Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Adder (electronics)

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on | |||||||

| Arithmetic logic circuits | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quick navigation | |||||||

|

Components

|

|||||||

|

See also |

|||||||

An adder, or summer,[1] is a digital circuit that performs addition of numbers. In many computers and other kinds of processors, adders are used in the arithmetic logic units (ALUs). They are also used in other parts of the processor, where they are used to calculate addresses, table indices, increment and decrement operators and similar operations.

Although adders can be constructed for many number representations, such as binary-coded decimal or excess-3, the most common adders operate on binary numbers. In cases where two's complement or ones' complement is being used to represent negative numbers, it is trivial to modify an adder into an adder–subtractor. Other signed number representations require more logic around the basic adder.

History

[edit]George Stibitz invented the 2-bit binary adder (the Model K) in 1937.

Binary adders

[edit]Half adder

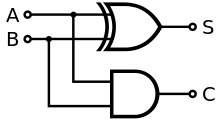

[edit]The half adder adds two single binary digits and . It has two outputs, sum () and carry (). The carry signal represents an overflow into the next digit of a multi-digit addition. The value of the sum is . The simplest half-adder design, pictured on the right, incorporates an XOR gate for and an AND gate for . The Boolean logic for the sum (in this case ) will be whereas for the carry () will be . With the addition of an OR gate to combine their carry outputs, two half adders can be combined to make a full adder.[2]

The truth table for the half adder is:

Inputs Outputs A B Cout S 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0

Various half adder digital logic circuits:

-

Half adder in action.

-

Schematic of half adder implemented with five NAND gates.

-

Schematic symbol for a 1-bit half adder.

Full adder

[edit]A full adder adds binary numbers and accounts for values carried in as well as out. A one-bit full-adder adds three one-bit numbers, often written as , , and ; and are the operands, and is a bit carried in from the previous less-significant stage.[3] The circuit produces a two-bit output. Output carry and sum are typically represented by the signals and , where the sum equals . The full adder is usually a component in a cascade of adders, which add 8, 16, 32, etc. bit binary numbers.

A full adder can be implemented in many different ways such as with a custom transistor-level circuit or composed of other gates. The most common implementation is with:

The above expressions for and can be derived from using a Karnaugh map to simplify the truth table.

In this implementation, the final OR gate before the carry-out output may be replaced by an XOR gate without altering the resulting logic. This is because when A and B are both 1, the term is always 0, and hence can only be 0. Thus, the inputs to the final OR gate can never be both 1 (this is the only combination for which the OR and XOR outputs differ).

Due to the functional completeness property of the NAND and NOR gates, a full adder can also be implemented using nine NAND gates,[4] or nine NOR gates.

Using only two types of gates is convenient if the circuit is being implemented using simple integrated circuit chips which contain only one gate type per chip.

A full adder can also be constructed from two half adders by connecting and to the input of one half adder, then taking its sum-output as one of the inputs to the second half adder and as its other input, and finally the carry outputs from the two half-adders are connected to an OR gate. The sum-output from the second half adder is the final sum output () of the full adder and the output from the OR gate is the final carry output (). The critical path of a full adder runs through both XOR gates and ends at the sum bit . Assumed that an XOR gate takes 1 delays to complete, the delay imposed by the critical path of a full adder is equal to:

The critical path of a carry runs through one XOR gate in adder and through 2 gates (AND and OR) in carry-block and therefore, if AND or OR gates take 1 delay to complete, has a delay of:

The truth table for the full adder is:

Inputs Outputs A B Cin Cout S 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1

Inverting all inputs of a full adder also inverts all of its outputs, which can be used in the design of fast ripple-carry adders, because there is no need to invert the carry.[5]

Various full adder digital logic circuits:

-

Full adder in action.

-

Schematic of full adder implemented with nine NAND gates.

-

Schematic of full adder implemented with nine NOR gates.

-

Schematic symbol for a 1-bit full adder with Cin and Cout drawn on sides of block to emphasize their use in a multi-bit adder

Adders supporting multiple bits

[edit]Ripple-carry adder

[edit]

It is possible to create a logical circuit using multiple full adders to add N-bit numbers. Each full adder inputs a , which is the of the previous adder. This kind of adder is called a ripple-carry adder (RCA), since each carry bit "ripples" to the next full adder. The first (and only the first) full adder may be replaced by a half adder (under the assumption that ).

The layout of a ripple-carry adder is simple, which allows fast design time; however, the ripple-carry adder is relatively slow, since each full adder must wait for the carry bit to be calculated from the previous full adder. The gate delay can easily be calculated by inspection of the full adder circuit. Each full adder requires three levels of logic. In a 32-bit ripple-carry adder, there are 32 full adders, so the critical path (worst case) delay is 3 (from input to of first adder) + 31 × 2 (for carry propagation in latter adders) = 65 gate delays.[6] The general equation for the worst-case delay for a n-bit carry-ripple adder, accounting for both the sum and carry bits, is:

A design with alternating carry polarities and optimized AND-OR-Invert gates can be about twice as fast.[7][5]

Carry-lookahead adder (Weinberger and Smith, 1958)

[edit]

To reduce the computation time, Weinberger and Smith invented a faster way to add two binary numbers by using carry-lookahead adders (CLA).[8] They introduced two signals ( and ) for each bit position, based on whether a carry is propagated through from a less significant bit position (at least one input is a 1), generated in that bit position (both inputs are 1), or killed in that bit position (both inputs are 0). In most cases, is simply the sum output of a half adder and is the carry output of the same adder. After and are generated, the carries for every bit position are created.

