Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Compact disc

View on Wikipedia

| |

The readable surface of a compact disc is iridescent because it includes a spiral track wound tightly enough to cause light to diffract into a full visible spectrum. | |

| Media type | Optical disc |

|---|---|

| Capacity |

|

| Read mechanism | 780 nm laser diode |

| Write mechanism | 780 nm laser diode |

| Standard | Rainbow Books |

| Developed by | Philips · Sony |

| Dimensions |

|

| Usage | |

| Extended from | LaserDisc |

| Extended to | |

| Released | |

| Optical discs |

|---|

The compact disc (CD) is a digital optical disc data storage format co-developed by Philips and Sony to store and play digital audio recordings. It employs the Compact Disc Digital Audio (CD-DA) standard and is capable of holding uncompressed stereo audio. First released in Japan in October 1982, the CD was the second optical disc format to reach the market, following the larger LaserDisc (LD). In later years, the technology was adapted for computer data storage as CD-ROM and subsequently expanded into various writable and multimedia formats. As of 2007[update], over 200 billion CDs (including audio CDs, CD-ROMs, and CD-Rs) had been sold worldwide.

Standard CDs have a diameter of 120 millimetres (4.7 inches) and typically hold up to 74 minutes of audio or approximately 650 MiB (681,574,400 bytes) of data. This was later regularly extended to 80 minutes or 700 MiB (734,003,200 bytes) by reducing the spacing between data tracks, with some discs unofficially reaching up to 99 minutes or 870 MiB (912,261,120 bytes) which falls outside established specifications. Smaller variants, such as the Mini CD, range from 60 to 80 millimetres (2.4 to 3.1 in) in diameter and have been used for CD singles or distributing device drivers and software.

The CD gained widespread popularity in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By 1991, it had surpassed the phonograph record and the cassette tape in sales in the United States, becoming the dominant physical audio format. By 2000, CDs accounted for 92.3% of the U.S. music market share.[2] The CD is widely regarded as the final dominant format of the album era, before the rise of MP3, digital downloads, and streaming platforms in the mid-2000s led to its decline.[3]

Beyond audio playback, the compact disc was adapted for general-purpose data storage under the CD-ROM format, which initially offered more capacity than contemporary personal computer hard disk drives. Additional derived formats include write-once discs (CD-R), rewritable media (CD-RW), and multimedia applications such as Video CD (VCD), Super Video CD (SVCD), Photo CD, Picture CD, Compact Disc Interactive (CD-i), Enhanced Music CD, and Super Audio CD (SACD), the latter of which can include a standard CD-DA layer for backward compatibility.

History

[edit]The optophone, first presented in 1913, was an early device that used light for both recording and playback of sound signals on a transparent photograph.[4] More than thirty years later, American inventor James T. Russell has been credited with inventing the first system to record digital media on a photosensitive plate. Russell's patent application was filed in 1966, and he was granted a patent in 1970.[5] Following litigation, Sony and Philips licensed Russell's patents for recording in 1988.[6][7] It is debatable whether Russell's concepts, patents, and prototypes instigated and in some measure influenced the compact disc's design.[8]

The compact disc is an evolution of LaserDisc technology,[9] where a focused laser beam is used that enables the high information density required for high-quality digital audio signals. Unlike the prior art by Optophonie and James Russell, the information on the disc is read from a reflective layer using a laser as a light source through a protective substrate. Prototypes were developed by Philips and Sony independently in the late 1970s.[10] Although originally dismissed by Philips Research management as a trivial pursuit,[11] the CD became the primary focus for Philips as the LaserDisc format struggled.[12]

In 1979, Sony and Philips set up a joint task force of engineers to design a new digital audio disc. The group of experts analyzed every detail of the proposed CD system and meet every two months alternating between Eindhoven and Tokyo for discussions. Each time, the experiments conducted were discussed and the best solution was chosen from the prototypes developed by Sony and Philips. After experimentation, the group decided to adopt Sony’s error correction system, CIRC. Immink, in a few months' time, developed the recording code called eight-to-fourteen modulation (EFM). EFM increases the playing time by more than 30% compared to the code used in the Philips prototype, without causing any issues with tracking. Sony and Philips decide to include EFM in the official Philips/Sony CD standard.[11] EFM and Sony’s error correction code, CIRC are the only standard essential patents, (SEP)s, of the compact disc.

After a year of experimentation and discussion, the Red Book CD-DA standard was published in 1980. After their commercial release in 1982, compact discs and their players were extremely popular. Despite costing up to $1,000, over 400,000 CD players were sold in the United States between 1983 and 1984.[13] By 1988, CD sales in the United States surpassed those of vinyl LPs, and, by 1992, CD sales surpassed those of prerecorded music-cassette tapes.[14][15] The success of the compact disc has been credited to the cooperation between Philips and Sony, which together agreed upon and developed compatible hardware. The unified design of the compact disc allowed consumers to purchase any disc or player from any company and allowed the CD to dominate the at-home music market unchallenged.[16]

Digital audio laser-disc prototypes

[edit]In 1974, Lou Ottens, director of the audio division of Philips, started a small group to develop an analog optical audio disc with a diameter of 20 cm (7.9 in) and a sound quality superior to that of the vinyl record.[17] However, due to the unsatisfactory performance of the analog format, two Philips research engineers recommended a digital format in March 1974. In 1977, Philips then established a laboratory with the mission of creating a digital audio disc. The diameter of Philips's prototype compact disc was set at 11.5 cm (4.5 in), the diagonal of an audio cassette.[9][18]

Heitaro Nakajima, who developed an early digital audio recorder within Japan's national public broadcasting organization, NHK, in 1970, became general manager of Sony's audio department in 1971. In 1973, his team developed a digital PCM adaptor that made audio recordings using a Betamax video recorder. After this, in 1974 the leap to storing digital audio on an optical disc was easily made.[19] Sony first publicly demonstrated an optical digital audio disc in September 1976. A year later, in September 1977, Sony showed the press a 30 cm (12 in) disc that could play an hour of digital audio (44,100 Hz sampling rate and 16-bit resolution) using modified frequency modulation encoding.[20]

