Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Structural isomer

View on WikipediaThis article is written like a textbook. (August 2020) |

In chemistry, a structural isomer (or constitutional isomer in the IUPAC nomenclature[1]) of a compound is a compound that contains the same number and type of atoms, but with a different connectivity (i.e. arrangement of bonds) between them.[2][3] The term metamer was formerly used for the same concept.[4]

For example, butanol H3C−(CH2)3−OH, methyl propyl ether H3C−(CH2)2−O−CH3, and diethyl ether (H3CCH2−)2O have the same molecular formula C4H10O but are three distinct structural isomers.

The concept applies also to polyatomic ions with the same total charge. A classical example is the cyanate ion O=C=N− and the fulminate ion C−≡N+−O−. It is also extended to ionic compounds, so that (for example) ammonium cyanate [NH4]+[O=C=N]− and urea (H2N−)2C=O are considered structural isomers,[4] and so are methylammonium formate [H3C−NH3]+[HCO2]− and ammonium acetate [NH4]+[H3C−CO2]−.

Structural isomerism is the most radical type of isomerism. It is opposed to stereoisomerism, in which the atoms and bonding scheme are the same, but only the relative spatial arrangement of the atoms is different.[5][6] Examples of the latter are the enantiomers, whose molecules are mirror images of each other, and the cis and trans versions of 2-butene.

Among the structural isomers, one can distinguish several classes including skeletal isomers, positional isomers (or regioisomers), functional isomers, tautomers,[7] and structural isotopomers.[8]

Skeletal isomerism

[edit]A skeletal isomer of a compound is a structural isomer that differs from it in the atoms and bonds that are considered to comprise the "skeleton" of the molecule. For organic compounds, such as alkanes, that usually means the carbon atoms and the bonds between them.

For example, there are three skeletal isomers of pentane: n-pentane (often called simply "pentane"), isopentane (2-methylbutane) and neopentane (dimethylpropane).[9]

|

| |

| n-Pentane | Isopentane | Neopentane |

If the skeleton is acyclic, as in the above example, one may use the term chain isomerism.

Position isomerism (regioisomerism)

[edit]Position isomers (also positional isomers or regioisomers) are structural isomers that can be viewed as differing only on the position of a functional group, substituent, or some other feature on the same "parent" structure.[10]

For example, replacing one of the 12 hydrogen atoms –H by a hydroxyl group –OH on the n-pentane parent molecule can give any of three different position isomers:

|

|

|

| Pentan-1-ol | Pentan-2-ol | Pentan-3-ol |

Another example of regioisomers are α-linolenic and γ-linolenic acids, both octadecatrienoic acids, each of which has three double bonds, but on different positions along the chain.

Functional isomerism

[edit]Functional isomers are structural isomers which have different functional groups, resulting in significantly different chemical and physical properties.[11]

An example is the pair propanal H3C–CH2–C(=O)-H and acetone H3C–C(=O)–CH3: the first has a –C(=O)H functional group, which makes it an aldehyde, whereas the second has a C–C(=O)–C group, that makes it a ketone.

Another example is the pair ethanol H3C–CH2–OH (an alcohol) and dimethyl ether H3C–O–CH2H (an ether). In contrast, 1-propanol and 2-propanol are structural isomers, but not functional isomers, since they have the same significant functional group (the hydroxyl –OH) and are both alcohols.

Besides the different chemistry, functional isomers typically have very different infrared spectra. The infrared spectrum is largely determined by the vibration modes of the molecule, and functional groups like hydroxyl and esters have very different vibration modes. Thus 1-propanol and 2-propanol have relatively similar infrared spectra because of the hydroxyl group, which are fairly different from that of methyl ethyl ether.[citation needed]

Structural isotopomers

[edit]In chemistry, one usually ignores distinctions between isotopes of the same element. However, in some situations (for instance in Raman, NMR, or microwave spectroscopy) one may treat different isotopes of the same element as different elements. In the second case, two molecules with the same number of atoms of each isotope but distinct bonding schemes are said to be structural isotopomers.

