Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

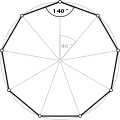

Regular polygon

View on Wikipedia| Edges and vertices | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schläfli symbol | |||||||||||||

| Coxeter–Dynkin diagram | |||||||||||||

| Symmetry group | Dn, order 2n | ||||||||||||

| Dual polygon | Self-dual | ||||||||||||

| Area (with side length ) | |||||||||||||

| Internal angle | |||||||||||||

| Internal angle sum | |||||||||||||

| Inscribed circle diameter | |||||||||||||

| Circumscribed circle diameter | |||||||||||||

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal | ||||||||||||

In Euclidean geometry, a regular polygon is a polygon that is direct equiangular (all angles are equal in measure) and equilateral (all sides have the same length). Regular polygons may be either convex or star. In the limit, a sequence of regular polygons with an increasing number of sides approximates a circle, if the perimeter or area is fixed, or a regular apeirogon (effectively a straight line), if the edge length is fixed.

General properties

[edit]

These properties apply to all regular polygons, whether convex or star:

- A regular n-sided polygon has rotational symmetry of order n.

- All vertices of a regular polygon lie on a common circle (the circumscribed circle); i.e., they are concyclic points. That is, a regular polygon is a cyclic polygon.

- Together with the property of equal-length sides, this implies that every regular polygon also has an inscribed circle or incircle that is tangent to every side at the midpoint. Thus a regular polygon is a tangential polygon.

- A regular n-sided polygon can be constructed with compass and straightedge if and only if the odd prime factors of n are distinct Fermat primes.

- A regular n-sided polygon can be constructed with origami if and only if for some , where each distinct is a Pierpont prime.[1]

Symmetry

[edit]The symmetry group of an n-sided regular polygon is the dihedral group Dn (of order 2n): D2, D3, D4, ... It consists of the rotations in Cn, together with reflection symmetry in n axes that pass through the center. If n is even then half of these axes pass through two opposite vertices, and the other half through the midpoint of opposite sides. If n is odd then all axes pass through a vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side.

Regular convex polygons

[edit]All regular simple polygons (a simple polygon is one that does not intersect itself anywhere) are convex. Those having the same number of sides are also similar.

An n-sided convex regular polygon is denoted by its Schläfli symbol . For , we have two degenerate cases:

- Monogon {1}; point

- Degenerate in ordinary space. (Most authorities do not regard the monogon as a true polygon, partly because of this, and also because the formulae below do not work, and its structure is not that of any abstract polygon.)

- Digon {2}; line segment

- Degenerate in ordinary space. (Some authorities[weasel words] do not regard the digon as a true polygon because of this.)

In certain contexts all the polygons considered will be regular. In such circumstances it is customary to drop the prefix regular. For instance, all the faces of uniform polyhedra must be regular and the faces will be described simply as triangle, square, pentagon, etc.

Angles

[edit]For a regular convex n-gon, each interior angle has a measure of:

- degrees;

- radians; or

- full turns,

and each exterior angle (i.e., supplementary to the interior angle) has a measure of degrees, with the sum of the exterior angles equal to 360 degrees or 2π radians or one full turn.

As n approaches infinity, the internal angle approaches 180 degrees. For a regular polygon with 10,000 sides (a myriagon) the internal angle is 179.964°. As the number of sides increases, the internal angle can come very close to 180°, and the shape of the polygon approaches that of a circle. However the polygon can never become a circle. The value of the internal angle can never become exactly equal to 180°, as the circumference would effectively become a straight line (see apeirogon). For this reason, a circle is not a polygon with an infinite number of sides.

Diagonals

[edit]For , the number of diagonals is ; i.e., 0, 2, 5, 9, ..., for a triangle, square, pentagon, hexagon, ... . The diagonals divide the polygon into 1, 4, 11, 24, ... pieces.[a]

For a regular n-gon inscribed in a circle of radius , the product of the distances from a given vertex to all other vertices (including adjacent vertices and vertices connected by a diagonal) equals n.

Points in the plane

[edit]For a regular simple n-gon with circumradius R and distances di from an arbitrary point in the plane to the vertices, we have[2]

For higher powers of distances from an arbitrary point in the plane to the vertices of a regular n-gon, if

- ,

then[3]

- ,

and

- ,

where m is a positive integer less than n.

If L is the distance from an arbitrary point in the plane to the centroid of a regular n-gon with circumradius R, then[3]

- ,

where .

