Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Delta-sigma modulation

View on Wikipedia

| Passband modulation |

|---|

|

| Analog modulation |

| Digital modulation |

| Hierarchical modulation |

| Spread spectrum |

| See also |

Delta-sigma (ΔΣ; or sigma-delta, ΣΔ) modulation is an oversampling method for encoding signals into low bit depth digital signals at a very high sample-frequency as part of the process of delta-sigma analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) and digital-to-analog converters (DACs). Delta-sigma modulation achieves high quality by utilizing a negative feedback loop during quantization to the lower bit depth that continuously corrects quantization errors and moves quantization noise to higher frequencies well above the original signal's bandwidth. Subsequent low-pass filtering for demodulation easily removes this high frequency noise and time averages to achieve high accuracy in amplitude, which can be ultimately encoded as pulse-code modulation (PCM).

Both ADCs and DACs can employ delta-sigma modulation. A delta-sigma ADC (e.g. Figure 1 top) encodes an analog signal using high-frequency delta-sigma modulation and then applies a digital filter to demodulate it to a high-bit digital output at a lower sampling-frequency. A delta-sigma DAC (e.g. Figure 1 bottom) encodes a high-resolution digital input signal into a lower-resolution but higher sample-frequency signal that may then be mapped to voltages and smoothed with an analog filter for demodulation. In both cases, the temporary use of a low bit depth signal at a higher sampling frequency simplifies circuit design and takes advantage of the efficiency and high accuracy in time of digital electronics.

Primarily because of its cost efficiency and reduced circuit complexity, this technique has found increasing use in modern electronic components such as DACs, ADCs, frequency synthesizers, switched-mode power supplies and motor controllers.[1] The coarsely-quantized output of a delta-sigma ADC is occasionally used directly in signal processing or as a representation for signal storage (e.g., Super Audio CD stores the raw output of a 1-bit delta-sigma modulator).

While this article focuses on synchronous modulation, which requires a precise clock for quantization, asynchronous delta-sigma modulation instead runs without a clock.

Motivation

[edit]When transmitting an analog signal directly, all noise in the system and transmission is added to the analog signal, reducing its quality. Digitizing it enables noise-free transmission, storage, and processing. There are many methods of digitization.

In Nyquist-rate ADCs, an analog signal is sampled at a relatively low sampling frequency just above its Nyquist rate (twice the signal's highest frequency) and quantized by a multi-level quantizer to produce a multi-bit digital signal. Such higher-bit methods seek accuracy in amplitude directly, but require extremely precise components and so may suffer from poor linearity.

Advantages of oversampling

[edit]Oversampling converters instead produce a lower bit depth result at a much higher sampling frequency. This can achieve comparable quality by taking advantage of:

- Higher accuracy in time (afforded by high-speed digital circuits and highly accurate clocks).

- Higher linearity afforded by low-bit ADCs and DACs (for instance, a 1-bit DAC that only outputs two values of a precise high voltage and a precise low voltage is perfectly linear, in principle).

- Noise shaping: moving noise to higher frequencies above the signal of interest, so they can be easily removed with low-pass filtering.

- Reduced steepness requirement for the analog low-pass anti-aliasing filters. High-order filters with a flat passband cost more to make in the analog domain than in the digital domain.

Frequency/resolution tradeoff

[edit]Another key aspect given by oversampling is the frequency/resolution tradeoff. The decimation filter put after the modulator not only filters the whole sampled signal in the band of interest (cutting the noise at higher frequencies), but also reduces the sampling rate, and hence the representable frequency range, of the signal, while increasing the sample amplitude resolution. This improvement in amplitude resolution is obtained by a sort of averaging of the higher-data-rate bitstream.

Improvement over delta modulation

[edit]Delta modulation is an earlier related low-bit oversampling method that also uses negative feedback, but only encodes the derivative of the signal (its delta) rather than its amplitude. The result is a stream of marks and spaces representing up or down of the signal's movement, which must be integrated to reconstruct the signal's amplitude. Delta modulation has several drawbacks. The differentiation alters the signal's spectrum by amplifying high-frequency noise, attenuating low-frequencies,[2] and dropping the DC component. This makes its dynamic range and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) inversely proportional to signal frequency. Delta modulation suffers from slope overload if signals move too fast. And it is susceptible to transmission disturbances that result in cumulative error.