Thus, for example, ethene would have no structural isomers under the first interpretation; but replacing two of the hydrogen atoms (1H) by deuterium atoms (2H) may yield any of two structural isotopomers (1,1-dideuteroethene and 1,2-dideuteroethene), if both carbon atoms are the same isotope. If, in addition, the two carbons are different isotopes (say, 12C and 13C), there would be three distinct structural isotopomers, since 1-13C-1,1-dideuteroethene would be different from 1-13C-2,2-dideuteroethene. And, in both cases, the 1,2-dideutero structural isotopomer would occur as two stereoisotopomers, cis and trans.

Structural equivalence and symmetry

[edit]Structural equivalence

[edit]Two molecules (including polyatomic ions) A and B have the same structure if each atom of A can be paired with an atom of B of the same element, in a one-to-one way, so that for every bond in A there is a bond in B, of the same type, between corresponding atoms; and vice versa.[3] This requirement applies also to complex bonds that involve three or more atoms, such as the delocalized bonding in the benzene molecule and other aromatic compounds.

Depending on the context, one may require that each atom be paired with an atom of the same isotope, not just of the same element.

Two molecules then can be said to be structural isomers (or, if isotopes matter, structural isotopomers) if they have the same molecular formula but do not have the same structure.

Structural symmetry and equivalent atoms

[edit]Structural symmetry of a molecule can be defined mathematically as a permutation of the atoms that exchanges at least two atoms but does not change the molecule's structure. Two atoms then can be said to be structurally equivalent if there is a structural symmetry that takes one to the other.[12]

Thus, for example, all four hydrogen atoms of methane are structurally equivalent, because any permutation of them will preserve all the bonds of the molecule.

Likewise, all six hydrogens of ethane (C

2H

6) are structurally equivalent to each other, as are the two carbons; because any hydrogen can be switched with any other, either by a permutation that swaps just those two atoms, or by a permutation that swaps the two carbons and each hydrogen in one methyl group with a different hydrogen on the other methyl. Either operation preserves the structure of the molecule. That is the case also for the hydrogen atoms in cyclopentane, allene, 2-butyne, hexamethylenetetramine, prismane, cubane, dodecahedrane, etc.

On the other hand, the hydrogen atoms of propane are not all structurally equivalent. The six hydrogens attached to the first and third carbons are equivalent, as in ethane, and the two attached to the middle carbon are equivalent to each other; but there is no equivalence between these two equivalence classes.

Symmetry and positional isomerism

[edit]Structural equivalences between atoms of a parent molecule reduce the number of positional isomers that can be obtained by replacing those atoms for a different element or group. Thus, for example, the structural equivalence between the six hydrogens of ethane C

2H

6 means that there is just one structural isomer of ethanol C

2H

5OH, not 6. The eight hydrogens of propane C

3H

8 are partitioned into two structural equivalence classes (the six on the methyl groups, and the two on the central carbon); therefore there are only two positional isomers of propanol (1-propanol and 2-propanol). Likewise there are only two positional isomers of butanol, and three of pentanol or hexanol.

Symmetry breaking by substitutions

[edit]Once a substitution is made on a parent molecule, its structural symmetry is usually reduced, meaning that atoms that were formerly equivalent may no longer be so. Thus substitution of two or more equivalent atoms by the same element may generate more than one positional isomer.

The classical example is the derivatives of benzene. Its six hydrogens are all structurally equivalent, and so are the six carbons; because the structure is not changed if the atoms are permuted in ways that correspond to flipping the molecule over or rotating it by multiples of 60 degrees. Therefore, replacing any hydrogen by chlorine yields only one chlorobenzene. However, with that replacement, the atom permutations that moved that hydrogen are no longer valid. Only one permutation remains, that corresponds to flipping the molecule over while keeping the chlorine fixed. The five remaining hydrogens then fall into three different equivalence classes: the one opposite to the chlorine is a class by itself (called the para position), the two closest to the chlorine form another class (ortho), and the remaining two are the third class (meta). Thus a second substitution of hydrogen by chlorine can yield three positional isomers: 1,2- or ortho-, 1,3- or meta-, and 1,4- or para-dichlorobenzene.

|

|

|

| ortho-Dichlorobenzene | meta-Dichlorobenzene | para-Dichlorobenzene |

| 1,2-Dichlorobenzene | 1,3-Dichlorobenzene | 1,4-Dichlorobenzene |

For the same reason, there is only one phenol (hydroxybenzene), but three benzenediols; and one toluene (methylbenzene), but three toluols, and three xylenes.