Interior points

[edit]For a regular n-gon, the sum of the perpendicular distances from any interior point to the n sides is n times the apothem[4]: p. 72 (the apothem being the distance from the center to any side). This is a generalization of Viviani's theorem for the n = 3 case.[5][6]

Circumradius

[edit]

The circumradius R from the center of a regular polygon to one of the vertices is related to the side length s or to the apothem a by

For constructible polygons, algebraic expressions for these relationships exist .

The sum of the perpendiculars from a regular n-gon's vertices to any line tangent to the circumcircle equals n times the circumradius.[4]: p. 73

The sum of the squared distances from the vertices of a regular n-gon to any point on its circumcircle equals 2nR2 where R is the circumradius.[4]: p. 73

The sum of the squared distances from the midpoints of the sides of a regular n-gon to any point on the circumcircle is 2nR2 − 1/4ns2, where s is the side length and R is the circumradius.[4]: p. 73

If are the distances from the vertices of a regular -gon to any point on its circumcircle, then [3]

- .

Dissections

[edit]Coxeter states that every zonogon (a 2m-gon whose opposite sides are parallel and of equal length) can be dissected into or 1/2m(m − 1) parallelograms. These tilings are contained as subsets of vertices, edges and faces in orthogonal projections m-cubes.[7]

In particular, this is true for any regular polygon with an even number of sides, in which case the parallelograms are all rhombi. Regular polygons with 4m+2 sides can be dissected in a way with (2m+1)-fold radial symmetry. The list OEIS: A006245 gives the number of solutions for smaller polygons.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Sides | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 |

| Rhombs | 3 | 6 | 10 | 15 | 21 | 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Sides | 18 | 20 | 24 | 30 | 40 | 50 |

| Rhombs | 36 | 45 | 66 | 105 | 190 | 300 |

Area

[edit]The area A of a convex regular n-sided polygon having side s, circumradius R, apothem a, and perimeter p is given by[8][9]

For regular polygons with side s = 1, circumradius R = 1, or apothem a = 1, this produces the following table:[b] (Since as , the area when tends to as grows large.)

Number

of sides |

Area when side s = 1 | Area when circumradius R = 1 | Area when apothem a = 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exact | Approximation | Exact | Approximation | Relative to circumcircle area | Exact | Approximation | Relative to incircle area | |

| n | ||||||||

| 3 | | 0.433012702 | | 1.299038105 | 0.4134966714 | | 5.196152424 | 1.653986686 |

| 4 | 1 | 1.000000000 | 2 | 2.000000000 | 0.6366197722 | 4 | 4.000000000 | 1.273239544 |

| 5 | | 1.720477401 | | 2.377641291 | 0.7568267288 | | 3.632712640 | 1.156328347 |

| 6 | | 2.598076211 | | 2.598076211 | 0.8269933428 | | 3.464101616 | 1.102657791 |

| 7 | 3.633912444 | 2.736410189 | 0.8710264157 | 3.371022333 | 1.073029735 | |||

| 8 | | 4.828427125 | | 2.828427125 | 0.9003163160 | | 3.313708500 | 1.054786175 |

| 9 | 6.181824194 | 2.892544244 | 0.9207254290 | 3.275732109 | 1.042697914 | |||

| 10 | | 7.694208843 | | 2.938926262 | 0.9354892840 | | 3.249196963 | 1.034251515 |

| 11 | 9.365639907 | 2.973524496 | 0.9465022440 | 3.229891423 | 1.028106371 | |||

| 12 | | 11.19615242 | 3 | 3.000000000 | 0.9549296586 | | 3.215390309 | 1.023490523 |

| 13 | 13.18576833 | 3.020700617 | 0.9615188694 | 3.204212220 | 1.019932427 | |||

| 14 | 15.33450194 | 3.037186175 | 0.9667663859 | 3.195408642 | 1.017130161 | |||

| 15 | | 17.64236291 | | 3.050524822 | 0.9710122088 | | 3.188348426 | 1.014882824 |

| 16 | | 20.10935797 | | 3.061467460 | 0.9744953584 | | 3.182597878 | 1.013052368 |

| 17 | 22.73549190 | 3.070554163 | 0.9773877456 | 3.177850752 | 1.011541311 | |||

| 18 | 25.52076819 | 3.078181290 | 0.9798155361 | 3.173885653 | 1.010279181 | |||

| 19 | 28.46518943 | 3.084644958 | 0.9818729854 | 3.170539238 | 1.009213984 | |||

| 20 | | 31.56875757 | | 3.090169944 | 0.9836316430 | | 3.167688806 | 1.008306663 |

| 100 | 795.5128988 | 3.139525977 | 0.9993421565 | 3.142626605 | 1.000329117 | |||

| 1000 | 79577.20975 | 3.141571983 | 0.9999934200 | 3.141602989 | 1.000003290 | |||

| 104 | 7957746.893 | 3.141592448 | 0.9999999345 | 3.141592757 | 1.000000033 | |||

| 106 | 79577471545 | 3.141592654 | 1.000000000 | 3.141592654 | 1.000000000 | |||

