Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cord factor

View on Wikipedia | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C130H250O15 | |

| Molar mass | 2053.415 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

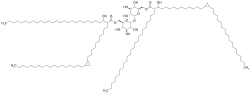

Cord factor, or trehalose dimycolate (TDM), is a glycolipid molecule found in the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and similar species. It is the primary lipid found on the exterior of M. tuberculosis cells.[1] Cord factor influences the arrangement of M. tuberculosis cells into long and slender formations, giving its name.[2] Cord factor is virulent towards mammalian cells and critical for survival of M. tuberculosis in hosts, but not outside of hosts.[3][4] Cord factor has been observed to influence immune responses, induce the formation of granulomas, and inhibit tumor growth.[5] The antimycobacterial drug SQ109 is thought to inhibit TDM production levels and in this way disrupts its cell wall assembly.[6]

Structure

[edit]A cord factor molecule is composed of a sugar molecule, trehalose (a disaccharide), composed of two glucose molecules linked together. Trehalose is esterified to two mycolic acid residues.[7][8] One of the two mycolic acid residues is attached to the sixth carbon of one glucose, while the other mycolic acid residue is attached to the sixth carbon of the other glucose.[7] Therefore, cord factor is also named trehalose-6,6'-dimycolate.[7] The carbon chain of the mycolic acid residues vary in length depending on the species of bacteria it is found in, but the general range is 20 to 80 carbon atoms.[3] Cord factor's amphiphilic nature leads to varying structures when many cord factor molecules are in close proximity.[3] On a hydrophobic surface, they spontaneously form a crystalline monolayer.[9] This crystalline monolayer is extremely durable and firm; it is stronger than any other amphiphile found in biology.[10] This monolayer also forms in oil-water, plastic-water, and air-water surfaces.[1] In an aqueous environment free of hydrophobic surfaces, cord factor forms a micelle.[11] Furthermore, cord factor interlocks with lipoarabinomannan (LAM), which is found on the surface of M. tuberculosis cells as well, to form an asymmetrical bilayer.[1][12] These properties cause bacteria that produce cord factor to grow into long, intertwining filaments, giving them a rope- or cord-like appearance when stained and viewed through a microscope (hence the name).[13]

Evidence of virulence

[edit]

A large quantity of cord factor is found in virulent M. tuberculosis, but not in avirulent M. tuberculosis.[1] Furthermore, M. tuberculosis loses its virulence if its ability to produce cord factor molecules is compromised.[1] Consequently, when all lipids are removed from the exterior of M. tuberculosis cells, the survival of the bacteria is reduced within a host.[14] When cord factor is added back to those cells, M. tuberculosis survives at a rate similar to that of its original state.[14] Cord factor increases the virulence of tuberculosis in mice, but it has minimal effect on other infections.[1]

Biological function

[edit]The function of cord factor is highly dependent on what environment it is located, and therefore its conformation.[15] This is evident as cord factor is harmful when injected with an oil solution, but not when it is with a saline solution, even in very large amounts.[15] Cord factor protects M. tuberculosis from the defenses of the host.[1] Specifically, cord factor on the surface of M. tuberculosis cells prevents fusion between phagosomal vesicles containing the M. tuberculosis cells and the lysosomes that would destroy them.[5][16] The individual components of cord factor, the trehalose sugars and mycolic acid residues, are not able to demonstrate this activity; the cord factor molecules must be fully intact.[5] Esterase activity that targets cord factor results in the lysis of M. tuberculosis cells.[17] However, the M. tuberculosis cells must still be alive to prevent this fusion; heat-killed cells with cord factor are unable to prevent being digested.[16] This suggests an additional molecule from M. tuberculosis is required.[16] Regardless, cord factor's ability to prevent fusion is related to an increased hydration force or through steric hindrance.[5] Cord factor remains on the surface of M. tuberculosis cells until it associates with a lipid droplet, where it forms a monolayer.[15] Then, as cord factor is in a monolayer configuration, it has a different function; it becomes fatal or harmful to the host organism.[18] Macrophages can die when in contact with monolayers of cord factor, but not when cord factor is in other configurations.[1] As the monolayer surface area of cord factor increases, so does its toxicity.[19] The length of the carbon chain on cord factor has also shown to affect toxicity; a longer chain shows higher toxicity.[20] Furthermore, fibrinogen has shown to adsorb to monolayers of cord factor and act as a cofactor for its biological effects.[21]

