Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

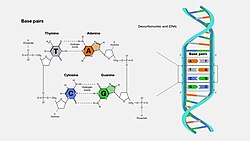

Base pair

View on Wikipedia

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA. Dictated by specific hydrogen bonding patterns, "Watson–Crick" (or "Watson–Crick–Franklin") base pairs (guanine–cytosine and adenine–thymine/uracil)[1] allow the DNA helix to maintain a regular helical structure that is subtly dependent on its nucleotide sequence.[2] The complementary nature of this based-paired structure provides a redundant copy of the genetic information encoded within each strand of DNA. The regular structure and data redundancy provided by the DNA double helix make DNA well suited to the storage of genetic information, while base-pairing between DNA and incoming nucleotides provides the mechanism through which DNA polymerase replicates DNA and RNA polymerase transcribes DNA into RNA. Many DNA-binding proteins can recognize specific base-pairing patterns that identify particular regulatory regions of genes.

Intramolecular base pairs can occur within single-stranded nucleic acids. This is particularly important in RNA molecules (e.g., transfer RNA), where Watson–Crick base pairs (guanine–cytosine and adenine-uracil) permit the formation of short double-stranded helices, and a wide variety of non–Watson–Crick interactions (e.g., G–U or A–A) allow RNAs to fold into a vast range of specific three-dimensional structures. In addition, base-pairing between transfer RNA (tRNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA) forms the basis for the molecular recognition events that result in the nucleotide sequence of mRNA becoming translated into the amino acid sequence of proteins via the genetic code.

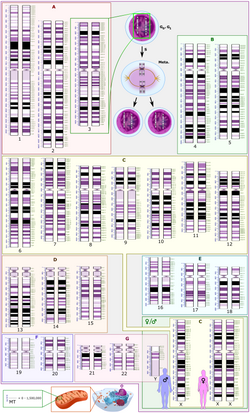

The size of an individual gene or an organism's entire genome is often measured in base pairs because DNA is usually double-stranded. Hence, the number of total base pairs is equal to the number of nucleotides in one of the strands (with the exception of non-coding single-stranded regions of telomeres). The haploid human genome (23 chromosomes) is estimated to be about 3.2 billion base pairs long and to contain 20,000–25,000 distinct protein-coding genes.[3][4][5][6] A kilobase (kb) is a unit of measurement in molecular biology equal to 1000 base pairs of DNA or RNA.[7] The total number of DNA base pairs on Earth is estimated at 5.0×1037 with a weight of 50 billion tonnes.[8] In comparison, the total mass of the biosphere has been estimated to be as much as 4 TtC (trillion tons of carbon).[9]

Notation

[edit]This article employs the "•" character in describing any noncovalant interaction, which includes all types of base pairs, in line with IUPAC's 1970 recommendation.[10]: N3.4.2

According to the IUPAC, "-" is not acceptable because it implies covalent linkage and neither are ":" and "/" because they can be mistaken as ratios. Not using any symbol is also unacceptable because it can be confused with a (covalent) polymer sequence.[10]: N3.4.2

IUPAC makes no specific recommendation for differentiating types of noncovalant bonds. When it is necessary to differentiate, this article uses "*" for the Hogsteen pair.

Hydrogen bonding and stability

[edit]

|

|

Hydrogen bonding is the chemical interaction that underlies the base-pairing rules described above. Appropriate geometrical correspondence of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors allows only the "right" pairs to form stably. DNA with high GC-content is more stable than DNA with low GC-content. Crucially, however, stacking interactions are primarily responsible for stabilising the double-helical structure; Watson-Crick base pairing's contribution to global structural stability is minimal, but its role in the specificity underlying complementarity is, by contrast, of maximal importance as this underlies the template-dependent processes of the central dogma (e.g. DNA replication).[11]

The bigger nucleobases, adenine and guanine, are members of a class of double-ringed chemical structures called purines; the smaller nucleobases, cytosine and thymine (and uracil), are members of a class of single-ringed chemical structures called pyrimidines. Purines are complementary only with pyrimidines: pyrimidine–pyrimidine pairings are energetically unfavorable because the molecules are too far apart for hydrogen bonding to be established; purine–purine pairings are energetically unfavorable because the molecules are too close, leading to overlap repulsion. Purine–pyrimidine base-pairing of AT or GC or UA (in RNA) results in proper duplex structure. The only other purine–pyrimidine pairings would be AC and GT and UG (in RNA); these pairings are mismatches because the patterns of hydrogen donors and acceptors do not correspond. The GU pairing, with two hydrogen bonds, does occur fairly often in RNA (see wobble base pair).

