Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Trousers

View on WikipediaThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

Man wearing a pair of trousers | |

| Material | |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Various |

Trousers (British English), slacks, or pants (American, Canadian and Australian English) are an item of clothing worn from the waist to anywhere between the knees and the ankles, covering both legs separately (rather than with cloth extending across both legs as in robes, skirts, dresses and kilts). Shorts are similar to trousers, but with legs that come down only as far as the knee, but may be considerably shorter depending on the style of the garment. To distinguish them from shorts, trousers may be called "long trousers" in certain contexts such as school uniform, where tailored shorts may be called "short trousers" in the UK.

The oldest known trousers, dating to the period between the thirteenth and the tenth centuries BC, were found at the Yanghai cemetery in Turpan, Xinjiang (Tocharia), in present-day western China.[1][2] Made of wool, the trousers had straight legs and wide crotches and were likely made for horseback riding.[3][4] A pair of trouser-like leggings dating back to 3350 and 3105 BC were found in the Austria–Italy border worn by Ötzi. In most of Europe, trousers have been worn since ancient times and throughout the Medieval period, becoming the most common form of lower-body clothing for adult males in the modern world. Breeches were worn instead of trousers in early modern Europe by some men in higher classes of society. Distinctive formal trousers are traditionally worn with formal and semi-formal day attire. Since the mid-twentieth century, trousers have increasingly been worn by women as well.

Jeans, made of denim, are a form of trousers for casual wear widely worn all over the world by people of both genders. Shorts are often preferred in hot weather or for some sports and also often by children and adolescents. Trousers are worn on the hips or waist and are often held up by buttons, elastic, a belt or suspenders (braces). Unless elastic, and especially for men, trousers usually provide a zippered or buttoned fly. Jeans usually feature side and rear pockets with pocket openings placed slightly below the waist band. It is also possible for trousers to provide cargo pockets further down the legs.

Maintenance of fit is more challenging for trousers than for some other garments. Leg-length can be adjusted with a hem, which helps to retain fit during the adolescent and early adulthood growth years. Tailoring adjustment of girth to accommodate weight gain or weight loss is relatively limited, and otherwise serviceable trousers might need to be replaced after a significant change in body composition. Higher-quality trousers often have extra fabric included in the centre-back seam allowance, so the waist can be let out further.

Terminology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2012) |

In Scotland, a type of tartan trousers traditionally worn by Highlanders as an alternative to the Great Plaid and its predecessors is called trews or in the original Gaelic triubhas. This is the source of the English word trousers. Trews are still sometimes worn instead of the kilt at ceilidhs, weddings etc. Trousers are also known as breeks in Scots, the cognate of breeches. The item of clothing worn under trousers is called pants. The standard English form trousers is also used, but it is sometimes pronounced in a manner approximately represented by [ˈtruːzɨrz], as Scots did not completely undergo the Great Vowel Shift, and thus retains the vowel sound of the Gaelic triubhas, from which the word originates.[5]

In North America, Australia and South Africa,[6] pants is the general category term, whereas trousers (sometimes slacks in Australia and North America) often refers more specifically to tailored garments with a waistband, belt-loops, and a fly-front. In these dialects, elastic-waist knitted garments would be called pants, but not trousers (or slacks).[citation needed]

North Americans call undergarments underwear, underpants, undies, or panties (the last are women's garments specifically) to distinguish them from other pants that are worn on the outside. The term drawers normally refers to undergarments, but in some dialects, may be found as a synonym for breeches, that is, trousers. In these dialects, the term underdrawers is used for undergarments. Many North Americans refer to their underpants by their type, such as boxers or briefs.[citation needed]

In Australia, men's underwear also has various informal terms including under-dacks, undies, dacks or jocks. In New Zealand, men's underwear is known informally as undies or dacks.[citation needed]

In India, underwear is also referred to as innerwear.[citation needed]

The words trouser (or pant) instead of trousers (or pants) is sometimes used in the tailoring and fashion industries as a generic term, for instance when discussing styles, such as "a flared trouser", rather than as a specific item. The words trousers and pants are pluralia tantum, nouns that generally only appear in plural form—much like the words scissors and tongs, and as such pair of trousers is the usual correct form. However, the singular form is used in some compound words, such as trouser-leg, trouser-press and trouser-bottoms.[7]

Jeans are trousers typically made from denim or dungaree cloth. In North America skin-tight leggings are commonly referred to as tights.[citation needed]

Types

[edit]There are several different main types of pants and trousers, such as dress pants, jeans, khakis, chinos, leggings, overalls, and sweatpants. They can also be classified by fit, fabric, and other features. There is apparently no universal, overarching classification.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

Prehistory

[edit]

There is some evidence, from figurative art, of trousers being worn in the Upper Paleolithic, as seen on the figurines found at the Siberian sites of Mal'ta and Buret'.[8] Fabrics and technology for their construction are fragile and disintegrate easily, so often are not among artefacts discovered in archaeological sites. The oldest known trousers were found at the Yanghai cemetery, extracted from mummies in Turpan, Xinjiang, western China, belonging to the people of the Tarim Basin;[2] dated to the period between the thirteenth and the tenth century BC and made of wool, the trousers had straight legs and wide crotches, and were likely made for horseback riding.[3][4]

Antiquity

[edit]

Trousers enter recorded history in the sixth century BC, on the rock carvings and artworks of Persepolis,[9][self-published source?] and with the appearance of horse-riding Eurasian nomads in Greek ethnography. At this time, Iranian peoples such as Scythians, Sarmatians, Sogdians and Bactrians among others, along with Armenians and Eastern and Central Asian peoples such as the Xiongnu/Hunnu, are known to have worn trousers.[10][11] Trousers are believed to have been worn by people of any gender among these early users.[12]

The ancient Greeks used the term ἀναξυρίδες (anaxyrides) for the trousers worn by Eastern nations[13] and σαράβαρα (sarabara) for the loose trousers worn by the Scythians.[14] However, they did not wear trousers since they thought them ridiculous,[15][16] using the word θύλακοι (thulakoi), pl. of θύλακος (thulakos) 'sack', as a slang term for the loose trousers of Persians and other Middle Easterners.[17]

Republican Rome viewed the draped clothing of Greek and Minoan (Cretan) culture as an emblem of civilization and disdained trousers as the mark of barbarians.[18] As the Roman Empire expanded beyond the Mediterranean basin, however, the greater warmth provided by trousers led to their adoption.[19] Two types of trousers eventually saw widespread use in Rome: the feminalia, which fit snugly and usually fell to knee length or mid-calf length,[20] and the braccae, loose-fitting trousers that were closed at the ankles.[21] Both garments were adopted originally from the Celts of Europe, although later familiarity with the Persian Near East and the Germanic peoples increased acceptance. Feminalia and braccae both began use as military garments, spreading to civilian dress later, and were eventually made in a variety of materials, including leather, wool, cotton and silk.[22]

Medieval Europe

[edit]Trousers of various designs were worn throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, especially by men. Loose-fitting trousers were worn in Byzantium under long tunics,[23] and were worn by many tribes, such as the Germanic tribes that migrated to the Western Roman Empire in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, as evidenced by both artistic sources and such relics as the fourth-century costumes recovered from the Thorsberg peat bog (see illustration).[24] Trousers in this period, generally called braies, varied in length and were often closed at the cuff or even had attached foot coverings, although open-legged pants were also seen.[25]

By the eighth century there is evidence of the wearing in Europe of two layers of trousers, especially among upper-class males.[26] The under layer is today referred to by costume historians as drawers, although that usage did not emerge until the late sixteenth century. Over the drawers were worn trousers of wool or linen, which in the tenth century began to be referred to as breeches in many places. Tightness of fit and length of leg varied by period, class, and geography. (Open legged trousers can be seen on the Norman soldiers of the Bayeux Tapestry.)[27]

Although Charlemagne (742–814) is recorded to have habitually worn trousers, donning the Byzantine tunic only for ceremonial occasions,[28][29] the influence of the Roman past and the example of Byzantium led to the increasing use of long tunics by men, hiding most of the trousers from view and eventually rendering them an undergarment for many. As undergarments, these trousers became briefer or longer as the length of the various medieval outer garments changed, and were met by, and usually attached to, another garment variously called hose or stockings.[citation needed]

