Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cube root

View on WikipediaIn mathematics, a cube root of a number x is a number that has the given number as its third power; that is The number of cube roots of a number depends on the number system that is considered.

Every real number x has exactly one real cube root that is denoted and called the real cube root of x or simply the cube root of x in contexts where complex numbers are not considered. For example, the real cube roots of 8 and −8 are respectively 2 and −2. The real cube root of an integer or of a rational number is generally not a rational number, neither a constructible number.

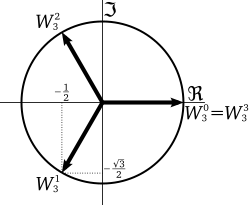

Every nonzero real or complex number has exactly three cube roots that are complex numbers. If the number is real, one of the cube roots is real and the two other are nonreal complex conjugate numbers. Otherwise, the three cube roots are all nonreal. For example, the real cube root of 8 is 2 and the other cube roots of 8 are and . The three cube roots of −27i are and The number zero has a unique cube root, which is zero itself.

The cube root is a multivalued function. The principal cube root is its principal value, that is a unique cube root that has been chosen once for all. The principal cube root is the cube root with the largest real part. In the case of negative real numbers, the largest real part is shared by the two nonreal cube roots, and the principal cube root is the one with positive imaginary part. So, for negative real numbers, the real cube root is not the principal cube root. For positive real numbers, the principal cube root is the real cube root.

If y is any cube root of the complex number x, the other cube roots are and

In an algebraically closed field of characteristic different from three, every nonzero element has exactly three cube roots, which can be obtained from any of them by multiplying it by either root of the polynomial In an algebraically closed field of characteristic three, every element has exactly one cube root.

In other number systems or other algebraic structures, a number or element may have more than three cube roots. For example, in the quaternions, a real number has infinitely many cube roots.

Definition

[edit]The cube roots of a number x are the numbers y which satisfy the equation

Properties

[edit]Real numbers

[edit]For any real number x, there is exactly one real number y such that . Indeed, the cube function is increasing, so it does not give the same result for two different inputs, and covers all real numbers. In other words, it is a bijection or one-to-one correspondence.

That is, one can define the cube root of a real number as its unique cube root that is also real. With this definition, the cube root of a negative number is a negative number.

However this definition may be confusing when real numbers are considered as specific complex numbers, since, in this case the cube root is generally defined as the principal cube root, and the principal cube root of a negative real number is not real.

If x and y are allowed to be complex, then there are three solutions (if x is non-zero) and so x has three cube roots. A real number has one real cube root and two further cube roots which form a complex conjugate pair. For instance, the cube roots of 1 are:

The last two of these roots lead to a relationship between all roots of any real or complex number. If a number is one cube root of a particular real or complex number, the other two cube roots can be found by multiplying that cube root by one or the other of the two complex cube roots of 1.

Complex numbers

[edit]

For complex numbers, the principal cube root is usually defined as the cube root that has the greatest real part, or, equivalently, the cube root whose argument has the least absolute value. It is related to the principal value of the natural logarithm by the formula

If we write x as

where r is a non-negative real number and lies in the range

- ,

then the principal complex cube root is

This means that in polar coordinates, we are taking the cube root of the radius and dividing the polar angle by three in order to define a cube root. With this definition, the principal cube root of a negative number is a complex number, and for instance will not be −2, but rather

This difficulty can also be solved by considering the cube root as a multivalued function: if we write the original complex number x in three equivalent forms, namely

The principal complex cube roots of these three forms are then respectively

Unless x = 0, these three complex numbers are distinct, even though the three representations of x were equivalent. For example, may then be calculated to be −2, , or .

This is related with the concept of monodromy: if one follows by continuity the function cube root along a closed path around zero, after a turn the value of the cube root is multiplied (or divided) by

Impossibility of compass-and-straightedge construction

[edit]Cube roots arise in the problem of finding an angle whose measure is one third that of a given angle (angle trisection) and in the problem of finding the edge of a cube whose volume is twice that of a cube with a given edge (doubling the cube). In 1837 Pierre Wantzel proved that neither of these can be done with a compass-and-straightedge construction.

