Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Equal temperament

View on Wikipedia

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or tuning system that approximates just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into steps such that the ratio of the frequencies of any adjacent pair of notes is the same. This system yields pitch steps perceived as equal in size, due to the logarithmic changes in pitch frequency.[2]

In classical music and Western music in general, the most common tuning system since the 18th century has been 12 equal temperament (also known as 12 tone equal temperament, 12 TET or 12 ET, informally abbreviated as 12 equal), which divides the octave into 12 parts, all of which are equal on a logarithmic scale, with a ratio equal to the 12th root of 2, ( ≈ 1.05946). That resulting smallest interval, 1/12 the width of an octave, is called a semitone or half step. In Western countries the term equal temperament, without qualification, generally means 12 TET.

In modern times, 12 TET is usually tuned relative to a standard pitch of 440 Hz, called A 440, meaning one note, A, is tuned to 440 hertz and all other notes are defined as some multiple of semitones away from it, either higher or lower in frequency. The standard pitch has not always been 440 Hz; it has varied considerably and generally risen over the past few hundred years.[3]

Other equal temperaments divide the octave differently. For example, some music has been written in 19 TET and 31 TET, while the Arab tone system uses 24 TET.

Instead of dividing an octave, an equal temperament can also divide a different interval, like the equal-tempered version of the Bohlen–Pierce scale, which divides the just interval of an octave and a fifth (ratio 3:1), called a "tritave" or a "pseudo-octave" in that system, into 13 equal parts.

For tuning systems that divide the octave equally, but are not approximations of just intervals, the term equal division of the octave, or EDO can be used.

Unfretted string ensembles, which can adjust the tuning of all notes except for open strings, and vocal groups, who have no mechanical tuning limitations, sometimes use a tuning much closer to just intonation for acoustic reasons. Other instruments, such as some wind, keyboard, and fretted instruments, often only approximate equal temperament, where technical limitations prevent exact tunings.[4] Some wind instruments that can easily and spontaneously bend their tone, most notably trombones, use tuning similar to string ensembles and vocal groups.

General properties

[edit]In an equal temperament, the distance between two adjacent steps of the scale is the same interval. Because the perceived identity of an interval depends on its ratio, this scale in even steps is a geometric sequence of multiplications. (An arithmetic sequence of intervals would not sound evenly spaced and would not permit transposition to different keys.) Specifically, the smallest interval in an equal-tempered scale is the ratio:

where the ratio r divides the ratio p (typically the octave, which is 2:1) into n equal parts. (See Twelve-tone equal temperament below.)

Scales are often measured in cents, which divide the octave into 1200 equal intervals (each called a cent). This logarithmic scale makes comparison of different tuning systems easier than comparing ratios, and has considerable use in ethnomusicology. The basic step in cents for any equal temperament can be found by taking the width of p above in cents (usually the octave, which is 1200 cents wide), called below w, and dividing it into n parts:

In musical analysis, material belonging to an equal temperament is often given an integer notation, meaning a single integer is used to represent each pitch. This simplifies and generalizes discussion of pitch material within the temperament in the same way that taking the logarithm of a multiplication reduces it to addition. Furthermore, by applying the modular arithmetic where the modulus is the number of divisions of the octave (usually 12), these integers can be reduced to pitch classes, which removes the distinction (or acknowledges the similarity) between pitches of the same name, e.g., c is 0 regardless of octave register. The MIDI encoding standard uses integer note designations.

General formulas for the equal-tempered interval

[edit]This section is missing information about the general formulas for the equal-tempered interval. (February 2019) |

Twelve-tone equal temperament

[edit]12 tone equal temperament, which divides the octave into 12 intervals of equal size, is the musical system most widely used today, especially in Western music.

History

[edit]The two figures frequently credited with the achievement of exact calculation of equal temperament are Zhu Zaiyu (also romanized as Chu-Tsaiyu. Chinese: 朱載堉) in 1584 and Simon Stevin in 1585. According to F.A. Kuttner, a critic of giving credit to Zhu,[5] it is known that Zhu "presented a highly precise, simple and ingenious method for arithmetic calculation of equal temperament mono-chords in 1584" and that Stevin "offered a mathematical definition of equal temperament plus a somewhat less precise computation of the corresponding numerical values in 1585 or later."

The developments occurred independently.[6](p200)

Kenneth Robinson credits the invention of equal temperament to Zhu[7][b] and provides textual quotations as evidence.[8] In 1584 Zhu wrote:

- I have founded a new system. I establish one foot as the number from which the others are to be extracted, and using proportions I extract them. Altogether one has to find the exact figures for the pitch-pipers in twelve operations.[9][8]

Kuttner disagrees and remarks that his claim "cannot be considered correct without major qualifications".[5] Kuttner proposes that neither Zhu nor Stevin achieved equal temperament and that neither should be considered its inventor.[10]

China

[edit]

Chinese theorists had previously come up with approximations for 12 TET, but Zhu was the first person to mathematically solve 12 tone equal temperament,[11] which he described in two books, published in 1580[12] and 1584.[9][13] Needham also gives an extended account.[14]

Zhu obtained his result by dividing the length of string and pipe successively by ≈ 1.059463, and for pipe length by ≈ 1.029302,[15] such that after 12 divisions (an octave), the length was halved.

Zhu created several instruments tuned to his system, including bamboo pipes.[16]

Europe

[edit]Some of the first Europeans to advocate equal temperament were lutenists Vincenzo Galilei, Giacomo Gorzanis, and Francesco Spinacino, all of whom wrote music in it.[17][18][19][20]

Simon Stevin was the first to develop 12 TET based on the twelfth root of two, which he described in van de Spiegheling der singconst (c. 1605), published posthumously in 1884.[21]

Plucked instrument players (lutenists and guitarists) generally favored equal temperament,[22] while others were more divided.[23] In the end, 12-tone equal temperament won out. This allowed enharmonic modulation, new styles of symmetrical tonality and polytonality, atonal music such as that written with the 12-tone technique or serialism, and jazz (at least its piano component) to develop and flourish.

Mathematics

[edit]

In 12 tone equal temperament, which divides the octave into 12 equal parts, the width of a semitone, i.e. the frequency ratio of the interval between two adjacent notes, is the twelfth root of two:

This interval is divided into 100 cents.

Calculating absolute frequencies

[edit]To find the frequency, Pn, of a note in 12 TET, the following formula may be used:

In this formula Pn represents the pitch, or frequency (usually in hertz), that is to be calculated. Pa is the frequency of a reference pitch. The indes numbers n and a are the labels assigned to the desired pitch (n) and the reference pitch (a). These two numbers are from a list of consecutive integers assigned to consecutive semitones. For example, A4 (the reference pitch) is the 49th key from the left end of a piano (tuned to 440 Hz), and C4 (middle C), and F♯4 are the 40th and 46th keys, respectively. These numbers can be used to find the frequency of C4 and F♯4:

Converting frequencies to their equal temperament counterparts

[edit]To convert a frequency (in Hz) to its equal 12 TET counterpart, the following formula can be used:

- where in general

En is the frequency of a pitch in equal temperament, and Ea is the frequency of a reference pitch. For example, if we let the reference pitch equal 440 Hz, we can see that E5 and C♯5 have the following frequencies, respectively:

- where in this case

- where in this case

Comparison with just intonation

[edit]The intervals of 12 TET closely approximate some intervals in just intonation.[24] The fifths and fourths are almost indistinguishably close to just intervals, while thirds and sixths are further away.

