Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Condorcet method

View on Wikipedia| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

A Condorcet method (English: /kɒndɔːrˈseɪ/; French: [kɔ̃dɔʁsɛ]) is an election method that elects the candidate who wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidates, whenever there is such a candidate. A candidate with this property, the pairwise champion or beats-all winner, is formally called the Condorcet winner[1] or Pairwise Majority Rule Winner (PMRW).[2][3] The head-to-head elections need not be done separately; a voter's choice within any given pair can be determined from the ranking.[4][5]

Some elections may not yield a Condorcet winner because voter preferences may be cyclic—that is, it is possible that every candidate has an opponent that defeats them in a two-candidate contest.[6] The possibility of such cyclic preferences is known as the Condorcet paradox. However, a smallest group of candidates that beat all candidates not in the group, known as the Smith set, always exists. The Smith set is guaranteed to have the Condorcet winner in it should one exist. Many Condorcet methods elect a candidate who is in the Smith set absent a Condorcet winner, and are thus said to be "Smith-efficient".[7]

Condorcet voting methods are named for the 18th-century French mathematician and philosopher Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas Caritat, the Marquis de Condorcet, who championed such systems. However, Ramon Llull devised the earliest known Condorcet method in 1299.[8] It was equivalent to Copeland's method in cases with no pairwise ties.[9]

Condorcet methods may use preferential ranked, rated vote ballots, or explicit votes between all pairs of candidates. Most Condorcet methods employ a single round of preferential voting, in which each voter ranks the candidates from most (marked as number 1) to least preferred (marked with a higher number). A voter's ranking is often called their order of preference. Votes can be tallied in many ways to find a winner. All Condorcet methods will elect the Condorcet winner if there is one. If there is no Condorcet winner different Condorcet-compliant methods may elect different winners in the case of a cycle—Condorcet methods differ on which other criteria they satisfy.

The procedure given in Robert's Rules of Order for voting on motions and amendments is also a Condorcet method, even though the voters do not vote by expressing their orders of preference.[10] There are multiple rounds of voting, and in each round the vote is between two of the alternatives. The loser (by majority rule) of a pairing is eliminated, and the winner of a pairing survives to be paired in a later round against another alternative. Eventually, only one alternative remains, and it is the winner. This is analogous to a single-winner or round-robin tournament; the total number of pairings is one less than the number of alternatives. Since a Condorcet winner will win by majority rule in each of its pairings, it will never be eliminated by Robert's Rules. But this method cannot reveal a voting paradox in which there is no Condorcet winner and a majority prefer an early loser over the eventual winner (though it will always elect someone in the Smith set). A considerable portion of the literature on social choice theory is about the properties of this method since it is widely used and is used by important organizations (legislatures, councils, committees, etc.). It is not practical for use in public elections, however, since its multiple rounds of voting would be very expensive for voters, for candidates, and for governments to administer.

Condorcet methods are recommended by the Equal Vote Coalition under the name Ranked Robin.[11][12]

Summary

[edit]In a contest between candidates A, B and C using the preferential-vote form of Condorcet method, a head-to-head race is conducted between each pair of candidates. A and B, B and C, and C and A. If one candidate is preferred over all others, they are the Condorcet Winner and winner of the election.

Because of the possibility of the Condorcet paradox, it is possible, but unlikely,[13] that a Condorcet winner may not exist in a specific election. This is sometimes called a Condorcet cycle or just cycle and can be thought of as Rock beating Scissors, Scissors beating Paper, and Paper beating Rock. Various Condorcet methods differ in how they resolve such a cycle. (Most elections do not have cycles. See Condorcet paradox#Likelihood for estimates.) If there is no cycle, all Condorcet methods elect the same candidate and are operationally equivalent.

- Each voter ranks the candidates in order of preference (top-to-bottom, or best-to-worst, or 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.). The voter may be allowed to rank candidates as equals and to express indifference (no preference) between them. Candidates omitted by a voter may be treated as if the voter ranked them at the bottom.[14]

- For each pairing of candidates (as in a round-robin tournament) count how many votes rank each candidate over the other candidate. Thus each pairing will have two totals: the size of its majority and the size of its minority[citation needed][15] (or there will be a tie).

For most Condorcet methods, those counts usually suffice to determine the complete order of finish (i.e. who won, who came in 2nd place, etc.). They always suffice to determine whether there is a Condorcet winner.

Additional information may be needed in the event of ties. Ties can be pairings that have no majority, or they can be majorities that are the same size. Such ties will be rare when there are many voters. Some Condorcet methods may have other kinds of ties. For example, with Copeland's method, it would not be rare for two or more candidates to win the same number of pairings, when there is no Condorcet winner.[citation needed]

Definition

[edit]A Condorcet method is a voting system that will always elect the Condorcet winner (if there is one); this is the candidate whom voters prefer to each other candidate, when compared to them one at a time. This candidate can be found (if they exist; see next paragraph) by checking if there is a candidate who beats all other candidates; this can be done by using Copeland's method and then checking if the Copeland winner has the highest possible Copeland score. They can also be found by conducting a series of pairwise comparisons, using the procedure given in Robert's Rules of Order described above. For N candidates, this requires N − 1 pairwise hypothetical elections. For example, with 5 candidates there are 4 pairwise comparisons to be made, since after each comparison, a candidate is eliminated, and after 4 eliminations, only one of the original 5 candidates will remain.

To confirm that a Condorcet winner exists in a given election, first do the Robert's Rules of Order procedure, declare the final remaining candidate the procedure's winner, and then do at most an additional N − 2 pairwise comparisons between the procedure's winner and any candidates they have not been compared against yet (including all previously eliminated candidates). If the procedure's winner does not win all pairwise matchups, then no Condorcet winner exists in the election (and thus the Smith set has multiple candidates in it).

Computing all pairwise comparisons requires ½N(N−1) pairwise comparisons for N candidates. For 10 candidates, this means 0.5*10*9=45 comparisons, which can make elections with many candidates hard to count the votes for.[citation needed]

The family of Condorcet methods is also referred to collectively as Condorcet's method. A voting system that always elects the Condorcet winner when there is one is described by electoral scientists as a system that satisfies the Condorcet criterion.[16] Additionally, a voting system can be considered to have Condorcet consistency, or be Condorcet consistent, if it elects any Condorcet winner.[17]

In certain circumstances, an election has no Condorcet winner. This occurs as a result of a kind of tie known as a majority rule cycle, described by Condorcet's paradox. The manner in which a winner is then chosen varies from one Condorcet method to another. Some Condorcet methods involve the basic procedure described below, coupled with a Condorcet completion method, which is used to find a winner when there is no Condorcet winner. Other Condorcet methods involve an entirely different system of counting, but are classified as Condorcet methods, or Condorcet consistent, because they will still elect the Condorcet winner if there is one.[17]

Not all single winner, ranked voting systems are Condorcet methods. For example, instant-runoff voting and the Borda count are not Condorcet methods.[17][18]

Basic procedure

[edit]Voting

[edit]In a Condorcet election the voter ranks the list of candidates in order of preference. If a ranked ballot is used, the voter gives a "1" to their first preference, a "2" to their second preference, and so on. Some Condorcet methods allow voters to rank more than one candidate equally so that the voter might express two first preferences rather than just one.[19] If a scored ballot is used, voters rate or score the candidates on a scale, for example as is used in Score voting, with a higher rating indicating a greater preference.[20] When a voter does not give a full list of preferences, it is typically assumed that they prefer the candidates that they have ranked over all the candidates that were not ranked, and that there is no preference between candidates that were left unranked. Some Condorcet elections permit write-in candidates.