Numerical methods

[edit]Newton's method is an iterative method that can be used to calculate the cube root. For real floating-point numbers this method reduces to the following iterative algorithm to produce successively better approximations of the cube root of a:

The method is simply averaging three factors chosen such that

at each iteration.

Halley's method improves upon this with an algorithm that converges more quickly with each iteration, albeit with more work per iteration:

This converges cubically, so two iterations do as much work as three iterations of Newton's method. Each iteration of Newton's method costs two multiplications, one addition and one division, assuming that 1/3a is precomputed, so three iterations plus the precomputation require seven multiplications, three additions, and three divisions.

Each iteration of Halley's method requires three multiplications, three additions, and one division,[1] so two iterations cost six multiplications, six additions, and two divisions. Thus, Halley's method has the potential to be faster if one division is more expensive than three additions.

With either method a poor initial approximation of x0 can give very poor algorithm performance, and coming up with a good initial approximation is somewhat of a black art. Some implementations manipulate the exponent bits of the floating-point number; i.e. they arrive at an initial approximation by dividing the exponent by 3.[1]

Also useful is this generalized continued fraction, based on the nth root method:

If x is a good first approximation to the cube root of a and , then:

The second equation combines each pair of fractions from the first into a single fraction, thus doubling the speed of convergence.

Appearance in solutions of third and fourth degree equations

[edit]Cubic equations, which are polynomial equations of the third degree (meaning the highest power of the unknown is 3) can always be solved for their three solutions in terms of cube roots and square roots (although simpler expressions only in terms of square roots exist for all three solutions, if at least one of them is a rational number). If two of the solutions are complex numbers, then all three solution expressions involve the real cube root of a real number, while if all three solutions are real numbers then they may be expressed in terms of the complex cube root of a complex number.

Quartic equations can also be solved in terms of cube roots and square roots.

History

[edit]The calculation of cube roots can be traced back to Babylonian mathematicians from as early as 1800 BCE.[2] In the fourth century BCE Plato posed the problem of doubling the cube, which required a compass-and-straightedge construction of the edge of a cube with twice the volume of a given cube; this required the construction, now known to be impossible, of the length .

A method for extracting cube roots appears in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, a Chinese mathematical text compiled around the second century BCE and commented on by Liu Hui in the third century CE.[3] The Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria devised a method for calculating cube roots in the first century CE. His formula is again mentioned by Eutokios in a commentary on Archimedes.[4] In 499 CE Aryabhata, a mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy, gave a method for finding the cube root of numbers having many digits in the Aryabhatiya (section 2.5).[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "In Search of a Fast Cube Root". metamerist.com. 2008. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013.

- ^ Saggs, H. W. F. (1989). Civilization Before Greece and Rome. Yale University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-300-05031-8.

- ^ Crossley, John; W.-C. Lun, Anthony (1999). The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art: Companion and Commentary. Oxford University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-19-853936-0.

- ^ Smyly, J. Gilbart (1920). "Heron's Formula for Cube Root". Hermathena. 19 (42). Trinity College Dublin: 64–67. JSTOR 23037103.

- ^ Aryabhatiya Archived 15 August 2011 at archive.today Marathi: आर्यभटीय, Mohan Apte, Pune, India, Rajhans Publications, 2009, p. 62, ISBN 978-81-7434-480-9

External links

[edit]Cube root

View on GrokipediaBasics

Definition

The cube root of a number is a number such that .[4] This defines the cube root as the inverse operation to raising a number to the third power, or cubing.[5] The cube root function can be defined over the real numbers or the complex numbers. In the real domain, every real number —whether positive, negative, or zero—has a unique real cube root. For example, \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{8} = 2 because ; \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{-27} = -3 because ; and \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{0} = 0 because .[4][6] The term "cube root" originates from the geometric concept of cubing, where raising a length to the third power corresponds to the volume of a cube with that side length.[7] It is commonly notated as \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} or .[5]Notation and Principal Value