In the following table, the sizes of various just intervals are compared to their equal-tempered counterparts, given as a ratio as well as cents.

Interval Name Exact value in 12 TET Decimal value in 12 TET Pitch in Just intonation interval Cents in just intonation 12 TET cents

tuning errorUnison (C) 20⁄12 = 1 1 0 1/1 = 1 0 0 Minor second (D♭) 21⁄12 = 1.059463 100 16/15 = 1.06666... 111.73 -11.73 Major second (D) 22⁄12 = 1.122462 200 9/8 = 1.125 203.91 -3.91 Minor third (E♭) 23⁄12 = 1.189207 300 6/5 = 1.2 315.64 -15.64 Major third (E) 24⁄12 = 1.259921 400 5/4 = 1.25 386.31 +13.69 Perfect fourth (F) 25⁄12 = 1.33484 500 4/3 = 1.33333... 498.04 +1.96 Tritone (G♭) 26⁄12 = 1.414214 600 64/45= 1.42222... 609.78 -9.78 Perfect fifth (G) 27⁄12 = 1.498307 700 3/2 = 1.5 701.96 -1.96 Minor sixth (A♭) 28⁄12 = 1.587401 800 8/5 = 1.6 813.69 -13.69 Major sixth (A) 29⁄12 = 1.681793 900 5/3 = 1.66666... 884.36 +15.64 Minor seventh (B♭) 210⁄12 = 1.781797 1000 16/9 = 1.77777... 996.09 +3.91 Major seventh (B) 211⁄12 = 1.887749 1100 15/8 = 1.875 1088.270 +11.73 Octave (C) 212⁄12 = 2 2 1200 2/1 = 2 1200.00 0

Seven-tone equal division of the fifth

[edit]Violins, violas, and cellos are tuned in perfect fifths (G D A E for violins and C G D A for violas and cellos), which suggests that their semitone ratio is slightly higher than in conventional 12 tone equal temperament. Because a perfect fifth is in 3:2 relation with its base tone, and this interval comprises seven steps, each tone is in the ratio of to the next (100.28 cents), which provides for a perfect fifth with ratio of 3:2, but a slightly widened octave with a ratio of ≈ 517:258 or ≈ 2.00388:1 rather than the usual 2:1, because 12 perfect fifths do not equal seven octaves.[25] During actual play, however, violinists choose pitches by ear, and only the four unstopped pitches of the strings are guaranteed to exhibit this 3:2 ratio.

Other equal temperaments

[edit]Five-, seven-, and nine-tone temperaments in ethnomusicology

[edit]

Five- and seven-tone equal temperament (5 TET ⓘ and 7 TETⓘ ), with 240 cent ⓘ and 171 cent ⓘ steps, respectively, are fairly common.

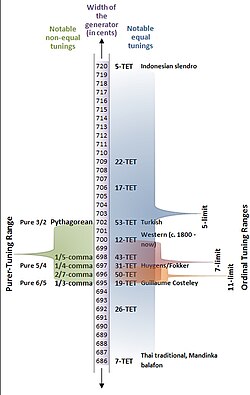

5 TET and 7 TET mark the endpoints of the syntonic temperament's valid tuning range, as shown in Figure 1.

- In 5 TET, the tempered perfect fifth is 720 cents wide (at the top of the tuning continuum), and marks the endpoint on the tuning continuum at which the width of the minor second shrinks to a width of 0 cents.

- In 7 TET, the tempered perfect fifth is 686 cents wide (at the bottom of the tuning continuum), and marks the endpoint on the tuning continuum, at which the minor second expands to be as wide as the major second (at 171 cents each).

5 tone and 9 tone equal temperament

[edit]According to Kunst (1949), Indonesian gamelans are tuned to 5 TET, but according to Hood (1966) and McPhee (1966) their tuning varies widely, and according to Tenzer (2000) they contain stretched octaves. It is now accepted that of the two primary tuning systems in gamelan music, slendro and pelog, only slendro somewhat resembles five-tone equal temperament, while pelog is highly unequal; however, in 1972 Surjodiningrat, Sudarjana and Susanto analyze pelog as equivalent to 9 TET (133-cent steps ⓘ).[26]

7-tone equal temperament

[edit]A Thai xylophone measured by Morton in 1974 "varied only plus or minus 5 cents" from 7 TET.[27] According to Morton,

- "Thai instruments of fixed pitch are tuned to an equidistant system of seven pitches per octave ... As in Western traditional music, however, all pitches of the tuning system are not used in one mode (often referred to as 'scale'); in the Thai system five of the seven are used in principal pitches in any mode, thus establishing a pattern of nonequidistant intervals for the mode."[28] ⓘ

A South American Indian scale from a pre-instrumental culture measured by Boiles in 1969 featured 175 cent seven-tone equal temperament, which stretches the octave slightly, as with instrumental gamelan music.[29]

Chinese music has traditionally used 7 TET.[c][d]

Various equal temperaments

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

- 19 EDO

- Many instruments have been built using 19 EDO tuning. Equivalent to 1 / 3 comma meantone, it has a slightly flatter perfect fifth (at 695 cents), but its minor third and major sixth are less than one-fifth of a cent away from just, with the lowest EDO that produces a better minor third and major sixth than 19 EDO being 232 EDO. Its perfect fourth (at 505 cents), is seven cents sharper than just intonation's and five cents sharper than 12 EDO's.

- 22 EDO

- 22 EDO is one of the most accurate EDOs to represent "superpythagorean" temperament (where 7:4 and 16:9 are the same interval). The perfect fifth is tuned sharp, resulting in four fifths and three fourths reaching supermajor thirds (9/7) and subminor thirds (7/6). One step closer to each other are the classical major and minor thirds (5/4 and 6/5).

- 23 EDO

- 23 EDO is the largest EDO that fails to approximate the 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 11th harmonics (3:2, 5:4, 7:4, 11:8) within 20 cents, but it does approximate some ratios between them (such as the 6:5 minor third) very well, making it attractive to microtonalists seeking unusual harmonic territory.

- 24 EDO

- 24 EDO, the quarter-tone scale, is particularly popular, as it represents a convenient access point for composers conditioned on standard Western 12 EDO pitch and notation practices who are also interested in microtonality. Because 24 EDO contains all the pitches of 12 EDO, musicians employ the additional colors without losing any tactics available in 12 tone harmony. That 24 is a multiple of 12 also makes 24 EDO easy to achieve instrumentally by employing two traditional 12 EDO instruments tuned a quarter-tone apart, such as two pianos, which also allows each performer (or one performer playing a different piano with each hand) to read familiar 12 tone notation. Various composers, including Charles Ives, experimented with music for quarter-tone pianos. 24 EDO also approximates the 11th and 13th harmonics very well, unlike 12 EDO.

