114.4306S, doi:10.1029/2008JA013757.

- ^ a b c Grush, Loren (December 13, 2018), "Why defining the boundary of space may be crucial for the future of spaceflight", The Verge, retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Wong & Fergusson 2010, p. 16.

- ^ FAA Commercial Space Astronaut Wings Program (PDF), Federal Aviation Administration, July 20, 2021, retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ a b Liu, Hao; Tronchetti, Fabio (2019), "Regulating Near-Space Activities: Using the Precedent of the Exclusive Economic Zone as a Model?", Ocean Development & International Law, 50 (2–3): 91–116, doi:10.1080/00908320.2018.1548452.

- ^ a b "Exploring Near Space: Myths, Realities, and Military Implications", CAPS India, April 6, 2024, retrieved 2025-03-11.

- ^ Luo, Wenhui; et al. (November 19, 2024), "Spatial and Temporal Characterization of Near Space Temperature and Humidity and Their Driving Influences", Remote Sensing, 16 (22): 4307, Bibcode:2024RemS...16.4307L, doi:10.3390/rs16224307, ISSN 2072-4292.

- ^ a b c Malinowski, Bartosz (2024), "The Legal Status of Suborbital Aviation Within the International Regulatory Framework for Air and Space Use", Regulatory Dilemmas of Suborbital Flight, Space Regulations Library, vol. 10, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 13–43, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-75087-8_2, ISBN 978-3-031-75086-1.

- ^ a b c McDowell, Jonathan C. (October 2018), "The edge of space: Revisiting the Karman Line", Acta Astronautica, 151: 668–677, arXiv:1807.07894, Bibcode:2018AcAau.151..668M, doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2018.07.003.

- ^ Petty, John Ira (February 13, 2003), "Entry", Human Spaceflight, NASA, archived from the original on October 27, 2011, retrieved 2011-12-16.

- ^ Durrani, Haris (19 July 2019), "Is Spaceflight Colonialism?", The Nation, retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Status of International Agreements relating to activities in outer space as of 1 January 2017 (PDF), United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs/ Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, March 23, 2017, archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2018, retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, January 1, 2008, archived from the original on April 27, 2011, retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ^ Index of Online General Assembly Resolutions Relating to Outer Space, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, 2011, archived from the original on 2010-01-15, retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ^ Wong & Fergusson 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Solanki, Lalit (March 27, 2019), "India Enters the Elite Club: Successfully Shot Down Low Orbit Satellite", The Mirk, archived from the original on 2019-03-28, retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ Columbus launch puts space law to the test, European Science Foundation, November 5, 2007, archived from the original on December 15, 2008, retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ^ Representatives of the States traversed by the Equator (December 3, 1976), "Declaration of the first meeting of equatorial countries", Space Law, Bogota, Republic of Colombia: JAXA, archived from the original on November 24, 2011, retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ Gangale, Thomas (2006), "Who Owns the Geostationary Orbit?", Annals of Air and Space Law, 31, archived from the original on 2011-09-27, retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ "ESIL Reflection – Clearing up the Space Junk – On the Flaws and Potential of International Space Law to Tackle the Space Debris Problem – European Society of International Law", European Society of International Law, March 9, 2023, retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ "Why Don't Satellites Fall Out of the Sky?", National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service, March 11, 2025, retrieved 2025-03-12.

- ^ Hill, James V. H. (April 1999), "Getting to Low Earth Orbit", Space Future, archived from the original on 2012-03-19, retrieved 2012-03-18.

- ^ Shiner, Linda (November 1, 2007), X-15 Walkaround, Air & Space Magazine, retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Williams, David R. (November 17, 2010), "Earth Fact Sheet", Lunar & Planetary Science, NASA, archived from the original on October 30, 2010, retrieved 2012-05-10.

- ^ Dimotakis, P.; et al. (October 1999), 100 lbs to Low Earth Orbit (LEO): Small-Payload Launch Options, The Mitre Corporation, pp. 1–39, archived from the original on 2017-08-29, retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ^ Llop, Josep Virgili; et al. (2014), "Very Low Earth Orbit mission concepts for Earth Observation: Benefits and challenges", Reinventing Space Conference, retrieved 2025-03-09.

- ^ Riebeek, Holli (September 4, 2009), "Catalog of Earth Satellite Orbits", NASA Earth Observatory, retrieved 2025-03-09.

- ^ Ghosh 2000, pp. 47–48.