The cube root of a number is commonly denoted using the radical symbol \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} or the exponential form .[4] These notations represent the inverse operation to cubing, where the result satisfies .[4] For real numbers, the principal cube root is defined as the unique real number such that , with when and when . This convention ensures the cube root function is well-defined and continuous over all real numbers, preserving the sign of the input. In the complex domain, the cube root function is multi-valued, with every nonzero complex number having three distinct cube roots differing by factors of the primitive cube roots of unity, and .[8] To define a single-valued principal branch, the argument of the root is restricted to the interval , with a branch cut typically along the negative real axis.[8] This principal value is obtained via , where is the principal logarithm with argument in .[8] For example, the principal cube root of 1 is the real value 1, while the other two roots are the complex numbers and .[4]Properties

Real Cube Roots

Every real number has exactly one real cube root, meaning for any , there exists a unique such that .[9][4] The cube root function f(x) = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} is strictly increasing on , so if , then \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{a} > \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{b}, and it is continuous everywhere on the real line.[9][10][11] The graph of y = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} is an odd function, satisfying for all real , which implies point symmetry about the origin; it passes through (0,0) and exhibits asymptotic behavior where, as becomes large, approaches but grows more slowly than linearly, consistent with the scaling.[9][10] Key identities for real cube roots include the multiplicative property \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{xy} = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} \cdot \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{y} for all real , and the quotient property \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x/y} = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} / \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{y} for ; additionally, \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x^3} = x holds for every real .[9] For , \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} > 0, while for , \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} < 0, preserving the sign of the input.[9] As the inverse of the cubing function , which is bijective from to , the cube root function is also bijective from to .[4][10][12]Complex Cube Roots

In the complex plane, every nonzero complex number has exactly three distinct cube roots, which are the solutions to the equation . To find these roots, express in polar form as , where and . The three cube roots are then given by with denoting the unique positive real cube root of ./06%3A_Complex_Numbers/6.03%3A_Roots_of_Complex_Numbers)[4] The principal cube root is conventionally selected as the one corresponding to , where the argument lies in the principal range , ensuring continuity except across a branch cut. This branch cut is typically placed along the negative real axis to align with the principal branch of the complex logarithm, from which the cube root is derived as \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{z} = \exp\left(\frac{1}{3} \Log z\right), where is the principal logarithm with imaginary part in .[4][8] For the principal cube root \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{z}, the magnitude satisfies |\sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{z}| = |z|^{1/3}, preserving the scaling from the polar representation, while the argument satisfies \arg(\sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{z}) = \arg(z)/3 modulo adjustments to stay within the principal branch. These properties follow directly from the exponential form and ensure that the principal root aligns with the positive real cube root when is positive real./06%3A_Complex_Numbers/6.03%3A_Roots_of_Complex_Numbers)[4] In the context of solving cubic equations with real coefficients, the casus irreducibilis arises when the cubic has three real roots but the Cardano formula involves intermediate complex cube roots, even though the final roots are real; this necessitates using non-real cube roots to express the solutions via radicals.[13][14] A notable example is the cube roots of unity, which solve and are , where is a primitive cube root of unity satisfying and . These roots lie at the vertices of an equilateral triangle in the complex plane and illustrate the multi-valued nature of complex roots.[4]Geometric and Constructibility Aspects

Classical Construction Impossibility

The Delian problem, one of the three classical problems of ancient Greek geometry, requires constructing the edge of a cube with twice the volume of a given cube using only a compass and straightedge.[15] This task is equivalent to constructing a line segment of length \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2} times the length of the given edge, assuming the original edge has unit length.[16] In 1837, Pierre Wantzel proved the impossibility of solving the Delian problem—and more generally, constructing \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{a} for any that is not a perfect cube—using only compass and straightedge.[17] Wantzel's theorem establishes that a real number is constructible if and only if it lies in a field extension of the rationals whose degree is a power of 2.[18] Compass and straightedge operations correspond to adjoining square roots, yielding successive quadratic extensions and thus degrees that are powers of 2.[19] The cube root \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2} generates a field extension \mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2}) over of degree 3, since the minimal polynomial is irreducible over .[19] This degree 3 is not a power of 2, so \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2} cannot lie in any tower of quadratic extensions starting from , rendering it non-constructible.[19] More broadly, adjoining a cube root \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{a} (where is not a perfect cube) produces an extension of degree 3, which is incompatible with the degree constraints of constructible fields.[20] Ancient mathematicians attempted solutions using tools beyond compass and straightedge, such as curves and mechanical devices, but these violated the classical restrictions. For instance, in the 4th century BCE, Menaechmus constructed \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2} using intersecting conic sections (a parabola and hyperbola).[15] Later, Nicomedes (c. 180 BCE) employed his conchoid curve, while Diocles (c. 180 BCE) used the cissoid of Diocles, both allowing exact geometric solutions outside Euclidean rules.[15] Exact constructions of cube roots require non-classical tools like conic sections or a marked ruler for neusis (sliding and rotating a ruler with fixed marks to align points).[15] With a marked ruler, the Delian problem becomes solvable via neusis, as it permits insertions equivalent to solving cubic equations geometrically.[21]Geometric Interpretations