Finding the winner

[edit]The count is conducted by pitting every candidate against every other candidate in a series of hypothetical one-on-one contests. The winner of each pairing is the candidate preferred by a majority of voters. Unless they tie, there is always a majority when there are only two choices. The candidate preferred by each voter is taken to be the one in the pair that the voter ranks (or rates) higher on their ballot paper. For example, if Alice is paired against Bob it is necessary to count both the number of voters who have ranked Alice higher than Bob, and the number who have ranked Bob higher than Alice. If Alice is preferred by more voters then she is the winner of that pairing. When all possible pairings of candidates have been considered, if one candidate beats every other candidate in these contests then they are declared the Condorcet winner. As noted above, if there is no Condorcet winner a further method must be used to find the winner of the election, and this mechanism varies from one Condorcet consistent method to another.[17] In any Condorcet method that passes Independence of Smith-dominated alternatives, it can sometimes help to identify the Smith set from the head-to-head matchups, and eliminate all candidates not in the set before doing the procedure for that Condorcet method.

Pairwise counting and matrices

[edit]Condorcet methods use pairwise counting. For each possible pair of candidates, one pairwise count indicates how many voters prefer one of the paired candidates over the other candidate, and another pairwise count indicates how many voters have the opposite preference. The counts for all possible pairs of candidates summarize all the pairwise preferences of all the voters.

Pairwise counts are often displayed in a pairwise comparison matrix,[21] or outranking matrix,[22] such as those below. In these matrices, each row represents each candidate as a 'runner', while each column represents each candidate as an 'opponent'. The cells at the intersection of rows and columns each show the result of a particular pairwise comparison. Cells comparing a candidate to themselves are left blank.[23][24]

Imagine there is an election between four candidates: A, B, C, and D. The first matrix below records the preferences expressed on a single ballot paper, in which the voter's preferences are (B, C, A, D); that is, the voter ranked B first, C second, A third, and D fourth. In the matrix a '1' indicates that the runner is preferred over the 'opponent', while a '0' indicates that the runner is defeated.[23][21]

Opponent Runner |

A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | — | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| B | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | |

| C | 1 | 0 | — | 1 | |

| D | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | |

| A '1' indicates that the runner is preferred over the opponent; a '0' indicates that the runner is defeated. | |||||

Using a matrix like the one above, one can find the overall results of an election. Each ballot can be transformed into this style of matrix, and then added to all other ballot matrices using matrix addition. The sum of all ballots in an election is called the sum matrix. Suppose that in the imaginary election there are two other voters. Their preferences are (D, A, C, B) and (A, C, B, D). Added to the first voter, these ballots would give the following sum matrix:

Opponent Runner |

A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | — | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| B | 1 | — | 1 | 2 |

| C | 1 | 2 | — | 2 |

| D | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

When the sum matrix is found, the contest between each pair of candidates is considered. The number of votes for runner over opponent (runner, opponent) is compared with the number of votes for opponent over runner (opponent, runner) to find the Condorcet winner. In the sum matrix above, A is the Condorcet winner because A beats every other candidate. When there is no Condorcet winner Condorcet completion methods, such as Ranked Pairs and the Schulze method, use the information contained in the sum matrix to choose a winner.

Cells marked '—' in the matrices above have a numerical value of '0', but a dash is used since candidates are never preferred to themselves. The first matrix, that represents a single ballot, is inversely symmetric: (runner, opponent) is ¬(opponent, runner). Or (runner, opponent) + (opponent, runner) = 1. The sum matrix has this property: (runner, opponent) + (opponent, runner) = N for N voters, if all runners were fully ranked by each voter.

Example

[edit]

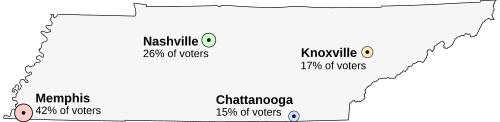

| 42% of voters |

26% of voters |

15% of voters |

17% of voters |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Suppose Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is split between four cities, and all the voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, large but far to the west

- Nashville, medium, near the center

- Chattanooga, small and in the east

- Knoxville, small and isolated

To find the Condorcet winner every candidate must be matched against every other candidate in a series of imaginary one-on-one contests. In each pairing the winner is the candidate preferred by a majority of voters. When results for every possible pairing have been found they are as follows:

| Pair | Winner |

|---|---|

| Memphis (42%) vs. Nashville (58%) | Nashville |

| Memphis (42%) vs. Chattanooga (58%) | Chattanooga |

| Memphis (42%) vs. Knoxville (58%) | Knoxville |

| Nashville (68%) vs. Chattanooga (32%) | Nashville |

| Nashville (68%) vs. Knoxville (32%) | Nashville |

| Chattanooga (83%) vs. Knoxville (17%) | Chattanooga |

The results can also be shown in the form of a matrix:

| 1st | Nashville [N] | 3 Wins ↓ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd | Chattanooga [C] | → 1 Loss ↓ 2 Wins

|

[N] 68% [C] 32% | ||

| 3rd | Knoxville [K] | → 2 Losses ↓ 1 Win

|

[C] 83% [K] 17% |

[N] 68% [K] 32% | |

| 4th | Memphis [M] | 3 Losses → | [K] 58% [M] 42% |

[C] 58% [M] 42% |

[N] 58% [M] 42% |

As can be seen from both of the tables above, Nashville beats every other candidate. This means that Nashville is the Condorcet winner. Nashville will thus win an election held under any possible Condorcet method.

While any Condorcet method will elect Nashville as the winner, if instead an election based on the same votes were held using first-past-the-post or instant-runoff voting, these systems would select Memphis[footnotes 1] and Knoxville[footnotes 2] respectively. This would occur despite the fact that most people would have preferred Nashville to either of those "winners". Condorcet methods make these preferences obvious rather than ignoring or discarding them.

On the other hand, in this example Chattanooga also defeats Knoxville and Memphis when paired against those cities. If we changed the basis for defining preference and determined that Memphis voters preferred Chattanooga as a second choice rather than as a third choice, Chattanooga would be the Condorcet winner even though finishing in last place in a first-past-the-post election.

An alternative way of thinking about this example if a Smith-efficient Condorcet method that passes ISDA is used to determine the winner is that 58% of the voters, a mutual majority, ranked Memphis last (making Memphis the majority loser) and Nashville, Chattanooga, and Knoxville above Memphis, ruling Memphis out. At that point, the voters who preferred Memphis as their 1st choice could only help to choose a winner among Nashville, Chattanooga, and Knoxville, and because they all preferred Nashville as their 1st choice among those three, Nashville would have had a 68% majority of 1st choices among the remaining candidates and won as the majority's 1st choice.

Circular ambiguities

[edit]As noted above, sometimes an election has no Condorcet winner because there is no candidate who is preferred by voters to all other candidates. When this occurs the situation is known as a 'Condorcet cycle', 'majority rule cycle', 'circular ambiguity', 'circular tie', 'Condorcet paradox', or simply a 'cycle'. This situation emerges when, once all votes have been tallied, the preferences of voters with respect to some candidates form a circle in which every candidate is beaten by at least one other candidate (Intransitivity).

For example, if there are three candidates, Candidate Rock, Candidate Scissors, and Candidate Paper, there will be no Condorcet winner if voters prefer Candidate Rock over Candidate Scissors and Scissors over Paper, but also Candidate Paper over Rock. Depending on the context in which elections are held, circular ambiguities may or may not be common, but there is no known case of a governmental election with ranked-choice voting in which a circular ambiguity is evident from the record of ranked ballots. Nonetheless, a cycle is always possible, and so every Condorcet method should be capable of determining a winner when this contingency occurs. A mechanism for resolving an ambiguity is known as ambiguity resolution, cycle resolution method, or Condorcet completion method.

Circular ambiguities arise as a result of the voting paradox—the result of an election can be intransitive (forming a cycle) even though all individual voters expressed a transitive preference. In a Condorcet election it is impossible for the preferences of a single voter to be cyclical, because a voter must rank all candidates in order, from top-choice to bottom-choice, and can only rank each candidate once, but the paradox of voting means that it is still possible for a circular ambiguity in voter tallies to emerge.

