Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dewclaw

View on Wikipedia

A dewclaw is a digit – vestigial in some animals – on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digitigrade or unguligrade species, it does not make contact with the ground when the animal is standing. The name refers to the dewclaw's alleged tendency to brush dew away from grass.[1] On dogs and cats, the dewclaws are on the inside of the front legs, similarly to a human's thumb, which shares evolutionary homology.[2] Although many animals have dewclaws, other similar species do not, such as horses, giraffes and the African wild dog.

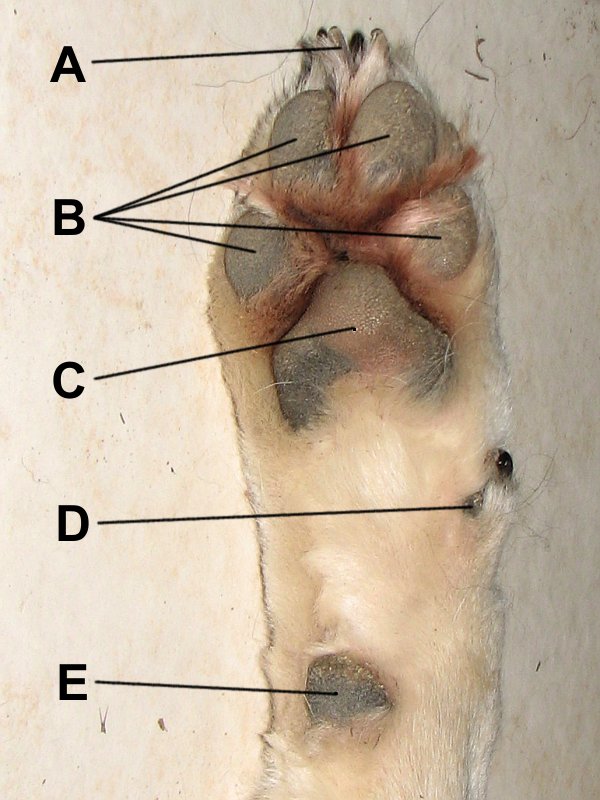

Dogs

[edit]Dogs almost always have dewclaws on the inside of the front legs and occasionally also on the hind legs.[1][3] Unlike front dewclaws, rear dewclaws tend to have little bone or muscle structure in most breeds. For certain dog breeds, a dewclaw is considered a necessity, e.g., a Beauceron for sheep herding and for navigating snowy terrain.[1]

Rear dewclaws

[edit]Canids have four claws on the rear feet,[4] although some domestic dog breeds or individuals have an additional claw, or more rarely two, as is the case with the Beauceron. A more technical term for these additional digits on the rear legs is hind-limb-specific preaxial polydactyly.[5] Several genetic mechanisms can cause rear dewclaws; they involve the LMBR1 gene and related parts of the genome.[5] Rear dewclaws often have no phalanx bones and are attached by skin only.[6]

Dewclaws and locomotion

[edit]Based on stop-action photographs, veterinarian M. Christine Zink of Johns Hopkins University believes that the entire front foot, including the dewclaws, contacts the ground while running. During running, the dewclaw digs into the ground preventing twisting or torque on the rest of the leg. Several tendons connect the front dewclaw to muscles in the lower leg, further demonstrating the front dewclaws' functionality. There are indications that dogs without dewclaws have more foot injuries and are more prone to arthritis. Zink recommends "for working dogs it is best for the dewclaws not to be amputated. If the dewclaw does suffer a traumatic injury, the problem can be dealt with at that time, including amputation if needed."[2]

Cats

[edit]Members of the cat family – including domestic cats[7] and wild cats like the lion[8] – have dewclaws. Generally, a dewclaw grows on the inside of each front leg but not on either hind leg.[9]

The dewclaw on cats is not vestigial. Wild felids use the dewclaw in hunting, where it provides an additional claw with which to catch and hold prey.[8]

Hoofed animals

[edit]

Hoofed animals walk on the tips of special toes, the hooves. Cloven-hoofed animals walk on a central pair of hooves, but many also have an outer pair of dewclaws on each foot. These are somewhat farther up the leg than the main hooves, and similar in structure to them.[10] In some species (such as cattle) the dewclaws are much smaller than the hooves and never touch the ground. In others (such as pigs and many deer), they are only a little smaller than the hooves, and may reach the ground in soft conditions or when jumping. Some hoofed animals (such as giraffes and modern horses) have no dewclaws. Video evidence suggests some animals use dewclaws in grooming or scratching themselves or to have better grasp during mating.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Danziger, D., & McCrum, M. (2008). The Thingummy: A book about those everyday objects you just can't name. London: Doubleday.