The cube root of a number , denoted \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x}, geometrically represents the side length of a cube whose volume is . For instance, if a cube has a volume of 8 cubic units, its edge length is \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{8} = 2 units, providing a direct spatial interpretation of the operation as reversing the cubing process in three dimensions. This interpretation extends to volume scaling in geometry: when linear dimensions of similar figures are scaled by a factor , their volumes scale by , so the inverse scaling factor for lengths is the cube root of the volume ratio. For example, to find the linear scale factor between two similar cubes with volumes and , compute \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{V_2 / V_1}, illustrating how cube roots quantify dimensional changes in spatial transformations.[22] In coordinate geometry, the cube root function y = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} produces a curve that passes through the origin and is defined for all real numbers, differing from the square root's domain restriction to non-negative inputs. In 2D plots, the graph of y = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} is the reflection of the graph of the cubic function over the line , highlighting their inverse relationship; extending to 3D, surfaces like z = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x^3 + y^3} reveal rotational symmetries around axes.[23] Beyond classical methods, cube roots can be constructed geometrically using origami via the Huzita–Hatori axioms, which enable solving cubic equations through sequential folds aligning points and lines, such as the sixth axiom for trisecting angles or duplicating cubes. Similarly, intersections of conic sections, as demonstrated by Menaechmus for doubling the cube, allow construction of lengths like \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2} by solving the relevant cubic geometrically.[24][25] In crystallography, cube roots appear in determining lattice parameters for cubic crystal structures, where the unit cell volume relates the side length to atomic density via a = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{V}; for body-centered cubic lattices, adjustments like \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2 \bar{v}} (with as volume per atom) refine parameters from experimental densities.[26]Role in Polynomial Equations

Cubic Equations

Cubic equations of the form can be reduced to the depressed cubic through the substitution , eliminating the quadratic term.[27] The explicit solution to this depressed form, known as Cardano's formula, expresses the roots using cube roots: one root is given by y = \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{-\frac{q}{2} + \sqrt{\left(\frac{q}{2}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{p}{3}\right)^3}} + \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{-\frac{q}{2} - \sqrt{\left(\frac{q}{2}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{p}{3}\right)^3}}, with the other two roots obtained by multiplying the cube roots by the non-real cube roots of unity.[27] This formula, first published by Gerolamo Cardano in 1545, provides a closed-form solution for any cubic equation with real or complex coefficients.[14] The nature of the roots depends on the discriminant : if , there is one real root and two complex conjugate roots; if , all roots are real with at least two equal; if , there are three distinct real roots.[28] In the case , the expression under the square root is positive, yielding real cube roots that sum to the real root. However, when and the cubic is irreducible over the rationals—meaning it has no rational roots despite three real ones—the Cardano formula requires taking cube roots of complex numbers, a situation known as the casus irreducibilis.[29] This necessitates complex arithmetic even for real solutions, as demonstrated by François Viète in his geometric and trigonometric approaches to resolving the apparent paradox.[30] A classic example is the equation , which has , , and , indicating three real roots. Applying Cardano's formula yields cube roots of the complex numbers and , whose sum simplifies to the real root ; the other roots are and .[31] To avoid complex numbers in the three real roots case (, ), Viète's trigonometric solution provides an alternative: the roots are This method uses the triple-angle formula for cosine, expressing the roots directly in terms of real trigonometric functions.[28][30]Quartic Equations