The idealized notion of a political spectrum is often used to describe political candidates and policies. Where this kind of spectrum exists, and voters prefer candidates who are closest to their own position on the spectrum, there is a Condorcet winner (Black's Single-Peakedness Theorem).

In Condorcet methods, as in most electoral systems, there is also the possibility of an ordinary tie. This occurs when two or more candidates tie with each other but defeat every other candidate. As in other systems this can be resolved by a random method such as the drawing of lots. Ties can also be settled through other methods like seeing which of the tied winners had the most first choice votes, but this and some other non-random methods may re-introduce a degree of tactical voting, especially if voters know the race will be close.

The method used to resolve circular ambiguities is the main difference between the various Condorcet methods. There are countless ways in which this can be done, but every Condorcet method involves ignoring the majorities expressed by voters in at least some pairwise matchings. Some cycle resolution methods are Smith-efficient, meaning that they pass the Smith criterion. This guarantees that when there is a cycle (and no pairwise ties), only the candidates in the cycle can win, and that if there is a mutual majority, one of their preferred candidates will win.

Condorcet methods fit within two categories:

- Two-method systems, which use a separate method to handle cases in which there is no Condorcet winner

- One-method systems, which use a single method that, without any special handling, always identifies the winner to be the Condorcet winner

Many one-method systems and some two-method systems will give the same result as each other if there are fewer than 4 candidates in the circular tie, and all voters separately rank at least two of those candidates. These include Smith-Minimax (Minimax but done only after all candidates not in the Smith set are eliminated), Ranked Pairs, and Schulze. For example, with three candidates in the Smith set in a Condorcet cycle, because Schulze and Ranked Pairs pass ISDA, all candidates not in the Smith set can be eliminated first, and then for Schulze, dropping the weakest defeat of the three allows the candidate who had that weakest defeat to be the only candidate who can beat or tie all other candidates, while with Ranked Pairs, once the first two strongest defeats are locked in, the weakest cannot, since it'd create a cycle, and so the candidate with the weakest defeat will have no defeats locked in against them).

Two-method systems

[edit]One family of Condorcet methods consists of systems that first conduct a series of pairwise comparisons and then, if there is no Condorcet winner, fall back to an entirely different, non-Condorcet method to determine a winner. The simplest such fall-back methods involve entirely disregarding the results of the pairwise comparisons. For example, the Black method chooses the Condorcet winner if it exists, but uses the Borda count instead if there is a cycle (the method is named for Duncan Black).

A more sophisticated two-stage process is, in the event of a cycle, to use a separate voting system to find the winner but to restrict this second stage to a certain subset of candidates found by scrutinizing the results of the pairwise comparisons. Sets used for this purpose are defined so that they will always contain only the Condorcet winner if there is one, and will always, in any case, contain at least one candidate. Such sets include the

- Smith set: The smallest non-empty set of candidates in a particular election such that every candidate in the set can beat all candidates outside the set. It is easily shown that there is only one possible Smith set for each election.

- Schwartz set: This is the innermost unbeaten set, and is usually the same as the Smith set. It is defined as the union of all possible sets of candidates such that for every set:

- Every candidate inside the set is pairwise unbeatable by any other candidate outside the set (i.e., ties are allowed).

- No proper (smaller) subset of the set fulfills the first property.

- Landau set or uncovered set or Fishburn set: the set of candidates, such that each member, for every other candidate (including those inside the set), either beats this candidate or beats a third candidate that itself beats the candidate that is unbeaten by the member.

One possible method is to apply instant-runoff voting in various ways, such as to the candidates of the Smith set. One variation of this method has been described as "Smith/IRV", with another being Tideman's alternative methods. It is also possible to do "Smith/Approval" by allowing voters to rank candidates, and indicate which candidates they approve, such that the candidate in the Smith set approved by the most voters wins; this is often done using an approval threshold (i.e. if voters approve their 3rd choices, those voters are automatically considered to approve their 1st and 2nd choices too). In Smith/Score, the candidate in the Smith set with the highest total score wins, with the pairwise comparisons done based on which candidates are scored higher than others.

Single-method systems

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

Some Condorcet methods use a single procedure that inherently meets the Condorcet criteria and, without any extra procedure, also resolves circular ambiguities when they arise. In other words, these methods do not involve separate procedures for different situations. Typically these methods base their calculations on pairwise counts. These methods include:

- Copeland's method: This simple method involves electing the candidate who wins the most pairwise matchings. However, it often produces a tie.

- Kemeny method: This method ranks all the choices from most popular and second-most popular down to least popular.

- Minimax: Also called Simpson, Simpson–Kramer, and Simple Condorcet, this method chooses the candidate whose worst pairwise defeat is better than that of all other candidates. A refinement of this method involves restricting it to choosing a winner from among the Smith set; this has been called Smith/Minimax.

- Nanson's method and Baldwin's method combine Borda Count with an instant runoff procedure.

- Dodgson's method extends the Condorcet method by swapping candidates until a Condorcet winner is found. The winner is the candidate which requires the minimum number of swaps.

- Ranked pairs breaks each cycle in the pairwise preference graph by dropping the weakest majority in the cycle, thereby yielding a complete ranking of the candidates. This method is also known as Tideman, after its inventor Nicolaus Tideman.

- Schulze method iteratively drops the weakest majority in the pairwise preference graph until the winner becomes well defined. This method is also known as Schwartz sequential dropping (SSD), cloneproof Schwartz sequential dropping (CSSD), beatpath method, beatpath winner, path voting, and path winner.

- Smith Score is a rated voting method which elects the Score voting winner from the Smith set.[25]

Ranked Pairs and Schulze are procedurally in some sense opposite approaches (although they very frequently give the same results):

- Ranked Pairs (and its variants) starts with the strongest defeats and uses as much information as it can without creating ambiguity.

- Schulze repeatedly removes the weakest defeat until the ambiguity is removed.

Minimax could be considered as more "blunt" than either of these approaches, as instead of removing defeats it can be seen as immediately removing candidates by looking at the strongest defeats (although their victories are still considered for subsequent candidate eliminations). One way to think of it in terms of removing defeats is that Minimax removes each candidate's weakest defeats until some group of candidates with only pairwise ties between them have no defeats left, at which point the group ties to win.[citation needed]

Kemeny method

[edit]The Kemeny method considers every possible sequence of choices in terms of which choice might be most popular, which choice might be second-most popular, and so on down to which choice might be least popular. Each such sequence is associated with a Kemeny score that is equal to the sum of the pairwise counts that apply to the specified sequence. The sequence with the highest score is identified as the overall ranking, from most popular to least popular.

When the pairwise counts are arranged in a matrix in which the choices appear in sequence from most popular (top and left) to least popular (bottom and right), the winning Kemeny score equals the sum of the counts in the upper-right, triangular half of the matrix (shown here in bold on a green background).

| ...over Nashville | ...over Chattanooga | ...over Knoxville | ...over Memphis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefer Nashville... | — | 68 | 68 | 58 |

| Prefer Chattanooga... | 32 | — | 83 | 58 |

| Prefer Knoxville... | 32 | 17 | — | 58 |

| Prefer Memphis... | 42 | 42 | 42 | — |

In this example, the Kemeny Score of the sequence Nashville > Chattanooga > Knoxville > Memphis would be 393.

Calculating every Kemeny score requires considerable computation time in cases that involve more than a few choices. However, fast calculation methods based on integer programming allow a computation time in seconds for some cases with as many as 40 choices.

Ranked pairs

[edit]The order of finish is constructed a piece at a time by considering the (pairwise) majorities one at a time, from largest majority to smallest majority. For each majority, their higher-ranked candidate is placed ahead of their lower-ranked candidate in the (partially constructed) order of finish, except when their lower-ranked candidate has already been placed ahead of their higher-ranked candidate.