Of all n-gons with a given perimeter, the one with the largest area is regular.[10]

Constructible polygon

[edit]Some regular polygons are easy to construct with compass and straightedge; other regular polygons are not constructible at all. The ancient Greek mathematicians knew how to construct a regular polygon with 3, 4, or 5 sides,[11]: p. xi and they knew how to construct a regular polygon with double the number of sides of a given regular polygon.[11]: pp. 49–50 This led to the question being posed: is it possible to construct all regular n-gons with compass and straightedge? If not, which n-gons are constructible and which are not?

Carl Friedrich Gauss proved the constructibility of the regular 17-gon in 1796. Five years later, he developed the theory of Gaussian periods in his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. This theory allowed him to formulate a sufficient condition for the constructibility of regular polygons:

- A regular n-gon can be constructed with compass and straightedge if n is the product of a power of 2 and any number of distinct Fermat primes (including none).

(A Fermat prime is a prime number of the form ) Gauss stated without proof that this condition was also necessary, but never published his proof. A full proof of necessity was given by Pierre Wantzel in 1837. The result is known as the Gauss–Wantzel theorem.

Equivalently, a regular n-gon is constructible if and only if the cosine of its common angle is a constructible number—that is, can be written in terms of the four basic arithmetic operations and the extraction of square roots.

Regular skew polygons

[edit] The cube contains a skew regular hexagon, seen as 6 red edges zig-zagging between two planes perpendicular to the cube's diagonal axis. |

The zig-zagging side edges of a n-antiprism represent a regular skew 2n-gon, as shown in this 17-gonal antiprism. |

A regular skew polygon in 3-space can be seen as nonplanar paths zig-zagging between two parallel planes, defined as the side-edges of a uniform antiprism. All edges and internal angles are equal.

The Platonic solids (the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron) have Petrie polygons, seen in red here, with sides 4, 6, 6, 10, and 10 respectively. |

More generally regular skew polygons can be defined in n-space. Examples include the Petrie polygons, polygonal paths of edges that divide a regular polytope into two halves, and seen as a regular polygon in orthogonal projection.

In the infinite limit regular skew polygons become skew apeirogons.

Regular star polygons

[edit]| 2 < 2q < p, gcd(p, q) = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schläfli symbol | {p/q} | |||

| Vertices and Edges | p | |||

| Density | q | |||

| Coxeter diagram | ||||

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (Dp) | |||

| Dual polygon | Self-dual | |||

| Internal angle (degrees) | [12] | |||

A non-convex regular polygon is a regular star polygon. The most common example is the pentagram, which has the same vertices as a pentagon, but connects alternating vertices.

For an n-sided star polygon, the Schläfli symbol is modified to indicate the density or "starriness" m of the polygon, as {n/m}. If m is 2, for example, then every second point is joined. If m is 3, then every third point is joined. The boundary of the polygon winds around the center m times.

The (non-degenerate) regular stars of up to 12 sides are:

- Pentagram – {5/2}

- Heptagram – {7/2} and {7/3}

- Octagram – {8/3}

- Enneagram – {9/2} and {9/4}

- Decagram – {10/3}

- Hendecagram – {11/2}, {11/3}, {11/4} and {11/5}

- Dodecagram – {12/5}

m and n must be coprime, or the figure will degenerate.

The degenerate regular stars of up to 12 sides are:

- Tetragon – {4/2}

- Hexagons – {6/2}, {6/3}

- Octagons – {8/2}, {8/4}

- Enneagon – {9/3}

- Decagons – {10/2}, {10/4}, and {10/5}

- Dodecagons – {12/2}, {12/3}, {12/4}, and {12/6}

| Grünbaum {6/2} or 2{3}[13] |

Coxeter 2{3} or {6}[2{3}]{6} |

|---|---|

|

|

| Doubly-wound hexagon | Hexagram as a compound of two triangles |

Depending on the precise derivation of the Schläfli symbol, opinions differ as to the nature of the degenerate figure. For example, {6/2} may be treated in either of two ways:

- For much of the 20th century (see for example Coxeter (1948)), we have commonly taken the /2 to indicate joining each vertex of a convex {6} to its near neighbors two steps away, to obtain the regular compound of two triangles, or hexagram. Coxeter clarifies this regular compound with a notation {kp}[k{p}]{kp} for the compound {p/k}, so the hexagram is represented as {6}[2{3}]{6}.[14] More compactly Coxeter also writes 2{n/2}, like 2{3} for a hexagram as compound as alternations of regular even-sided polygons, with italics on the leading factor to differentiate it from the coinciding interpretation.[15]

- Many modern geometers, such as Grünbaum (2003),[13] regard this as incorrect. They take the /2 to indicate moving two places around the {6} at each step, obtaining a "double-wound" triangle that has two vertices superimposed at each corner point and two edges along each line segment. Not only does this fit in better with modern theories of abstract polytopes, but it also more closely copies the way in which Poinsot (1809) created his star polygons – by taking a single length of wire and bending it at successive points through the same angle until the figure closed.