In the fourteenth century it became common among the men of the noble and knightly classes to connect the hose directly to their pourpoints[30] (the padded under jacket worn with armoured breastplates that would later evolve into the doublet) rather than to their drawers. In the fifteenth century, rising hemlines led to ever briefer drawers[31] until they were dispensed with altogether by the most fashionable elites who joined their skin-tight hose back into trousers.[32] These trousers, which we would today call tights but which were still called hose or sometimes joined hose at the time, emerged late in the fifteenth century and were conspicuous by their open crotch which was covered by an independently fastening front panel, the codpiece. The exposure of the hose to the waist was consistent with fifteenth-century trends, which also brought the pourpoint/doublet and the shirt, previously undergarments, into view,[33] but the most revealing of these fashions were only ever adopted at court and not by the general population.[citation needed]

Men's clothes in Hungary in the fifteenth century consisted of a shirt and trousers as underwear, and a dolman worn over them, as well as a short fur-lined or sheepskin coat. Hungarians generally wore simple trousers, only their colour being unusual; the dolman covered the greater part of the trousers.[34]

Europe before the 20th century

[edit]Around the turn of the sixteenth century it became conventional to separate hose into two pieces, one from the waist to the crotch which fastened around the top of the legs, called trunk hose, and the other running beneath it to the foot. The trunk hose soon reached down the thigh to fasten below the knee and were now usually called "breeches" to distinguish them from the lower-leg coverings still called hose or, sometimes stockings. By the end of the sixteenth century, the codpiece had also been incorporated into breeches which featured a fly or fall front opening.[citation needed]

As a modernization measure, Tsar Peter the Great of Russia issued a decree in 1701 commanding every Russian man, other than clergy and peasant farmers, to wear trousers.[35]

Western dress shall be worn by all the boyars, members of our councils and of our court...gentry of Moscow, secretaries...provincial gentry, gosti,[3] government officials, streltsy,[4] members of the guilds purveying for our household, citizens of Moscow of all ranks, and residents of provincial cities...excepting the clergy and peasant tillers of the soil. The upper dress shall be of French or Saxon cut, and the lower dress...--waistcoat, trousers, boots, shoes, and hats--shall be of the German type

During the French Revolution of 1789 and following, many male citizens of France adopted a working-class costume including ankle-length trousers, or pantaloons (named from a Commedia dell'Arte character named Pantalone)[36] in place of the aristocratic knee-breeches (culottes). (Compare sans-culottes.) The new garment of the revolutionaries differed from that of the ancien regime upper classes in three ways:[citation needed]

- it was loose where the style for breeches had most recently been form-fitting

- it was ankle length where breeches had generally been knee-length for more than two centuries

- they were open at the bottom while breeches were fastened

Pantaloons became fashionable in early nineteenth-century England and the Regency era. The style was introduced by Beau Brummell (1778–1840)[37][38][39] and by mid-century had supplanted breeches as fashionable street-wear.[40] At this point, even knee-length pants adopted the open bottoms of trousers (see shorts) and were worn by young boys, for sports, and in tropical climates. Breeches proper have survived into the twenty-first century as court dress, and also in baggy mid-calf (or three-quarter length) versions known as plus-fours or knickers worn for active sports and by young schoolboys. Types of breeches are also still worn today by fencers, baseball and American football players, and by equestrians.[citation needed]

Sailors may[original research?] have played a role in the worldwide dissemination of trousers as a fashion. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, sailors wore baggy trousers known as galligaskins. Sailors also pioneered the wearing of jeans – trousers made of denim.[41] These became more popular in the late nineteenth century in the American West because of their ruggedness and durability.[citation needed]

Starting around the mid-nineteenth century, Wigan pit-brow women scandalized Victorian society by wearing trousers for their work at the local coal mines. They wore skirts over their trousers and rolled them up to their waists to keep them out of the way. Although pit-brow lasses worked above ground at the pit-head, their task of sorting and shovelling coal involved hard manual labour, so wearing the usual long skirts of the time would have greatly hindered their movements.[citation needed]

Medieval Korea

[edit]The Korean word for trousers, baji (originally pajibaji) first appears in recorded history around the turn of the fifteenth century, but pants may have been in use by Korean society for some time. From at least this time pants were worn by both sexes in Korea. Men wore trousers either as outer garments or beneath skirts, while it was unusual for adult women to wear their pants (termed sokgot) without a covering skirt. As in Europe, a wide variety of styles came to define regions, time periods and age and gender groups, from the unlined gouei to the padded sombaji.[42]

Women wearing trousers

[edit]See also: the Laws section below.

In Western society, it was Eastern culture that inspired French designer Paul Poiret (1879–1944) to be one of the first to design pants for women. In 1913, Poiret created loose-fitting, wide-leg trousers for women called harem pants, which were based on the costumes of the popular ballet Sheherazade. Written by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1888, Sheherazade was based on a collection of legends from the Middle East called 1001 Arabian Nights.[43]

In the early twentieth century, women air pilots and other working women often wore trousers. Frequent photographs from the 1930s of actresses Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn in trousers helped make trousers acceptable for women. During World War II, women employed in factories or doing other "men's work" on war service wore trousers when the job demanded it. In the post-war era, trousers became acceptable casual wear for gardening, the beach, and other leisure pursuits. In Britain during World War II the rationing of clothing prompted women to wear their husbands' civilian clothes, including trousers, to work while the men were serving in the armed forces. This was partly because they were seen as practical for work, but also so that women could keep their clothing allowance for other uses. As this practice of wearing trousers became more widespread and as the men's clothing wore out, replacements were needed. By the summer of 1944, it was reported that sales of women's trousers were five times more than the previous year.[44]

In 1919, Luisa Capetillo challenged mainstream society by becoming the first woman in Puerto Rico to wear trousers in public. Capetillo was sent to jail for what was considered to be a crime, but the charges were later dropped.[citation needed]

In the 1960s, André Courrèges introduced long trousers for women as a fashion item, leading to the era of the pantsuit and designer jeans and the gradual erosion of social prohibitions against girls and women wearing trousers in schools, the workplace and in fine restaurants.[citation needed]

In 1969, Rep. Charlotte Reid (R-Ill.) became the first woman to wear trousers in the US Congress.[45]

Pat Nixon was the first American First Lady to wear trousers in public.[46]

In 1989, California state senator Rebecca Morgan became the first woman to wear trousers in a US state senate.[47]

Hillary Clinton was the first woman to wear trousers in an official American First Lady portrait.[48]

Women were not allowed to wear trousers on the US Senate floor until 1993.[49][50] In 1993, Senators Barbara Mikulski and Carol Moseley Braun wore trousers onto the floor in defiance of the rule, and female support staff followed soon after; the rule was amended later that year by Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Martha Pope to allow women to wear trousers on the floor so long as they also wore a jacket.[49][50]

In Malawi women were not legally allowed to wear trousers under President Kamuzu Banda's rule until 1994.[51] This law was introduced in 1965.[52]

Since 2004 the International Skating Union has allowed women to wear trousers instead of skirts in ice-skating competitions.[53]

In 2009, journalist Lubna Hussein was fined the equivalent of $200 when a court found her guilty of violating Sudan's decency laws by wearing trousers.[54]

In 2012 the Royal Canadian Mounted Police began to allow women to wear trousers and boots with all their formal uniforms.[55]

In 2012 and 2013, some Mormon women participated in "Wear Pants to Church Day", in which they wore trousers to church instead of the customary dresses to encourage gender equality within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[56][57] More than one thousand women participated in 2012.[57]

In 2013, Turkey's parliament ended a ban on women lawmakers wearing trousers in its assembly.[58]

Also in 2013, an old bylaw requiring women in Paris, France to ask permission from city authorities before "dressing as men", including wearing trousers (with exceptions for those "holding a bicycle handlebar or the reins of a horse") was declared officially revoked by France's Women's Rights Minister, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem.[59] The bylaw was originally intended to prevent women from wearing the pantalons fashionable with Parisian rebels in the French Revolution.[59]