For example, suppose the voters' orders of preference are such that 75% rank B over C, 65% rank A over B, and 60% rank C over A. (The three majorities are a rock paper scissors cycle.) Ranked pairs begins with the largest majority, who rank B over C, and places B ahead of C in the order of finish. Then it considers the second largest majority, who rank A over B, and places A ahead of B in the order of finish. At this point, it has been established that A finishes ahead of B and B finishes ahead of C, which implies A also finishes ahead of C. So when ranked pairs considers the third largest majority, who rank C over A, their lower-ranked candidate A has already been placed ahead of their higher-ranked candidate C, so C is not placed ahead of A. The order of finish is "A, B, C" and A is the winner.

An equivalent definition is to find the order of finish that minimizes the size of the largest reversed majority. (In the 'lexicographical order' sense. If the largest majority reversed in two orders of finish is the same, the two orders of finish are compared by their second largest reversed majorities, etc. See the discussion of MinMax, MinLexMax and Ranked Pairs in the 'Motivation and uses' section of the Lexicographical Order article). (In the example, the order of finish "A, B, C" reverses the 60% who rank C over A. Any other order of finish would reverse a larger majority.) This definition is useful for simplifying some of the proofs of Ranked Pairs' properties, but the "constructive" definition executes much faster (small polynomial time).

Schulze method

[edit]The Schulze method resolves votes as follows:

- At each stage, we proceed as follows:

- For each pair of undropped candidates X and Y: If there is a directed path of undropped links from candidate X to candidate Y, then we write "X → Y"; otherwise we write "not X → Y".

- For each pair of undropped candidates V and W: If "V → W" and "not W → V", then candidate W is dropped and all links, that start or end in candidate W, are dropped.

- The weakest undropped link is dropped. If several undropped links tie as weakest, all of them are dropped.

- The procedure ends when all links have been dropped. The winners are the undropped candidates.

In other words, this procedure repeatedly throws away the weakest pairwise defeat within the top set, until finally the number of votes left over produce an unambiguous decision.

Defeat strength

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

Some pairwise methods—including minimax, Ranked Pairs, and the Schulze method—resolve circular ambiguities based on the relative strength of the defeats. There are different ways to measure the strength of each defeat, and these include considering "winning votes" and "margins":

- Winning votes: The number of votes on the winning side of a defeat.

- Margins: The number of votes on the winning side of the defeat, minus the number of votes on the losing side of the defeat.[26]

If voters do not rank their preferences for all of the candidates, these two approaches can yield different results. Consider, for example, the following election:

| 45 voters | 11 voters | 15 voters | 29 voters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. C | 2. B |

The pairwise defeats are as follows:

- B beats A, 55 to 45 (55 winning votes, a margin of 10 votes)

- A beats C, 45 to 44 (45 winning votes, a margin of 1 vote)

- C beats B, 29 to 26 (29 winning votes, a margin of 3 votes)

Using the winning votes definition of defeat strength, the defeat of B by C is the weakest, and the defeat of A by B is the strongest. Using the margins definition of defeat strength, the defeat of C by A is the weakest, and the defeat of A by B is the strongest.

Using winning votes as the definition of defeat strength, candidate B would win under minimax, Ranked Pairs and the Schulze method, but, using margins as the definition of defeat strength, candidate C would win in the same methods.

If all voters give complete rankings of the candidates, then winning votes and margins will always produce the same result. The difference between them can only come into play when some voters declare equal preferences amongst candidates, as occurs implicitly if they do not rank all candidates, as in the example above.

The choice between margins and winning votes is the subject of scholarly debate. Because all Condorcet methods always choose the Condorcet winner when one exists, the difference between methods only appears when cyclic ambiguity resolution is required. The argument for using winning votes follows from this: Because cycle resolution involves disenfranchising a selection of votes, then the selection should disenfranchise the fewest possible number of votes. When margins are used, the difference between the number of two candidates' votes may be small, but the number of votes may be very large—or not. Only methods employing winning votes satisfy Woodall's plurality criterion.

An argument in favour of using margins is the fact that the result of a pairwise comparison is decided by the presence of more votes for one side than the other and thus that it follows naturally to assess the strength of a comparison by this "surplus" for the winning side. Otherwise, changing only a few votes from the winner to the loser could cause a sudden large change from a large score for one side to a large score for the other. In other words, one could consider losing votes being in fact disenfranchised when it comes to ambiguity resolution with winning votes. Also, using winning votes, a vote containing ties (possibly implicitly in the case of an incompletely ranked ballot) does not have the same effect as a number of equally weighted votes with total weight equaling one vote, such that the ties are broken in every possible way (a violation of Woodall's symmetric-completion criterion), as opposed to margins.[27]

Under winning votes, if two more of the "B" voters decided to vote "BC", the A->C arm of the cycle would be overturned and Condorcet would pick C instead of B. This is an example of "Unburying" or "Later does harm". The margin method would pick C anyway.

Under the margin method, if three more "BC" voters decided to "bury" C by just voting "B", the A->C arm of the cycle would be strengthened and the resolution strategies would end up breaking the C->B arm and giving the win to B. This is an example of "Burying". The winning votes method would pick B anyway.

Related terms

[edit]Other terms related to the Condorcet method are:

- Condorcet loser

- [citation needed] the candidate who is less preferred than every other candidate in a pairwise matchup (preferred by fewer voters than any other candidate).

- Weak Condorcet winner

- [citation needed] a candidate who beats or ties with every other candidate in a pairwise matchup (preferred by at least as many voters as any other candidate). There can be more than one weak Condorcet winner.[28]

- Weak Condorcet loser

- [citation needed] a candidate who is defeated by or ties with every other candidate in a pairwise matchup. Similarly, there can be more than one weak Condorcet loser.

- Improved Condorcet winner

- [citation needed] in improved condorcet methods, additional rules for pairwise comparisons are introduced to handle ballots where candidates are tied, so that pairwise wins can not be changed by those tied ballots switching to a specific preference order. A strong improved condorcet winner in an improved condorcet method must also be a strong condorcet winner, but the converse need not hold. In tied at the top methods, the number of ballots where the candidates are tied at the top of the ballot is subtracted from the victory margin between the two candidates. This has the effect of introducing more ties in the pairwise comparison graph, but allows the method to satisfy the favourite betrayal criterion.

Condorcet ranking methods

[edit]Some Condorcet methods produce not just a single winner, but a ranking of all candidates from first to last place. A Condorcet ranking is a list of candidates with the property that the Condorcet winner (if one exists) comes first and the Condorcet loser (if one exists) comes last, and this holds recursively for the candidates ranked between them.

Single winner methods that satisfy this property include:

Proportional forms which satisfy this property include:

Though there will not always be a Condorcet winner or Condorcet loser, there is always a Smith set and "Smith loser set" (smallest group of candidates who lose to all candidates not in the set in head-to-head elections). Some voting methods produce rankings that sort all candidates in the Smith set above all others, and all candidates in the Smith loser set below all others, with this holding recursively for all candidates ranked between them; in essence, this guarantees that when the candidates can be split into two groups, such that every candidate in the first group beats every candidate in the second group head-to-head, then all candidates in the first group are ranked higher than all candidates in the second group.[29] Because the Smith set and Smith loser set are equivalent to the Condorcet winner and Condorcet loser when they exist, methods that always produce Smith set rankings also always produce Condorcet rankings.

Comparison with instant runoff and first-past-the-post (plurality)

[edit]This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (November 2020) |

One claim of some instant-runoff voting (IRV) proponents is that if a voter's first choice does not win, then their vote will transfer to their second choice; if their second choice does not win, their vote will transfer to their third choice, etc. In practice, it is not true for every voter with IRV. If someone voted for a strong candidate, and their 2nd and 3rd choices are eliminated before their first choice is eliminated, IRV transfers their vote to their 4th choice candidate, not their 2nd choice. Condorcet voting takes all rankings into account simultaneously, but at the expense of violating the later-no-harm criterion and the later-no-help criterion. With IRV, indicating a second choice will never affect your first choice. With Condorcet voting, it is possible that indicating a second choice will cause your first choice to lose.