- 26 EDO

- 26 is the denominator of a convergent to log2(7), tuning the 7th harmonic (7:4) with less than half a cent of error. Although it is a meantone temperament, it is a very flat one, with four of its perfect fifths producing a major third 17 cents flat (equated with the 11:9 neutral third). 26 EDO has two minor thirds and two minor sixths and could be an alternate temperament for barbershop harmony.

- 27 EDO

- 27 is the lowest number of equal divisions of the octave that uniquely represents all intervals involving the first eight harmonics. It tempers out the septimal comma but not the syntonic comma.

- 29 EDO

- 29 is the lowest number of equal divisions of the octave whose perfect fifth is closer to just than in 12 EDO, in which the fifth is 1.5 cents sharp instead of 2 cents flat. Its classic major third is roughly as inaccurate as 12 EDO, but is tuned 14 cents flat rather than 14 cents sharp. It also tunes the 7th, 11th, and 13th harmonics flat by roughly the same amount, allowing 29 EDO to match intervals such as 7:5, 11:7, and 13:11 very accurately. Cutting all 29 intervals in half produces 58 EDO, which allows for lower errors for some just tones.

- 31 EDO

- 31 EDO was advocated by Christiaan Huygens and Adriaan Fokker and represents a rectification of quarter-comma meantone into an equal temperament. 31 EDO does not have as accurate a perfect fifth as 12 EDO (like 19 EDO), but its major thirds and minor sixths are less than 1 cent away from just. It also provides good matches for harmonics up to 11, of which the seventh harmonic is particularly accurate.

- 34 EDO

- 34 EDO gives slightly lower total combined errors of approximation to 3:2, 5:4, 6:5, and their inversions than 31 EDO does, despite having a slightly less accurate fit for 5:4. 34 EDO does not accurately approximate the seventh harmonic or ratios involving 7, and is not meantone since its fifth is sharp instead of flat. It enables the 600 cent tritone, since 34 is an even number.

- 41 EDO

- 41 is the next EDO with a better perfect fifth than 29 EDO and 12 EDO. Its classical major third is also more accurate, at only six cents flat. It is not a meantone temperament, so it distinguishes 10:9 and 9:8, along with the classic and Pythagorean major thirds, unlike 31 EDO. It is more accurate in the 13 limit than 31 EDO.

- 46 EDO

- 46 EDO provides major thirds and perfect fifths that are both slightly sharp of just, and many[who?] say that this gives major triads a characteristic bright sound. The prime harmonics up to 17 are all within 6 cents of accuracy, with 10:9 and 9:5 a fifth of a cent away from pure. As it is not a meantone system, it distinguishes 10:9 and 9:8.

- 53 EDO

- 53 EDO has only had occasional use, but is better at approximating the traditional just consonances than 12, 19 or 31 EDO. Its extremely accurate perfect fifths make it equivalent to an extended Pythagorean tuning, as 53 is the denominator of a convergent to log2(3). With its accurate cycle of fifths and multi-purpose comma step, 53 EDO has been used in Turkish music theory. It is not a meantone temperament, which put good thirds within easy reach by stacking fifths; instead, like all schismatic temperaments, the very consonant thirds are represented by a Pythagorean diminished fourth (C-F♭), reached by stacking eight perfect fourths. It also tempers out the kleisma, allowing its fifth to be reached by a stack of six minor thirds (6:5).

- 58 EDO

- 58 equal temperament is a duplication of 29 EDO, which it contains as an embedded temperament. Like 29 EDO it can match intervals such as 7:4, 7:5, 11:7, and 13:11 very accurately, as well as better approximating just thirds and sixths.

- 72 EDO

- 72 EDO approximates many just intonation intervals well, providing near-just equivalents to the 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 11th harmonics. 72 EDO has been taught, written and performed in practice by Joe Maneri and his students (whose atonal inclinations typically avoid any reference to just intonation whatsoever). As it is a multiple of 12, 72 EDO can be considered an extension of 12 EDO, containing six copies of 12 EDO starting on different pitches, three copies of 24 EDO, and two copies of 36 EDO.

- 96 EDO

- 96 EDO approximates all intervals within 6.25 cents, which is barely distinguishable. As an eightfold multiple of 12, it can be used fully like the common 12 EDO. It has been advocated by several composers, especially Julián Carrillo.[34]

Other equal divisions of the octave that have found occasional use include 13 EDO, 15 EDO, 17 EDO, and 55 EDO.

2, 5, 12, 41, 53, 306, 665 and 15601 are denominators of first convergents of log2(3), so 2, 5, 12, 41, 53, 306, 665 and 15601 twelfths (and fifths), being in correspondent equal temperaments equal to an integer number of octaves, are better approximations of 2, 5, 12, 41, 53, 306, 665 and 15601 just twelfths/fifths than in any equal temperament with fewer tones.[35][36]

1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 12, 29, 41, 53, 200, ... (sequence A060528 in the OEIS) is the sequence of divisions of octave that provides better and better approximations of the perfect fifth. Related sequences containing divisions approximating other just intervals are listed in a footnote.[e]

Equal temperaments of non-octave intervals

[edit]The equal-tempered version of the Bohlen–Pierce scale consists of the ratio 3:1 (1902 cents) conventionally a perfect fifth plus an octave (that is, a perfect twelfth), called in this theory a tritave (ⓘ), and split into 13 equal parts. This provides a very close match to justly tuned ratios consisting only of odd numbers. Each step is 146.3 cents (ⓘ), or .

Wendy Carlos created three unusual equal temperaments after a thorough study of the properties of possible temperaments with step size between 30 and 120 cents. These were called alpha, beta, and gamma. They can be considered equal divisions of the perfect fifth. Each of them provides a very good approximation of several just intervals.[37] Their step sizes:

Alpha and beta may be heard on the title track of Carlos's 1986 album Beauty in the Beast.

Equal temperament with a non-integral number of notes per octave

[edit]While traditional equal temperaments—such as 12‑TET, 19‑TET, or 31‑TET—divide the octave into an integral number of equal parts, it is also possible to explore systems that divide the octave into a non-integral (often irrational) number. In such temperaments, the interval between successive pitches is defined by the ratio 2^(1/N), where N is not an integer. This results in irrational step sizes, meaning their multiples never exactly equal an octave.

Such tunings are of interest because, by deliberately sacrificing the octave (i.e., the second harmonic), they can yield a system that offers an improved overall approximation of other intervals in the harmonic series.

For example, in a tuning system based on 18.911‑EDO, the step size is 1200⁄18.911 ≈ 63.45 cents. Approximating the just perfect fifth (with a ratio of 3:2, or about 701.96 cents) requires about 11 steps:

- 11 steps × 63.45 cents ≈ 698.95 cents,

yielding an error of roughly 3 cents.

Similarly, for the just major third (with a ratio of 5:4, or about 386.31 cents), 6 steps are used:

- 6 steps × 63.45 cents ≈ 380.70 cents,

resulting in an error of approximately 5.61 cents.