In 2014, an Indian family court in Mumbai ruled that a husband objecting to his wife wearing a kurta and jeans and forcing her to wear a sari amounts to cruelty inflicted by the husband and can be a ground to seek divorce.[60] The wife was thus granted a divorce on the ground of cruelty as defined under section 27(1)(d) of the Special Marriage Act, 1954.[60]

Until 2016 some female crew members on British Airways were required to wear British Airways' standard "ambassador" uniform, which has not traditionally included trousers.[61]

In 2017, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints announced that its female employees could wear "professional pantsuits and dress slacks" while at work; dresses and skirts had previously been required.[62] In 2018 it was announced that female missionaries of that church could wear dress slacks except when attending the temple and during Sunday worship services, baptismal services, and mission leadership and zone conferences.[63]

In 2019, Virgin Atlantic began to allow its female flight attendants to wear trousers.[64]

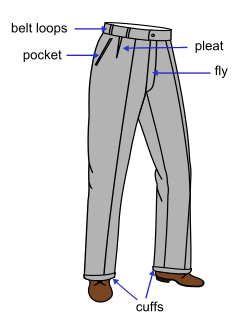

Parts of trousers

[edit]

Pleats

[edit]Pleats are located just below the waistband on the front typify many styles of formal and casual trousers, including suit trousers and khakis. There may be one, two, three, or no pleats, which may face either direction. When the pleats open toward the pockets they are called reverse pleats (typical of most trousers today) and when they open toward the fly they are known as forward pleats.[65]

Pockets

[edit]In modern trousers, men's models generally have pockets for carrying small items such as wallets, keys or mobile phones, but women's trousers often do not – and sometimes have what are called Potemkin pockets, a fake slit sewn shut.[66] If there are pockets, they are often much smaller than in men's clothes.[66] In 2018, journalists at The Pudding found less than half of women's front pockets could fit a thin wallet, let alone a handheld phone and keys.[66][67] 'On average, the pockets in women's jeans are 48% shorter and 6.5% narrower than men's pockets.'[67] This gender difference is usually explained by diverging priorities; as French fashion designer Christian Dior allegedly said in 1954: 'Men have pockets to keep things in, women for decoration.'[67]

Cuffs/Bottom hem

[edit]Trouser-makers can finish the legs by hemming the bottom to prevent fraying. Trousers with turn-ups (cuffs in American English), after hemming, are rolled outward and sometimes pressed or stitched into place.[65]

Fly

[edit]A fly is a covering over an opening join concealing the mechanism, such as a zipper, velcro, or buttons, used to join the opening. In trousers, this is most commonly an opening covering the groin, which makes the pants easier to put on or take off. The opening also allows men to urinate without lowering their trousers.[citation needed]

Trousers have varied historically in whether or not they have a fly. Originally, hose did not cover the area between the legs. This was instead covered by a doublet or by a codpiece. When breeches were worn, during the Regency period for example, they were fall-fronted (or broad fall). Later, after trousers (pantaloons) were invented, the fly-front (split fall) emerged.[68] The panelled front returned as a sporting option, such as in riding breeches, but is now hardly ever used, a fly being by far the most common fastening.[69] Most flies now use a zipper, though button-fly pants continue to be available.[65]

Trouser support

[edit]At present, most trousers are held up through the assistance of a belt which is passed through the belt loops on the waistband of the trousers. However, this was traditionally a style acceptable only for casual trousers and work trousers; suit trousers and formal trousers were suspended by the use of braces (suspenders in American English) attached to buttons located on the interior or exterior of the waistband. Today, this remains the preferred method of trouser support amongst adherents of classical British tailoring. Many men claim this method is more effective and more comfortable because it requires no cinching of the waist or periodic adjustment.[citation needed]

Society

[edit]In modern Western society, males customarily wear trousers and not skirts or dresses. There are exceptions, however, such as the ceremonial Scottish kilt and Greek fustanella, as well as robes or robe-like clothing such as the cassocks of clergy and the academic robes, both rarely worn today in daily use. (See also Men's skirts.)

Among certain groups, low-rise, baggy trousers exposing underwear became fashionable; for example, among skaters and in 1990s hip hop fashion. This fashion is called sagging or, alternatively, "busting slack".[70]

Cut-offs are homemade shorts made by cutting the legs off trousers, usually after holes have been worn in fabric around the knees. This extends the useful life of the trousers. The remaining leg fabric may be hemmed or left to fray after being cut.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Based on Deuteronomy 22:5 in the Bible ("The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man"), some groups, including the Amish, Hutterites, some Mennonites, some Baptists, a few Church of Christ groups, and most Orthodox Jews, believe that women should not wear trousers. These groups permit women to wear underpants as long as they are hidden.[citation needed] By contrast, many Muslim sects approve of pants as they are considered more modest than any skirt that is shorter than ankle length. However, some mosques require ankle length trousers for both Muslims and non-Muslims on the premises.[71]

The Catholic Pope Nicholas I approved of both men and women wearing pants. In 866, he wrote in response to the Bulgar Kahn St Boris the Baptiser, "For whether you or your women wear or do not wear pants neither impedes your salvation nor leads to any increase of your virtue." He then proceeded to expound the virtue of wearing the "spiritual pants" in the form of a temperate life while restraining disordered passions.[72]

Laws

[edit]France

[edit]In 2013, a long-unenforced law requiring women in Paris to ask permission from city authorities before "dressing as men", including wearing trousers (with exceptions for those "holding a bicycle handlebar or the reins of a horse") was declared officially revoked by France's Women's Rights Minister, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem.[59] The bylaw was originally intended to prevent women from wearing the pantalons fashionable with Parisian rebels in the French Revolution.[59]

India

[edit]In 2014, an Indian family court in Mumbai ruled that a husband objecting to his wife wearing a kurta and jeans and forcing her to wear a sari amounts to cruelty inflicted by the husband and can be a ground to seek divorce.[60] The wife was thus granted a divorce on the ground of cruelty as defined under section 27(1)(d) of Special Marriage Act, 1954.[60]

Italy

[edit]In Rome in 1992, a 45-year-old driving instructor was accused of rape. When he picked up an 18-year-old for her first driving lesson, he allegedly raped her for an hour, then told her that if she was to tell anyone he would kill her. Later that night she told her parents and her parents agreed to help her press charges. While the alleged rapist was convicted and sentenced, the Supreme Court of Cassation overturned the conviction in 1998 because the victim wore tight jeans. It was argued that she must have necessarily have had to help her attacker remove her jeans, thus making the act consensual ("because the victim wore very, very tight jeans, she had to help him remove them...and by removing the jeans...it was no longer rape but consensual sex"). The court stated in its decision "it is a fact of common experience that it is nearly impossible to slip off tight jeans even partly without the active collaboration of the person who is wearing them."[73] This ruling sparked widespread feminist protest. The day after the decision, women in the Italian Parliament protested by wearing jeans and holding placards that read "Jeans: An Alibi for Rape". As a sign of support, the California Senate and Assembly followed suit. Soon Patricia Giggans, executive director of the Los Angeles Commission on Assaults Against Women, (now Peace Over Violence) made Denim Day an annual event. As of 2011 at least 20 U.S. states officially recognize Denim Day in April. Wearing jeans on this day, 22 April, has become an international symbol of protest.[citation needed] In 2008 the Supreme Court of Cassation overturned the ruling, so there is no longer a "denim" defense to the charge of rape.[74]

Malawi

[edit]In Malawi, women were not legally allowed to wear trousers under President Kamuzu Banda's rule until 1994.[51] This law was introduced in 1965.[52]

Puerto Rico

[edit]In 1919, Luisa Capetillo challenged mainstream society by becoming the first woman in Puerto Rico to wear trousers in public. Capetillo was sent to jail for what was then considered to be a crime, but, the judge later dropped the charges against her.[citation needed]

Turkey

[edit]In 2013, Turkey's parliament ended a ban on women lawmakers wearing trousers in its assembly.[58]