In September 1978, Sony demonstrated an optical digital audio disc with a diameter of 30 cm (12 in) with a 150-minute playing time, 44,056 Hz sampling rate, 16-bit linear resolution, and cross-interleaved Reed-Solomon coding (CIRC) error correction code—specifications similar to those later settled upon for the standard compact disc format in 1980. Technical details of Sony's digital audio disc were presented during the 62nd AES Convention, held on 13–16 March 1979, in Brussels.[21] Sony's AES technical paper was published on 1 March 1979. A week later, on 8 March, Philips publicly demonstrated a prototype of an optical digital audio disc at a press conference called "Philips Introduce Compact Disc"[22] in Eindhoven, Netherlands.[23] Sony executive Norio Ohga, later CEO and chairman of Sony, and Heitaro Nakajima were convinced of the format's commercial potential and pushed further development despite widespread skepticism.[24]

Collaboration and standardization

[edit]

In 1979, Sony and Philips set up a joint task force of engineers to design a new digital audio disc. Led by engineers Kees Schouhamer Immink and Toshitada Doi, the research pushed forward laser and optical disc technology.[25] After a year of experimentation and discussion, the task force produced the Red Book CD-DA standard. First published in 1980, the standard was formally adopted by the IEC as an international standard in 1987, with various amendments becoming part of the standard in 1996.[citation needed]

Philips coined the term compact disc in line with another audio product, the Compact Cassette,[26] and contributed the general manufacturing process, based on video LaserDisc technology. Philips also contributed eight-to-fourteen modulation (EFM), while Sony contributed the error-correction method, CIRC, which offers resilience to defects such as scratches and fingerprints.

The Compact Disc Story,[27] told by a former member of the task force, gives background information on the many technical decisions made, including the choice of the sampling frequency, playing time, and disc diameter. The task force consisted of around 6 persons,[11][28] though according to Philips, the compact disc was "invented collectively by a large group of people working as a team".[29]

Initial launch and adoption

[edit]Early milestones in the launch and adoption of the format included:

- The first test pressing was of a recording of Richard Strauss's An Alpine Symphony, recorded December 1–3, 1980 and played by the Berlin Philharmonic and conducted by Herbert von Karajan, who had been enlisted as an ambassador for the format in 1979.[30]

- The world presentation took place during the Salzburg Easter Festival on 15 April 1981, at a press conference of Akio Morita and Norio Ohga (Sony), Joop van Tilburg (Philips), and Richard Busch (PolyGram), in the presence of Karajan who praised the new format.[31]

- The first public demonstration was on the BBC television programme Tomorrow's World in 1981, when the Bee Gees' album Living Eyes (1981) was played.[32]

- The first commercial compact disc was produced on 17 August 1982, a 1979 recording of Chopin waltzes performed by Claudio Arrau.[33]

- The first 50 titles were released in Japan on 1 October 1982,[34] the first of which was a re-release of Billy Joel's 1978 album 52nd Street.[35]

- The first CD played on BBC Radio was in October 1982.[citation needed]

- The Japanese launch was followed on 14 March 1983 by the introduction of CD players and discs to Europe[36] and North America where CBS Records released sixteen titles.[37]

The first artist to sell a million copies on CD was Dire Straits, with their 1985 album Brothers in Arms.[38] One of the first CD markets was devoted to reissuing popular music whose commercial potential was already proven. The first major artist to have their entire catalog converted to CD was David Bowie, whose first fourteen studio albums (up to Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)) of (then) sixteen were made available by RCA Records in February 1985, along with four greatest hits albums; his fifteenth and sixteenth albums (Let's Dance and Tonight, respectively) had already been issued on CD by EMI Records in 1983 and 1984, respectively.[39] On 26 February 1987, the first four UK albums by the Beatles were released in mono on compact disc.[40]

The growing acceptance of the CD in 1983 marked the beginning of the popular digital audio revolution.[41] It was enthusiastically received, especially in the early-adopting classical music and audiophile communities, and its handling quality received particular praise. As the price of players gradually came down, and with the introduction of the portable Discman, the CD began to gain popularity in the larger popular and rock music markets. With the rise in CD sales, pre-recorded cassette tape sales began to decline in the late 1980s; CD sales overtook cassette sales in the early 1990s.[42][43] In 1988, 400 million CDs were manufactured by 50 pressing plants around the world.[44]

Further development

[edit]

Early CD players employed binary-weighted digital-to-analog converters (DAC), which contained individual electrical components for each bit of the DAC.[45] Even when using high-precision components, this approach was prone to decoding errors.[clarification needed][45] Another issue was jitter, a time-related defect. Confronted with the instability of DACs, manufacturers initially turned to increasing the number of bits in the DAC and using several DACs per audio channel, averaging their output.[45] This increased the cost of CD players but did not solve the core problem.

A breakthrough in the late 1980s culminated in development of the 1-bit DAC, which converts high-resolution low-frequency digital input signal into a lower-resolution high-frequency signal that is mapped to voltages and then smoothed with an analog filter. The temporary use of a lower-resolution signal simplified circuit design and improved efficiency, which is why it became dominant in CD players starting from the early 1990s. Philips used a variation of this technique called pulse-density modulation (PDM),[46] while Matsushita (now Panasonic) chose pulse-width modulation (PWM), advertising it as MASH, which is an acronym derived from their patented Multi-stAge noiSe-sHaping PWM topology.[45]

The CD was primarily planned as the successor to the vinyl record for playing music, rather than as a data storage medium. However, CDs have grown to encompass other applications. In 1983, following the CD's introduction, Immink and Joseph Braat presented the first experiments with erasable compact discs during the 73rd AES Convention.[47] In June 1985, the computer-readable CD-ROM (read-only memory) and, in 1990, recordable CD-R discs were introduced.[a] Recordable CDs became an alternative to tape for recording and distributing music and could be duplicated without degradation in sound quality.