Thus, although a perfect octave is absent, the consonance of many other intervals in these systems can be significantly higher than in integer-based equal temperaments.

Proportions between semitone and whole tone

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

In this section, semitone and whole tone may not have their usual 12 EDO meanings, as it discusses how they may be tempered in different ways from their just versions to produce desired relationships. Let the number of steps in a semitone be s, and the number of steps in a tone be t.

There is exactly one family of equal temperaments that fixes the semitone to any proper fraction of a whole tone, while keeping the notes in the right order (meaning that, for example, C, D, E, F, and F♯ are in ascending order if they preserve their usual relationships to C). That is, fixing q to a proper fraction in the relationship q t = s also defines a unique family of one equal temperament and its multiples that fulfil this relationship.

For example, where k is an integer, 12k EDO sets q = 1/2, 19 k EDO sets q = 1/3, and 31 k EDO sets q = 2 / 5 . The smallest multiples in these families (e.g. 12, 19 and 31 above) has the additional property of having no notes outside the circle of fifths. (This is not true in general; in 24 EDO, the half-sharps and half-flats are not in the circle of fifths generated starting from C.) The extreme cases are 5 k EDO, where q = 0 and the semitone becomes a unison, and 7 k EDO , where q = 1 and the semitone and tone are the same interval.

Once one knows how many steps a semitone and a tone are in this equal temperament, one can find the number of steps it has in the octave. An equal temperament with the above properties (including having no notes outside the circle of fifths) divides the octave into 7 t − 2 s steps and the perfect fifth into 4 t − s steps. If there are notes outside the circle of fifths, one must then multiply these results by n, the number of nonoverlapping circles of fifths required to generate all the notes (e.g., two in 24 EDO, six in 72 EDO). (One must take the small semitone for this purpose: 19 EDO has two semitones, one being 1 / 3 tone and the other being 2 / 3 . Similarly, 31 EDO has two semitones, one being 2 / 5 tone and the other being 3 / 5 ).

The smallest of these families is 12 k EDO, and in particular, 12 EDO is the smallest equal temperament with the above properties. Additionally, it makes the semitone exactly half a whole tone, the simplest possible relationship. These are some of the reasons 12 EDO has become the most commonly used equal temperament. (Another reason is that 12 EDO is the smallest equal temperament to closely approximate 5 limit harmony, the next-smallest being 19 EDO.)

Each choice of fraction q for the relationship results in exactly one equal temperament family, but the converse is not true: 47 EDO has two different semitones, where one is 1 / 7 tone and the other is 8 / 9 , which are not complements of each other like in 19 EDO ( 1 / 3 and 2 / 3 ). Taking each semitone results in a different choice of perfect fifth.

Related tuning systems

[edit]Equal temperament systems can be thought of in terms of the spacing of three intervals found in just intonation, most of whose chords are harmonically perfectly in tune—a good property not quite achieved between almost all pitches in almost all equal temperaments. Most just chords sound amazingly consonant, and most equal-tempered chords sound at least slightly dissonant. In C major those three intervals are:[38]

- the greater tone T = 9 / 8 = the interval from C:D, F:G, and A:B;

- the lesser tone t = 10 / 9 = the interval from D:E and G:A;

- the diatonic semitone s = 16 / 15 = the interval from E:F and B:C.

Analyzing an equal temperament in terms of how it modifies or adapts these three intervals provides a quick way to evaluate how consonant various chords can possibly be in that temperament, based on how distorted these intervals are.[38][f]

Regular diatonic tunings

[edit]

The diatonic tuning in 12 tone equal temperament (12 TET) can be generalized to any regular diatonic tuning dividing the octave as a sequence of steps T t s T t T s (or some circular shift or "rotation" of it). To be called a regular diatonic tuning, each of the two semitones ( s ) must be smaller than either of the tones (greater tone, T , and lesser tone, t ). The comma κ is implicit as the size ratio between the greater and lesser tones: Expressed as frequencies κ = T / t , or as cents κ = T − t .

The notes in a regular diatonic tuning are connected in a "spiral of fifths" that does not close (unlike the circle of fifths in 12 TET). Starting on the subdominant F (in the key of C) there are three perfect fifths in a row—F–C, C–G, and G–D—each a composite of some permutation of the smaller intervals T T t s . The three in-tune fifths are interrupted by the grave fifth D–A = T t t s (grave means "flat by a comma"), followed by another perfect fifth, E–B, and another grave fifth, B–F♯, and then restarting in the sharps with F♯–C♯; the same pattern repeats through the sharp notes, then the double-sharps, and so on, indefinitely. But each octave of all-natural or all-sharp or all-double-sharp notes flattens by two commas with every transition from naturals to sharps, or single sharps to double sharps, etc. The pattern is also reverse-symmetric in the flats: Descending by fourths the pattern reciprocally sharpens notes by two commas with every transition from natural notes to flattened notes, or flats to double flats, etc. If left unmodified, the two grave fifths in each block of all-natural notes, or all-sharps, or all-flat notes, are "wolf" intervals: Each of the grave fifths out of tune by a diatonic comma.

Since the comma, κ, expands the lesser tone t = s c , into the greater tone, T = s c κ , a just octave T t s T t T s can be broken up into a sequence s c κ s c s s c κ s c s c κ s , (or a circular shift of it) of 7 diatonic semitones s, 5 chromatic semitones c, and 3 commas κ . Various equal temperaments alter the interval sizes, usually breaking apart the three commas and then redistributing their parts into the seven diatonic semitones s, or into the five chromatic semitones c, or into both s and c, with some fixed proportion for each type of semitone.

The sequence of intervals s, c, and κ can be repeatedly appended to itself into a greater spiral of 12 fifths, and made to connect at its far ends by slight adjustments to the size of one or several of the intervals, or left unmodified with occasional less-than-perfect fifths, flat by a comma.

Morphing diatonic tunings into EDO

[edit]Various equal temperaments can be understood and analyzed as having made adjustments to the sizes of and subdividing the three intervals— T , t , and s , or at finer resolution, their constituents s , c , and κ . An equal temperament can be created by making the sizes of the major and minor tones (T, t) the same (say, by setting κ = 0, with the others expanded to still fill out the octave), and both semitones (s and c) the same, then 12 equal semitones, two per tone, result. In 12 TET, the semitone, s, is exactly half the size of the same-size whole tones T = t.

Some of the intermediate sizes of tones and semitones can also be generated in equal temperament systems, by modifying the sizes of the comma and semitones. One obtains 7 TET in the limit as the size of c and κ tend to zero, with the octave kept fixed, and 5 TET in the limit as s and κ tend to zero; 12 TET is of course, the case s = c and κ = 0 . For instance:

- 5 TET and 7 TET

- There are two extreme cases that bracket this framework: When s and κ reduce to zero with the octave size kept fixed, the result is t t t t t , a 5 tone equal temperament. As the s gets larger (and absorbs the space formerly used for the comma κ), eventually the steps are all the same size, t t t t t t t , and the result is seven-tone equal temperament. These two extremes are not included as "regular" diatonic tunings.