Mere derivation of Weinberger-Smith CLA recurrence, are: Brent–Kung adder (BKA),[9] and the Kogge–Stone adder (KSA).[10][11] This was shown in Oklobdzija and Zeydel paper in IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits.[12]

Some other multi-bit adder architectures break the adder into blocks. It is possible to vary the length of these blocks based on the propagation delay of the circuits to optimize computation time. These block based adders include the carry-skip (or carry-bypass) adder which will determine and values for each block rather than each bit, and the carry-select adder which pre-generates the sum and carry values for either possible carry input (0 or 1) to the block, using multiplexers to select the appropriate result when the carry bit is known.

By combining multiple carry-lookahead adders, even larger adders can be created. This can be used at multiple levels to make even larger adders. For example, the following adder is a 64-bit adder that uses four 16-bit CLAs with two levels of lookahead carry units.

Other adder designs include the carry-select adder, conditional sum adder, carry-skip adder, and carry-complete adder.

Carry-save adders

[edit]If an adding circuit is to compute the sum of three or more numbers, it can be advantageous to not propagate the carry result. Instead, three-input adders are used, generating two results: a sum and a carry. The sum and the carry may be fed into two inputs of the subsequent 3-number adder without having to wait for propagation of a carry signal. After all stages of addition, however, a conventional adder (such as the ripple-carry or the lookahead) must be used to combine the final sum and carry results.

3:2 compressors

[edit]A full adder can be viewed as a 3:2 lossy compressor: it sums three one-bit inputs and returns the result as a single two-bit number; that is, it maps 8 input values to 4 output values. (the term "compressor" instead of "counter" was introduced in[13])Thus, for example, a binary input of 101 results in an output of 1 + 0 + 1 = 10 (decimal number 2). The carry-out represents bit one of the result, while the sum represents bit zero. Likewise, a half adder can be used as a 2:2 lossy compressor, compressing four possible inputs into three possible outputs.

Such compressors can be used to speed up the summation of three or more addends. If the number of addends is exactly three, the layout is known as the carry-save adder. If the number of addends is four or more, more than one layer of compressors is necessary, and there are various possible designs for the circuit: the most common are Dadda and Wallace trees. This kind of circuit is most notably used in multiplier circuits, which is why these circuits are also known as Dadda and Wallace multipliers.

Quantum adders

[edit]

Using only the Toffoli and CNOT quantum logic gates, it is possible to produce quantum full- and half-adders.[14][15][16] The same circuits can also be implemented in classical reversible computation, as both CNOT and Toffoli are also classical logic gates.

Since the quantum Fourier transform has a low circuit complexity, it can efficiently be used for adding numbers as well.[17][18][19]

Analog adders

[edit]Just as in Binary adders, combining two input currents effectively adds those currents together. Within the constraints of the hardware, non-binary signals (i.e. with a base higher than 2) can be added together to calculate a sum. Also known as a "summing amplifier",[20] this technique can be used to reduce the number of transistors in an addition circuit.

See also

[edit]- Binary multiplier

- Subtractor

- Electronic mixer — for adding analog signals

References

[edit]- ^ Singh, Ajay Kumar (2010). "10. Adder and Multiplier Circuits". Digital VLSI Design. Prentice Hall India. pp. 321–344. ISBN 978-81-203-4187-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lancaster, Geoffrey A. (2004). "10. The Software Developer's View of the Hardware §Half Adders, §Full Adders". Excel HSC Software Design and Development. Pascal Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-74125175-3.

- ^ Mano, M. Morris (1979). Digital Logic and Computer Design. Prentice-Hall. pp. 119–123. ISBN 978-0-13-214510-7. OCLC 1413827071.

- ^ Teja, Ravi (2021-04-15), Half Adder and Full Adder Circuits, retrieved 2021-07-27

- ^ a b c Fischer, P. "Einfache Schaltungsblöcke" (PDF). Universität Heidelberg. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-05. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ Satpathy, Pinaki (2016). "3. Design of Multi-Bit Full Adder using different logic §3.1 4-bit full Adder". Design and Implementation of Carry Select Adder Using T-Spice. Anchor Academic Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-3-96067058-2.

- ^ Burgess, Neil (2011). Fast Ripple-Carry Adders in Standard-Cell CMOS VLSI. 20th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic. pp. 103–111. doi:10.1109/ARITH.2011.23. ISBN 978-1-4244-9457-6.

- ^ Weinberger, A.; Smith, J.L. (1958). "A Logic for High-Speed Addition" (PDF). Nat. Bur. Stand. Circ. (591). National Bureau of Standards: 3–12.

- ^ Brent, Richard Peirce; Kung, Hsiang Te (March 1982). "A Regular Layout for Parallel Adders". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-31 (3): 260–264. doi:10.1109/TC.1982.1675982. ISSN 0018-9340. S2CID 17348212. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017.

