Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cowrie

View on Wikipedia

| Cowrie Cowry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cowries are generally seen on rocky areas of the sea bed. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Caenogastropoda |

| Order: | Littorinimorpha |

| Superfamily: | Cypraeoidea |

| Family: | Cypraeidae |

Cowrie or cowry (pl. cowries) is the common name for a group of small to large sea snails in the family Cypraeidae.

Cowrie shells have held cultural, economic, and ornamental significance in various cultures. The cowrie was the shell most widely used worldwide as shell money. It is most abundant in the Indian Ocean, and was collected in the Maldive Islands, in Sri Lanka, along the Indian Malabar coast, in Borneo and on other East Indian islands, in Maluku in the Pacific, in Papua New Guinea and in various parts of the African coast from Ras Hafun, in Somalia, to Mozambique. Cowrie shell money was important in the trade networks of Africa, South Asia, and East Asia.

In the United States and Mexico, cowrie species inhabit the waters off Central California to Baja California (the chestnut cowrie is the only cowrie species native to the eastern Pacific Ocean off the coast of the United States; further south, off the coast of Mexico, Central America and Peru, Little Deer Cowrie habitat can be found; and further into the Pacific from Central America, the Pacific habitat range of Money Cowrie can be reached [1]) as well as the waters south of the Southeastern United States.[2]

Some species in the family Ovulidae are also often referred to as cowries. In the British Isles the local Trivia species (family Triviidae, species Trivia monacha and Trivia arctica) are sometimes called cowries. The Ovulidae and the Triviidae are other families within Cypraeoidea, the superfamily of cowries and their close relatives.

Etymology

[edit]The word cowrie comes from Hindi कौडि (kaudi), which is itself derived from Sanskrit कपर्द (kaparda).[3][4]

The term porcelain derives from the old Italian term for the cowrie shell (porcellana) due to their similar appearance.[5]

Shell description

[edit]

The shells of cowries are usually smooth and shiny and more or less egg-shaped. The round side of the shell is called the Dorsal Face, whereas the flat under side is called the Ventral Face, which shows a long, narrow, slit-like opening (aperture), which is often toothed at the edges. The narrower end of the egg-shaped cowrie shell is the anterior end, and the broader end of the shell is called the posterior. The spire of the shell is not visible in the adult shell of most species, but is visible in juveniles, which have a different shape from the adults.

Nearly all cowries have a porcelain-like shine, with some exceptions such as Hawaii's granulated cowrie, Nucleolaria granulata. Many have colorful patterns. Lengths range from 5 mm (0.2 in) for some species up to 19 cm (7.5 in) for the Atlantic deer cowrie, Macrocypraea cervus.

Human use

[edit]Monetary use

[edit]Cowrie shells, especially Monetaria moneta, were used for centuries as currency by native Africans. (The money cowrie was almost impossible to counterfeit until the late 19th century.[6]) Starting more than three thousand years ago, cowrie shells, or copies of the shells, were used as Chinese currency.[7] They were also used as means of exchange in India.

The Classical Chinese character for money (貝) originated as a stylized drawing of a Maldivian cowrie shell.[8][9] Words and characters concerning money, property or wealth usually have this as a radical. Before the Spring and Autumn period the cowrie was used as a type of trade token awarding access to a feudal lord's resources to a worthy vassal.[citation needed]

After the 1500s, the shell's use as currency became even more common. Western nations, chiefly through the slave trade, introduced huge numbers of Maldivian cowries in Africa.[10] In parts of British West Africa, cowries remained accepted for tax payments until the early 20th centuries, and their use as currency in unregulated environments persisted until the 1960s.[11]: 172, 208 The national currency of Ghana introduced in 1965, the cedi, was named after cowrie shells.

Ritual use

[edit]Cowrie shells are used in divination amongst the Yoruba people of West Africa (cf. Ifá and the annual customs of Dahomey of Benin).

The indigenous Ojibwe people of North America use cowrie shells which are called miigis shells or whiteshells in Midewiwin ceremonies, and the Whiteshell Provincial Park in Manitoba, Canada is named after this type of shell.[12] There is some debate[by whom?] about how the Ojibwe traded for or found these shells, so far inland and so far north, very distant from the natural habitat. Oral stories and birch bark scrolls seem to indicate that the shells were found in the ground, or washed up on the shores of lakes or rivers. Finding the cowrie shells so far inland could indicate the previous use of them by an earlier group in the area, who may have obtained them through an extensive trade network in the past.[citation needed]

In Eastern India, particularly in West Bengal, it is given as a token price for the ferry ride of the departed soul to cross the river "Vaitarani". Cowries are used during cremation. Cowries are also used in the worship of Goddess Laxmi.

In Brazil, as a result of the Atlantic slave trade from Africa, cowrie shells (called búzios) are also used to consult the Orixás divinities and hear their replies.

Cowrie shells were among the devices used for divination by the Kaniyar Panicker astrologers of Kerala, India.[13]

In certain parts of Africa, cowries were prized charms, and they were said to be associated with fecundity, sexual pleasure and good luck.[14] It is also used in the treatment of certain diseases such as rashes and ringworm when it is burnt into ashes.[15]

In Pre-dynastic Egypt and Neolithic Southern Levant, cowrie shells were placed in the graves of young girls.[16] The modified Levantine cowries were discovered ritually arranged around the skull in female burials. During the Bronze Age, cowries became more common as funerary goods, also associated with burials of women and children.[17] The cowroid was an Egyptian seal-amulet imitating the cowrie shell. Their imitations in stone or faience appear in the early 2nd millennium B.C.