- 19 TET

- If the diatonic semitone is set double the size of the chromatic semitone, i.e. s = 2 c (in cents) and κ = 0 , the result is 19 TET, with one step for the chromatic semitone c, two steps for the diatonic semitone s, three steps for the tones T = t, and the total number of steps 3 T + 2 t + 2 s = 9 + 6 + 4 = 19 steps. The imbedded 12 tone sub-system closely approximates the historically important 1 / 3 comma meantone system.

- 31 TET

- If the chromatic semitone is two-thirds the size of the diatonic semitone, i.e. c = 2 / 3 s , with κ = 0 , the result is 31 TET, with two steps for the chromatic semitone, three steps for the diatonic semitone, and five steps for the tone, where 3 T + 2 t + 2 s = 15 + 10 + 6 = 31 steps. The imbedded 12 tone sub-system closely approximates the historically important 1 / 4 comma meantone.

- 43 TET

- If the chromatic semitone is three-fourths the size of the diatonic semitone, i.e. c = 3 / 4 s , with κ = 0 , the result is 43 TET, with three steps for the chromatic semitone, four steps for the diatonic semitone, and seven steps for the tone, where 3 T + 2 t + 2 s = 21 + 14 + 8 = 43. The imbedded 12 tone sub-system closely approximates 1 / 5 comma meantone.

- 53 TET

- If the chromatic semitone is made the same size as three commas, c = 3 κ (in cents, in frequency c = κ³ ) the diatonic the same as five commas, s = 5 κ , that makes the lesser tone eight commas t = s + c = 8 κ , and the greater tone nine, T = s + c + κ = 9 κ . Hence 3 T + 2 t + 2 s = 27 κ + 16 κ + 10 κ = 53 κ for 53 steps of one comma each. The comma size / step size is κ = 1 200 / 53 ¢ exactly, or κ = 22.642 ¢ ≈ 21.506 ¢ , the syntonic comma. It is an exceedingly close approximation to 5-limit just intonation and Pythagorean tuning, and is the basis for Turkish music theory.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Sethares (2005) compares several equal temperaments in a graph with axes reversed from the axes in the first comparison of equal temperaments, and identical axes of the second.[1]

- ^ "Chu-Tsaiyu [was] the first formulator of the mathematics of 'equal temperament' anywhere in the world." — Robinson (1980), p. vii[7]

- ^ 'Hepta-equal temperament' in our folk music has always been a controversial issue.[30]

- ^ From the flute for two thousand years of the production process, and the Japanese shakuhachi remaining in the production of Sui and Tang Dynasties and the actual temperament, identification of people using the so-called 'Seven Laws' at least two thousand years of history; and decided that this law system associated with the flute law.[31]

- ^

OEIS sequences that contain divisions of the octave that provide improving approximations of just intervals:

- (sequence A060528 in the OEIS) — 3:2

- (sequence A054540 in the OEIS) — 3:2 and 4:3, 5:4 and 8:5, 6:5 and 5:3

- (sequence A060525 in the OEIS) — 3:2 and 4:3, 5:4 and 8:5

- (sequence A060526 in the OEIS) — 3:2 and 4:3, 5:4 and 8:5, 7:4 and 8:7

- (sequence A060527 in the OEIS) — 3:2 and 4:3, 5:4 and 8:5, 7:4 and 8:7, 16:11 and 11:8

- (sequence A060233 in the OEIS) — 4:3 and 3:2, 5:4 and 8:5, 6:5 and 5:3, 7:4 and 8:7, 16:11 and 11:8, 16:13 and 13:8

- (sequence A061920 in the OEIS) — 3:2 and 4:3, 5:4 and 8:5, 6:5 and 5:3, 9:8 and 16:9, 10:9 and 9:5, 16:15 and 15:8, 45:32 and 64:45

- (sequence A061921 in the OEIS) — 3:2 and 4:3, 5:4 and 8:5, 6:5 and 5:3, 9:8 and 16:9, 10:9 and 9:5, 16:15 and 15:8, 45:32 and 64:45, 27:20 and 40:27, 32:27 and 27:16, 81:64 and 128:81, 256:243 and 243:128

- (sequence A061918 in the OEIS) — 5:4 and 8:5

- (sequence A061919 in the OEIS) — 6:5 and 5:3

- (sequence A060529 in the OEIS) — 6:5 and 5:3, 7:5 and 10:7, 7:6 and 12:7

- (sequence A061416 in the OEIS) — 11:8 and 16:11

- ^ For 12 pitch systems, either for a whole 12 note scale, for or 12 note subsequences embedded inside some larger scale,[38] use this analysis as a way to program software to microtune an electronic keyboard dynamically, or 'on the fly', while a musician is playing. The object is to fine tune the notes momentarily in use, and any likely subsequent notes involving consonant chords, to always produce pitches that are harmonically in-tune, inspired by how orchestras and choruses constantly re-tune their overall pitch on long-duration chords for greater consonance than possible with strict 12 TET.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ Sethares (2005), fig. 4.6, p. 58

- ^ O'Donnell, Michael. "Perceptual Foundations of Sound". Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Helmholtz, H.; Ellis, A.J. "The History of Musical Pitch in Europe". On the Sensations of Tone. Translated by Ellis, A.J. (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover. pp. 493–511.

- ^ Varieschi, Gabriele U.; Gower, Christina M. (2010). "Intonation and compensation of fretted string instruments". American Journal of Physics. 78 (1): 47–55. arXiv:0906.0127. Bibcode:2010AmJPh..78...47V. doi:10.1119/1.3226563. S2CID 20827087.

- ^ a b Kuttner (1975), p. 163

- ^ Kuttner, Fritz A. (May 1975). "Prince Chu Tsai-Yü's life and work: A re-evaluation of his contribution to equal temperament theory". Ethnomusicology. 19 (2): 163–206. doi:10.2307/850355. JSTOR 850355.

- ^ a b Robinson, Kenneth (1980). A critical study of Chu Tsai-yü's contribution to the theory of equal temperament in Chinese music. Sinologica Coloniensia. Vol. 9. Wiesbaden, DE: Franz Steiner Verlag. p. vii.

- ^ a b Robinson, Kenneth G.; Needham, Joseph (1962–2004). "Part 1: Physics". In Needham, Joseph (ed.). Physics and Physical Technology. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 4. Cambridge, UK: University Press. p. 221.

- ^ a b Zhu, Zaiyu (1584). Yuè lǜ quán shū 樂律全書 [Complete Compendium of Music and Pitch] (in Chinese).

- ^ Kuttner (1975), p. 200

- ^ Cho, Gene J. (February 2010). "The significance of the discovery of the musical equal temperament in the cultural history". Journal of Xinghai Conservatory of Music. ISSN 1000-4270. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012.

- ^ Zhu, Zaiyu (1580). Lǜ lì róng tōng 律暦融通 [Fusion of Music and Calendar] (in Chinese).