Cord factor isolated from species of Nocardia has been shown to cause cachexia in mice. Severe muscle wasting occurred within 48 hours of the toxin being administered.[22]

Host responses and cytokines

[edit]Numerous responses that vary in effect result from cord factor's presence in host cells. After exposure to cord factor for 2 hours, 125 genes in the mouse genome are upregulated.[23] After 24 hours, 503 genes are upregulated, and 162 genes are downregulated.[23] The exact chemical mechanisms by which cord factor acts is not completely known. However, it is likely that the mycolic acids of cord factor must undergo a cyclopropyl modification to lead to a response from the host's immune system for initial infection.[24] Furthermore, the ester linkages in cord factor are important for its toxic effects.[25] There is evidence that cord factor is recognized by the Mincle receptor, which is found on macrophages.[26][27] An activated Mincle receptor leads to a pathway that ultimately results in the production of several cytokines.[28][29] These cytokines can lead to further cytokine production that promote inflammatory responses.[30] Cord factor, through the Mincle receptor, also causes the recruitment of neutrophils, which lead to pro-inflammatory cytokines as well.[31] However, there is also evidence that toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in conjunction with the protein MyD-88 is responsible for cytokine production rather than the Mincle receptor.[23]

Cord factor presence increases the production of the cytokines interleukin-12 (IL-12), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), which are all pro-inflammatory cytokines important for granuloma formation.[16][28][32] IL-12 is particularly important in the defense against M. tuberculosis; without it, M. tuberculosis spreads unhampered.[33][34] IL-12 triggers production of more cytokines through T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, while also leading to mature Th1 cells, and thus leading to immunity.[35] Then, with IL-12 available, Th1 cells and NK cells produce interferon gamma (IFN-γ) molecules and subsequently release them.[36] The IFN-γ molecules in turn activate macrophages.[37]

When macrophages are activated by cord factor, they can arrange into granulomas around M. tuberculosis cells.[15][38] Activated macrophages and neutrophils also cause an increase in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is important for angiogenesis, a step in granuloma formation.[39] The granulomas can be formed either with or without T-cells, indicating that they can be foreign-body-type or hypersensitivity-type.[37] This means cord factor can stimulate a response by acting as a foreign molecule or by causing harmful reactions from the immune system if the host is already immunized.[37] Thus, cord factor can act as a nonspecific irritant or a T-cell dependent antigen.[37] Granulomas enclose M. tuberculosis cells to halt the bacteria from spreading, but they also allow the bacteria to remain in the host.[16] From there, the tissue can become damaged and the disease can transmit further with cord factor.[40] Alternatively, the activated macrophages can kill the M. tuberculosis cells through reactive nitrogen intermediates to remove the infection.[41]

Besides inducing granuloma formation, activated macrophages that result from IL-12 and IFN-γ are able to limit tumor growth.[42] Furthermore, cord factor's stimulation of TNF-α production, also known as cachectin, is also able to induce cachexia, or loss of weight, within hosts.[43][44] Cord factor also increases NADase activity in the host, and thus it lowers NAD; enzymes that require NAD decrease in activity accordingly.[3] Cord factor is thus able to obstruct oxidative phosphorylation and the electron transport chain in mitochondrial membranes.[3] In mice, cord factor has shown to cause atrophy in the thymus through apoptosis; similarly in rabbits, atrophy of the thymus and spleen occurred.[45][46] This atrophy occurs in conjunction with granuloma formation, and if granuloma formation is disturbed, so is the progression of atrophy.[46]

Scientific applications and uses

[edit]Infection by M. tuberculosis remains a serious problem in the world and knowledge of cord factor can be useful in controlling this disease.[24] For example, the glycoprotein known as lactoferrin is able to mitigate cytokine production and granuloma formation brought on by cord factor.[47] However, cord factor can serve as a useful model for all pathogenic glycolipids and therefore it can provide insight for more than just itself as a virulence factor.[11][48] Hydrophobic beads covered with cord factor are an effective tool for such research; they are able to reproduce an organism's response to cord factor from M. tuberculosis cells.[11][48] Cord factor beads are easily created and applied to organisms for study, and then easily recovered.[48]

It is possible to form cord factor liposomes through water emulsion; these liposomes are nontoxic and can be used to maintain a steady supply of activated macrophages.[49] Cord factor under proper control can potentially be useful in fighting cancer because IL-12 and IFN-γ are able to limit the growth of tumors.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Hunter, RL; Olsen, MR; Jagannath, C; Actor, JK (Autumn 2006). "Multiple roles of cord factor in the pathogenesis of primary, secondary, and cavitary tuberculosis, including a revised description of the pathology of secondary disease". Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 36 (4): 371–86. PMID 17127724.