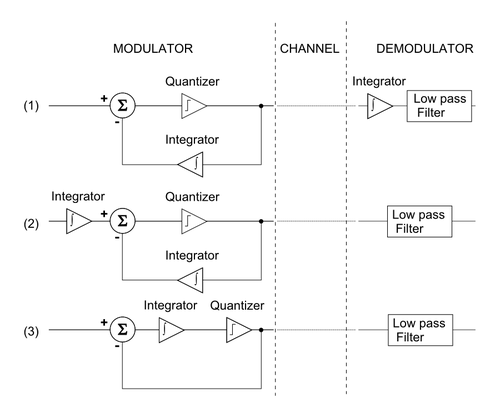

Delta-sigma modulation rearranges the integrator and quantizer of a delta modulator so that the output carries information corresponding to the amplitude of the input signal instead of just its derivative.[3] This also has the benefit of incorporating desirable noise shaping into the conversion process, to deliberately move quantization noise to frequencies higher than the signal. Since the accumulated error signal is lowpass filtered by the delta-sigma modulator's integrator before being quantized, the subsequent negative feedback of its quantized result effectively subtracts the low-frequency components of the quantization noise while leaving the higher frequency components of the noise.

1-bit delta-sigma modulation is pulse-density modulation

[edit]In the specific case of a single-bit synchronous ΔΣ ADC, an analog voltage signal is effectively converted into a pulse frequency, or pulse density, which can be understood as pulse-density modulation (PDM). A sequence of positive and negative pulses, representing bits at a known fixed rate, is very easy to generate, transmit, and accurately regenerate at the receiver, given only that the timing and sign of the pulses can be recovered. Given such a sequence of pulses from a delta-sigma modulator, the original waveform can be reconstructed with adequate precision.

The use of PDM as a signal representation is an alternative to PCM. Alternatively, the high-frequency PDM can later be downsampled through decimation and requantized to convert it into a multi-bit PCM code at a lower sampling frequency closer to the Nyquist rate of the frequency band of interest.

History and variations

[edit]The seminal[4] paper combining feedback with oversampling to achieve delta modulation was by F. de Jager of Philips Research Laboratories in 1952.[5]

The principle of improving the resolution of a coarse quantizer by use of feedback, which is the basic principle of delta-sigma conversion, was first described in a 1954-filed patent by C. Chapin Cutler of Bell Labs.[6] It was not named as such until a 1962 paper[7] by Inose et al. of University of Tokyo, which came up with the idea of adding a filter in the forward path of the delta modulator.[8][note 1] However, Charles B Brahm of United Aircraft Corp[9] in 1961 filed a patent "Feedback integrating system"[10] with a feedback loop containing an integrator with multi-bit quantization shown in its Fig 1.[2]

Wooley's "The Evolution of Oversampling Analog-to-Digital Converters"[4] gives more history and references to relevant patents. Some avenues of variation (which may be applied in different combinations) are the modulator's order, the quantizer's bit depth, the manner of decimation, and the oversampling ratio.

Higher-order modulator

[edit]

Noise of the quantizer can be further shaped by replacing the quantizer itself with another ΔΣ modulator. This creates a 2nd-order modulator, which can be rearranged in a cascaded fashion (Figure 2).[2] This process can be repeated to increase the order even more.

While 1st-order modulators are unconditionally stable, stability analysis must be performed for higher-order noise-feedback modulators. Alternatively, noise-feedforward configurations are always stable and have simpler analysis.[11]§6.1

Multi-bit quantizer

[edit]The modulator can also be classified by the bit depth of its quantizer. A quantizer that distinguishes between N-levels is called a log2N bit quantizer. For example, a simple comparator has 2 levels and so is 1 bit quantizer; a 3-level quantizer is called a 1.5 bit quantizer; a 4-level quantizer is a 2-bit quantizer; a 5-level quantizer is called a 2.5-bit quantizer.[12] Higher bit quantizers inherently produce less quantization noise.

One criticism of 1-bit quantization is that adequate amounts of dither cannot be used in the feedback loop, so distortion can be heard under some conditions (more discussion at Direct Stream Digital § DSD vs. PCM).[13][14]

Subsequent decimation

[edit]Decimation is strongly associated with delta-sigma modulation, but is distinct and outside the scope of this article. The original 1962 paper didn't describe decimation. Oversampled data in the early days was sent as is. The proposal to decimate oversampled delta-sigma data using digital filtering before converting it into PCM audio was made by D. J. Goodman at Bell Labs in 1969,[15] to reduce the ΔΣ signal from its high sampling rate while increasing its bit depth. Decimation may be done in a separate chip on the receiving end of the delta-sigma bit stream, sometimes by a dedicated module inside of a microcontroller,[16] which is useful for interfacing with PDM MEMS microphones,[17] though many ΔΣ ADC integrated circuits include decimation. Some microcontrollers even incorporate both the modulator and decimator.[18]

Decimation filters most commonly used for ΔΣ ADCs, in order of increasing complexity and quality, are:

- Boxcar moving average filter (simple moving average or sinc-in-frequency or sinc1 filter): This is the easiest digital filter and retains a sharp step response, but is mediocre at separating frequency bands[19] and suffers from intermodulation distortion. The filter can be implemented by simply counting how many samples during a larger sampling interval are high. The 1974 paper from another Bell Labs researcher, J. C. Candy, "A Use of Limit Cycle Oscillations to Obtain Robust Analog-to-Digital Converters"[20] was one of the early examples of this.