Jewelry

[edit]

Cowrie shells are also worn as jewelry or otherwise used as ornaments or charms. In Mende culture, cowrie shells are viewed as symbols of womanhood, fertility, birth and wealth.[18] Its underside is supposed, by one modern ethnographic author, to represent a vulva or an eye.[19]

On the Fiji Islands, a shell of the golden cowrie or bulikula, Cypraea aurantium, was drilled at the ends and worn on a string around the neck by chieftains as a badge of rank.[20] The women of Tuvalu use cowrie and other shells in traditional handicrafts.[21]

Games and gambling

[edit]Cowrie shells are sometimes used in a way similar to dice, e.g., in board games like Pachisi and Ashta Chamma. A number of shells (6 or 7 in Pachisi) are thrown, with those landing aperture upwards indicating the actual number rolled.[22]

In Nepal cowries are used for a gambling game, where 16 pieces of cowries are tossed by four different bettors (and sub-bettors under them). This game is usually played at homes and in public during the Hindu festival of Tihar[23] or Deepawali. In the same festival these shells are also worshiped as a symbol of Goddess Lakshmi and wealth.[citation needed]

Other

[edit]Large cowrie shells such as that of a Cypraea tigris have been used in Europe in the recent past as a darning egg over which sock heels were stretched. The cowrie's smooth surface allows the needle to be positioned under the cloth more easily. [citation needed]

In the 1940s and 1950s, small cowry shells were used as a teaching aid in infant schools e.g counting, adding, subtracting.

-

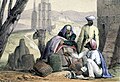

Print from 1845 shows cowrie shells being used as money by an Arab trader.

-

Antiquities of Native Americans, particularly of the Georgia tribes (1873)

-

Cowrie shells used as dice, showing a roll of 3

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Koerper, Henry C.; Whitney-Desautels, Nancy (1999). "A Cowry Shell Artifact from Bolsa Chica : An Example of Prehistoric Exchange" (PDF). Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly. 35 (2 & 3). Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. "Cowrie". Infoplease.com. Columbia University Press.

- ^ "Cowri". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. July 2023. cowrie (n.), Etymology. doi:10.1093/OED/4018863654.

- ^ "Home : Oxford English Dictionary". Oed.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Hogendorn, Jan; Johnson, Marion (September 2003). The Shell Money of the Slave Trade | Regional history after 1500. African Studies Series 49. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521541107.

- ^ "Money Cowries" Archived 5 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Ardis Doolin in Hawaiian Shell News, NSN #306, June 1985

- ^ Shen, Xu. "Shuowen Jiezi". cgi-bin/zipux2.cgi?b5=%A8%A9. Translated by L.Davrout. Yale press: Dover Publications. Archived from the original (zhongwen.com) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Bertsch, Wolfgang (Autumn 2000). "The Use of Maldivian Cowries as Money According to an 18th Century Portuguese Dictionary on World Currencies" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter. 165: 18 – via Oriental Numismatic Society Archive.

- ^ Weaver, Janice E. (September 1988). "Jan Hogendorn and Marion Johnson. The Shell Money of the Slave Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986". African Studies Review. 31 (2). Drake University: African Studies Association, Cambridge University Press (published 23 May 2014). doi:10.2307/524433. JSTOR 524433. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Helleiner, Eric (2003). The Making of National Money: Territorial Currencies in Historical Perspective. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- ^ Toulouse, Pamela Rose (2018). Truth and Reconciliation in Canadian Schools. Portage & Main Press. p. 65. ISBN 9781553797463.

- ^ Panikkar, T. K. Gopal (1995) [1900]. Malabar and its folk (2nd reprinted ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 257. ISBN 978-81-206-0170-3.

- ^ Tresidder, Jack (1997). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Symbols. London: Helicon. p. 53. ISBN 1-85986-059-1.

- ^ Ameade, Evans Paul Kwame; Dayah, Barnabas; Kouame, Lovis Nsoua Abina; Edmond, Saavielung Yaganomo; Abraham, Bodong; James, Balansuah Bayuo; Stephen, Gmawurim; Abagna, Linda Adobagna; Adom, Emmanuel (19 May 2023). "Current Uses of Cowries in Traditional Medicine After their Disuse as Currency-A Cross-Sectional Study in Ghana". Advances in Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 7 (4): 727–732.

- ^ Golani, Amir (2014). "Cowrie Shells and their Imitations as Ornamental Amulets in Egypt and the Near East". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranea: 71–94.

- ^ Kovács 2008: 17

- ^ Radiance from the Waters: Ideals of Feminine Beauty in Mende Art by Sylvia Ardyn Boone. Yale University Press, 1986.

- ^ Hildburgh, W. L. (1942). "Cowrie Shells as Amulets in Europe". Folklore. 53 (4): 178–195. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1942.9717654. JSTOR 1257370.

- ^ Cowries as a badge of rank in Fiji. (archived)

- ^ Tiraa-Passfield, Anna (September 1996). "The uses of shells in traditional Tuvaluan handicrafts" (PDF). SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin #7. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Brown, W. Norman (May 1964). "The Indian Games of Pachisi, Chaupar, and Chausar". Expedition Magazine 6, no. 3. Retrieved 28 September 2025.

- ^ "Tihar". Yeti Trial Adventure. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Felix Lorenz; Alex Hubert (1999). A Guide to Worldwide Cowries. Conchbooks. ISBN 978-3-925-91925-1.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cypraeidae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cypraeidae at Wikimedia Commons- Cowrie Genomic Database Project

- Genus Cypraea on Animal Diversity Web

- cowry.org – studying Hawaii's cowries

- Beautifulcowries – a gallery of images of cowries

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "miigis" at Wiktionary

Cowrie

View on GrokipediaBiological Aspects

Taxonomy and Classification

The cowries, comprising the family Cypraeidae (Rafinesque, 1815), are marine gastropod mollusks distinguished by their smooth, glossy shells formed through extensive mantle coverage during growth.[8] This family falls within the superfamily Cypraeoidea, order Littorinimorpha, subclass Caenogastropoda, class Gastropoda, phylum Mollusca, and kingdom Animalia.[8] The taxonomic structure reflects phylogenetic analyses incorporating morphological traits, such as shell microstructure and radular features, alongside molecular data from mitogenomes, which support monophyly of the family but reveal ongoing debates over subfamily and genus delimitations.[9] Cypraeidae encompasses nine subfamilies and approximately 55 genera, with around 245 valid species and 166 subspecies recognized as of recent inventories, though species counts vary due to splitting versus lumping practices in historical classifications.[9] [10] Key subfamilies include Cypraeinae (e.g., genus Cypraea Linnaeus, 1758) and Erroneinae, with genera like Monetaria and Lyncina often featuring in economic histories for their shell utility.[8] Alternative schemes, such as those uniting most taxa under a single genus Cypraea, have been proposed based on conservative morphology but are largely superseded by molecular phylogenies favoring greater subdivision to capture evolutionary divergence.[10] [9] Taxonomic revisions continue, informed by DNA sequencing that resolves polytomies in earlier trees and highlights Indo-Pacific radiations as the family's center of origin, with fossil records extending to the Eocene supporting deep-time stability at the family level.[9] Authorities like the World Register of Marine Species maintain the current framework, emphasizing synonymies from pre-molecular era descriptions to avoid overinflation of diversity.[8]Shell Morphology and Formation

