Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Cryptodepression.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cryptodepression

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

A cryptodepression is a depression in the Earth's surface that is below mean sea level, and which is filled by a lake.[1][2]

Etymology

[edit]The term is derived from the Ancient Greek word κρυπτός 'hidden' and depression.

Description

[edit]A cryptodepression is often the result of a rift valley or a glaciation.[3] Such lakes are often long and narrow, and the surrounding landscape and the shore of the lake can be very steep.[4]

Examples

[edit]Lago O'Higgins/San Martín has a surface elevation of 250 meters and a maximal depth of 836 meters, yielding a cryptodepression of 586 meters.

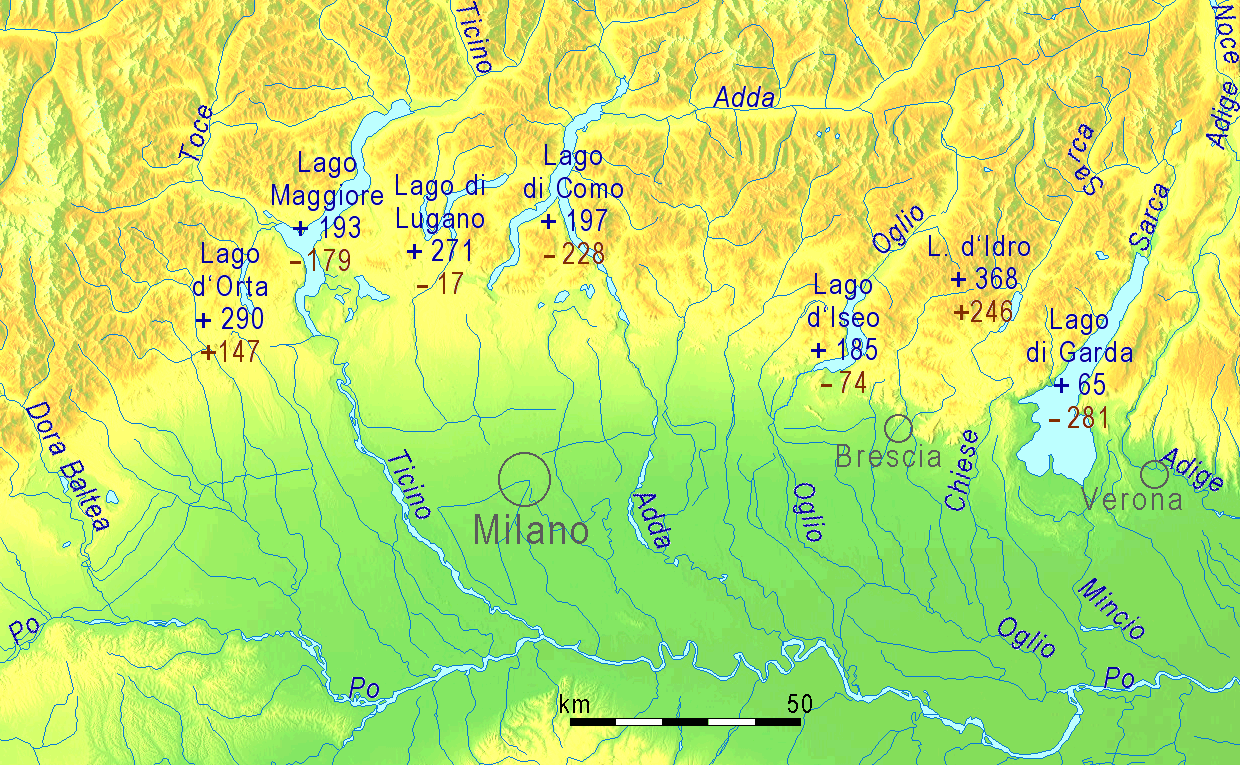

- Glacial lakes and moraine-dammed lakes: major prealpine lakes in Italy have cryptodepressions created by erosion. In other parts of the Alps, Swiss, Bavarian and Austrian lakes, cryptodepressions are not found because the lakes have significantly higher elevations. Glacial lakes creating cryptodepressions also occur in Norway, Chile, Argentina, Newfoundland, New Zealand, and Scotland. In North America, four of the five Great Lakes (all except Erie) and two of the Finger Lakes in New York, Cayuga Lake and Seneca Lake, are examples of cryptodepressions. Mälaren in Sweden was created by a different process; it had been an arm of the Baltic Sea as recently as the Viking Age before being cut off from the sea by post-glacial rebound.

- Rift valleys: the deepest known cryptodepression on Earth is in Lake Baikal (–1200 m).[4] Other notable examples include Lake Tanganyika and Lake Malawi in Africa's East African Rift.