- ^ a b Zink, M. Christine. "Form Follows Function – A New Perspective on an Old Adage" (PDF). Penn Vet Working Dog Center. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Rice, Dan (2008). The Complete Book of Dog Breeding (2 ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7641-3887-4.

- ^ Macdonald, D. (1984). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. p. 56. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ^ a b Park, K.; Kang, J.; Subedi, K. P.; Ha, J-H.; Park, C. (August 2008). "Canine Polydactyl Mutations With Heterogeneous Origin in the Conserved Intronic Sequence of LMBR1". Genetics. 179 (4): 2163–2172. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.087114. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 2516088. PMID 18689889.

- ^ Hosgood, Giselle (1998). Small Animal Paediatric Medicine and Surgery. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-7506-3599-8.

- ^ "Clipping a Cat's Claws (Toenails)". Pet Health Topics. Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine. 22 July 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

Cats have a nail on the inner side of each foot called the dew claw. Remember to trim these as they are not worn down when the cat scratches and can grow in a circle, growing into the foot.

- ^ a b "Physiology". Lion ALERT. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

Lions have four claws on their back feet but five on the front where the dew claw is found. This acts like a thumb and is used to hold down prey while the jaws rip away the meat from bone. Set well back from the other claws the dew claw does not appear in the print.

- ^ Bircher, Steve (5 November 2011), Tiger Tales (PDF), National Tiger Sanctuary, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013

- ^ Perich, Shawn; Furman, Michael (2003). Whitetail Hunting: Top-notch Strategies for Hunting North America's Most Popular Big-Game Animal. Creative Publishing international. pp. 8, 9. ISBN 978-1-58923-129-0.

Dewclaw

View on GrokipediaAnatomy and Definition

Structure and Location

A dewclaw is defined as the first digit, equivalent to the hallux on the hindlimb or pollex on the forelimb, located on the medial side of the limbs in many mammals, characteristically non-weight-bearing and reduced in size compared to the primary digits.[4][1] In terms of anatomy, the dewclaw typically consists of a simplified bone structure, often comprising a single phalanx or a rudimentary metacarpal or metatarsal bone, with a claw attached to the distal end. This digit is attached primarily via ligaments and tendons to the surrounding structures, lacking full muscular support, which contributes to its limited mobility and integration with the limb. In carnivorans such as dogs and cats, the forelimb dewclaw is more developed, featuring one or two phalanges firmly connected through a network of connective tissues, while hindlimb dewclaws, when present, may be reduced to just the terminal phalanx and claw, suspended by skin and minimal ligaments.[3][7][8] Dewclaws are commonly positioned above the carpus on the forelimbs and above the hock on the hindlimbs, homologous across species as remnants of the ancestral five-toed limb configuration. In ungulates like cattle and sheep, the dewclaws correspond to digits 2 and 5, appearing as paired accessory structures medial and lateral to the main weight-bearing digits 3 and 4, extending from the fetlock region downward.[9][10] Variations in attachment range from loose suspensions, where the dewclaw dangles freely connected only by skin and proximal ligaments to the pastern or fetlock fascia, to firmer articulations directly with the metacarpal or metatarsal bones via a small joint. For instance, in dogs, forelimb dewclaws often articulate securely with the first metacarpal, whereas hindlimb versions may lack bony union and hang pendulously; in cattle, dewclaws are more rigidly integrated with the distal metacarpus or metatarsus through short ligaments, aiding their alignment with the hoof.[4][11][12]Vestigial Characteristics