- ^ "Satellite Drag", NOAA / NWS Space Weather Prediction Center, March 9, 2025, retrieved 2025-03-10.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions, Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science: NASA Orbital Debris Program Office, retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ a b Kennewell, John; McDonald, Andrew (2011), Satellite Lifetimes and Solar Activity, Commonwealth of Australia Bureau of Weather, Space Weather Branch, archived from the original on 2011-12-28, retrieved 2011-12-31.

- ^ Baker, D. N.; et al. (February 2018), "Space Weather Effects in the Earth's Radiation Belts", Space Science Reviews, 214 (1), id. 17, Bibcode:2018SSRv..214...17B, doi:10.1007/s11214-017-0452-7.

- ^ LaForge, L. E.; et al. (2006), Vertical Cavity Surface Emitting Lasers for Spaceflight Multi-Processors, IEEE, pp. 1–19, doi:10.1109/AERO.2006.1655895, ISBN 978-0-7803-9545-9.

- ^ Baker, D. N.; et al. (2018), "Space Weather Effects in the Earth's Radiation Belts" (PDF), Space Science Reviews, 214 (1) 17, Bibcode:2018SSRv..214...17B, doi:10.1007/s11214-017-0452-7, ISSN 0038-6308, retrieved 2025-03-10.

- ^ "Earth's Magnetosphere, Electrons & Protons", Encyclopedia Britannica, February 24, 2025, retrieved 2025-03-10.

- ^ Ali, Irfan; et al. (2002), "Little LEO Satellites", Doppler Applications in LEO Satellite Communication Systems, The Springer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 656, pp. 1–26, doi:10.1007/0-306-47546-4_1, ISBN 0-7923-7616-1, retrieved 2025-03-09.

- ^ Koteskey, Tyler (November 5, 2024), "Nuclear Detonations in Space: Reducing Risks to Low Earth Orbit Satellites", Georgetown Security Studies Review, retrieved 2025-03-09,

The inner Van Allen belt overlaps with the upper edge of low-earth orbit

- ^ Kovar, Pavel; et al. (December 2020), "Measurement of cosmic radiation in LEO by 1U CubeSat☆", Radiation Measurements, 139 106471, Bibcode:2020RadM..13906471K, doi:10.1016/j.radmeas.2020.106471,

The radiation field in low Earth orbit (LEO) comprises a third radiation source, the Van Allen radiation belts...

- ^ Catling, David C.; Kasting, James F. (2017), Atmospheric Evolution on Inhabited and Lifeless Worlds, Cambridge University Press, p. 4, Bibcode:2017aeil.book.....C, ISBN 9781316824528.

- ^ a b c "42 USC 18302: Definitions", uscode.house.gov (in Kinyarwanda), December 15, 2022, retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Schrijver & Siscoe 2010, p. 363, 379.

- ^ a b Howell, Elizabeth (April 24, 2015), "What Is a Geosynchronous Orbit?", Space.com, retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b Strickland, John K. (October 1, 2012), The cislunar gateway with no gate, The Space Review, archived from the original on February 7, 2016, retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ Portree, David; Loftus, Joseph (1999), "Orbital Debris: A Chronology" (PDF), NASA Sti/Recon Technical Report N, 99, NASA: 13, Bibcode:1999STIN...9941786P, archived from the original (PDF) on 2000-09-01, retrieved 2012-05-05.

- ^ Photo Gallery, ARES | NASA Orbital Debris Program Office, retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ Kintner, Paul; GMDT Committee and Staff (September 2002), Report of the Living With a Star Geospace Mission Definition Team (PDF), NASA, archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-02, retrieved 2012-04-15.

- ^ Schrijver & Siscoe 2010, p. 379.

- ^ Fichtner & Liu 2011, pp. 341–345.

- ^ Koskinen 2010, pp. 32, 42.

- ^ Hones, Edward W. Jr. (March 1986), "The Earth's Magnetotail", Scientific American, 254 (3): 40–47, Bibcode:1986SciAm.254c..40H, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0386-40, JSTOR 24975910

- ^ Mendillo 2000, p. 275.

- ^ Goodman 2006, p. 244.

- ^ "Geomagnetic Storms" (PDF), OECD/IFP Futures Project on "Future Global Shocks", CENTRA Technology, Inc., pp. 1–69, January 14, 2011, archived (PDF) from the original on March 14, 2012, retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ Cunio, P. M.; et al. (2021), "Utilization potential for distinct orbit families in the cislunar domain", Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference (AMOS), Maui, HI, USA: Maui Economic Development Board (PDF), retrieved 2025-03-09.

