Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Linked list

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2012) |

In computer science, a linked list is a linear collection of data elements whose order is not given by their physical placement in memory. Instead, each element points to the next. It is a data structure consisting of a collection of nodes which together represent a sequence. In its most basic form, each node contains data, and a reference (in other words, a link) to the next node in the sequence. This structure allows for efficient insertion or removal of elements from any position in the sequence during iteration. More complex variants add additional links, allowing more efficient insertion or removal of nodes at arbitrary positions. A drawback of linked lists is that data access time is linear in respect to the number of nodes in the list. Because nodes are serially linked, accessing any node requires that the prior node be accessed beforehand (which introduces difficulties in pipelining). Faster access, such as random access, is not feasible. Arrays have better cache locality compared to linked lists.

Linked lists are among the simplest and most common data structures. They can be used to implement several other common abstract data types, including lists, stacks, queues, associative arrays, and S-expressions, though it is not uncommon to implement those data structures directly without using a linked list as the basis.

The principal benefit of a linked list over a conventional array is that the list elements can be easily inserted or removed without reallocation or reorganization of the entire structure because the data items do not need to be stored contiguously in memory or on disk, while restructuring an array at run-time is a much more expensive operation. Linked lists allow insertion and removal of nodes at any point in the list, and allow doing so with a constant number of operations by keeping the link previous to the link being added or removed in memory during list traversal.

On the other hand, since simple linked lists by themselves do not allow random access to the data or any form of efficient indexing, many basic operations—such as obtaining the last node of the list, finding a node that contains a given datum, or locating the place where a new node should be inserted—may require iterating through most or all of the list elements.

History

[edit]Linked lists were developed in 1955–1956, by Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw and Herbert A. Simon at RAND Corporation and Carnegie Mellon University as the primary data structure for their Information Processing Language (IPL). IPL was used by the authors to develop several early artificial intelligence programs, including the Logic Theory Machine, the General Problem Solver, and a computer chess program. Reports on their work appeared in IRE Transactions on Information Theory in 1956, and several conference proceedings from 1957 to 1959, including Proceedings of the Western Joint Computer Conference in 1957 and 1958, and Information Processing (Proceedings of the first UNESCO International Conference on Information Processing) in 1959. The now-classic diagram consisting of blocks representing list nodes with arrows pointing to successive list nodes appears in "Programming the Logic Theory Machine" by Newell and Shaw in Proc. WJCC, February 1957. Newell and Simon were recognized with the ACM Turing Award in 1975 for having "made basic contributions to artificial intelligence, the psychology of human cognition, and list processing". The problem of machine translation for natural language processing led Victor Yngve at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to use linked lists as data structures in his COMIT programming language for computer research in the field of linguistics. A report on this language entitled "A programming language for mechanical translation" appeared in Mechanical Translation in 1958.[citation needed]

Another early appearance of linked lists was by Hans Peter Luhn who wrote an internal IBM memorandum in January 1953 that suggested the use of linked lists in chained hash tables.[1]

LISP, standing for list processor, was created by John McCarthy in 1958 while he was at MIT and in 1960 he published its design in a paper in the Communications of the ACM, entitled "Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I". One of LISP's major data structures is the linked list.

By the early 1960s, the utility of both linked lists and languages which use these structures as their primary data representation was well established. Bert Green of the MIT Lincoln Laboratory published a review article entitled "Computer languages for symbol manipulation" in IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics in March 1961 which summarized the advantages of the linked list approach. A later review article, "A Comparison of list-processing computer languages" by Bobrow and Raphael, appeared in Communications of the ACM in April 1964.

Several operating systems developed by Technical Systems Consultants (originally of West Lafayette Indiana, and later of Chapel Hill, North Carolina) used singly linked lists as file structures. A directory entry pointed to the first sector of a file, and succeeding portions of the file were located by traversing pointers. Systems using this technique included Flex (for the Motorola 6800 CPU), mini-Flex (same CPU), and Flex9 (for the Motorola 6809 CPU). A variant developed by TSC for and marketed by Smoke Signal Broadcasting in California, used doubly linked lists in the same manner.

The TSS/360 operating system, developed by IBM for the System 360/370 machines, used a double linked list for their file system catalog. The directory structure was similar to Unix, where a directory could contain files and other directories and extend to any depth.

Basic concepts and nomenclature

[edit]Each record of a linked list is often called an 'element' or 'node'.

The field of each node that contains the address of the next node is usually called the 'next link' or 'next pointer'. The remaining fields are known as the 'data', 'information', 'value', 'cargo', or 'payload' fields.

The 'head' of a list is its first node. The 'tail' of a list may refer either to the rest of the list after the head, or to the last node in the list. In Lisp and some derived languages, the next node may be called the 'cdr' (pronounced /'kʊd.əɹ/) of the list, while the payload of the head node may be called the 'car'.

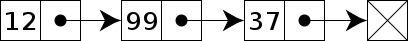

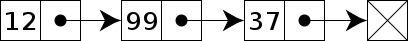

Singly linked list

[edit]Singly linked lists contain nodes which have a 'value' field as well as 'next' field, which points to the next node in line of nodes. Operations that can be performed on singly linked lists include insertion, deletion and traversal.

The following C language code demonstrates how to add a new node with the "value" to the end of a singly linked list:

#include <stdlib.h>

// Each node in a linked list is a structure. The head node is the first node in the list.

typedef struct Node {

int value;

struct Node* next;

} Node;

Node* addNodeToTail(Node* head, int value) {

// declare Node pointer and initialize to point to the new Node (i.e., it will have the new Node's memory address) being added to the end of the list.

Node* temp = (Node*)malloc(sizeof *temp); /// 'malloc' in stdlib.

temp->value = value; // Add data to the value field of the new Node.

temp->next = nullptr; // initialize invalid links to nil.

if (!head) {

head = temp; // If the linked list is empty (i.e., the head node pointer is a null pointer), then have the head node pointer point to the new Node.

} else {

Node* p = head; // Assign the head node pointer to the Node pointer 'p'.

while (p->next) {

p = p->next; // Traverse the list until p is the last Node. The last Node always points to nullptr (NULL).

}

p->next = temp; // Make the previously last Node point to the new Node.

}

return head; // Return the head node pointer.

}

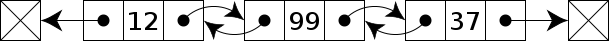

Doubly linked list

[edit]In a 'doubly linked list', each node contains, besides the next-node link, a second link field pointing to the 'previous' node in the sequence. The two links may be called 'forward('s') and 'backwards', or 'next' and 'prev'('previous').

A technique known as XOR-linking allows a doubly linked list to be implemented using a single link field in each node. However, this technique requires the ability to do bit operations on addresses, and therefore may not be available in some high-level languages.

Many modern operating systems use doubly linked lists to maintain references to active processes, threads, and other dynamic objects.[2] A common strategy for rootkits to evade detection is to unlink themselves from these lists.[3]

Multiply linked list

[edit]In a 'multiply linked list', each node contains two or more link fields, each field being used to connect the same set of data arranged in a different order (e.g., by name, by department, by date of birth, etc.). While a doubly linked list can be seen as a special case of multiply linked list, the fact that the two and more orders are opposite to each other leads to simpler and more efficient algorithms, so they are usually treated as a separate case.