Other newer video formats such as DVD and Blu-ray use the same physical geometry as CD, and most DVD and Blu-ray players are backward compatible with audio CDs.

Peak

[edit]CD sales in the United States peaked by 2000.[48] By the early 2000s, the CD player had largely replaced the audio cassette player as standard equipment in new automobiles, with 2010 being the final model year for any car in the United States to have a factory-equipped cassette player.[49]

Two new formats were marketed in the 2000s designed as successors to the CD: the Super Audio CD (SACD) and DVD-Audio. However neither of these were adopted partly due to increased relevance of digital (virtual) music and the apparent lack of audible improvements in audio quality to most human ears.[50] These effectively extended the CD's longevity in the music market.[51]

Decline

[edit]With the advent and popularity of Internet-based distribution of files in lossy-compressed audio formats such as MP3, sales of CDs began to decline in the 2000s. For example, between 2000 and 2008, despite overall growth in music sales and one anomalous year of increase, major-label CD sales declined overall by 20%.[52] Despite rapidly declining sales year-over-year, the pervasiveness of the technology lingered for a time, with companies placing CDs in pharmacies, supermarkets, and filling station convenience stores to target buyers less likely to be able to use Internet-based distribution.[12]

In 2012, CDs and DVDs made up only 34% of music sales in the United States.[53] By 2015, only 24% of music in the United States was purchased on physical media, two thirds of this consisting of CDs;[54] however, in the same year in Japan, over 80% of music was bought on CDs and other physical formats.[55] In 2018, U.S. CD sales were 52 million units—less than 6% of the peak sales volume in 2000.[48] In the UK, 32 million units were sold, almost 100 million fewer than in 2008.[56] In 2018, Best Buy announced plans to decrease their focus on CD sales, however, while continuing to sell records, sales of which are growing during the vinyl revival.[57][58][59]

During the 2010s, the increasing popularity of solid-state media and music streaming services caused automakers to remove automotive CD players in favor of minijack auxiliary inputs, wired connections to USB devices and wireless Bluetooth connections.[60] Automakers viewed CD players as using up valuable space and taking up weight which could be reallocated to more popular features, like large touchscreens.[61] By 2021, only Lexus and General Motors were still including CD players as standard equipment with certain vehicles.[61]

Current status

[edit]CDs continued to be strong in some markets such as Japan where 132 million units were produced in 2019.[62]

The decline in CD sales has slowed in recent years; in 2021, CD sales increased in the US for the first time since 2004,[63] with Axios citing its rise to "young people who are finding they like hard copies of music in the digital age".[64] It came at the same time as both vinyl and cassette reached sales levels not seen in 30 years.[65] The RIAA reported that CD revenue made a dip in 2022, before increasing again in 2023 and overtook downloading for the first time in over a decade.[66]

In the US, 33.4 million CD albums were sold in the year 2022.[67] In France in 2023, 10.5 million CDs were sold, almost double that of vinyl, but both of them represented generated 12% each of the French music industry revenues.[68]

Awards and accolades

[edit]Sony and Philips received praise for the development of the compact disc from professional organizations. These awards include:

- Technical Grammy Award for Sony and Philips, 1998.[69]

- IEEE Milestone award, 2009, for Philips alone with the citation: "On 8 March 1979, N.V. Philips' Gloeilampenfabrieken demonstrated for the international press a Compact Disc Audio Player. The demonstration showed that it is possible by using digital optical recording and playback to reproduce audio signals with superb stereo quality. This research at Philips established the technical standard for digital optical recording systems."[70]

Physical details

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) |

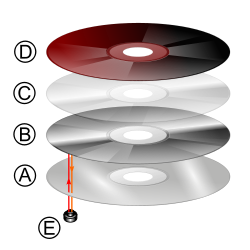

- A polycarbonate disc layer has the data encoded by using bumps.

- A shiny layer reflects the laser.

- A layer of lacquer protects the shiny layer.

- Artwork is screen printed on the top of the disc.

- A laser beam is reflected off the CD to a sensor, which converts it into electronic data.

A CD is made from 1.2-millimetre (0.047 in) thick, polycarbonate plastic, and weighs 14–33 grams.[71] From the center outward, components are: the center spindle hole (15 mm), the first-transition area (clamping ring), the clamping area (stacking ring), the second-transition area (mirror band), the program (data) area, and the rim. The inner program area occupies a radius from 25 to 58 mm.

A thin layer of aluminum or, more rarely, gold is applied to the surface, making it reflective. The metal is protected by a film of lacquer normally spin coated directly on the reflective layer. The label is printed on the lacquer layer, usually by screen printing or offset printing.

CD data is represented as tiny indentations known as pits, encoded in a spiral track molded into the top of the polycarbonate layer. The areas between pits are known as lands. Each pit is approximately 100 nm deep by 500 nm wide, and varies from 850 nm to 3.5 μm in length.[72] The distance between the windings (the pitch) is 1.6 μm (measured center-to-center, not between the edges).[73][74][75]

When playing an audio CD, a motor within the CD player spins the disc to a scanning velocity of 1.2–1.4 m/s (constant linear velocity, CLV)—equivalent to approximately 500 RPM at the inside of the disc, and approximately 200 RPM at the outside edge.[76] The track on the CD begins at the inside and spirals outward so a disc played from beginning to end slows its rotation rate during playback.

The program area is 86.05 cm2 and the length of the recordable spiral is 86.05 cm2 / 1.6 μm = 5.38 km. With a scanning speed of 1.2 m/s, the playing time is 74 minutes or 650 MiB of data on a CD-ROM. A disc with data packed slightly more densely is tolerated by most players (though some old ones fail). Using a linear velocity of 1.2 m/s and a narrower track pitch of 1.5 μm increases the playing time to 80 minutes, and data capacity to 700 MiB. Even denser tracks are possible, with semi-standard 90 minute/800 MiB discs having 1.33 μm, and 99 minute/870 MiB having 1.26 μm,[77] but compatibility suffers as density increases.