- Cascaded integrator–comb filters: These are called sincN filters, equivalent to cascading the above sinc1 filter N times and rearranging the order of operations for computational efficiency. Lower N filters are simpler, settle faster, and have less attenuation in the baseband, while higher N filters are slightly more complex and settle slower and have more droop in the passband, but better attenuate undesired high frequency noise. Compensation filters can however be applied to counteract undesired passband attenuation.[21] SincN filters are appropriate for decimating sigma delta modulation down to four times the Nyquist rate.[22] The height of the first sideload is -13·N dB and the height of successive lobes fall off gradually, but only the areas around the nulls will alias into the low frequency band of interest; for instance when downsampling by 8, the largest aliased high frequency component may be -16 dB below the peak of the band of interest with a sinc1 filter but -40 dB below for a sinc3 filter, and if only interested in a narrower bandwidth, even fewer high frequency components will alias into it (see Figures 7–9 of Lyons article).[23]

- Windowed sinc-in-time (brick-wall in frequency) filters: Although the sinc function's infinite support prevents it from being realizable in finite time, the sinc function can instead be windowed to realize finite impulse response filters. This approximated filter design, while maintaining almost no attenuation of the lower-frequency band of interest, still removes almost all undesired high-frequency noise. The downside is poor performance in the time domain (e.g. step response overshoot and ripple), higher delay (i.e. their convolution time is inversely proportional to their cutoff transition steepness), and higher computational requirements.[24] They are the de facto standard for high fidelity digital audio converters.

Other loop filters

[edit]Most commercial ΔΣ modulators use integrators as the loop filter, because as low-pass filters they push quantization noise up in frequency, which is useful for baseband signals. But a ΔΣ modulator's filter does not necessarily need to be a low-pass filter. If a band-pass filter is used instead, then quantization noise is moved up and down in frequency away from the filter's pass-band, so a subsequent pass-band decimation filter will result in a ΔΣ ADC with a bandpass characteristic.[25]

Reduction of baseband noise by increasing oversampling ratio and ΔΣM order

[edit]

When a signal is quantized, the resulting signal can be approximated by addition of white noise with approximately equal intensity across the entire spectrum. In reality, the quantization noise is, of course, not independent of the signal and this dependence results in limit cycles and is the source of idle tones and pattern noise in delta-sigma converters. However, adding dithering noise (Figure 3) reduces such distortion by making quantization noise more random.

ΔΣ ADCs reduce the amount of this noise in the baseband by spreading it out and shaping it so it is mostly in higher frequencies. It can then be easily filtered out with inexpensive digital filters, without high-precision analog circuits needed by Nyquist ADCs.

Oversampling to spread out quantization noise

[edit]Quantization noise in the baseband frequency range (from DC to ) may be reduced by increasing the oversampling ratio (OSR) defined by

where is the sampling frequency and is the Nyquist rate (the minimum sampling rate needed to avoid aliasing, which is twice the original signal's maximum frequency ). Since oversampling is typically done in powers of two, represents how many times OSR is doubled.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the total amount of quantization noise is the same both in a Nyquist converter (yellow + green areas) and in an oversampling converter (blue + green areas). But oversampling converters distribute that noise over a much wider frequency range. The benefit is that the total amount of noise in the frequency band of interest is dramatically smaller for oversampling converters (just the small green area), than for a Nyquist converter (yellow + green total area).

Noise shaping

[edit]Figure 4 shows how ΔΣ modulation shapes noise to further reduce the amount of quantization noise in the baseband in exchange for increasing noise at higher frequencies (where it can be easily filtered out). The curves of higher-order ΔΣ modulators achieve even greater reduction of noise in the baseband.

These curves are derived using mathematical tools called the Laplace transform (for continuous-time signals, e.g. in an ADC's modulation loop) or the Z-transform (for discrete-time signals, e.g. in a DAC's modulation loop). These transforms are useful for converting harder math from the time domain into simpler math in the complex frequency domain of the complex variable (in the Laplace domain) or (in the z-domain).

Analysis of ΔΣ ADC modulation loop in Laplace domain

[edit]Figure 5 represents the 1st-order ΔΣ ADC modulation loop (from Figure 1) as a continuous-time linear time-invariant system in the Laplace domain with the equation:

The Laplace transform of integration of a function of time corresponds to simply multiplication by in Laplace notation. The integrator is assumed to be an ideal integrator to keep the math simple, but a real integrator (or similar filter) may have a more complicated expression.

The process of quantization is approximated as addition with a quantization error noise source. The noise is often assumed to be white and independent of the signal, though as quantization (signal processing) § Additive noise model explains that is not always a valid assumption (particularly for low-bit quantization).