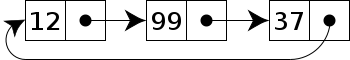

Circular linked list

[edit]In the last node of a linked list, the link field often contains a null reference, a special value is used to indicate the lack of further nodes. A less common convention is to make it point to the first node of the list; in that case, the list is said to be 'circular' or 'circularly linked'; otherwise, it is said to be 'open' or 'linear'. It is a list where the last node pointer points to the first node (i.e., the "next link" pointer of the last node has the memory address of the first node).

In the case of a circular doubly linked list, the first node also points to the last node of the list.

Sentinel nodes

[edit]In some implementations an extra 'sentinel' or 'dummy' node may be added before the first data record or after the last one. This convention simplifies and accelerates some list-handling algorithms, by ensuring that all links can be safely dereferenced and that every list (even one that contains no data elements) always has a "first" and "last" node.

Empty lists

[edit]An empty list is a list that contains no data records. This is usually the same as saying that it has zero nodes. If sentinel nodes are being used, the list is usually said to be empty when it has only sentinel nodes.

Hash linking

[edit]The link fields need not be physically part of the nodes. If the data records are stored in an array and referenced by their indices, the link field may be stored in a separate array with the same indices as the data records.

List handles

[edit]Since a reference to the first node gives access to the whole list, that reference is often called the 'address', 'pointer', or 'handle' of the list. Algorithms that manipulate linked lists usually get such handles to the input lists and return the handles to the resulting lists. In fact, in the context of such algorithms, the word "list" often means "list handle". In some situations, however, it may be convenient to refer to a list by a handle that consists of two links, pointing to its first and last nodes.

Combining alternatives

[edit]The alternatives listed above may be arbitrarily combined in almost every way, so one may have circular doubly linked lists without sentinels, circular singly linked lists with sentinels, etc.

Tradeoffs

[edit]As with most choices in computer programming and design, no method is well suited to all circumstances. A linked list data structure might work well in one case, but cause problems in another. This is a list of some of the common tradeoffs involving linked list structures.

Linked lists vs. dynamic arrays

[edit]| Peek (index) |

Mutate (insert or delete) at … | Excess space, average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning | End | Middle | |||

| Linked list | Θ(n) | Θ(1) | Θ(1), known end element; Θ(n), unknown end element |

Θ(n) | Θ(n) |

| Array | Θ(1) | — | — | — | 0 |

| Dynamic array | Θ(1) | Θ(n) | Θ(1) amortized | Θ(n) | Θ(n)[4] |

| Balanced tree | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(n) |

| Random-access list | Θ(log n)[5] | Θ(1) | —[5] | —[5] | Θ(n) |

| Hashed array tree | Θ(1) | Θ(n) | Θ(1) amortized | Θ(n) | Θ(√n) |

A dynamic array is a data structure that allocates all elements contiguously in memory, and keeps a count of the current number of elements. If the space reserved for the dynamic array is exceeded, it is reallocated and (possibly) copied, which is an expensive operation.

Linked lists have several advantages over dynamic arrays. Insertion or deletion of an element at a specific point of a list, assuming that a pointer is indexed to the node (before the one to be removed, or before the insertion point) already, is a constant-time operation (otherwise without this reference it is O(n)), whereas insertion in a dynamic array at random locations will require moving half of the elements on average, and all the elements in the worst case. While one can "delete" an element from an array in constant time by somehow marking its slot as "vacant", this causes fragmentation that impedes the performance of iteration.

Moreover, arbitrarily many elements may be inserted into a linked list, limited only by the total memory available; while a dynamic array will eventually fill up its underlying array data structure and will have to reallocate—an expensive operation, one that may not even be possible if memory is fragmented, although the cost of reallocation can be averaged over insertions, and the cost of an insertion due to reallocation would still be amortized O(1). This helps with appending elements at the array's end, but inserting into (or removing from) middle positions still carries prohibitive costs due to data moving to maintain contiguity. An array from which many elements are removed may also have to be resized in order to avoid wasting too much space.

On the other hand, dynamic arrays (as well as fixed-size array data structures) allow constant-time random access, while linked lists allow only sequential access to elements. Singly linked lists, in fact, can be easily traversed in only one direction. This makes linked lists unsuitable for applications where it's useful to look up an element by its index quickly, such as heapsort. Sequential access on arrays and dynamic arrays is also faster than on linked lists on many machines, because they have optimal locality of reference and thus make good use of data caching.

Another disadvantage of linked lists is the extra storage needed for references, which often makes them impractical for lists of small data items such as characters or Boolean values, because the storage overhead for the links may exceed by a factor of two or more the size of the data. In contrast, a dynamic array requires only the space for the data itself (and a very small amount of control data).[note 1] It can also be slow, and with a naïve allocator, wasteful, to allocate memory separately for each new element, a problem generally solved using memory pools.

Some hybrid solutions try to combine the advantages of the two representations. Unrolled linked lists store several elements in each list node, increasing cache performance while decreasing memory overhead for references. CDR coding does both these as well, by replacing references with the actual data referenced, which extends off the end of the referencing record.

A good example that highlights the pros and cons of using dynamic arrays vs. linked lists is by implementing a program that resolves the Josephus problem. The Josephus problem is an election method that works by having a group of people stand in a circle. Starting at a predetermined person, one may count around the circle n times. Once the nth person is reached, one should remove them from the circle and have the members close the circle. The process is repeated until only one person is left. That person wins the election. This shows the strengths and weaknesses of a linked list vs. a dynamic array, because if the people are viewed as connected nodes in a circular linked list, then it shows how easily the linked list is able to delete nodes (as it only has to rearrange the links to the different nodes). However, the linked list will be poor at finding the next person to remove and will need to search through the list until it finds that person. A dynamic array, on the other hand, will be poor at deleting nodes (or elements) as it cannot remove one node without individually shifting all the elements up the list by one. However, it is exceptionally easy to find the nth person in the circle by directly referencing them by their position in the array.

The list ranking problem concerns the efficient conversion of a linked list representation into an array. Although trivial for a conventional computer, solving this problem by a parallel algorithm is complicated and has been the subject of much research.

A balanced tree has similar memory access patterns and space overhead to a linked list while permitting much more efficient indexing, taking O(log n) time instead of O(n) for a random access. However, insertion and deletion operations are more expensive due to the overhead of tree manipulations to maintain balance. Schemes exist for trees to automatically maintain themselves in a balanced state: AVL trees or red–black trees.

Singly linked linear lists vs. other lists

[edit]While doubly linked and circular lists have advantages over singly linked linear lists, linear lists offer some advantages that make them preferable in some situations.

A singly linked linear list is a recursive data structure, because it contains a pointer to a smaller object of the same type. For that reason, many operations on singly linked linear lists (such as merging two lists, or enumerating the elements in reverse order) often have very simple recursive algorithms, much simpler than any solution using iterative commands. While those recursive solutions can be adapted for doubly linked and circularly linked lists, the procedures generally need extra arguments and more complicated base cases.

