Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

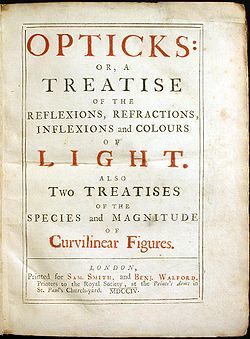

Opticks

View on Wikipedia

Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light is a collection of three books by Isaac Newton that was published in English in 1704 (a scholarly Latin translation appeared in 1706).[1] The treatise analyzes the fundamental nature of light by means of the refraction of light with prisms and lenses, the diffraction of light by closely spaced sheets of glass, and the behaviour of color mixtures with spectral lights or pigment powders. Opticks was Newton's second major work on physical science and it is considered one of the three major works on optics during the Scientific Revolution (alongside Johannes Kepler's Astronomiae Pars Optica and Christiaan Huygens' Treatise on Light).

Key Information

Overview

[edit]The publication of Opticks represented a major contribution to science, different from but in some ways rivalling the Principia, yet Isaac Newton's name did not appear on the cover page of the first edition. Opticks is largely a record of experiments and the deductions made from them, covering a wide range of topics in what was later to be known as physical optics.[1] That is, this work is not a geometric discussion of catoptrics or dioptrics, the traditional subjects of reflection of light by mirrors of different shapes and the exploration of how light is "bent" as it passes from one medium, such as air, into another, such as water or glass. Rather, the Opticks is a study of the nature of light and colour and the various phenomena of diffraction, which Newton called the "inflexion" of light.

Newton sets forth in full his experiments, first reported to the Royal Society of London in 1672,[2] on dispersion, or the separation of light into a spectrum of its component colours. He demonstrates how the appearance of color arises from selective absorption, reflection, or transmission of the various component parts of the incident light.

The major significance of Newton's work is that it overturned the dogma, attributed to Aristotle or Theophrastus and accepted by scholars in Newton's time, that "pure" light (such as the light attributed to the Sun) is fundamentally white or colourless, and is altered into color by mixture with darkness caused by interactions with matter. Newton showed the opposite was true: light is composed of different spectral hues (he describes seven – red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet), and all colours, including white, are formed by various mixtures of these hues. He demonstrates that color arises from a physical property of light – each hue is refracted at a characteristic angle by a prism or lens – but he clearly states that color is a sensation within the mind and not an inherent property of material objects or of light itself. For example, he demonstrates that a red violet (magenta) color can be mixed by overlapping the red and violet ends of two spectra, although this color does not appear in the spectrum and therefore is not a "color of light". By connecting the red and violet ends of the spectrum, he organised all colours as a color circle that both quantitatively predicts color mixtures and qualitatively describes the perceived similarity among hues.

Newton's contribution to prismatic dispersion was the first to outline multiple-prism arrays. Multiple-prism configurations, as beam expanders, became central to the design of the tunable laser more than 275 years later and set the stage for the development of the multiple-prism dispersion theory.[3][4]

Comparison to the Principia

[edit]

Opticks differs in many respects from the Principia. It was first published in English rather than in the Latin[5] used by European philosophers, contributing to the development of a vernacular science literature. The books were a model of popular science exposition: although Newton's English is somewhat dated—he shows a fondness for lengthy sentences with much embedded qualifications—the book can still be easily understood by a modern reader. In contrast, few readers of Newton's time found the Principia accessible or even comprehensible. His formal but flexible style shows colloquialisms and metaphorical word choice.[citation needed]

Unlike the Principia, Opticks is not developed using the geometric convention of propositions proved by deduction from either previous propositions, lemmas or first principles (or axioms). Instead, axioms define the meaning of technical terms or fundamental properties of matter and light, and the stated propositions are demonstrated by means of specific, carefully described experiments. The first sentence of Book I declares "My Design in this Book is not to explain the Properties of Light by Hypotheses, but to propose and prove them by Reason and Experiments. In an Experimentum crucis or "critical experiment" (Book I, Part II, Theorem ii), Newton showed that the color of light corresponded to its "degree of refrangibility" (angle of refraction), and that this angle cannot be changed by additional reflection or refraction or by passing the light through a coloured filter.[6]

