Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geologic time scale

View on Wikipedia

The geologic time scale or geological time scale (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochronology (a scientific branch of geology that aims to determine the age of rocks). It is used primarily by Earth scientists (including geologists, paleontologists, geophysicists, geochemists, and paleoclimatologists) to describe the timing and relationships of events in geologic history. The time scale has been developed through the study of rock layers and the observation of their relationships and identifying features such as lithologies, paleomagnetic properties, and fossils. The definition of standardised international units of geological time is the responsibility of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), a constituent body of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), whose primary objective[1] is to precisely define global chronostratigraphic units of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart (ICC)[2] that are used to define divisions of geological time. The chronostratigraphic divisions are in turn used to define geochronologic units.[2]

Principles

[edit]The geologic time scale is a way of representing deep time based on events that have occurred through Earth's history, a time span of about 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years.[3] It chronologically organises strata, and subsequently time, by observing fundamental changes in stratigraphy that correspond to major geological or paleontological events. For example, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, marks the lower boundary of the Paleogene System/Period and thus the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene systems/periods. For divisions prior to the Cryogenian, arbitrary numeric boundary definitions (Global Standard Stratigraphic Ages, GSSAs) are used to divide geologic time. Proposals have been made to better reconcile these divisions with the rock record.[4][5]

Historically, regional geologic time scales were used[5] due to the litho- and biostratigraphic differences around the world in time equivalent rocks. The ICS has long worked to reconcile conflicting terminology by standardising globally significant and identifiable stratigraphic horizons that can be used to define the lower boundaries of chronostratigraphic units. Defining chronostratigraphic units in such a manner allows for the use of global, standardised nomenclature. The International Chronostratigraphic Chart represents this ongoing effort.

Several key principles are used to determine the relative relationships of rocks and thus their chronostratigraphic position.[6][7]

The law of superposition that states that in undeformed stratigraphic sequences the oldest strata will lie at the bottom of the sequence, while newer material stacks upon the surface.[8][9][10][7] In practice, this means a younger rock will lie on top of an older rock unless there is evidence to suggest otherwise.

The principle of original horizontality that states layers of sediments will originally be deposited horizontally under the action of gravity.[8][10][7] However, it is now known that not all sedimentary layers are deposited purely horizontally,[7][11] but this principle is still a useful concept.

The principle of lateral continuity that states layers of sediments extend laterally in all directions until either thinning out or being cut off by a different rock layer, i.e. they are laterally continuous.[8] Layers do not extend indefinitely; their limits are controlled by the amount and type of sediment in a sedimentary basin, and the geometry of that basin.

The principle of cross-cutting relationships that states a rock that cuts across another rock must be younger than the rock it cuts across.[8][9][10][7]

The law of included fragments that states small fragments of one type of rock that are embedded in a second type of rock must have formed first, and were included when the second rock was forming.[10][7]

The relationships of unconformities which are geologic features representing a gap in the geologic record. Unconformities are formed during periods of erosion or non-deposition, indicating non-continuous sediment deposition.[7] Observing the type and relationships of unconformities in strata allows geologist to understand the relative timing of the strata.

The principle of faunal succession (where applicable) that states rock strata contain distinctive sets of fossils that succeed each other vertically in a specific and reliable order.[12][7] This allows for a correlation of strata even when the horizon between them is not continuous.

Divisions of geologic time

[edit]The geologic time scale is divided into chronostratigraphic units and their corresponding geochronologic units.

- An eon is the largest geochronologic time unit and is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic eonothem.[13] There are four formally defined eons: the Hadean, Archean, Proterozoic and Phanerozoic.[2]

- An era is the second largest geochronologic time unit and is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic erathem.[14][13] There are ten defined eras: the Eoarchean, Paleoarchean, Mesoarchean, Neoarchean, Paleoproterozoic, Mesoproterozoic, Neoproterozoic, Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic, with none from the Hadean eon.[2]

- A period is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic system.[14][13] There are 22 defined periods, with the current being the Quaternary period.[2] As an exception, two subperiods are used for the Carboniferous Period.[14]

- An epoch is the second smallest geochronologic unit. It is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic series.[14][13] There are 37 defined epochs and one informal one. The current epoch is the Holocene. There are also 11 subepochs which are all within the Neogene and Quaternary.[2] The use of subepochs as formal units in international chronostratigraphy was ratified in 2022.[15]

- An age is the smallest hierarchical geochronologic unit. It is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic stage.[14][13] There are 96 formal and five informal ages.[2] The current age is the Meghalayan.

- A chron is a non-hierarchical formal geochronology unit of unspecified rank and is equivalent to a chronostratigraphic chronozone.[14] These correlate with magnetostratigraphic, lithostratigraphic, or biostratigraphic units as they are based on previously defined stratigraphic units or geologic features.

| Chronostratigraphic unit (strata) | Geochronologic unit (time) | Time span[note 1] |

|---|---|---|

| Eonothem | Eon | Several hundred million years to two billion years |

| Erathem | Era | Tens to hundreds of millions of years |

| System | Period | Millions of years to tens of millions of years |

| Series | Epoch | Hundreds of thousands of years to tens of millions of years |

| Subseries | Subepoch | Thousands of years to millions of years |

| Stage | Age | Thousands of years to millions of years |

The subdivisions Early and Late are used as the geochronologic equivalents of the chronostratigraphic Lower and Upper, e.g., Early Triassic Period (geochronologic unit) is used in place of Lower Triassic System (chronostratigraphic unit).

Rocks representing a given chronostratigraphic unit are that chronostratigraphic unit, and the time they were laid down in is the geochronologic unit, e.g., the rocks that represent the Silurian System are the Silurian System and they were deposited during the Silurian Period. This definition means the numeric age of a geochronologic unit can be changed (and is more often subject to change) when refined by geochronometry while the equivalent chronostratigraphic unit (the revision of which is less frequent) remains unchanged. For example, in early 2022, the boundary between the Ediacaran and Cambrian periods (geochronologic units) was revised from 541 Ma to 538.8 Ma but the rock definition of the boundary (GSSP) at the base of the Cambrian, and thus the boundary between the Ediacaran and Cambrian systems (chronostratigraphic units) has not been changed; rather, the absolute age has merely been refined.

Terminology

[edit]Chronostratigraphy is the element of stratigraphy that deals with the relation between rock bodies and the relative measurement of geological time.[14] It is the process where distinct strata between defined stratigraphic horizons are assigned to represent a relative interval of geologic time.

A chronostratigraphic unit is a body of rock, layered or unlayered, that is defined between specified stratigraphic horizons which represent specified intervals of geologic time. They include all rocks representative of a specific interval of geologic time, and only this time span. Eonothem, erathem, system, series, subseries, stage, and substage are the hierarchical chronostratigraphic units.[14]

A geochronologic unit is a subdivision of geologic time. It is a numeric representation of an intangible property (time).[16] These units are arranged in a hierarchy: eon, era, period, epoch, subepoch, age, and subage.[14] Geochronology is the scientific branch of geology that aims to determine the age of rocks, fossils, and sediments either through absolute (e.g., radiometric dating) or relative means (e.g., stratigraphic position, paleomagnetism, stable isotope ratios). Geochronometry is the field of geochronology that numerically quantifies geologic time.[16]

A Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) is an internationally agreed-upon reference point on a stratigraphic section that defines the lower boundaries of stages on the geologic time scale.[17] (Recently this has been used to define the base of a system)[18]

A Global Standard Stratigraphic Age (GSSA)[19] is a numeric-only, chronologic reference point used to define the base of geochronologic units prior to the Cryogenian. These points are arbitrarily defined.[14] They are used where GSSPs have not yet been established. Research is ongoing to define GSSPs for the base of all units that are currently defined by GSSAs.

The standard international units of the geologic time scale are published by the International Commission on Stratigraphy on the International Chronostratigraphic Chart; however, regional terms are still in use in some areas. The numeric values on the International Chronostratigrahpic Chart are represented by the unit Ma (megaannum, for 'million years'). For example, 201.4 ± 0.2 Ma, the lower boundary of the Jurassic Period, is defined as 201,400,000 years old with an uncertainty of 200,000 years. Other SI prefix units commonly used by geologists are Ga (gigaannum, billion years), and ka (kiloannum, thousand years), with the latter often represented in calibrated units (before present).