- ^ "Quantifying ritual: Political cosmology, courtly music, and precision mathematics in seventeenth-century China". uts.cc.utexas.edu. Roger Hart Departments of History and Asian Studies, University of Texas, Austin. Archived from the original on 2012-03-05. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ^ Robinson & Needham (1962–2004), p. 220 ff

- ^ Ronan, Colin (ed.). The Shorter Science & Civilisation in China (abridgemed ed.). p. 385. — reduced version of the original Robinson & Needham (1962–2004).

- ^ Hanson, Lau. 劳汉生 《珠算与实用数学》 389页 [Abacus and Practical Mathematics]. p. 389.

- ^ Galilei, V. (1584). Il Fronimo ... Dialogo sopra l'arte del bene intavolare [The Fronimo ... Dialogue on the art of a good beginning] (in Italian). Venice, IT: Girolamo Scotto. pp. 80–89.

- ^ "Resound – corruption of music". Philresound.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ^ Gorzanis, Giacomo (1982) [c. 1525~1575]. Intabolatura di liuto [Lute tabulation] (in Italian) (reprint ed.). Geneva, CH: Minkoff.

- ^ "Spinacino 1507a: Thematic Index". Appalachian State University. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Stevin, Simon (30 June 2009) [c. 1605]. Rasch, Rudolf (ed.). Van de Spiegheling der singconst. The Diapason Press. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2012 – via diapason.xentonic.org.

- ^ Lindley, Mark. Lutes, Viols, Temperaments. ISBN 978-0-521-28883-5.

- ^ Werckmeister, Andreas (1707). Musicalische paradoxal-Discourse [Paradoxical Musical Discussion] (in German).

- ^ Partch, Harry (1979). Genesis of a Music (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-306-80106-X.

- ^ Cordier, Serge. "Le tempérament égal à quintes justes". aredem.online.fr (in French). Association pour la Recherche et le Développement de la Musique. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Surjodiningrat, Sudarjana & Susanto (1972)

- ^ Morton (1980)

- ^ Morton, David (1980). May, Elizabeth (ed.). The Music of Thailand. Musics of Many Cultures. p. 70. ISBN 0-520-04778-8.

- ^ Boiles (1969)

- ^ 有关"七平均律"新文献著作的发现 [Findings of new literatures concerning the hepta – equal temperament] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-10-27.

- ^ 七平均律"琐谈--兼及旧式均孔曲笛制作与转调 [abstract of About "Seven- equal- tuning System"] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ Skinner, Myles Leigh (2007). Toward a Quarter-Tone Syntax: Analyses of selected works by Blackwood, Haba, Ives, and Wyschnegradsky. p. 55. ISBN 9780542998478.

- ^ Sethares (2005), p. 58

- ^ Monzo, Joe (2005). "Equal-temperament". Tonalsoft Encyclopedia of Microtonal Music Theory. Joe Monzo. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "665 edo". xenoharmonic (microtonal wiki). Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ "convergents log2(3), 10". WolframAlpha. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ Carlos, Wendy. "Three Asymmetric Divisions of the Octave". wendycarlos.com. Serendip LLC. Retrieved 2016-09-01.

- ^ a b c d e Milne, A.; Sethares, W.A.; Plamondon, J. (Winter 2007). "Isomorphic controllers and dynamic tuning: Invariant fingerings across a tuning continuum". Computer Music Journal. 31 (4): 15–32. doi:10.1162/comj.2007.31.4.15. ISSN 0148-9267. Online: ISSN 1531-5169

Sources

[edit]- Boiles, J. (1969). "Terpehua though-song". Ethnomusicology. 13: 42–47.

- Cho, Gene Jinsiong (2003). The Discovery of Musical Equal Temperament in China and Europe in the Sixteenth Century. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Duffin, Ross W. (2007). How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and why you should care). New York, NY: W.W.Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39306227-4.

- Jorgensen, Owen (1991). Tuning. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-290-3.

- Sethares, William A. (2005). Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale (2nd ed.). London, UK: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 1-85233-797-4.

- Surjodiningrat, W.; Sudarjana, P.J.; Susanto, A. (1972). Tone measurements of outstanding Javanese gamelans in Jogjakarta and Surakarta. Jogjakarta, IN: Gadjah Mada University Press. As cited by "The gamelan pelog scale of Central Java as an example of a non-harmonic musical scale". telia.com. Neuroscience of Music. Archived from the original on 27 January 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

- Stewart, P.J. (2006) [January 1999]. From galaxy to galaxy: Music of the spheres (Report). 8096295 – via academia.edu. "Alt. link 1". 269108386 – via researchgate.net. "Alt. link 2" – via Google docs.

- Khramov, Mykhaylo (26–29 July 2008). Approximation of 5-limit just intonation. Computer MIDI Modeling in Negative Systems of Equal Divisions of the Octave. The International Conference SIGMAP-2008. Porto. pp. 181–184. ISBN 978-989-8111-60-9. [permanent dead link]

Further reading

[edit]- Helmholtz, H. (2005) [1877 (4th German ed.), 1885 (2nd English ed.)]. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. Translated by Ellis, A.J. (reprint ed.). Whitefish, MT: Kellinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-41917893-1. OCLC 71425252 – via Internet Archive (archive.org).

— A foundational work on acoustics and the perception of sound. Especially the material in Appendix XX: Additions by the translator, pages 430–556, (pdf pages 451–577) (see also wiki article On Sensations of Tone)

External links

[edit]- An Introduction to Historical Tunings by Kyle Gann

- Xenharmonic wiki on EDOs vs. Equal Temperaments

- Huygens-Fokker Foundation Centre for Microtonal Music

- A.Orlandini: Music Acoustics

- "Temperament" from A supplement to Mr. Chambers's cyclopædia (1753)

- Barbieri, Patrizio. Enharmonic instruments and music, 1470–1900. (2008) Latina, Il Levante Libreria Editrice

- Fractal Microtonal Music, Jim Kukula.

- All existing 18th century quotes on J.S. Bach and temperament

- Dominic Eckersley: "Rosetta Revisited: Bach's Very Ordinary Temperament"

- Well Temperaments, based on the Werckmeister Definition

- FAVORED CARDINALITIES OF SCALES by PETER BUCH

Equal temperament

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Core Principles

Equal temperament is a musical tuning system that divides the octave—a frequency ratio of 2:1—into a number n of equal semitones, ensuring that each successive interval spans the same logarithmic distance in pitch.[4] This approach creates consistent interval sizes across the entire scale, allowing notes to be transposed seamlessly without altering their relative proportions.[5] In practice, the most common form is twelve-tone equal temperament (12-TET), where the octave is split into 12 equal parts, each corresponding to a semitone in the chromatic scale used in Western music.[6] The core principles of equal temperament rely on logarithmic scaling of frequencies, where each equal step multiplies the previous frequency by a constant ratio of . For 12-TET, this yields a semitone ratio of approximately 1.05946, distributing the octave's total logarithmic span evenly.[7] This logarithmic equality promotes modulation between keys without the need for retuning instruments, as the relative intervals remain identical regardless of the starting pitch.[8] The term "tempered" reflects the deliberate compromise of pure harmonic ratios—such as those in just intonation, which prioritize simple integer frequency ratios for consonant intervals like the perfect fifth (3:2)—in favor of practical uniformity, introducing slight dissonance to achieve versatility.[9] Key advantages include enabling free transposition across all keys on fixed-pitch instruments like keyboards and fretted guitars, which simplifies design and performance in ensemble settings.[4] Unlike unequal systems such as meantone temperament, which favor certain keys with purer thirds but limit modulation due to accumulating errors in remote keys, equal temperament emerged as a solution to these limitations by balancing consonance across the scale.[10] This uniformity has made 12-TET the standard for modern Western music, supporting complex harmonic progressions and chromaticism without instrumental adjustments.[2]Mathematical Basis for Equal Division