The work is a vade mecum of the experimenter's art, displaying in many examples how to use observation to propose factual generalisations about the physical world and then exclude competing explanations by specific experimental tests. Unlike the Principia, which vowed Non fingo hypotheses or "I make no hypotheses" outside the deductive method, the Opticks develops conjectures about light that go beyond the experimental evidence: for example, that the physical behaviour of light was due its "corpuscular" nature as small particles, or that perceived colours were harmonically proportioned like the tones of a diatonic musical scale.

Queries

[edit]

Newton originally considered to write four books, but he dropped the last book on action at a distance.[7] Instead he concluded Opticks a set of unanswered questions and positive assertions referred as queries in Book III. The first set of queries were brief, but the later ones became short essays, filling many pages. In the first edition, these were sixteen such queries;[7][8] that number was increased to 23 in the Latin edition, published in 1706,[7] and then in the revised English edition, published in 1717/18. In the fourth edition of 1730, there were 31 queries.

These queries, especially the later ones, deal with a wide range of physical phenomena that go beyond the topic of optics. The queries concern the nature and transmission of heat; the possible cause of gravity; electrical phenomena; the nature of chemical action; the way in which God created matter; the proper way to do science; and even the ethical conduct of human beings.[8] These queries are not really questions in the ordinary sense. These queries are almost all posed in the negative, as rhetorical questions.[8] That is, Newton does not ask whether light "is" or "may be" a "body." Rather, he declares: "Is not Light a Body?" Stephen Hales, a firm Newtonian of the early eighteenth century, declared that this was Newton's way of explaining "by Quaere."[8]

The first query reads: "Do not Bodies act upon Light at a distance, and by their action bend its Rays; and is not this action (caeteris paribus) strongest at the least distance?" suspecting on the effect of gravity on the trajectory of light rays.[9] This query predates the prediction of gravitational lensing by Albert Einstein's general relativity by two centuries and later confirmed by Eddington experiment in 1919.[9] The first part of query 30 reads "Are not gross Bodies and Light convertible into one another" thereby anticipating mass-energy equivalence.[10] Query 6 of the book reads "Do not black Bodies conceive heat more easily from Light than those of other Colours do, by reason that the Light falling on them is not reflected outwards, but enters into the Bodies, and is often reflected and refracted within them, until it be stifled and lost?", thereby introducing the concept of a black body.[11][12]

The last query (number 31) wonders if a corpuscular theory could explain how different substances react more to certain substances than to others, in particular how aqua fortis (nitric acid) reacts more with calamine that with iron. This 31st query has been often been linked to the origin of the concept of affinity in chemical reactions. Various 18th century historians and chemists like William Cullen and Torbern Bergman, credited Newton for the development affinity tables.[13][a]

Reception

[edit]The Opticks was widely read and debated in England and on the Continent. The early presentation of the work to the Royal Society stimulated a bitter dispute between Newton and Robert Hooke over the "corpuscular" or particle theory of light, which prompted Newton to postpone publication of the work until after Hooke's death in 1703. On the Continent, and in France in particular, both the Principia and the Opticks were initially rejected by many natural philosophers, who continued to defend Cartesian natural philosophy and the Aristotelian version of color, and claimed to find Newton's prism experiments difficult to replicate. Indeed, the Aristotelian theory of the fundamental nature of white light was defended into the 19th century, for example by the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his 1810 Theory of Colours (German: Zur Farbenlehre).