Naming of geologic time

[edit]The names of geologic time units are defined for chronostratigraphic units with the corresponding geochronologic unit sharing the same name with a change to the suffix (e.g. Phanerozoic Eonothem becomes the Phanerozoic Eon). Names of erathems in the Phanerozoic were chosen to reflect major changes in the history of life on Earth: Paleozoic (old life), Mesozoic (middle life), and Cenozoic (new life). Names of systems are diverse in origin, with some indicating chronologic position (e.g., Paleogene), while others are named for lithology (e.g., Cretaceous), geography (e.g., Permian), or are tribal (e.g., Ordovician) in origin. Most currently recognised series and subseries are named for their position within a system/series (early/middle/late); however, the International Commission on Stratigraphy advocates for all new series and subseries to be named for a geographic feature in the vicinity of its stratotype or type locality. The name of stages should also be derived from a geographic feature in the locality of its stratotype or type locality.[14]

Informally, the time before the Cambrian is often referred to as the Precambrian or pre-Cambrian (Supereon).[4][note 2]

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phanerozoic | 538.8 to 0 million years ago | 538.8 | From Greek φανερός (phanerós) 'visible' or 'abundant' and ζωή (zoē) 'life'. |

| Proterozoic | 2,500 to 538.8 million years ago | 1961.2 | From Greek πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier' and ζωή (zoē) 'life'. |

| Archean | 4,031 to 2,500 million years ago | 1531 | From Greek ἀρχή (archē) 'beginning, origin'. |

| Hadean | 4,567 to 4,031 million years ago | 536 | From Hades, Ancient Greek: ᾍδης, romanized: Háidēs, the god of the underworld (hell, the inferno) in Greek mythology. |

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cenozoic | 66 to 0 million years ago | 66 | From Greek καινός (kainós) 'new' and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Mesozoic | 251.9 to 66 million years ago | 185.902 | From Greek μέσο (méso) 'middle' and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Paleozoic | 538.8 to 251.9 million years ago | 286.898 | From Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old' and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Neoproterozoic | 1,000 to 538.8 million years ago | 461.2 | From Greek νέος (néos) 'new' or 'young', πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier', and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Mesoproterozoic | 1,600 to 1,000 million years ago | 600 | From Greek μέσο (méso) 'middle', πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier', and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Paleoproterozoic | 2,500 to 1,600 million years ago | 900 | From Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old', πρότερος (próteros) 'former' or 'earlier', and ζωή (zōḗ) 'life'. |

| Neoarchean | 2,800 to 2,500 million years ago | 300 | From Greek νέος (néos) 'new' or 'young' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Mesoarchean | 3,200 to 2,800 million years ago | 400 | From Greek μέσο (méso) 'middle' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Paleoarchean | 3,600 to 3,200 million years ago | 400 | From Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Eoarchean | 4,031 to 3,600 million years ago | 431 | From Greek ἠώς (ēōs) 'dawn' and ἀρχαῖος (arkhaîos) 'ancient'. |

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary | 2.6 to 0 million years ago | 2.58 | First introduced by Jules Desnoyers in 1829 for sediments in France's Seine Basin that appeared to be younger than Tertiary[note 3] rocks.[22] |

| Neogene | 23 to 2.6 million years ago | 20.46 | Derived from Greek νέος (néos) 'new' and γενεά (geneá) 'genesis' or 'birth'. |

| Paleogene | 66 to 23 million years ago | 42.96 | Derived from Greek παλιός (palaiós) 'old' and γενεά (geneá) 'genesis' or 'birth'. |

| Cretaceous | ~143.1 to 66 million years ago | ~77.1 | Derived from Terrain Crétacé used in 1822 by Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in reference to extensive beds of chalk within the Paris Basin.[23] Ultimately derived from Latin crēta 'chalk'. |

| Jurassic | 201.4 to 143.1 million years ago | ~58.3 | Named after the Jura Mountains. Originally used by Alexander von Humboldt as 'Jura Kalkstein' (Jura limestone) in 1799.[24] Alexandre Brongniart was the first to publish the term Jurassic in 1829.[25][26] |

| Triassic | 251.9 to 201.4 million years ago | 50.502 | From the Trias of Friedrich August von Alberti in reference to a trio of formations widespread in southern Germany. |

| Permian | 298.9 to 251.9 million years ago | 46.998 | Named after the historical region of Perm, Russian Empire.[27] |

| Carboniferous | 358.9 to 298.9 million years ago | 59.96 | Means 'coal-bearing', from the Latin carbō (coal) and ferō (to bear, carry).[28] |

| Devonian | 419.6 to 358.9 million years ago | 60.76 | Named after Devon, England.[29] |

| Silurian | 443.1 to 419.6 million years ago | 23.48 | Named after the Celtic tribe, the Silures.[30] |

| Ordovician | 486.9 to 443.1 million years ago | 43.75 | Named after the Celtic tribe, Ordovices.[31][32] |

| Cambrian | 538.8 to 486.9 million years ago | 51.95 | Named for Cambria, a Latinised form of the Welsh name for Wales, Cymru.[33] |

| Ediacaran | 635 to 538.8 million years ago | ~96.2 | Named for the Ediacara Hills. Ediacara is possibly a corruption of Kuyani 'Yata Takarra' 'hard or stony ground'.[34][35] |

| Cryogenian | 720 to 635 million years ago | ~85 | From Greek κρύος (krýos) 'cold' and γένεσις (génesis) 'birth'.[5] |

| Tonian | 1,000 to 720 million years ago | ~280 | From Greek τόνος (tónos) 'stretch'.[5] |

| Stenian | 1,200 to 1,000 million years ago | 200 | From Greek στενός (stenós) 'narrow'.[5] |

| Ectasian | 1,400 to 1,200 million years ago | 200 | From Greek ἔκτᾰσῐς (éktasis) 'extension'.[5] |

| Calymmian | 1,600 to 1,400 million years ago | 200 | From Greek κάλυμμᾰ (kálumma) 'cover'.[5] |

| Statherian | 1,800 to 1,600 million years ago | 200 | From Greek σταθερός (statherós) 'stable'.[5] |

| Orosirian | 2,050 to 1,800 million years ago | 250 | From Greek ὀροσειρά (oroseirá) 'mountain range'.[5] |

| Rhyacian | 2,300 to 2,050 million years ago | 250 | From Greek ῥύαξ (rhýax) 'stream of lava'.[5] |

| Siderian | 2,500 to 2,300 million years ago | 200 | From Greek σίδηρος (sídēros) 'iron'.[5] |

| Name | Time span | Duration (million years) | Etymology of name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holocene | 0.012 to 0 million years ago | 0.0117 | From Greek ὅλος (hólos) 'whole' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Pleistocene | 2.58 to 0.012 million years ago | 2.5683 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek πλεῖστος (pleîstos) 'most' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Pliocene | 5.33 to 2.58 million years ago | 2.753 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek πλείων (pleíōn) 'more' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Miocene | 23.04 to 5.33 million years ago | 17.707 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek μείων (meíōn) 'less' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Oligocene | 33.9 to 23.04 million years ago | 10.86 | Coined in the 1850s from Greek ὀλίγος (olígos) 'few' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Eocene | 56 to 33.9 million years ago | 22.1 | Coined in the early 1830s from Greek ἠώς (ēōs) 'dawn' and καινός (kainós) 'new', referring to the dawn of modern life during this epoch |

| Paleocene | 66 to 56 million years ago | 10 | Coined by Wilhelm Philippe Schimper in 1874 as a portmanteau of paleo- + Eocene, but on the surface from Greek παλαιός (palaios) 'old' and καινός (kainós) 'new' |

| Upper Cretaceous | 100.5 to 66 million years ago | 34.5 | See Cretaceous |

| Lower Cretaceous | 143.1 to 100.5 million years ago | 42.6 | |

| Upper Jurassic |

161.5 to 143.1 million years ago | 18.4 | See Jurassic |

| Middle Jurassic | 174.7 to 161.5 million years ago | 13.2 | |

| Lower Jurassic |

201.4 to 174.7 million years ago | 26.7 | |

| Upper Triassic | 237 to 201.4 million years ago | 35.6 | See Triassic |

| Middle Triassic |

246.7 to 237 million years ago | 9.7 | |

| Lower Triassic | 251.9 to 246.7 million years ago | 5.202 | |

| Lopingian | 259.51 to 251.9 million years ago | 7.608 | Named for Loping, China, an anglicization of Mandarin 乐平 (lèpíng) 'peaceful music' |

| Guadalupian | 274.4 to 259.51 million years ago | 14.89 | Named for the Guadalupe Mountains of the American Southwest, ultimately from Arabic وَادِي ٱل (wādī al) 'valley of the' and Latin lupus 'wolf' via Spanish |

| Cisuralian | 298.9 to 274.4 million years ago | 24.5 | From Latin cis- (before) + Russian Урал (Ural), referring to the western slopes of the Ural Mountains |

| Upper Pennsylvanian | 307 to 298.9 million years ago | 8.1 | Named for the US state of Pennsylvania, from William Penn + Latin silvanus (forest) + -ia by analogy to Transylvania |

| Middle Pennsylvanian | 315.2 to 307 million years ago | 8.2 | |

| Lower Pennsylvanian | 323.4 to 315.2 million years ago | 8.2 | |

| Upper Mississippian | 330.3 to 323.4 million years ago | 6.9 | Named for the Mississippi River, from Ojibwe ᒥᐦᓯᓰᐱ (misi-ziibi) 'great river' |

| Middle Mississippian | 346.7 to 330.3 million years ago | 16.4 | |

| Lower Mississippian | 358.86 to 346.7 million years ago | 12.16 | |

| Upper Devonian | 382.31 to 358.86 million years ago | 23.45 | See Devonian |

| Middle Devonian | 393.47 to 382.31 million years ago | 11.16 | |

| Lower Devonian | 419.62 to 393.47 million years ago | 26.15 | |

| Pridoli | 422.7 to 419.62 million years ago | 3.08 | Named for the Homolka a Přídolí nature reserve near Prague, Czechia |

| Ludlow | 426.7 to 422.7 million years ago | 4 | Named after Ludlow, England |

| Wenlock | 432.9 to 426.7 million years ago | 6.2 | Named for the Wenlock Edge in Shropshire, England |

| Llandovery | 443.1 to 432.9 million years ago | 10.2 | Named after Llandovery, Wales |

| Upper Ordovician | 458.2 to 443.1 million years ago | 15.1 | See Ordovician |

| Middle Ordovician | 471.3 to 458.2 million years ago | 13.1 | |

| Lower Ordovician | 486.85 to 471.3 million years ago | 15.55 | |

| Furongian | 497 to 486.85 million years ago | 10.15 | From Mandarin 芙蓉 (fúróng) 'lotus', referring to the state symbol of Hunan |

| Miaolingian | 506.5 to 497 million years ago | 9.5 | Named for the Miao Ling mountains of Guizhou, Mandarin for 'sprouting peaks' |

| Cambrian Series 2 (informal) | 521 to 506.5 million years ago | 14.5 | See Cambrian |

| Terreneuvian | 538.8 to 521 million years ago | 17.8 | Named for Terre-Neuve, a French calque of Newfoundland |