On the other hand, the second replacement (by the same substituent) may preserve or even increase the symmetry of the molecule, and thus may preserve or reduce the number of equivalence classes for the next replacement. Thus, the four remaining hydrogens in meta-dichlorobenzene still fall into three classes, while those of ortho- fall into two, and those of para- are all equivalent again. Still, some of these 3 + 2 + 1 = 6 substitutions end up yielding the same structure, so there are only three structurally distinct trichlorobenzenes: 1,2,3-, 1,2,4-, and 1,3,5-.

|

|

|

| 1,2,3-Trichlorobenzene | 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene | 1,3,5-Trichlorobenzene |

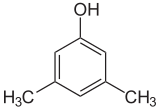

If the substituents at each step are different, there will usually be more structural isomers. Xylenol, which is benzene with one hydroxyl substituent and two methyl substituents, has a total of 6 isomers:

|

|

|

| 2,3-Xylenol | 2,4-Xylenol | 2,5-Xylenol |

|

|

|

| 2,6-Xylenol | 3,4-Xylenol | 3,5-Xylenol |

Isomer enumeration and counting

[edit]Enumerating or counting structural isomers in general is a difficult problem, since one must take into account several bond types (including delocalized ones), cyclic structures, and structures that cannot possibly be realized due to valence or geometric constraints, and non-separable tautomers.

For example, there are nine structural isomers with molecular formula C3H6O having different bond connectivities. Seven of them are air-stable at room temperature, and these are given in the table below.

| Name | Molecular structure | Melting point (°C) |

Boiling point (°C) |

Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allyl alcohol | –129 | 97 | ||

| Cyclopropanol | 101–102 | |||

| Propionaldehyde | –81 | 48 | Tautomeric with prop-1-en-1-ol, which has both cis and trans stereoisomeric forms | |

| Acetone |

|

–94.9 | 56.53 | Tautomeric with propen-2-ol |

| Oxetane | –97 | 48 | ||

| Propylene oxide | –112 | 34 | Has two enantiomeric forms | |

| Methyl vinyl ether | –122 | 6 |

Two structural isomers are the enol tautomers of the carbonyl isomers (propionaldehyde and acetone), but these are not stable.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Constitutional isomerism". IUPAC Gold Book. IUPAC. 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01285. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Frederick A. Bettelheim, William H. Brown, Mary K. Campbell, Shawn O. Farrell (2009): Introduction to Organic and Biochemistry. 752 pages. ISBN 9780495391166

- ^ a b Peter P. Mumba (2018): Useful Principles in Chemistry for Agriculture and Nursing Students, 2nd Edition. 281 pages. ISBN 9781618965288

- ^ a b William F. Bynum, E. Janet Browne, Roy Porter (2014): Dictionary of the History of Science. page 218. ISBN 9781400853410

- ^ Jim Clark (2000). "Structural isomerism" in Chemguide, n.l.

- ^ Poppe, Laszlo; Nagy, Jozsef; Hornyanszky, Gabor; Boros, Zoltan; Mihaly, Nogradi (2016). Stereochemistry and Stereoselective Synthesis: An Introduction. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-3-527-33901-3.

- ^ D. Brynn Hibbert, A.M. James (1987): Macmillan Dictionary of Chemistry. page 263. ISBN 9781349188178

- ^ "Isotopomer". IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology (3rd ed.). 2006. doi:10.1351/goldbook.I03352. online ver. 3.0.1 2019.

- ^ Zdenek Slanina (1986): Contemporary Theory of Chemical Isomerism. 254 pages. ISBN 9789027717078

- ^ H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry, 7th edition. 1232 pages. ISBN 9781305686182

- ^ Barry G. Hinwood (1997): A Textbook of Science for the Health Professions. 489 pages. ISBN 9780748733774

- ^ Jean-Loup Faulon, Andreas Bender (2010): Handbook of Chemoinformatics Algorithms. 454 pages. ISBN 9781420082999

- ^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 65th ed.