Dewclaws form during the early stages of fetal limb bud development in mammals, where the limb initially develops with a pentadactyl (five-digit) pattern similar to ancestral forms, influenced by signaling pathways such as Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and regulatory genes like Patched1. In ungulates like cattle, alterations in Patched1 expression disrupt SHH signaling, leading to symmetrical Hox gene distribution in the limb bud and subsequent reduction of lateral digits into vestigial structures, including dewclaws, which atrophy postnatally due to minimal mechanical loading.[13] In cursorial mammals such as pigs, digit reduction, including the formation of rudimentary dewclaws as reduced second and fifth digits, occurs through modifications in early mesenchymal patterning and gene expression during embryogenesis, rather than later atrophy, resulting in incomplete skeletal elements.[14] Hox genes, particularly from the HoxA and HoxD clusters, play a key role in this process by regulating proximal-distal and anterior-posterior digit identity; their collinear expression ensures initial digit primordia formation, but reduced expression or regulatory changes in vestigial positions lead to atrophy or incomplete development in dewclaws across carnivorans and ungulates.[15] In terms of comparative size, dewclaws are markedly reduced relative to primary weight-bearing digits, with rudimentary bone structure reflecting their vestigial status. For instance, in dogs, the forelimb dewclaw consists of only two phalanges (proximal and distal), lacking the full three-phalange structure of main digits, while hindlimb dewclaws, when present, often feature just a single phalanx or are attached primarily by soft tissue without bony support.[3][11] In cats, the fore dewclaw similarly has two phalanges but is positioned higher on the leg, emphasizing its non-load-bearing role and reduced size compared to the four functional digits.[16] The genetic basis of dewclaw presence and form involves autosomal dominant inheritance patterns, particularly for rear dewclaws in certain breeds. In dogs like the Great Pyrenees, the trait is linked to mutations in the LMBR1 gene on chromosome 16, specifically a G/A substitution in a regulatory sequence (pZRS) that enhances limb-specific expression without altering core signaling, resulting in persistent hindlimb dewclaws as a dominant characteristic.[17] This dominant allele contrasts with the typical absence of rear dewclaws in most canine breeds, where recessive patterns lead to their reduction during development.[18] Pathologically, dewclaws exhibit tendencies toward overgrowth and injury owing to their incomplete integration into the limb structure and lack of natural wear from ground contact. In dogs, dewclaw nails often grow longer and more curved than those on primary digits because they do not abrade against surfaces, leading to embedding or spiraling if untrimmed, which increases susceptibility to trauma such as tears or infections.[19][20] Their thinner attachment and reduced bony support further predispose them to avulsion or overgrowth-related complications, distinct from the robust phalangeal integration of main digits.[21]Dewclaws in Carnivorans

In Dogs

In dogs, dewclaws are the rudimentary first digits located on the inner side of the front legs, homologous to a human thumb, and all domestic dogs are born with them as a standard anatomical feature.[6] Rear dewclaws, when present, appear higher on the hind legs and are less common, occurring in approximately 20 breeds with single rear dewclaws and about 5% of breeds featuring double rear dewclaws, such as the Briard.[22][23] Certain herding breeds mandate the retention of rear dewclaws according to kennel club standards, reflecting their functional heritage; for instance, the American Kennel Club (AKC) requires dewclaws on the Icelandic Sheepdog, with well-developed double dewclaws considered desirable, and faults any absence of them.[24] Similarly, the Briard standard emphasizes double dewclaws on each rear leg as an ancient breed characteristic, with each featuring complete bone structure including proximal and distal phalanges for support.[25][26] These double rear dewclaws in such breeds are firmly attached via bone, muscle, and ligaments, unlike the looser single rear dewclaws in other dogs that connect primarily through skin.[6][8] Dewclaws require regular nail trimming to prevent overgrowth, as their nails grow continuously and do not naturally wear down like those on weight-bearing toes, potentially leading to curling or embedding if neglected.[27] Injury risks include snagging on objects or tears during play, with veterinary studies indicating that broken claws or dewclaws account for a notable portion of nail-related visits—such as 8.84% of nail clipping events in one UK VetCompass analysis of over 2 million dogs from 2019—though overall dewclaw injuries remain relatively rare compared to other digits.[28][29][6] Young dogs aged 1-2 years face higher odds of such issues, often requiring professional clipping in 59.4% of related veterinary consultations.[29] Historically, dewclaws likely aided early domesticated dogs in gripping rough terrain during hunting or herding in ancestral environments, providing extra traction on rocky or uneven ground as dogs evolved from wolf-like progenitors around 15,000-40,000 years ago.[23][30] This trait persisted in working breeds, enhancing stability in challenging landscapes before selective breeding altered prevalence in modern varieties.[27]In Cats