History of the geologic time scale

[edit]Early history

[edit]The most modern geological time scale was not formulated until 1911[36] by Arthur Holmes (1890 – 1965), who drew inspiration from James Hutton (1726–1797), a Scottish Geologist who presented the idea of uniformitarianism or the theory that changes to the Earth's crust resulted from continuous and uniform processes.[37] The broader concept of the relation between rocks and time can be traced back to (at least) the philosophers of Ancient Greece from 1200 BC to 600 AD. Xenophanes of Colophon (c. 570–487 BCE) observed rock beds with fossils of seashells located above the sea-level, viewed them as once living organisms, and used this to imply an unstable relationship in which the sea had at times transgressed over the land and at other times had regressed.[38] This view was shared by a few of Xenophanes's scholars and those that followed, including Aristotle (384–322 BC) who (with additional observations) reasoned that the positions of land and sea had changed over long periods of time. The concept of deep time was also recognized by Chinese naturalist Shen Kuo[39] (1031–1095) and Islamic scientist-philosophers, notably the Brothers of Purity, who wrote on the processes of stratification over the passage of time in their treatises.[38] Their work likely inspired that of the 11th-century Persian polymath Avicenna (Ibn Sînâ, 980–1037) who wrote in The Book of Healing (1027) on the concept of stratification and superposition, pre-dating Nicolas Steno by more than six centuries.[38] Avicenna also recognized fossils as "petrifications of the bodies of plants and animals",[40] with the 13th-century Dominican bishop Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280), who drew from Aristotle's natural philosophy, extending this into a theory of a petrifying fluid.[41] These works appeared to have little influence on scholars in Medieval Europe who looked to the Bible to explain the origins of fossils and sea-level changes, often attributing these to the 'Deluge', including Ristoro d'Arezzo in 1282.[38] It was not until the Italian Renaissance when Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) would reinvigorate the relationships between stratification, relative sea-level change, and time, denouncing attribution of fossils to the 'Deluge':[42][38]

Of the stupidity and ignorance of those who imagine that these creatures were carried to such places distant from the sea by the Deluge...Why do we find so many fragments and whole shells between the different layers of stone unless they had been upon the shore and had been covered over by earth newly thrown up by the sea which then became petrified? And if the above-mentioned Deluge had carried them to these places from the sea, you would find the shells at the edge of one layer of rock only, not at the edge of many where may be counted the winters of the years during which the sea multiplied the layers of sand and mud brought down by the neighboring rivers and spread them over its shores. And if you wish to say that there must have been many deluges in order to produce these layers and the shells among them it would then become necessary for you to affirm that such a deluge took place every year.

These views of da Vinci remained unpublished, and thus lacked influence at the time; however, questions of fossils and their significance were pursued and, while views against Genesis were not readily accepted and dissent from religious doctrine was in some places unwise, scholars such as Girolamo Fracastoro shared da Vinci's views, and found the attribution of fossils to the 'Deluge' absurd.[38] Although many theories surrounding philosophy and concepts of rocks were developed in earlier years, "the first serious attempts to formulate a geological time scale that could be applied anywhere on Earth were made in the late 18th century."[41] Later, in the 19th century, academics further developed theories on stratification. William Smith, often referred to as the "Father of Geology"[43] developed theories through observations rather than drawing from the scholars that came before him. Smith's work was primarily based on his detailed study of rock layers and fossils during his time and he created "the first map to depict so many rock formations over such a large area".[43] After studying rock layers and the fossils they contained, Smith concluded that each layer of rock contained distinct material that could be used to identify and correlate rock layers across different regions of the world.[44] Smith developed the concept of faunal succession or the idea that fossils can serve as a marker for the age of the strata they are found in and published his ideas in his 1816 book, "Strata identified by organized fossils."[44]

Establishment of primary principles

[edit]Niels Stensen, more commonly known as Nicolas Steno (1638–1686), is credited with establishing four of the guiding principles of stratigraphy.[38] In De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus Steno states:[8][45]

- When any given stratum was being formed, all the matter resting on it was fluid and, therefore, when the lowest stratum was being formed, none of the upper strata existed.

- ... strata which are either perpendicular to the horizon or inclined to it were at one time parallel to the horizon.

- When any given stratum was being formed, it was either encompassed at its edges by another solid substance or it covered the whole globe of the earth. Hence, it follows that wherever bared edges of strata are seen, either a continuation of the same strata must be looked for or another solid substance must be found that kept the material of the strata from being dispersed.

- If a body or discontinuity cuts across a stratum, it must have formed after that stratum.

Respectively, these are the principles of superposition, original horizontality, lateral continuity, and cross-cutting relationships. From this Steno reasoned that strata were laid down in succession and inferred relative time (in Steno's belief, time from Creation). While Steno's principles were simple and attracted much attention, applying them proved challenging.[38] These basic principles, albeit with improved and more nuanced interpretations, still form the foundational principles of determining the correlation of strata relative to geologic time.

Over the course of the 18th-century geologists realised that:

- Sequences of strata often become eroded, distorted, tilted, or even inverted after deposition

- Strata laid down at the same time in different areas could have entirely different appearances

- The strata of any given area represented only part of Earth's long history

Formulation of a modern geologic time scale

[edit]The apparent, earliest formal division of the geologic record with respect to time was introduced during the era of Biblical models by Thomas Burnet who applied a two-fold terminology to mountains by identifying "montes primarii" for rock formed at the time of the 'Deluge', and younger "monticulos secundarios" formed later from the debris of the "primarii".[46][38] Anton Moro (1687–1784) also used primary and secondary divisions for rock units but his mechanism was volcanic.[47][38] In this early version of the Plutonism theory, the interior of Earth was seen as hot, and this drove the creation of primary igneous and metamorphic rocks and secondary rocks formed contorted and fossiliferous sediments. These primary and secondary divisions were expanded on by Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (1712–1783) and Giovanni Arduino (1713–1795) to include tertiary and quaternary divisions.[38] These divisions were used to describe both the time during which the rocks were laid down, and the collection of rocks themselves (i.e., it was correct to say Tertiary rocks, and Tertiary Period). Only the Quaternary division is retained in the modern geologic time scale, while the Tertiary division was in use until the early 21st century. The Neptunism and Plutonism theories would compete into the early 19th century with a key driver for resolution of this debate being the work of James Hutton (1726–1797), in particular his Theory of the Earth, first presented before the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785.[48][9][49] Hutton's theory would later become known as uniformitarianism, popularised by John Playfair[50] (1748–1819) and later Charles Lyell (1797–1875) in his Principles of Geology.[10][51][52] Their theories strongly contested the 6,000 year age of the Earth as suggested determined by James Ussher via Biblical chronology that was accepted at the time by western religion. Instead, using geological evidence, they contested Earth to be much older, cementing the concept of deep time.

During the early 19th century William Smith, Georges Cuvier, Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy, and Alexandre Brongniart pioneered the systematic division of rocks by stratigraphy and fossil assemblages. These geologists began to use the local names given to rock units in a wider sense, correlating strata across national and continental boundaries based on their similarity to each other. Many of the names below erathem/era rank in use on the modern ICC/GTS were determined during the early to mid-19th century.

The advent of geochronometry

[edit]During the 19th century, the debate regarding Earth's age was renewed, with geologists estimating ages based on denudation rates and sedimentary thicknesses or ocean chemistry, and physicists determining ages for the cooling of the Earth or the Sun using basic thermodynamics or orbital physics.[3] These estimations varied from 15,000 million years to 0.075 million years depending on method and author, but the estimations of Lord Kelvin and Clarence King were held in high regard at the time due to their pre-eminence in physics and geology. All of these early geochronometric determinations would later prove to be incorrect.

The discovery of radioactive decay by Henri Becquerel, Marie Curie, and Pierre Curie laid the ground work for radiometric dating, but the knowledge and tools required for accurate determination of radiometric ages would not be in place until the mid-1950s.[3] Early attempts at determining ages of uranium minerals and rocks by Ernest Rutherford, Bertram Boltwood, Robert Strutt, and Arthur Holmes, would culminate in what are considered the first international geological time scales by Holmes in 1911 and 1913.[36][53][54] The discovery of isotopes in 1913[55] by Frederick Soddy, and the developments in mass spectrometry pioneered by Francis William Aston, Arthur Jeffrey Dempster, and Alfred O. C. Nier during the early to mid-20th century would finally allow for the accurate determination of radiometric ages, with Holmes publishing several revisions to his geological time-scale with his final version in 1960.[3][54][56][57]

Modern international geological time scale

[edit]The establishment of the IUGS in 1961[58] and acceptance of the Commission on Stratigraphy (applied in 1965)[59] to become a member commission of IUGS led to the founding of the ICS. One of the primary objectives of the ICS is "the establishment, publication and revision of the ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart which is the standard, reference global Geological Time Scale to include the ratified Commission decisions".[1]

Following on from Holmes, several A Geological Time Scale books were published in 1982,[60] 1989,[61] 2004,[62] 2008,[63] 2012,[64] 2016,[65] and 2020.[66] However, since 2013, the ICS has taken responsibility for producing and distributing the ICC citing the commercial nature, independent creation, and lack of oversight by the ICS on the prior published GTS versions (GTS books prior to 2013) although these versions were published in close association with the ICS.[2] Subsequent Geologic Time Scale books (2016[65] and 2020[66]) are commercial publications with no oversight from the ICS, and do not entirely conform to the chart produced by the ICS. The ICS produced GTS charts are versioned (year/month) beginning at v2013/01. At least one new version is published each year incorporating any changes ratified by the ICS since the prior version.

