Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Daylight

View on Wikipedia

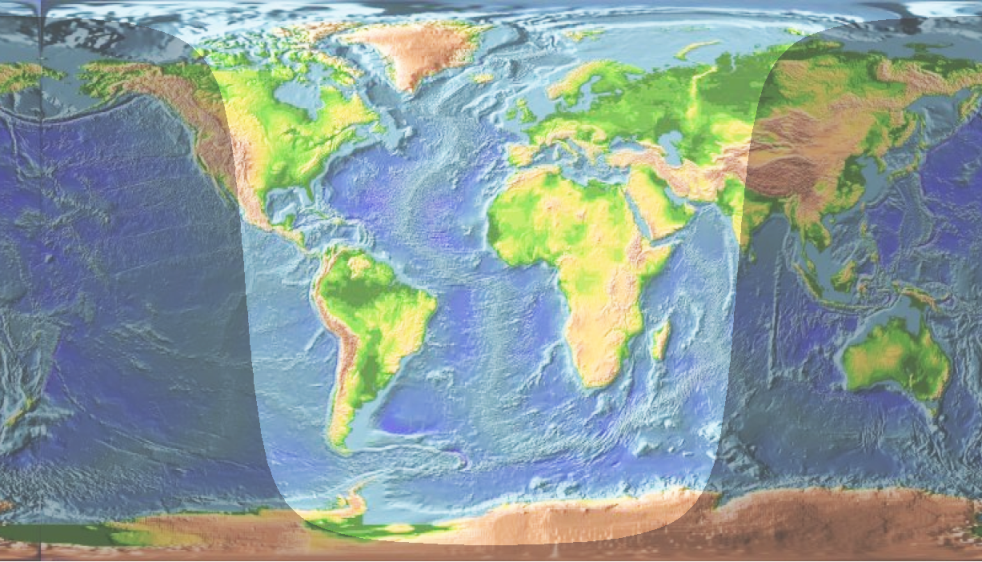

Daylight is the combination of all direct and indirect sunlight during the daytime. This includes direct sunlight, diffuse sky radiation, and (often) both of these reflected by Earth and terrestrial objects, like landforms and buildings. Sunlight scattered or reflected by astronomical objects is generally not considered daylight. Therefore, daylight excludes moonlight, despite it being reflected indirect sunlight.

Definition

[edit]Daylight is present at a particular location, to some degree, whenever the Sun is above the local horizon. This is true for slightly more than 50% of the Earth at any given time, since the Earth's atmosphere refracts some sunlight even when the Sun is below the horizon.

Outdoor illuminance varies from 120,000 lux for direct sunlight at noon, which may cause eye pain, to less than 5 lux for thick storm clouds with the Sun at the horizon (even <1 lux for the most extreme case), which may make shadows from distant street lights visible. It may be darker under unusual circumstances like a solar eclipse or very high levels of atmospheric particulates, which include smoke (see New England's Dark Day), dust,[1] and volcanic ash.[2]

Intensity in different conditions

[edit]| Illuminance | Example |

|---|---|

| 120,000 lux | Brightest sunlight |

| 111,000 lux | Bright sunlight |

| 109,880 lux | AM 1.5 global solar spectrum sunlight (= 1,000.4 W/m2)[3][circular reference] |

| 20,000 lux | Shade illuminated by entire clear blue sky, midday |

| 1,000–2,000 lux | Typical overcast day, midday |

| 400 lux | Sunrise or sunset on a clear day (ambient illumination) |

| <200 lux | Extreme of thickest storm clouds, midday |

| 40 lux | Fully overcast, sunset/sunrise |

| <1 lux | Extreme of thickest storm clouds, sunset/rise |

For comparison, nighttime illuminance levels are:

| Illuminance | Example |

|---|---|

| <1 lux | Moonlight,[4] clear night sky |

| 0.25 lux | A full Moon, clear night sky[5][6] |

| 0.01 lux | A quarter Moon, clear night sky |

| 0.002 lux | Starlight, clear moonless night sky, including airglow[5] |

| 0.0002 lux | Starlight, clear moonless night sky, excluding airglow[5] |

| 0.00014 lux | Venus at brightest,[5] clear night sky |

| 0.0001 lux | Starlight, overcast moonless night sky[5] |

For a table of approximate daylight intensity in the Solar System, see sunlight.

See also

[edit]- Artificial sky

- Color temperature

- Daylight harvesting

- Daylight saving time

- Daylighting

- Daytime – Period of a day in which a location experiences natural illumination

- Moonlight

- Right to light

- Twilight

References

[edit]- ^ Cox, Clifford. "Dust Bowl". Perryton.com. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- ^ "Volcanic Ash Impacts & Mitigation". USGS. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- ^ "Air mass (solar energy)". Wikipedia. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Bunning, Erwin; Moser, Ilse (April 1969). "Interference of moonlight with the photoperiodic measurement of time by plants, and their adaptive reaction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 62 (4): 1018–22. Bibcode:1969PNAS...62.1018B. doi:10.1073/pnas.62.4.1018. PMC 223607. PMID 16591742.

- ^ a b c d e Schlyter, Paul (2006). "Radiometry and photometry in astronomy FAQ".

- ^ "Petzl reference system for lighting performance". Archived from the original on 2008-06-20. Retrieved 2007-04-24.