Linear singly linked lists also allow tail-sharing, the use of a common final portion of sub-list as the terminal portion of two different lists. In particular, if a new node is added at the beginning of a list, the former list remains available as the tail of the new one—a simple example of a persistent data structure. Again, this is not true with the other variants: a node may never belong to two different circular or doubly linked lists.

In particular, end-sentinel nodes can be shared among singly linked non-circular lists. The same end-sentinel node may be used for every such list. In Lisp, for example, every proper list ends with a link to a special node, denoted by nil or ().

The advantages of the fancy variants are often limited to the complexity of the algorithms, not in their efficiency. A circular list, in particular, can usually be emulated by a linear list together with two variables that point to the first and last nodes, at no extra cost.

Doubly linked vs. singly linked

[edit]Double-linked lists require more space per node (unless one uses XOR-linking), and their elementary operations are more expensive; but they are often easier to manipulate because they allow fast and easy sequential access to the list in both directions. In a doubly linked list, one can insert or delete a node in a constant number of operations given only that node's address. To do the same in a singly linked list, one must have the address of the pointer to that node, which is either the handle for the whole list (in case of the first node) or the link field in the previous node. Some algorithms require access in both directions. On the other hand, doubly linked lists do not allow tail-sharing and cannot be used as persistent data structures.

Circularly linked vs. linearly linked

[edit]A circularly linked list may be a natural option to represent arrays that are naturally circular, e.g. the corners of a polygon, a pool of buffers that are used and released in FIFO ("first in, first out") order, or a set of processes that should be time-shared in round-robin order. In these applications, a pointer to any node serves as a handle to the whole list.

With a circular list, a pointer to the last node gives easy access also to the first node, by following one link. Thus, in applications that require access to both ends of the list (e.g., in the implementation of a queue), a circular structure allows one to handle the structure by a single pointer, instead of two.

A circular list can be split into two circular lists, in constant time, by giving the addresses of the last node of each piece. The operation consists in swapping the contents of the link fields of those two nodes. Applying the same operation to any two nodes in two distinct lists joins the two list into one. This property greatly simplifies some algorithms and data structures, such as the quad-edge and face-edge.

The simplest representation for an empty circular list (when such a thing makes sense) is a null pointer, indicating that the list has no nodes. Without this choice, many algorithms have to test for this special case, and handle it separately. By contrast, the use of null to denote an empty linear list is more natural and often creates fewer special cases.

For some applications, it can be useful to use singly linked lists that can vary between being circular and being linear, or even circular with a linear initial segment. Algorithms for searching or otherwise operating on these have to take precautions to avoid accidentally entering an endless loop. One well-known method is to have a second pointer walking the list at half or double the speed, and if both pointers meet at the same node, a cycle has been found.

Using sentinel nodes

[edit]Sentinel node may simplify certain list operations, by ensuring that the next or previous nodes exist for every element, and that even empty lists have at least one node. One may also use a sentinel node at the end of the list, with an appropriate data field, to eliminate some end-of-list tests. For example, when scanning the list looking for a node with a given value x, setting the sentinel's data field to x makes it unnecessary to test for end-of-list inside the loop. Another example is the merging two sorted lists: if their sentinels have data fields set to +∞, the choice of the next output node does not need special handling for empty lists.

However, sentinel nodes use up extra space (especially in applications that use many short lists), and they may complicate other operations (such as the creation of a new empty list).

However, if the circular list is used merely to simulate a linear list, one may avoid some of this complexity by adding a single sentinel node to every list, between the last and the first data nodes. With this convention, an empty list consists of the sentinel node alone, pointing to itself via the next-node link. The list handle should then be a pointer to the last data node, before the sentinel, if the list is not empty; or to the sentinel itself, if the list is empty.

The same trick can be used to simplify the handling of a doubly linked linear list, by turning it into a circular doubly linked list with a single sentinel node. However, in this case, the handle should be a single pointer to the dummy node itself.[6]

Linked list operations

[edit]When manipulating linked lists in-place, care must be taken to not use values that have been invalidated in previous assignments. This makes algorithms for inserting or deleting linked list nodes somewhat subtle. This section gives pseudocode for adding or removing nodes from singly, doubly, and circularly linked lists in-place. Throughout, null is used to refer to an end-of-list marker or sentinel, which may be implemented in a number of ways.

Linearly linked lists

[edit]Singly linked lists

[edit]The node data structure will have two fields. There is also a variable, firstNode which always points to the first node in the list, or is null for an empty list.

record Node

{

data; // The data being stored in the node

Node next // A reference[2] to the next node, null for last node

}

record List

{

Node firstNode // points to first node of list; null for empty list

}

Traversal of a singly linked list is simple, beginning at the first node and following each next link until reaching the end:

node := list.firstNode

while node not null

(do something with node.data)

node := node.next

The following code inserts a node after an existing node in a singly linked list. The diagram shows how it works. Inserting a node before an existing one cannot be done directly; instead, one must keep track of the previous node and insert a node after it.

function insertAfter(Node node, Node newNode) // insert newNode after node

newNode.next := node.next

node.next := newNode

Inserting at the beginning of the list requires a separate function. This requires updating firstNode.

function insertBeginning(List list, Node newNode) // insert node before current first node

newNode.next := list.firstNode

list.firstNode := newNode

Similarly, there are functions for removing the node after a given node, and for removing a node from the beginning of the list. The diagram demonstrates the former. To find and remove a particular node, one must again keep track of the previous element.

function removeAfter(Node node) // remove node past this one

obsoleteNode := node.next

node.next := node.next.next

destroy obsoleteNode

function removeBeginning(List list) // remove first node

obsoleteNode := list.firstNode

list.firstNode := list.firstNode.next // point past deleted node

destroy obsoleteNode

Notice that removeBeginning() sets list.firstNode to null when removing the last node in the list.

Since it is not possible to iterate backwards, efficient insertBefore or removeBefore operations are not possible. Inserting to a list before a specific node requires traversing the list, which would have a worst case running time of O(n).

Appending one linked list to another can be inefficient unless a reference to the tail is kept as part of the List structure, because it is needed to traverse the entire first list in order to find the tail, and then append the second list to this. Thus, if two linearly linked lists are each of length , list appending has asymptotic time complexity of . In the Lisp family of languages, list appending is provided by the append procedure.

Many of the special cases of linked list operations can be eliminated by including a dummy element at the front of the list. This ensures that there are no special cases for the beginning of the list and renders both insertBeginning() and removeBeginning() unnecessary, i.e., every element or node is next to another node (even the first node is next to the dummy node). In this case, the first useful data in the list will be found at list.firstNode.next.

Circularly linked list

[edit]In a circularly linked list, all nodes are linked in a continuous circle, without using null. For lists with a front and a back (such as a queue), one stores a reference to the last node in the list. The next node after the last node is the first node. Elements can be added to the back of the list and removed from the front in constant time.

Circularly linked lists can be either singly or doubly linked.

Both types of circularly linked lists benefit from the ability to traverse the full list beginning at any given node. This often allows us to avoid storing firstNode and lastNode, although if the list may be empty, there needs to be a special representation for the empty list, such as a lastNode variable which points to some node in the list or is null if it is empty; it uses such a lastNode here. This representation significantly simplifies adding and removing nodes with a non-empty list, but empty lists are then a special case.