Cowrie shells, produced by gastropods in the family Cypraeidae, exhibit a highly derived morphology distinct from most other snails. Adult shells are typically oval to elongated, with a thick, porcelaneous wall that provides a smooth, glossy exterior resembling polished porcelain. The dorsal surface is convex and rounded, while the ventral surface is flattened, accommodating the animal's foot and mantle. A long, narrow aperture runs along the ventral side, bordered by the outer lip (labrum) featuring 10–30 fine, interlocking teeth and the inner lip (columella) with 3–7 prominent, raised folds that aid in sealing the shell when retracted. The spire is greatly suppressed and often invisible from the exterior due to overgrowth by the mantle.[1][11][12] Juvenile cowries possess a more conventional spiral protoconch and early whorls resembling thin, elongated olive shells, with visible coiling and a simple aperture. As the animal matures, generally after 1–2 years depending on species and conditions, the outer lip expands and curves inward, forming the characteristic teeth, while the mantle deposits additional layers that obscure the spire and smooth the surface. This transformation results in a shell length ranging from 5 mm in small species like Cypraea moneta to over 150 mm in giants like Cypraea tigris, with widths about half the length.[13][14] Shell formation begins in the larval stage, where a delicate, aragonitic protoconch is secreted. Post-metamorphosis, the mantle—a soft epithelial tissue—continuously secretes calcium carbonate in the form of calcite crystals, primarily as the mineral's prismatic layer, augmented by organic proteins for strength. Unlike most gastropods, where the mantle skirts the shell's edge, the cowrie mantle fully envelops the exterior during growth and maintenance, depositing thin layers that polish the surface through abrasion and secretion of a waxy periostracum. This process incorporates trace elements such as magnesium and strontium into the lattice, enhancing durability and iridescence, with growth concentrated at the aperture margins rather than uniform expansion. The resulting shell consists of about 95% calcium carbonate, providing robust protection while minimizing weight.[15][11][16]Habitat, Distribution, and Ecology

Cowries of the family Cypraeidae inhabit tropical and subtropical marine waters globally, with the highest species diversity concentrated in the Indo-Pacific region, encompassing areas from East Africa through Indonesia, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea to the western Pacific.[1] Smaller numbers occur in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and northeast Pacific from central California to Baja California.[17] [18] These gastropods prefer hard-bottom substrates such as coral reefs, rocky outcrops, and crevices, where they seek shelter under stones or coral slabs, typically at depths from the intertidal zone to 40 meters.[18] [19] [3] They are benthic and often associate with live corals like Acropora, though some tolerate sandy areas near reefs.[3] Ecologically, cowries function as predators and grazers, employing a protrusible proboscis to consume sponges, algae, small invertebrates, soft corals, and detritus; certain species opportunistically feed on decaying coral tissue.[3] [20] Many are nocturnal, emerging at night to forage, while their colorful, extensible mantle camouflages them against reef substrates during the day.[3] Species such as the tiger cowrie (Cypraea tigris) prey on invasive sponges, potentially benefiting coral ecosystems by controlling overgrowth on native corals.[21]Nomenclature

Etymology

The English term "cowrie" entered usage in the mid-17th century, borrowed from Hindi kauṛī (कौड़ी), referring to the small, glossy shells employed as currency in Asian trade networks.[22] This Hindi form derives from Sanskrit kaparda (कपर्द), an ancient term denoting a compact tuft or cluster, extended to describe the shell's rounded, hair-like texture or its use in mimicking small aggregates in early monetary systems.[23] The word's transmission reflects Indo-European linguistic influences and the shells' widespread adoption in commerce from antiquity through the early modern period, with records of kauri variants appearing in Portuguese and Dutch trade documents by the 16th century as European powers engaged Indian Ocean routes.[23] Further tracing reveals potential Dravidian roots, with parallels to Tamil kavadi (கவடி), suggesting pre-Sanskritic origins in southern Indian coastal communities familiar with the shells' harvesting.[24] In Swahili, kauri evolved to connote porcelain-like sheen, underscoring the shell's aesthetic and material analogy to ceramics, though this is a secondary semantic shift rather than the primary etymon for the English form.[25] These derivations highlight the term's embedding in empirical trade histories, where the Cypraea moneta shell's durability and portability—evident in archaeological finds dating to 1200 BCE in the Maldives—necessitated standardized nomenclature across cultures.[23]Regional Names and Variations

In South Asia, cowrie shells are commonly known as kauri in Hindi, a term reflecting their longstanding use as a form of currency and reflecting Proto-Dravidian linguistic roots.[1] This name traces back to Tamil kavadi, denoting the small, glossy shells of species like Monetaria moneta, which were strung into necklaces or used in trade across the Indian subcontinent as early as the Vedic period around 1500 BCE.[25] In Bengali-speaking regions, indirect references appear in terms like mala for shell garlands, linking to the Maldives as a historical source of these shells.[5] In East Africa, particularly along Swahili Coast trade routes, the Kiswahili term kauri prevails, borrowed from Hindi via Indian Ocean commerce and evoking the shell's porcelain-like sheen; this usage dates to at least the 10th century CE in coastal societies where shells served as media of exchange.[25] Further west in Akan-speaking areas of modern Ghana, the word cedi—deriving directly from the local term for cowrie—underscores the shells' role in pre-colonial economies, with the national currency adopting this name upon independence in 1957 to symbolize enduring value.[26] Across Pacific Islander languages, names vary by archipelago, often tying to ornamental or ritual uses; for instance, in Polynesian dialects, terms akin to kauri or shell-specific descriptors appear in Hawaiian and Maori traditions, where larger species like Cypraea tigris (tiger cowrie) receive distinct identifiers for their spotted patterns, though small money cowries dominate monetary nomenclature.[1] Variations in naming also reflect ecological adaptations, with Indo-Pacific populations of Monetaria moneta showing regional size differences—smaller in high-density harvest zones like the Maldives (averaging 1-1.5 cm)—leading to localized qualifiers for "small" or "trade-grade" shells in indigenous trade pidgins.[27]Historical Monetary Use