Paired DNA and RNA molecules are comparatively stable at room temperature, but the two nucleotide strands will separate above a melting point that is determined by the length of the molecules, the extent of mispairing (if any), and the GC content. Higher GC content results in higher melting temperatures; it is, therefore, unsurprising that the genomes of extremophile organisms such as Thermus thermophilus are particularly GC-rich. On the converse, regions of a genome that need to separate frequently — for example, the promoter regions for often-transcribed genes — are comparatively GC-poor (for example, see TATA box). GC content and melting temperature must also be taken into account when designing primers for PCR reactions.[citation needed]

Examples

[edit]The following DNA sequences illustrate pair double-stranded patterns. By convention, the top strand is written from the 5′-end to the 3′-end; thus, the bottom strand (complementary strand) is written 3′ to 5′.

- A base-paired DNA sequence:

ATCGATTGAGCTCTAGCGTAGCTAACTCGAGATCGC

- The corresponding RNA sequence, in which uracil is substituted for thymine in the RNA strand:

AUCGAUUGAGCUCUAGCGUAGCUAACUCGAGAUCGC

Non-canonical base pairing

[edit]In addition to the canonical Watson–Crick pairing (A•T/U G•C), some conditions can also favour base-pairing with alternative base orientation, and number and geometry of hydrogen bonds. These pairings are accompanied by alterations to the local backbone shape.[citation needed]

The most common of these is the wobble base pairing that occurs between tRNAs and mRNAs at the third base position of many codons during transcription[13] and during the charging of tRNAs by some tRNA synthetases.[14] They have also been observed in the secondary structures of some RNA sequences.[15]

Additionally, Hoogsteen base pairing (typically written as A*U/T and G*C) can happen when a different "face" of a purine base is used for pairing. This happens in some DNA sequences (e.g. CA and TA dinucleotides) in dynamic equilibrium with standard Watson–Crick pairing.[12] They have also been observed in some protein–DNA complexes.[16] There is also a kind of reverse Hoogsteen base pair in tRNA where both a purine and a pyrimidine uses a different "face".[17][18]

In addition to these alternative base pairings, a wide range of base-base hydrogen bonding is observed in RNA secondary and tertiary structure.[19] These bonds are often necessary for the precise, complex shape of an RNA, as well as its binding to interaction partners.[19]

Base pairs and mutation

[edit]Mismatch repair

[edit]Mismatched base pairs can be generated by errors of DNA replication and as intermediates during homologous recombination. The process of mismatch repair ordinarily must recognize and correctly repair a small number of base mispairs within a long sequence of normal DNA base pairs. To repair mismatches formed during DNA replication, several distinctive repair processes have evolved to distinguish between the template strand and the newly formed strand so that only the newly inserted incorrect nucleotide is removed (in order to avoid generating a mutation).[20] The proteins employed in mismatch repair during DNA replication, and the clinical significance of defects in this process are described in the article DNA mismatch repair. The process of mispair correction during recombination is described in the article gene conversion.

Base analogs and intercalators

[edit]Chemical analogs of nucleotides can take the place of proper nucleotides and establish non-canonical base-pairing, leading to errors (mostly point mutations) in DNA replication and DNA transcription. This is due to their isosteric chemistry. One common mutagenic base analog is 5-bromouracil, which resembles thymine but can base-pair to guanine in its enol form.[21]

Other chemicals, known as DNA intercalators, fit into the gap between adjacent bases on a single strand and induce frameshift mutations by "masquerading" as a base, causing the DNA replication machinery to skip or insert additional nucleotides at the intercalated site. Most intercalators are large polyaromatic compounds and are known or suspected carcinogens. Examples include ethidium bromide and acridine.[22]

As a unit of length

[edit]

The following abbreviations are commonly used to describe the length of a D/RNA molecule:

- bp = base pair—one bp corresponds to approximately 3.4 Å (340 pm)[23] of length along the strand, and to roughly 618 or 643 daltons for DNA and RNA respectively.