The mathematical foundation of equal temperament rests on the logarithmic perception of pitch in human hearing, where musical intervals are perceived proportionally to the logarithm of their frequency ratios rather than linear frequency differences. This perceptual model aligns with the observation that doubling a frequency (a ratio of 2:1) corresponds to an octave, the fundamental repeating unit in most musical scales, and is equivalent to a logarithmic increment of in pitch space.[11][12] To create an equal temperament, this octave interval of 1 is divided equally into parts, each of size in logarithmic units, ensuring that all steps are perceptually uniform.[13] In an -tone equal temperament system, the frequency ratio for the -th interval (spanning steps) is given by , meaning each successive note's frequency is multiplied by the generator . This geometric progression ensures transposition invariance, as scaling the entire scale by any step size yields the same relative structure. Deriving from the reference frequency (such as A4 at 440 Hz), the frequency of the -th note is , where is the number of steps from the reference. For instance, in a 12-tone system (), the semitone ratio is , so the frequency seven semitones above (a perfect fifth approximation) is .[13][14] A key property of equal temperament is its approximation of the circle of fifths, where seven steps () closely mimic the just fifth ratio of , via , or equivalently . This rational approximation, such as for , distributes the Pythagorean comma evenly, enabling smooth modulation across keys. Certain equal temperaments provide close approximations to the just perfect fifth of . In 12-TET, it is (700 cents), deviating by about -2 cents from (701.96 cents), a practical approximation with minimal beats in most musical contexts. In 53-TET, the deviation is approximately -0.07 cents, nearly exact and inaudible.[15][13][16] To quantify intervals objectively, equal temperament uses cents, a unit where one octave equals 1200 cents, derived from the formula , with as the frequency ratio. Thus, each step in an -tone system spans cents. For example, in a 5-tone system (), the basic interval is (about 240 cents), yielding a pentatonic-like scale; in a 7-tone system (), it is (about 171.43 cents), approximating diatonic steps; and in 12-tone (), it is 100 cents per semitone, as standard. These examples illustrate how the framework scales generally, prioritizing perceptual equality over just intonation purity.[17][18]Twelve-Tone Equal Temperament

Historical Origins

The concept of equal temperament, particularly the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-TET), has roots in ancient Chinese music theory, where early approximations emerged centuries before precise formulations. During the Han dynasty, mathematician and music theorist Jing Fang (78–37 BCE) developed a 60-lü (tone) system by extending the traditional 12-lü scale, creating intervals that closely approximated equal semitones through successive generations of perfect fifths, though not exactly equal.[19] This system represented an early recognition of the Pythagorean comma's implications for cyclic tuning, influencing later Chinese pitch standards. By the Southern and Northern Dynasties period, mathematician He Chengtian (370–447 CE) provided one of the first numerical approximations to 12-TET using monochord divisions, calculating semitone ratios that deviated minimally from the ideal twelfth root of two.[20] The definitive mathematical calculation of 12-TET originated in Ming dynasty China with Prince Zhu Zaiyu, who in 1584 published the exact value of the semitone as the twelfth root of two (approximately 1.059463) in his treatise Lü Lü Xin Shu, derived through iterative approximations without logarithms.[21] Zhu's work resolved longstanding inconsistencies in Chinese tuning systems, such as the cycle of fifths' failure to close perfectly, and he constructed bamboo pipes to demonstrate the scale's practicality for court music.[22] Although Zhu's innovation remained largely theoretical in China and was not widely adopted due to cultural preferences for just intonation in pentatonic scales, it predated European developments by decades. In Europe, awareness of equal temperament grew in the late 16th century amid experiments with fretted instruments and monochords. Italian lutenist Vincenzo Galilei, in his 1581 Dialogo della musica antica et moderna, described practical tuning experiments that approximated equal semitones using a 18:17 string length ratio for lutes, prioritizing playability over pure intervals.[20] Dutch mathematician Simon Stevin followed in 1585 with Van de Spiegheling der singconst, introducing logarithmic principles to advocate for equal division of the octave into 12 parts, framing it as a rational solution for polyphonic music across all keys.[23] French scholar Marin Mersenne expanded on these ideas in his 1636 Harmonie universelle, explicitly describing 12-TET with beat-based verification (e.g., fifths beating uniformly) and proposing its use for organs and harpsichords to enable modulation without retuning.[20] The 17th and 18th centuries saw increasing advocacy for equal temperament as a practical alternative to meantone tunings, which favored pure major thirds but limited key changes. German organist Andreas Werckmeister championed it in his 1687 Musicalische Temperatur, promoting "well-tempered" systems that approached equality to allow full chromatic exploration on keyboards, influencing the transition from fixed meantone organs to more flexible harpsichords.[23] Georg Andreas Sorge furthered this in his 1745–1748 treatises, including Vorgemach der musicalischen Composition, by mathematically dividing the syntonic comma to justify equal temperament for composition in remote keys.[20] Johann Sebastian Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier (1722) demonstrated the system's viability through preludes and fugues in all 24 keys, accelerating its adoption despite not specifying strict equality—tunings of the era were often close approximations. By the mid-18th century, equal temperament spread across European orchestras and ensembles, enabling seamless transposition in symphonic works by composers like Haydn and Mozart, though purists such as François Couperin resisted, favoring meantone for its sweeter consonants.[24] Jean-Philippe Rameau endorsed it from 1737 onward in Génération harmonique, arguing for equal division to support harmonic progressions in opera and ballet, overcoming earlier critiques from just intonation advocates.[25] Resistance persisted among some French theorists, but the system's versatility prevailed. In the 19th century, the rise of the modern piano cemented 12-TET as the global standard, with manufacturers like Érard and Steinway standardizing equal temperament by the 1840s to accommodate expansive repertoires from Beethoven to Chopin, where frequent modulations demanded consistent intonation across the full range.[26] This shift marked the decline of irregular temperaments in concert halls. The 20th century reinforced its dominance through electronic instruments and synthesizers, such as Robert Moog's designs in the 1960s, which inherently implemented 12-TET via voltage-controlled oscillators, embedding it in popular and experimental music genres worldwide.[27]Key Applications and Adoption