Algorithms

[edit]Assuming that someNode is some node in a non-empty circular singly linked list, this code iterates through that list starting with someNode:

function iterate(someNode)

if someNode ≠ null

node := someNode

do

do something with node.value

node := node.next

while node ≠ someNode

Notice that the test "while node ≠ someNode" must be at the end of the loop. If the test was moved to the beginning of the loop, the procedure would fail whenever the list had only one node.

This function inserts a node "newNode" into a circular linked list after a given node "node". If "node" is null, it assumes that the list is empty.

function insertAfter(Node node, Node newNode)

if node = null // assume list is empty

newNode.next := newNode

else

newNode.next := node.next

node.next := newNode

update lastNode variable if necessary

Suppose that "L" is a variable pointing to the last node of a circular linked list (or null if the list is empty). To append "newNode" to the end of the list, one may do

insertAfter(L, newNode) L := newNode

To insert "newNode" at the beginning of the list, one may do

insertAfter(L, newNode)

if L = null

L := newNode

This function inserts a value "newVal" before a given node "node" in O(1) time. A new node has been created between "node" and the next node, then puts the value of "node" into that new node, and puts "newVal" in "node". Thus, a singly linked circularly linked list with only a firstNode variable can both insert to the front and back in O(1) time.

function insertBefore(Node node, newVal)

if node = null // assume list is empty

newNode := new Node(data:=newVal, next:=newNode)

else

newNode := new Node(data:=node.data, next:=node.next)

node.data := newVal

node.next := newNode

update firstNode variable if necessary

This function removes a non-null node from a list of size greater than 1 in O(1) time. It copies data from the next node into the node, and then sets the node's next pointer to skip over the next node.

function remove(Node node)

if node ≠ null and size of list > 1

removedData := node.data

node.data := node.next.data

node.next = node.next.next

return removedData

Linked lists using arrays of nodes

[edit]Languages that do not support any type of reference can still create links by replacing pointers with array indices. The approach is to keep an array of records, where each record has integer fields indicating the index of the next (and possibly previous) node in the array. Not all nodes in the array need be used. If records are also not supported, parallel arrays can often be used instead.

As an example, consider the following linked list record that uses arrays instead of pointers:

record Entry {

integer next; // index of next entry in array

integer prev; // previous entry (if double-linked)

string name;

real balance;

}

A linked list can be built by creating an array of these structures, and an integer variable to store the index of the first element.

integer listHead Entry Records[1000]

Links between elements are formed by placing the array index of the next (or previous) cell into the Next or Prev field within a given element. For example:

| Index | Next | Prev | Name | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 4 | Jones, John | 123.45 |

| 1 | −1 | 0 | Smith, Joseph | 234.56 |

| 2 (listHead) | 4 | −1 | Adams, Adam | 0.00 |

| 3 | Ignore, Ignatius | 999.99 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 2 | Another, Anita | 876.54 |

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 |

In the above example, ListHead would be set to 2, the location of the first entry in the list. Notice that entry 3 and 5 through 7 are not part of the list. These cells are available for any additions to the list. By creating a ListFree integer variable, a free list could be created to keep track of what cells are available. If all entries are in use, the size of the array would have to be increased or some elements would have to be deleted before new entries could be stored in the list.

The following code would traverse the list and display names and account balance:

i := listHead

while i ≥ 0 // loop through the list

print i, Records[i].name, Records[i].balance // print entry

i := Records[i].next

When faced with a choice, the advantages of this approach include:

- The linked list is relocatable, meaning it can be moved about in memory at will, and it can also be quickly and directly serialized for storage on disk or transfer over a network.

- Especially for a small list, array indexes can occupy significantly less space than a full pointer on many architectures.

- Locality of reference can be improved by keeping the nodes together in memory and by periodically rearranging them, although this can also be done in a general store.

- Naïve dynamic memory allocators can produce an excessive amount of overhead storage for each node allocated; almost no allocation overhead is incurred per node in this approach.

- Seizing an entry from a pre-allocated array is faster than using dynamic memory allocation for each node, since dynamic memory allocation typically requires a search for a free memory block of the desired size.

This approach has one main disadvantage, however: it creates and manages a private memory space for its nodes. This leads to the following issues:

- It increases complexity of the implementation.

- Growing a large array when it is full may be difficult or impossible, whereas finding space for a new linked list node in a large, general memory pool may be easier.

- Adding elements to a dynamic array will occasionally (when it is full) unexpectedly take linear (O(n)) instead of constant time (although it is still an amortized constant).

- Using a general memory pool leaves more memory for other data if the list is smaller than expected or if many nodes are freed.

For these reasons, this approach is mainly used for languages that do not support dynamic memory allocation. These disadvantages are also mitigated if the maximum size of the list is known at the time the array is created.

Language support

[edit]Many programming languages such as Lisp and Scheme have singly linked lists built in. In many functional languages, these lists are constructed from nodes, each called a cons or cons cell. The cons has two fields: the car, a reference to the data for that node, and the cdr, a reference to the next node. Although cons cells can be used to build other data structures, this is their primary purpose.

In languages that support abstract data types or templates, linked list ADTs or templates are available for building linked lists. In other languages, linked lists are typically built using references together with records.

Internal and external storage

[edit]When constructing a linked list, one is faced with the choice of whether to store the data of the list directly in the linked list nodes, called internal storage, or merely to store a reference to the data, called external storage. Internal storage has the advantage of making access to the data more efficient, requiring less storage overall, having better locality of reference, and simplifying memory management for the list (its data is allocated and deallocated at the same time as the list nodes).

External storage, on the other hand, has the advantage of being more generic, in that the same data structure and machine code can be used for a linked list no matter what the size of the data is. It also makes it easy to place the same data in multiple linked lists. Although with internal storage the same data can be placed in multiple lists by including multiple next references in the node data structure, it would then be necessary to create separate routines to add or delete cells based on each field. It is possible to create additional linked lists of elements that use internal storage by using external storage, and having the cells of the additional linked lists store references to the nodes of the linked list containing the data.

In general, if a set of data structures needs to be included in linked lists, external storage is the best approach. If a set of data structures need to be included in only one linked list, then internal storage is slightly better, unless a generic linked list package using external storage is available. Likewise, if different sets of data that can be stored in the same data structure are to be included in a single linked list, then internal storage would be fine.

Another approach that can be used with some languages involves having different data structures, but all have the initial fields, including the next (and prev if double linked list) references in the same location. After defining separate structures for each type of data, a generic structure can be defined that contains the minimum amount of data shared by all the other structures and contained at the top (beginning) of the structures. Then generic routines can be created that use the minimal structure to perform linked list type operations, but separate routines can then handle the specific data. This approach is often used in message parsing routines, where several types of messages are received, but all start with the same set of fields, usually including a field for message type. The generic routines are used to add new messages to a queue when they are received, and remove them from the queue in order to process the message. The message type field is then used to call the correct routine to process the specific type of message.