- ^ Kogge, Peter Michael; Stone, Harold S. (August 1973). "A Parallel Algorithm for the Efficient Solution of a General Class of Recurrence Equations". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-22 (8): 786–793. doi:10.1109/TC.1973.5009159. S2CID 206619926.

- ^ Reynders, Nele; Dehaene, Wim (2015). Ultra-Low-Voltage Design of Energy-Efficient Digital Circuits. Analog Circuits and Signal Processing. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16136-5. ISBN 978-3-319-16135-8. ISSN 1872-082X. LCCN 2015935431.

- ^ Zeydel, B.R.; Baran, D.; Oklobdzija, V.G. (June 2010). "Energy Efficient Design of High-Performance VLSI Adders" (PDF). IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 45 (6): 1220–33. doi:10.1109/JSSC.2010.2048730.

- ^ Oklobdzija, V.G.; Villeger, D. (June 1995). "Improving multiplier design by using improved column compression tree and optimized final adder in CMOS technology" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems. 3 (2): 292–301. doi:10.1109/92.386228.

- ^ Feynman, Richard P. (1986). "Quantum mechanical computers". Foundations of Physics. 16 (6). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 507–531. Bibcode:1986FoPh...16..507F. doi:10.1007/bf01886518. ISSN 0015-9018. S2CID 122076550.

- ^ "Code example: Quantum full adder". QuTech (Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) and the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO)).

- ^ Dibyendu Chatterjee, Arijit Roy (2015). "A transmon-based quantum half-adder scheme". Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics. 2015 (9): 093A02. Bibcode:2015PTEP.2015i3A02C. doi:10.1093/ptep/ptv122.

- ^ Draper, Thomas G. (7 Aug 2000). "Addition on a Quantum Computer". arXiv:quant-ph/0008033.

- ^ Ruiz-Perez, Lidia; Juan Carlos, Garcia-Escartin (2 May 2017). "Quantum arithmetic with the quantum Fourier transform". Quantum Information Processing. 16 (6): 152. arXiv:1411.5949v2. Bibcode:2017QuIP...16..152R. doi:10.1007/s11128-017-1603-1. S2CID 10948948.

- ^ Şahin, Engin (2020). "Quantum arithmetic operations based on quantum Fourier transform on signed integers". International Journal of Quantum Information. 18 (6): 2050035. arXiv:2005.00443v3. Bibcode:2020IJQI...1850035S. doi:10.1142/s0219749920500355. ISSN 1793-6918.

- ^ "Summing Amplifier is an Op-amp Voltage Adder". 22 August 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Liu, Tso-Kai; Hohulin, Keith R.; Shiau, Lih-Er; Muroga, Saburo (January 1974). "Optimal One-Bit Full-Adders with Different Types of Gates". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-23 (1). Bell Laboratories: IEEE: 63–70. doi:10.1109/T-C.1974.223778. ISSN 0018-9340. S2CID 7746693.

- Lai, Hung Chi; Muroga, Saburo (September 1979). "Minimum Binary Parallel Adders with NOR (NAND) Gates". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-28 (9). IEEE: 648–659. doi:10.1109/TC.1979.1675433. S2CID 23026844.

- Mead, Carver; Conway, Lynn (1980) [December 1979]. Introduction to VLSI Systems. Addison-Wesley. Bibcode:1980aw...book.....M. ISBN 978-0-20104358-7. OCLC 634332043. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- Davio, Marc; Dechamps, Jean-Pierre; Thayse, André (1983). Digital Systems, with algorithm implementation. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-10413-1. LCCN 82-2710. OCLC 8282197.

- Gosling, John (January 1971). "Review of High-Speed Addition Techniques". Proc. IEE. 188 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1049/piee.1971.0004.

External links

[edit] Media related to Adders (digital circuits) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Adders (digital circuits) at Wikimedia Commons- 8-bit Full Adder and Subtractor, a demonstration of an interactive Full Adder built in JavaScript solely for learning purposes.

- Brunnock, Sean. "Interactive demonstrations of half and full adders in HTML5".

- Shirriff, Ken (November 2020). "Reverse-engineering the carry-lookahead circuit in the Intel 8008 processor".

Adder (electronics)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

An adder in electronics is a combinational digital circuit that computes the arithmetic sum of two binary numbers, generating a sum bit and a carry bit as outputs.[4] This circuit operates without memory elements, relying solely on the current inputs to produce outputs instantaneously.[5] The fundamental purpose of an adder is to enable binary arithmetic addition in core components of digital systems, such as central processing units (CPUs), arithmetic logic units (ALUs), and memory addressing mechanisms.[6] Unlike subtractors, which compute differences, or multipliers, which perform repeated additions for products, adders specifically handle the summation of binary operands to support essential computational tasks.[7] Binary addition is governed by straightforward rules analogous to decimal addition but using base-2 digits: 0 + 0 = 0 (no carry), 0 + 1 = 1 (no carry), 1 + 0 = 1 (no carry), and 1 + 1 = 0 with a carry of 1 to the next bit position.[8] These rules ensure that each bit position's sum accounts for potential carries from lower positions, forming the basis for multi-bit operations.[9] In a basic adder without carry-in, the sum bit is computed as , where and are the input bits and represents the exclusive-OR (XOR) operation.[10] For a general single-bit adder incorporating carry propagation, the circuit accepts inputs , , and carry-in (), producing outputs sum () and carry-out (); this structure is depicted in a block diagram as follows: A ───┐

