Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Emona

View on WikipediaEmona (early Medieval Greek: Ἤμονα)[1] or Aemona (short for Colonia Iulia Aemona) was a Roman castrum, located in the area where the navigable Nauportus[2] River came closest to Castle Hill,[3] serving the trade between the city's settlers – colonists from the northern part of Roman Italy – and the rest of the empire. Emona was the region's easternmost city,[4] although it was assumed formerly that it was part of the Pannonia or Illyricum, but archaeological findings from 2008 proved otherwise.

Key Information

The Visigoths camped by Emona in the winter of 408/9, the Huns attacked it during their campaign of 452, the Langobards passed through on their way to Italy in 568, and then came incursions by the Avars and Slavs. The ancient cemetery in Dravlje indicates that the original inhabitants and invaders were able to live peacefully side by side for several decades. After the first half of the 6th century, there was no life left in Emona.[3] The 18th-century Ljubljana Renaissance elite shared the interest in Antiquity with the rest of Europe, attributing the founding of Ljubljana to the mythical Jason and the Argonauts.[3] Other ancient Roman towns located in present-day Slovenia include Nauportus (now Vrhnika), Celeia (now Celje), Neviodunum (now the village of Drnovo) and Poetovio (now Ptuj).

History

[edit]

During the 1st century BC a Roman military stronghold was built on the site of the present Ljubljana, below Castle hill. Construction of the Roman settlement of Emona, fortified with strong walls, followed in AD 14. It had a population of 5,000 to 6,000 people, mostly merchants and craftsmen. The town had its own goddess, Equrna, and was also an important Early Christian centre. Emona's administrative territory or ager stretched from Atrans (Trojane) along the Karawanks mountains towards the north, near Višnja Gora to the east, along the Kolpa River in the south, and bordered to the west with the territory of Aquileia at the village of Bevke.

According to Ammianus Marcellinus, one of the reasons for the war between Licinius and Constantine the Great was that Licinius destroyed the busts and statues of Constantine at Emona.[8]

After few months of occupation in 388, the citizens of Emona saluted Emperor Theodosius I entering the liberated city after the victorious Battle of the Save, where Theodosius I defeated the army of the Roman usurper Magnus Maximus.

Historical descriptions

[edit]According to Herodotus, Emona was founded by Jason, when he travelled through the country with the Argonauts, and named by him in honour of his Thessalian homeland. Sozomen wrote that when the Argonauts left from the Aeetes, they returned from a different route, crossed the sea of Scythia, sailed through some of the rivers there, and when they were near the shores of Italy, they built a city in order to stay at the winter, which they called Emona.[1] Zosimus wrote that after they left from the Aeetes, they arrived at the mouth of the Ister River which it discharges itself into the Black Sea and they went up that river against the stream, by the help of oars and convenient gales of wind. After they managed to do it, they built the city of Emona as a memorial of their arrival there.[9]

According to the 18th-century historian Johann Gregor Thalnitscher, the original predecessor of Emona was founded c. 1222 BC. (The date, although based on legend and poetic speculation, actually fits in both with Herodotus' account and the date of the earliest archaeological remains found so far)[citation needed]

According to 1938 article by the historian Balduin Saria, Emona was founded in late AD 14 or early AD 15, on the site of the Legio XV Apollinaris, after it left for Carnuntum, by a decree of Emperor Augustus and completed by his successor, Emperor Tiberius. Later archaeological findings have not rejected nor clearly confirmed this hypothesis and it is currently (as of 2014[update]) most widely accepted.[10]

Location and layout

[edit]