- ^ Saita, N.; Fujiwara, N.; Yano, I.; Soejima, K.; Kobayashi, K. (1 October 2000). "Trehalose 6,6'-Dimycolate (Cord Factor) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Induces Corneal Angiogenesis in Rats". Infection and Immunity. 68 (10): 5991–5997. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.10.5991-5997.2000. PMC 101563. PMID 10992511.

- ^ a b c d e Rajni; Rao, N; Meena, LS (2011). "Biosynthesis and Virulent Behavior of Lipids Produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: LAM and Cord Factor: An Overview". Biotechnology Research International. 2011 274693. doi:10.4061/2011/274693. PMC 3039431. PMID 21350659.

- ^ Silva, CL; Ekizlerian, SM; Fazioli, RA (February 1985). "Role of cord factor in the modulation of infection caused by mycobacteria". The American Journal of Pathology. 118 (2): 238–47. PMC 1887869. PMID 3881973.

- ^ a b c d Spargo, BJ; Crowe, LM; Ioneda, T; Beaman, BL; Crowe, JH (Feb 1, 1991). "Cord factor (alpha,alpha-trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate) inhibits fusion between phospholipid vesicles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 88 (3): 737–40. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88..737S. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.3.737. PMC 50888. PMID 1992465.

- ^ TAHLAN, K., R. WILSON, D. B. KASTRINSKY, K. ARORA, V. NAIR, E. FISCHER, S. W. BARNES, J. R. WALKER, D. ALLAND, C. E. BARRY a H. I. BOSHOFF. SQ109 Targets MmpL3, a Membrane Transporter of Trehalose Monomycolate Involved in Mycolic Acid Donation to the Cell Wall Core of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2012-03-16, vol. 56, issue 4, s. 1797-1809. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.05708-11. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/doi/10.1128/AAC.05708-11

- ^ a b c NOLL, H; BLOCH, H; ASSELINEAU, J; LEDERER, E (May 1956). "The chemical structure of the cord factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 20 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(56)90289-x. PMID 13328853.

- ^ Jonsson, B. E.; Gilljam, M.; Lindblad, A.; Ridell, M.; Wold, A. E.; Welinder-Olsson, C. (21 March 2007). "Molecular Epidemiology of Mycobacterium abscessus, with Focus on Cystic Fibrosis". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 45 (5): 1497–1504. doi:10.1128/JCM.02592-06. PMC 1865885. PMID 17376883.

- ^ Retzinger, GS; Meredith, SC; Hunter, RL; Takayama, K; Kézdy, FJ (August 1982). "Identification of the physiologically active state of the mycobacterial glycolipid trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate and the role of fibrinogen in the biologic activities of trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate monolayers". Journal of Immunology. 129 (2): 735–44. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.129.2.735. PMID 6806381. S2CID 45693526.

- ^ Hunter, RL; Venkataprasad, N; Olsen, MR (September 2006). "The role of trehalose dimycolate (cord factor) on morphology of virulent M. tuberculosis in vitro". Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland). 86 (5): 349–56. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2005.08.017. PMID 16343989.

- ^ a b c Retzinger, GS; Meredith, SC; Takayama, K; Hunter, RL; Kézdy, FJ (Aug 10, 1981). "The role of surface in the biological activities of trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate. Surface properties and development of a model system". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 256 (15): 8208–16. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)43410-2. PMID 7263645.

- ^ Brennan, PJ (2003). "Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland). 83 (1–3): 91–7. doi:10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00089-6. PMID 12758196.

- ^ Bartelt, MA. (2000). Diagnostic Bacteriology: A Study Guide. Philadelphia, USA: F.A. Davis Company. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-8036-0301-1.

- ^ a b Indrigo, J; Hunter RL, Jr; Actor, JK (July 2002). "Influence of trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate (TDM) during mycobacterial infection of bone marrow macrophages". Microbiology. 148 (Pt 7): 1991–8. doi:10.1099/00221287-148-7-1991. PMID 12101287.