A CD is read by focusing a 780 nm wavelength (near infrared) semiconductor laser (early players used He–Ne laser[78]) through the bottom of the polycarbonate layer. The change in height between pits and lands results in a difference in the way the light is reflected. Because the pits are indented into the top layer of the disc and are read through the transparent polycarbonate base, the pits form bumps when read.[79] The laser hits the disc, casting a circle of light wider than the modulated spiral track reflecting partially from the lands and partially from the top of any bumps where they are present. As the laser passes over a pit (bump), its height means that the round trip path of the light reflected from its peak is 1/2 wavelength out of phase with the light reflected from the land around it. This is because the height of a bump is around 1/4 of the wavelength of the light used, so the light falls 1/4 out of phase before reflection and another 1/4 wavelength out of phase after reflection. This causes partial cancellation of the laser's reflection from the surface. By measuring the reflected intensity change with a photodiode, a modulated signal is read back from the disc.[76]

To accommodate the spiral pattern of data, the laser is placed on a mobile mechanism within the disc tray of any CD player. This mechanism typically takes the form of a sled that moves along a rail. The sled can be driven by a worm gear or linear motor. Where a worm gear is used, a second shorter-throw linear motor, in the form of a coil and magnet, makes fine position adjustments to track eccentricities in the disk at high speed. Some CD drives (particularly those manufactured by Philips during the 1980s and early 1990s) use a swing arm similar to that seen on a gramophone.

The pits and lands do not directly represent the 0s and 1s of binary data. Instead, non-return-to-zero, inverted encoding is used: a change from either pit to land or land to pit indicates a 1, while no change indicates a series of 0s. There must be at least two, and no more than ten 0s between each 1, which is defined by the length of the pit. This, in turn, is decoded by reversing the eight-to-fourteen modulation used in mastering the disc, and then reversing the cross-interleaved Reed–Solomon coding, finally revealing the raw data stored on the disc. These encoding techniques (defined in the Red Book) were originally designed for CD Digital Audio, but they later became a standard for almost all CD formats (such as CD-ROM).

Integrity

[edit]CDs are susceptible to damage during handling and from environmental exposure. Pits are much closer to the label side of a disc, enabling defects and contaminants on the clear side to be out of focus during playback. Consequently, CDs are more likely to suffer damage on the label side of the disc. Scratches on the clear side can be repaired by refilling them with similar refractive plastic or by careful polishing. The edges of CDs are sometimes incompletely sealed, allowing gases and liquids to enter the CD and corrode the metal reflective layer and/or interfere with the focus of the laser on the pits, a condition known as disc rot.[80] The fungus Geotrichum candidum has been found—under conditions of high heat and humidity—to consume the polycarbonate plastic and aluminium found in CDs.[81][82]

The data integrity of compact discs can be measured using surface error scanning, which can measure the rates of different types of data errors, known as C1, C2, CU and extended (finer-grain) error measurements known as E11, E12, E21, E22, E31 and E32, of which higher rates indicate a possibly damaged or unclean data surface, low media quality, deteriorating media and recordable media written to by a malfunctioning CD writer.

Error scanning can reliably predict data losses caused by media deterioration. Support of error scanning differs between vendors and models of optical disc drives, and extended error scanning (known as "advanced error scanning" in Nero DiscSpeed) which reports the six aforementioned E-type errors has only been available on Plextor and some BenQ optical drives so far, as of 2020.[83][84]

Disc shapes and diameters

[edit]

* Some CD-R(W) and DVD-R(W)/DVD+R(W) recorders operate in ZCLV, CAA or CAV modes.

The digital data on a CD begins at the inside near the spindle hole and spirals outward toward the edge in a single track. The outward spiral allows adaptation to different-sized discs. Standard CDs are available in two sizes. By far, the most common is 120 millimetres (4.7 in) in diameter, with a 74-, 80, 90, or 99-minute audio capacity and a 650, 700, 800, or 870 MiB (737,280,000-byte) data capacity. Discs are 1.2 millimetres (0.047 in) thick, with a 15 millimetres (0.59 in) center hole. The size of the hole was chosen by Joop Sinjou and based on a Dutch 10-cent coin: a dubbeltje.[85] Philips/Sony patented the physical dimensions.[86]

The official Philips history says the capacity was specified by Sony executive Norio Ohga to be able to contain the entirety of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on one disc.[87] According to Philips chief engineer Kees Immink, this is a myth,[88] as the EFM code format had not yet been decided in December 1979, when the 120 mm size was adopted. The adoption of EFM in June 1980 allowed 30 percent more playing time that would have resulted in 97 minutes for 120 mm diameter or 74 minutes for a disc as small as 100 millimetres (3.9 in). Instead, the information density was lowered by 30 percent to keep the playing time at 74 minutes.[89][90] The 120 mm diameter has been adopted by subsequent formats, including Super Audio CD, DVD, HD DVD, and Blu-ray Disc. The 80-millimetre (3.1 in) diameter discs ("Mini CDs") can hold up to 24 minutes of music or 210 MiB.

| Physical size | Audio capacity | CD-ROM data capacity | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 120 mm | 74–80 min | 650–700 MB | Standard size |

| 80 mm | 21–24 min | 185–210 MB | Mini-CD size |

| 80×54 mm – 80×64 mm | ~6 min | 10–65 MB | Business card size |

SHM-CD

[edit]

SHM-CD (short for Super High Material Compact Disc) is a variant of the Compact Disc, which replaces the polycarbonate base with a proprietary material. This material was created during joint research by Universal Music Japan and JVC into manufacturing high-clarity liquid-crystal displays.

SHM-CDs are fully compatible with all CD players since the difference in light refraction is not detected as an error. JVC claims that the greater fluidity and clarity of the material used for SHM-CDs results in a higher reading accuracy and improved sound quality.[91] However, since the CD-Audio format contains inherent error correction, it is unclear whether a reduction in read errors would be great enough to produce an improved output.