Since the system and Laplace transform are linear, the total behavior of this system can be analyzed by separating how it affects the input from how it affects the noise:[11]§6

Low-pass filter on input

[edit]To understand how the system affect the input signal only, the noise is temporarily imagined to be 0:

which can be rearranged to yield the following transfer function:

This transfer function has a single pole at in the complex plane, so it effectively acts as a 1st-order low-pass filter on the input signal. (Note: its cutoff frequency could be adjusted as desired by including multiplication by a constant in the loop).

High-pass filter on noise

[edit]To understand how the system affects the noise only, the input instead is temporarily imagined to be 0:

which can be rearranged to yield the following transfer function:

This transfer function has a single zero at and a single pole at so the system effectively acts as a high-pass filter on the noise that starts at 0 at DC, then gradually rises until it reaches the cutoff frequency, and then levels off.

Analysis of synchronous ΔΣ modulation loop in z-domain

[edit]The synchronous ΔΣ DAC's modulation loop (Figure 6) meanwhile is in discrete-time and so its analysis is in the z-domain. It is very similar to the above analysis in Laplace domain and produces similar curves. Note: many sources[11]§6.1[26][27] also analyze a ΔΣ ADC's modulation loop in the z-domain, which implicitly treats the continuous analog input as a discrete-time signal. This may be a valid approximation provided that the input signal is already bandlimited and can be assumed to be not changing on time scales higher than the sampling rate. It is particularly appropriate when the modulator is implemented as a switched capacitor circuit, which work by transferring charge between capacitors in clocked time steps.

Integration in discrete-time can be an accumulator which repeatedly sums its input with the previous result of its summation This is represented in the z-domain by feeding back a summing node's output though a 1-clock cycle delay stage (notated as ) into another input of the summing node, yielding . Its transfer function is often used to label integrators in block diagrams.

In a ΔΣ DAC, the quantizer may be called a requantizer or a digital-to-digital converter (DDC), because its input is already digital and quantized but is simply reducing from a higher bit depth to a lower bit depth digital signal. This is represented in the z-domain by another delay stage in series with adding quantization noise. (Note: some sources may have swapped ordering of the and additive noise stages.)

The modulator's z-domain equation arranged like Figure 6 is:which can be rearranged to express the output in terms of the input and noise:The input simply comes out of the system delayed by one clock cycle. The noise term's multiplication by represents a first difference backward filter (which has a single pole at the origin and a single zero at ) and thus high-pass filters the noise.

Higher order modulators

[edit]Without getting into the mathematical details,[26](equations 8-11) cascading integrators to create an -order modulator results in:Since this first difference backwards filter is now raised to the power it will have a steeper noise shaping curve, for improved properties of greater attenuation in the baseband, so a dramatically larger portion of the noise is above the baseband and can be easily filtered by an ideal low-pass filter.

Theoretical effective number of bits

[edit]The theoretical SNR in decibels (dB) for a sinusoid input travelling through a -order modulator with a OSR (and followed by an ideal low-pass decimation filter) can be mathematically derived to be approximately:[26](equations 12-21)

The theoretical effective number of bits (ENOB) resolution is thus improved by bits when doubling the OSR (incrementing ), and by bits when incrementing the order. For comparison, oversampling a Nyquist ADC (without any noise shaping) only improves its ENOB by bits for every doubling of the OSR,[28] which is only 1⁄3 of the ENOB growth rate of a 1st-order ΔΣM.

| Oversampling ratio | each OSR

doubling | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 OSR | 25 OSR | 26 OSR | 27 OSR | 28 OSR | ||

1st-order:

|

24 dB

3+3⁄4 bits |

33 dB

5+1⁄4 bits |

42 dB

6+3⁄4 bits |

51 dB

8+1⁄4 bits |

60 dB

9+3⁄4 bits |

+1+1⁄2 bits |

2nd-order:

|

39 dB

6+1⁄4 bits |

54 dB

8+3⁄4 bits |

69 dB

11+1⁄4 bits |

84 dB

13+3⁄4 bits |

99 dB

16+1⁄4 bits |

+2+1⁄2 bits |

3rd-order:

|

53 dB

8+3⁄4 bits |

75 dB

12+1⁄4 bits |

96 dB

15+3⁄4 bits |

117 dB

19+1⁄4 bits |

138 dB

22+3⁄4 bits |

+3+1⁄2 bits |

4th-order:

|

68 dB

11+1⁄4 bits |

95 dB

15+3⁄4 bits |

112 dB

20+1⁄4 bits |

149 dB

24+3⁄4 bits |

177 dB

29+1⁄2 bits |

+4+1⁄2 bits |

5th-order:

|

83 dB

13+1⁄2 bits |

116 dB

19 bits |

149 dB

24+1⁄2 bits |

182 dB

30 bits |

215 dB

35+1⁄2 bits |

+5+1⁄2 bits |

6th-order:

|

99 dB

16 bits |

137 dB

22+1⁄2 bits |

176 dB

29 bits |

215 dB

35+1⁄2 bits |

254 dB

42 bits |

+6+1⁄2 bits |

each additional order:

|

+2+1⁄2 bits | +3+1⁄2 bits | +4+1⁄2 bits | +5+1⁄2 bits | +6+1⁄2 bits | |

These datapoints are theoretical. In practice, circuits inevitably experience other noise sources that limit resolution, making the higher-resolution cells impractical.