- kb (= kbp) = kilo–base-pair = 1,000 bp

- Mb (= Mbp) = mega–base-pair = 1,000,000 bp

- Gb (= Gbp) = giga–base-pair = 1,000,000,000 bp

For single-stranded DNA/RNA, units of nucleotides are used—abbreviated nt (or knt, Mnt, Gnt)—as they are not paired. To distinguish between units of computer storage and bases, kbp, Mbp, Gbp, etc. may be used for base pairs.

The centimorgan is also often used to imply distance along a chromosome, but the number of base pairs it corresponds to varies widely depending on the patterns of chromosomal crossover. In the human genome, the centimorgan is about 1 million base pairs.[24][25]

Unnatural base pair (UBP)

[edit]An unnatural base pair (UBP) is a designed subunit (or nucleobase) of DNA which is created in a laboratory and does not occur in nature. DNA sequences have been described which use newly created nucleobases to form a third base pair, in addition to the two base pairs found in nature, A•T (adenine – thymine) and G•C (guanine – cytosine). A few research groups have been searching for a third base pair for DNA, including teams led by Steven A. Benner, Philippe Marliere, Floyd E. Romesberg and Ichiro Hirao.[26] Some new base pairs based on alternative hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions and metal coordination have been reported.[27][28][29][30]

In 1989 Steven Benner (then working at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich) and his team led with modified forms of cytosine and guanine into DNA molecules in vitro.[31] The nucleotides, which encoded RNA and proteins, were successfully replicated in vitro. Since then, Benner's team has been trying to engineer cells that can make foreign bases from scratch, obviating the need for a feedstock.[32]

In 2002, Ichiro Hirao's group in Japan developed an unnatural base pair between 2-amino-8-(2-thienyl)purine (s) and pyridine-2-one (y) that functions in transcription and translation, for the site-specific incorporation of non-standard amino acids into proteins.[33] In 2006, they created 7-(2-thienyl)imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (Ds) and pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde (Pa) as a third base pair for replication and transcription.[34] Afterward, Ds and 4-[3-(6-aminohexanamido)-1-propynyl]-2-nitropyrrole (Px) was discovered as a high fidelity pair in PCR amplification.[35][28] In 2013, they applied the Ds-Px pair to DNA aptamer generation by in vitro selection (SELEX) and demonstrated the genetic alphabet expansion significantly augment DNA aptamer affinities to target proteins.[36]

In 2012, a group of American scientists led by Floyd Romesberg, a chemical biologist at the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, California, published that his team designed an unnatural base pair (UBP).[29] The two new artificial nucleotides or Unnatural Base Pair (UBP) were named d5SICS and dNaM. More technically, these artificial nucleotides bearing hydrophobic nucleobases, feature two fused aromatic rings that form a (d5SICS–dNaM) complex or base pair in DNA.[32][37] His team designed a variety of in vitro or "test tube" templates containing the unnatural base pair and they confirmed that it was efficiently replicated with high fidelity in virtually all sequence contexts using the modern standard in vitro techniques, namely PCR amplification of DNA and PCR-based applications.[29] Their results show that for PCR and PCR-based applications, the d5SICS–dNaM unnatural base pair is functionally equivalent to a natural base pair, and when combined with the other two natural base pairs used by all organisms, A–T and G–C, they provide a fully functional and expanded six-letter "genetic alphabet".[37]

In 2014 the same team from the Scripps Research Institute reported that they synthesized a stretch of circular DNA known as a plasmid containing natural T-A and C-G base pairs along with the best-performing UBP Romesberg's laboratory had designed and inserted it into cells of the common bacterium E. coli that successfully replicated the unnatural base pairs through multiple generations.[26] The transfection did not hamper the growth of the E. coli cells and showed no sign of losing its unnatural base pairs to its natural DNA repair mechanisms. This is the first known example of a living organism passing along an expanded genetic code to subsequent generations.[37][38] Romesberg said he and his colleagues created 300 variants to refine the design of nucleotides that would be stable enough and would be replicated as easily as the natural ones when the cells divide. This was in part achieved by the addition of a supportive algal gene that expresses a nucleotide triphosphate transporter which efficiently imports the triphosphates of both d5SICSTP and dNaMTP into E. coli bacteria.[37] Then, the natural bacterial replication pathways use them to accurately replicate a plasmid containing d5SICS–dNaM. Other researchers were surprised that the bacteria replicated these human-made DNA subunits.[39]