├─► [Adder] ───► S

B ───┤

Cin ───┘ Cout ───►

A ───┐

├─► [Adder] ───► S

B ───┤

Cin ───┘ Cout ───►

Applications in Digital Systems

Adders serve as fundamental building blocks in digital systems, particularly as core components within Arithmetic Logic Units (ALUs) that execute essential operations such as addition and subtraction on binary data.[12] In central processing units (CPUs), adders facilitate address generation by computing memory locations and effective addresses during instruction execution, enabling efficient data fetching and program flow control. Floating-point units (FPUs) rely on specialized adders to handle the alignment, addition, and normalization stages required for floating-point arithmetic, supporting high-precision computations in scientific and graphical applications.[13] Additionally, in digital signal processing (DSP) systems, adders contribute to filter implementations and transform calculations, where their efficiency directly influences real-time performance.[14] Beyond basic arithmetic, adders integrate into more complex structures like multipliers and counters. Array multipliers, for instance, employ arrays of full adders to sum partial products generated from AND gates, enabling parallel binary multiplication essential for applications in cryptography and image processing.[15] Counters utilize adder circuits to increment binary values sequentially or in parallel, forming the basis for timing, sequencing, and frequency division in embedded systems and synchronous designs.[16] The design of adders profoundly impacts overall system performance, often acting as critical path bottlenecks that limit processor clock speeds due to carry propagation delays.[17] Engineers must balance trade-offs in power, performance, and area (PPA) metrics, where faster adder topologies like carry-lookahead variants reduce latency at the expense of increased silicon area and power consumption, influencing the scalability of high-frequency microprocessors. In modern processors, such as those based on Intel x86 architectures, 64-bit adders are optimized for integer execution units to handle wide data paths, achieving multi-gigahertz operation through advanced prefix computations.[18] Similarly, ARM-based systems incorporate 32- and 64-bit adders in their execution pipelines, supporting energy-efficient computing in mobile and server environments.[19] Emerging applications extend adders into specialized domains, including AI accelerators where they form the accumulation stage in multiply-accumulate (MAC) units for neural network training and inference, processing vast matrix operations with minimal latency.[20] In error-correcting codes, adders enable syndrome calculations and error polynomial evaluations within decoders like those for Reed-Solomon or BCH codes, enhancing data reliability in storage and communication systems.[21] These integrations underscore adders' versatility in driving advancements in machine learning hardware and fault-tolerant computing.Historical Development

Early Concepts in Computing

The precursors to electronic adders emerged in the realm of mechanical computing devices during the early 19th century, driven by the need to automate complex mathematical tabulations. Charles Babbage conceived the Difference Engine in 1822 as a mechanical calculator designed to compute polynomial functions using the method of finite differences, which relies fundamentally on repeated additions. The machine employed a series of brass gears and levers to perform these additions: rotating gears represented numerical values, and levers facilitated the carry mechanism by engaging or disengaging gear teeth to propagate sums between digit positions. Although only a portion was built before the project was abandoned in 1833 due to funding issues, this design laid the groundwork for automated arithmetic by mechanizing addition without human intervention.[22] Babbage further advanced these concepts with the Analytical Engine, outlined in 1837, which aimed to be a general-purpose programmable computer capable of performing arbitrary calculations, including addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Its arithmetic unit, known as the "mill," utilized intricate gear assemblies to handle multi-digit operations in a decimal system; for addition, gears on figure wheels incremented values through direct meshing, with a separate carry mechanism using sliding levers to transfer overflows between columns. This gear-based approach allowed for sequential processing of numbers stored on rotating shafts, marking a significant step toward modular arithmetic hardware, though the full machine was never constructed due to technical and financial challenges.[23] The transition to electromechanical adders occurred in the late 1930s with the advent of relay-based computing. Konrad Zuse developed the Z1 in 1938 as a programmable binary computer, initially using mechanical components like thin metal strips for logic, but he quickly recognized the limitations and incorporated electromagnetic relays in subsequent designs such as the Z2 (1939) and Z3 (1941) to implement reliable adders. In these machines, a relay adder circuit used four relays per bit position to compute the sum and carry of two binary digits: relays acted as switches to detect inputs, perform XOR and AND operations for sum and carry, and propagate results through chained logic, enabling floating-point arithmetic with addition times of approximately 0.3 seconds. This electromechanical approach improved reliability over pure mechanics by leveraging electrical signaling for faster switching, though noise and wear remained issues.[24] The vacuum tube era brought fully electronic adders with the completion of ENIAC in 1945, the first general-purpose electronic digital computer, which performed arithmetic using over 17,000 vacuum tubes organized into 20 accumulators for parallel addition and subtraction. Each accumulator featured a set of decade ring counters—circular arrays of 10 vacuum tubes per digit, where a "1" propagated sequentially around the ring to represent decimal values from 0 to 9—coupled with tube-based adder circuits that detected carries via threshold voltages and flipped states to increment the next digit. These ring counters and adders enabled high-speed decimal arithmetic, processing up to 5,000 additions per second, a vast improvement over mechanical systems. ENIAC's design addressed the computational bottlenecks of its time, particularly the labor-intensive preparation of firing tables.[25] This evolution from mechanical to electronic adders was propelled by the urgent demands of World War II, especially the U.S. Army's need for rapid generation of artillery ballistics tables, which traditionally required months of manual calculations by human "computers" to account for variables like trajectory, wind, and gravity. Pre-war mechanical calculators could not meet the scale—over 30 tables per weapon system—so the Army Ordnance Department sponsored projects like ENIAC to accelerate these computations from weeks to hours, enabling more accurate and timely battlefield decisions. This wartime imperative not only funded the shift to vacuum tube technology but also highlighted the strategic value of automated addition in scientific and military applications.[26]Key Milestones in Electronic Adders