Logical format

[edit]Audio CD

[edit]

The logical format of an audio CD (officially Compact Disc Digital Audio or CD-DA) is described in a document produced in 1980 by the format's joint creators, Sony and Philips.[92] The document is known colloquially as the Red Book CD-DA after the color of its cover. The format is a two-channel 16-bit PCM encoding at a 44.1 kHz sampling rate per channel. Four-channel sound was to be an allowable option within the Red Book format, but has never been implemented. Monaural audio has no existing standard on a Red Book CD; thus, the mono source material is usually presented as two identical channels in a standard Red Book stereo track (i.e., mirrored mono); an MP3 CD can have audio file formats with mono sound.

CD-Text is an extension of the Red Book specification for an audio CD that allows for the storage of additional text information (e.g., album name, song name, artist) on a standards-compliant audio CD. The information is stored either in the lead-in area of the CD, where there are roughly five kilobytes of space available or in the subcode channels R to W on the disc, which can store about 31 megabytes.

Compact Disc + Graphics is a special audio compact disc that contains graphics data in addition to the audio data on the disc. The disc can be played on a regular audio CD player, but when played on a special CD+G player, it can output a graphics signal (typically, the CD+G player is hooked up to a television set or a computer monitor); these graphics are almost exclusively used to display lyrics on a television set for karaoke performers to sing along with. The CD+G format takes advantage of the channels R through W. These six bits store the graphics information.

CD + Extended Graphics (CD+EG, also known as CD+XG) is an improved variant of the Compact Disc + Graphics (CD+G) format. Like CD+G, CD+EG uses basic CD-ROM features to display text and video information in addition to the music being played. This extra data is stored in subcode channels R-W. Very few CD+EG discs have been published.

Super Audio CD

[edit]Super Audio CD (SACD) is a high-resolution, read-only optical audio disc format that was designed to provide higher-fidelity digital audio reproduction than the Red Book. Introduced in 1999, it was developed by Sony and Philips, the same companies that created the Red Book. SACD was in a format war with DVD-Audio, but neither has replaced audio CDs. The SACD standard is referred to as the Scarlet Book standard.

Titles in the SACD format can be issued as hybrid discs; these discs contain the SACD audio stream as well as a standard audio CD layer which is playable in standard CD players, thus making them backward compatible.

CD-MIDI

[edit]CD-MIDI is a format used to store music-performance data, which upon playback is performed by electronic instruments that synthesize the audio. Hence, unlike the original Red Book CD-DA, these recordings are not digitally sampled audio recordings. The CD-MIDI format is defined as an extension of the original Red Book.

CD-ROM

[edit]For the first few years of its existence, the CD was a medium used purely for audio. In 1988, the Yellow Book CD-ROM standard was established by Sony and Philips, which defined a non-volatile optical data computer data storage medium using the same physical format as audio compact discs, readable by a computer with a CD-ROM drive.

Video CD

[edit]Video CD (VCD, View CD, and Compact Disc digital video) is a standard digital format for storing video media on a CD. VCDs are playable in dedicated VCD players, most modern DVD-Video players, personal computers, and some video game consoles. The VCD standard was created in 1993 by Sony, Philips, Matsushita, and JVC and is referred to as the White Book standard.

Overall picture quality is intended to be comparable to VHS video. Poorly compressed VCD video can sometimes be of lower quality than VHS video, but VCD exhibits block artifacts rather than analog noise and does not deteriorate further with each use. 352×240 (or SIF) resolution was chosen because it is half the vertical and half the horizontal resolution of the NTSC video. 352×288 is a similarly one-quarter PAL/SECAM resolution. This approximates the (overall) resolution of an analog VHS tape, which, although it has double the number of (vertical) scan lines, has a much lower horizontal resolution.

Super Video CD

[edit]Super Video CD (Super Video Compact Disc or SVCD) is a format used for storing video media on standard compact discs. SVCD was intended as a successor to VCD and an alternative to DVD-Video and falls somewhere between both in terms of technical capability and picture quality.

SVCD has two-thirds the resolution of DVD, and over 2.7 times the resolution of VCD. One CD-R disc can hold up to 60 minutes of standard-quality SVCD-format video. While no specific limit on SVCD video length is mandated by the specification, one must lower the video bit rate, and therefore quality, to accommodate very long videos. It is usually difficult to fit much more than 100 minutes of video onto one SVCD without incurring a significant quality loss, and many hardware players are unable to play a video with an instantaneous bit rate lower than 300 to 600 kilobits per second.

Photo CD

[edit]Photo CD is a system designed by Kodak for digitizing and storing photos on a CD. Launched in 1992, the discs were designed to hold nearly 100 high-quality images, scanned prints, and slides using special proprietary encoding. Photo CDs are defined in the Beige Book and conform to the CD-ROM XA and CD-i Bridge specifications as well. They are intended to play on CD-i players, Photo CD players, and any computer with suitable software (irrespective of operating system). The images can also be printed out on photographic paper with a special Kodak machine. This format is not to be confused with Kodak Picture CD, which is a consumer product in CD-ROM format.

CD-i

[edit]The Philips Green Book specifies a standard for interactive multimedia compact discs designed for CD-i players (1993). CD-i discs can contain audio tracks that can be played on regular CD players, but CD-i discs are not compatible with most CD-ROM drives and software. The CD-i Ready specification was later created to improve compatibility with audio CD players, and the CD-i Bridge specification was added to create CD-i-compatible discs that can be accessed by regular CD-ROM drives.

CD-i Ready

[edit]Philips defined a format similar to CD-i called CD-i Ready, which puts CD-i software and data into the pregap of track 1. This format was supposed to be more compatible with older audio CD players.