The solution of general quartic equations relies on reducing the problem to solving a cubic equation, whose roots are expressed using cube roots, thereby incorporating cube roots into the overall radical expression for the quartic roots. In 1540, Lodovico Ferrari developed a method to solve the general quartic equation by first depressing it—eliminating the cubic term through a substitution for the general form —yielding the depressed quartic . Ferrari's approach then introduces a parameter such that the equation becomes a perfect square plus a linear term, leading to the resolvent cubic equation in : Solving this cubic via Cardano's formula provides the necessary , and the quartic roots are subsequently obtained as where the square roots are taken over the cube root solutions from the resolvent, ensuring the expressions nest cube roots within square roots.[32][33] A representative example illustrates this process for the depressed quartic , where , , . The resolvent cubic simplifies to , with roots ; selecting (a positive real root for the method), the solutions involve square roots of these values, but in the general case, the cubic roots would require cube roots as per Cardano's formula. This demonstrates how cube roots from the resolvent enable algebraic closure for the quartic, yielding exact roots such as and (with signs).[32] René Descartes independently devised a simpler method around 1637, also reducing the depressed quartic to a resolvent cubic by assuming a factorization into quadratics , which yields the same cubic relation for as in Ferrari's approach, again relying on cube roots for resolution.[33] While higher-degree polynomials, such as quintics, generally require transcendental functions like elliptic integrals for their solutions due to the unsolvability by radicals (Abel-Ruffini theorem), cube roots remain central to the radical-based solvability of quartics.Computational Methods

Analytical Approximations

Analytical approximations for the cube root function provide explicit, non-iterative formulas suitable for estimation in specific ranges, often derived from series expansions or rational functions. These methods are particularly useful for real positive arguments where high precision is needed without computational loops. The binomial series expansion offers a power series approximation for the cube root near unity. For small |u| < 1, the cube root can be expressed as ∛(1 + u) = (1 + u)^{1/3} ≈ 1 + \frac{1}{3}u - \frac{1}{9}u^2 + \frac{5}{81}u^3 - \frac{10}{243}u^4 + \cdots, where the general term follows the generalized binomial coefficient \binom{1/3}{k} u^k with \binom{r}{k} = \frac{r(r-1)\cdots(r-k+1)}{k!}. This series converges absolutely for |u| < 1 and provides increasing accuracy as more terms are included, building on the Taylor expansion of the function around u = 0. Linear rational approximations, such as tuned fractional linear forms, extend this utility to broader intervals like [0, a]. These are essentially low-order Padé approximants, rational functions that match the Taylor series up to a certain degree while improving convergence outside the unit disk.[34] Higher-order Padé approximants enhance accuracy by using rational functions P_m(x)/Q_n(x) that agree with the binomial series up to order m + n. For the cube root, [1/2] or [2/1] approximants, derived from the series coefficients, yield errors below 10^{-4} in targeted intervals like [0.07, 13] for suitably chosen degrees. The biroot method constructs such approximants combinatorially, achieving mean errors of 0.035 with standard deviation 0.021 over [0, 10^8] using an [35]-degree Gaussian form for n=3.[34] Error analysis for these approximations relies on remainder estimates. For the binomial series truncated after k terms, the Lagrange remainder provides a bound: |R_k(u)| ≤ \frac{M}{(k+1)!} |u|^{k+1}, where M is an upper bound on the (k+1)-th derivative of (1 + u)^{1/3} over the interval, ensuring the error decreases rapidly for |u| < 1. For Padé and rational forms, errors are bounded by the deviation from the series tail, often < 10^{-6} for degrees ≥ 16 over [0, 100].[36][34]Iterative Algorithms