Relationship to delta modulation

[edit]

Delta-sigma modulation is related to delta modulation by the following steps (Figure 7):[11]§6

- Start with a block diagram of a delta modulator/demodulator.

- The linearity property of integration, , makes it possible to move the integrator from the demodulator to be before the summation.

- Again, the linearity property of integration allows the two integrators to be combined and a delta-sigma modulator/demodulator block diagram is obtained.

If quantization were homogeneous (e.g., if it were linear), the above would be a sufficient derivation of their hypothetical equivalence. But because the quantizer is not homogeneous, delta-sigma is inspired by delta modulation, but the two are distinct in operation.

From the first block diagram in Figure 7, the integrator in the feedback path can be removed if the feedback is taken directly from the input of the low-pass filter. Hence, for delta modulation of input signal vin, the low-pass filter sees the signal

However, delta-sigma modulation of the same input signal places at the low-pass filter

In other words, doing delta-sigma modulation instead of delta modulation has effectively swapped the ordering of the integrator and quantizer operations. The net effect is a simpler implementation that has the profound added benefit of shaping the quantization noise to be mostly in frequencies above the signals of interest. This effect becomes more dramatic with increased oversampling, which allows for quantization noise to be somewhat programmable. On the other hand, delta modulation shapes both noise and signal equally.

Additionally, the quantizer (e.g., comparator) used in delta modulation has a small output representing a small step up and down the quantized approximation of the input while the quantizer used in delta-sigma must take values outside of the range of the input signal.

In general, delta-sigma has some advantages versus delta modulation:

- The structure is simplified as

- only one integrator is needed,

- the demodulator can be a simple linear filter (e.g., RC or LC filter) to reconstruct the signal, and

- the quantizer (e.g., comparator) can have full-scale outputs.

- The quantized value is the integral of the difference signal, which

- makes it less sensitive to the rate of change of the signal, and

- helps capture low frequency and DC components.

Analog-to-digital conversion example

[edit]Delta-sigma ADCs vary in complexity. The below circuit focuses on a simple 1st-order, 2-level quantization synchronous delta-sigma ADC without decimation.

Simplified circuit example

[edit]To ease understanding, a simple circuit schematic (Figure 8a) using ideal elements is simulated (Figure 8b voltages). It is functionally the same Analog-to-Digital ΔΣ modulation loop in Figure 1 (note: the 2-input inverting integrator combines the summing junction and integrator and produces a negative feedback result, and the flip-flop combines the sampled quantizer and conveniently naturally functions as a 1-bit DAC too).

The 20 kHz input sine wave s(t) is converted to a 1-bit PDM digital result Q(t). 20 kHz is used as an example because that is considered the upper limit of human hearing.

This circuit can be laid out on a breadboard with inexpensive discrete components (note some variations use different biasing and use simpler RC low-pass filters for integration instead of op amps).[29][30]

For simplicity, the D flip-flop is powered by dual supply voltages of VDD = +1 V and VSS = -1 V, so its binary output Q(t) is either +1 V or -1 V.

2-input inverting integrator

[edit]The 2-input inverting op amp integrator combines s(t) with Q(t) to produce Ɛ(t):The Greek letter epsilon is used because Ɛ(t) contains the accumulated error that is repeatedly corrected by the feedback mechanism. While both its inputs s(t) and Q(t) vary between -1 and 1 volts, Ɛ(t) instead only varies by a couple millivolts about 0 V.

Because of the integrator's negative sign, when Ɛ(t) next gets sampled to produce Q(t), the +Q(t) in this integral actually represents negative feedback from the previous clock cycle.

Quantizer and sampler flip-flop

[edit]An ideal D flip-flop samples Ɛ(t) at the clock rate of 1 MHz. The scope view (Figure 8b) has a minor division equal to the sampling period of 1 μs, so every minor division corresponds to a sampling event. Since the flip-flop is assumed to be ideal, it treats any input voltage greater than 0 V as logical high and any input voltage smaller than 0 V as logical low, no matter how close it is to 0 V (ignoring issues of sample-and-hold time violations and metastability).

Whenever a sampling event occurs:

- if Ɛ(t) is above the 0 V threshold, then Q(t) will go high (+1 V), or

- if Ɛ(t) is below the 0 V threshold, then Q(t) will go low (-1 V).

Q(t) is sent out as the resulting PDM output and also fed back to the 2-input inverting integrator.

Demodulation

[edit]The rightmost integrator performs digital-to-analog conversion on Q(t) to produce a demodulated analog output r(t), which reconstructs the original sine wave input as piece-wise linear diagonal segments. Although r(t) appears coarse at this 50x oversampling rate, r(t) can be low-pass filtered to isolate the original signal. As the sampling rate is increased relative to the input signal's maximum frequency, r(t) will more closely approximate the original input s(t).