- ^ "Why We Explore", NASA, June 13, 2013, retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Yoder, Charles F. (1995), "Astrometric and Geodetic Properties of Earth and the Solar System", in Ahrens, Thomas J. (ed.), Global earth physics a handbook of physical constants (PDF), AGU reference shelf Series, vol. 1, Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union, p. 1, Bibcode:1995geph.conf....1Y, ISBN 978-0-87590-851-9, archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2012, retrieved 2011-12-31.. This work lists a Hill sphere radius of 234.9 times the mean radius of Earth, or 234.9 km × 6371 km = 1.5 million km.

- ^ Barbieri 2006, p. 253.

- ^ Granvik, Mikael; et al. (March 2012), "The population of natural Earth satellites", Icarus, 218 (1): 262–277, arXiv:1112.3781, Bibcode:2012Icar..218..262G, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.12.003.

- ^ "51 U.S.C 10101 -National and Commercial Space Programs, Subtitle I-General, Chapter 101-Definitions", United States Code, Office of Law Revision Council, U. S. House of Representatives, retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Dickson 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Williamson 2006, p. 97.

- ^ "Definition of 'deep space'", Collins English Dictionary, retrieved 2018-01-15.

- ^ ITU-R Radio Regulations, Article 1, Terms and definitions, Section VIII, Technical terms relating to space, paragraph 1.177. (PDF), International Telecommunication Union, retrieved 2018-02-05,

1.177 deep space: Space at distances from the Earth equal to, or greater than, 2×106 km

- ^ The semi-major axis of the Moon's orbit is 384,400 km, which is 19.2% of two million km, or about one-fifth.

Williams, David R. (December 20, 2021), Moon Fact Sheet, NASA, archived from the original on 2019-04-02, retrieved 2023-09-23. - ^ "Interplanetary trajectories", ESA, retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ^ a b Cessna, Abby (July 5, 2009), "Interplanetary space", Universe Today, archived from the original on March 19, 2015.

- ^ Kohler, Susanna (December 1, 2017), "A Shifting Shield Provides Protection Against Cosmic Rays", Nova, American Astronomical Society, p. 2992, Bibcode:2017nova.pres.2992K, retrieved 2019-01-31.

- ^ Phillips, Tony (September 29, 2009), Cosmic Rays Hit Space Age High, NASA, archived from the original on 2009-10-14, retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ a b Papagiannis 1972, pp. 12–149.

- ^ NASA (March 12, 2019), "What scientists found after sifting through dust in the solar system", EurekAlert!, archived from the original on 26 May 2020, retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Flynn, G. J.; et al. (2003), "The Origin of Organic Matter in the Solar System: Evidence from the Interplanetary Dust Particles", in Norris, R.; Stootman, F. (eds.), Bioastronomy 2002: Life Among the Stars, Proceedings of IAU Symposium No. 213, vol. 213, p. 275, Bibcode:2004IAUS..213..275F.

- ^ Leinert, C.; Grun, E. (1990), "Interplanetary Dust", Physics of the Inner Heliosphere I, p. 207, Bibcode:1990pihl.book..207L, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-75361-9_5, ISBN 978-3-642-75363-3.

- ^ Johnson, R. E. (August 1994), "Plasma-Induced Sputtering of an Atmosphere", Space Science Reviews, 69 (3–4): 215–253, Bibcode:1994SSRv...69..215J, doi:10.1007/BF02101697, S2CID 121800711.

- ^ Cook, Jia-Rui (September 12, 2013), "How do we know when Voyager reaches interstellar space?", JPL News, 2013-278, archived from the original on September 15, 2013.

- ^ Cooper, Keith (January 17, 2023), "Interstellar space: What is it and where does it begin?", Space.com, retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ Garcia-Sage, K.; et al. (February 2023), "Star-Exoplanet Interactions: A Growing Interdisciplinary Field in Heliophysics", Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, 10 1064076, id. 25, Bibcode:2023FrASS..1064076G, doi:10.3389/fspas.2023.1064076.

- ^ a b Ferrière, Katia M. (2001), "The interstellar environment of our galaxy", Reviews of Modern Physics, 73 (4): 1031–1066, arXiv:astro-ph/0106359, Bibcode:2001RvMP...73.1031F, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.73.1031, S2CID 16232084.