References

[edit]Look up cryptodepression in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- ^ Fairbridge, R. W. (1968), "Cryptodepressions", in Fairbridge, R.W. (ed.), Geomorphology, Encyclopedia of Earth Science, Encyclopedia of Earth Science, vol. Geomorphology, Berlin: Springer, pp. 231–233, doi:10.1007/3-540-31060-6_78, ISBN 978-0-442-00939-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Neuendorf, K.K.E.; Mehl, Jr., J.P.; Jackson, J.A. (2005). Glossary of Geology (5th ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: American Geological Institute. p. 155.

- ^ "criptodepressione". Enciclopedia Treccani (in Italian). Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ a b Fairbridge, R. W. (1968), "Cryptodepressions", in Fairbridge, R.W. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Earth Science, vol. Geomorphology, Berlin: Springer, archived from the original on 12 October 2013, retrieved 11 October 2013

Cryptodepression

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Definition and Characteristics

Core Definition

A cryptodepression is a topographic depression in the Earth's crust that extends below mean sea level and is typically occupied by a lake, with the lakebed floor lying subsurface relative to global sea level.[10] This defines the basin's structure independently of the water body's surface elevation, which may be above sea level.[11] Unlike subaerial depressions, which form above sea level and are exposed to the atmosphere, cryptodepressions are characterized by their sub-sea-level basin floor even when filled with water, rendering the depression "hidden" beneath the lake surface.[12] The term derives from the Greek kryptos (hidden) and refers specifically to this concealed subsurface feature in limnological and geomorphological contexts.[13] The concept of cryptodepression entered scientific literature in the early 20th century through geological surveys describing lake basins in Europe, such as those in Prussian territories.[13] Such depressions may relate to broader geological processes like isostatic adjustment, but their definitional essence lies in the below-sea-level morphology.[10]Key Characteristics

Cryptodepressions are distinguished by their basin floors lying at or below mean sea level, typically extending 1-2 meters or more below this datum, with many examples reaching depths of tens to hundreds of meters. For instance, the floor of Vrana Lake on Cres Island reaches 61.3 meters below mean sea level, while Lake Petén Itzá in Guatemala extends 50 meters below, and Lake Maggiore in Italy has bedrock up to 700 meters below.[14][15][12] These depths create isolated depressions that trap water without direct marine influence, setting them apart from lakes at sea level that maintain open hydraulic connections. Hydrologically, cryptodepressions often form freshwater lakes with relatively stable water levels sustained primarily by groundwater inflows through karst or tectonic conduits, rather than surface runoff or tidal exchanges. This isolation prevents widespread saline intrusion, maintaining low salinity levels such as approximately 100 mg/L chloride in Vrana Lake on Cres, though karst permeability can lead to periodic brackish conditions in shallower examples like Velo Blato Lake, where levels fluctuate between 0.5 and 2.36 meters above sea level based on precipitation and subsurface flow.[14][16] Unlike sea-level lakes with dynamic tidal influences, these systems exhibit endorheic or semi-closed behaviors, with minimal surface outlets. Morphologically, cryptodepressions feature steep-sided basins formed in karst, tectonic, or glacial settings, often with high depth-to-width ratios and barriers like ridges separating them from coastal zones. Examples include the narrow karst ridge isolating Vrana Lake on Cres (surface area 5.75 km²) and the doline structure of Velo Blato Lake (2 km²), both lacking visible surface inflows or outflows.[14][16] These traits contribute to enclosed, bowl-like profiles that enhance water retention. Geophysically, cryptodepressions are identified through bathymetric surveys measuring water depths relative to sea level and seismic profiling revealing subsurface bedrock depressions. Bathymetry in Lake Petén Itzá confirmed its 160-meter maximum water depth and 50-meter sub-sea-level extension, while seismic data in similar basins delineate sediment layers and tectonic structures underlying the depressions.[15][17]Geological Formation