Sudan

[edit]In Sudan, Article 152 of the Memorandum to the 1991 Penal Code prohibits the wearing of "obscene outfits" in public. This law has been used to arrest and prosecute women wearing trousers. Thirteen women including journalist Lubna al-Hussein were arrested in Khartoum in July 2009 for wearing trousers; ten of the women pleaded guilty and were flogged with ten lashes and fined 250 Sudanese pounds apiece. Lubna al-Hussein considers herself a good Muslim and asserts "Islam does not say whether a woman can wear trousers or not. I'm not afraid of being flogged. It doesn't hurt. But it is insulting." She was eventually found guilty and fined the equivalent of $200 rather than being flogged.[54]

United States

[edit]In May 2004, in Louisiana, Democrat and state legislator Derrick Shepherd proposed a bill that would make it a crime to appear in public wearing trousers below the waist and thereby exposing one's skin or "intimate clothing".[75] The Louisiana bill did not pass.[citation needed]

In February 2005, Virginia legislators tried to pass a similar law that would have made punishable by a $50 fine "any person who, while in a public place, intentionally wears and displays his below-waist undergarments, intended to cover a person's intimate parts, in a lewd or indecent manner". (It is not clear whether, with the same coverage by the trousers, exposing underwear was considered worse than exposing bare skin, or whether the latter was already covered by another law.) The law passed in the Virginia House of Delegates. However, various criticisms to it arose. For example, newspaper columnists and radio talk show hosts consistently said that since most people that would be penalized under the law would be young African-American men, the law would thus be a form of racial discrimination. Virginia's state senators voted against passing the law.[76][77]

In California, Government Code Section 12947.5 (part of the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA)) expressly protects the right to wear pants.[78] Thus, the standard California FEHA discrimination complaint form includes an option for "denied the right to wear pants".[79]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mayke Wagner; Moa Hallgren-Brekenkamp, Dongliang Xu, Xiaojing Kang, Patrick Wertmann, Carol James, Irina Elkina, Dominic Hosner, Christian Leipeg, Pavel E.Tarasovh, "The invention of twill tapestry points to Central Asia: Archaeological record of multiple textile techniques used to make the woollen outfit of a ca. 3000-year-old horse rider from Turfan, China", Archaeological Research in Asia, Volume 29, March 2022, 100344, doi:10.1016/j.ara.2021.100344.

- ^ a b Smith, Kiona N., "The world's oldest pants are a 3,000-year-old engineering marvel", Ars Technica, 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b Beck, Ulrike; Wagner, Mayke; Li, Xiao; Durkin-Meisterernst, Desmond; Tarasov, Pavel E. (22 May 2014). "The invention of trousers and its likely affiliation with horseback riding and mobility: A case study of late 2nd millennium BC finds from Turfan in eastern Central Asia". Quaternary International. 348: 224–235. Bibcode:2014QuInt.348..224B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.04.056. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ a b Beck, Ulrike; Wagner, Mayke; Li, Xiao; Durkin-Meisterernst, Desmond; Tarasov, Pavel E. (2014). "First pants worn by horse riders 3,000 years ago". Quaternary International. 348. Science News: 224–235. Bibcode:2014QuInt.348..224B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.04.056. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "The History and Tradition of Highland Dancing". Historic UK. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Mackenzie, Laurel; Bailey, George; Danielle, Turton (2016). "Our Dialects: Mapping variation in English in the UK". www.ourdialects.uk. University of Manchester. Lexical Variation > Clothing. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Pair of pants". World Wide Words. 28 April 2001. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Nelson, Sarah M. (2004). Gender in archaeology: analyzing power and prestige. Gender and Archaeology. Vol. 9. Rowman Altamira. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7591-0496-9.

- ^ "AS old As a History*". persianwondersvideo.blogspot.com.au.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. pp. 49–51

- ^ Sekunda, Nicholas. The Persian Army 560–330 BC. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Lever, James (1995, 2010). Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson. p. 15.

- ^ ἀναξυρίδες, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ σαράβαρα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Euripides, Cyclops, 182

- ^ Aristophanes, Wasps, 1087

- ^ θύλακος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. p. 50.

- ^ Payne, Blanche (1965). History of Costume. Harper & Row. p. 97

- ^ "Feminalia.", The Fashion Encyclopedia. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Braccae - Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages". Fashionencyclopedia.com. 24 July 2003. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Lever, James (1995, 2010). Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson. p. 40.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 124

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. Pp. 136–138

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. p. 51.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 142

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. pp. 142, 154

- ^ Einhard. The Life of Charlemagne. University of Michigan Press, 1960.

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. pp. 50–51.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 180

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. p. 58.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 207

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 200

- ^ "Pannonian Renaissance". Mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Edicts and Decrees". Cengage Learning. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Italian Culture in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries, ed. Michele Marrapodi 2007

- ^ "Empire/Directoire Image Review-Men". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "History: Regency Origins". Black Tie Guide. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Beau Tie: The Legacy of Beau Brummell, Inventor of the Modern Suit". Mjbale.com. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Gill, Eric (1937). Trousers & The Most Precious Ornament. London: Faber and Faber. OCLC 5034115.

- ^ "The History of Denim". FragranceX. February 2019.

- ^ Lee, Kyung Ja, and Hong Na Young and Chang Sook Hwan, translated by Shin Jooyoung. Traditional Korean Costume. Global Orient, 2003 p. 231.

- ^ "Trousers for Women". Fashionencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Clothing3". World War 2 Ex RAF. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Update: First woman to wear pants on House floor, Rep. Charlotte Reid". The Washington Post. 21 December 2011.

- ^ "First Lady - Pat Nixon | C-SPAN First Ladies: Influence & Image". Firstladies.c-span.org. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "A first: Woman senator dons pants". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 7 February 1989.

- ^ "Flashback: Top 7 Hillary Rodham Clinton pant suits". Rare. 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b Givhan, Robin (21 January 2004). "Moseley Braun: Lady in red". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b "The Long and Short of Capitol Style". Roll Call. 9 June 2005.

- ^ a b Sarah DeCapua, Malawi in Pictures, 2009, pg 7.

- ^ a b "Malawi-vroue mag broek dra" [Malawi: Women may wear pants]. Beeld (in Afrikaans). Johannesburg. 1 December 1993. p. 9. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Slovak Pair Tests New ISU Costume Rules". Skate Today. 5 December 2004. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ a b Gettleman, Jeffrey; Arafat, Waleed (8 September 2009). "Sudan Court Fines Woman for Wearing Trousers". The New York Times.

- ^ Moore, Dene (16 August 2012). "Female Mounties earn right to wear pants and boots with all formal uniforms". The Vancouver Sun. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ Gryboski, Michael (16 December 2013). "Mormon Women Observe 'Wear Pants to Church' Sunday to Promote Gender Equality". Christian Post.

- ^ a b Seid, Natalie (14 December 2013). "LDS Women Suit Up For Second 'Wear Pants to Church Day'". Boise Weekly. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Turkey lifts ban on trousers for women MPs in parliament". Yahoo! News. 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d "It Is Now Legal for Women to Wear Pants in Paris". Time. New York. 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Wife's jeans ban is grounds for divorce, India court rules". Gulf News. Dubai. PTI. 28 June 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Because It Is 2016, British Airways Finally Agrees Female Employees May Wear Pants To Work". ThinkProgress. 6 February 2016.

- ^ Dalrymple II, Jim (30 June 2017). "The Mormon Church Just Allowed Female Employees To Wear Pants. Here's Why That's A Big Deal". Buzzfeed News. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Female Mormon missionaries given option to wear dress slacks". News 95.5 and AM750 WSB. 20 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Yeginsu, Ceylan (5 March 2019). "Virgin Atlantic Won't Make Female Flight Attendants Wear Makeup or Skirts Anymore". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Parts of trousers". ENGLISH FOR TAILORS. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Clark, Pilita (7 November 2022). "Women are big losers in the politics of pockets". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Diehm, Jan; Thomas, Amber (August 2018). "Women's Pockets are Inferior". The Pudding. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Croonborg, Frederick: The Blue Book of Men's Tailoring. Croonborg Sartorial Co. New York and Chicago, 1907. p. 123

- ^ "Button Fly Jeans". www.apparelsearch.com. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Huckaby: Pants off to the kids busting slack at school". Online Athens. 26 August 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Mosque Manners : Dress Code". Szgmc.ae. Archived from the original (JPG) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Murphy, Conrad (23 December 2024). "St. Nicholas I And The Question Of Trousers". Catholic Link. Catholic-Link.org. Archived from the original on 15 January 2025. Retrieved 20 January 2025.