The successful incorporation of a third base pair is a significant breakthrough toward the goal of greatly expanding the number of amino acids which can be encoded by DNA, from the existing 20 amino acids to a theoretically possible 172, thereby expanding the potential for living organisms to produce novel proteins.[26] The artificial strings of DNA do not encode for anything yet, but scientists speculate they could be designed to manufacture new proteins which could have industrial or pharmaceutical uses.[40] Experts said the synthetic DNA incorporating the unnatural base pair raises the possibility of life forms based on a different DNA code.[39][40]

Data sources for base pair strengths

[edit]The following sources have information on the free energy (thermodynamic measures of strength) of base pairs:

- Vendeix et al. 2009, Table 1. Obtained by molecular simulation of RNA including canonical and modified bases. Free energy for 300 K.[41]

However, simply knowing what the minimal-energy hydrogen-bonded state between two nucleobases is not enough. The stability of a nucleic acid molecule also comes from base stacking, the stengths of which can vary with modified bases with respect to the original version. The optimal hydrogen-bonded state for two bases can also turn out to require an unnatural amount of bending of the nucleic acid backbone. All of these contribute to the "effective" strength of a base pair in the context of nucleic acid secondary structure, which is why predicting such structures need "nearest neighbor" models that describe base pairs in terms of free energy (at 37 °C) and enthalpy (for rescaling to different temperatures) of:[42]

- helix fragments such as AA•UU and GGUC•CUGG (the sequence on the left of the colon is in usual 5'-to-3' direction, but the one on the right is written in reversed 3'-to-5' direction)

- terminal mismatches (non-pairs at the end of helices, e.g. CA•GA).

A list of "nearest neighbor" models can be found at Nucleic acid structure prediction § Thermodynamic models.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Spencer M (10 January 1959). "The stereochemistry of deoxyribonucleic acid. II. Hydrogen-bonded pairs of bases". Acta Crystallographica. 12 (1): 66–71. Bibcode:1959AcCry..12...66S. doi:10.1107/S0365110X59000160. ISSN 0365-110X.

- ^ Zhurkin VB, Tolstorukov MY, Xu F, Colasanti AV, Olson WK (2005). "Sequence-Dependent Variability of B-DNA". DNA Conformation and Transcription. pp. 18–34. doi:10.1007/0-387-29148-2_2. ISBN 978-0-387-25579-8.

- ^ Moran LA (2011-03-24). "The total size of the human genome is very likely to be ~3,200 Mb". Sandwalk.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ "The finished length of the human genome is 2.86 Gb". Strategicgenomics.com. 2006-06-12. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ "One copy of the human genome consists of approximately 3 billion base pairs of DNA". National Human Genome Research Institute. 2024-08-24.

- ^ International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (October 2004). "Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome". Nature. 431 (7011): 931–945. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..931H. doi:10.1038/nature03001. PMID 15496913.

- ^ Cockburn AF, Newkirk MJ, Firtel RA (December 1976). "Organization of the ribosomal RNA genes of Dictyostelium discoideum: mapping of the nontranscribed spacer regions". Cell. 9 (4 Pt 1): 605–613. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(76)90043-X. PMID 1034500. S2CID 31624366.

- ^ Nuwer R (18 July 2015). "Counting All the DNA on Earth". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved 2015-07-18.

- ^ "The Biosphere: Diversity of Life". Aspen Global Change Institute. Basalt, CO. Archived from the original on 2014-11-10. Retrieved 2015-07-19.

- ^ a b IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (1970). "Abbreviations and symbols for nucleic acids, polynucleotides, and their constituents". Biochemistry. 9 (20): 4022–4027. doi:10.1021/bi00822a023.