Example of internal and external storage

[edit]To create a linked list of families and their members, using internal storage, the structure might look like the following:

record member { // member of a family

member next;

string firstName;

integer age;

}

record family { // the family itself

family next;

string lastName;

string address;

member members // head of list of members of this family

}

To print a complete list of families and their members using internal storage, write:

aFamily := Families // start at head of families list

while aFamily ≠ null // loop through list of families

print information about family

aMember := aFamily.members // get head of list of this family's members

while aMember ≠ null // loop through list of members

print information about member

aMember := aMember.next

aFamily := aFamily.next

Using external storage, the following structures can be created:

record node { // generic link structure

node next;

pointer data // generic pointer for data at node

}

record member { // structure for family member

string firstName;

integer age

}

record family { // structure for family

string lastName;

string address;

node members // head of list of members of this family

}

To print a complete list of families and their members using external storage, write:

famNode := Families // start at head of families list

while famNode ≠ null // loop through list of families

aFamily := (family) famNode.data // extract family from node

print information about family

memNode := aFamily.members // get list of family members

while memNode ≠ null // loop through list of members

aMember := (member)memNode.data // extract member from node

print information about member

memNode := memNode.next

famNode := famNode.next

Notice that when using external storage, an extra step is needed to extract the record from the node and cast it into the proper data type. This is because both the list of families and the list of members within the family are stored in two linked lists using the same data structure (node), and this language does not have parametric types.

As long as the number of families that a member can belong to is known at compile time, internal storage works fine. If, however, a member needed to be included in an arbitrary number of families, with the specific number known only at run time, external storage would be necessary.

Speeding up search

[edit]Finding a specific element in a linked list, even if it is sorted, normally requires O(n) time (linear search). This is one of the primary disadvantages of linked lists over other data structures. In addition to the variants discussed above, below are two simple ways to improve search time.

In an unordered list, one simple heuristic for decreasing average search time is the move-to-front heuristic, which simply moves an element to the beginning of the list once it is found. This scheme, handy for creating simple caches, ensures that the most recently used items are also the quickest to find again.

Another common approach is to "index" a linked list using a more efficient external data structure. For example, one can build a red–black tree or hash table whose elements are references to the linked list nodes. Multiple such indexes can be built on a single list. The disadvantage is that these indexes may need to be updated each time a node is added or removed (or at least, before that index is used again).

Random-access lists

[edit]A random-access list is a list with support for fast random access to read or modify any element in the list.[7] One possible implementation is a skew binary random-access list using the skew binary number system, which involves a list of trees with special properties; this allows worst-case constant time head/cons operations, and worst-case logarithmic time random access to an element by index.[7] Random-access lists can be implemented as persistent data structures.[7]

Random-access lists can be viewed as immutable linked lists in that they likewise support the same O(1) head and tail operations.[7]

A simple extension to random-access lists is the min-list, which provides an additional operation that yields the minimum element in the entire list in constant time (without[clarification needed] mutation complexities).[7]

Related data structures

[edit]Both stacks and queues are often implemented using linked lists, and simply restrict the type of operations which are supported.

The skip list is a linked list augmented with layers of pointers for quickly jumping over large numbers of elements, and then descending to the next layer. This process continues down to the bottom layer, which is the actual list.

A binary tree can be seen as a type of linked list where the elements are themselves linked lists of the same nature. The result is that each node may include a reference to the first node of one or two other linked lists, which, together with their contents, form the subtrees below that node.

An unrolled linked list is a linked list in which each node contains an array of data values. This leads to improved cache performance, since more list elements are contiguous in memory, and reduced memory overhead, because less metadata needs to be stored for each element of the list.

A hash table may use linked lists to store the chains of items that hash to the same position in the hash table.

A heap shares some of the ordering properties of a linked list, but is almost always implemented using an array. Instead of references from node to node, the next and previous data indexes are calculated using the current data's index.

A self-organizing list rearranges its nodes based on some heuristic which reduces search times for data retrieval by keeping commonly accessed nodes at the head of the list.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The amount of control data required for a dynamic array is usually of the form , where is a per-array constant, is a per-dimension constant, and is the number of dimensions. and are typically on the order of 10 bytes.

References

[edit]- ^ Knuth, Donald (1998). The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 3: Sorting and Searching (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-201-89685-5.

- ^ a b "The NT Insider:Kernel-Mode Basics: Windows Linked Lists". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ^ Butler, Jamie; Hoglund, Greg. "VICE – Catch the hookers! (Plus new rootkit techniques)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-01. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ Brodnik, Andrej; Carlsson, Svante; Sedgewick, Robert; Munro, JI; Demaine, ED (1999), Resizable Arrays in Optimal Time and Space (Technical Report CS-99-09) (PDF), Department of Computer Science, University of Waterloo

- ^ a b c Chris Okasaki (1995). "Purely Functional Random-Access Lists". Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Functional Programming Languages and Computer Architecture: 86–95. doi:10.1145/224164.224187.

- ^ Ford, William; Topp, William (2002). Data Structures with C++ using STL (Second ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 466–467. ISBN 0-13-085850-1.

- ^ a b c d e Okasaki, Chris (1995). Purely Functional Random-Access Lists. ACM Press. pp. 86–95. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Further reading

[edit]- Juan, Angel (2006). "Ch20 –Data Structures; ID06 - PROGRAMMING with JAVA (slide part of the book 'Big Java', by CayS. Horstmann)" (PDF). p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-06. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- Black, Paul E. (2004-08-16). Pieterse, Vreda; Black, Paul E. (eds.). "linked list". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2004-12-14.

- Antonakos, James L.; Mansfield, Kenneth C. Jr. (1999). Practical Data Structures Using C/C++. Prentice-Hall. pp. 165–190. ISBN 0-13-280843-9.

- Collins, William J. (2005) [2002]. Data Structures and the Java Collections Framework. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 239–303. ISBN 0-07-282379-8.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2003). Introduction to Algorithms. MIT Press. pp. 205–213, 501–505. ISBN 0-262-03293-7.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). "10.2: Linked lists". Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press. pp. 204–209. ISBN 0-262-03293-7.

- Green, Bert F. Jr. (1961). "Computer Languages for Symbol Manipulation". IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics (2): 3–8. doi:10.1109/THFE2.1961.4503292.

- McCarthy, John (1960). "Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I". Communications of the ACM. 3 (4): 184. doi:10.1145/367177.367199. S2CID 1489409.

- Knuth, Donald (1997). "2.2.3-2.2.5". Fundamental Algorithms (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 254–298. ISBN 0-201-89683-4.

- Newell, Allen; Shaw, F. C. (1957). "Programming the Logic Theory Machine". Proceedings of the Western Joint Computer Conference: 230–240.

- Parlante, Nick (2001). "Linked list basics" (PDF). Stanford University. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- Sedgewick, Robert (1998). Algorithms in C. Addison Wesley. pp. 90–109. ISBN 0-201-31452-5.

- Shaffer, Clifford A. (1998). A Practical Introduction to Data Structures and Algorithm Analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 77–102. ISBN 0-13-660911-2.

- Wilkes, Maurice Vincent (1964). "An Experiment with a Self-compiling Compiler for a Simple List-Processing Language". Annual Review in Automatic Programming. 4 (1). Pergamon Press: 1. doi:10.1016/0066-4138(64)90013-8.

- Wilkes, Maurice Vincent (1964). "Lists and Why They are Useful". Proceeds of the ACM National Conference, Philadelphia 1964 (P–64). ACM: F1–1.