- ^ Witt, Adolf N. (October 2001), "The Chemical Composition of the Interstellar Medium", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences – Origin and early evolution of solid matter in the Solar System, vol. 359, p. 1949, Bibcode:2001RSPTA.359.1949W, doi:10.1098/rsta.2001.0889, S2CID 91378510.

- ^ Boulares, Ahmed; Cox, Donald P. (December 1990), "Galactic hydrostatic equilibrium with magnetic tension and cosmic-ray diffusion", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 365: 544–558, Bibcode:1990ApJ...365..544B, doi:10.1086/169509.

- ^ Rauchfuss 2008, pp. 72–81.

- ^ Klemperer, William (August 15, 2006), "Interstellar chemistry", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103 (33): 12232–12234, Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312232K, doi:10.1073/pnas.0605352103, PMC 1567863, PMID 16894148.

- ^ Redfield, S. (September 2006), "The Local Interstellar Medium", New Horizons in Astronomy; Proceedings of the Conference Held 16–18 October 2005 at The University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA, Frank N. Bash Symposium ASP Conference Series, vol. 352, p. 79, arXiv:astro-ph/0601117, Bibcode:2006ASPC..352...79R.

- ^ McComas, D. J.; et al. (2012), "The Heliosphere's Interstellar Interaction: No Bow Shock", Science, 336 (6086): 1291–3, Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1291M, doi:10.1126/science.1221054, PMID 22582011, S2CID 206540880.

- ^ a b Fox, Karen C. (May 10, 2012), NASA – IBEX Reveals a Missing Boundary at the Edge of the Solar System, NASA, archived from the original on May 12, 2012, retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ^ Wszolek 2013, p. 67.

- ^ Jafelice, Luiz C.; Opher, Reuven (July 1992), "The origin of intergalactic magnetic fields due to extragalactic jets", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 257 (1): 135–151, Bibcode:1992MNRAS.257..135J, doi:10.1093/mnras/257.1.135.

- ^ Wadsley, James W.; et al. (August 20, 2002), "The Universe in Hot Gas", Astronomy Picture of the Day, NASA, archived from the original on June 9, 2009, retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ "Intergalactic medium", Harvard & Smithsonian, June 16, 2022, retrieved 2024-04-16.

- ^ a b Fang, T.; et al. (2010), "Confirmation of X-Ray Absorption by Warm-Hot Intergalactic Medium in the Sculptor Wall", The Astrophysical Journal, 714 (2): 1715, arXiv:1001.3692, Bibcode:2010ApJ...714.1715F, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/714/2/1715, S2CID 17524108.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Benjamin D.; Davé, Romeel (December 2006), "Cosmological simulations of intergalactic medium enrichment from galactic outflows", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 373 (4): 1265–1292, arXiv:astro-ph/0605651, Bibcode:2006MNRAS.373.1265O, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10989.x.

- ^ Bykov, A. M.; et al. (February 2008), "Equilibration Processes in the Warm-Hot Intergalactic Medium", Space Science Reviews, 134 (1–4): 141–153, arXiv:0801.1008, Bibcode:2008SSRv..134..141B, doi:10.1007/s11214-008-9309-4, S2CID 17801881.

- ^ Wakker, B. P.; Savage, B. D. (2009), "The Relationship Between Intergalactic H I/O VI and Nearby (z<0.017) Galaxies", The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 182 (1): 378, arXiv:0903.2259, Bibcode:2009ApJS..182..378W, doi:10.1088/0067-0049/182/1/378, S2CID 119247429.

- ^ Mathiesen, B. F.; Evrard, A. E. (2001), "Four Measures of the Intracluster Medium Temperature and Their Relation to a Cluster's Dynamical State", The Astrophysical Journal, 546 (1): 100, arXiv:astro-ph/0004309, Bibcode:2001ApJ...546..100M, doi:10.1086/318249, S2CID 17196808.

- ^ Grant 1981, p. 10.

- ^ Porter, Park & Daston 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Eckert 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Needham & Ronan 1985, pp. 82–87.

- ^ West, John B. (March 2013), "Torricelli and the Ocean of Air: The First Measurement of Barometric Pressure", Physiology (Bethesda), 28 (2): 66–73, doi:10.1152/physiol.00053.2012, PMC 3768090, PMID 23455767.

- ^ Holton & Brush 2001, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Cajori 1917, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Genz 2001, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Tassoul & Tassoul 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Gatti 2002, pp. 99–104.

- ^ Kelly 1965, pp. 97–107.

- ^ Olenick, Apostol & Goodstein 1986, p. 356.

- ^ Hariharan 2003, p. 2.