In domestic cats, a single dewclaw is universally present on each front limb, positioned on the medial aspect of the leg near the carpus, while hind dewclaws are occasionally present in some individuals but positioned higher up the leg near the tarsus if developed.[31][32] Unlike in many dogs where rear dewclaws may be absent or rudimentary, feline hind dewclaws, when present, are typically vestigial and not a standard feature.[33] Anatomically, cat dewclaws exhibit stronger tendon and ligament attachments to the surrounding musculature than those in dogs, facilitating partial weight-bearing and enhanced stability during climbing and rapid maneuvers. These attachments, including connections to the extensor and flexor tendons, allow for controlled extension and retraction, supporting the forelimb's role in locomotion, prey capture, and arboreal activities.[34] Relative to paw size, feline dewclaws are larger and more robust than in canines, providing superior grip without compromising agility.[35] Wild felids such as lions and tigers possess dewclaws with similar morphology to domestic cats, primarily utilizing them for prey manipulation, secure grasping during takedowns, and traction on varied terrains. In these species, the forepaw dewclaw functions as an opposable digit akin to a thumb, enabling precise holding of struggling quarry. Domestic cats retain this adaptation for everyday tasks like scratching surfaces, holding toys or prey analogs, and maintaining balance during pouncing or climbing.[31] Dewclaw injuries in cats occur at lower rates than in dogs, attributed to their more integrated limb positioning that reduces exposure to tearing forces during terrestrial activities.[36] This positioning minimizes trauma from impacts, with most issues arising from overgrowth rather than acute damage.[32] However, cats subjected to declawing—a procedure that amputates all terminal phalanges, including the dewclaw—face elevated risks of chronic pain, musculoskeletal imbalances, and behavioral changes such as aggression or avoidance of litter boxes.[37] In felines, vestigial reduction of the dewclaw is less pronounced than in other carnivorans, preserving its practical utility.Dewclaws in Ungulates

In Cattle and Sheep

In cattle and sheep, dewclaws are paired accessory digits present on all four limbs, positioned posterior and proximal to the main weight-bearing hooves at the level of the fetlock joint. These structures consist of a hoof covering two small bones—a proximal ossicle that is irregular or drop-shaped and a distal ossicle that is triangular—forming a prismatic shape overall.[9] In both species, the dewclaws are cloven, mirroring the bifurcation of the primary hooves, though in sheep they often lack full phalangeal development and serve primarily as cutaneous appendages.[39] These digits are homologous to the second and fifth toes in the pentadactyl limb of ancestral ungulates.[4] In cattle, dewclaws are significantly smaller than the main hooves, with variations influenced by breed and individual factors.[40] In show animals, well-formed dewclaws contribute to overall foot conformation assessments under breed standards, where structural soundness is evaluated for competitive exhibition.[41] Genetic defects, such as hypoplasia leading to underdeveloped or absent dewclaws, occur in certain cattle lines, with reported prevalence around 34% in examined populations, often linked to inherited anomalies.[42] In agricultural settings, dewclaws require regular trimming as part of routine hoof care to prevent overgrowth, which can lead to trauma or secondary infections. Dairy cattle undergo more frequent inspections and trims—typically every 4–6 months—due to higher lameness risks in intensive systems, while beef cattle receive less regular attention, often only as needed during handling.[43] Overgrown dewclaws are clipped to maintain balance and reduce injury risk during movement.[43] Compared to cattle, sheep dewclaws show a range of abnormalities, including curved, diverging, L-shaped, and hypoplastic forms, with prevalence around 25% in surveyed flocks, potentially exacerbated by environmental factors affecting hoof integrity.[44] These issues, such as splitting or overgrowth, arise more readily in sheep due to differences in keratin composition and hoof structure, necessitating vigilant trimming in pastoral management.[42]In Other Hoofed Species