- ^ Yakovchuk P, Protozanova E, Frank-Kamenetskii MD (2006-01-30). "Base-stacking and base-pairing contributions into thermal stability of the DNA double helix". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (2): 564–574. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj454. PMC 1360284. PMID 16449200.

- ^ a b Nikolova EN, Kim E, Wise AA, O'Brien PJ, Andricioaei I, Al-Hashimi HM (February 2011). "Transient Hoogsteen base pairs in canonical duplex DNA". Nature. 470 (7335): 498–502. Bibcode:2011Natur.470..498N. doi:10.1038/nature09775. PMC 3074620. PMID 21270796.

- ^ Murphy FV, Ramakrishnan V (December 2004). "Structure of a purine-purine wobble base pair in the decoding center of the ribosome". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 11 (12): 1251–1252. doi:10.1038/nsmb866. PMID 15558050. S2CID 27022506.

- ^ Vargas-Rodriguez O, Musier-Forsyth K (June 2014). "Structural biology: wobble puts RNA on target". Nature. 510 (7506): 480–481. Bibcode:2014Natur.510..480V. doi:10.1038/nature13502. PMID 24919145. S2CID 205239383.

- ^ Garg A, Heinemann U (February 2018). "A novel form of RNA double helix based on G·U and C·A+ wobble base pairing". RNA. 24 (2): 209–218. doi:10.1261/rna.064048.117. PMC 5769748. PMID 29122970.

- ^ Aishima J, Gitti RK, Noah JE, Gan HH, Schlick T, Wolberger C (December 2002). "A Hoogsteen base pair embedded in undistorted B-DNA". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (23): 5244–5252. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf661. PMC 137974. PMID 12466549.

- ^ Zagryadskaya EI, Doyon FR, Steinberg SV (July 2003). "Importance of the reverse Hoogsteen base pair 54-58 for tRNA function". Nucleic Acids Res. 31 (14): 3946–53. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg448. PMC 165963. PMID 12853610.

- ^ "Hoogsteen and reverse Hoogsteen base pairs". X3DNA-DSSR: a resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids.

- ^ a b Leontis NB, Westhof E (June 2003). "Analysis of RNA motifs". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 13 (3): 300–308. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(03)00076-9. PMID 12831880.

- ^ Putnam CD (September 2021). "Strand discrimination in DNA mismatch repair". DNA Repair. 105 103161. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2021.103161. PMC 8785607. PMID 34171627.

- ^ Trautner TA, Swartz MN, Kornberg A (March 1962). "Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. X. Influence of bromouracil substitutions on replication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 48 (3): 449–455. Bibcode:1962PNAS...48..449T. doi:10.1073/pnas.48.3.449. PMC 220799. PMID 13922323.

- ^ Krebs JE, Goldstein ES, Kilpatrick ST, Lewin B (2018). "Genes are DNA and Encode RNAs and Polypeptides". Lewin's genes XII (12th ed.). Burlington, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-284-10449-3.

Each mutagenic event in the presence of an acridine results in the addition or removal of a single base pair.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Morgan D, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (December 2014). Molecular Biology of the Cell (6th ed.). New York/Abingdon: Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-8153-4432-2.

- ^ "NIH ORDR – Glossary – C". Rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ Scott MP, Matsudaira P, Lodish H, Darnell J, Zipursky L, Kaiser CA, Berk A, Krieger M (2004). Molecular Cell Biology (Fifth ed.). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-7167-4366-8.

...in humans 1 centimorgan on average represents a distance of about 7.5x105 base pairs.

- ^ a b c Fikes BJ (May 8, 2014). "Life engineered with expanded genetic code". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Yang Z, Chen F, Alvarado JB, Benner SA (September 2011). "Amplification, mutation, and sequencing of a six-letter synthetic genetic system". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 133 (38): 15105–15112. Bibcode:2011JAChS.13315105Y. doi:10.1021/ja204910n. PMC 3427765. PMID 21842904.

- ^ a b Yamashige R, Kimoto M, Takezawa Y, Sato A, Mitsui T, Yokoyama S, Hirao I (March 2012). "Highly specific unnatural base pair systems as a third base pair for PCR amplification". Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (6): 2793–2806. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1068. PMC 3315302. PMID 22121213.