Plurality voting is simple, and theoretically provides incentives for voters to compromise for centrist candidates rather than throw away their votes on candidates who cannot win. Opponents to plurality voting point out that voters often vote for the lesser of evils because they heard on the news that those two are the only two with a chance of winning, not necessarily because those two are the two natural compromises. This gives the media significant election powers. And if voters do compromise according to the media, the post election counts will prove the media right for next time. Condorcet runs each candidate against the other head to head, so that voters elect the candidate who would win the most sincere runoffs, instead of the one they thought they had to vote for.

There are circumstances, as in the examples above, when both instant-runoff voting and the "first-past-the-post" plurality system will fail to pick the Condorcet winner. (In fact, FPTP can elect the Condorcet loser and IRV can elect the second-worst candidate, who would lose to every candidate except the Condorcet loser.[30]) In cases where there is a Condorcet Winner, and where IRV does not choose it, a majority would by definition prefer the Condorcet Winner to the IRV winner. Proponents of the Condorcet criterion see it as a principal issue in selecting an electoral system. They see the Condorcet criterion as a natural extension of majority rule. Condorcet methods tend to encourage the selection of centrist candidates who appeal to the median voter. Here is an example that is designed to support IRV at the expense of Condorcet:

| 499 voters | 3 voters | 498 voters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. B | 2. C | 2. B |

| 3. C | 3. A | 3. A |

B is preferred by a 501–499 majority to A, and by a 502–498 majority to C. So, according to the Condorcet criterion, B should win, despite the fact that very few voters rank B in first place. By contrast, IRV elects C and plurality elects A. The goal of a ranked voting system is for voters to be able to vote sincerely and trust the system to protect their intent. Plurality voting forces voters to do all their tactics before they vote, so that the system does not need to figure out their intent.

The significance of this scenario, of two parties with strong support, and the one with weak support being the Condorcet winner, may be misleading, though, as it is a common mode in plurality voting systems (see Duverger's law), but much less likely to occur in Condorcet or IRV elections, which unlike Plurality voting, punish candidates who alienate a significant block of voters.

Here is an example that is designed to support Condorcet at the expense of IRV:

| 33 voters | 16 voters | 16 voters | 35 voters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. B | 2. A | 2. C | 2. B |

| 3. C | 3. C | 3. A | 3. A |

B would win against either A or C by more than a 65–35 margin in a one-on-one election, but IRV eliminates B first, leaving a contest between the more "polar" candidates, A and C. Proponents of plurality voting state that their system is simpler than any other and more easily understood.

All three systems are susceptible to tactical voting, but the types of tactics used and the frequency of strategic incentive differ in each method.

Potential for tactical voting

[edit]Like all voting methods,[31] Condorcet methods are vulnerable to compromising. That is, voters can help avoid the election of a less-preferred candidate by insincerely raising the position of a more-preferred candidate on their ballot. However, Condorcet methods are only vulnerable to compromising when there is a majority rule cycle, or when one can be created.[32]

Condorcet methods are vulnerable to burying. In some elections, voters can help a more-preferred candidate by insincerely lowering the position of a less-preferred candidate on their ballot. For example, in an election with three candidates, voters may be able to falsify their second choice to help their preferred candidate win.

Example with the Schulze method:

| 46 voters | 44 voters | 10 voters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. B | 2. A | 2. B |

| 3. C | 3. C | 3. A |

- B is the sincere Condorcet winner. But since A has the most votes and almost has a majority, with A and B forming a mutual majority of 90% of the voters, A can win by publicly instructing A voters to bury B with C (see * below), using B-top voters' 2nd choice support to win the election. If B, after hearing the public instructions, reciprocates by burying A with C, C will be elected, and this threat may be enough to keep A from pushing for his tactic. B's other possible recourse would be to attack A's ethics in proposing the tactic and call for all voters to vote sincerely. This is an example of the chicken dilemma.

| 46 voters | 44 voters | 10 voters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. C* | 2. A | 2. B |

| 3. B* | 3. C | 3. A |

- B beats A by 8 as before, and A beats C by 82 as before, but now C beats B by 12, forming a Smith set greater than one. Even the Schulze method elects A: The path strength of A beats B is the lesser of 82 and 12, so 12. The path strength of B beats A is only 8, which is less than 12, so A wins. B voters are powerless to do anything about the public announcement by A, and C voters just hope B reciprocates, or maybe consider compromise voting for B if they dislike A enough.

Supporters of Condorcet methods which exhibit this potential problem could rebut this concern by pointing out that pre-election polls are most necessary with plurality voting, and that voters, armed with ranked choice voting, could lie to pre-election pollsters, making it impossible for Candidate A to know whether or how to bury. It is also nearly impossible to predict ahead of time how many supporters of A would actually follow the instructions, and how many would be alienated by such an obvious attempt to manipulate the system.

| 33 voters | 16 voters | 16 voters | 35 voters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A | 1. B | 1. B | 1. C |

| 2. B | 2. A | 2. C | 2. B |

| 3. C | 3. C | 3. A | 3. A |

- In the above example, if C voters bury B with A, A will be elected instead of B. Since C voters prefer B to A, only they would be hurt by attempting the burying. Except for the first example where one candidate has the most votes and has a near majority, the Schulze method is very resistant to burying.

Evaluation by criteria

[edit]Scholars of electoral systems often compare them using mathematically defined voting system criteria. The criteria which Condorcet methods satisfy vary from one Condorcet method to another. However, the Condorcet criterion is incompatible with the consistency, independence of irrelevant alternatives (though it implies a weaker analogous form of IIA: when there is a Condorcet winner, losing candidates can drop out of the election without changing the result),[33] later-no-harm, later-no-help, participation, and sincere favorite criteria.

Voting system criterion Condorcet method |

Monotonic | Condorcet loser |

Clone independence |

Reversal symmetry |

Polynomial time |

Resolvable | Local independence of irrelevant alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schulze | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ranked Pairs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Minimax | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Nanson | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown |

| Kemeny | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Dodgson | No | No | No | No | No | Unknown | Unknown |

| Copeland | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Use of Condorcet voting

[edit]

Condorcet methods are not known to be currently in use in government elections anywhere in the world, but a Condorcet method known as Nanson's method was used in city elections in the U.S. town of Marquette, Michigan in the 1920s,[34] and today Condorcet methods are used by a number of political parties and private organizations.

In Vermont, Bill H.424[35] would enable towns, cities, and villages to adopt a Condorcet-based voting system for single-seat office elections through a majority vote at a town meeting. The system first checks for a majority winner among first preferences. If none, pairwise Condorcet comparisons are counted and the Condorcet winner is elected. If none, it resorts to a first-past-the-post tiebreaker. Once adopted, the system remains in effect until the community decides to revert to a previous method or another system through a subsequent town meeting vote.

Organizations which currently use some variant of the Condorcet method are:

- The Libertarian Party of Washington allows for a Condorcet method, in addition to other systems[36]

- The Free State Project used Minimax for choosing its target state

- The uk.* hierarchy of Usenet uses a Condorcet method[37]

- Baldwin's method was in use by the Trinity College Dialectic Society around 1864.[38]

- Schulze method is used in many places. Some examples:

- The Wikimedia Foundation used the Schulze method to elect its Board of Trustees until 2013, when it switched to a ratings ballot with Support/Neutral/Oppose ballots.[39]

- The Pirate Party of Sweden uses the Schulze method for its primaries

- The Debian project uses the Schulze method for internal referendums and to elect its leader

- The Software in the Public Interest corporation uses the Schulze method for internal referendums and to elect its board of directors

- The Gentoo Foundation uses the Schulze method for internal referendums and to elect its board of trustees and its council

- Kingman Hall and Hillegass Parker House, two loosely affiliated student housing cooperatives, each use the Schulze method to elect their management teams.

- The Kubernetes community uses Elekto's implementation of the Schulze method.[40]

- The Schulze method article has a longer list of users of that method.