In equids, such as horses, dewclaws are absent as a result of evolutionary reduction, with the second and fourth metacarpal and metatarsal bones persisting as small, rudimentary splint bones that serve as structural homologues to the lost digits.[45] These splint bones provide minimal support and are often prone to inflammation or injury in domesticated horses, but in wild equids, their vestigial nature reflects adaptations for high-speed cursorial locomotion on firm terrain.[46] The complete loss of dewclaws in modern equids contrasts with more primitive perissodactyls, where such digits were more prominent for stability.[47] Cervids, including deer and elk, retain reduced dewclaws positioned above the main hooves, which aid in balance and traction during movement across varied landscapes. In these species, the dewclaws contact the ground during rapid acceleration or on soft substrates, helping to prevent slipping and distribute weight for improved stability.[48] For instance, in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), a cervid adapted to arctic environments, the dewclaws function to stabilize the hoof against over-extension and enhance propulsion in snow, effectively enlarging the foot's surface area like snowshoes.[49] While dewclaws in cervids do not undergo seasonal shedding themselves, the overall foot morphology in antlered species like reindeer adapts seasonally, with hardened pads and extended dewclaw use in winter for digging through ice and snow.[50] Among other ungulates, giraffids such as giraffes lack dewclaws entirely, consistent with their highly specialized even-toed foot structure featuring only two main digits per foot for efficient weight-bearing on elongated limbs.[47] In contrast, suids like pigs possess functional dewclaws adjacent to their main trotter hooves, which provide supplementary support during locomotion on uneven or soft ground, reducing stress on the primary digits and improving overall gait efficiency.[51] These dewclaws bear weight intermittently, particularly when pigs accelerate or navigate rough terrain, and their maintenance is crucial for preventing lameness.[52] In wild ungulate populations, dewclaw injuries pose significant conservation challenges by compromising mobility and foraging ability, often increasing susceptibility to predation or starvation. For example, trauma to dewclaws in cervids from rough terrain or conflicts can lead to limping and reduced evasion speeds, contributing to higher mortality rates in vulnerable habitats.[53] Such injuries highlight the importance of intact accessory digits for survival in natural environments, where veterinary intervention is unavailable.[54]Functions and Adaptations

Role in Locomotion

In carnivorans, dewclaws on the forelimbs play a key role in stabilizing the carpus during dynamic movements such as cantering, galloping, and jumping, where they contact the ground to provide additional support and prevent slippage.[2] Specifically in dogs, the dewclaw digs into the substrate during turns, reducing torque on the carpal joint and proximal limb by anchoring the leg and distributing forces more evenly across the forelimb.[2] This biomechanical function is supported by the dewclaw's connection to four tendons that link to distal limb muscles, enabling it to contribute actively to limb stability rather than remaining passive.[2] Dewclaws enhance terrain adaptation by improving grip on uneven, slippery, or soft surfaces, which is particularly evident in agile species. In dogs navigating snowy or icy environments, the forelimb dewclaws act like ice picks to facilitate climbing and prevent forward slippage, allowing for safer traversal of challenging landscapes.[2] Similarly, in cats, the dewclaw aids in climbing by providing extra traction and grip on vertical or irregular surfaces, such as tree bark or rocks, during ascent or descent, thereby supporting precise maneuvers essential for predation and escape.[55] Biomechanical studies in working and agility dogs demonstrate that intact dewclaws correlate with reduced injury risk and improved performance. For instance, a survey of agility dogs found that the absence of front dewclaws was a significant risk factor for digit injuries, suggesting that dewclaws help mitigate torque and stress on other toes during high-speed turns and landings, potentially leading to faster acceleration and lower joint strain compared to removed counterparts.[56] Their protective role in locomotion is underscored without themselves being highly prone to trauma. Comparatively, dewclaws are more critical for locomotion in agile carnivorans like dogs and cats, where rapid directional changes demand precise stability, than in ungulates, which rely primarily on their main digits for weight-bearing during steady gaits. In hoofed species such as cattle and reindeer, dewclaws offer supplementary support on steep or deep terrain by preventing over-extension of the hoof and enhancing traction in soft or uneven ground, but they contribute less to overall speed or agility in flat or lumbering movement.[4][49]Sensory and Support Functions

In carnivorans such as dogs and cats, dewclaws contribute to tactile sensing through innervation similar to other digits, enabling detection of environmental textures during activities like grasping prey or navigating surfaces.[3][57] For instance, in cats, the dewclaw's role in holding objects allows for feedback on surface irregularities via mechanoreceptors similar to those in other digits.[58] In ungulates like cattle and sheep, dewclaws provide static support by distributing weight on soft or steep terrain, such as mud or inclines, where they contact the ground to enhance stability and prevent slippage of the primary hooves.[4] Intact dewclaws improve balance in these conditions, reducing the risk of falls. Dewclaws also serve as a buffer for leg joints, absorbing minor stresses during periods of rest or slow ambulation, thereby protecting associated ligaments and reducing torque on the carpus or pastern.[59] In dogs, this stabilization is evidenced by veterinary analyses showing that dewclaw removal increases susceptibility to joint strains in low-speed scenarios.[60] Although often considered vestigial, these structures retain practical utility in passive support roles across species.[4] In birds and reptiles, dewclaws or analogous rudimentary digits may assist in perching or gripping during minimal locomotion, though their roles are less pronounced compared to mammals.[4]Removal and Management