Digital-to-analog conversion

[edit]It is worth noting that if no decimation ever took place, the digital representation from a 1-bit delta-sigma modulator is simply a PDM signal, which can easily be converted to analog using a low-pass filter, as simple as a resistor and capacitor.[30]

However, in general, a delta-sigma DAC converts a discrete time series signal of digital samples at a high bit depth into a low-bit-depth (often 1-bit) signal, usually at a much higher sampling rate. That delta-modulated signal can then be accurately converted into analog (since lower bit-depth DACs are easier to be highly-linear), which then goes through inexpensive low-pass filtering in the analog domain to remove the high-frequency quantization noise inherent to the delta-sigma modulation process.

Upsampling

[edit]As the discrete Fourier transform and discrete-time Fourier transform articles explain, a periodically sampled signal inherently contains multiple higher frequency copies or images of the signal. It is often desirable to remove these higher-frequency images prior to performing the actual delta-sigma modulation stage, in order to ease requirements on the eventual analog low-pass filter. This can be done by upsampling using an interpolation filter and is often the first step prior to performing delta-sigma modulation in DACs. Upsampling is strongly associated with delta-sigma DACs but not strictly part of the actual delta-sigma modulation stage (similar to how decimation is strongly associated with delta-sigma ADCs but not strictly part of delta-sigma modulation either), and the details are out of the scope of this article.

Digital-to-digital delta-sigma modulation

[edit]The modulation loop in Figure 6 in § Noise shaping can easily be laid out with basic digital elements of a subtractor for the difference, an accumulator for the integrator, and a lower-bit register for the quantization, which carries over the most-significant bit(s) from the integrator to be the feedback for the next cycle.

Multi-stage noise shaping

[edit]This simple 1st-order modulation can be improved by cascading two or more overflowing accumulators, each of which is equivalent to a 1st-order delta-sigma modulator. The resulting multi-stage noise shaping (MASH)[31] structure has a steeper noise shaping property, so is commonly used in digital audio. The carry outputs are combined through summations and delays to produce a binary output, the width of which depends on the number of stages (order) of the MASH. Besides its noise-shaping function, it has two more attractive properties:

- simple to implement in hardware; only common digital blocks such as accumulators, adders, and D flip-flops are required

- unconditionally stable (there are no feedback loops outside the accumulators)

Naming

[edit]The technique was first presented in the early 1960s by professor Yasuhiko Yasuda while he was a student at the University of Tokyo.[32][11] The name delta-sigma comes directly from the presence of a delta modulator and an integrator, as firstly introduced by Inose et al. in their patent[clarification needed] application.[7] That is, the name comes from integrating or summing differences, which, in mathematics, are operations usually associated with Greek letters sigma and delta respectively.

In the 1970s, Bell Labs engineers used the terms sigma-delta because the precedent was to name variations on delta modulation with adjectives preceding delta, and an Analog Devices magazine editor justified in 1990 that the functional hierarchy is sigma-delta, because it computes the integral of a difference.[33]

Both names sigma-delta and delta-sigma are frequently used.

Asynchronous delta-sigma modulation

[edit]

Kikkert and Miller published a continuous-time variant called Asynchronous Delta Sigma Modulation (ADSM or ASDM) in 1975 which uses either a Schmitt trigger (i.e. a comparator with hysteresis) or (as the paper argues is equivalent) a comparator with fixed delay.[34]

In the example in Figure 9, when the integral of the error exceeds its limits, the output changes state, producing a pulse-width modulated (PWM) output wave.

Amplitude information is converted, without quantization noise, into time information of the output PWM.[35] To convert this continuous time PWM to discrete time, the PWM may be sampled by a time-to-digital converter, whose limited resolution adds noise which can be shaped by feeding it back.[36]

See also

[edit]- Pulse-width modulation

- Continuously variable slope delta modulation

- Class-D amplifier (sometimes[12] use delta-sigma modulation)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The delta-sigma configuration as described by Inose et al. in 1962 was devised to solve problems in the accurate transmission of analog signals. In that application it was the pulse stream that was transmitted and the original analog signal recovered with a lowpass filter after the received pulses had been reformed. This low pass filter performed the summation function associated with Σ. The highly mathematical treatment of transmission errors was introduced by them and is appropriate when applied to the pulse stream but these errors are lost in the accumulation process associated with Σ.

References

[edit]- ^ Sangil Park, Principles of Sigma-Delta Modulation for Analog-to-Digital Converters (PDF), Motorola, retrieved 2017-09-01

- ^ a b c Razavi, Behzad (2016-06-21). "A Circuit for all Seasons: The Delta-Sigma Modulator" (PDF). IEEE Solid-State Circuits Magazine. 8 (2): 10–15. doi:10.1109/MSSC.2016.2543061. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-09. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ Inose, H.; Yasuda, Y. (1963-11-01). "A unity bit coding method by negative feedback". Proceedings of the IEEE. 51 (11): 1524–1535. doi:10.1109/PROC.1963.2622. ISSN 1558-2256.