Origins in Asia and Pacific

The earliest documented use of cowrie shells as currency occurred in ancient China during the Neolithic period (c. 3300–2000 BCE), particularly in northwestern regions such as Qinghai, Tibet, and Sichuan, where shells served as a medium of exchange alongside ornamental purposes.[28] Archaeological evidence from sites like Liuwan in Qinghai confirms their presence in burial contexts, suggesting economic value derived from scarcity and durability.[28] This practice intensified during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) through the early Spring and Autumn Period (c. 722–650 BCE), with cowries peaking as money in elite transactions and tomb offerings. Excavations at Anyang, the Shang capital in Henan, have yielded shells interred with bronze artifacts, while sites in Yunnan, such as Jinning and Jiangchuan, produced over 10,000 specimens from the Warring States to Western Han periods (c. 475 BCE–AD 9), indicating sustained circulation via trade.[28] Primarily Monetaria moneta and Monetaria annulus species, sourced from the Indian Ocean rather than local coasts, these shells were transported overland across the Eurasian Steppe, relying on networks that connected coastal harvesting grounds in the Maldives to inland Asia.[28] Their monetary function stemmed from intrinsic properties like uniformity, divisibility, and resistance to decay, often prompting imitations in bone, clay, and bronze to supplement supplies during shortages.[28][29] By the first millennium BCE, cowrie currency had diffused to South Asia, with evidence of use in Indian trade systems during the Vedic period (c. 1500–500 BCE), particularly in Bengal and Odisha, where shells facilitated exchange in agrarian economies.[30] In Southeast Asia, Neolithic sites reveal cowries as early trade items evolving into money by the mid-first millennium BCE, integrated into mainland networks from Thailand to Vietnam through maritime routes.[31] In the Pacific, adoption occurred later via Austronesian voyaging and Indian Ocean extensions, with shells functioning as currency in Melanesian islands like the Solomons from around the first millennium CE, though archaeological traces in Polynesia emphasize ornamental precedence over strict monetary roles until European contact amplified imports.[32][30]Adoption in Africa and Trade Routes

Cowrie shells, predominantly Monetaria moneta sourced from the Maldives, were introduced to African economies via Arab traders traversing trans-Saharan routes as early as the 8th century CE, initially gaining traction in North and West African markets for their portability and uniformity as exchange media.[33] Archaeological evidence confirms their presence along the Niger River bend by the 10th century, where local shell monies were supplemented or supplanted by these imported varieties, facilitating regional commerce in salt, gold, and slaves.[5] Adoption accelerated in West Africa during the medieval period, with cowries serving as standardized units—often strung in multiples of 40 or 20 for transactions—due to their scarcity relative to local goods and resistance to counterfeiting, as verified by their biological origin and limited supply chains.[34] Trade routes originated in the Indian Ocean, where Maldivian M. moneta shells were harvested en masse and exported northward to ports in India and the Arabian Peninsula, then relayed westward by camel caravans across the Sahara Desert to entrepôts like Timbuktu and Gao, integrating into Sahelian exchange networks by the 14th century.[7] From East African coastal Swahili ports such as Zanzibar, supplementary Cypraea annulus shells supplemented M. moneta, moving inland via monsoon winds and overland paths to central African societies, though West Africa dominated volumetric imports.[35] European intervention from the 16th century onward transformed these routes: Portuguese vessels first shipped cowries directly to Benin in 1515, bypassing Arab intermediaries, with subsequent Dutch and British fleets transporting billions of shells—peaking at over 50 million annually by the late 18th century—from European depots restocked via Indian Ocean voyages, enabling bulk exchanges for ivory, gold, and captives in coastal factories like those at Ouidah and Lagos.[34] [26] This influx via Atlantic routes, distinct from earlier Saharan paths, standardized cowrie valuation across West African polities—equivalent to fractions of a silver real or local iron bars—but precipitated devaluation as supply overwhelmed demand, with archaeological hoards revealing post-1650 dominance in commercial and ritual payments until colonial coinage phased them out by 1900.[7] In eastern and central Africa, adoption lagged, relying more on coastal Indian Ocean trade with fewer transcontinental volumes, underscoring the asymmetric economic pull of West African demand on global shell flows.[36] Empirical records from European ledgers and African oral histories affirm cowries' role in amplifying trade volumes, though their exogenous supply rendered African economies vulnerable to external manipulations, as evidenced by 19th-century inflation eroding purchasing power.[5]Economic Properties as Money

Cowrie shells, especially Cypraea moneta and Cypraea annulus, possessed key attributes that qualified them as a functional currency across diverse regions including Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. Their durability stemmed from the hard, glossy calcareous structure of the shells, which resisted physical degradation and maintained integrity over extended periods, unlike organic commodities such as grain or hides that deteriorated quickly.[37] [29] This longevity allowed cowries to serve reliably in transactions spanning generations without significant loss in form or usability.[38] The portability of cowrie shells facilitated their use in trade over vast distances; their small size and light weight enabled carriers to transport substantial quantities—equivalent to high values—without encumbrance, supporting commerce along Indian Ocean and trans-Saharan routes.[37] [39] For instance, in West African markets, bundles of thousands of shells could be moved efficiently by porters or in caravans, underpinning economic exchanges from local barter to international slave and commodity trades.[40] Divisibility was inherent in the individual nature of each shell, permitting precise subdivision of value for small-scale purchases, such as daily goods, while larger accumulations sufficed for major transactions like bridewealth or taxes.[29] [39] This feature contrasted with indivisible bulk goods, enabling cowries to function as a unit of account in standardized counts, often strung in strings of 40 or 2,400 for convenience in valuation.[40] Cowries demonstrated reasonable uniformity through their consistent oval shape and size, particularly for the "money cowrie" variant harvested from the Maldives, which minimized disputes over relative worth and supported fungibility in exchanges.[29] However, natural variations in shell quality occasionally posed challenges to perfect standardization, though cultural conventions often mitigated this by prioritizing specific types.[41] Their scarcity in non-indigenous regions endowed cowries with intrinsic value, as limited local availability—dependent on distant oceanic sourcing—prevented oversupply and preserved purchasing power until European imports disrupted this balance in the 19th century.[42] This relative rarity, combined with aesthetic appeal for jewelry, reinforced demand and acceptability across societies lacking alternative standardized media.[43] Widespread acceptability arose from cowries' established role in rituals and adornments, fostering trust and demand beyond mere utility; in West Africa, for example, they integrated into social payments and were recognized from Bengal trade networks to inland empires, evidencing a sophisticated, non-primitive monetary system.[40] [26] Such properties collectively enabled cowries to perform essential monetary functions—medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account—across Afro-Eurasian economies for millennia.[44]Inflation, Devaluation, and Decline