Structural isomer

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Structural isomers, also known as constitutional isomers, are molecules that possess the same molecular formula but differ in the connectivity of their atoms, resulting in distinct structural arrangements described by different line formulae.[3] This form of isomerism arises from variations in how atoms are bonded together, leading to compounds with potentially different physical and chemical properties despite sharing the same elemental composition.[4] The scope of structural isomerism is primarily confined to constitutional variants in both organic and inorganic chemistry, where the focus is on differences in atomic constitution rather than spatial orientation. It excludes stereoisomers, which maintain the same connectivity but vary in three-dimensional arrangement, and tautomers, which are rapidly interconverting constitutional forms typically not classified as stable structural isomers unless explicitly noted.[5] This distinction ensures that structural isomerism emphasizes fixed bonding differences, applicable across diverse chemical contexts from simple hydrocarbons to complex coordination compounds.[3] The recognition of structural isomerism emerged in the mid-19th century as part of the development of structural organic theory, pioneered by chemists like August Kekulé, who in 1857-1858 proposed that carbon's tetravalency enables varied atomic linkages to explain observed molecular diversity. A classic early example involves the C₄H₁₀ isomers n-butane and isobutane (2-methylpropane), first isolated and characterized in the 1860s from petroleum, illustrating how linear and branched carbon chains yield distinct compounds with the same formula. The structural formulas are:- n-Butane: CH₃-CH₂-CH₂-CH₃

- Isobutane: (CH₃)₂CH-CH₃

Comparison to Other Isomer Types

Structural isomers, also known as constitutional isomers, are distinguished from other types of isomers primarily by differences in the connectivity of atoms, while sharing the same molecular formula. According to IUPAC recommendations, isomers are species with identical atomic composition but differing line formulae (indicating connectivity) or stereochemical formulae (indicating spatial arrangement), leading to distinct properties.[6] Structural isomers specifically exhibit different line formulae, meaning the atoms are bonded in different sequences or arrangements, whereas stereoisomers maintain the same connectivity but differ in the three-dimensional orientation of atoms or groups.[6] This classification is based on IUPAC criteria requiring distinct constitutional diagrams for structural isomers, ensuring they cannot be superimposed by rotation or reflection without altering bond connections.[7] In contrast, stereoisomers include categories such as enantiomers (non-superimposable mirror images due to chirality) and diastereomers (stereoisomers that are not mirror images, often arising from geometric isomerism). For example, cis-trans isomers in alkenes like 2-butene represent stereoisomers because the carbon-carbon double bond restricts rotation, resulting in different spatial arrangements around the double bond without changing atom connectivity; these are not structural isomers. Atropisomers, such as certain biaryl compounds with bulky substituents, are another form of stereoisomers classified as stable conformers due to hindered rotation about a single bond, allowing isolation as separate entities, but they still share the same connectivity and thus differ from structural isomers.[8] Tautomers are a subset of structural isomers characterized by rapid interconversion, typically via proton transfer, as seen in keto-enol tautomerism where a compound like acetone equilibrates with its enol form; this mobility distinguishes them from typical structural isomers that do not interconvert easily under standard conditions.[9] Unlike stereoisomers, which require energy barriers like double bonds or chiral centers for stability, tautomers involve constitutional changes but are dynamically linked.[10] The following table summarizes key differences:| Aspect | Structural Isomers | Stereoisomers | Tautomers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Connectivity | Different (e.g., branched vs. straight chain) | Same | Different, but interconvertible |

| Spatial Arrangement | May vary, but not the defining feature | Different (e.g., cis vs. trans, R vs. S) | Varies with interconversion |

| Interconversion | Requires bond breaking/reformation | Requires rotation or reconfiguration without bond breaking | Rapid, often via proton shift |

| Example | n-Pentane vs. isopentane | (E)-2-butene vs. (Z)-2-butene | Acetone (keto) vs. enol form |

| Stability | Generally stable and isolable | Stable if barrier high (e.g., geometric) | Equilibrium mixture, not always isolable |