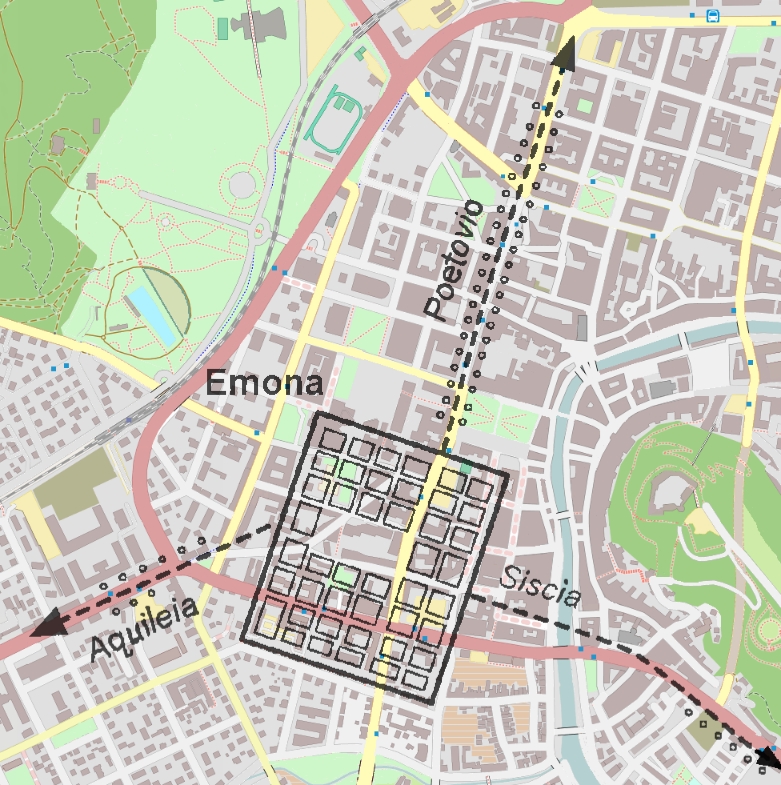

The location of Emona overlaps with the southwest part of the old nucleus of the modern city of Ljubljana. In a rectangle with a central square or forum and a system of rectangular intersecting streets, Emona was laid out as a typical Roman town. According to Roman custom, there were cemeteries along the northern, western, and eastern thoroughfares into the city – from the directions of Celeia, Aquileia, and Neviodunum.[12] The wider area surrounding the town saw the development of typical Roman countryside: villages, hamlets, estates, and brickworks.[3]

Archaeological findings

[edit]

Archaeological findings have been found in every construction project in the center of Ljubljana. Intensive archaeological research on Emona dates back 100 years, although it was the Roman town was portrayed from the 17th century onward. Numerous remains have been excavated there, such as parts of the Roman wall, residential houses, statues, tombstones, several mosaics, and parts of the early Christian baptistery, which can be still seen today.[10]

Regarding its location within Roman Italy, in 2001 a boundary stone between Aquileia and Emona was discovered in the vicinity of Bevke in the bed of the Ljubljanica River. The stone is made of Aurisina limestone. Because similar stones were only used to demarcate two communities belonging to the same Roman province and because it is not disputed that Aquileia belonged to Roman Italy, this means that both towns belonged to Italy and that Emona was never part of Illyricum (or, later, of the province of Pannonia).[4]

Archaeological parks and preserving of the heritage

[edit]The architect Jože Plečnik redesigned the remains of the Roman walls: he cut two new passages to create a link to Snežnik Street (Slovene: Snežniška ulica) and Murnik Street (Slovene: Murnikova ulica), and behind the walls he arranged a park displaying architectural elements from Antiquity, with a stone monument collection in the Emona city gate. Above the passageway to Murnik Street he set up a pyramid, which he covered with turf. After the Second World War, attempts were made to embed references to Emona grid into modern Ljubljana, with the Roman forum becoming part of the Ferant Park apartment blocks and an echo of the rotunda located along Slovenia Street (Slovene: Slovenska cesta).[3]

Bishopric

[edit]A Christian diocese of Aemona was originally based in the city, from the late 4th to the late 6th century.

Its bishop Maximus participated in the Council of Aquileia, 381, which condemned Arianism.

It had intensive contacts with the ecclesiastical circle of Milan, reflected in the architecture of the early Christian complex along Erjavec Street in present-day Ljubljana.