- ^ a b c Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Quach HT, Lavergne T, Ordoukhanian P, Torkamani A, Romesberg FE (July 2012). "Efficient and sequence-independent replication of DNA containing a third base pair establishes a functional six-letter genetic alphabet". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (30): 12005–12010. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912005M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205176109. PMC 3409741. PMID 22773812.

- ^ Takezawa Y, Müller J, Shionoya M (2017-05-05). "Artificial DNA Base Pairing Mediated by Diverse Metal Ions". Chemistry Letters. 46 (5): 622–633. doi:10.1246/cl.160985. ISSN 0366-7022.

- ^ Switzer C, Moroney SE, Benner SA (1989). "Enzymatic incorporation of a new base pair into DNA and RNA". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111 (21): 8322–8323. Bibcode:1989JAChS.111.8322S. doi:10.1021/ja00203a067.

- ^ a b Callaway E (May 7, 2014). "Scientists Create First Living Organism With 'Artificial' DNA". Nature News. Huffington Post. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Hirao I, Ohtsuki T, Fujiwara T, Mitsui T, Yokogawa T, Okuni T, et al. (February 2002). "An unnatural base pair for incorporating amino acid analogs into proteins". Nature Biotechnology. 20 (2): 177–182. doi:10.1038/nbt0202-177. PMID 11821864. S2CID 22055476.

- ^ Hirao I, Kimoto M, Mitsui T, Fujiwara T, Kawai R, Sato A, et al. (September 2006). "An unnatural hydrophobic base pair system: site-specific incorporation of nucleotide analogs into DNA and RNA". Nature Methods. 3 (9): 729–735. doi:10.1038/nmeth915. PMID 16929319. S2CID 6494156.

- ^ Kimoto M, Kawai R, Mitsui T, Yokoyama S, Hirao I (February 2009). "An unnatural base pair system for efficient PCR amplification and functionalization of DNA molecules". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (2): e14. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn956. PMC 2632903. PMID 19073696.

- ^ Kimoto M, Yamashige R, Matsunaga K, Yokoyama S, Hirao I (May 2013). "Generation of high-affinity DNA aptamers using an expanded genetic alphabet". Nature Biotechnology. 31 (5): 453–457. doi:10.1038/nbt.2556. PMID 23563318. S2CID 23329867.

- ^ a b c d Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Lavergne T, Chen T, Dai N, Foster JM, et al. (May 2014). "A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 385–388. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..385M. doi:10.1038/nature13314. PMC 4058825. PMID 24805238.

- ^ Sample I (May 7, 2014). "First life forms to pass on artificial DNA engineered by US scientists". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Scientists create first living organism containing artificial DNA". The Wall Street Journal. Fox News. May 8, 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b Pollack A (May 7, 2014). "Scientists Add Letters to DNA's Alphabet, Raising Hope and Fear". New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Vendeix, FA; Munoz, AM; Agris, PF (December 2009). "Free energy calculation of modified base-pair formation in explicit solvent: A predictive model". RNA. 15 (12): 2278–87. doi:10.1261/rna.1734309. PMC 2779691. PMID 19861423.

- ^ "Nearest Neighbor Database". 4 May 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Watson JD, Baker TA, Bell SP, Gann A, Levine M, Losick R (2004). Molecular Biology of the Gene (5th ed.). Pearson Benjamin Cummings: CSHL Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) (See esp. ch. 6 and 9) - Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK, eds. (2012). Interplay between Metal Ions and Nucleic Acids. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 10. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2172-2. ISBN 978-9-4007-2171-5. S2CID 92951134.

- Clever GH, Shionoya M (2012). "Alternative DNA Base Pairing through Metal Coordination". Interplay between Metal Ions and Nucleic Acids. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 10. pp. 269–294. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2172-2_10. ISBN 978-94-007-2171-5. PMID 22210343.

- Megger DA, Megger N, Mueller J (2012). "Metal-Mediated Base Pairs in Nucleic Acids with Purine- and Pyrimidine-Derived Nucleosides". Interplay between Metal Ions and Nucleic Acids. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 10. pp. 295–317. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2172-2_11. ISBN 978-94-007-2171-5. PMID 22210344.