- ^ a b c d Hunter, Robert L.; Olsen, Margaret; Jagannath, Chinnaswamy; Actor, Jeffrey K. (April 2006). "Trehalose 6,6′-Dimycolate and Lipid in the Pathogenesis of Caseating Granulomas of Tuberculosis in Mice". The American Journal of Pathology. 168 (4): 1249–1261. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.050848. PMC 1606544. PMID 16565499.

- ^ a b c d e Indrigo, J; Hunter RL, Jr; Actor, JK (August 2003). "Cord factor trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate (TDM) mediates trafficking events during mycobacterial infection of murine macrophages". Microbiology. 149 (Pt 8): 2049–59. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26226-0. PMID 12904545.

- ^ Yang, Y.; Bhatti, A.; Ke, D.; Gonzalez-Juarrero, M.; Lenaerts, A.; Kremer, L.; Guerardel, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ojha, A. K. (15 November 2012). "Exposure to a Cutinase-like Serine Esterase Triggers Rapid Lysis of Multiple Mycobacterial Species". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (1): 382–392. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.419754. PMC 3537035. PMID 23155047.

- ^ Schabbing, RW; Garcia, A; Hunter, RL (February 1994). "Characterization of the trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate surface monolayer by scanning tunneling microscopy". Infection and Immunity. 62 (2): 754–6. doi:10.1128/IAI.62.2.754-756.1994. PMC 186174. PMID 8300239.

- ^ Geisel, RE; Sakamoto, K; Russell, DG; Rhoades, ER (Apr 15, 2005). "In vivo activity of released cell wall lipids of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin is due principally to trehalose mycolates". Journal of Immunology. 174 (8): 5007–15. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5007. PMID 15814731.

- ^ Fujita, Y; Okamoto, Y; Uenishi, Y; Sunagawa, M; Uchiyama, T; Yano, I (July 2007). "Molecular and supra-molecular structure related differences in toxicity and granulomatogenic activity of mycobacterial cord factor in mice". Microbial Pathogenesis. 43 (1): 10–21. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2007.02.006. PMID 17434713.

- ^ Sakamoto, K.; Geisel, R. E.; Kim, M.-J.; Wyatt, B. T.; Sellers, L. B.; Smiley, S. T.; Cooper, A. M.; Russell, D. G.; Rhoades, E. R. (22 December 2009). "Fibrinogen Regulates the Cytotoxicity of Mycobacterial Trehalose Dimycolate but Is Not Required for Cell Recruitment, Cytokine Response, or Control of Mycobacterial Infection". Infection and Immunity. 78 (3): 1004–1011. doi:10.1128/IAI.00451-09. PMC 2825938. PMID 20028811.

- ^ Silva, C. L.; Tincani, I.; Filho, S. L. B.; Faccioli, L. H. (1988-06-01). "Mouse Cachexia Induced by Trehalose Dimycolate from Nocardia asteroides". Microbiology. 134 (6): 1629–1633. doi:10.1099/00221287-134-6-1629. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 3065451.

- ^ a b c Sakamoto, K.; Kim, M. J.; Rhoades, E. R.; Allavena, R. E.; Ehrt, S.; Wainwright, H. C.; Russell, D. G.; Rohde, K. H. (21 December 2012). "Mycobacterial Trehalose Dimycolate Reprograms Macrophage Global Gene Expression and Activates Matrix Metalloproteinases". Infection and Immunity. 81 (3): 764–776. doi:10.1128/IAI.00906-12. PMC 3584883. PMID 23264051.

- ^ a b Rao, V; Fujiwara, N; Porcelli, SA; Glickman, MS (Feb 21, 2005). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis controls host innate immune activation through cyclopropane modification of a glycolipid effector molecule". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 201 (4): 535–43. doi:10.1084/jem.20041668. PMC 2213067. PMID 15710652.

- ^ Kato, M (March 1970). "Action of a toxic glycolipid of Corynebacterium diphtheriae on mitochondrial structure and function". Journal of Bacteriology. 101 (3): 709–16. doi:10.1128/JB.101.3.709-716.1970. PMC 250382. PMID 4314542.