The transition to transistor-based electronic adders in the 1950s represented a pivotal advancement in digital arithmetic, replacing power-hungry vacuum tubes with more reliable and compact solid-state devices. IBM's 608 Transistor Calculator, introduced in 1954, was the company's first product employing transistor circuits for computational tasks, including basic addition operations using discrete point-contact transistors arranged in logic gates. This design achieved significant reductions in size, power consumption, and heat generation compared to prior tube-based calculators, laying the groundwork for transistorized computing systems.[27] A major breakthrough in multi-bit addition efficiency came in 1958 with the invention of the carry-lookahead adder by Arnold Weinberger and John L. Smith at IBM. Their approach, detailed in the paper "A Logic for High-Speed Addition," generated carry signals in parallel rather than sequentially, drastically reducing propagation delay in n-bit adders from O(n) to O(log n) in the best case. This innovation enabled faster arithmetic units in early transistor computers like the IBM 7090, introduced in 1959 as one of the first commercial fully transistorized general-purpose machines, and influenced subsequent designs in high-performance computing.[28][29] The 1960s ushered in the integrated circuit era, transforming adder implementations from discrete components to monolithic chips. Fairchild Semiconductor's Micrologic family, launched in 1961, comprised the first commercially available silicon integrated circuits using resistor-transistor logic (RTL), including basic gates that facilitated the construction of compact full adders on a single chip. By the mid-1960s, these ICs were integral to systems like the Apollo Guidance Computer, where space-constrained adders performed reliable binary arithmetic.[30] In the 1980s and 1990s, very-large-scale integration (VLSI) techniques drove further optimizations in microprocessor adders, balancing speed, area, and power for widespread commercial adoption. The Intel 8086 microprocessor (1978), a cornerstone of the x86 architecture, employed an optimized 16-bit carry-skip adder incorporating a Manchester carry chain and custom carry propagation logic to achieve efficient addition within its ALU, supporting the burgeoning personal computing market. Concurrently, carry-select adders gained prominence in VLSI designs for their ability to precompute sums assuming different carry inputs, reducing worst-case delays; a notable early implementation appeared in patent literature around 1986, influencing high-speed ALUs in processors like the Intel 80386.[31][32] From the 2000s onward, relentless CMOS scaling enabled adders to handle wider bit widths while emphasizing power efficiency amid rising transistor densities. Advances in process nodes, such as 90 nm and below, incorporated techniques like dynamic voltage scaling and low-power logic styles to mitigate leakage in adder circuits used in mobile and server processors. In recent years (2020–2025), the focus has shifted toward approximate adders for error-tolerant applications like machine learning, where minor inaccuracies can yield substantial energy savings without compromising overall accuracy. For instance, designs integrating approximate full adders into deep neural network accelerators have demonstrated up to 50% power reductions in convolution operations, as explored in hardware approximations for DNNs.[33]Fundamental Binary Adders

Half-Adder

A half-adder is a basic combinational logic circuit in digital electronics that performs binary addition of two single-bit inputs, denoted as A and B, to produce two outputs: a sum bit S and a carry-out bit C.[34] This circuit represents the simplest form of an adder, handling the addition without considering any incoming carry from a previous stage.[35] The logical expressions for the outputs are derived from the binary addition rules. The sum bit S is the exclusive-OR (XOR) of the inputs, indicating whether the inputs differ (resulting in 1) or are the same (resulting in 0): The carry-out bit C is the logical AND of the inputs, generated only when both A and B are 1: [36][37] These expressions can be implemented using a minimal set of gates: one XOR gate for the sum and one AND gate for the carry-out. The circuit diagram consists of the two inputs connected to both gates, with the XOR output as S and the AND output as C.[37] The behavior of the half-adder is fully described by its truth table, which enumerates all possible input combinations and corresponding outputs:| A | B | S | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Full-Adder