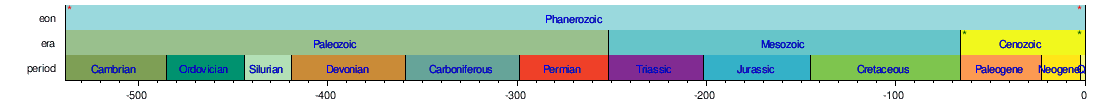

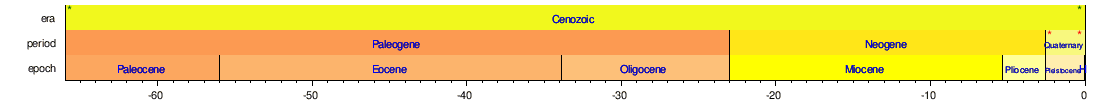

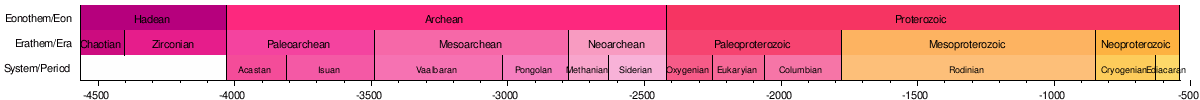

The following five timelines show the geologic time scale to scale. The first shows the entire time from the formation of Earth to the present, but this gives little space for the most recent eon. The second timeline shows an expanded view of the most recent eon. In a similar way, the most recent era is expanded in the third timeline, the most recent period is expanded in the fourth timeline, and the most recent epoch is expanded in the fifth timeline.

(Horizontal scale is millions of years for the above timelines; thousands of years for the timeline below)

Major proposed revisions to the ICC

[edit]Proposed Anthropocene Series/Epoch

[edit]First suggested in 2000,[67] the Anthropocene is a proposed epoch/series for the most recent time in Earth's history. While still informal, it is a widely used term to denote the present geologic time interval, in which many conditions and processes on Earth are profoundly altered by human impact.[68] The definition of the Anthropocene as a geologic time period rather than a geologic event remains controversial and difficult.[69][70][71][72]

In May 2019 the Anthropocene Working Group voted in favour of submitting a formal proposal to the ICS for the establishment of the Anthropocene Series/Epoch.[73] The formal proposal was completed and submitted to the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy in late 2023 for a section in Crawford Lake, Ontario, with heightened Plutonium levels corresponding to 1952 CE.[74] This proposal was rejected as a formal geologic epoch in early 2024, to be left instead as an "invaluable descriptor of human impact on the Earth system"[75]

Proposals for revisions to pre-Cryogenian timeline

[edit]Shields et al. 2021

[edit]The ICS Subcommission for Cryogenian Stratigraphy has outlined a template to improve the pre-Cryogenian geologic time scale based on the rock record to bring it in line with the post-Tonian geologic time scale.[4] This work assessed the geologic history of the currently defined eons and eras of the Precambrian,[note 2] and the proposals in the "Geological Time Scale" books 2004,[76] 2012,[5] and 2020.[77] Their recommend revisions[4] of the pre-Cryogenian geologic time scale were as below (changes from the current scale [v2023/09] are italicised). This suggestion was unanimously rejected by the International Subcommission for Precambrian Stratigraphy, based on scientific weaknesses.

- Three divisions of the Archean instead of four by dropping Eoarchean, and revisions to their geochronometric definition, along with the repositioning of the Siderian into the latest Neoarchean, and a potential Kratian division in the Neoarchean.

- Archean (4000–2450 Ma)

- Paleoarchean (4000–3500 Ma)

- Mesoarchean (3500–3000 Ma)

- Neoarchean (3000–2450 Ma)

- Kratian (no fixed time given, prior to the Siderian) – from Greek κράτος (krátos) 'strength'.

- Siderian (?–2450 Ma) – moved from Proterozoic to end of Archean, no start time given, base of Paleoproterozoic defines the end of the Siderian

- Archean (4000–2450 Ma)

- Refinement of geochronometric divisions of the Proterozoic, Paleoproterozoic, repositioning of the Statherian into the Mesoproterozoic, new Skourian period/system in the Paleoproterozoic, new Kleisian or Syndian period/system in the Neoproterozoic.

- Paleoproterozoic (2450–1800 Ma)

- Skourian (2450–2300 Ma) – from Greek σκουριά (skouriá) 'rust'.

- Rhyacian (2300–2050 Ma)

- Orosirian (2050–1800 Ma)

- Mesoproterozoic (1800–1000 Ma)

- Statherian (1800–1600 Ma)

- Calymmian (1600–1400 Ma)

- Ectasian (1400–1200 Ma)

- Stenian (1200–1000 Ma)

- Neoproterozoic (1000–538.8 Ma)[note 4]

- Kleisian or Syndian (1000–800 Ma) – respectively from Greek κλείσιμο (kleísimo) 'closure' and σύνδεση (sýndesi) 'connection'.

- Tonian (800–720 Ma)

- Cryogenian (720–635 Ma)

- Ediacaran (635–538.8 Ma)

- Paleoproterozoic (2450–1800 Ma)

Proposed pre-Cambrian timeline (Shield et al. 2021, ICS working group on pre-Cryogenian chronostratigraphy), shown to scale:[note 5]

ICC pre-Cambrian timeline (v2024/12, current as of January 2025[update]), shown to scale:

Van Kranendonk et al. 2012 (GTS2012)

[edit]The book, Geologic Time Scale 2012, was the last commercial publication of an international chronostratigraphic chart that was closely associated with the ICS and the Subcommission on Precambrian Stratigraphy.[2] It included a proposal to substantially revise the pre-Cryogenian time scale to reflect important events such as the formation of the Solar System and the Great Oxidation Event, among others, while at the same time maintaining most of the previous chronostratigraphic nomenclature for the pertinent time span.[78] As of April 2022[update] these proposed changes have not been accepted by the ICS. The proposed changes (changes from the current scale [v2023/09]) are italicised:

- Hadean Eon (4567–4030 Ma)

- Chaotian Era/Erathem (4567–4404 Ma) – the name alluding both to the mythological Chaos and the chaotic phase of planet formation.[64][79][80]

- Jack Hillsian or Zirconian Era/Erathem (4404–4030 Ma) – both names allude to the Jack Hills Greenstone Belt which provided the oldest mineral grains on Earth, zircons.[64][79]

- Archean Eon/Eonothem (4030–2420 Ma)

- Paleoarchean Era/Erathem (4030–3490 Ma)

- Acastan Period/System (4030–3810 Ma) – named after the Acasta Gneiss, one of the oldest preserved pieces of continental crust.[64][79]

- Isuan Period/System (3810–3490 Ma) – named after the Isua Greenstone Belt.[64]

- Mesoarchean Era/Erathem (3490–2780 Ma)

- Vaalbaran Period/System (3490–3020 Ma) – based on the names of the Kaapvaal (Southern Africa) and Pilbara (Western Australia) cratons, to reflect the growth of stable continental nuclei or proto-cratonic kernels.[64]

- Pongolan Period/System (3020–2780 Ma) – named after the Pongola Supergroup, in reference to the well preserved evidence of terrestrial microbial communities in those rocks.[64]

- Neoarchean Era/Erathem (2780–2420 Ma)

- Methanian Period/System (2780–2630 Ma) – named for the inferred predominance of methanotrophic prokaryotes[64]

- Siderian Period/System (2630–2420 Ma) – named for the voluminous banded iron formations formed within its duration.[64]

- Paleoarchean Era/Erathem (4030–3490 Ma)

- Proterozoic Eon/Eonothem (2420–538.8 Ma)[note 4]

- Paleoproterozoic Era/Erathem (2420–1780 Ma)

- Oxygenian Period/System (2420–2250 Ma) – named for displaying the first evidence for a global oxidising atmosphere.[64]

- Jatulian or Eukaryian Period/System (2250–2060 Ma) – names are respectively for the Lomagundi–Jatuli δ13C isotopic excursion event spanning its duration, and for the (proposed)[81][82] first fossil appearance of eukaryotes.[64]

- Columbian Period/System (2060–1780 Ma) – named after the supercontinent Columbia.[64]

- Mesoproterozoic Era/Erathem (1780–850 Ma)

- Paleoproterozoic Era/Erathem (2420–1780 Ma)

Proposed pre-Cambrian timeline (GTS2012), shown to scale:

ICC pre-Cambrian timeline (v2024/12, current as of January 2025[update]), shown to scale:

Table of geologic time

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

The following table summarises the major events and characteristics of the divisions making up the geologic time scale of Earth. This table is arranged with the most recent geologic periods at the top, and the oldest at the bottom. The height of each table entry does not correspond to the duration of each subdivision of time. As such, this table is not to scale and does not accurately represent the relative time-spans of each geochronologic unit. While the Phanerozoic Eon looks longer than the rest, it merely spans ~538.8 Ma (~11.8% of Earth's history), whilst the previous three eons[note 2] collectively span ~4,028.2 Ma (~88.2% of Earth's history). This bias toward the most recent eon is in part due to the relative lack of information about events that occurred during the first three eons compared to the current eon (the Phanerozoic).[4][83] The use of subseries/subepochs has been ratified by the ICS.[15]