Surgical Removal in Dogs

Surgical removal of dewclaws in dogs is typically performed on neonatal puppies to minimize trauma and facilitate rapid healing. The preferred timing is between 3 and 5 days of age, when the dewclaw has minimal bony attachment and the procedure can be done with limited discomfort.[61][62] At this stage, the loose attachment of the dewclaw to the leg allows for straightforward excision without deep dissection.[61] The procedure involves surgical scrubbing of the area followed by local infiltration of the base with lidocaine (0.5-0.75 mg/kg without epinephrine) for anesthesia. The dewclaw is then excised as close to the base as possible using a scalpel or surgical clippers, with any bleeding vessels ligated using absorbable suture material for hemostasis. General anesthesia is generally not required for neonates, though sedation may be used if needed; in older puppies or adults, general anesthesia is standard to ensure safety and pain control.[3][63][62] Post-operative care emphasizes wound monitoring and prevention of complications. The surgical site is often bandaged lightly to protect it, and owners are advised to inspect daily for signs of redness, swelling, discharge, or pain, cleaning gently with saline if directed by the veterinarian. Pain management typically involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as carprofen at 2-4 mg/kg every 12-24 hours for 3-5 days, particularly in older animals. Infection risks exist due to bacterial entry at the site, but complications like dehiscence or abscess formation are uncommon when performed by experienced practitioners.[62][64][62] Breed considerations influence the routine application of dewclaw removal. It is commonly performed in working and hunting breeds, such as retrievers and pointers, to reduce the risk of the dewclaw snagging during activity, though some breed standards, like those for Great Pyrenees or Briards, explicitly prohibit or discourage removal to preserve natural anatomy.[65][66] This practice originated in the 19th century amid selective breeding for working dogs, where removal was adopted to prevent injuries and enhance aesthetics in emerging breed standards.[65]Controversies and Welfare Implications

The practice of dewclaw removal in dogs has sparked significant debate within veterinary and animal welfare communities, primarily due to its elective nature and potential impacts on canine health. Proponents argue that removal, particularly in working or active breeds, mitigates the risk of traumatic injuries, as loosely attached dewclaws can tear during rough terrain navigation or play, leading to painful wounds requiring veterinary intervention. A 2018 JAVMA survey of agility dogs found that among the 110 dogs with digit injuries that retained front dewclaws, 7.3% (8 dogs) had injuries specifically to the dewclaw, though overall digit trauma rates were higher in dogs without dewclaws, suggesting removal may not eliminate injury risks but could prevent specific complications in high-energy scenarios.[56] Opponents highlight the ethical concerns of performing surgery on healthy tissue, emphasizing acute postoperative pain and risks of complications such as infection or excessive bleeding, even when conducted neonatally. Long-term studies and clinical observations indicate that removal may alter biomechanics, contributing to minor gait instability and increased susceptibility to carpal arthritis due to lost stabilization during turns or torque. Veterinary reviews classify routine dewclaw removal as a medically unnecessary surgery, noting insufficient evidence that benefits outweigh these welfare costs for most dogs.[61] Regulatory frameworks reflect these tensions, with restrictions on non-therapeutic dewclaw removal in some European countries, such as Ireland, where it is prohibited except for medical reasons under strict animal welfare laws. In North America, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) lacks a specific policy on dewclaws but broadly discourages non-therapeutic alterations, recommending they be reserved for medical necessity to align with ethical standards. These restrictions underscore a global shift toward prioritizing natural anatomy unless health risks justify intervention.[67][68] Alternatives to surgical removal focus on preventive management to address injury concerns without compromising welfare. Regular nail trimming maintains dewclaw length and reduces snagging risks, while protective boots or wraps provide shielding for active dogs during fieldwork or exercise. Selective breeding for breeds with firmly attached, functional dewclaws—common in many European lines—offers a long-term solution, promoting genetic retention of natural traits that enhance stability without procedural intervention.[66][6]Evolutionary and Comparative Biology