See also

[edit]- Condorcet loser criterion

- Condorcet's jury theorem

- Ramon Llull (1232–1315) who, with the 2001 discovery of his lost manuscripts Ars notandi, Ars eleccionis, and Alia ars eleccionis, was given credit for discovering the Borda count and Condorcet criterion (Llull winner) in the 13th century

- Multiwinner voting—contains information on some multiwinner variants of Condorcet methods.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The largest bloc (plurality) of first place votes is 42% for Memphis; no other rankings are considered. So even though 58%—a true majority—would be inconvenienced by having the capital at the most remote location, Memphis wins.

- ^ Chattanooga (15%) is eliminated in the first round; votes transfer to Knoxville. Nashville (26%) eliminated in the second around; votes transfer to Knoxville. Knoxville wins with 58%.

References

[edit]- ^ Gehrlein, William V.; Valognes, Fabrice (2001). "Condorcet efficiency: A preference for indifference". Social Choice and Welfare. 18: 193–205. doi:10.1007/s003550000071. S2CID 10493112.

The Condorcet winner in an election is the candidate who would be able to defeat all other candidates in a series of pairwise elections.

- ^ Gehrlein, William V. (2006). Condorcet's paradox. Theory and decision library Series C, Game theory, mathematical programming and operations research. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-33798-0.

And, this is why the PMRW is commonly referred to as the Condorcet Winner.

- ^ Tideman, T. Nicolaus; Plassmann, Florenz (2011). "Modeling the Outcomes of Vote-Casting in Actual Elections". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1627787. ISSN 1556-5068.

A common definition of a voting cycle is the absence of a strict pairwise majority rule winner (SPMRW) … if no candidate beats all other candidates in pairwise comparisons.

- ^ Green-Armytage, James (2011). "Four Condorcet-Hare Hybrid Methods for Single-Winner Elections" (PDF). S2CID 15220771. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-03.

- ^ Wallis, W. D. (2014). "Simple Elections II: Condorcet's Method". The Mathematics of Elections and Voting. Springer. pp. 19–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-09810-4_3. ISBN 978-3-319-09809-8.

- ^ Gehrlein, William V.; Fishburn, Peter C. (1976). "Condorcet's Paradox and Anonymous Preference Profiles". Public Choice. 26: 1–18. doi:10.1007/BF01725789. JSTOR 30022874?seq=1. S2CID 153482816.

Condorcet's paradox [6] of simple majority voting occurs in a voting situation [...] if for every alternative there is a second alternative which more voters prefer to the first alternative than conversely.

- ^ Johnson, Paul E. (May 27, 2005). "Voting Systems" (PDF).

Formally, the Smith set is defined as the smaller of two sets:

1. The set of all alternatives, X.

2. A subset A ⊂ X such that each member of A can defeat every member of X that is not in A, which we call B=X − A. - ^ G. Hägele and F. Pukelsheim (2001). "Llull's writings on electoral systems". Studia Lulliana. 41: 3–38. Archived from the original on 2006-02-07.

- ^ Colomer, Josep (2013). "Ramon Llull: From Ars Electionis to Social Choice Theory". Social Choice and Welfare. 40 (2): 317–328. doi:10.1007/s00355-011-0598-2. hdl:10261/125715. S2CID 43015882.

- ^ McLean, Iain; Urken, Arnold B. (1992). "Did Jefferson or Madison understand Condorcet's theory of social choice?". Public Choice. 73 (4): 445–457. doi:10.1007/BF01789561. S2CID 145167169.

Binary procedures of the Jefferson/Robert variety will select the Condorcet winner if one exists

- ^ "Ranked Robin". Equal Vote Coalition. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ "Ranked Robin". electowiki. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- ^ Gehrlein, William V. (2011). Voting paradoxes and group coherence : the condorcet efficiency of voting rules. Lepelley, Dominique. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9783642031076. OCLC 695387286.

empirical studies ... indicate that some of the most common paradoxes are relatively unlikely to be observed in actual elections. ... it is easily concluded that Condorcet's Paradox should very rarely be observed in any real elections on a small number of candidates with large electorates, as long as voters' preferences reflect any reasonable degree of group mutual coherence

- ^ Darlington, Richard B. (2018). "Are Condorcet and minimax voting systems the best?". arXiv:1807.01366 [physics.soc-ph].

CC [Condorcet] systems typically allow tied ranks. If a voter fails to rank a candidate, they are typically presumed to rank them below anyone whom they did rank explicitly.

- ^ Hazewinkel, Michiel (2007-11-23). Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Supplement III. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-306-48373-8.

Briefly, one can say candidate A defeats candidate B if a majority of the voters prefer A to B. With only two candidates [...] barring ties [...] one of the two candidates will defeat the other.

- ^ Wang, Tiance; Cuff, P.; Kulkarni, Sanjeev (2013). "Condorcet Methods are Less Susceptible to Strategic Voting" (PDF). S2CID 8230466. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-02.

- ^ a b c d Pacuit, Eric (2019), "Voting Methods", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2020-10-16

- ^ Thesis [permanent dead link] "IRV satisfies the later-no-harm criterion and the Condorcet loser criterion but fails monotonicity, independence of irrelevant alternatives, and the Condorcet criterion."

- ^ "Condorcet". Equal Vote Coalition. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Igersheim, Herrade; Durand, François; Hamlin, Aaron; Laslier, Jean-François (January 2022). "Comparing voting methods: 2016 US presidential election". European Journal of Political Economy. 71 102057. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2021.102057.

- ^ a b Mackie, Gerry. (2003). Democracy defended. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0511062648. OCLC 252507400.

- ^ Nurmi, Hannu (2012), "On the Relevance of Theoretical Results to Voting System Choice", in Felsenthal, Dan S.; Machover, Moshé (eds.), Electoral Systems, Studies in Choice and Welfare, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 255–274, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20441-8_10, ISBN 9783642204401, S2CID 12562825

- ^ a b Young, H. P. (1988). "Condorcet's Theory of Voting" (PDF). American Political Science Review. 82 (4): 1231–1244. doi:10.2307/1961757. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1961757. S2CID 14908863. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-22.

- ^ Hogben, G. (1913). "Preferential Voting in Single-member Constituencies, with Special Reference to the Counting of Votes". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 46: 304–308.

- ^ "Smith Score - electowiki". electowiki.org. Retrieved 2024-12-14.

- ^ Behrens, Jan; Kistner, Axel; Nitsche, Andreas; Swierczek, Bjorn (2014). "The Principles of Liquid Feedback" (PDF) (1 ed.).

- ^ Woodall, D R. "Properties of Preferential Election Rules". Voting Matters (3): 8–15. Retrieved 2024-12-14.

- ^ Felsenthal, Dan S.; Tideman, Nicolaus (2014). "Weak Condorcet winner(s) revisited". Public Choice. 160 (3–4): 313–326. doi:10.1007/s11127-014-0180-4. S2CID 154447142.

A weak Condorcet winner (WCW) is an alternative, y, that no majority of voters rank below any other alternative, z, but is not a SCW [Condorcet winner].

- ^ Truchon, Michel (October 1998). "AN EXTENSION OF THE CONDORCET CRITERION AND KEMENY ORDERS" (PDF).

A first objective of this paper is to propose a formalization of this idea, called the Extended Condorcet Criterion (XCC). In essence, it says that if the set of alternatives can be partitioned in such a way that all members of a subset of this partition defeat all alternatives belonging to subsets with a higher index, then the former should obtain a better rank than the latter.

- ^ Nanson, E. J. (1882). "Methods of election". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria. 19: 207–208.

although Ware's method cannot return the worst, it may return the next worst.

- ^ Satterthwaite, Mark. "Strategy-proofness and Arrow's conditions: Existence and correspondence theorems for voting procedures and social welfare functions".

- ^ Green-Armytage, James. "Why majoritarian election methods should be Condorcet-efficient". Economics. S2CID 18348996.