While some regional terms are still in use,[5] the table of geologic time conforms to the nomenclature, ages, and colour codes set forth by the International Commission on Stratigraphy in the official International Chronostratigraphic Chart.[1][84] The International Commission on Stratigraphy also provide an online interactive version of this chart. The interactive version is based on a service delivering a machine-readable Resource Description Framework/Web Ontology Language representation of the time scale, which is available through the Commission for the Management and Application of Geoscience Information GeoSciML project as a service[85] and at a SPARQL end-point.[86][87]

| Eonothem/ Eon |

Erathem/ Era |

System/ Period |

Series/ Epoch |

Stage/ Age |

Major events | Start, million years ago [note 6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phanerozoic | Cenozoic [note 3] |

Quaternary | Holocene | Meghalayan | 4.2-kiloyear event, Austronesian expansion, increasing industrial CO2. | 0.0042 * |

| Northgrippian | 8.2-kiloyear event, Holocene climatic optimum. Sea level flooding of Doggerland and Sundaland. Sahara becomes a desert. End of Stone Age and start of recorded history. Humans finally expand into the Arctic Archipelago and Greenland. | 0.0082 * | ||||

| Greenlandian | Climate stabilises. Current interglacial and Holocene extinction begins. Agriculture begins. Humans spread across the wet Sahara and Arabia, the Extreme North, and the Americas (mainland and the Caribbean). | 0.0117 * | ||||

| Pleistocene | Upper/Late ('Tarantian') | Eemian interglacial, last glacial period, ending with Younger Dryas. Toba eruption. Pleistocene megafauna (including the last terror birds) extinction. Humans expand into Near Oceania and the Americas. | 0.129 | |||

| Chibanian | Mid-Pleistocene Transition occurs, high amplitude 100 ka glacial cycles. Rise of Homo sapiens. | 0.774 * | ||||

| Calabrian | Further cooling of the climate. Giant terror birds go extinct. Spread of Homo erectus across Afro-Eurasia. | 1.8 * | ||||

| Gelasian | Start of Quaternary glaciations and unstable climate.[88] Rise of the Pleistocene megafauna and Homo habilis. | 2.58 * | ||||

| Neogene | Pliocene | Piacenzian | Greenland ice sheet develops[89] as the cold slowly intensifies towards the Pleistocene. Atmospheric O2 and CO2 content reaches present-day levels while landmasses also reach their current locations (e.g. the Isthmus of Panama joins the North and South Americas, while allowing a faunal interchange). The last non-marsupial metatherians go extinct. Australopithecus common in East Africa; Stone Age begins.[90] | 3.6 * | ||

| Zanclean | Zanclean flooding of the Mediterranean Basin. Cooling climate continues from the Miocene. First equines and elephantines. Ardipithecus in Africa.[90] | 5.333 * | ||||

| Miocene | Messinian | Messinian Event with hypersaline lakes in empty Mediterranean Basin. Sahara desert formation begins. Moderate icehouse climate, punctuated by ice ages and re-establishment of East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Choristoderes, the last non-crocodilian crocodylomorphs and creodonts go extinct. After separating from gorilla ancestors, chimpanzee and human ancestors gradually separate; Sahelanthropus and Orrorin in Africa. | 7.246 * | |||

| Tortonian | 11.63 * | |||||

| Serravallian | Middle Miocene climate optimum temporarily provides a warm climate.[91] Extinctions in middle Miocene disruption, decreasing shark diversity. First hippos. Ancestor of great apes. | 13.82 * | ||||

| Langhian | 15.98 * | |||||

| Burdigalian | Orogeny in Northern Hemisphere. Start of Kaikoura Orogeny forming Southern Alps in New Zealand. Widespread forests slowly draw in massive amounts of CO2, gradually lowering the level of atmospheric CO2 from 650 ppmv down to around 100 ppmv during the Miocene.[92][note 7] Modern bird and mammal families become recognizable. The last of the primitive whales go extinct. Grasses become ubiquitous. Ancestor of apes, including humans.[93][94] Afro-Arabia collides with Eurasia, fully forming the Alpide Belt and closing the Tethys Ocean, while allowing a faunal interchange. At the same time, Afro-Arabia splits into Africa and West Asia. | 20.45 | ||||

| Aquitanian | 23.04 * | |||||

| Paleogene | Oligocene | Chattian | Grande Coupure extinction. Start of widespread Antarctic glaciation.[95] Rapid evolution and diversification of fauna, especially mammals (e.g. first macropods and seals). Major evolution and dispersal of modern types of flowering plants. Cimolestans, miacoids and condylarths go extinct. First neocetes (modern, fully aquatic whales) appear. | 27.3 * | ||

| Rupelian | 33.9 * | |||||

| Eocene | Priabonian | Moderate, cooling climate. Archaic mammals (e.g. creodonts, miacoids, "condylarths" etc.) flourish and continue to develop during the epoch. Appearance of several "modern" mammal families. Primitive whales and sea cows diversify after returning to water. Birds continue to diversify. First kelp, diprotodonts, bears and simians. The multituberculates and leptictidans go extinct by the end of the epoch. Reglaciation of Antarctica and formation of its ice cap; End of Laramide and Sevier Orogenies of the Rocky Mountains in North America. Hellenic Orogeny begins in Greece and Aegean Sea. | 37.71 * | |||

| Bartonian | 41.03 | |||||

| Lutetian | 48.07 * | |||||

| Ypresian | Two transient events of global warming (PETM and ETM-2) and warming climate until the Eocene Climatic Optimum. The Azolla event decreased CO2 levels from 3500 ppm to 650 ppm, setting the stage for a long period of cooling.[92][note 7] Greater India collides with Eurasia and starts Himalayan Orogeny (allowing a biotic interchange) while Eurasia completely separates from North America, creating the North Atlantic Ocean. Maritime Southeast Asia diverges from the rest of Eurasia. First passerines, ruminants, pangolins, bats and true primates. | 56 * | ||||

| Paleocene | Thanetian | Starts with Chicxulub impact and the K–Pg extinction event, wiping out all non-avian dinosaurs and pterosaurs, most marine reptiles, many other vertebrates (e.g. many Laurasian metatherians), most cephalopods (only Nautilidae and Coleoidea survived) and many other invertebrates. Climate tropical. Mammals and birds (avians) diversify rapidly into a number of lineages following the extinction event (while the marine revolution stops). Multituberculates and the first rodents widespread. First large birds (e.g. ratites and terror birds) and mammals (up to bear or small hippo size). Alpine orogeny in Europe and Asia begins. First proboscideans and plesiadapiformes (stem primates) appear. Some marsupials migrate to Australia. | 59.24 * | |||

| Selandian | 61.66 * | |||||

| Danian | 66 * | |||||

| Mesozoic | Cretaceous | Upper/Late | Maastrichtian | Flowering plants proliferate (after developing many features since the Carboniferous), along with new types of insects, while other seed plants (gymnosperms and seed ferns) decline. More modern teleost fish begin to appear. Ammonoids, belemnites, rudist bivalves, sea urchins and sponges all common. Many new types of dinosaurs (e.g. tyrannosaurs, titanosaurs, hadrosaurs, and ceratopsids) evolve on land, while crocodilians appear in water and probably cause the last temnospondyls to die out; and mosasaurs and modern types of sharks appear in the sea. The revolution started by marine reptiles and sharks reaches its peak, though ichthyosaurs vanish a few million years after being heavily reduced at the Bonarelli Event. Toothed and toothless avian birds coexist with pterosaurs. Modern monotremes, metatherian (including marsupials, who migrate to South America) and eutherian (including placentals, leptictidans and cimolestans) mammals appear while the last non-mammalian cynodonts die out. First terrestrial crabs. Many snails become terrestrial. Further breakup of Gondwana creates South America, Afro-Arabia, Antarctica, Oceania, Madagascar, Greater India, and the South Atlantic, Indian and Antarctic Oceans and the islands of the Indian (and some of the Atlantic) Ocean. Beginning of Laramide and Sevier Orogenies of the Rocky Mountains. Atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide levels similar to present day. Acritarchs disappear. Climate initially warm, but later it cools. | 72.2 ± 0.2 * | |

| Campanian | 83.6 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Santonian | 85.7 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Coniacian | 89.8 ± 0.3 * | |||||

| Turonian | 93.9 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Cenomanian | 100.5 ± 0.1 * | |||||

| Lower/Early | Albian | ~113.2 ± 0.3 * | ||||

| Aptian | ~121.4 ± 0.6 | |||||

| Barremian | ~125.77 * | |||||

| Hauterivian | ~132.6 ± 0.6 * | |||||

| Valanginian | ~137.05 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Berriasian | ~143.1 ± 0.6 | |||||