Evolutionary Origins

The dewclaw traces its origins to the pentadactyl limb structure characteristic of early tetrapods, which emerged around 360 million years ago during the Devonian period and persisted in the basal synapsids—the ancestral lineage leading to mammals—dating back approximately 300 million years to the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods.[69] In these early synapsids, such as pelycosaurs like Dimetrodon, all five digits were fully functional, supporting sprawling locomotion and adaptation to terrestrial environments from amphibious ancestors.[70] As synapsids evolved toward more advanced forms, including therapsids in the Permian and Triassic, the limb retained this five-digited configuration, though phalangeal counts in digits 3, 4, and 5 began to reduce slightly to enhance mobility on land.[69] Fossil evidence underscores these origins, with trackways and skeletal remains from early synapsids showing complete pentadactyly, including precursors to dewclaws as the lateral (digits 1 and 5) or medial elements of the autopodium.[71] In non-mammalian contexts, theropod dinosaurs preserved a reversed hallux (digit 1) as a grasping structure, representing a parallel retention of an elevated digit homologous to aspects of the mammalian dewclaw, though mammalian evolution diverged post-Cretaceous around 66 million years ago following the extinction of dinosaurs.[72] Major transitions occurred during the Cenozoic radiation of mammals, where digit reduction became pronounced in ungulate lineages; for instance, perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates) evolved from five-toed ancestors to three-toed forms by the Eocene, with further loss to a single functional digit in equids like horses, while retaining vestigial lateral digits as dewclaws.[73] In contrast, carnivorans maintained the first digit (dewclaw) in a more prominent position, likely due to selective pressures favoring its role in ancestral predatory behaviors during the Paleogene diversification of placental mammals.[4] Genetic drivers of dewclaw vestigiality involve mutations altering limb patterning genes, particularly those regulating the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) and apoptosis during embryogenesis. Studies on artiodactyls like pigs reveal that suppression of digits 1, 2, and 5 stems from modified expression of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) and HoxD cluster genes, leading to expanded interdigital cell death and reduced chondrogenesis in early limb bud stages.[74] In equids, similar post-patterning mechanisms, including upregulated apoptosis via BMP signaling, drove progressive digit loss from Eocene ancestors to modern forms, transforming functional digits into non-weight-bearing dewclaws.[75] Transcriptomic analyses across mammals confirm that regulatory divergences in these developmental genes underpin the macroevolutionary shifts toward digit reduction, providing a molecular basis for the vestigial state observed today.[76]Variations Across Mammals

In primates, the first digit, or pollex (thumb), exhibits significant variation, with reduction observed in several taxa to facilitate specialized locomotion or feeding. For instance, in colobine monkeys such as Colobus and African and Asian colobines, the thumb is markedly reduced in size relative to other digits, aiding in suspensory behaviors like branch hanging, while opposability is retained for limited grasping functions.[77] In more extreme cases, New World primates like spider monkeys (Ateles) and woolly spider monkeys (Brachyteles) have lost the external thumb entirely, relying instead on hook-like grips formed by the remaining four digits for arboreal travel.[77] Humans, by contrast, lack a vestigial dewclaw equivalent, with the fully integrated opposable thumb supporting precision manipulation.[78] Beyond primates, dewclaw-like structures vary widely across other mammalian orders, often reflecting locomotor adaptations. In the carnivoran family Ursidae (bears), the first digit on the forepaw is fully developed and functional, serving as a gripping tool for climbing, digging, and prey manipulation, without vestigial reduction.[79] In cetaceans, such as dolphins and whales, external digits are absent due to the complete reduction of hindlimbs into vestigial internal elements during aquatic adaptation; foreflippers retain embedded phalanges with hyperphalangy (extra segments), but no distinct dewclaw forms, as the entire appendage functions as a streamlined paddle.[80] Rodents typically possess a small but functional first digit (D1 or thumb equivalent) on the forepaw, characterized by a specialized thumbnail that enhances manual dexterity for food handling and nest building, rather than true vestigiality.[81] These variations illustrate broader patterns of adaptive radiation in mammalian digit evolution, where dewclaw retention or modification correlates with lifestyle. Cursorial (running) mammals, such as many ungulates and some carnivorans, often preserve reduced but supportive dewclaws for traction on uneven terrain, preventing slippage during high-speed movement.[75] In contrast, fossorial (burrowing) and fully aquatic species, including moles and cetaceans, show frequent loss or extreme reduction of digits, including dewclaw analogues, to streamline bodies for digging or swimming efficiency.[75] Comparative anatomy surveys indicate that vestigial or modified dewclaw forms occur in a majority of mammalian orders, though precise species-level prevalence varies by ecological niche.[82]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/317347985_Anatomy_and_imaging_features_of_the_dew_claws_of_the_water_buffalo_and_cow