Enhanced Music CD (CD+)

[edit]Enhanced Music CD, also known as CD Extra or CD Plus, is a format that combines audio tracks and data tracks on the same disc by putting audio tracks in a first session and data in a second session. It was developed by Philips and Sony, and it is defined in the Blue Book.

VinylDisc

[edit]VinylDisc is the hybrid of a standard audio CD and the vinyl record. The vinyl layer on the disc's label side can hold approximately three minutes of music.

Manufacture, cost, and pricing

[edit]In 1995, material costs were 30 cents for the jewel case and 10 to 15 cents for the CD. The wholesale cost of CDs was $0.75 to $1.15, while the typical retail price of a prerecorded music CD was $16.98.[93] On average, the store received 35 percent of the retail price, the record company 27 percent, the artist 16 percent, the manufacturer 13 percent, and the distributor 9 percent.[93] When 8-track cartridges, compact cassettes, and CDs were introduced, each was marketed at a higher price than the format they succeeded, even though the cost to produce the media was reduced. This was done because the perceived value increased. This continued from phonograph records to CDs, but was broken when Apple marketed MP3s for $0.99, and albums for $9.99. The incremental cost, though, to produce an MP3 is negligible.[94]

Writable compact discs

[edit]Recordable CD

[edit]

Recordable Compact Discs, CD-Rs, are injection-molded with a blank data spiral. A photosensitive dye is then applied, after which the discs are metalized and lacquer-coated. The write laser of the CD recorder changes the color of the dye to allow the read laser of a standard CD player to see the data, just as it would with a standard stamped disc. The resulting discs can be read by most CD-ROM drives and played in most audio CD players. CD-Rs follow the Orange Book standard.

CD-R recordings are designed to be permanent. Over time, the dye's physical characteristics may change causing read errors and data loss until the reading device cannot recover with error correction methods. Errors can be predicted using surface error scanning. The design life is from 20 to 100 years, depending on the quality of the discs, the quality of the writing drive, and storage conditions.[95] Testing has demonstrated such degradation of some discs in as little as 18 months under normal storage conditions.[96][97] This failure is known as disc rot, for which there are several, mostly environmental, reasons.[98]

The recordable audio CD is designed to be used in a consumer audio CD recorder. These consumer audio CD recorders use SCMS (Serial Copy Management System), an early form of digital rights management (DRM), to conform to the AHRA (Audio Home Recording Act). The Recordable Audio CD is typically somewhat more expensive than CD-R due to lower production volume and a 3 percent AHRA royalty used to compensate the music industry for the making of a copy.[99]

High-capacity recordable CD is a higher-density recording format that can hold 20% more data than conventional discs.[100] The higher capacity is incompatible with some recorders and recording software.[101]

ReWritable CD

[edit]CD-RW is a re-recordable medium that uses a metallic alloy instead of a dye. The write laser, in this case, is used to heat and alter the properties (amorphous vs. crystalline) of the alloy, and hence change its reflectivity. A CD-RW does not have as great a difference in reflectivity as a pressed CD or a CD-R, and so many earlier CD audio players cannot read CD-RW discs, although most later CD audio players and stand-alone DVD players can. CD-RWs follow the Orange Book standard.

The ReWritable Audio CD is designed to be used in a consumer audio CD recorder, which will not (without modification) accept standard CD-RW discs. These consumer audio CD recorders use the Serial Copy Management System (SCMS), an early form of digital rights management (DRM), to conform to the United States' Audio Home Recording Act (AHRA). The ReWritable Audio CD is typically somewhat more expensive than CD-R due to (a) lower volume and (b) a 3 percent AHRA royalty used to compensate the music industry for the making of a copy.[99]

Copy protection

[edit]The Red Book audio specification, except for a simple anti-copy statement in the subcode, does not include any copy protection mechanism. Known at least as early as 2001,[102] attempts were made by record companies to market copy-protected non-standard compact discs, which cannot be ripped, or copied, to hard drives or easily converted to other formats (like FLAC, MP3 or Vorbis). One major drawback to these copy-protected discs is that most will not play on either computer CD-ROM drives or some standalone CD players that use CD-ROM mechanisms. Philips has stated that such discs are not permitted to bear the trademarked Compact Disc Digital Audio logo because they violate the Red Book specifications. Numerous copy-protection systems have been countered by readily available, often free, software, or even by simply turning off automatic AutoPlay to prevent the running of the DRM executable program.

See also

[edit]- Comparison of popular optical data-storage systems

- Optical disc packaging

- Extended Resolution Compact Disc

- High Definition Compatible Digital – Proprietary backward-compatible CD audio format

- Compact disc bronzing – Type of compact disc corrosion

- DualDisc – Double-sided optical disc

- Hidden track – Music not detectable by casual listeners

- SPARS code – Classification system for commercial compact disc releases

- List of optical disc manufacturers

References

[edit]- ^ "The Compact Disc (CD) is Developed". historyofinformation.com. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Music Revenue Database". RIAA. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (28 May 2015). "How the compact disc lost its shine". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Das Photo als Schalplatte" (PDF) (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ US 3,501,586, "Analog to digital to optical photographic recording and playback system", published 17 March 1970

- ^ "Inventor and physicist James Russell '53 will receive Vollum Award at Reed's convocation" (Press release). Reed College public affairs office. 2000. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ "Inventor of the Week – James T. Russell – The Compact Disc". MIT. December 1999. Archived from the original on 17 April 2003.

- ^ Brier Dudley (29 November 2004). "Scientist's invention was let go for a song". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ a b K. Schouhamer Immink (1998). "The Compact Disc Story". Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 46 (5): 458–460. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "The History of the CD". Philips Research. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b c K. Schouhamer Immink (2007). "Shannon, Beethoven, and the Compact Disc". IEEE Information Theory Society Newsletter. 57: 42–46. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ a b Straw, Will (2009). "The Music CD and Its Ends". Design and Culture. 1 (1): 79–91. doi:10.2752/175470709787375751. S2CID 191574354.