- Shanmugasundaram, Kulesh (2005-04-04). "Linux Kernel Linked List Explained". Archived from the original on 2009-09-25. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

External links

[edit]- Description from the Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures

- Introduction to Linked Lists, Stanford University Computer Science Library

- Linked List Problems, Stanford University Computer Science Library

- Open Data Structures - Chapter 3 - Linked Lists, Pat Morin

- Patent for the idea of having nodes which are in several linked lists simultaneously (note that this technique was widely used for many decades before the patent was granted)

- Implementation of a singly linked list in C

- Implementation of a singly linked list in C++

- Implementation of a doubly linked list in C

- Implementation of a doubly linked list in C++

Linked list

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Nomenclature

A linked list is a linear data structure consisting of a sequence of elements, known as nodes, where each node stores a data value and a reference to the next node in the sequence, allowing the elements to be connected dynamically without requiring contiguous memory allocation.[8][9] This structure relies on pointers or references—mechanisms in programming languages that store memory addresses to enable indirect access to data—as the fundamental building blocks for linking nodes.[10] In standard nomenclature, a "node" is the basic unit of a linked list, typically comprising two fields: a data field to hold the actual information (such as an integer, string, or object) and a next field serving as a pointer to the subsequent node.[8][9] The "head" refers to the pointer or reference to the first node in the list, providing the entry point for traversal; if the list is empty, the head points to null.[8] The "tail" denotes the last node, whose next pointer is set to null, marking the end of the sequence and preventing further traversal.[9] The null value acts as a terminator, indicating the absence of a subsequent node and distinguishing non-empty lists from the empty case.[8][9] A common way to represent a node in pseudocode, using a C-like structure, is as follows:struct Node {

int data; // Example data field (can be any type)

struct Node* next; // Pointer to the next node

};

struct Node {

int data; // Example data field (can be any type)

struct Node* next; // Pointer to the next node

};

Singly Linked List

A singly linked list is a type of linear data structure consisting of a sequence of nodes, where each node stores a data value and a single pointer (or reference) to the next node in the sequence. The list begins with a head pointer referencing the first node, and the final node contains a null pointer to signify the end of the list. This unidirectional linking allows traversal only in the forward direction, from head to tail.[11] In terms of memory layout, nodes in a singly linked list are typically allocated dynamically and stored in non-contiguous locations in memory, with pointers serving as the mechanism to connect them logically into a chain. This contrasts with contiguous structures like arrays, enabling efficient insertion and deletion without shifting elements, though it requires additional space for the pointers themselves.[12] The primary advantages of a singly linked list include its simplicity in implementation, as only one pointer per node is needed, leading to lower memory overhead—typically half the pointer storage compared to structures requiring bidirectional links. This makes it suitable for scenarios where forward-only access suffices and memory efficiency is prioritized. However, a key disadvantage is the inability to traverse backward efficiently; accessing a prior node requires restarting from the head and iterating forward, resulting in O(n time complexity in the worst case for such operations.[12][13] For illustration, consider pseudocode to create a singly linked list with three nodes containing values 1, 2, and 3:class Node {

int data;

Node next;

}

Node createList() {

Node head = new Node();

head.data = 1;

head.next = new Node();

head.next.data = 2;

head.next.next = new Node();

head.next.next.data = 3;

head.next.next.next = null;

return head;

}

class Node {

int data;

Node next;

}

Node createList() {

Node head = new Node();

head.data = 1;

head.next = new Node();

head.next.data = 2;

head.next.next = new Node();

head.next.next.data = 3;

head.next.next.next = null;

return head;

}

Doubly Linked List

A doubly linked list extends the singly linked list by incorporating bidirectional pointers in each node, enabling traversal in both forward and backward directions. Each node typically consists of three fields: the data element, a pointer to the next node in the sequence, and a pointer to the previous node. The head node's previous pointer is set to null, and the tail node's next pointer is set to null, maintaining the linear structure while allowing efficient access from either end.[13][15] The following pseudocode illustrates a basic node structure in C-like syntax:struct Node {

int [data](/page/Data); // The [data](/page/Data) stored in the node

struct Node* next; // Pointer to the next node

struct Node* prev; // Pointer to the previous node

};

struct Node {

int [data](/page/Data); // The [data](/page/Data) stored in the node

struct Node* next; // Pointer to the next node

struct Node* prev; // Pointer to the previous node

};

Variants

Circular Linked List

A circular linked list is a variant of the linked list data structure in which the last node connects back to the first node, creating a closed loop that enables continuous traversal without a defined end. This structure eliminates null terminators, with the tail node's next pointer referencing the head in a singly linked variant, or the head node's previous pointer referencing the tail in a doubly linked variant. Unlike linear linked lists, which terminate with a null pointer, circular lists form a cycle that simplifies certain operations involving repeated access to elements in sequence. There are two primary types of circular linked lists: singly circular, which allows unidirectional traversal along the loop via next pointers, and doubly circular, which supports bidirectional traversal using both next and previous pointers. In a singly circular list, each node contains data and a single next pointer, with the loop maintained by setting the tail's next to the head. For doubly circular lists, nodes include both next and previous pointers, ensuring the head's previous points to the tail and the tail's next points to the head, providing symmetry for forward and backward navigation. Circular linked lists are particularly efficient for representing cyclic data patterns, such as in round-robin scheduling algorithms within operating systems, where processes are managed in a repeating cycle to ensure fair resource allocation. For instance, in input-queued switches, deficit round-robin scheduling employs circular linked lists to cycle through ports systematically, avoiding the need to reset pointers after reaching the end. Other applications include modeling computer networks, where nodes represent interconnected devices in a loop without a natural starting or ending point. Traversal in a circular linked list begins at any node, typically the head, and continues until returning to the starting point to visit all elements. For a singly circular list, the process can use a do-while loop: initialize current to head, then do { process current's data; current = current.next; } while (current != head). This ensures all nodes are visited, including in single-node cases, and prevents infinite traversal by checking return to start. As an example of maintaining the loop during insertion in a singly circular list, consider adding a new node at the end. The following pseudocode illustrates the process, assuming an existing list with a head pointer:if head is null:

create new node

new.next = new

head = new

else:

temp = head

while temp.next != head:

temp = temp.next

create new node

temp.next = new

new.next = head

if head is null:

create new node

new.next = new

head = new

else:

temp = head

while temp.next != head:

temp = temp.next

create new node

temp.next = new

new.next = head

Multiply Linked List

A multiply linked list is a variation of the linked list data structure where each node contains two or more link fields, enabling the same set of data records to be traversed in multiple different orders or along various dimensions.[18] This extends the linear connectivity of simpler singly or doubly linked lists to support more complex relationships.[19] In terms of structure, a common implementation is the two-dimensional multiply linked list used for representing sparse matrices, where non-zero elements are stored as nodes with pointers for row-wise and column-wise traversal. Each node typically holds the row index, column index, data value, a pointer to the next node in the same row (e.g.,right), and a pointer to the next node in the same column (e.g., down). For instance, the following C-like structure illustrates a basic node:

struct Node {

int row;

int col;

int data;

struct Node* right; // Next node in the same row

struct Node* down; // Next node in the same column

};

struct Node {

int row;

int col;

int data;

struct Node* right; // Next node in the same row

struct Node* down; // Next node in the same column

};