Iterative algorithms for computing cube roots involve repeated applications of a formula to refine an initial approximation until a desired precision is achieved. These methods solve the equation for the real cube root of a positive number , with extensions for negative values. They are particularly useful in numerical computation where closed-form solutions are unavailable or inefficient.[37] The Newton-Raphson method, also known as the Newton method, is a widely used iterative technique for root-finding that exhibits quadratic convergence when the initial guess is sufficiently close to the root. For cube roots, the iteration is given by where is an initial approximation. This formula arises from applying Newton's method to , using the derivative . The method doubles the number of correct digits per iteration under suitable conditions, making it efficient for high precision.[38][37] Halley's method provides a higher-order alternative with cubic convergence, requiring the second derivative and thus more computation per step but faster overall for many iterations. For cube roots, the iteration simplifies to derived from the general Halley formula using , , and . Introduced by Edmund Halley in 1694, it triples the number of correct digits per iteration near the root, outperforming Newton-Raphson in convergence speed for smooth functions like the cubic.[39][37] Bracketed methods like the bisection method can be adapted for cube roots by solving on an interval where and , repeatedly halving the interval based on the sign of at the midpoint. For , a suitable interval is , yielding linear convergence with the error halving each step, guaranteeing convergence but slower than higher-order methods. The secant method, a derivative-free variant, uses linear interpolation between two initial guesses and to approximate the root, updating via also achieving superlinear convergence (order approximately 1.618) without derivatives, though it may fail without bracketing. Both are robust for initial guesses far from the root but converge linearly or near-linearly.[40]/02%3A_Root_Finding/2.03%3A_Secant_Method) For real , a common convergence criterion is to iterate until for a tolerance , such as , starting with to ensure proximity. For negative , compute the positive cube root of and negate the result, as the real cube root function is odd: \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{-a} = -\sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{a}. These methods assume a real-valued principal root and may require adjustments for complex cases.[38][41] As an example, consider computing \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{2} to five decimal places using the Newton-Raphson method with : After three iterations, the approximation stabilizes at 1.25992, accurate to five decimals (true value ). Analytical approximations can serve as improved initial guesses to accelerate convergence.[42][41]Historical Context

Ancient Origins

The earliest known engagements with cube roots appear in ancient Babylonian mathematics around 2000 BCE, where clay tablets from sites like Senkerra document tables of cubes for numbers up to 32, facilitating practical computations in areas such as volume and inheritance problems.[43] These tablets reflect an empirical approach to handling cubic quantities, often embedded in geometric and administrative contexts, though explicit general methods for root extraction were limited to specific cases derived from solving rudimentary cubic equations.[44] Babylonian scribes employed iterative techniques akin to modern approximations for cube roots in problem-solving, underscoring their focus on numerical utility rather than abstract theory.[45] In ancient Greece, the concept of cube roots gained prominence through the Delian problem, a legendary challenge from around 430 BCE attributed to an oracle at Delos demanding the duplication of a cube's volume to avert a plague.[15] This problem, which required constructing a cube with twice the volume of a given cube using only straightedge and compass, highlighted the need for extracting the cube root of 2 geometrically. Hippocrates of Chios, active circa 470–410 BCE, made the first significant advance by reducing the task to finding two mean proportionals between a line segment and its double, and he explored solutions using lunes—curved segments on spheres—to approximate the required length, though without achieving a full construction.[46] Meanwhile, in China, the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, compiled around 100 BCE, provided systematic algorithms for extracting cube roots as part of its fourth chapter on "diminishing the width," employing a digit-by-digit method on the counting surface similar to long division.[47] This approach allowed for practical approximations of cube roots in engineering and surveying problems, representing one of the earliest documented procedural techniques for the operation. In India, Aryabhata's Āryabhaṭīya from 499 CE introduced a concise rule for cube root extraction through a digit-by-digit process, dividing the number into groups of three digits and iteratively determining each root digit by solving for adjustments in the remainder, akin to contemporary manual methods.[48] These ancient developments remained largely empirical and geometric, laying the foundation for later algebraic advancements in the Islamic world and medieval Europe.[15]Development in Algebra