The influx of cowrie shells into West Africa, primarily through European trade networks during the 18th century, resulted in severe oversupply and subsequent inflation. Europeans, including British, Dutch, and French traders, imported over ten billion shells across the "Cowrie Zone" in that period alone, far exceeding local supply capacities and disrupting the currency's scarcity-based value.[30] This oversupply was exacerbated during the slave trade, where cowries served as a primary exchange medium; for instance, the price of an enslaved person in the African interior rose from approximately 172 shells in the 1710s to 160,000–176,000 by the 1770s, reflecting hyperinflation as more shells were required for equivalent transactions.[26][45] Devaluation accelerated in the late 19th century with continued imports despite waning demand, notably driven by firms like Adolf Jakob Hertz & Söhne in Hamburg, which realized 400% profit margins by shipping cheap East African cowries westward.[46] Hogendorn and Johnson document this "great cowrie inflation," attributing it to unchecked European shipments that flooded markets even as internal African economies shifted, causing the shells' exchange value to plummet relative to imported goods and metallic alternatives.[45][47] The decline culminated in colonial demonetization policies, as British authorities in West Africa sought to impose standardized currencies like silver coins and later paper notes to facilitate taxation and trade control. Efforts intensified from the 1880s onward, with outright bans in regions like Lagos by 1904, though cowries persisted in rural petty transactions until mid-20th-century inflation and legal prohibitions rendered them obsolete.[48][47] By the 1960s, their monetary role had vanished across former usage areas, supplanted by national fiat systems.[46]Cultural and Ritual Significance

In African Societies

In West African Yoruba traditions, cowrie shells serve as essential tools in divination rituals, particularly through the merindinlogun system, which utilizes sixteen shells cast onto a divination tray to generate one of 256 possible patterns interpreted as guidance from the orishas, the spiritual deities.[6] These shells, often the money cowrie (Cypraea moneta), represent the "mouths" of the orishas, with the diviner reciting associated verses and proverbs to convey spiritual insights during consultations addressing personal, communal, or health-related queries.[6] Beyond divination, cowrie shells feature prominently in Yoruba ritual artifacts, such as ibeji twin sculptures, where strings of shells adorn the figures to invoke fertility, protection, and prosperity for mothers grieving infant mortality, reflecting their enduring role in rites honoring twins—a common phenomenon in Yoruba culture with twin birth rates historically exceeding 4% in the region.[49] Carved or affixed cowries on such objects symbolize abundance and warding off misfortune, embedded in ceremonies that blend ancestral veneration with appeals for reproductive success.[49] In broader southwestern Nigerian communities, including Yoruba and related groups, cowrie shells retain ritual applications for spiritual safeguarding, such as amulets sewn into clothing or bags to repel malevolent forces during initiations or healing rites, persisting post their monetary obsolescence around the early 20th century.[50] Ethnographic surveys from 2015–2020 document their use in magical protections against evil eye or witchcraft, often combined with incantations, underscoring a causal link to perceived empirical efficacy in community-reported outcomes for ritual participants.[50] These practices highlight cowries' transition from economic to symbolic instruments, valued for their durable, portable form that aligns with pre-colonial trade influxes from the Maldives via Arab and European routes starting in the 16th century.[50]In Asian and Oceanic Cultures

In Hindu traditions prevalent across India and parts of Southeast Asia, cowrie shells, referred to as kaudi or kauri, are revered as sacred objects symbolizing prosperity, fertility, and the cyclical nature of existence, often linked to Goddess Lakshmi, the deity of wealth.[51][52] These shells are incorporated into rituals such as Laxmi Puja, where they are offered during prayers or placed in household altars and auspicious corners to attract financial blessings and avert misfortune; practitioners believe holding or displaying them channels divine favor from Lakshmi and sometimes Lord Shiva for success and abundance.[53][54] During the Diwali festival, observed annually in October or November, devotees specifically acquire cowrie shells to invoke Lakshmi's presence, positioning them in wallets, cash boxes, or pooja rooms as talismans against poverty.[55][56] Beyond Hinduism, cowrie shells feature in broader Asian spiritual practices as emblems of trade and material fortune, their smooth, glossy form evoking the ocean's bounty and enduring value in pre-modern economies that transitioned into ritual symbolism.[51] In Oceanic cultures, particularly among Polynesian and Melanesian communities in islands such as Fiji, Tonga, and the Solomons, cowrie shells serve ritual roles denoting leadership, strength, and spiritual safeguarding, frequently adorning ceremonial attire of chiefs and warriors to signify authority and invoke ancestral protection during communal rites.[57] Strung into necklaces or incorporated into ritual garments, they embody communal wealth and resilience, reflecting the shells' scarcity in inland or elevated terrains and their perceived infusion of oceanic vitality into social hierarchies.[58]Divination and Symbolism