- ^ Faedi, Benedetta (2009). "Rape, Blue Jeans, and Judicial Developments in Italy". Columbia Journal of European Law. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Owen, Richard (23 July 2008). "Italian court reverses 'tight jeans' rape ruling". Irish Independent. Dublin. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "House Bill number 1626" (PDF). Legislature of Louisiana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2004. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

It shall be unlawful for any person to appear in public wearing his pants below his waist and thereby exposing his skin or intimate clothing.

- ^ "Bill Tracking - 2005 session : Legislation". Leg1.state.va.us. 4 February 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "LOCI-HEREIN:A Blog About Today And Tomorrow, With Insights From Yesterday.: 50 bucks to Freeball".

- ^ "California Government Code - GOV § 12947.5". Codes.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Instructions for Obtaining a Right-to-Sue Notice" (PDF). California Department Of Fair Employment & Housing. July 2021. p. 5. DFEH-IF903-7X-ENG. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

I ALLEGE THAT I EXPERIENCED: [...] AS A RESULT I WAS: Denied the right to wear pants

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Trousers at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Trousers at Wikiquote The dictionary definition of trousers at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of trousers at Wiktionary Media related to Trousers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Trousers at Wikimedia Commons- (video) Etymology of 'Pants', from Mysteries of Vernacular Archived 1 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- (video) The Invention of the Trousers, from German Archaeological Institute

Trousers

View on GrokipediaTerminology and Definitions

Etymology and Historical Names

The English term "trousers" derives from the late 16th-century forms "trouzes" (1580s) and "trouse" (1570s), ultimately from Scottish Gaelic triubhas or Middle Irish triubhas, denoting close-fitting shorts or leggings for the lower body that covered each leg separately.[7] [8] This Gaelic root likely influenced the word through Scottish usage, where it referred to tartan-woven, form-fitting leg garments known as trews, worn by Highlanders as an alternative to kilts or plaids.[9] [10] The modern plural "trousers," first attested around 1610, reflects the garment's bipartite structure, with an intrusive "-r-" possibly added by analogy to other plural forms like "drawers."[7] Earlier etymological theories linked it to Old French trebus or Medieval Latin trastrula (breeches), but linguistic evidence favors the Gaelic origin, as triubhas cognates appear in Old Irish tribus for similar legwear.[4] In historical English contexts, precursors to trousers bore names like "breeches" (from Old English brēc, plural for leg-and-trunk garments, evolving to knee-length by the 16th century) or "hose" (Medieval English for fitted leg coverings, often separate or joined at the waist). [11] Scottish "trews" persisted as a synonym into the 18th century, denoting full-length tartan trousers strapped under the foot, while broader variants were called "slops" or "galligaskins" in 16th-17th-century naval and civilian use for loose, protective legwear.[10] These terms distinguished trousers from shorter breeches or undergarments, emphasizing functionality for riding or labor over Roman-influenced togas or tunics.[4]Contemporary Terms and Synonyms

In American English, "pants" serves as the primary contemporary term for the bifurcated outer garment covering the lower body from waist to ankles, encompassing both casual and formal variants, while "trousers" is less common but retained for more formal or tailored styles.[12] [13] In British English, "trousers" is the standard term for this garment, with "pants" strictly denoting underpants or undergarments, a distinction rooted in historical linguistic divergence where American usage shortened "trouser-legs" to "pants" by the 19th century.[14] [15] "Slacks," derived from an Old English term implying looseness, functions as a synonym in American English for semiformal or casual pants, often wool or synthetic, distinct from jeans or denim but overlapping with "dress pants" in professional contexts; it carries a somewhat dated connotation in mid-20th-century usage but persists in retail and apparel descriptions.[16] [15] [17] Regional and informal synonyms include "britches" or "breeches" in Southern or Appalachian American dialects for everyday pants, "strides" in Australian English, and "kecks" as British slang, though these are less prevalent in formal or global contexts.[12] [18] Other less common terms like "denims" refer specifically to material but are sometimes listed as synonyms in thesauruses for broader legwear.[19]Types and Variations

Styles by Fit and Cut

Trousers vary in fit, which determines the closeness to the body from waist to ankle, and in cut, which shapes the leg silhouette. Fits range from tight to loose, while cuts include straight, tapered, bootcut, and wide-leg, influencing both aesthetics and functionality such as ease of movement.[20][21] Skinny fit trousers contour closely to the legs from thigh to ankle, typically with a leg opening under 7 inches, emphasizing a streamlined profile suitable for lean builds but potentially restrictive for broader frames.[20][22] Slim fit provides a tapered silhouette narrower than regular but less extreme than skinny, hugging the thighs and calves while allowing moderate mobility, often with a 7-8 inch leg opening; this style suits athletic or slender physiques without excessive tightness.[20][23][22] Regular or straight fit maintains consistent width from hip to hem, offering balanced roominess with a leg opening around 8-9 inches, prioritizing comfort and versatility across body types without clinging or bagging.[20][21] Relaxed fit features extra fabric in the seat and thighs, tapering slightly or remaining straight-legged, with openings exceeding 9 inches, designed for enhanced comfort in casual or workwear contexts, accommodating larger builds or layered clothing.[20][24] In terms of cut, straight-leg trousers preserve parallel lines from upper leg to ankle, promoting a classic, proportional appearance adaptable to formal and everyday wear.[21][25] Tapered cut starts fuller at the hips and narrows toward the ankle, creating an elongated visual effect while providing thigh room, common in modern slim variants for a polished yet practical form.[26][22] Bootcut styles widen modestly below the knee—typically 1-2 inches more than straight—for accommodating boots, blending fitted upper legs with a subtle flare for equestrian or rugged applications.[27][28] Wide-leg cut, prevalent in both genders' trousers, offers ample volume from hip to hem, with leg openings often 10+ inches, enhancing airflow and a dramatic drape favored in warmer climates or loose silhouettes.[26][29] Flare cut mirrors bootcut but exaggerates the bell-shaped expansion at the hem, historically tied to 1970s trends and revived for elongating shorter torsos, though less common in strict trouser tailoring.[26][30]Functional and Specialized Variants

Functional variants of trousers incorporate specialized features to enhance utility for particular occupations, environments, or activities, prioritizing durability, protection, and accessibility over aesthetic appeal. These designs often include reinforced fabrics, additional pockets, ergonomic elements, or adaptive mechanisms to address specific physical demands, such as mobility on horseback or storage for tools and gear.[31] Cargo trousers, characterized by large flap-covered bellows pockets on the outer thighs, originated in the British Army's 1930s Battle Dress Uniform for soldiers requiring expanded storage for maps, ammunition, and medical supplies during World War II; the design was later adapted by U.S. paratroopers in the 1940s for similar functional needs.[32][33] These pockets, typically four in number with cargo-style expansion, allow secure carriage of bulky items without restricting movement, making them suitable for military, fieldwork, and outdoor pursuits.[34] Workwear trousers are engineered for industrial and trade applications, featuring elements like padded or reinforced knees to prevent injury from kneeling, multiple tool loops and hammer pockets for carpenters, or flame-retardant treatments for welding and manufacturing environments.[35] High-visibility variants incorporate reflective strips and fluorescent fabrics compliant with safety standards such as EN ISO 20471 for construction sites, while waterproof models use membranes like those rated at 10,000mm hydrostatic head for wet trades.[36] Bib-and-brace styles extend coverage to the torso with suspenders, offering enhanced protection against debris and falls in heavy labor.[37] Outdoor recreational trousers, such as convertible hiking models, feature zip-off legs that detach below the knee via inseam zippers, enabling rapid conversion to shorts for temperature regulation during variable conditions; fabrics often provide UPF 50+ sun protection and quick-drying properties, with weights around 8-12 ounces per square yard for breathability.[38][39] Ski pants emphasize weather resistance with fully taped seams, 20,000mm waterproof ratings, and insulation layers of 40-80 grams per square meter, alongside thigh vents for moisture management during high-exertion descents.[40][41] Equestrian breeches are form-fitting from waist to ankle, with suede or synthetic knee patches for friction grip against saddles and high-denier stretch fabrics for unrestricted leg movement; full-seat variants extend silicone printing to the buttocks for added stability in disciplines like dressage.[42] These specialized trousers typically measure 14-18 inches in thigh circumference at the fullest point, balancing compression for muscle support with flexibility for prolonged riding sessions.[43]Materials and Fabrics