- ^ Ishikawa, E; Ishikawa, T; Morita, YS; Toyonaga, K; Yamada, H; Takeuchi, O; Kinoshita, T; Akira, S; Yoshikai, Y; Yamasaki, S (Dec 21, 2009). "Direct recognition of the mycobacterial glycolipid, trehalose dimycolate, by C-type lectin Mincle". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 206 (13): 2879–88. doi:10.1084/jem.20091750. PMC 2806462. PMID 20008526.

- ^ Schoenen, H; Bodendorfer, B; Hitchens, K; Manzanero, S; Werninghaus, K; Nimmerjahn, F; Agger, EM; Stenger, S; Andersen, P; Ruland, J; Brown, GD; Wells, C; Lang, R (Mar 15, 2010). "Cutting edge: Mincle is essential for recognition and adjuvanticity of the mycobacterial cord factor and its synthetic analog trehalose-dibehenate". Journal of Immunology. 184 (6): 2756–60. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0904013. PMC 3442336. PMID 20164423.

- ^ a b Werninghaus, K.; Babiak, A.; Gross, O.; Holscher, C.; Dietrich, H.; Agger, E. M.; Mages, J.; Mocsai, A.; Schoenen, H.; Finger, K.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Brown, G. D.; Kirschning, C.; Heit, A.; Andersen, P.; Wagner, H.; Ruland, J.; Lang, R. (12 January 2009). "Adjuvanticity of a synthetic cord factor analogue for subunit Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccination requires FcR -Syk-Card9-dependent innate immune activation". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 206 (1): 89–97. doi:10.1084/jem.20081445. PMC 2626670. PMID 19139169.

- ^ Yamasaki, S; Ishikawa, E; Sakuma, M; Hara, H; Ogata, K; Saito, T (October 2008). "Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells". Nature Immunology. 9 (10): 1179–88. doi:10.1038/ni.1651. PMID 18776906. S2CID 205361789.

- ^ Welsh, K. J.; Abbott, A. N.; Hwang, S.-A.; Indrigo, J.; Armitige, L. Y.; Blackburn, M. R.; Hunter, R. L.; Actor, J. K. (1 June 2008). "A role for tumour necrosis factor- , complement C5 and interleukin-6 in the initiation and development of the mycobacterial cord factor trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate induced granulomatous response". Microbiology. 154 (6): 1813–1824. doi:10.1099/mic.0.2008/016923-0. PMC 2556040. PMID 18524936.

- ^ Lee, WB; Kang, JS; Yan, JJ; Lee, MS; Jeon, BY; Cho, SN; Kim, YJ (2012). "Neutrophils Promote Mycobacterial Trehalose Dimycolate-Induced Lung Inflammation via the Mincle Pathway". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (4) e1002614. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002614. PMC 3320589. PMID 22496642.

- ^ Roach, DR; Bean, AG; Demangel, C; France, MP; Briscoe, H; Britton, WJ (May 1, 2002). "TNF regulates chemokine induction essential for cell recruitment, granuloma formation, and clearance of mycobacterial infection". Journal of Immunology. 168 (9): 4620–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4620. PMID 11971010.

- ^ Cooper, A. M. (1 December 1993). "Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 178 (6): 2243–2247. doi:10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. PMC 2191280. PMID 8245795.

- ^ Cooper, AM; Magram, J; Ferrante, J; Orme, IM (Jul 7, 1997). "Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 186 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1084/jem.186.1.39. PMC 2198958. PMID 9206995.

- ^ Trinchieri, G (1995). "Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity". Annual Review of Immunology. 13 (1): 251–76. doi:10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. PMID 7612223.

- ^ Magram, Jeanne; Connaughton, Suzanne E; Warrier, Rajeev R; Carvajal, Daisy M; Wu, Chang-you; Ferrante, Jessica; Stewart, Colin; Sarmiento, Ulla; Faherty, Denise A; Gately, Maurice K (May 1996). "IL-12-Deficient Mice Are Defective in IFNγ Production and Type 1 Cytokine Responses". Immunity. 4 (5): 471–481. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80413-6. PMID 8630732.

- ^ a b c d Yamagami, H; Matsumoto, T; Fujiwara, N; Arakawa, T; Kaneda, K; Yano, I; Kobayashi, K (February 2001). "Trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate (cord factor) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces foreign-body- and hypersensitivity-type granulomas in mice". Infection and Immunity. 69 (2): 810–5. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.2.810-815.2001. PMC 97956. PMID 11159972.