| Jurassic | Upper/Late | Tithonian | Climate becomes humid again. Gymnosperms (especially conifers, cycads and cycadeoids) and ferns common. Dinosaurs, including sauropods, carnosaurs, stegosaurs and coelurosaurs, become the dominant land vertebrates. Mammals diversify into shuotheriids, australosphenidans, eutriconodonts, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, dryolestids and boreosphenidans but mostly remain small. First birds, lizards, snakes and turtles. First brown algae, rays, shrimps, crabs and lobsters. Parvipelvian ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs diverse. Rhynchocephalians throughout the world. Bivalves, ammonoids and belemnites abundant. Sea urchins very common, along with crinoids, starfish, sponges, and terebratulid and rhynchonellid brachiopods. Breakup of Pangaea into Laurasia and Gondwana, with the latter also breaking into two main parts; the Pacific and Arctic Oceans form. Tethys Ocean forms. Nevadan orogeny in North America. Rangitata and Cimmerian orogenies taper off. Atmospheric CO2 levels 3–4 times the present-day levels (1200–1500 ppmv, compared to today's 400 ppmv[92][note 7]). Crocodylomorphs (last pseudosuchians) seek out an aquatic lifestyle. Mesozoic marine revolution continues from late Triassic. Tentaculitans disappear. | 149.2 ± 0.7 | ||

| Kimmeridgian | 154.8 ± 0.8 * | |||||

| Oxfordian | 161.5 ± 1.0 | |||||

| Middle | Callovian | 165.3 ± 1.1 | ||||

| Bathonian | 168.2 ± 1.2 * | |||||

| Bajocian | 170.9 ± 0.8 * | |||||

| Aalenian | 174.7 ± 0.8 * | |||||

| Lower/Early | Toarcian | 184.2 ± 0.3 * | ||||

| Pliensbachian | 192.9 ± 0.3 * | |||||

| Sinemurian | 199.5 ± 0.3 * | |||||

| Hettangian | 201.4 ± 0.2 * | |||||

| Triassic | Upper/Late | Rhaetian | Archosaurs dominant on land as pseudosuchians and in the air as pterosaurs. Dinosaurs also arise from bipedal archosaurs. Ichthyosaurs and nothosaurs (a group of sauropterygians) dominate large marine fauna. Cynodonts become smaller and nocturnal, eventually becoming the first true mammals, while other remaining synapsids die out. Rhynchosaurs (archosaur relatives) also common. Seed ferns called Dicroidium remained common in Gondwana, before being replaced by advanced gymnosperms. Many large aquatic temnospondyl amphibians. Ceratitidan ammonoids extremely common. Modern corals and teleost fish appear, as do many modern insect orders and suborders. First starfish. Andean Orogeny in South America. Cimmerian Orogeny in Asia. Rangitata Orogeny begins in New Zealand. Hunter-Bowen Orogeny in Northern Australia, Queensland and New South Wales ends, (c. 260–225 Ma). Carnian pluvial event occurs around 234–232 Ma, allowing the first dinosaurs and lepidosaurs (including rhynchocephalians) to radiate. Triassic–Jurassic extinction event occurs 201 Ma, wiping out all conodonts and the last parareptiles, many marine reptiles (e.g. all sauropterygians except plesiosaurs and all ichthyosaurs except parvipelvians), all crocopodans except crocodylomorphs, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs, and many ammonoids (including the whole Ceratitida), bivalves, brachiopods, corals and sponges. First diatoms.[96] | ~205.7 | ||

| Norian | ~227.3 | |||||

| Carnian | ~237 * | |||||

| Middle | Ladinian | ~241.464 * | ||||

| Anisian | 246.7 | |||||

| Lower/Early | Olenekian | 249.9 | ||||

| Induan | 251.902 ± 0.024 * | |||||

| Paleozoic | Permian | Lopingian | Changhsingian | Landmasses unite into supercontinent Pangaea, creating the Urals, Ouachitas and Appalachians, among other mountain ranges (the superocean Panthalassa or Proto-Pacific also forms). End of Permo-Carboniferous glaciation. Hot and dry climate. A possible drop in oxygen levels. Synapsids (pelycosaurs and therapsids) become widespread and dominant, while parareptiles and temnospondyl amphibians remain common, with the latter probably giving rise to modern amphibians in this period. In the mid-Permian, lycophytes are heavily replaced by ferns and seed plants. Beetles and flies evolve. The very large arthropods and non-tetrapod tetrapodomorphs go extinct. Marine life flourishes in warm shallow reefs; productid and spiriferid brachiopods, bivalves, forams, ammonoids (including goniatites), and orthoceridans all abundant. Crown reptiles arise from earlier diapsids, and split into the ancestors of lepidosaurs, kuehneosaurids, choristoderes, archosaurs, testudinatans, ichthyosaurs, thalattosaurs, and sauropterygians. Cynodonts evolve from larger therapsids. Olson's Extinction (273 Ma), End-Capitanian extinction (260 Ma), and Permian–Triassic extinction event (252 Ma) occur one after another: more than 80% of life on Earth becomes extinct in the lattermost, including most retarian plankton, corals (Tabulata and Rugosa die out fully), brachiopods, bryozoans, gastropods, ammonoids (the goniatites die off fully), insects, parareptiles, synapsids, amphibians, and crinoids (only articulates survived), and all eurypterids, trilobites, graptolites, hyoliths, edrioasteroid crinozoans, blastoids and acanthodians. Ouachita and Innuitian orogenies in North America. Uralian orogeny in Europe/Asia tapers off. Altaid orogeny in Asia. Hunter-Bowen Orogeny on Australian continent begins (c. 260–225 Ma), forming the New England Fold Belt. | 254.14 ± 0.07 * | |

| Wuchiapingian | 259.51 ± 0.21 * | |||||

| Guadalupian | Capitanian | 264.28 ± 0.16 * | ||||

| Wordian | 266.9 ± 0.4 * | |||||

| Roadian | 274.4 ± 0.4 * | |||||

| Cisuralian | Kungurian | 283.3 ± 0.4 | ||||

| Artinskian | 290.1 ± 0.26 * | |||||

| Sakmarian | 293.52 ± 0.17 * | |||||

| Asselian | 298.9 ± 0.15 * | |||||

| Carboniferous [note 8] |

Pennsylvanian [note 9] |

Gzhelian | Winged insects radiate suddenly; some (esp. Protodonata and Palaeodictyoptera) of them as well as some millipedes and scorpions become very large. First coal forests (scale trees, ferns, club trees, giant horsetails, Cordaites, etc.). Higher atmospheric oxygen levels. Ice Age continues to the Early Permian. Goniatites, brachiopods, bryozoa, bivalves, and corals plentiful in the seas and oceans. First woodlice. Testate forams proliferate. Euramerica collides with Gondwana and Siberia-Kazakhstania, the latter of which forms Laurasia and the Uralian orogeny. Variscan orogeny continues (these collisions created orogenies, and ultimately Pangaea). Amphibians (e.g. temnospondyls) spread in Euramerica, with some becoming the first amniotes. Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse occurs, initiating a dry climate which favors amniotes over amphibians. Amniotes diversify rapidly into synapsids, parareptiles, cotylosaurs, protorothyridids and diapsids. Rhizodonts remained common before they died out by the end of the period. First sharks. | 303.7 | ||

| Kasimovian | 307 ± 0.1 | |||||

| Moscovian | 315.2 ± 0.2 | |||||

| Bashkirian | 323.4 * | |||||

| Mississippian [note 9] |

Serpukhovian | Large lycopodian primitive trees flourish and amphibious eurypterids live amid coal-forming coastal swamps, radiating significantly one last time. First gymnosperms. First holometabolous, paraneopteran, polyneopteran, odonatopteran and ephemeropteran insects and first barnacles. First five-digited tetrapods (amphibians) and land snails. In the oceans, bony and cartilaginous fishes are dominant and diverse; echinoderms (especially crinoids and blastoids) abundant. Corals, bryozoans, orthoceridans, goniatites and brachiopods (Productida, Spiriferida, etc.) recover and become very common again, but trilobites and nautiloids decline. Glaciation in East Gondwana continues from Late Devonian. Tuhua Orogeny in New Zealand tapers off. Some lobe finned fish called rhizodonts become abundant and dominant in freshwaters. Siberia collides with a different small continent, Kazakhstania. | 330.3 ± 0.4 | |||

| Viséan | 346.7 ± 0.4 * | |||||

| Tournaisian | 358.86 ± 0.19 * | |||||

| Devonian | Upper/Late | Famennian | Paleo-Tethys continues to open as the Armorican Terrane Assemblage (ATA) drifts north and Annamia-South China moves away from Gondwana.[97][98] Rheic Ocean closes as ATA collides with Laurussia beginning the Variscan orogeny. Other orogenies: Antler, Ellesmerian, and Acadian (Laurussia); Achalian (Argentina); Tabberabberan/Lachlan (Australia); Ross (Antarctica); Kazakh (Kazakhstania).[97] Period of high sea-levels, greenhouse conditions but decreasing atmospheric CO2 levels and slowly cooling climate with glaciations towards end.[99] Vascular plants increase in size, develop large root systems and spread to upland areas. First forests, seed plants, and modern soil orders appear (alfisols and ultisols).[99] Growth of massive reef systems. Major radiation of jawed fish with appearance of ray-finned, lobe-finned, and cartilaginous fish. Appearance of tetrapods (evolved from lobe-finned fish). Early amphibians move on to land. First ammonoids.[100] Emplacement of the Viley and Pripyat–Dniepr–Donets large igneous provinces coincide with global marine anoxic events and the Kellwasser (c. 372 Ma) and Hangenberg (c. 359 Ma) mass extinctions.[99] Kellwasser extinction: c. 20% of families and c. 50% of genera of marine invertebrates lost. Tabulate coral and stromatoporoid reef ecosystems wiped out. Loss of placoderms and many groups of jawless fish. Hangenberg extinction: loss of c. 16% of marine families and c. 21% of marine genera, including ammonoids, ostracods and sharks.[99][101] | 372.15 ± 0.46 * | ||