In Yoruba-derived religious practices of West Africa, cowrie shells serve as a primary tool for divination, particularly in the system known as Ẹẹ́rìndínlógún, where 16 shells are ritually cast to produce one of 256 possible binary patterns, each interpreted as guidance from orishas or ancestral spirits.[59] This method, emphasizing the shells' "mouths" as voices of the divine, originated among the Yoruba people and relies on the diviner's trained intuition to convey messages on health, destiny, or conflict resolution.[60] In the African diaspora, such as in Lukumi (Santería) traditions of Cuba, the practice persists with similar mechanics, adapting Yoruba cosmology to examine an individual's spiritual state through shell configurations.[61] Beyond divination, cowrie shells carry rich symbolic meanings across cultures, often embodying protection and warding against malevolent forces; for instance, the Tiger Cowrie (Cypraea tigris) is placed in homes or altars in Indian traditions to deflect evil eye and black magic.[53] Their smooth, vulva-like shape evokes femininity, fertility, and safe childbirth, leading women in various African societies to wear them as amulets for conception and maternal safeguarding.[62] In Yoruba and related Orisha worship, cowries link to Yemayá, the ocean orisha of motherhood and the sea, symbolizing nurturing power, prosperity, and oceanic abundance.[63] These associations persist in rituals, where shells adorn regalia or serve as charms, reflecting enduring cultural attributions of resilience and divine favor rather than empirical causation.[64]Ornamental and Other Uses

Jewelry and Adornment

Cowrie shells, prized for their smooth, porcelain-like gloss and durable form, have been incorporated into jewelry and adornment practices worldwide since prehistoric eras, often perforated for stringing into beads. Archaeological findings indicate their use as ornaments dating back to Mesolithic times, with evidence of drilled shells in burial sites across Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, suggesting early symbolic roles in personal decoration.[65] In ancient Egypt, cowrie shells featured prominently in elite adornment during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2050–1710 BCE), as seen in the gold-inlaid girdle of Sithathoryunet, a princess whose jewelry included rows of cowrie-shaped beads symbolizing fertility and protection; such items were crafted by filling shell apertures with faience or gold to mimic the natural form.[66] Prehistoric Egyptian graves from around 3500 BCE also contain cowrie-adorned artifacts among lower-status individuals, highlighting their broad accessibility as fertility emblems before widespread metallurgical alternatives.[67] Across sub-Saharan African cultures, cowries were strung into necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and hair ornaments, valued for both aesthetic appeal and protective qualities against evil; for instance, Yoruba and other West African groups incorporated them into beaded regalia to denote status and spiritual safeguarding, with strands often numbering in the hundreds for elaborate pieces.[6] In Pacific Island societies, including Polynesian traditions, cowries adorned headdresses, belts, and pendants as markers of prosperity and divine favor, frequently combined with feathers or pearls for ceremonial wear.[68] South Asian and Southeast Asian archaeological sites yield cowrie beads from the Neolithic period onward, integrated into bangles and amulets, where their scarcity in inland regions underscored trade-driven prestige; by the 14th century, such uses persisted alongside monetary functions in India and China.[69] These adornments' enduring appeal stems from the shells' natural durability and iridescent sheen, which resisted wear better than many organic alternatives, though overharvesting later impacted availability.[70]Games, Gambling, and Toys

Cowrie shells, particularly the money cowrie (Monetaria moneta), have served as improvised dice in traditional games and gambling across Africa, Asia, and Oceania due to their binary landing orientation—aperture up or down—yielding outcomes akin to coin flips or numbered rolls. In South Asian board games like Pachisi and its variants, such as Chaupar, players typically throw four to six cowrie shells; the number of shells landing with the aperture facing up determines the move value, from 1 (one shell up) to 6 or 10 (all up, often a special "escape" roll). This practice, documented in historical accounts from the Mughal era, including Emperor Akbar's gameplay around 1570–1605, provided a fair randomizer with empirical probabilities favoring one side at approximately 30%, though variability exists by shell size and shape.[71][72] In African contexts, cowrie shells function similarly in strategy games and wagering. For instance, in the Ethiopian game Tamman, four shells are cast as dice, counting mouths-up (0 up equaling 8 points), influencing piece advancement on a board. West African mancala variants like Oware occasionally employ cowries as counters or supplementary randomizers in informal play, especially in regions where shells held monetary value. Gambling with cowries persists in some areas, such as Nepal's Durbar Square tosses read as "up" or "down" for bets, mirroring binary decision-making in African and Oceanic wagering traditions.[73][74] As toys, cowrie shells feature in children's playthings symbolizing abundance. In Cameroon, Namji people craft wooden fertility dolls adorned with cowrie shells, beads, and fibers; these dolls, given to girls around puberty but used earlier in play, teach social roles while the shells evoke prosperity. Coastal communities worldwide string shells into rattles or shakers for infants, fostering sensory development through sound and texture. Such uses highlight cowries' versatility beyond currency, embedding them in recreational and developmental activities.[75][76]Ethnomedical Applications

In West African traditional medicine, particularly among practitioners in Ghana, cowrie shells (Cypraea moneta) are incinerated, ground into ash or powder, and applied topically to treat dermatological conditions such as ringworm and skin rashes.[50] A 2023 cross-sectional study of traditional medical vendors in Ghana documented these applications as part of broader uses for physical ailments, comprising 23.5% of reported cowrie applications by clients, though empirical validation of efficacy remains limited to anecdotal and cultural reports rather than controlled trials.[77] Among the Yoruba people of Nigeria, cowrie shells serve as an ingredient in preparing herbal medicines, often combined with other botanicals for therapeutic formulations, reflecting their integration into pre-colonial pharmacopeia for unspecified ailments.[78] Shells may also be burned to ash for incorporation into remedies, aligning with symbolic associations of purity and protection that underpin their medicinal rationale, though historical accounts emphasize ritual over strictly physiological mechanisms.[79] In Hindu traditional practices in India, incinerated cowrie shells (Cypraea spp.) are added to medicinal mixtures to enhance purported healing properties, valued for their symbolic role in balancing bodily humors and promoting recovery, as described in classical texts and ethnobotanical compilations.[80] Such uses persist in Siddha and Ayurvedic-influenced systems, where shells contribute calcium-rich ashes for skeletal or antacid preparations, but lack robust pharmacological evidence beyond calcium content derived from shell composition.[81] Limited reports from traditional Chinese contexts suggest cowrie shells possess calming attributes for headache relief when processed into powders or amulets, though these derive primarily from folk traditions rather than canonical texts like the Bencao Gangmu, with modern interpretations emphasizing symbolic over empirical benefits.[82] Across these applications, cowrie shells' high chitin content offers potential biocompatibility for wound healing in contemporary derivations like chitosan, but traditional ethnomedical claims prioritize cultural causality over biochemical isolation.[81]Role in Global Trade and Controversies