Emona in literary fiction

[edit]- Emona is the setting of a 1978 novel Tujec v Emoni (Stranger in Emona) by Mira Mihelič.

- Emona is mentioned in Elizabeth Kostova's debut novel The Historian.

- The four volumes of the 2014 series Rimljani na naših tleh (Romans on our soil) by Ivan Sivec describe Emona in various epochs.

- Several chapters of the novel series Romanike are set in Emona.[13]

Gallery

[edit]-

True to scale 1st century AD Emona with insulas, wall, gates and towers. Note high level of modern streets and walls still overlapping

-

South Emona's wall with information panel. This location is one of the spots on a 2 km (1 mi) footpath, connecting the locations of ten ancient sites in present-day Ljubljana. Suggested starting point: City Museum of Ljubljana.

-

Excavations at the building site of the planned new National and University Library of Slovenia. One of the discoveries was the ancient Roman public bath house.[14]

-

A depiction of the Argonauts building Emona, published in the Glory of the Duchy of Carniola (1689) by Johann Weikhard von Valvasor

-

Early Christian centre in Emona

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Sozomenos, Ecclesiastical History, §1.6". Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- ^ Kos, Marjeta Šašel (2015). The Disappearing Tombstone and Other Stories from Emona. Založba ZRC. p. 6. ISBN 978-9612547646.

- ^ a b c d e Exhibition catalogue Emona: myth and reality Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine; Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana 2010

- ^ a b Šašel Kos, M. (2002) "The boundary stone between Aquileia and Emona", Arheološki Vestnik 53, pp. 373–382.

- ^ "O najstarejšem napisu iz Emone. Kronika (Ljubljana) 3(2): 110–113. URN:NBN:SI:doc-F259ED85 from http://www.dlib.si" (.pdf). Jaroslav Šašel. 1955. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Roman Emona". Culture.si. Ministry of culture of the republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Emona, Legacy of a Roman City". Culture.si. Ministry of culture of the republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, History, V1.5.15

- ^ Zosimus, New History, 5.29

- ^ a b Šašel Kos, Marjeta (September 2012). "2000 let Emone? Kaj bomo praznovali?" [2000 Years of Emona? What Will We Celebrate?] (PDF). Ljubljana: glasilo Mestne občine Ljubljana [Ljubljana: The Bulletin of the City Municipality of Ljubljana] (in Slovenian). 17 (7): 28–29. ISSN 1318-797X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-20.

- ^ "Emonski vodovod". DEDI. Ministry of higher education, science and technology of the republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Stemberger, Kaja (2019-12-12). "Full archives, meaningless data? What artefacts can tell about age and gender at large-scale cemeteries (case study Colonia Iulia Emona)". Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal. 2 (1): 8. doi:10.16995/traj.369. ISSN 2515-2289.

- ^ The Romanike Series Archived 2016-08-06 at the Wayback Machine, by Codex Regius (2006-2014)

- ^ Bernarda Županek (2010) "Emona, Legacy of a Roman City", Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana, Ljubljana.

Further reading

[edit]- Ljudmila Plesničar Gec. Urbanizem Emone / The Urbanism of Emona. City Museum of Ljubljana; The Research Institute of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities. Ljubljana, 1999.

- MS Kos. Emona was in Italy not Pannonia. 2003

External links

[edit]- Bernarda Županek: Emona: mesto v imperiju/Emona: A City of the Empire (Slovene, English)

- Interactive archaeological map of Emona on top of map of Ljubljana. Geopedia.si.

- Early Christian Centre of Emona. 3D images. Burger.si.

- Panoramic virtual tour of the ancient wall of Emona

- Culture.si articles about the city: Roman Emona, Emona, Legacy of a Roman City

- A day in Emona, short movie about life in Roman settlement

![Excavations at the building site of the planned new National and University Library of Slovenia. One of the discoveries was the ancient Roman public bath house.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Emona3.JPG/330px-Emona3.JPG)