Islamic and Medieval Contributions

During the Islamic Golden Age, significant progress was made in cube root extraction and solving cubic equations. The earliest known Arabic work on the subject was by al-Uqlīdisī in his 952 treatise The Book of Chapters on Indian Numerals, which detailed procedures using dust boards for computing cube roots digit by digit.[47] Omar Khayyam (1048–1131) advanced geometric methods for solving general cubic equations by intersecting conic sections, effectively extracting cube roots through intersection points.[49] In the 15th century, Jamshīd al-Kāshī (d. 1429) provided refined iterative algorithms for extracting square, cube, and higher roots in his Key to Arithmetic (1427), building on Chinese and Persian traditions and emphasizing practical computation.[50][47] These Islamic innovations were transmitted to Europe through translations, influencing medieval mathematics. The anonymous late 12th-century treatise Artis cuiuslibet consummatio documents one of the earliest European methods for cube root extraction, adapting Arabic techniques to explain the process step by step.[47] The development of cube roots in algebra accelerated during the Renaissance with the publication of Girolamo Cardano's Ars Magna in 1545, which presented the first general algebraic solution to cubic equations involving cube roots of both positive and negative quantities, extending to cases that produced complex intermediates despite Cardano's reservations about their meaning.[51] This work formalized the extraction of cube roots as essential to resolving polynomials of degree three, marking a shift from geometric to symbolic methods and establishing cube roots as fundamental operations in higher algebra.[33] Building on Cardano's framework, Rafael Bombelli's L'Algebra in 1572 introduced systematic rules for arithmetic with imaginary numbers to handle the casus irreducibilis, where cubic equations with three real roots require cube roots of complex numbers, thereby validating and operationalizing complex cube roots in algebraic practice.[52][53] Bombelli's approach resolved paradoxes in Cardano's formula by treating imaginary cube roots as legitimate tools, paving the way for their acceptance in solving real-valued problems.[54] In the late 16th century, François Viète advanced alternative expressions for cubic solutions using trigonometric identities, particularly for equations with three real roots, avoiding complex intermediates by relating roots to angles in multiple-angle formulas.[30][55] This method emphasized the geometric underpinnings of algebra while providing real-number expressions involving cube roots derived from cosine identities.[56] The 19th century brought rigorous definitions of cube roots in the complex plane, with mathematicians like Augustin-Louis Cauchy contributing to the analysis of multi-valued functions and establishing the principal branch of the cube root as the one with argument in to ensure continuity and uniqueness in analytic contexts.[57][58] These formalizations integrated cube roots into the broader theory of complex functions, resolving ambiguities in their algebraic manipulation.[59] In the 20th century, cube roots found practical application in early mechanical and electronic calculators through logarithmic identities, such as \log \sqrt{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}{x} = \frac{1}{3} \log x, which simplified computations by reducing root extraction to scalar multiplication and table lookups or slide rule operations.[60][61] This integration highlighted the algebraic efficiency of cube roots in numerical algebra, influencing computational methods until direct algorithmic implementations became standard.[62]References

- The present article studies the problem of doubling the cube, or duplicating the cube, or the Delian problem which are three different names given to the same ...

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{3}]{x}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/10b5f49269a89e6a236d3889889f3a128d83e822)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{x}}={\sqrt[{3}]{r}}\exp \left({\frac {i\theta }{3}}\right).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1b98750564191c9097532704595eaa97dd435633)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{-8}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1042604e3bf8b89ddd4771fcc19dbb36b05ce423)

![{\displaystyle x={\begin{cases}r\exp(i\theta ),\\[3px]r\exp(i\theta +2i\pi ),\\[3px]r\exp(i\theta -2i\pi ).\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/24bbbc0717e25337093a26c26f3e911ab2505219)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{x}}={\begin{cases}{\sqrt[{3}]{r}}\exp \left({\frac {i\theta }{3}}\right),\\{\sqrt[{3}]{r}}\exp \left({\frac {i\theta }{3}}+{\frac {2i\pi }{3}}\right),\\{\sqrt[{3}]{r}}\exp \left({\frac {i\theta }{3}}-{\frac {2i\pi }{3}}\right).\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b70d19b99d4bd3640e90ef97a5295704f825b49a)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{a}}={\sqrt[{3}]{x^{3}+y}}=x+{\cfrac {y}{3x^{2}+{\cfrac {2y}{2x+{\cfrac {4y}{9x^{2}+{\cfrac {5y}{2x+{\cfrac {7y}{15x^{2}+{\cfrac {8y}{2x+\ddots }}}}}}}}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/53b1538138f23bc34e142a7a4fb13ca3c362922d)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9ca071ab504481c2bb76081aacb03f5519930710)