- ^ Bekierkunst, A (October 1968). "Acute granulomatous response produced in mice by trehalose-6,6-dimycolate". Journal of Bacteriology. 96 (4): 958–61. doi:10.1128/JB.96.4.958-961.1968. PMC 252404. PMID 4971895.

- ^ Sakaguchi, I; Ikeda, N; Nakayama, M; Kato, Y; Yano, I; Kaneda, K (April 2000). "Trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate (Cord factor) enhances neovascularization through vascular endothelial growth factor production by neutrophils and macrophages". Infection and Immunity. 68 (4): 2043–52. doi:10.1128/iai.68.4.2043-2052.2000. PMC 97384. PMID 10722600.

- ^ Kobayashi, Kazuo; Kaneda, Kenji; Kasama, Tsuyoshi (15 May 2001). "Immunopathogenesis of delayed-type hypersensitivity". Microscopy Research and Technique. 53 (4): 241–245. doi:10.1002/jemt.1090. PMID 11340669. S2CID 1851137.

- ^ Chan, J; Xing, Y; Magliozzo, RS; Bloom, BR (Apr 1, 1992). "Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 175 (4): 1111–22. doi:10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. PMC 2119182. PMID 1552282.

- ^ Oswald, IP; Dozois, CM; Petit, JF; Lemaire, G (April 1997). "Interleukin-12 synthesis is a required step in trehalose dimycolate-induced activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages". Infection and Immunity. 65 (4): 1364–9. doi:10.1128/IAI.65.4.1364-1369.1997. PMC 175141. PMID 9119475.

- ^ Semenzato, G (March 1990). "Tumour necrosis factor: a cytokine with multiple biological activities". British Journal of Cancer. 61 (3): 354–361. doi:10.1038/bjc.1990.78. PMC 1971301. PMID 2183871.

- ^ Silva, CL; Faccioli, LH (December 1988). "Tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) mediates induction of cachexia by cord factor from mycobacteria". Infection and Immunity. 56 (12): 3067–71. doi:10.1128/IAI.56.12.3067-3071.1988. PMC 259702. PMID 3053451.

- ^ Hamasaki, N; Isowa, K; Kamada, K; Terano, Y; Matsumoto, T; Arakawa, T; Kobayashi, K; Yano, I (June 2000). "In vivo administration of mycobacterial cord factor (Trehalose 6, 6'-dimycolate) can induce lung and liver granulomas and thymic atrophy in rabbits". Infection and Immunity. 68 (6): 3704–9. doi:10.1128/iai.68.6.3704-3709.2000. PMC 97662. PMID 10816531.

- ^ a b Ozeki, Y; Kaneda, K; Fujiwara, N; Morimoto, M; Oka, S; Yano, I (May 1997). "In vivo induction of apoptosis in the thymus by administration of mycobacterial cord factor (trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate)". Infection and Immunity. 65 (5): 1793–9. doi:10.1128/IAI.65.5.1793-1799.1997. PMC 175219. PMID 9125563.

- ^ Welsh, Kerry J.; Hwang, Shen-An; Hunter, Robert L.; Kruzel, Marian L.; Actor, Jeffrey K. (October 2010). "Lactoferrin modulation of mycobacterial cord factor trehalose 6-6'-dimycolate induced granulomatous response". Translational Research. 156 (4): 207–215. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2010.06.001. PMC 2948024. PMID 20875896.

- ^ a b c Retzinger, GS (April 1987). "Dissemination of beads coated with trehalose 6,6'-dimycolate: a possible role for coagulation in the dissemination process". Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 46 (2): 190–8. doi:10.1016/0014-4800(87)90065-7. PMID 3556532.

- ^ Lepoivre, M; Tenu, JP; Lemaire, G; Petit, JF (August 1982). "Antitumor activity and hydrogen peroxide release by macrophages elicited by trehalose diesters". Journal of Immunology. 129 (2): 860–6. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.129.2.860. PMID 6806386.

- ^ Oswald, IP; Afroun, S; Bray, D; Petit, JF; Lemaire, G (September 1992). "Low response of BALB/c macrophages to priming and activating signals". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 52 (3): 315–22. doi:10.1002/jlb.52.3.315. PMID 1381743. S2CID 2190434.