| Frasnian | 382.31 ± 1.36 * | |||||

| Middle | Givetian | 387.95 ± 1.04 * | ||||

| Eifelian | 393.47 ± 0.99 * | |||||

| Lower/Early | Emsian | 410.62 ± 1.95 * | ||||

| Pragian | 413.02 ± 1.91 * | |||||

| Lochkovian | 419.62 ± 1.36 * | |||||

| Silurian | Pridoli | Laurentia and Avalonia-Baltica collide as Iapetus Ocean closes, Caledonian-Scandian orogeny, and formation of Laurussia. Other orogenies: Salinic (Appalachians); Famatinian (South America) tapers off; Lachlan (Australia).[97][102] Series of microcontinents and North China separate opening Paleo-Tethys and closing Paleoasian Ocean.[102] Rheic Ocean widens between Gondwana and Laurussia. Siberia drifts north of equator.[97] Temperatures increase as Hirnantian glaciation ends. Sea levels rise. Deposition of black shales, North Africa and Arabia, major hydrocarbon source rocks.[97] Fluctuating climate with glacial advances results in changing ocean conditions causes extinction events, followed by ecological recoveries.[103] Widespread evaporite deposition and hothouse climate by late Silurian.[100][104] After end-Ordovician mass extinction, major radiation of graptolites, bivalves, gastropods, nautiloids, brachiopods, and crinoids. Increase in trilobites, but never fully recover. Corals and stromatoporiods diversify to produce large reefs. Proliferation of eurypterid arthropods. Earliest jawed fish (acanthodians). Appearance of ostracoderms. Appearance of vascular plants. First land animals including myriapods. First freshwater fish.[100] | 422.7 ± 1.6 * | |||

| Ludlow | Ludfordian | 425 ± 1.5 * | ||||

| Gorstian | 426.7 ± 1.5 * | |||||

| Wenlock | Homerian | 430.6 ± 1.3 * | ||||

| Sheinwoodian | 432.9 ± 1.2 * | |||||

| Llandovery | Telychian | 438.6 ± 1.0 * | ||||

| Aeronian | 440.5 ± 1.0 * | |||||

| Rhuddanian | 443.1 ± 0.9 * | |||||

| Ordovician | Upper/Late | Hirnantian | Most continents lay in equatorial regions. Gondwana stretched to south pole. Panthalassic Ocean covered northern hemisphere. Avalonia rifted from Gondwana closing Iapetus Ocean in front, opening Rheic Ocean behind. South China close to Gondwana; North China between Siberia and Gondwana. Orogenies: Famatinian (South America); Benambran (Australia); Taconic (Laurentia). Baltica and Siberia drift north.[97] Early greenhouse climate, cooling to icehouse conditions during Hirnantian Ice Age. Increase in atmospheric O2.[105] Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event, major increase in new genera e.g. brachiopods, trilobites, corals, echinoderms, bryozoans, gastropods, bivalves, nautiloids, graptolites, and conodonts. Very high sea levels expand shallow continental seas, increase range of ecological niches.[106] Modern marine ecosystems established.[105] Earliest jawless fish. Tabulate corals and stromatoporoids dominant reef builders. Nautiloids main predators.[100] Appearance of eurypterids and asteroids. Spread of early land plants.[105] Late Ordovician Mass Extinction, loss of ~85 % of marine invertebrate species. Two pulses: first with onset of glaciation affects tropical fauna; second at end of ice age, warming climate impacts cool water species.[100] Drastic reduction in trilobite, brachiopod, graptolite, echinoderm, conodont, coral, and chitinozoan genera.[106] | 445.2 ± 0.9 * | ||

| Katian | 452.8 ± 0.7 * | |||||

| Sandbian | 458.2 ± 0.7 * | |||||

| Middle | Darriwilian | 469.4 ± 0.9 * | ||||

| Dapingian | 471.3 ± 1.4 * | |||||

| Lower/Early | Floian (formerly Arenig) |

477.1 ± 1.2 * | ||||

| Tremadocian | 486.85 ± 1.5 * | |||||

| Cambrian | Furongian | Stage 10 | Gondwana stretched from the south pole to equator, separated from Laurentia and Baltica by the Iapetus Ocean. Siberia lay close to the equator, north of Baltica; North and South China close to equatorial Gondwana. Orogenies: Cadomian (N.Africa/southern Europe); Kuunga (central Gondwana); Famatinian orogeny (South America); Delamerian (Australia).[107] Greenhouse climate. High atmospheric CO2 levels. Atmospheric oxygen levels rose with increase in photosynthesising organisms.[108] Early aragonite seas replaced by mixed aragonite-calcite seas with many animals developing CaCO3 skeletons.[109] Rapid diversification of animals (Cambrian Explosion), most modern animal phyla appear, e.g. arthropods; molluscs; annelids; echinoderms; bryozoa; priapulids; brachiopods; hemichordates; and, chordates. Radiations of small shelly fossils.[110] Giant anomalocarids (arthropods) dominant predators. Increase in bioturbation and grazing led to decline in stromatolites.[100] Varying oxygen levels in oceans led to series of extinction events followed by radiations, including: earliest Cambrian loss of the Ediacaran acritarchs; end-Botomian extinction, linked to the Kalkarindji Large Igneous Province eruptions (c. 514 Ma) with loss of archaeocyathids (early Cambrian reef builders) and hyoliths; and, end-Cambrian reduction in trilobite diversity.[108][111][100] Many fossil lagerstätten, including Burgess Shale and Chengjiang Formation, formed by rapid burial in anoxic conditions.[108] | ~491 | ||

| Jiangshanian | ~494.2 * | |||||

| Paibian | ~497 * | |||||

| Miaolingian | Guzhangian | ~500.5 * | ||||

| Drumian | ~504.5 * | |||||

| Wuliuan | ~506.5 | |||||

| Series 2 | Stage 4 | ~514.5 | ||||

| Stage 3 | ~521 | |||||

| Terreneuvian | Stage 2 | ~529 | ||||

| Fortunian | 538.8 ± 0.6 * | |||||

| Proterozoic | Neoproterozoic | Ediacaran | Good fossils of primitive animals. Ediacaran biota flourish worldwide in seas, possibly appearing after an explosion, possibly caused by a large-scale oxidation event.[112] First vendozoans (unknown affinity among animals), cnidarians and bilaterians. Enigmatic vendozoans include many soft-jellied creatures shaped like bags, disks, or quilts (like Dickinsonia). Simple trace fossils of possible worm-like Trichophycus, etc. Taconic Orogeny in North America. Aravalli Range orogeny in Indian subcontinent. Beginning of Pan-African Orogeny, leading to the formation of the short-lived Ediacaran supercontinent Pannotia, which by the end of the period breaks up into Laurentia, Baltica, Siberia and Gondwana. Petermann Orogeny forms on Australian continent. Beardmore Orogeny in Antarctica, 633–620 Ma. Ozone layer forms. An increase in oceanic mineral levels. | ~635 * | ||

| Cryogenian | Possible "Snowball Earth" period. Fossils still rare. Late Ruker / Nimrod Orogeny in Antarctica tapers off. First uncontroversial animal fossils. First hypothetical terrestrial fungi[113] and streptophyta.[114] | ~720 | ||||

| Tonian | Final assembly of Rodinia supercontinent occurs in early Tonian, with breakup beginning c. 800 Ma. Sveconorwegian orogeny ends. Grenville Orogeny tapers off in North America. Lake Ruker / Nimrod Orogeny in Antarctica, 1,000 ± 150 Ma. Edmundian Orogeny (c. 920–850 Ma), Gascoyne Complex, Western Australia. Deposition of Adelaide Superbasin and Centralian Superbasin begins on Australian continent. First hypothetical animals (from holozoans) and terrestrial algal mats. Many endosymbiotic events concerning red and green algae occur, transferring plastids to ochrophyta (e.g. diatoms, brown algae), dinoflagellates, cryptophyta, haptophyta, and euglenids (the events may have begun in the Mesoproterozoic)[115] while the first retarians (e.g. forams) also appear: eukaryotes diversify rapidly, including algal, eukaryovoric and biomineralised forms. Trace fossils of simple multi-celled eukaryotes. Neoproterozoic oxygenation event (NOE), 850–540 Ma.[116] | 1000 [note 10] | ||||

| Mesoproterozoic | Stenian | Narrow highly metamorphic belts due to orogeny as Rodinia forms, surrounded by the Pan-African Ocean. Sveconorwegian orogeny starts. Late Ruker / Nimrod Orogeny in Antarctica possibly begins. Musgrave Orogeny (c. 1,080–), Musgrave Block, Central Australia. Stromatolites decline as algae proliferate. | 1200 [note 10] | |||

| Ectasian | Platform covers continue to expand. Algal colonies in the seas. Grenville Orogeny in North America. Columbia breaks up. | 1400 [note 10] | ||||

| Calymmian | Platform covers expand. Barramundi Orogeny, McArthur Basin, Northern Australia, and Isan Orogeny, c. 1,600 Ma, Mount Isa Block, Queensland. First archaeplastidans (the first eukaryotes with plastids from cyanobacteria; e.g. red and green algae) and opisthokonts (giving rise to the first fungi and holozoans). Acritarchs (remains of marine algae possibly) start appearing in the fossil record. | 1600 [note 10] | ||||