Newtonian science became a central issue in the assault waged by the philosophes in the Age of Enlightenment against a natural philosophy based on the authority of ancient Greek or Roman naturalists or on deductive reasoning from first principles (the method advocated by French philosopher René Descartes), rather than on the application of mathematical reasoning to experience or experiment. Voltaire popularised Newtonian science, including the content of both the Principia and the Opticks, in his Elements de la philosophie de Newton (1738), and after about 1750 the combination of the experimental methods exemplified by the Opticks and the mathematical methods exemplified by the Principia were established as a unified and comprehensive model of Newtonian science. Some of the primary adepts in this new philosophy were such prominent figures as Benjamin Franklin, Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, and James Black.

Subsequent to Newton, much has been amended. Thomas Young and Augustin-Jean Fresnel showed that the wave theory Christiaan Huygens described in his Treatise on Light (1690) could prove that colour is the visible manifestation of light's wavelength. Science also slowly came to recognize the difference between perception of colour and mathematisable optics. The German poet Goethe, with his epic diatribe Theory of Colours, could not shake the Newtonian foundation – but "one hole Goethe did find in Newton's armour.. Newton had committed himself to the doctrine that refraction without colour was impossible. He therefore thought that the object-glasses of telescopes must for ever remain imperfect, achromatism and refraction being incompatible. This inference was proved by Dollond to be wrong." (John Tyndall, 1880[14])

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Étienne François Geoffroy is credited for the first affinity table in 1718, but his relation to Newton or knowledge of the 31st query is unclear.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Newton, Isaac (1998). Opticks: or, a treatise of the reflexions, refractions, inflexions and colours of light. Also two treatises of the species and magnitude of curvilinear figures. Commentary by Nicholas Humez (Octavo ed.). Palo Alto, Calif.: Octavo. ISBN 1-891788-04-3. (Opticks was originally published in 1704).

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "Hydrostatics, Optics, Sound and Heat". Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ F. J. Duarte and J. A. Piper, Dispersion theory of multiple-prism beam expanders for pulsed dye lasers, Opt. Commun. 43, 303–307 (1982).

- ^ P. Rowlands, Newton and Modern Physics (World Scientific, London, 2017).

- ^ Newton, Isaac; Shapiro, Alan E. (2021). The optical papers of Isaac Newton. Cambridge New York: Cambridge university press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-521-30218-0.

- ^ Thompson, Evan (2 September 2003). Colour Vision. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-134-90080-0.

- ^ a b c James, Peter J. (1985). "Stephen Hales' "Statical Way"". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 7 (2): 287–299. JSTOR 23328812. PMID 3909194.

- ^ a b c d Buchwald, Jed Z.; Cohen, I. Bernard (2001). Isaac Newton's Natural Philosophy. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-52425-4.

- ^ a b Schneider, P.; Ehlers, J.; Falco, E. E. (29 June 2013). Gravitational Lenses. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-662-03758-4.

- ^ Simmons, George Finlay (2022). Differential Equations with Applications and Historical Notes (3rd ed.). CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-4987-0259-1.

- ^ Bochner, Salomon (1981). Role of Mathematics in the Rise of Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Pr. pp. 221, 347. ISBN 978-0-691-08028-4.

- ^ Rowlands, Peter (2017). Newton - Innovation And Controversy. World Scientific Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 9781786344045.

- ^ a b Newman, William R. (11 December 2018). Newton the Alchemist: Science, Enigma, and the Quest for Nature's "Secret Fire". Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17487-7.

- ^ Popular Science Monthly/Volume 17/July 1880)http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_17/July_1880/Goethe's_Farbenlehre:_Theory_of_Colors_II

External links

[edit]Full and free online editions of Newton's Opticks

- Rarebookroom, First edition

- ETH-Bibliothek, First edition

- Gallica, First edition

- Internet Archive, Fourth edition

- Project Gutenberg digitized text & images of the Fourth Edition

- Cambridge University Digital Library, Papers on Hydrostatics, Optics, Sound and Heat – Manuscript papers by Isaac Newton containing draft of Opticks

Opticks public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Opticks public domain audiobook at LibriVox