Twelve-tone equal temperament (12-TET) became the preferred tuning system for fixed-pitch instruments such as the piano, guitar, and synthesizer due to its ability to facilitate performance in all keys without retuning. On the piano, which features seven octaves with strings tuned to equal semitones, 12-TET ensures consistent intonation across the keyboard, making it ideal for solo and ensemble playing.[28] Guitars employ 12-TET through precise fret placement, allowing seamless chord progressions and transpositions, while synthesizers default to this system for electronic production, enabling standardized pitch generation in diverse musical contexts.[28] This uniformity supports polyphonic music by distributing tuning discrepancies evenly, avoiding the harsh dissonances found in unequal systems.[2] The adoption of 12-TET profoundly influenced composition by enabling extensive modulation and chromatic exploration. Johann Sebastian Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier (1722 and 1742), comprising 48 preludes and fugues in all major and minor keys, demonstrated the system's versatility, promoting its use in keyboard music despite Bach likely employing a well temperament close to equal.[2] In the Romantic era, 12-TET facilitated chromaticism and key shifts, as seen in Ludwig van Beethoven's works like his String Quartet in C-sharp minor, Op. 131, where fluid transitions between distant keys enhanced emotional expressivity without intonation issues.[28] This freedom allowed composers to exploit all 12 tones equally, expanding harmonic possibilities beyond classical constraints.[29] Today, 12-TET serves as the foundation for Western classical, jazz, and popular music, underpinning ensemble compatibility and recorded formats. It was formalized as the international standard with A4 at 440 Hz through ISO 16, first recommended in 1939 by an international conference and officially adopted in 1955, with reaffirmation in 1975, to ensure global consistency in instrument manufacturing and performance.[30] By the mid-19th century, its practicality had cemented dominance in Western culture, shifting tuning from artisanal practice to scientific precision.[31] The global influence of 12-TET stems from Western colonialism and media dissemination, which imposed European musical norms on colonized regions and beyond. During the 19th and 20th centuries, missionary activities and trade routes spread keyboard instruments tuned to 12-TET, often portraying it as aesthetically superior in colonial education and media, marginalizing indigenous scales.[32] Modern global media, including film scores and streaming platforms, further entrenches this system, though adaptations in non-Western contexts—such as microtonal adjustments in Indian or Arabic music—highlight ongoing challenges to full assimilation.[33] Despite its advantages, 12-TET introduces tempered intervals that deviate from just intonation, resulting in slightly impure thirds and sixths that can introduce subtle dissonance in dense harmonies. However, by evenly distributing the Pythagorean comma across all semitones, it eliminates the problematic "wolf" intervals of earlier systems like meantone, mitigating usability issues in polyphonic and modulating music.[31] This equality ensures practical reliability across instruments and keys, outweighing the compromises for most applications.[2]Detailed Calculations and Comparisons

In twelve-tone equal temperament (12-TET), absolute frequencies are calculated relative to the standard concert pitch of A4 at 440 Hz, using the formula , where is the number of semitones above or below A4 (positive for ascending, negative for descending).[34] This geometric progression ensures each semitone multiplies the previous frequency by the constant twelfth root of 2, approximately 1.059463, dividing the octave logarithmically into 12 equal parts of 100 cents each.[34] For example, middle C (C4), which is 9 semitones below A4 (), has a frequency of approximately 261.63 Hz. The following table lists standard frequencies for the notes in the fourth octave (from C4 to B4), computed using the A4=440 Hz reference:| Note | Semitones from A4 () | Frequency (Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| C4 | -9 | 261.63 |

| C♯4/D♭4 | -8 | 277.18 |

| D4 | -7 | 293.66 |

| D♯4/E♭4 | -6 | 311.13 |

| E4 | -5 | 329.63 |

| F4 | -4 | 349.23 |

| F♯4/G♭4 | -3 | 369.99 |

| G4 | -2 | 392.00 |

| G♯4/A♭4 | -1 | 415.30 |

| A4 | 0 | 440.00 |

| A♯4/B♭4 | 1 | 466.16 |

| B4 | 2 | 493.88 |

| Interval | Just Ratio | Just Cents | ET Cents | Deviation (ET - Just) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect Fifth | 3:2 | 701.955 | 700 | -1.955 cents |

| Major Third | 5:4 | 386.314 | 400 | +13.686 cents |

| Minor Third | 6:5 | 315.641 | 300 | -15.641 cents |

| Perfect Fourth | 4:3 | 498.045 | 500 | +1.955 cents |

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f276a910a28604e3b8afd8ba62a4678a37193480)

![{\displaystyle \ r={\sqrt[{n}]{p\ }}\ }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d528638ae9f67854ba783208c8994ba43a4ae65a)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{24}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/edf77c2ed37bcf5bd90e3a4558ab4a7971ca8c35)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2\ }}=2^{\tfrac {1}{12}}\approx 1.059463}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2263b09977831de2383c97524018d20ec330658e)

![{\displaystyle \ P_{n}=P_{a}\ \cdot \ {\Bigl (}\ {\sqrt[{12}]{2\ }}\ {\Bigr )}^{n-a}\ }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/487fc672109e43b63bee107f86de396ffc75f625)

![{\displaystyle P_{40}=440\ {\text{Hz}}\ \cdot \ {\Bigl (}{\sqrt[{12}]{2}}\ {\Bigr )}^{(40-49)}\approx 261.626\ {\text{Hz}}\ }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1af334ac01799a0d32b71259722b201a387cfe54)

![{\displaystyle P_{46}=440\ {\text{Hz}}\ \cdot \ {\Bigl (}{\sqrt[{12}]{2}}\ {\Bigr )}^{(46-49)}\approx 369.994\ {\text{Hz}}\ }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1188a55df931a93ebdc58d3d2c3a0d3762ee488c)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc835f27425fb3140e1f75a5faa35b1e8b9efc35)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{6}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2fd2e90711da1208f1bf08c8992ab44739cb9c57)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{4}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9aa163183b2c3828db27e22253d454a643a4c936)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9ca071ab504481c2bb76081aacb03f5519930710)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{32}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9744b1d14b93f31471a1ad0e7176cbd2e42f1a9)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{128}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7fe1257282e06f592d5b60e9ce503586594b865c)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{4}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5eb5da5142ec773ea1ba79813278a00c8d9ee202)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{4}]{8}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/675096532680297bc0b8e3ef793ed8b9271f628e)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{6}]{32}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e75f5ed7285d717db47b68736ff2e37df9f71737)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{12}]{2048}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/744decb84a19d221e7ce8df0ec3d315384fdd5ef)

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{7}]{3/2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7454aa10a24b520407313724534f56bb1afd7d3e)

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{13}]{3}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7e5ec1fc6cdcfa76f67e0ba6c4ea0ef97ef8960c)

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{9}]{\frac {3}{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/205558a0029464aed10a2df921ae62fe5dce2b54)

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{11}]{\frac {3}{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1a2bd388c4b859f8eec8ef51e3ec735e0c573b28)

![{\textstyle {\sqrt[{20}]{\frac {3}{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/210919b51cd0f0b620254d19f49819ddb99f5a36)