Primary Processes

Cryptodepressions form primarily through erosional processes that excavate basins below sea level, often during the Quaternary period. Glacial scouring by ice sheets during the Pleistocene epoch carves deep depressions through abrasion and plucking of bedrock, as seen in northern European lakes where Scandinavian ice lobes intensified erosion. Fluvial incision by rivers erodes valleys and basins over extended periods, deepening floors below sea level in tectonically active or subsiding regions. Karst dissolution in carbonate rock terrains dissolves soluble limestone, creating sinkhole-like cryptodepressions through chemical weathering and collapse, particularly in Mediterranean karst massifs. These erosional mechanisms operate over Quaternary timescales, spanning the Pleistocene to Holocene epochs, with ongoing modifications in glaciated areas.[18][19] Coastal processes, such as post-glacial sea-level rise flooding river valleys impounded by sand dune barrages, also contribute to cryptodepression formation through sediment compaction and barrier stabilization. For example, in Oregon's sand dune lakes, wave action and eolian deposition deepen basins below sea level while maintaining surface water above it.[1] Depositional infilling partially counteracts erosion by accumulating sediments from surrounding highlands, yet maintains the sub-sea-level configuration of the basin floor. Sediments such as glacial tills, varved clays, and fluvio-deltaic deposits fill depressions without fully compensating the excavation, preserving the cryptodepression morphology. In glaciated regions, postglacial isostatic rebound uplifts the crust at rates of up to 10 mm per year (varying by location), tilting basins and influencing sediment distribution, though it does not eliminate the below-sea-level floors formed by prior erosion. Tectonic influences can amplify these processes by providing structural weaknesses that guide erosion along faults.[18][19][20] For example, stratigraphic evidence from core samples in glacial cryptodepressions like Lake Ladoga supports these formation dynamics, revealing layered sediments that indicate prolonged subaerial exposure followed by submergence. Cores show sequences of till overlying pre-Quaternary bedrock, succeeded by limnoglacial varved clays (up to 70 m thick) from ice-marginal lakes, and topped by Holocene lacustrine silts and clays, documenting the transition from erosional dominance to depositional infilling and inundation. Such records confirm the Quaternary evolution, with deglaciation in the late Pleistocene to early Holocene marking the onset of modern basin configurations.[18]Influencing Factors

Tectonic activity significantly influences the development of cryptodepressions by promoting subsidence and faulting that deepen basins below sea level, particularly in rift zones and along plate margins. For instance, the Dead Sea basin exemplifies this process, where the left-lateral strike-slip movement along the Dead Sea Transform fault system has induced ongoing subsidence, resulting in a depression exceeding 400 meters below sea level. This tectonic subsidence, combined with erosional downcutting, has maintained the basin's depth over millions of years despite sediment infilling.[21][22] Isostatic adjustments, driven by the loading and unloading of the Earth's crust, further modulate cryptodepression formation in regions affected by past glaciations. During glacial maxima, the immense weight of ice sheets depresses the crust, creating large-scale basins that can extend below sea level; subsequent post-glacial rebound occurs unevenly, with peripheral forebulges collapsing to sustain low-lying depressions. In proglacial settings, this isostatic depression facilitates the ponding of meltwater into lakes, as observed in models of Laurentide Ice Sheet dynamics where crustal sinking under ice load forms accommodating space for sub-sea-level basins.[23] Climatic influences, especially during the Pleistocene ice ages, accelerate the erosion and shaping of cryptodepressions through intensified periglacial processes such as freeze-thaw cycles and solifluction. These mechanisms enhance mechanical weathering and mass wasting on basin margins, deepening pre-existing tectonic or karstic depressions; for example, Lake Maggiore's cryptodepression, initially formed in the Miocene-Pliocene, was profoundly modified by periglacial modeling during Quaternary glaciations, contributing to its current configuration up to 700 meters below sea level in bedrock.[12] Human activities in the modern era can exacerbate water level fluctuations in existing cryptodepressions, though they do not typically initiate basin formation. Diversion of inflowing rivers and industrial water extraction, such as the Jordan River diversions and potash mining around the Dead Sea, have accelerated the lake's decline by approximately 1 meter per year since the mid-20th century, exposing margins and inducing secondary geological hazards like sinkholes.[24]Types and Classification

Karstic Types

Karstic cryptodepressions represent a subtype of these geological features where basins form primarily through the dissolution of soluble rocks, such as limestone, resulting in sinkholes or poljes that extend below sea level.[2] These depressions arise in karst landscapes characterized by the chemical erosion of carbonate bedrock, creating subsurface voids that propagate to the surface over extended geological timescales.[25] The formation of karstic cryptodepressions involves both hypogene and epigene karstification processes spanning millions of years. Hypogene karstification occurs via ascending aggressive fluids from depth, dissolving rock along fractures to develop extensive conduit networks independent of surface hydrology.[26] In contrast, epigene karstification is driven by downward-percolating meteoric water, which enlarges existing voids and contributes to surface collapse structures, ultimately lowering the basin floor below sea level through repeated dissolution and structural failure.[25] These combined mechanisms produce a hierarchical system of cavities and channels that facilitate the evolution of deep, enclosed depressions.[2] Such features are prevalent in regions with abundant carbonate geology, notably the Dinaric Alps and broader Mediterranean areas, where thick limestone sequences cover vast expanses conducive to intense karst development.[27] The Dinaric Karst, spanning over 60,000 km² of predominantly carbonate rock, exemplifies this prevalence, with cryptodepressions forming due to the region's tectonic stability and high solubility of the bedrock.[28] Karstic cryptodepressions exhibit irregular basin shapes, often elongated or funnel-like, reflecting the anisotropic dissolution patterns in fractured carbonates. They demonstrate high groundwater connectivity through integrated conduit networks linking the basin to regional aquifers and springs. Water levels in these depressions typically fluctuate seasonally, directly responding to precipitation recharge rates and subsurface storage dynamics.[2] In some cases, glacial overprinting may hybridize these forms, modifying surface morphology without altering the primary dissolution origins.[29]Coastal and Dune Types