- ^ a b Wooley, Bruce A. (2012-03-22). "The Evolution of Oversampling Analog-to-Digital Converters" (PDF). IEEE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-06-28. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ F. de Jager, "Delta modulation, a method of PCM transmission using the 1-unit code," Philips Res. Rep., vol. 7, pp. 442–466, 1952.

- ^ US patent 2967962, Cutler, Cassius C., "Transmission systems employing quantization", issued March 8, 1960

- ^ a b Inose, H.; Yasuda, Y.; Murakami, J. (1962-05-06). "A Telemetering System by Code Modulation - Δ- ΣModulation". IRE Transactions on Space Electronics and Telemetry. SET-8 (3) (published 1962-09-01): 204–209. doi:10.1109/IRET-SET.1962.5008839. ISSN 2331-1657. S2CID 51647729.

- ^ "Continuous-time sigma-delta modulation". Continuous-Time Sigma-Delta Modulation for A/D Conversion in Radio Receivers: Chapter 4: Continuous-time sigma-delta modulation. The International Series in Engineering and Computer Science. Vol. 634. Springer Publishing. 2001. pp. 29–71. doi:10.1007/0-306-48004-2_3. ISBN 9780306480041. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ "Charles Brahm Obituary (1926 - 2021) - Hartford, CT - Hartford Courant". Legacy.com. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ US3192371A, Brahm, Charles B., "Feedback integrating system", issued 1965-06-29

- ^ a b c d e Sangil Park, Principles of sigma-delta modulation for analog-to-digital converters (PDF), Motorola, archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-06-21

- ^ a b Sigma-delta class-D amplifier and control method for a sigma-delta class-D amplifier by Jwin-Yen Guo and Teng-Hung Chang

- ^ Lipschitz, Stanley P.; Vanderkooy, John (2000-09-22). "Why Professional 1-Bit Sigma-Delta Conversion is a Bad Idea" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-11-02.

- ^ Lipshitz, Stanley P.; Vanderkooy, John (2001-05-12). "Why 1-Bit Sigma-Delta Conversion is Unsuitable for High-Quality Applications" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-30. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ^ "Data Converter Architectures: Chapter 3" (PDF). Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^ "AN4990: Getting started with sigma-delta digital interface on applicable STM32 microcontrollers" (PDF). STMicroelectronics. March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ Kite, Thomas (2012). "Understanding PDM Digital Audio" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- ^ "MSP430i2xx Family" (PDF). Texas Instruments. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-15. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ Smith, Steven W. (1999). "Chapter 15: Moving Average Filters" (PDF). The Scientist and Engineer's Guide to Digital Signal Processing (2nd ed.). San Diego, Calif: California Technical Pub. ISBN 978-0-9660176-4-9.

- ^ Candy, J. (1974). "A Use of Limit Cycle Oscillations to Obtain Robust Analog-to-Digital Converters". IEEE Transactions on Communications. 22 (3): 298–305. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1974.1092194. ISSN 1558-0857.

- ^ "AN-455: Understanding CIC Compensation Filters" (PDF). Altera. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-05. Retrieved 2024-01-03.

- ^ Candy, J.C. (1986). "Decimation for Sigma Delta Modulation". IEEE Transactions on Communications. 34: 72–76. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1986.1096432.

- ^ Lyons, Rick (2020-03-26). "A Beginner's Guide To Cascaded Integrator-Comb (CIC) Filters". dsprelated.com. Archived from the original on 2023-10-22. Retrieved 2024-01-03.

- ^ Smith, Steven W. (1999). "Chapter 16: Windowed-Sinc Filters" (PDF). The Scientist & Engineer's Guide to Digital Signal Processing (2nd ed.). San Diego, Calif: California Technical Pub. ISBN 978-0-9660176-4-9.

- ^ Bryant, James M. "ADCs for DSP Applications" (PDF). Analog Devices. p. 3.18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-07-26.

- ^ a b c Van Ess, Dave. "Signals From Noise: Calculating Delta-Sigma SNRs" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-06. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ^ Reiss, Joshua D. (2008). "UNDERSTANDING SIGMA–DELTA MODULATION: The Solved and Unsolved Issues" (PDF). J. Audio Eng. Soc., Vol. 56, No. 1/2, 2008 January/February. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-09-01. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ^ Brown, Ryan; Singh, Sameer (2016). "Application Report: General Oversampling of MSP ADCs for Higher Resolution" (PDF). Texas Instruments. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-01. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ^ "Activity: Delta - Sigma Modulator [Analog Devices Wiki]". Analog Devices. 2021-01-09. Archived from the original on 2023-04-01. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- ^ a b Ellsworth, Jeri (2012-11-05). "One Bit ADC - Short Circuits". YouTube. Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- ^ "15-25 MHZ Fractional-N Synthesizer".