Integration into European Trade Networks

The Portuguese initiated the large-scale importation of cowrie shells (Cypraea moneta) from the Maldives and Indian Ocean regions to West Africa around 1515, marking the entry of these shells into European-controlled transoceanic trade circuits.[26] This followed their establishment of maritime routes connecting the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, enabling the shells—already a medium of exchange in Asian and Pacific networks—to serve as a standardized commodity for bartering in African coastal entrepôts.[5] By leveraging cowries' portability, uniformity, and pre-existing cultural acceptance in West African societies, European traders bypassed local monetary preferences for gold or iron, facilitating deeper penetration into inland markets.[45] Dutch and British merchants expanded this network in the 17th and 18th centuries, sourcing shells primarily from Maldive atolls via intermediaries in India and Southeast Asia before transshipping them to ports along the Gold Coast and Bight of Benin.[83] British dominance emerged after 1750, with firms like the Royal African Company handling bulk cargoes until the 1807 abolition of the slave trade curtailed their operations.[83] Cowries became the dominant import to the Bight of Benin from 1650 to 1880, comprising up to 50% of traded goods by volume in some periods, as they were strung into standardized strings (typically 40-50 shells per unit) for equivalence with European textiles, firearms, and spirits.[34] In the 18th century alone, European powers imported over 10 billion cowrie shells to the "Cowrie Zone" spanning modern-day Nigeria to Senegal, equivalent to an annual influx of roughly 100-150 tons in peak decades.[30] This volume, documented in ship manifests and African royal accounts, underscores the shells' role as a proto-global currency bridging disparate economies, though their unilateral importation led to inflationary pressures as local supplies outpaced absorption rates.[45] Integration deepened through hybrid exchange systems, where cowries were assayed for quality at European forts like Elmina and Cape Coast Castle, ensuring their viability in multilateral trades involving ivory, palm oil, and enslaved labor.[7]Facilitation of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Europeans imported massive quantities of Monetaria moneta cowrie shells from the Maldives and Indian Ocean regions to West Africa specifically to serve as currency in exchanging for enslaved people during the transatlantic slave trade.[26][84] The Portuguese initiated large-scale shipments, with the first major delivery arriving in Benin City via Lisbon in 1515, marking the integration of cowries into Atlantic trade networks.[34] By the eighteenth century, European traders had shipped over ten billion shells across the "Cowrie Zone" of West Africa, enabling the purchase of slaves, cloth, and other goods.[30] This importation, often by the boatload from Indian ports, directly fueled African coastal states' acquisition of captives from interior regions, as cowries were a highly valued, portable medium of exchange that bridged local economies with global demand.[85][86] The scale of cowrie inflows amplified the slave trade's volume, with shells exchanged directly for human lives throughout the four centuries of transoceanic enslavement from West Africa.[84] In the 1770s, the price for one enslaved person in regions like the Niger Delta ranged from 160,000 to 176,000 cowries, reflecting both the shells' entrenched role as money and the inflationary pressures from oversupply, which nonetheless sustained trade momentum.[26] Coastal powers such as Dahomey and the Kingdom of Benin leveraged these imports to procure war captives and debtors from inland suppliers, converting cowries into labor for export to the Americas.[87][7] While cowries had pre-existed as currency in African systems dating back centuries, the European-driven influx—totaling billions from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries—created a monetary ecosystem tailored to the slave economy, where shells circulated alongside European goods but remained indispensable for final slave transactions.[49][88] This mechanism underscored a causal linkage: the reliability of cowries as a non-perishable, divisible store of value lowered transaction costs for slavers, allowing African intermediaries to amass wealth in shells for reinvestment in raids and tribute systems that expanded enslavement.[89] Historical records from European trading posts, such as those in Ouidah, document cowries as a staple payment alongside taxes and customs, binding local elites to the export of over 12 million enslaved Africans via West African ports.[90] The eventual devaluation from shell saturation contributed to the trade's later phases, but cowries' primacy persisted until British abolition efforts in the early nineteenth century disrupted imports.[91]Economic Critiques and Modern Analysis

The importation of vast quantities of cowrie shells into West Africa during the transatlantic slave trade era led to significant inflationary pressures, as the exogenous increase in money supply outpaced economic output. Between 1700 and 1790, Dutch and English traders alone shipped approximately 11,436 tonnes of cowries to the region, primarily to facilitate slave purchases, which equated to billions of individual shells flooding local markets.[45] This influx exemplified the quantity theory of money, where a rapid expansion of the medium of exchange (M in MV = PQ) drove up prices (P), eroding the shells' purchasing power; for instance, the price of a slave in cowries rose from around 80,000 shells in the 1760s to 160,000–176,000 by the 1770s in parts of the Bight of Benin, reflecting the need for more currency to transact the same value.[92] Economic historians Jan Hogendorn and Marion Johnson argue that while initial imports spurred trade expansion and monetization, the system's reliance on foreign supply created inherent instability, as local economies could not control issuance, leading to cycles of boom and devaluation rather than sustainable growth.[45] Critiques of cowrie-based economies highlight their vulnerability to manipulation and structural flaws that perpetuated dependency. European traders, aware of cowries' role in slave procurement, deliberately imported massive volumes—peaking at 396 tonnes annually in the 1840s—to depress local currency values, effectively lowering the real cost of slaves in European goods; this is evidenced by Portuguese records from 1515 onward, where shipments escalated from 500 quintals (about 56 tonnes) initially to thousands of tonnes by the 17th century.[89] Such practices not only fueled inflation but also discouraged investment in productive assets, as savings in cowries depreciated unpredictably; in Lagos, for example, the cowrie price index fell to 13 by 1895 from a baseline of 100 in 1850, rendering hoarded shells nearly worthless.[92] Colonial administrators further critiqued the currency for its logistical inefficiencies—bulky strings prone to breakage and loss in value over distance—prompting demonetization efforts, such as Nigeria's 1904 import ban and earlier British attempts on the Gold Coast, which viewed cowries as a barrier to integrating African economies into sterling-based systems.[93] These interventions, while aimed at stabilization, underscore a broader economic indictment: cowrie money, though initially effective for small-scale barter transitions, fostered extractive trade patterns that prioritized short-term European gains over long-term African monetary sovereignty. Modern economic analyses frame cowries as a cautionary case of commodity money's limitations under globalized supply chains. The introduction of cheaper East African Cypraea annulus shells after 1845—totaling 35,855 tonnes imported between 1851 and 1869—illustrates Gresham's Law in action, as inferior currency displaced higher-quality Maldive Monetaria moneta, accelerating hyperinflation and collapsing interregional trade networks by the 1890s.[92] Scholars like Hogendorn and Johnson apply causal models to show how transport costs and arbitrage opportunities initially sustained value but ultimately amplified devaluation when supply overwhelmed demand absorption, contrasting with more resilient metallic currencies that allowed endogenous control.[45] Contemporary studies, including those on West African monetary transitions, argue that cowrie dependency delayed adoption of stable, divisible media, contributing to persistent underdevelopment by eroding incentives for financial innovation and exposing economies to external shocks, such as the post-1807 British slave trade abolition, which halved imports and triggered deflationary contractions.[93] This perspective emphasizes causal realism: while cowries enabled transaction efficiency in precolonial barter systems, their integration into coercive global trade rendered them a vector for economic distortion rather than genuine prosperity.[45]Modern Uses and Conservation