- ^ Rasen, Edward (May 1985). "Compact Discs: Sound of the Future". Spin. Archived from the original on 16 December 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ Billboard (March 1992). "CD Unit Sales Pass Cassettes, Majors Say". Billboard.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (December 1988). "Have Compact Disks Become Too Much of a Good Thing?". The New York Times.

- ^ Introducing the amazing Compact Disc (1982). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 June 2015. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Kornelis, Chris (27 January 2015). "Why CDs may actually sound better than vinyl]". Archived from the original on 9 April 2016.

- ^ Peek, Hans B. (January 2010). "The Emergence of the Compact Disc". IEEE Communications Magazine. 48 (1): 10–17. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2010.5394021. ISSN 0163-6804. S2CID 21402165.

- ^ McClure, Steve (8 January 2000). "Heitaro Nakajima". Billboard. p. 68. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "A Long Play Digital Audio Disc System". Audio Engineering Society. March 1979. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "A Long Play Digital Audio Disc System". Audio Engineering Society. March 1979. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "How the CD Was Developed". BBC News. 17 August 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ "Philips Compact Disc". Philips. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "Sony chairman credited with developing CDs dies", Fox News, 24 April 2011, archived from the original on 21 May 2013, retrieved 14 October 2012

- ^ "How the CD Was Developed". BBC News. 17 August 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ Peek, Hans B. (January 2010). "The Emergence of the Compact Disc". IEEE Communications Magazine. 48 (1): 10–17. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2010.5394021. ISSN 0163-6804. S2CID 21402165.

- ^ K. Schouhamer Immink (1998). "The Compact Disc Story". Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 46 (5): 458–460. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2018. Cite error: The named reference "Compact Disc Digital Audio Immink" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Knopper, Steve (7 January 2009). Appetite for Self-Destruction: The Rise and Fall of the Record Industry in the Digital Age. Free Press.

- ^ "The Inventor of the CD". Philips Research. Archived from the original on 29 January 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Kelly, Heather (29 September 2012). "Rock on! The compact disc turns 30". CNN. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

The first test CD was Richard Strauss's Eine Alpensinfonie, and the first CD actually pressed at a factory was ABBA's The Visitors, but that disc wasn't released commercially until later.

- ^ "Weltpräsentation des "Compact Disc Digital Audio System" (Audio-CD)". Salzburg. Geschichte. Kultur. (in German). Salzburg: Archiv der Erzdiözese Salzburg. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Bilyeu, Melinda; Hector Cook; Andrew Môn Hughes (2004). The Bee Gees:tales of the brothers Gibb. Omnibus Press. p. 519. ISBN 978-1-84449-057-8.

- ^ 1985 News Story on Debut of the Compact Disc (CD). acmestreamingDOTcom. 20 July 2010. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Sony History: A Great Invention 100 Years On". Sony. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Giles, Jeff (1 October 2012). "How Billy Joel's '52nd Street' Became the First Compact Disc released". Ultimate Classic Rock. Townsquare Media, LLC. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Philips celebrates 25th anniversary of the Compact Disc"Archived 17 August 2015 at Archive-It, Philips Media Release, 16 August 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ Kaptainis, Arthur (5 March 1983). "Sampling the latest sound: should last a lifetime". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. p. E11.

- ^ Maxim, 2004

- ^ The New Schwann Record & Tape Guide Volume 37 No. 2 February 1985

- ^ JON PARELES (25 February 1987). "NOW ON CD'S, FIRST 4 BEATLES ALBUMS". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Canale, Larry (1986). Digital Audio's Guide to Compact Discs. Bantam Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-553-34356-4.

- ^ "When did CD's Take a Front Seat to the Cassette Tape". Kodak Digitizing. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ^ Harlow, Oliva. "When Did the CD Replace the Cassette Tape?". artifact. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ MAC Audio News. No. 178, November 1989. pp 19–21 Glenn Baddeley. November 1989 News Update. Melbourne Audio Club Inc.

- ^ a b c d van Willenswaard, Peter (1 May 1989). "PDM, PWM, Delta-Sigma, 1-Bit DACs". stereophile.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Atkinson, John (1989). "PDM, PWM, Delta-Sigma, 1-Bit DACs by John Atkinson". stereophile.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ K. Schouhamer Immink and J. Braat (1984). "Experiments Toward an Erasable Compact Disc". J. Audio Eng. Soc. 32: 531–538. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ a b Richter, Felix. "The Rise and Fall of the Compact Disc". Statista. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Williams, Stephen (4 February 2011). "For Car Cassette Decks, Play Time Is Over". New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "Journal of the AES » 2007 September - Volume 55 Number 9". www.aes.org (in Slovak). Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Blu-ray is to DVD as SACD was to CD: Better, but not enough better?". CNET. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Smith, Ethan (2 January 2009). "Music Sales Decline for Seventh Time in Eight Years: Digital Downloads Can't Offset 20% Plunge in CD Sales". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ "Buying CDs continues to be a tradition in Japan – Tokyo Times". 23 August 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Friedlander, Joshua P. (2015). "News and Notes on 2015 Mid-Year RIAA Shipment and Revenue Statistics" (PDF). Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2015.