A full adder is a combinational digital circuit that adds three single-bit binary inputs—A, B, and carry-in (C_in)—to produce a sum output (S) and a carry-out (C_out). This design extends the basic addition capability beyond two bits by incorporating the carry from a previous addition stage, making it the building block for multi-bit arithmetic units in processors and other digital systems.[40] The logical behavior of the full adder is defined by the following Boolean equations: These equations represent the sum as the parity of the three inputs and the carry-out as the majority function among them. The truth table enumerates all eight input combinations and their corresponding outputs, verifying the equations:| A | B | C_in | S | C_out |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Multi-Bit Binary Adders

Ripple-Carry Adder

The ripple-carry adder is constructed by chaining n full-adders in series, with the carry-out signal from each full-adder connected to the carry-in input of the subsequent full-adder, beginning from the least significant bit position.[44] This serial arrangement allows the adder to compute the sum of two n-bit binary numbers by processing bits sequentially from low to high significance.[45] During operation, the carry signal generated at each bit position "ripples" through the chain to influence higher bits, propagating from the least significant bit to the most significant bit until the final carry-out is produced.[46] This sequential propagation ensures correct arithmetic summation but introduces timing dependencies between stages.[47] The primary performance limitation of the ripple-carry adder is its delay, which scales linearly as O(n gate delays due to carry propagation across all n bits; for instance, the worst-case path requires approximately 2n XOR gate delays, as each full-adder contributes two levels of logic for carry generation and propagation.[46] In practice, this results in significant latency for larger word sizes, where the critical path traverses the entire chain.[45] Key advantages of the ripple-carry adder include its straightforward design, which requires minimal additional logic beyond the full-adders, and a low transistor count, such as 28 transistors per bit in a standard CMOS implementation.[48] These attributes make it efficient in terms of area and power for small-scale applications.[44] However, the extended critical path delay renders the ripple-carry adder impractical for wide adders exceeding 16 bits, as the propagation time becomes a bottleneck in high-speed digital systems.[46] As an illustrative example, consider a 4-bit ripple-carry adder computing the sum of A = 1010₂ (decimal 10) and B = 0111₂ (decimal 7) with an initial carry-in of 0. The bit-wise computation proceeds as follows:| Bit Position | A_i | B_i | C_in | Sum_i | C_out |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (LSB) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 (MSB) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Carry-Select Adder

The carry-select adder (CSLA) is a multi-bit binary adder architecture designed to accelerate carry propagation by precomputing possible sum outputs for each block of bits, thereby reducing the overall addition time compared to sequential carry methods. Introduced in 1962, it divides the n-bit operands into smaller blocks, typically of equal size, where the first block uses a conventional ripple-carry adder (RCA) to compute its sum and carry output. For subsequent blocks, two parallel RCAs compute sums assuming an input carry of 0 or 1, and multiplexers select the appropriate results based on the actual carry from the previous block. This parallel precomputation allows the sums to be ready before the controlling carry arrives, with the final delay dominated by the carry selection chain rather than full propagation through all bits.[49] The design operates by partitioning the adder into m blocks of b bits each, where n = m × b. Within each block i (for i > 1), the two RCAs generate sum vectors S_i^0 and S_i^1 along with their respective carries C_{i+1}^0 and C_{i+1}^1. Once the carry C_i from the prior block is available, a set of 2:1 multiplexers selects between S_i^0/S_i^1 and routes the corresponding C_{i+1} to the next block. The first block's RCA computes unconditionally, providing the initial carry for selection. This structure ensures that carry propagation is limited to the mux chain after the initial block's computation.[49] In terms of delay, the CSLA achieves an asymptotic complexity of O(√n) for n-bit addition when block sizes are optimized. The worst-case delay is the sum of the carry generation time in the first b-bit RCA plus the selection time across the remaining (m-1) blocks. Assuming a 2-gate delay per full adder stage in the RCA and a 2-gate delay per multiplexer, the first block's carry delay is approximately 2b gates, and the mux chain adds 2(m-1) gates, yielding a total of 2(b + m - 1). To minimize this, b is chosen near √n, resulting in O(√n) overall. For medium-width adders (e.g., 16-64 bits), this provides significantly faster performance than the O(n) ripple-carry adder. Hardware implementation involves duplicating RCA structures for each non-first block, plus the multiplexer array for sum and carry selection. For a 16-bit CSLA with four 4-bit blocks, the first block requires one 4-bit RCA (4 full adders), while the next three blocks each need two 4-bit RCAs (8 full adders each) and 2:1 muxes for each of the 4 sum bits plus carry muxes, totaling 28 full adders versus 16 for a pure 16-bit RCA—a 1.75× increase due to redundancy. Modern implementations often use optimized RCA blocks like Brent-Kung prefixes within sections to further reduce internal delays.[49] The power and area trade-offs of the CSLA stem from this redundancy: it consumes more silicon area and dynamic power than a ripple-carry adder due to the duplicated logic and parallel computations, with estimates showing about 1.5-2× the gate count and power for equivalent bit widths. However, static power is comparable since idle duplicate paths do not significantly contribute, and the reduced critical path lowers overall energy per operation in high-speed applications. These penalties make CSLA suitable for medium n where speed gains outweigh costs, but less ideal for very wide adders.[50] Evolutionarily, the original linear CSLA used uniform block sizes for simplicity, but variable block sizing emerged to optimize delay by increasing block width progressively (e.g., 2-bit, 3-bit, 4-bit blocks in a 16-bit design) to balance RCA and mux delays, potentially reducing total delay by 10-20% over linear versions without excessive area increase. This variable approach, refined in subsequent designs, allows finer tuning for specific technologies.[51] As an example, consider an 8-bit CSLA with two 4-bit blocks. The first block is a single 4-bit RCA computing sum bits [3:0] and carry C4 in 8 gate delays (2 per stage). The second block has two parallel 4-bit RCAs precomputing S[7:4]^0/C5^0 (Cin=0) and S[7:4]^1/C5^1 (Cin=1), each taking 8 gate delays independently. Upon C4 arrival, four 2:1 muxes select the correct S[7:4] and one mux selects C5, adding 2 gate delays. Total worst-case delay: 8 (first RCA) + 2 (mux) = 10 gate delays, versus 16 for an 8-bit RCA— a 37.5% reduction. The block diagram consists of the initial RCA feeding C4 to the second block's mux control, with parallel RCAs feeding sum muxes and carry mux to output.[49]Carry-Skip Adder