- ^ "発見と発明のデジタル博物館卓越研究データベース・電気・情報通信関連・研究情報(登録番号671)". Archived from the original on 2022-04-08.

- ^ Sheingold, Dan (1990). "Editor's Notes: Σ-∆ or ∆-Σ?" (PDF). Analog Devices. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Kikkert, C. J.; Miller, D. J. (1975-04-01). "Asynchronous Delta Sigma Modulation". Proceedings of the IREE Australia. 36 (4): 83–88.

- ^ Stork, Milan (2015). "Asynchronous sigma-delta modulator and fast demodulator". 2015 25th International Conference Radioelektronika (RADIOELEKTRONIKA). pp. 180–183. doi:10.1109/RADIOELEK.2015.7129003. ISBN 978-1-4799-8117-5.

- ^ Wei, Chen (2014). "Asynchronous Sigma Delta Modulators for Data Conversion - Ph.D. Thesis" (PDF). Imperial College of London. p. 88. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

Further reading

[edit]- Walt Kester (October 2008). "ADC Architectures III: Sigma-Delta ADC Basics" (PDF). Analog Devices. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- R. Jacob Baker (2009). CMOS Mixed-Signal Circuit Design (2nd ed.). Wiley-IEEE. ISBN 978-0-470-29026-2.

- R. Schreier; G. Temes (2005). Understanding Delta-Sigma Data Converters. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-46585-0.

- S. Norsworthy; R. Schreier; G. Temes (1997). Delta-Sigma Data Converters. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-7803-1045-2.

- J. Candy; G. Temes (1992). Oversampling Delta-sigma Data Converters. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-87942-285-1.

- Chen, Wei (2013). Asynchronous sigma delta modulators for data conversion (PDF) (PhD thesis). Imperial College London. doi:10.25560/23651. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

External links

[edit]- 1-bit A/D and D/A Converters Archived 2021-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Sigma-delta techniques extend DAC resolution article by Tim Wescott 2004-06-23

- Tutorial on Designing Delta-Sigma Modulators: Part I and Part II by Mingliang (Michael) Liu

- Gabor Temes' Publications

- Sigma-Delta Modulation Primer Part II Contains Block diagrams, code, and simple explanations

- Example Simulink model & scripts for continuous-time sigma-delta ADC Contains example matlab code and Simulink model

- Bruce Wooley's Delta-Sigma Converter Projects

- An Introduction to Delta Sigma Converters (which covers both ADCs and DACs sigma-delta)

- Demystifying Sigma-Delta ADCs. This in-depth article covers the theory behind a Delta-Sigma analog-to-digital converter.

- One-Bit Delta Sigma D/A Conversion Part I: Theory article by Randy Yates presented at the 2004 comp.dsp conference

- MASH (Multi-stAge noise SHaping) structure with both theory and a block-level implementation of a MASH

- Continuous time sigma-delta ADC noise shaping filter circuit architectures discusses architectural trade-offs for continuous-time sigma-delta noise-shaping filters

- Delta Sigma Converters: Modulation – intuitive motivation for why a delta-sigma modulator works

- Digital accelerometer with feedback control using sigma-delta modulation

- Analog Devices Sigma-Delta ADC tutorial (interactive)

![{\displaystyle [{\text{in}}({\text{s}})-\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}({\text{s}})]\cdot {\frac {1}{\text{s}}}+{\text{noise}}({\text{s}})=\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}({\text{s}})\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9b9d083b4beb5197f302afdd3c097978e21f69c3)

![{\displaystyle [{\text{in}}({\text{s}})-\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}_{\text{in}}({\text{s}})]\cdot {\frac {1}{\text{s}}}+0=\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}_{\text{in}}({\text{s}})\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5a8a3f0da21116ae108305caffc662a419507043)

![{\displaystyle [0-\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}_{\text{noise}}({\text{s}})]\cdot {\frac {1}{\text{s}}}+{\text{noise}}({\text{s}})=\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}_{\text{noise}}({\text{s}})\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fab09aca140acee35f265ed5aad3d0747d4cc8c9)

![{\displaystyle x[n]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/864cbbefbdcb55af4d9390911de1bf70167c4a3d)

![{\displaystyle y[n]=x[n]+y[n-1].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/55affaa374d6e3008554b05d99462c1ceca20121)

![{\displaystyle [{\text{in}}({\text{z}})-\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}({\text{z}})]\cdot {\frac {1}{1-{\text{z}}^{\text{-1}}}}\cdot {\text{z}}^{\text{-1}}+{\text{noise}}({\text{z}})=\Delta \Sigma {\text{M}}({\text{z}})\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/07279ce729a4b3aebd704f68517e470ea68094c6)