Duality of regular polygons

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

All regular polygons are self-dual to congruency, and for odd n they are self-dual to identity.

In addition, the regular star figures (compounds), being composed of regular polygons, are also self-dual.

Regular polygons as faces of polyhedra

[edit]A uniform polyhedron has regular polygons as faces, such that for every two vertices there is an isometry mapping one into the other (just as there is for a regular polygon).

A quasiregular polyhedron is a uniform polyhedron which has just two kinds of face alternating around each vertex.

A regular polyhedron is a uniform polyhedron which has just one kind of face.

The remaining (non-uniform) convex polyhedra with regular faces are known as the Johnson solids.

A polyhedron having regular triangles as faces is called a deltahedron.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ (sequence A007678 in the OEIS)

- ^ Results for R = 1 and a = 1 obtained with Maple, using function definition:

The expressions for n = 16 are obtained by twice applying the tangent half-angle formula to tan(π/4)

f := proc (n) options operator, arrow; [ [convert(1/4*n*cot(Pi/n), radical), convert(1/4*n*cot(Pi/n), float)], [convert(1/2*n*sin(2*Pi/n), radical), convert(1/2*n*sin(2*Pi/n), float), convert(1/2*n*sin(2*Pi/n)/Pi, float)], [convert(n*tan(Pi/n), radical), convert(n*tan(Pi/n), float), convert(n*tan(Pi/n)/Pi, float)] ] end proc

References

[edit]- ^ Hwa, Young Lee (2017). Origami-Constructible Numbers (PDF) (MA thesis). University of Georgia. pp. 55–59.

- ^ Park, Poo-Sung. "Regular polytope distances", Forum Geometricorum 16, 2016, 227-232. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2016volume16/FG201627.pdf Archived 2016-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Meskhishvili, Mamuka (2020). "Cyclic Averages of Regular Polygons and Platonic Solids". Communications in Mathematics and Applications. 11: 335–355. arXiv:2010.12340. doi:10.26713/cma.v11i3.1420 (inactive 1 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ a b c d Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007 (orig. 1929).

- ^ Pickover, Clifford A, The Math Book, Sterling, 2009: p. 150

- ^ Chen, Zhibo, and Liang, Tian. "The converse of Viviani's theorem", The College Mathematics Journal 37(5), 2006, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Coxeter, Mathematical recreations and Essays, Thirteenth edition, p.141

- ^ "Math Open Reference". Retrieved 4 Feb 2014.

- ^ "Mathwords".

- ^ Chakerian, G.D. "A Distorted View of Geometry." Ch. 7 in Mathematical Plums (R. Honsberger, editor). Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, 1979: 147.

- ^ a b Bold, Benjamin. Famous Problems of Geometry and How to Solve Them, Dover Publications, 1982 (orig. 1969).

- ^ Kappraff, Jay (2002). Beyond measure: a guided tour through nature, myth, and number. World Scientific. p. 258. ISBN 978-981-02-4702-7.

- ^ a b Are Your Polyhedra the Same as My Polyhedra? Branko Grünbaum (2003), Fig. 3

- ^ Regular polytopes, p.95

- ^ Coxeter, The Densities of the Regular Polytopes II, 1932, p.53

Further reading

[edit]- Lee, Hwa Young; "Origami-Constructible Numbers".

- Coxeter, H.S.M. (1948). Regular Polytopes. Methuen and Co.

- Grünbaum, B.; Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra?, Discrete and comput. geom: the Goodman-Pollack festschrift, Ed. Aronov et al., Springer (2003), pp. 461–488.

- Poinsot, L.; Memoire sur les polygones et polyèdres. J. de l'École Polytechnique 9 (1810), pp. 16–48.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Regular polygon". MathWorld.

- Regular Polygon description With interactive animation

- Incircle of a Regular Polygon With interactive animation

- Area of a Regular Polygon Three different formulae, with interactive animation

- Renaissance artists' constructions of regular polygons Archived 2006-02-12 at the Wayback Machine at Convergence Archived 2006-02-12 at the Wayback Machine