Coastal cryptodepressions form in dune systems through a combination of post-glacial sea-level rise, sediment compaction, and barrier formation by sand dunes blocking river valleys or lowlands. These features are particularly noted in areas like the Pacific Northwest of the United States, where rising seas flood and deepen basins below sea level.[1] An example is Woahink Lake in Oregon's Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, with a maximum depth of 21 meters, of which 10 meters extend below sea level, created by coastal processes and tectonic influences. These types often exhibit steep walls and are influenced by both marine and fluvial dynamics, distinguishing them from purely karstic or tectonic forms.Tectonic and Glacial Types

Cryptodepressions of tectonic origin arise from the subsidence of fault-block basins or grabens below sea level, primarily driven by rifting or compressional forces along active tectonic margins. These structures develop over extended geological timescales, often spanning the Miocene to Pliocene epochs, as crustal movements create deep, narrow clefts that can reach depths of 2–3 km and persist for millions of years due to the strength of continental crust.[21] A representative example is Lake Matano in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, a tectonic lake hosted within a graben structure formed by strike-slip faulting during the Pliocene, with a maximum depth exceeding 590 m that places portions of its floor approximately 200 m below sea level. These features are typically elongated and rift-like in morphology, often associated with ongoing seismic activity that indicates active plate boundary dynamics.[21] In contrast, glacial cryptodepressions form through the overdeepening of valleys by ice erosion during Pleistocene ice ages, particularly in polar and subpolar regions, where glaciers excavate bedrock below regional base levels over hundreds of thousands to millions of years. The process involves repeated glacial advances that carve U-shaped or linear basins, with post-glacial isostatic depression from the weight of ice sheets sometimes persisting after meltwater retreat due to incomplete crustal rebound.[30] For instance, Lake Geneva in the Western Alps occupies an overdeepened basin reaching 300 m below sea level, shaped by multiple Quaternary glaciations since the Middle Pleistocene (approximately 0.87 million years ago), with the current lake floor reflecting enhanced subglacial erosion during the Last Glacial Maximum around 21–19 ka.[30] Distinguishing characteristics include U-shaped cross-sections from abrasive ice flow and potential moraine dams, contrasting with the fault-controlled linearity of tectonic types, though some basins like Lago Maggiore exhibit mixed origins with initial Miocene-Pliocene tectonic incision later modified by glacial overdeepening up to 370 m below sea level.[12]Notable Examples

European Examples

One prominent example of a cryptodepression in Europe is Lake Skadar, shared between Montenegro and Albania, which is the largest lake in the Balkan Peninsula with a surface area of approximately 370 km².[31] The lake occupies a karst-tectonic hybrid basin where parts of the lakebed extend below sea level, with the southern part approximately 2 meters below sea level and underwater dolines reaching up to 66 meters below sea level, influenced by subterranean karst inflows and tectonic subsidence.[5][32] Red Lake near Imotski, Croatia, is a striking karst-formed cryptodepression in a sinkhole, with a total depth from the rim of 528.9 meters and the deepest point of the basin floor reaching 6 meters below sea level, sustained by an underground conduit system linked to the regional aquifer.[2] Vrana Lake, located in Dalmatia, Croatia, exemplifies a karstic cryptodepression with its basin extending to a depth of 61.3 meters below mean sea level.[33] Formed within a Miocene karst polje, the lake maintains hydrological connections to the Adriatic Sea through underground channels, allowing periodic water exchange that sustains its level despite low surface inflows. This structure highlights the role of coastal karst processes in shaping such depressions, with the lake's surface area covering about 5.8 km².[9][34] In the Alpine region, Lake Maggiore, straddling Italy and Switzerland, represents a glacial-tectonic cryptodepression in an Alpine foreland basin, with portions of its bed reaching approximately 200 meters below sea level due to post-Pliocene glacial scouring and tectonic downwarping.[35] The lake's maximum depth exceeds 370 meters, and its evolution reflects Miocene-Pliocene basin formation modified by Quaternary glaciations, covering a surface area of 212 km².[36]| Lake | Location | Maximum Depth Below Sea Level | Surface Area (km²) | Formation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lake Skadar | Montenegro/Albania | up to 66 m | 370 | Karst-tectonic hybrid |

| Red Lake | Croatia | 6 m | ~0.3 | Karstic |

| Vrana Lake | Croatia | 61.3 m | 5.8 | Karstic |

| Lake Maggiore | Italy/Switzerland | ~200 m | 212 | Glacial-tectonic |