Contemporary Crafts and Collectibles

Cowrie shells remain integral to modern handicrafts, particularly in jewelry fabrication where artisans employ techniques such as wire wrapping to secure shells onto earrings or pendants, often pairing them with beads or metal findings for customizable accessories.[94] Crafters also enhance shells through dyeing or nail polish application to achieve vibrant, bohemian-style pieces like anklets and chokers, blending traditional motifs with contemporary aesthetics.[95] Beyond personal adornment, these shells feature in decorative items including keychains, dreamcatchers, and mosaics, valued for their glossy texture and symbolic associations with prosperity and protection.[96] [97] As collectibles, cowrie shells attract hobbyists specializing in malacology, who curate specimens of species like Cypraea moneta or Cypraea tigris, documenting attributes such as size, coloration variants (e.g., melanistic forms), and provenance in detailed catalogs.[98] Collections are displayed using methods like Riker mounts for flat presentation, glass jars for naturalistic arrangements, or framed setups with driftwood backdrops to evoke marine origins.[99] Ethical guidelines among collectors emphasize harvesting only empty, beach-found shells to avoid depleting live populations, with some advocating photography over removal for sustainability.[100] This hobby persists through intergenerational transfers, as seen in family-inherited assemblages requiring identification and preservation efforts.[101]Overexploitation and Environmental Impact

The harvesting of cowrie shells for jewelry, souvenirs, and curios has caused localized population declines in regions with high collection pressure, such as tourist-heavy coastal areas in the Indo-Pacific. For instance, tiger cowries (Cypraea tigris) in Hawaii have undergone precipitous reductions attributable to overharvesting, diminishing their presence in populated nearshore habitats.[102] In Thailand, similar extraction for the collector and tourist markets has reduced local abundances, though broader regional monitoring remains limited.[103] These declines stem from the practice of collecting live specimens, which kills the mollusk and removes reproductive individuals from populations already vulnerable to slow growth rates and limited dispersal.[104] Cowries contribute to marine ecosystem stability as carnivorous predators and grazers, consuming sponges, polyps, barnacles, and algae on coral reefs and rocky substrates, thereby preventing overgrowth that could smother sessile organisms or reduce biodiversity.[1] [104] Their depletion disrupts these trophic interactions; for example, reduced cowrie predation has allowed invasive sponge proliferation in some Pacific locales, exacerbating habitat degradation alongside other stressors like climate change.[102] Additionally, the extraction of shells—especially in bulk—alters local biogeochemical cycles, including calcium carbonate deposition and nutrient recycling on beaches and seabeds, potentially amplifying erosion or acidification effects in affected microhabitats.[105] Globally, most cowrie species face no formal endangered listing under IUCN assessments, which classify many as data deficient or of least concern, reflecting stable populations outside heavily exploited zones.[106] Cowries are not included in CITES appendices, lacking international trade quotas, though some jurisdictions enforce local bans or size limits on collection to mitigate overexploitation.[107] Conservation responses emphasize habitat protection in marine reserves and sustainable harvesting guidelines, but challenges persist from unregulated informal trade and insufficient baseline data on population dynamics.[104]Archaeological and Research Insights

Archaeological evidence reveals cowrie shells (Monetaria spp.) were utilized as ornaments as early as the Early Epipaleolithic period in the Levant, dating to 22,000–16,000 cal. BC, with more systematic use emerging in the Middle and Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B periods at sites like Tell Halula in northern Syria (ca. 8100–6750 cal. BC), where shells from Red Sea and Mediterranean sources appeared in burials as belts, diadems, and status markers, often broken for maintenance or ritual purposes.[108] In ancient Egypt during the Ptolemaic Period (ca. 305–30 BC), cowrie shells, primarily sourced from the Red Sea, functioned as amulets symbolizing fertility due to their vulva-like shape, with imitations crafted in faience and other materials to enhance symbolic potency.[109] In West Africa, comprehensive analysis of 4,559 shells from 78 sites spans from the 5th–7th centuries AD at Kissi, Burkina Faso (where six Monetaria moneta shells were found in burials, likely as headpieces), to the 19th century, with peak concentrations in medieval inland contexts like Ma’den Ijafen (11th–12th centuries AD, yielding 3,433 shells, 94% unmodified).[34] Predominant species were Indo-Pacific M. moneta (earlier inland dominance) and M. annulus (later coastal prevalence), modified via dorsum removal for currency or adornment, indicating trans-Saharan and Atlantic trade influxes from the Maldives via Red Sea routes as early as 800–1400 CE, corroborated by 14th-century accounts of traveler Ibn Battuta describing their role as currency and jewelry in Mali.[110][7] Modern research leverages species identification, modification patterns, and contextual associations to reconstruct trade networks and social roles, revealing cowries' transition from prestige goods to standardized currency in West African societies, including Dahomey state economies (1650–1880), and their persistence in diaspora contexts like the 18th-century New York African Burial Ground (Burial 340, with seven waist-adorned shells symbolizing identity and ancestry).[7] These studies highlight shells' durability in archaeological records for tracing global connectivity, while unmodified hoards suggest economic stockpiling predating European involvement, challenging narratives of solely Atlantic-driven monetization.[34]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cowrie