Wool has historically served as the foundational material for tailored trousers, prized for its natural durability, insulation properties, and ability to hold a crease, with origins traceable to fine suiting cloths used since at least the 18th century in European tailoring traditions.[44] Its fibers provide resilience against wear, though proper dry cleaning is required to maintain longevity, as improper care can lead to shrinkage or felting.[45] Cotton, derived from the Gossypium plant, dominates casual and workwear trousers for its breathability, softness against the skin, and moisture-wicking capabilities, making it suitable for year-round use in moderate climates.[46] Denim, a sturdy twill weave of cotton, exemplifies this with high tensile strength—often exceeding 50,000 pounds per square inch in warp direction for premium varieties—enabling resistance to abrasion in jeans and chinos.[47] However, pure cotton wrinkles easily and may sag over time without blends.[48] Synthetic fabrics like polyester offer advantages in wrinkle resistance and quick drying, with blends incorporating 20-50% elastane adding stretch for improved mobility in performance trousers.[49] Polyester's durability stems from its petroleum-based polymer structure, resisting pilling and fading better than naturals in high-use scenarios, though it traps heat and odors due to low breathability.[50] Cotton-polyester hybrids combine breathability with shape retention, as seen in workwear where polyester enhances tear strength by up to 30% over pure cotton.[51] Linen and hemp provide lightweight, breathable options for summer trousers, with hemp requiring minimal water (under 500 liters per kilogram versus cotton's 10,000) and exhibiting antimicrobial properties from its bast fibers.[52][53]| Fabric | Key Properties | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wool | Insulating, crease-holding | Durable drape, temperature regulation | Requires dry cleaning, potential shrinkage |

| Cotton/Denim | Breathable, absorbent | Comfortable, versatile for casual wear | Prone to wrinkling, sagging without blends |

| Polyester Blends | Wrinkle-resistant, stretchy | Low maintenance, high abrasion resistance | Poor breathability, retains odors |

| Linen/Hemp | Highly breathable, low-water production | Eco-efficient, antimicrobial | Coarse texture, wrinkles heavily |

Historical Development

Prehistoric and Ancient Origins

The earliest known precursors to trousers appeared in the Neolithic period as separate leg coverings rather than unified garments. Ötzi the Iceman, a Copper Age man preserved in the Ötztal Alps and dated to approximately 3300 BC, wore two unattached leggings crafted from domestic goat hide, each about 65 cm long, secured with a belt and paired with a sheepskin loincloth; these components were not joined at the crotch, distinguishing them from later trousers.[57][58] Such separate leggings likely served practical purposes in cold, rugged terrains, reflecting adaptations for mobility without the full enclosure of trousers. The invention of true trousers—bifurcated garments covering both legs and the lower torso in a single piece—emerged during the late Bronze Age, closely tied to the domestication of horses around 3500 BC and the needs of steppe nomads for equestrian mobility. The oldest surviving example, discovered in 2014 in the Yanghai tombs of China's Tarim Basin, dates to between 1300 and 1000 BC (specifically tombs M21 at 1122–926 BC and M157 at 1261–1041 BC); these wool trousers featured a stepped crotch for riding, drawstrings at the waist and ankles, and bias-cut panels for flexibility, techniques still used in modern tailoring.[59][60] This design's causal link to horseback riding is evident in its anatomical fit, which prevented chafing and binding during prolonged saddle time, a necessity absent in pedestrian societies favoring draped garments.[61] By the Iron Age, trousers spread among Indo-Iranian pastoralists, including Scythians of the Pontic-Caspian steppes (7th–3rd centuries BC), who wore fitted wool or leather variants depicted in art and confirmed by archaeological finds from sites like the Altai Mountains (5th–4th centuries BC).[62] In the Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 BC), trousers known as anaxyrides—often colorful leather breeches tucked into boots—became standard for cavalry and infantry, adopted from eastern nomadic influences for military efficacy on horseback; Greek sources like Herodotus and Xenophon noted their prevalence among Persians and mocked them as effeminate or barbaric sacks, contrasting with Mediterranean tunics.[63] This adoption underscores trousers' utility in mounted warfare, where they enabled greater leg protection and freedom compared to chitons or togas, influencing later Eurasian cultures despite initial disdain in sedentary civilizations.[2]Classical Antiquity and Medieval Periods

In ancient Greece, spanning roughly the 8th to 4th centuries BCE, trousers were absent from standard male attire, which consisted of the short chiton or longer himation draped over the body; such bifurcated leg coverings were derided as the apparel of "barbarians," particularly horse-riding peoples like the Scythians and Persians, whose anaxyrides Herodotus noted in the 5th century BCE as practical for equestrian activities but emblematic of foreign effeminacy and weakness.[64][65] Roman attitudes mirrored Greek disdain during the Republic (509–27 BCE), where the toga symbolized citizenship and trousers, termed bracae and adopted from Celtic Gauls and Germanic tribes, were confined to non-citizens, slaves, or frontier auxiliaries; these woolen, often tight-fitting garments reaching mid-calf or ankle provided protection in colder provinces like Gaul and Britannia.[66][67] By the 3rd century CE, amid military reforms and increased barbarian interactions, Roman legions routinely wore long bracae paired with tunics for practicality in cavalry roles and harsh climates, though urban elites resisted, culminating in Emperor Honorius's 397 CE ban on trousers within Rome to preserve traditional decorum.[66][68] During the Medieval period in Western Europe (c. 500–1500 CE), full-length trousers akin to modern forms remained rare among the general populace, supplanted by braies—linen or woolen underdrawers extending to the knee or mid-thigh—and separate hose or chausses, fitted leg coverings of wool or later mail that laced or pointed to a belt or upper garment for each leg independently, reflecting a continuity of Roman tunica traditions adapted to feudal mobility and armor needs.[69][70] This system prioritized flexibility for horseback and combat over unified trousers, which began emerging in the late 14th century as joined hose among nobility and mercenaries, precursors to Renaissance breeches, while everyday laborers often retained simpler braies exposed beneath tunics.[70] In contrast, Byzantine and Islamic regions preserved fuller trousers like sirwal from Sassanid influences, underscoring cultural divergences in legwear utility.[71]Early Modern to 19th Century

In the early modern period, European men predominantly wore breeches—knee-length garments fastened below the knee and paired with stockings—rather than full-length trousers, which were viewed as utilitarian or barbaric attire associated with sailors, laborers, and non-Western peoples.[71][72] Baggy trousers, known as galligaskins, were worn by 17th- and 18th-century sailors for practicality at sea, marking one of the few contexts where full-length leg coverings gained traction among Europeans.[71] Breeches remained the standard for upper-class men through the 18th century, evolving into tighter fits but retaining their short length to accommodate formal hose and buckles.[73] The shift toward trousers accelerated in the late 18th century amid social and political upheaval, particularly during the French Revolution of 1789, when working-class revolutionaries dubbed sans-culottes rejected aristocratic breeches in favor of practical, full-length pantaloons symbolizing egalitarian simplicity.[74] This adoption spread through military influences, as soldiers encountered trousers in Eastern campaigns and found them superior for riding and mobility.[71] By the Regency era in Britain (circa 1811–1820), pantaloons—form-fitting, ankle-length garments strapped under the foot—emerged for daytime wear among dandies like George "Beau" Brummell, while looser trousers suited informal or outdoor activities; breeches persisted only for evening formalwear until the 1820s.[72][75] Throughout the 19th century, trousers became the normative lower garment for men in Western Europe and North America, standardized by mid-century with features like the fall-front closure for ease of use with braces.[76] In Britain and France, post-Napoleonic military uniforms popularized straight-cut trousers, influencing civilian fashion toward simplicity and functionality over the ornate breeches of prior eras.[71] Variations such as gaitered trousers, with fitted lower legs and buttons for boots, appeared for equestrian and urban use, reflecting adaptations to industrialization and expanded rail travel.[77] Women's wear remained restricted to skirts, with trousers limited to private or reformist contexts until later decades.[74]20th Century Evolution