Other Specialized Variants

List handles provide an abstract interface to the root of a linked list, allowing dynamic manipulation such as insertion or deletion without directly exposing the internal node structure to the user.[20] By encapsulating the head pointer and related metadata within a handle object, this variant supports safer operations in object-oriented systems and facilitates garbage collection or memory management.[20] Hybrid structures combine linked lists with alternative techniques to optimize performance. Skip lists augment a singly linked list by adding multiple levels of forward pointers at exponentially increasing intervals, enabling faster search through probabilistic layer selection.[21] A simple skip list node might be represented in pseudocode as:class SkipListNode {

int value;

SkipListNode* next[MaxLevels]; // Array of pointers for different levels

int level; // Highest level for this node

}

class SkipListNode {

int value;

SkipListNode* next[MaxLevels]; // Array of pointers for different levels

int level; // Highest level for this node

}

Structural Elements

Sentinel Nodes

Sentinel nodes, also known as dummy or placeholder nodes, are specially designated nodes in a linked list that do not store actual data but serve to mark boundaries and simplify structural management.[15] These nodes are typically positioned at the front (header sentinel), rear (trailer sentinel), or both ends of the list, with their pointers configured to connect to the first or last real node, thereby providing a consistent structure regardless of the list's size.[23] In this way, a sentinel node acts as a traversal terminator or boundary marker, avoiding the need to handle null pointers directly in many cases.[24] The primary types of sentinel nodes include front sentinels for singly linked lists, which precede the first data node, and rear sentinels for lists where operations at the end are frequent.[25] In doubly linked lists, both header and trailer sentinels are commonly used, with the header's next pointer linking to the first node and its previous pointer set to null, while the trailer's previous points to the last node and its next to null.[15] This dual-sentinel approach ensures bidirectional navigation without special boundary checks.[26] One key benefit of sentinel nodes is the elimination of special cases during operations, such as checking for empty lists or insertions at the beginning or end, which streamlines code implementation and reduces errors.[27] For instance, an empty list can be represented simply by having the sentinel's pointers reference itself or null, maintaining uniformity with non-empty lists.[28] This design promotes cleaner, more robust algorithms by treating boundaries as regular nodes.[29] In pseudocode, a basic singly linked list with a head sentinel might be initialized as follows:class Node:

data = None

next = None

sentinel = Node() # No data stored

sentinel.next = None # Points to first real node or None for empty list

# To insert a new node at the front:

new_node = Node()

new_node.data = value

new_node.next = sentinel.next

sentinel.next = new_node

class Node:

data = None

next = None

sentinel = Node() # No data stored

sentinel.next = None # Points to first real node or None for empty list

# To insert a new node at the front:

new_node = Node()

new_node.data = value

new_node.next = sentinel.next

sentinel.next = new_node

Empty Lists

In linked lists, an empty list is conventionally represented by setting the head pointer to null, signifying that no nodes have been allocated or linked together.[10] This approach ensures that the list structure requires zero memory for nodes in the absence of elements, distinguishing it from non-empty states where the head points to the first node.[30] Detection of an empty list is straightforward and involves a simple null check on the head pointer, which serves as the primary indicator for emptiness in standard implementations.[2] A common utility function for this purpose is theisEmpty method, exemplified in the following pseudocode:

boolean isEmpty(Node head) {

return head == null;

}

boolean isEmpty(Node head) {

return head == null;

}

List Handles

In data structures, a list handle refers to an opaque pointer or object that encapsulates the head pointer (and optionally the tail pointer) of a linked list, serving as the primary identifier and access point for the structure without exposing the underlying node details.[33] This abstraction allows users to manipulate the list through a controlled interface, preventing direct access to internal pointers that could lead to errors like dangling references or invalid modifications.[34] The use of list handles promotes encapsulation, a key principle in object-oriented programming, by bundling the list's state and operations within a single entity, thereby hiding implementation specifics from client code.[35] This approach simplifies memory management, as the handle manages dynamic allocation and deallocation of nodes, reducing the risk of manual pointer errors in languages without built-in garbage collection.[33] For instance, in Java, aList class typically declares a private Node reference for the head, ensuring that all interactions occur via public methods like add or remove, which maintain the list's integrity.[35]

Operations on the linked list are exclusively performed through methods provided by the handle, such as insertion at the head or tail, which internally update the encapsulated pointers while keeping the linking mechanism hidden from the user.[33] This design not only enforces safe usage but also facilitates easier maintenance and extension of the data structure.[34]

In environments with automatic garbage collection, list handles play a crucial role by acting as roots during the collection process, enabling the runtime to trace and reclaim unreferenced nodes linked from the handle, thus preventing memory leaks in complex structures.[36] This integration ensures that as long as the handle remains reachable, its associated nodes are preserved, and upon the handle becoming unreachable, the entire subgraph of nodes can be efficiently collected.[37]

Operations

Insertion and Deletion

Insertion operations in a singly linked list involve creating a new node and updating pointers to incorporate it into the structure, with efficiency varying by location. Inserting at the head is constant time, requiring only the creation of a new node whose next pointer points to the current head, followed by updating the head to the new node. This approach handles the empty list case seamlessly by setting the head directly to the new node if the list was previously empty.[38] For insertion at the tail or a specific position, traversal from the head is necessary to reach the appropriate point, resulting in O(n worst-case time complexity where n is the number of nodes. To insert after a specific node p, the algorithm sets the new node's next pointer to p's current next, then updates p's next to the new node; if inserting at the tail, p is the last node found via traversal. In the empty list case, this defaults to head insertion. Pseudocode for insertion after node p (assuming p is not null) is as follows:create new_node with value

new_node.next = p.next

p.next = new_node

create new_node with value

new_node.next = p.next

p.next = new_node

q.next = x.next

// Free x if necessary

q.next = x.next

// Free x if necessary

head = head.next

head = head.next

Traversal and Search

Traversal of a singly linked list begins at the head node and proceeds linearly by following each node's next pointer until reaching a null reference, allowing access to all elements in sequence. This process is fundamental for examining or processing list contents without modification. The standard iterative pseudocode for traversal is as follows:current = head

while current ≠ null do

process(current.data)

current = current.next

end while

current = head

while current ≠ null do

process(current.data)

current = current.next

end while

length = 0

current = head

while current ≠ null do

length = length + 1

current = current.next

end while

return length

length = 0

current = head

while current ≠ null do

length = length + 1

current = current.next

end while

return length

max_value = head.data

current = head.next

while current ≠ null do

if current.data > max_value then

max_value = current.data

end if

current = current.next

end while

return max_value

max_value = head.data

current = head.next

while current ≠ null do

if current.data > max_value then

max_value = current.data

end if

current = current.next

end while

return max_value

current = head

while current ≠ null do

if current.data = target then

return current

end if

current = current.next

end while

return null // target not found

current = head

while current ≠ null do

if current.data = target then

return current

end if

current = current.next

end while

return null // target not found

if head = null then return

start = head

current = head

repeat

process(current.data)

current = current.next

until current = start

if head = null then return

start = head

current = head

repeat

process(current.data)