The carry-skip adder is a multi-bit binary adder that accelerates carry propagation beyond the limitations of the ripple-carry adder by organizing full-adders into blocks and incorporating bypass logic to skip over blocks when the carry signal can pass through unchanged. This design divides the -bit operands into blocks, where each block consists of a chain of full-adders connected in ripple fashion, augmented with skip circuitry that monitors the block's overall propagate condition. The skip logic, often implemented as a chain of OR gates or a multiplexer, allows the incoming carry to the block to be directly routed to the outgoing carry if the block propagates the carry without modification or generation.[52] The operation relies on the propagate signal for each bit position , defined as , where and are the input bits at that position. For a block spanning bits 0 to , the block propagate signal is computed as If , it indicates that no generate ( for all in the block) occurs and the carry propagates unchanged, enabling the skip: the carry-in to the block () is muxed directly to the carry-out (), bypassing the internal ripple delays. Otherwise, the carry ripples through the block's full-adders as usual, computing intermediate carries sequentially. This conditional bypassing reduces propagation time variably based on operand values, with the internal sums always computed via the full-adder chain regardless of skipping.[52] The delay of a carry-skip adder depends on block configuration and operand patterns. In the worst case for uniform block sizes of bits, the delay is , optimized at to yield . However, using progressively increasing block sizes (e.g., 2, 3, 4, 7 bits in a 16-bit adder) further optimizes the worst-case delay, still achieving O(√n) overall but with better constants than uniform sizing. For 32- to 64-bit widths, the average-case delay outperforms the ripple-carry adder's linear due to frequent skipping in typical data distributions, though the best case approaches constant time per skipped block.[53][52] Optimal design employs variable block sizes to balance ripple and skip paths, starting with smaller blocks at the least significant bits (prone to carry generation) and larger ones toward the most significant bits, minimizing the longest propagation path. For a 16-bit example, blocks of 2, 3, 5, and 6 bits allow carries to skip via chained logic: if the first block's , its feeds the second block directly; subsequent skips compound if multiple , with the overall propagate for skips computed as the AND of individual block propagates in an OR-configured bypass chain. This structure ensures efficient carry flow without full parallel generation.[52] Advantages include a moderate area overhead of 10-20% over the ripple-carry adder, stemming from the added multiplexers and propagate AND trees (about 1-2 gates per bit), while delivering 2-4x speedups in average cases for medium-word lengths. These trade-offs made carry-skip adders suitable for early microprocessors seeking improved throughput without excessive complexity.[53]Carry-Lookahead Adder

The carry-lookahead adder (CLA) addresses the propagation delay inherent in ripple-carry adders by computing carry bits in parallel rather than sequentially. Introduced by Arnold Weinberger and John L. Smith in 1958, the design uses logical expressions to predict carries based on input bits, enabling faster multi-bit addition.[29] This approach was notably implemented in the arithmetic units of the IBM System/360 Model 91, where it supported high-speed operations in early commercial computing systems.[54] At its core, the CLA employs generate and propagate signals for each bit position . The generate signal indicates if a carry is produced at that bit regardless of the incoming carry: . The propagate signal determines if an incoming carry will propagate to the next bit: . The carry-out for the next bit is then . For multi-bit operations, this recurses to express higher carries directly in terms of inputs: These equations allow all carries to be computed simultaneously using combinational logic, bypassing the sequential ripple. The sum bits are generated using standard full-adder logic: .[55][56] For wider adders, the basic CLA is extended into blocks, typically grouping bits into 4-bit CLA units with internal lookahead logic. Each block computes local carries and also produces group-level generate and propagate signals, which are then fed into a higher-level lookahead stage to compute "super-carries" between blocks. This hierarchical structure cascades efficiently for 16-bit or 32-bit widths while keeping fan-in manageable.[57] The delay of a CLA is for -bit addition under fan-out constraints, as each lookahead level roughly doubles the effective width; for example, a 4-bit CLA achieves full computation in approximately 4 gate delays, compared to for ripple-carry. However, the gate count grows quadratically with width due to the expanding terms in the carry expressions, necessitating hierarchical blocks to mitigate wiring and area issues in large designs.[3][58]Advanced Binary Adders