- ^ Schulze, Markus (2018). "The Schulze Method of Voting". p. 351. arXiv:1804.02973 [cs.GT].

The Condorcet criterion for single-winner elections (section 4.7) is important because, when there is a Condorcet winner b ∈ A, then it is still a Condorcet winner when alternatives a1,...,an ∈ A \ {b} are removed. So an alternative b ∈ A doesn't owe his property of being a Condorcet winner to the presence of some other alternatives. Therefore, when we declare a Condorcet winner b ∈ A elected whenever a Condorcet winner exists, we know that no other alternatives a1,...,an ∈ A \ {b} have changed the result of the election without being elected.

- ^ McLean (2002), Australian electoral reform and two concepts of representation (PDF) (paper), UK: Ox, retrieved 2015-06-27

- ^ "Bill Status H.424". legislature.vermont.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ "Constitution of the Libertarian Party of Washington State" (PDF). Libertarian Party of Washington. March 26, 2022. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-14.

then the vote shall be performed using either a Condorcet voting system or a score voting system, as the participants shall decide

- ^ "Guidelines for Group Creation for uk.*". www.usenet.org.uk. Retrieved 2024-12-13.

For a vote between several mutually exclusive options, the votetaking organisation will establish, for each possible pair of options A and B, how many voters prefer A over B and vice versa. … The method of determining the result when there are several mutually exclusive options, as described in paragraph 4 of The Result, is essentially that devised by the French mathematician the Marquis de Condorcet (1743-94).

- ^ Nanson, E. J. (1882). "Methods of election". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria. 19: 217.

- ^ "Wikimedia Foundation elections 2013/Results – Meta". meta.wikimedia.org. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ^ "Goldydocs". Elekto. Retrieved 2024-12-14.

Further reading

[edit]- Black, Duncan (1958). The Theory of Committees and Elections. Cambridge University Press.

- Farquarson, Robin (1969). Theory of Voting. Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sen, Amartya Kumar (1970). Collective Choice and Social Welfare. Holden-Day. ISBN 978-0-8162-7765-0.

External links

[edit]- Johnson, Paul E, Voting Systems (PDF), Free faculty, retrieved 2015-06-27.

- Lanphier, Robert ‘Rob’, Condorcet's Method.

- Loring, Robert ‘Rob’, Accurate Democracy, archived from the original on 2004-10-30, retrieved 2004-11-02.

- McKinnon, Ron, Condorcet Canada Initiative, CA, retrieved 2019-01-08. Multipage description of Condorcet method and Ranked Pairs from a Canadian perspective.

- Perez, Joaquin, A strong No Show Paradox is a common flaw in Condorcet voting correspondences (PDF), ES: UAH, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03, retrieved 2015-06-27.

- Prabhakar, Ernest (2010-06-28), Maximum Majority Voting (a Condorcet method), Radical centrism, retrieved 2015-06-27.

- Schulze, Markus, A New Monotonic, Clone-Independent, Reversal Symmetric, and Condorcet-Consistent Single-Winner Election Method (PDF).

Software

[edit]- BipartiVox (Free & Simple Online Condorcet Voting using the Bipartisan/Range method), archived from the original on 2024-02-23, retrieved 2023-09-11.

- CIVS, a free web poll service using the Condorcet method, Cornell.

- Condorcet PHP (Open-source command line application and PHP library for computing multiple Condorcet methods and others), 22 October 2021.

- Preference Sort Voting (Open-source plugin for Moodle), Odei Alba, 2 June 2023

- Condorcet.Vote (A free web poll application using the original Condorcet method and many others like Schulze method.)

- DEbian VOTe EnginE (A Free Software vote engine using the Schulze method.)

- Gorr, Eric, Condorcet Voting Calculator.

- Hivemind (A free mobile app for ranked choice voting that uses the Condorcet method.).

- STV (software for computing Condorcet methods and STV), Sourceforge.

- VoteFair surveys (Free ranking service that calculates Condorcet–Kemeny results), VoteFair

- VoteFair Ranking (Open-source C++ election software that calculates Condorcet–Kemeny results.), VoteFair, 25 September 2021

- w.c.s. (A free web poll application using OpenSTV for voting algorithms), Entr'ouvert

Condorcet method

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Definition and Principle

The Condorcet method refers to a class of ranked voting systems that identify a winner through pairwise comparisons of candidates based on voter preference rankings. In this approach, voters order candidates from most to least preferred, enabling the computation of majority preferences for every possible head-to-head matchup between candidates. A candidate who receives majority support against each opponent—known as the Condorcet winner—is selected as the victor, as this candidate demonstrably outperforms all rivals in direct contests.[6][9] Named after the Marquis de Condorcet, who introduced the concept in his 1785 treatise Essai sur l'application de l'analyse à la probabilité des décisions rendues à la pluralité des voix, the method's principle centers on aggregating individual preferences to reveal the candidate most broadly acceptable to the electorate.[11][9] By prioritizing pairwise majorities over simplistic first-choice tallies, it aims to align outcomes with the median voter's preferences, reducing the risk of electing candidates who lack majority support against key alternatives.[6] This framework satisfies the Condorcet criterion, mandating the election of any existing pairwise-dominant candidate, and theoretically promotes compromise by favoring positions that bridge voter divides rather than extremes. Empirical analyses of elections using ranked ballots, such as 183 out of 185 U.S. ranked-choice voting contests and 154 out of 155 New South Wales elections, confirm the near-universal existence of a Condorcet winner in practice.[6][9]Historical Development

The Condorcet method traces its origins to the Marquis de Condorcet, who in 1785 published Essai sur l'application de l'analyse à la probabilité des décisions rendues à la pluralité des voix, a treatise applying probability theory to majority voting in juries and assemblies.[12] In this 495-page work, Condorcet argued that the rationally superior decision is the option prevailing in every pairwise majority comparison against alternatives, emphasizing empirical aggregation of individual judgments over simple plurality.[12] He demonstrated through examples that plurality could yield suboptimal outcomes, such as electing a candidate rejected by a majority in direct contests, and identified intransitive cycles in voter preferences—now termed the Condorcet paradox—where no pairwise-dominant option exists.[13] Condorcet's ideas emerged from Enlightenment debates on rational governance, particularly his opposition to Jean-Charles de Borda's 1770 positional count method within the French Academy of Sciences, which weighted ranks by inverse order (e.g., first-place votes scoring highest).[14] Condorcet critiqued Borda for undervaluing head-to-head majorities, insisting pairwise victories better reflect collective will, though he acknowledged probabilistic uncertainties in large electorates and proposed jury theorems linking voter competence to decision accuracy.[14] His framework prioritized causal efficacy in preference revelation over arithmetic convenience, but practical implementation lagged amid the French Revolution, during which Condorcet perished in 1794.[12] In the mid-19th century, British mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (pen name Lewis Carroll) independently advanced Condorcet principles through pamphlets on proportional representation and committee selection, notably his 1873 A Method of Apportioning Representation and 1876 A Method of Taking Account of "Sympathies" and of "Antipathies" between Members of Different Constituencies.[15] Dodgson proposed resolving absent Condorcet winners by minimally altering voter rankings to create one, using a scoring metric for swaps, thus extending pairwise logic to cyclic scenarios while preserving majority pairwise beats where possible.[15] These efforts, aimed at university and parliamentary reforms, highlighted computational challenges but influenced later positional adjustments in Condorcet variants.[16] Twentieth-century formalization occurred via social choice theory, with economists like Duncan Black rediscovering Condorcet criteria in 1948 analyses of single-peaked preferences, where dimension restrictions eliminate cycles.[13] Kenneth Arrow's 1951 impossibility theorem underscored Condorcet methods' appeal despite non-existence risks, spurring variants like Copeland scoring (1876 onward, formalized later) that rank by pairwise victories.[13] Empirical adoption remained niche, confined to organizations like the American Mathematical Society (testing in the 1970s) and software for preferential ballots, reflecting persistent cycle-handling barriers over plurality's simplicity.[9]Implementation Mechanics