current = current.next

until current = start

Additional Operations

Linked lists support various higher-level operations that manipulate the structure as a whole, such as reversal, concatenation, copying, and sorting. These operations are essential for applications requiring dynamic reconfiguration of list order or combination without excessive overhead. Reversal of a singly linked list rearranges the nodes so that the last node becomes the first, reversing the direction of all links. The standard iterative algorithm employs three pointers—previous (initialized to null), current (starting at the head), and next—to traverse the list in O(n) time while using O(1) extra space, by repeatedly storing the next node, redirecting the current node's next pointer to previous, and advancing the pointers.[14] A recursive approach achieves the same complexity by reversing the tail recursively and then attaching the original head as the new tail, though it uses O(n) stack space due to the recursion depth.[14] Here is pseudocode for the iterative reversal:function reverseList(head):

prev = null

current = head

while current != null:

nextTemp = current.next

current.next = prev

prev = current

current = nextTemp

return prev

function reverseList(head):

prev = null

current = head

while current != null:

nextTemp = current.next

current.next = prev

prev = current

current = nextTemp

return prev

Trade-offs

Linked Lists vs. Dynamic Arrays

Linked lists and dynamic arrays (also known as resizable arrays or vectors) represent two fundamental approaches to implementing linear data structures, each with distinct trade-offs in space and time efficiency. Linked lists consist of nodes where each stores data and a reference to the next node, enabling dynamic growth without preallocation. In contrast, dynamic arrays maintain elements in a contiguous block of memory that can be resized as needed, typically by allocating a larger array and copying elements when capacity is exceeded. These differences lead to varying performance characteristics depending on the operations performed.Space Efficiency

Linked lists require additional space for pointers or references in each node, resulting in an O(n) overhead proportional to the number of elements, where each pointer typically consumes 4 or 8 bytes depending on the system architecture. This overhead can be significant for small data elements, as each node allocates memory separately in the heap. Dynamic arrays, however, store elements contiguously without per-element pointers, achieving better space locality and minimal overhead per element, though they may temporarily waste space equal to up to half the current capacity during resizing phases. As a rule, linked lists are more space-efficient for lists with highly variable sizes where exact allocation is preferred, while dynamic arrays suit scenarios with predictable or stable sizes to minimize wasted space from over-allocation during resizing. For instance, if data elements are large (e.g., structs with substantial fields), the pointer overhead in linked lists becomes negligible relative to the data size.Time Complexity

The core time trade-offs arise from access patterns and modifications. Random access to an element by index is O(1) in dynamic arrays due to direct offset calculation from the base address, but O(n) in linked lists, requiring traversal from the head. Insertion and deletion at known positions (e.g., head or tail, or given a direct node pointer) are O(1) in linked lists, as they involve only pointer adjustments without shifting elements. In dynamic arrays, insertions or deletions in the middle or beginning require O(n) time to shift subsequent elements, though appends to the end are amortized O(1) due to occasional resizing. The following table summarizes average-case time complexities for common list operations, assuming a singly linked list without tail pointer and a dynamic array with doubling resize strategy:| Operation | Dynamic Array | Linked List |

|---|---|---|

| Access by index | O(1) | O(n) |

| Insert at beginning | O(n) | O(1) |

| Insert at end | Amortized O(1) | O(n) (O(1) with tail) |

| Insert at arbitrary position | O(n) | O(1) (if position known) |

| Delete at beginning | O(n) | O(1) |

| Delete at end | Amortized O(1) | O(n) (O(1) with tail) |

| Delete at arbitrary position | O(n) | O(1) (if position known) |

| Search (unsorted) | O(n) | O(n) |

When to Choose Each Structure

Dynamic arrays are ideal for applications requiring fast lookups or iterations over the entire structure, such as in many standard library implementations (e.g., Java's ArrayList or C++'s std::vector), where O(1) access dominates. Linked lists are better suited for scenarios with frequent insertions and deletions at non-end positions, avoiding the shifting costs of arrays, particularly when the list size is unknown or fluctuates widely. A brief reference to internal variants: singly linked lists suffice for forward-only operations, while doubly linked lists add space for backward pointers but enable O(1) end deletions with a tail pointer, as the previous link allows direct updates without traversal.Example: Queue Implementation

Consider implementing a queue, where enqueue adds to the rear and dequeue removes from the front. A linked list achieves O(1) time for both operations by maintaining head and tail pointers, with no element shifting required. In a dynamic array, enqueue is amortized O(1) via resizing, but dequeue necessitates O(n) shifting of all elements to fill the front gap, making it inefficient for large queues unless using a circular buffer variant. This demonstrates linked lists' advantage in preserving operation efficiency for dynamic workloads like breadth-first search or task scheduling.Amortized Analysis

Dynamic arrays' resizing incurs occasional O(n) costs when capacity is exceeded, but by doubling the size each time (e.g., from 2^k to 2^{k+1}), the total cost over m insertions is O(m), yielding amortized O(1) per operation via the accounting method—charging extra "credits" during cheap inserts to cover resizes. Linked lists avoid such bursts, with truly constant O(1) per insertion or deletion at endpoints, though traversal remains linear without indexing support. This amortized efficiency makes dynamic arrays preferable for append-heavy workloads, as verified in standard analyses.Singly vs. Doubly Linked

A singly linked list consists of nodes where each node contains data and a single pointer to the next node in the sequence, enabling unidirectional traversal from the head to the tail. In contrast, a doubly linked list includes an additional pointer in each node to the previous node, allowing bidirectional traversal and more flexible navigation. This structural difference impacts both memory usage and operational efficiency, with the choice between them depending on the application's requirements for directionality and performance.[44] Doubly linked lists require approximately twice the pointer storage per node compared to singly linked lists, as each node stores both next and previous pointers, leading to higher memory overhead—typically an extra pointer's worth of space (e.g., 8 bytes on a 64-bit system) per node. This extra space enables direct access to adjacent nodes in both directions without additional searches, which is beneficial when frequent backward operations are needed, but it can be prohibitive in memory-constrained environments where singly linked lists suffice for forward-only access. In terms of time complexity, both structures support O(1) insertion and deletion at the head if a head pointer is maintained. However, operations at the tail or in the middle differ significantly: singly linked lists require O(n time for tail insertions or deletions due to the need to traverse from the head to locate the last node (unless a tail pointer is added, which complicates updates), while doubly linked lists achieve O(1) for these with direct previous/next access. Traversal and search remain O(n for both in the worst case, but doubly linked lists allow reverse traversal in O(n without restarting from the head. The following table summarizes key operation complexities, assuming access to the head (and tail where applicable) and no direct node pointer for middle operations:| Operation | Singly Linked List | Doubly Linked List |

|---|---|---|

| Insert at head | O(1) | O(1) |

| Insert at tail | O(n) | O(1) |

| Delete at head | O(1) | O(1) |

| Delete at tail | O(n) | O(1) |

| Insert/delete in middle (with node pointer) | O(1) for insert; O(n) for delete (needs prev) | O(1) |

| Traversal (full) | O(n) (forward only) | O(n) (bidirectional) |

| Search | O(n) | O(n) |

Linear vs. Circular Linking