Carry-Save Adder

A carry-save adder (CSA) is a digital circuit designed to compute the sum of three n-bit binary numbers A, B, and C, producing two n-bit outputs: a sum vector S and a carry vector K, without any carry propagation between bit positions. This structure treats each bit independently, enabling parallel computation across all bits with a fixed delay regardless of operand width. The CSA functions as an array of 3:2 reducers, effectively compressing three input vectors into two output vectors that represent the same total value as S + 2K (where the factor of 2 accounts for the left-shifted alignment of K). The operation of a CSA relies on the standard full-adder logic applied bit-wise. For each bit position i, the sum bit is calculated as , and the carry bit is generated as , where the majority function maj outputs 1 if at least two of the three inputs are 1 (equivalently, ). The carry vector K has its least significant bit set to 0, and it is positioned one bit higher than the sum vector S during subsequent processing. This bit-independent computation avoids the ripple effect seen in traditional adders, resulting in a constant O(1) delay per CSA stage.[55] CSAs are primarily employed in multi-operand addition scenarios, such as the partial product reduction phase in parallel multipliers like the Wallace tree, where they enable efficient logarithmic-depth reduction of multiple summands. In a Wallace tree multiplier, introduced by C. S. Wallace, successive layers of CSAs compress the array of partial products from the AND gate outputs into two final vectors, which are then merged using a carry-propagate adder to yield the product. This approach significantly reduces the overall latency for large multiplications by allowing parallel reduction without sequential carry chains. The key advantages of CSAs include high throughput in pipelined or array-based designs and scalability for wide operands, as the delay per reduction level remains constant, facilitating O(log n) total delay in tree structures for n operands. They are particularly impactful in high-speed VLSI arithmetic units, where the absence of carry propagation minimizes power dissipation and area overhead compared to fully propagating adders in intermediate stages. Implementation involves a straightforward linear array of full adders—one per bit—with inputs connected directly to the corresponding bits of A, B, and C, and outputs forming S and the shifted K; no inter-bit wiring for carries is required. As a representative example, consider a 4-bit CSA adding three numbers such as A = 1011_2 (11_{10}), B = 0110_2 (6_{10}), and C = 1100_2 (12_{10}). Bit-wise application yields S = 0001_2 (1_{10}) and K = 1110_2 (with LSB 0 implied, representing carries to positions 1–4 as 0,1,1,1). The equivalent value is preserved as S + 2K = 1 + 2 \times 14 = 29_{10}, and a final carry-propagate adder combines the aligned vectors to produce the correct 5-bit sum 11101_2 (29_{10}). This demonstrates how the CSA defers normalization to a later stage, optimizing for parallel multi-operand scenarios.[59]Prefix Adders

Prefix adders, also known as parallel prefix adders, employ a tree-based structure to compute generate and propagate signals across bit spans, enabling scalable carry generation for wide binary addition in constant or logarithmic time relative to operand width. This approach addresses the limitations of basic carry-lookahead adders by formulating carry computation as a parallel prefix problem, where associative operators efficiently merge signals from disjoint bit groups. The design consists of three stages: preprocessing to compute local generate (G) and propagate (P) bits, a prefix tree to combine these into group signals, and postprocessing to derive final carries and sums. In the prefix model, black cells initially compute G and P pairs for individual bits, similar to those in carry-lookahead adders. The prefix operator (•) then merges pairs across spans from higher index i to lower index j (i > j):This operator is associative, allowing tree-based parallel evaluation without intermediate dependencies beyond the tree depth.[60][61] Common topologies include the Ladner-Fischer adder, which balances fan-out for moderate area and speed; the Brent-Kung adder, which minimizes area through a two-level hierarchy of odd-even reductions; and the Kogge-Stone adder, which achieves minimal prefix depth at the cost of dense wiring and higher fan-out. These structures vary in parallelism: Ladner-Fischer reduces fan-out by allowing larger spans early, Brent-Kung prioritizes regularity for VLSI layout, and Kogge-Stone uses uniform doubling for fastest propagation.[60][61] The delay of prefix adders is O(log n) for n-bit operands, determined by the prefix tree depth and fan-out constraints, with higher parallelism reducing stages but increasing wiring complexity. For instance, a 64-bit Kogge-Stone adder typically requires 12 logic stages in gate-level implementations, including pre- and postprocessing. These adders excel in high-speed applications, such as integer execution units in processors, where trade-offs favor speed over area; they are employed in high-performance CPUs like AMD's Zen architecture for efficient wide additions. However, denser trees like Kogge-Stone incur higher area and power due to extensive interconnects, while sparser designs like Brent-Kung suit area-constrained scenarios.[62][63] Modern variants hybridize prefix trees with carry-lookahead logic in subdivided blocks to further optimize area-delay products for very wide adders, such as combining Kogge-Stone for critical paths and CLA for peripheral bits.[64][65]

![Full adder with inverted outputs with single-transistor carry propagation delay in CMOS[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Inverting_full_adder_CMOS_24T.svg/250px-Inverting_full_adder_CMOS_24T.svg.png)