In the early 20th century, men's trousers evolved from the fitted, high-waisted styles of the preceding era toward looser silhouettes influenced by post-World War I relaxation in social norms and athletic pursuits. By 1924, Oxford bags—characterized by extremely wide legs with hems up to 22 inches—emerged among students at Oxford University as a deliberate circumvention of bans on knickerbockers for rowing, reflecting youthful rebellion and spreading as a jazz-age fashion trend across Britain and beyond.[78][79] The 1930s saw continued popularity of wide-legged trousers often paired with suspenders, prioritizing comfort amid economic depression.[71] Mid-century shifts emphasized slimmer profiles for men, with the 1950s introducing tailored slim-fit trousers alongside the rise of denim jeans as symbols of youthful defiance, propelled by Hollywood icons like James Dean in films such as Rebel Without a Cause (1955).[71][80] The 1960s mod aesthetic favored slim cuts, transitioning to bell-bottoms by decade's end, while the 1970s amplified flares and bold patterns in line with disco culture.[71] Women's adoption accelerated due to practical demands during the World Wars, where trousers enabled factory and field labor, challenging traditional gender attire norms.[81] By the 1950s, slacks gained casual acceptance for recreation, and in 1966, Yves Saint Laurent's Le Smoking tuxedo suit for women marked a haute couture milestone, blending masculine tailoring with feminine empowerment in his Autumn-Winter collection.[82][81] The 1980s power dressing era normalized tailored trousers in professional settings, signifying broader gender equality in fashion by the late century.[71] Denim jeans, initially rugged workwear, transformed into ubiquitous casual trousers, with 1950s teen culture and 1960s counterculture—evident in civil rights protests and hippie movements—elevating them beyond utility to emblems of rebellion and solidarity.[80] The 1970s introduced flared and designer variants, solidifying jeans' role in mainstream fashion evolution.[80][71]21st Century Innovations

In the early 2000s, trouser manufacturers began incorporating advanced synthetic fibers such as Dyneema, a ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene known for its exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, into denim and performance trousers to achieve greater tear resistance and abrasion durability without sacrificing flexibility. Outlier's End of Worlds trousers, launched in 2017, exemplified this by blending Dyneema with cotton for pants capable of withstanding extreme wear, such as repeated machine washes and physical stresses equivalent to thousands of abrasion cycles in laboratory tests.[83] Similarly, four-way stretch fabrics, integrating elastane or spandex with nylon or polyester bases, gained prominence around 2010 for enabling unrestricted movement in athletic and casual trousers, reducing binding at knees and hips during dynamic activities.[84][31] The integration of wearable sensors marked a significant technological shift, with smart trousers emerging to monitor physiological and kinematic data. In 2023, engineers at the University of Missouri developed fiber-optic-based smart pants using bend sensors woven into the fabric, capable of detecting gait abnormalities and fall risks with 95% accuracy in preliminary trials involving elderly subjects, transmitting data wirelessly to caregivers via Bluetooth.[85] The U.S. Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) initiated the SMART ePANTS program in the mid-2010s, funding research into embedding piezoelectric and capacitive sensors directly into trouser fabrics for real-time tracking of joint angles, posture, and vital signs, with prototypes demonstrating integration into everyday cotton-polyester blends without compromising washability or comfort.[86] Commercial examples include Wearable X's Nadi X yoga pants, introduced in 2017, which use embedded haptic motors to deliver targeted vibrations for posture correction during exercise, guided by smartphone apps analyzing sensor inputs. Sustainability-driven innovations focused on material recycling and low-impact production, with trousers increasingly made from regenerated fibers like those derived from post-consumer denim waste. By the 2010s, brands adopted closed-loop systems, such as Levi's Water<Less process refined in 2011, which reduced water usage in jeans finishing by up to 96% through laser etching and ozone foaming instead of traditional stone-washing, extending to broader trouser lines.[88] Expanding waistbands, evolving from elasticated designs in the early 2000s to adaptive mechanisms using memory foams or segmented bands, addressed fluctuating body sizes post-meal or during weight changes, with patents filed around 2010 enabling up to 4 inches of circumferential adjustment while maintaining a tailored silhouette.[89] These developments prioritized empirical performance metrics, such as tensile strength exceeding 500 N/cm² in smart fabrics and lifecycle carbon footprints reduced by 30-50% in recycled variants, verified through standardized textile testing protocols.[31]Design and Components

Basic Structure

The basic structure of trousers comprises two tubular leg sections joined at the crotch seam, forming the bifurcated lower garment that covers the legs and lower torso up to the waist. This core assembly is completed by a waistband that encircles the upper edge, providing closure and support, typically via a fly front opening secured by buttons or a zipper.[90][91] The waistband, often constructed from self-fabric or reinforced material, sits at the natural waist or hips and includes belt loops spaced approximately 2-3 inches apart to accommodate a belt for adjustable fit. Below the waistband lies the rise, measured as the vertical distance from the crotch seam to the waistband top, which varies by style—front rise typically shorter than back rise to accommodate body curvature—and influences overall comfort and silhouette. The crotch area, where front and back panels meet, features a curved seam for ergonomic fit, with crotch depth measured from the waist through the seat to ensure mobility; inadequate depth leads to binding, while excess causes sagging.[90][91][92] Front and back panels are shaped by darts or a yoke in the rear to contour the hips and seat, reducing bulk at the waist while providing ease—typically 1-3 inches at the hips for standard trousers. The fly, a reinforced placket along the front seam, facilitates dressing and is often lined for durability. Pockets integrate into the structure: front slash pockets for accessibility, back welt or flap pockets for security, with linings to prevent sagging.[91][92] Leg construction involves the inseam (inner leg seam from crotch to hem, dictating thigh fit) and outseam (outer side seam from waist to hem), which may curve inward for taper or remain straight for width. The hem finishes the leg openings, either raw, cuffed, or turned under, with circumference varying by style—e.g., straight legs measure consistently, while tapered reduce toward the ankle. Seams throughout, such as side and crotch, are typically flat-felled or overlocked for strength and neatness in production.[90][91][92]Functional Features

The primary functional features of trousers center on facilitating mobility, secure fit, storage, and durability through engineered components. The waistband, a reinforced strip of fabric encircling the waist, provides structural support and stability, often incorporating interfacing to prevent stretching and buckling during wear; it typically measures 1.5 to 2 inches in height for optimal load distribution.[93] [91] Belt loops, evenly spaced along the waistband (usually six to eight), enable the use of a belt to cinch the garment, accommodating variations in body shape and preventing slippage under gravitational or dynamic forces.[94] The fly closure, positioned at the front crotch, employs a zipper, buttons, or hooks to allow efficient dressing while concealing the opening for hygiene and modesty; zippers, introduced widely in the 1930s, reduce friction and enable one-handed operation compared to button flies, which offer adjustability but slower access.[93] [95] Pleats, single or double folds originating from the waistband, expand the seat and thigh area to permit unrestricted hip flexion and extension—essential for activities involving bending or sitting—while collapsing flat to maintain a streamlined profile when standing.[96] This design, rooted in practical tailoring, increases fabric allowance by 1-2 inches per pleat without excess bagginess.[93] Pockets serve as utilitarian storage, with slanted front pockets (quarter or jetted) angled at 10-15 degrees for ergonomic hand insertion and weight distribution, and back pockets reinforced with double stitching or patch construction to withstand pulling forces from carried items.[94] [97] The crotch curve and inseam/outseam seams are contoured to follow the body's natural contours, minimizing binding during leg movement; ergonomic variants include pre-bent knees to align with joint flexion, reducing strain by up to 20% in prolonged wear scenarios.[91] [98] Cuffs (or turn-ups), folded hems adding 1.5-2 inches of fabric weight, serve to shorten effective inseam length, prevent fraying, and promote trouser drape by anchoring the hem against shoe tops, though they reduce mobility in high-stepping activities.[99] In specialized trousers, features like yoke panels at the rear waist enhance contouring over the hips and glutes for better load transfer, while partial linings in the seat area wick moisture and reduce chafing.[94] These elements collectively prioritize causal mechanics of human locomotion and posture, with empirical tailoring standards ensuring longevity exceeding 100 wear cycles under normal use.[91]Fit and Customization