- ^ Sisaro, Ben. New York Times 11 June 2015: Sisario, Ben (11 June 2015). "Music Streaming Service Aims at Japan, Where CD Is Still King". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Is this the end of owning music?", BBC News, 3 January 2019, archived from the original on 8 November 2020, retrieved 3 March 2021

- ^ Ong, Thuy (6 February 2018). "Best Buy will stop selling CDs as digital music revenue continues to grow". The Verge. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Owsinski, Bobby (7 July 2018). "Best Buy, Winding Down CD Sales, Pounds Another Nail Into The Format's Coffin". Forbes. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Chris Morris (2 July 2018). "End of a Era: Best Buy Significantly Cuts Back on CDs". Fortune. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Biersdorfer, J.D. (17 March 2017). "Hand Me the AUX Cord". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ a b Ramey, Jay (9 February 2021). "Do You Want a CD Player in a New Car?". Autoweek. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Physical Formats Still Dominate Japanese Music Market". nippon.com. 24 June 2020. Archived from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "Let's Get Physical! Vinyl Sales up >51%, CD Sales up for First Time in 17-yrs". Strata-gee.com. 26 January 2022. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Kariuki, Patrick (18 March 2022). "CD Sales Are Rising Again, but Why?". Makeuseof.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "Vinyl and cassette UK sales continue to surge to 30 year high". Officialcharts.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Bass, Matthew (2024). Year-end 2023 RIAA Revenue Statistics (PDF) (Report). Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ "Physical album shipments in the U.S. 2022". Statista. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Bazoge, Mickaël (27 March 2024). "En France comme aux États-Unis, les vinyles en position de force face aux CD". 01net.com (in French). Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Technical Grammy Award". Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ "IEEE CD Milestone". IEEE Global History Network. Archived from the original on 26 November 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ Pohlmann, Ken C. (1989). The Compact Disc: A Handbook of Theory and Use. A-R Editions, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89579-228-0.

- ^ "Compact Disc". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Sharpless, Graham (July 2003). "Introduction to CD and CD-ROM" (PDF). Deluxe Global Media Services Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "IEC 60908 Audio recording - Compact disc digital audio system". Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ^ "ISO/IEC 10149 Information technology -- Data interchange on read-only 120 mm optical data disks (CD-ROM)". Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Compact disc (CD) | Definition & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 7 March 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Pencheva, Tamara; Gyoch, Berkant; Mashkov, Petko (1 May 2010). "Optical measurements upon compact discs in education in optoelectronics". Electronics Technology (ISSE), 2010 33rd International Spring Seminar on Electronics Technology. pp. 531–535. ISBN 978-1-4244-7849-1.

- ^ Träger, Frank (5 May 2012). Springer Handbook of Lasers and Optics. Springer. ISBN 9783642194092.

- ^ An Introduction to Digital Audio, John Watkinson, 1994

- ^ Council on Library and Information Resources: Conditions that Affect CDs and DVDs Archived 15 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bosch, Xavier (2001). "Fungus eats CD". Nature. doi:10.1038/news010628-11. ISSN 0028-0836. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Fungus 'eats' CDs". BBC. June 2001. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Philips DVD-R 8x (InfodiscR20) - Philips - Gleitz" (in German). 18 November 2006.

- ^ "QPxTool glossary". qpxtool.sourceforge.io. QPxTool. 1 August 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Perfecting the Compact Disc System - The six Philips/Sony meetings - 1979-1980". DutchAudioClassics.nl. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Response To Koninklijke Philips Electronics, N.V.'s, Sony Corporation of Japan's And Pioneer Electronic Corporation of Japan's Request For Business Review Letter". justice.gov. 25 June 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "Sony chairman credited with developing CDs dies". Fox News. 24 April 2011. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ K.A. Schouhamer Immink (2018). "How we made the compact disc". Nature Electronics. 1. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ K. Schouhamer Immink (2007). "Shannon, Beethoven, and the Compact Disc". IEEE Information Theory Society Newsletter. 57: 42–46. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Tim Buthe and Walter Mattli, The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy, Princeton University Press, Feb. 2011.

- ^ CDJapan. "All About SHM-CD Format". CDJapan. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "IEC 60908:1999 | IEC Webstore". webstore.iec.ch. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ a b Neil Strauss (5 July 1995). "Pennies That Add Up to $16.98: Why CD's Cost So Much – New York Times". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Harmon, Amy (12 October 2003). "MUSIC; What Price Music?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "Cost Per Gigabyte of Popular Data Storage - Infographic". Blank Media Printing. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "CD-R Unreadable in Less Than Two Years". cdfreaks.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- ^ "CD-R ROT". Archived from the original on 4 February 2005. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- ^ "5. Conditions That Affect CDs and DVDs – Council on Library and Information Resources". clir.org. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ a b Andy McFadden (8 August 2007). "CD-Recordable FAQ". Archived from the original on 20 September 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ "Understanding CD-R & CD-RW". Osta.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "CD-Recordable FAQ – Section 3". 9 January 2010. Archived from the original on 18 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

Small quantities of 90-minute and 99-minute blanks have appeared [...] Indications are that many recorders and some software don't work with the longer discs.

- ^ Campaign For Digital Rights (5 December 2001). "Copy Protected CDs". Archived from the original on 5 December 2001.

Further reading

[edit]- Ecma International. Standard ECMA-130: Data Interchange on Read-only 120 mm Optical Data Disks (CD-ROM), 2nd edition (June 1996).

- Pohlmann, Kenneth C. (1992). The Compact Disc Handbook. Middleton, Wisconsin: A-R Editions. ISBN 0-89579-300-8.

- Peek, Hans et al. (2009) Origins and Successors of the Compact Disc. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. ISBN 978-1-4020-9552-8.

- Peek, Hans B., The emergence of the compact disc, IEEE Communications Magazine, Jan. 2010, pp. 10–17.

- Nakajima, Heitaro; Ogawa, Hiroshi (1992) Compact Disc Technology, Tokyo, Ohmsha Ltd. ISBN 4-274-03347-3.

- Barry, Robert (2020). Compact Disc (Object Lessons). New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-5013-4851-8.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The world's first CD-R was made by the Japanese firm Taiyo Yuden Co., Ltd. in 1988 as part of the joint Philips-Sony development effort.

External links

[edit]- Video How Compact Discs are Manufactured

- CD-Recordable FAQ Exhaustive basics on CD-Recordable's

- Philips history of the CD (cache)

- Patent History (CD Player) – published by Philips in 2005

- Patent History CD Disc – published by Philips in 2003

- Sony History, Chapter 8, This is the replacement of Gramophone record ! (第8章 レコードに代わるものはこれだ) – Sony website in Japanese

- Popularized History on Soundfountain

- A Media History of the Compact Disc (1-hour podcast interview)