| Paleoproterozoic | Statherian | First uncontroversial eukaryotes: protists with nuclei and endomembrane system. Columbia forms as the second undisputed earliest supercontinent. Kimban Orogeny in Australian continent ends. Yapungku Orogeny on Yilgarn craton, in Western Australia. Mangaroon Orogeny, 1,680–1,620 Ma, on the Gascoyne Complex in Western Australia. Kararan Orogeny (1,650 Ma), Gawler craton, South Australia. Oxygen levels drop again. | 1800 [note 10] | |||

| Orosirian | The atmosphere becomes much more oxygenic while more cyanobacterial stromatolites appear. Vredefort and Sudbury Basin asteroid impacts. Much orogeny. Penokean and Trans-Hudsonian Orogenies in North America. Early Ruker Orogeny in Antarctica, 2,000–1,700 Ma. Glenburgh Orogeny, Glenburgh Terrane, Australian continent c. 2,005–1,920 Ma. Kimban Orogeny, Gawler craton in Australian continent begins. | 2050 [note 10] | ||||

| Rhyacian | Bushveld Igneous Complex forms. Huronian glaciation. First hypothetical eukaryotes. Multicellular Francevillian biota. Kenorland disassembles. | 2300 [note 10] | ||||

| Siderian | Great Oxidation Event (due to cyanobacteria) increases oxygen. Sleaford Orogeny on Australian continent, Gawler craton 2,440–2,420 Ma. | 2500 [note 10] | ||||

| Archean | Neoarchean | Stabilization of most modern cratons; possible mantle overturn event. Insell Orogeny, 2,650 ± 150 Ma. Abitibi greenstone belt in present-day Ontario and Quebec begins to form, stabilises by 2,600 Ma. First uncontroversial supercontinent, Kenorland, and first terrestrial prokaryotes. | 2800 [note 10] | |||

| Mesoarchean | Stromatolites (probably colonial phototrophic bacteria, like cyanobacteria). Oldest macrofossils. Humboldt Orogeny in Antarctica. Blake River Megacaldera Complex begins to form in present-day Ontario and Quebec, ends by roughly 2,696 Ma. | 3200 [note 10] | ||||

| Paleoarchean | Prokaryotic archaea (e.g. methanogens) and bacteria (e.g. cyanobacteria) diversify rapidly, along with early viruses. First known phototrophic bacteria. Oldest definitive microfossils. First microbial mats, stromatolites and MISS. Oldest cratons on Earth (such as the Canadian Shield and the Pilbara Craton) may have formed during this period.[note 11] Rayner Orogeny in Antarctica. | 3600 [note 10] | ||||

| Eoarchean | First uncontroversial living organisms: at first protocells with RNA-based genes around 4000 Ma, after which true cells (prokaryotes) evolve along with proteins and DNA-based genes around 3800 Ma. The end of the Late Heavy Bombardment. Napier Orogeny in Antarctica, 4,000 ± 200 Ma. | 4031 [note 10] | ||||

| Hadean | Formation of protolith of the oldest known rock (Acasta Gneiss) c. 4,031 to 3,580 Ma.[117][118] Possible first appearance of plate tectonics. First hypothetical life forms. End of the Early Bombardment Phase. Oldest known mineral (Zircon, 4,404 ± 8 Ma).[119] Asteroids and comets bring water to Earth, forming the first oceans. Formation of Moon (4,510 Ma), probably from a giant impact. Formation of Earth (4,543 to 4,540 Ma) | 4567 ± 0.16 [note 10] | ||||

Extraterrestrial geologic time scales

[edit]Some other planets and satellites in the Solar System have sufficiently rigid structures to have preserved records of their own histories, for example, Venus, Mars and the Earth's Moon. Dominantly fluid planets, such as the giant planets, do not comparably preserve their history. Apart from the Late Heavy Bombardment, events on other planets probably had little direct influence on the Earth, and events on Earth had correspondingly little effect on those planets. Construction of a time scale that links the planets is, therefore, of only limited relevance to the Earth's time scale, except in a Solar System context. The existence, timing, and terrestrial effects of the Late Heavy Bombardment are still a matter of debate.[note 12]

Lunar (selenological) time scale

[edit]The geologic history of Earth's Moon has been divided into a time scale based on geomorphological markers, namely impact cratering, volcanism, and erosion. This process of dividing the Moon's history in this manner means that the time scale boundaries do not imply fundamental changes in geological processes, unlike Earth's geologic time scale. Five geologic systems/periods (Pre-Nectarian, Nectarian, Imbrian, Eratosthenian, Copernican), with the Imbrian divided into two series/epochs (Early and Late) were defined in the latest Lunar geologic time scale.[120] The Moon is unique in the Solar System in that it is the only other body from which humans have rock samples with a known geological context.

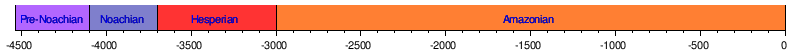

Martian geologic time scale

[edit]The geological history of Mars has been divided into two alternate time scales. The first time scale for Mars was developed by studying the impact crater densities on the Martian surface. Through this method four periods have been defined, the Pre-Noachian (~4,500–4,100 Ma), Noachian (~4,100–3,700 Ma), Hesperian (~3,700–3,000 Ma), and Amazonian (~3,000 Ma to present).[121][122]

Epochs:

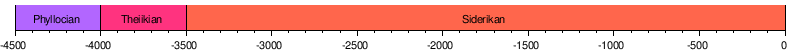

A second time scale based on mineral alteration observed by the OMEGA spectrometer on board the Mars Express. Using this method, three periods were defined, the Phyllocian (~4,500–4,000 Ma), Theiikian (~4,000–3,500 Ma), and Siderikian (~3,500 Ma to present).[123]

See also

[edit]- Age of the Earth

- Cosmic calendar

- Deep time

- Evolutionary history of life

- Formation and evolution of the Solar System

- Geological history of Earth

- Geology of Mars

- Geon (geology)

- History of Earth

- History of geology

- History of paleontology

- List of fossil sites

- List of geochronologic names

- Lunar geologic timescale

- Martian geologic timescale

- Natural history

- New Zealand geologic time scale

- Prehistoric life

- Timeline of the Big Bang

- Timeline of evolution

- Timeline of the geologic history of the United States

- Timeline of human evolution

- Timeline of natural history

- Timeline of paleontology

Notes

[edit]- ^ Time spans of geologic time units vary broadly, and there is no numeric limitation on the time span they can represent. They are limited by the time span of the higher rank unit they belong to, and to the chronostratigraphic boundaries they are defined by.

- ^ a b c Precambrian or pre-Cambrian is an informal geological term for time before the Cambrian period

- ^ a b The Tertiary is a now obsolete geologic system/period spanning from 66 Ma to 2.6 Ma. It has no exact equivalent in the modern ICC, but is approximately equivalent to the merged Palaeogene and Neogene systems/periods.[20][21]

- ^ a b Geochronometric date for the Ediacaran has been adjusted to reflect ICC v2023/09 as the formal definition for the base of the Cambrian has not changed.

- ^ Kratian time span is not given in the article. It lies within the Neoarchean, and prior to the Siderian. The position shown here is an arbitrary division.

- ^ The dates and uncertainties quoted are according to the International Commission on Stratigraphy International Chronostratigraphic chart (v2024/12). An * indicates boundaries where a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point has been internationally agreed.

- ^ a b c For more information on this, see Atmosphere of Earth#Evolution of Earth's atmosphere, Carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere, and climate change. Specific graphs of reconstructed CO2 levels over the past ~550, 65, and 5 million years can be seen at File:Phanerozoic Carbon Dioxide.png, File:65 Myr Climate Change.png, File:Five Myr Climate Change.png, respectively.

- ^ The Mississippian and Pennsylvanian are official sub-systems/sub-periods.

- ^ a b This is divided into Lower/Early, Middle, and Upper/Late series/epochs

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Defined by absolute age (Global Standard Stratigraphic Age).

- ^ The age of the oldest measurable craton, or continental crust, is dated to 3,600–3,800 Ma.

- ^ Not enough is known about extra-solar planets for worthwhile speculation.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Statues & Guidelines". International Commission on Stratigraphy. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. December 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Special Publications, Geological Society of London. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. S2CID 130092094.

- ^ a b c d e Shields, Graham A.; Strachan, Robin A.; Porter, Susannah M.; Halverson, Galen P.; Macdonald, Francis A.; Plumb, Kenneth A.; de Alvarenga, Carlos J.; Banerjee, Dhiraj M.; Bekker, Andrey; Bleeker, Wouter; Brasier, Alexander (2022). "A template for an improved rock-based subdivision of the pre-Cryogenian timescale". Journal of the Geological Society. 179 (1): jgs2020–222. Bibcode:2022JGSoc.179..222S. doi:10.1144/jgs2020-222. ISSN 0016-7649. S2CID 236285974.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Van Kranendonk, Martin J.; Altermann, Wladyslaw; Beard, Brian L.; Hoffman, Paul F.; Johnson, Clark M.; Kasting, James F.; Melezhik, Victor A.; Nutman, Allen P. (2012), "A Chronostratigraphic Division of the Precambrian", The Geologic Time Scale, Elsevier, pp. 299–392, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-59425-9.00016-0, ISBN 978-0-444-59425-9, retrieved 5 April 2022

- ^ "International Commission on Stratigraphy - Stratigraphic Guide - Chapter 9. Chronostratigraphic Units". stratigraphy.org. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Boggs, Sam (2011). Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy (5th ed.). Boston, Munich: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-321-74576-7.