The fit of trousers refers to how the garment conforms to the wearer's body, balancing comfort, mobility, and aesthetics through precise measurements of key dimensions such as waist circumference, rise (the distance from the waistband to the crotch seam), inseam length (from crotch to hem), thigh width, knee width, and leg opening.[100] A proper waist fit sits securely without constriction, typically allowing space for one finger below the belly button at the rise point to follow natural body contours and prevent sagging or binding during movement.[101] Thigh measurements average around 32 cm in circumference for standard adult male proportions, tapering to 24 cm at the knee and 19 cm at the bottom hem, with deviations adjusted to accommodate muscular builds or sedentary frames to avoid restriction.[100] Common fit profiles include slim (narrow through hip to ankle for a streamlined silhouette), tapered (roomier in thighs narrowing to ankles for athletic legs), straight (consistent width for balanced proportions), relaxed (generous throughout for ease), and wide-leg (broad from hip down for volume and flow).[102][22] Inseam lengths are standardized as short (under 30 inches), regular (31-33 inches), or long (34 inches and above) to align with height, while hem breaks—classified as no-break (hem skims shoe top), slight-break (minimal fold), or full-break (pronounced crease)—influence perceived leg length and formality.[103] These variations derive from anthropometric data ensuring functionality, as overly tight fits can impede circulation or stride, whereas loose ones may cause fabric bunching and reduce mobility.[100] Customization elevates fit beyond ready-to-wear (RTW) by tailoring to individual metrics via made-to-measure (MTM) or bespoke processes. In MTM, core adjustments target waist, rise, inseam, and leg opening based on initial body scans or tape measures, often yielding a basted prototype for refinements.[104] Bespoke tailoring, a multi-stage craft originating in Savile Row traditions, begins with comprehensive measurements (over 20 points including seat depth and calf girth), followed by hand-drafted patterns, a loose basted fitting for gross adjustments, a forward fitting in half-lined garment for fine-tuning, and a final pressing.[105] This allows bespoke elements like adjustable waistbands, reinforced pockets, or custom pleats, with fabrics cut to minimize seams and enhance drape, typically requiring 6-8 weeks and costing 2000 depending on materials.[106] Post-purchase alterations for RTW trousers, such as hemming or tapering, can refine fit by 1-2 cm in critical areas but lack the precision of custom construction.[107] Proper customization prioritizes causal factors like body asymmetry—e.g., one leg shorter by 1 cm—or activity demands, such as increased thigh room for cyclists, over generic sizing charts that ignore variances in posture or weight distribution.[108] Empirical fitting trials confirm that deviations exceeding 2 cm in thigh or knee girth lead to discomfort, underscoring the value of iterative fittings in bespoke workflows.[100]Cultural and Social Aspects

Gender Norms and Adoption by Women

In Western societies from antiquity through the 19th century, trousers were codified as male attire, symbolizing authority, mobility, and labor suited to bipedal male physiology, while women adhered to skirts and dresses to denote femininity, modesty, and restricted movement aligned with domestic roles.[6] This binary stemmed from practical distinctions in anatomy and societal division of labor, reinforced by religious and legal customs viewing cross-gender dress as disruptive to natural order and family structure.[109] Early resistance to women's trousers often invoked moral panic, with critics decrying them as harbingers of societal decay or inversion of biblical gender hierarchies.[109] The first notable Western push for female trouser adoption occurred in 1851, when Elizabeth Smith Miller publicly wore the "bloomer" outfit—loose, ankle-length trousers gathered at the ankles beneath a shortened skirt—for greater ease in daily tasks, inspired by practical garments observed on European peasant women.[110] Promoted by Amelia Bloomer in her magazine The Lily starting in 1851, the style aimed at dress reform to alleviate health issues from heavy, restrictive skirts but faced swift backlash: newspapers ridiculed it as unfeminine and mannish, clergy sermons condemned it as immodest, and social ostracism limited uptake to a fringe of reformers.[111] By the 1890s, rational dress societies in Europe and the U.S. advocated bifurcated undergarments for cyclists and workers, yet norms persisted, with trousers equated to prostitution or radicalism in public discourse.[6] World War I (1914–1918) marked pragmatic breakthroughs, as women in munitions factories and farms donned trousers or overalls for safety around machinery and efficiency in physical labor, numbering over 1 million in Britain alone by 1917.[112] Post-war, fashion innovators like Coco Chanel normalized wide-leg trousers in the 1920s for leisure and beachwear, drawing from menswear but tailored for feminine silhouettes, gaining traction among urban elites despite lingering taboos.[113] World War II (1939–1945) accelerated adoption, with 18 million U.S. women entering the workforce by 1944, many in factory "slacks" immortalized by the Rosie the Riveter iconography promoting trousers for patriotic utility.[114] By the 1960s, evolving labor participation and second-wave feminist advocacy eroded resistance, with designers like Yves Saint Laurent introducing the women's tuxedo pant (Le Smoking) in 1966, blending masculinity and elegance for professional wear.[115] Pantsuits became symbols of workplace equality, as evidenced by their mainstreaming in the 1970s when over 50% of U.S. women owned trousers, driven by causal factors including contraceptive access enabling career focus and mechanical innovations like zippers improving fit.[116] Acceptance reflected not mere ideology but empirical advantages in mobility and hygiene, though pockets of opposition lingered in conservative institutions, underscoring trousers' role in visually contesting rigid gender divisions without negating biological sex differences.[117]Religious Perspectives

In Judaism, Orthodox communities generally prohibit women from wearing trousers, interpreting them as kli gever—men's apparel forbidden under Deuteronomy 22:5, which states, "A woman shall not wear a man's garment." This stems from the Torah's broader mandate against cross-dressing to preserve gender distinctions, combined with tzniut (modesty) norms that favor skirts or dresses to conceal leg shape and align with historical Jewish dress codes. Some rabbinic opinions, such as that of Rabbi Yosef Henkin, permit loose trousers in private or non-public settings if they do not resemble men's attire, though community standards in most Haredi and Modern Orthodox groups enforce skirts exclusively in public.[118][119] Christian interpretations of trousers vary widely, often referencing the same Deuteronomy 22:5 verse, but without uniform enforcement. Conservative Protestant denominations, such as certain Pentecostal or fundamentalist groups, view women's trousers as violating the prohibition against adopting "that which pertaineth unto a man," equating pants with masculine attire and associating them with immodesty or role blurring; for instance, some Assemblies of God churches historically banned pants for women until the mid-20th century. Mainstream evangelical and Catholic sources, however, argue the verse targets idolatrous cross-dressing in ancient Canaanite contexts rather than modern garments, permitting trousers if they are modest and do not mimic male styles—emphasizing 1 Timothy 2:9's call for "modest apparel" over specific prohibitions.[120][121] In Islam, trousers for women are frequently deemed impermissible (haram) in public or mixed settings, as they outline the legs' form, contravene awrah (parts requiring covering from navel to knees for women before non-mahram men), and imitate male dress prohibited by hadiths such as "The Prophet cursed effeminate men and those women who assume the similitude (manners) of men." Salafi and Hanbali scholars, like those on IslamQA, reject pants outright for resembling Western male fashion and failing loose-over-garment requirements; more lenient Hanafi or Maliki views allow wide, non-form-fitting trousers under an abaya or jilbab if they obscure shape entirely, though tight or jeans-style variants remain forbidden.[122][123] Eastern religions like Hinduism, Sikhism, and Buddhism impose no scriptural bans on trousers, prioritizing general modesty over garment specifics. Sikh men and women traditionally wear churidar (fitted trousers) with kurtas as part of practical, egalitarian attire instituted by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699, without gender-based restrictions. Buddhist texts emphasize ethical conduct over dress, allowing pants in monastic robes or laywear if non-provocative, as seen in Theravada and Mahayana communities. Hindu practices vary by region and caste but lack prohibitions, with trousers common in urban reformist or diaspora contexts alongside dhoti or salwar.[124]Broader Symbolism and Influences