Ballot Structure and Voter Preferences

In Condorcet methods, ballots require voters to rank candidates ordinally, typically from most preferred to least preferred, to derive pairwise preference counts. This ranked-choice format provides a complete or partial ordering that implies voter preferences in every head-to-head matchup: a voter prefers candidate A over B if A appears higher in their ranking than B.[2][10] Voters may submit incomplete rankings by omitting some candidates, which implementations handle by assuming indifference or lower preference for unranked options relative to ranked ones, ensuring all pairwise comparisons can still be computed across the electorate. Ties between candidates can also be expressed on ballots, with such equal rankings treated as half-votes for each in pairwise tallies or excluded from strict preference counts, varying by method variant.[2][10] Although direct pairwise ballots—requiring voters to select a preferred candidate in each possible duo—avoid reliance on inferred transitivity and could reduce strategic incentives tied to full rankings, ranked ballots predominate for their efficiency in eliciting comprehensive preferences with fewer voter decisions.[6] Ranked ballots thus form the standard structure, enabling the Condorcet criterion's focus on majority pairwise victories while accommodating real-world voting behaviors like abstentions from full rankings.[6][2]Pairwise Comparison Computation

The pairwise comparison computation forms the core of the Condorcet method, deriving direct majority preferences between candidates from ranked ballots. For every distinct pair of candidates and , the process tallies the number of voters who rank above , denoted as , against those who rank above , denoted as .[17][18] A candidate defeats if ; the comparison results in a tie if .[17] Voters indifferent between and (e.g., via equal rankings, if permitted) or omitting one do not contribute to either tally, though strict rankings are standard to ensure completeness.[18] This computation yields a set of pairwise outcomes for all pairs among candidates, often aggregated into a preference matrix where records the net margin , with positive values indicating defeats .[19] The matrix is antisymmetric () and reveals the tournament structure of preferences. Computationally, for voters, a straightforward algorithm iterates over each ballot to compare relative positions of candidates in each pair, accumulating counts; this requires operations before aggregation.[20] To illustrate, consider three candidates , , and with hypothetical voter rankings from 5 ballots:| Voter | Ranking |

|---|---|

| 1-2 | A > B > C |

| 3 | B > C > A |

| 4 | C > A > B |

| 5 | A > C > B |

Winner Selection and Cycle Handling

The Condorcet winner is selected as the victor in elections employing the Condorcet method when such a candidate exists, defined as the one who prevails in every pairwise majority comparison against all other contenders based on aggregated voter rankings.[3][21] Pairwise victories are tallied by counting, for each candidate pair, the number of voters ranking one above the other; a candidate secures a win if supported by a strict majority in that matchup.[22] This process constructs a complete preference graph where directed edges indicate majority preferences, and the Condorcet winner corresponds to the unique source node with outgoing edges to all others.[9] Absence of a Condorcet winner arises from cyclic majorities in the pairwise comparisons, a phenomenon formalized as the Condorcet paradox, where transitive individual preferences aggregate into intransitive social outcomes, such as candidate A defeating B, B defeating C, and C defeating A.[23] In these scenarios, the method's basic form fails to produce a decisive outcome, as no candidate satisfies the universal pairwise dominance condition.[24] Empirical analyses of non-political elections indicate cycles occur infrequently, with Condorcet winners present in over 90% of examined cases from ranked-choice data sets spanning sports, food preferences, and organizational votes.[25] Cycle handling in the strict Condorcet framework typically involves declaring no winner or a tie among the top cycle participants, though this undecisiveness has prompted extensions like iterative elimination of pairwise losers or auxiliary tie-breaking rules to ensure a selection.[9] Such resolutions prioritize preserving the Condorcet criterion—electing the pairwise-dominant candidate when available—while addressing paradoxes through minimal deviation from majority pairwise data.Illustrative Scenarios

Condorcet Winner Example

Consider an election among three candidates—Anaheim (A), Orlando (O), and Hawaii (H)—with ten voters submitting ranked-choice ballots. The preference profile is summarized in the following table:| Number of voters | 1st choice | 2nd choice | 3rd choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | O | H |

| 3 | A | H | O |

| 3 | O | H | A |

| 3 | H | A | O |

Cycle Formation and Paradox Demonstration

In certain preference profiles, the Condorcet method fails to produce a Condorcet winner due to the formation of cycles in the pairwise majority preference relation, a situation known as the Condorcet paradox. This occurs when the aggregate voter preferences yield intransitive social choices, such as candidate A defeating B by majority, B defeating C by majority, and C defeating A by majority, forming a loop with no candidate superior to all others in head-to-head matchups. The paradox was first formally described by the Marquis de Condorcet in 1785, illustrating that even under sincere voting with full preference rankings, majority rule can violate transitivity, a core assumption in rational choice theory.[27] A standard demonstration involves three candidates (A, B, C) and three voters expressing linear preferences as follows:| Voter | Ranking |

|---|---|

| 1 | A > B > C |

| 2 | B > C > A |

| 3 | C > A > B |

- A versus B: A wins 2–1 (voters 1 and 3 prefer A to B).

- B versus C: B wins 2–1 (voters 1 and 2 prefer B to C).

- C versus A: C wins 2–1 (voters 2 and 3 prefer C to A).

Variant Approaches

Hybrid Two-Stage Systems

Hybrid two-stage systems represent variants of Condorcet methods that incorporate a primary stage focused on identifying a Condorcet winner through pairwise majority comparisons, followed by a secondary stage applying a non-Condorcet rule—such as Borda count, plurality, or iterative elimination—to resolve cycles when no candidate pairwise defeats all others. These hybrids ensure deterministic outcomes while attempting to uphold the Condorcet criterion whenever possible, addressing the method's vulnerability to the Condorcet paradox where cyclic preferences prevent a clear winner. By design, they elect the Condorcet winner if one exists, thereby satisfying the Condorcet criterion in those cases, but deviate otherwise to prioritize alternative majority or positional metrics.[31][32] Black's procedure exemplifies an early hybrid approach, first checking for a Condorcet winner across all candidates; absent one, it falls back to the Borda count winner, which ranks candidates by aggregating ordinal preferences into point totals (e.g., n-1 points for first place in an n-candidate race, decreasing sequentially). This method, analyzed in computational social choice literature, balances Condorcet consistency with Borda's positional strengths, though it remains susceptible to manipulation in the secondary stage.[31][33] Condorcet-plurality hybrids simplify resolution by using first-past-the-post (FPTP) tallies of first-choice votes as the tiebreaker, electing the Condorcet winner if present or the candidate with the most first preferences otherwise. Variants like Smith//Plurality refine this by first isolating the Smith set—the minimal nonempty subset where every member pairwise defeats all outsiders—then applying plurality within it after vote transfers from eliminated candidates to their highest-ranked Smith set member. These systems have been proposed for practical implementation, such as in Vermont's 2024 legislative bill H.424, emphasizing ease of computation and resistance to certain strategic behaviors over full cycle resolution.[34] Condorcet-Hare (or IRV) hybrids integrate sequential elimination akin to instant-runoff voting (IRV, or Hare method) with Condorcet checks. The Benham method, for instance, iteratively eliminates the plurality loser (lowest first-choice votes) and recalculates pairwise margins among survivors until a Condorcet winner emerges, guaranteeing selection of the Condorcet winner if one exists at any stage. Similarly, the Tideman method alternates Smith set isolation with plurality elimination, repeating until a single candidate remains within the refined set. These approaches, detailed in voting theory analyses, enhance Condorcet compliance in cyclic scenarios by leveraging elimination to break intransitivities, though they may invert IRV outcomes when a Condorcet winner is absent. Empirical evaluations indicate higher Condorcet efficiency compared to pure IRV, particularly in electorates with structured preferences.[32][35]Single-Stage Resolution Methods